Abstract

In this paper, we investigate the effect of output quantization on the secrecy capacity of the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel. As a result, a closed-form expression with infinite summation terms of the secrecy capacity of the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is derived for the case when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs. In particular, computable tight upper and lower bounds on the secrecy capacity are obtained. Theoretically, we prove that when the legitimate receiver has unquantized outputs while the eavesdropper has binary quantized outputs, the secrecy capacity is larger than that when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs or both have binary quantized outputs. Further, numerical results show that in the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (of the main channel) region, the secrecy capacity of the binary input Gaussian wiretap channel when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs is larger than the capacity when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have binary quantized outputs; as the SNR increases, the secrecy capacity when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have binary quantized outputs tends to overtake.

1. Introduction

The capacity of the Gaussian channel with binary inputs is a particularly important metric on the performance of practical communication systems. If there exists an eavesdropper besides the legitimate users, the capacity of the Gaussian wiretap channel is usually studied from the perspective of information-theoretic secrecy. The concept of information-theoretic secrecy was first introduced by Shannon in [1], where he proposed a cipher system with perfect secrecy to ensure the confidentiality of communication. Later, Wyner introduced a wiretap channel in [2] to achieve the information-theoretic secrecy under a weak secrecy constraint (i.e., the rate of information leaked to the eavesdropper is made vanishing). In [3], Csiszár and Körner extended Wyner’s work to a general broadcast channel model with one common message and one confidential message.

In the Gaussian wiretap channel, a wiretapper eavesdrops the communication through another Gaussian channel. Recently, the Gaussian wiretap channel with constrained/finite inputs has attracted increasing research attention [4,5,6,7,8]. The closed-form expression of the secrecy capacity of the Gaussian wiretap channel with continuous input signal was given in [9]. The work in [4] considered the Gaussian wiretap channel with M-ary pulse amplitude modulation (M-PAM) inputs and established the necessary conditions for the input power allocation and the input distribution in order to maximize the achievable secrecy rate. The effects of finite-alphabet inputs on the achievable secrecy rate of the multi-antenna wiretap systems were investigated in [5,6].

In this paper, two constraints are imposed on the Gaussian wiretap channel: the input signal is binary; the output is restricted to the binary quantized output and the unquantized output. Roughly speaking, the unquantized output is the original continuous channel output signal, while the binary quantized output is obtained from the binary quantization of the original continuous channel output. In the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel (BI-GWC), since the legitimate receiver and the wiretapper can have either binary quantized outputs or unquantized outputs, there are four cases under consideration:

- Both the legitimate receiver and the wiretapper have unquantized outputs;

- Both the legitimate receiver and the wiretapper have binary quantized outputs;

- The legitimate receiver has binary quantized outputs, while the wiretapper has unquantized outputs;

- The legitimate receiver has unquantized outputs, while the wiretapper has binary quantized outputs.

So far, all the known works about BI-GWC [4,5,6] focus on Case 1, where the classical results in [2,3,9] were used to optimize the input power and the input distribution. However, no closed-form expression was derived. For the other three cases, their secrecy capacities have not yet been studied. In this paper, for Case 1, we give a close-form expression of the secrecy capacity. To reduce the computational complexity, tight upper and lower bounds on the secrecy capacity are also obtained. For Case 2, we transform the channel to a binary symmetric wiretap channel, and hence obtain its secrecy capacity. For Cases 3 and 4, we derive lower bounds on the secrecy capacity, respectively.

Moreover, it is known that the quantized output leads to a lower channel capacity than the unquantized output does for the binary input Gaussian channel [10]. However, in the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel, the problem is whether quantized output would still lead to a lower secrecy capacity. In this paper, we investigate this problem by comparing the secrecy capacities of these four cases. We theoretically prove that secrecy capacity for Case 4 is larger than those of Cases 1 and 2. Further, we observe from the numerical results that the secrecy capacity for Case 1 is larger than that for Case 2 in the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (main channel) region; however, the later tends to overtake when SNR increases. In other words, unlike the binary-input Gaussian Channel, the impact of quantization of the output signal becomes insignificant in the high SNR region for Cases 1 and 2 of binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Firstly, the system model of the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is introduced in Section 2. Next, the secrecy capacities of the four cases are studied in Section 3, and the numerical results are demonstrated in Section 4 respectively. Finally, the conclusion is given in Section 5.

2. System Model

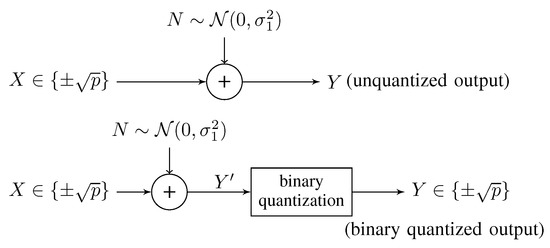

2.1. Gaussian Channel with Binary Inputs

The model of Gaussian channel with binary input is shown in Figure 1. Let be the binary input of the channel, where p is the signal power constraint. The channel output is described by

where N is a Gaussian noise with variance , and N is independent of the channel input X. Without loss of generality, we assume that N is zero-mean; i.e., . Denote the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between the input signal and noise as .

Figure 1.

The Gaussian channel with binary inputs and quantized/unquantized outputs.

In particular, we restrict to two output schemes:

- Unquantized outputs:If the channel output signal is directly processed by the receiver without binary quantization as shown in Figure 1, we call it the unquantized output. The channel output Y is a continuous signal, having the conditional probability density functionWith the unquantized output, a closed-form expression of the channel capacity for the BI-GWC was given in [11] aswhere . This channel capacity is achieved if and only if the input signal is uniformly distributed [11].For the sake of simplifying computation in what follows, the channel capacity can be approximated by keeping the first m terms of the summation as [11]

- Binary quantized outputs:Through a binary quantization, the binary quantized output iswhere is the original continuous channel output signal.In fact, this case can be modeled as the a binary symmetric channel with transition probability [10]. By means of the results for binary symmetric channel [12], we can obtain the channel capacity for the BI-GWC with binary quantized outputs aswhere is the binary entropy function. Note that is achieved iff the binary input distribution is uniform [12].

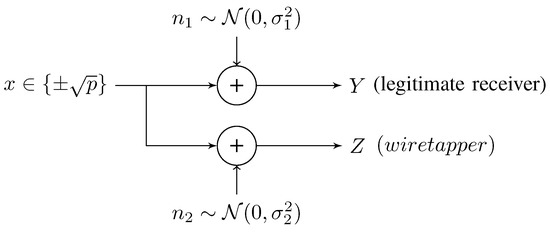

2.2. Gaussian Wiretap Channel with Binary Inputs

The binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is shown in Figure 2, where an external wiretapper eavesdrops the communication through another Gaussian channel. The channel output Y at the legitimate receiver and the channel output Z at the eavesdropper are described by

where X is the antipodal transmission signal; and are the additive Gaussian noises of the main channel and the wiretap channel, respectively. Without loss of generality, we assume that and are zero-mean, and . Then, the SNR of the legitimate channel and the wiretap channel are and , respectively. Particularly, we only consider , since a reliable and secure communication is possible only in this case [9].

Figure 2.

The binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel.

3. BI-GWC with/without Output Quantization

In this section, we study the secrecy capacities of the four cases mentioned in Section 1, which are denoted by , and , respectively. Since only if both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs or both have binary quantized outputs, the original channel is a stochastically degraded Gaussian wiretap channel (detailed explanation to follow). Then, we investigate the secrecy capacity of the four cases in two groups.

3.1. Both the Legitimate Receiver and the Eavesdropper Have Unquantized Outputs or Both Have Binary Quantized Outputs

If both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs, the difference between the channel output Y and Z is caused by the the additive Gaussian noise and . According to the assumption , the wiretap channel output Z is stochastically degraded of the main channel output Y, which means that there exists a such that , where has the same conditional marginal distribution as Z; i.e., . Hence, in this case, the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is a stochastically degraded binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel.

If the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have binary quantized outputs (as mentioned in Section 2.2), the main channel and the wiretap channel are equal to the corresponding binary symmetric channels with transition probability and , respectively. Similarly, under this assumption , this case can be modeled as a stochastically degraded binary symmetric wiretap channel.

By means of the results of a stochastically degraded wiretap channel [2,3], we can obtain the secrecy capacities for these two cases, whose proof will given in Appendix A.

Theorem 1.

If both the eavesdropper and the legitimate receiver have unquantized outputs or both have binary quantized outputs, the secrecy capacity of the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is

where is the probability distribution of the input signals; is the uniform input distribution.

Based on Theorem 1, we can derive their closed-form expressions in Section 3.1.1 and Section 3.1.2, respectively.

3.1.1. BI-GWC: Secrecy Capacity When the Legitimate Receiver and the Eavesdropper Have Unquantized Outputs

For this case, we first derive a closed-form expression for the secrecy capacity in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

When both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs, the secrecy capacity for the binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel is

where is as defined in Equation (1).

Proof.

Recall that the channel capacity of the binary-input Gaussian channel with unquantized outputs is achieved by uniform input distribution [11]. This means and . Following Theorem 1, we then have

☐

According to Theorem 2, we deduce the closed-form expression of the secrecy capacity . However, contains a summation of infinite series, and so does. In order to give a computable expression of the channel capacity, we make use of an approximation of by Equation (2); i.e.,

Specifically, we study the behaviour of and thus derive upper and lower bounds on as follows.

Property 1.

The following corollary is a direct consequence of Property 1.

Corollary 1.

can be upper and lower bounded by and respectively, as follows:

In fact, Corollary 1 provides computable lower bounds and upper bounds on with low computational complexity. Note from the Corollary 1, the series at an even/odd number m of summation terms results in a lower/upper bound on the channel capacity , which can be arbitrarily tight provided that m is sufficiently large. As an illustration, in Section 4, we show the upper and the lower bound are very tight, even for .

3.1.2. BI-GWC: Secrecy Capacity When the Legitimate Receiver and the Eavesdropper Have Binary Quantized Outputs

Note that there exists a method in [10] which can be used to transform a binary-input and binary quantized-output Gaussian channel into a binary symmetric channel. That is, under the assumption , this case can be modeled as a stochastically degraded binary symmetric channel. Based on the results of a degraded binary symmetric wiretap channel [8], we get its secrecy capacity in the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

The secrecy capacity of the Gaussian channel with binary inputs and binary quantized outputs is

where , and and are the transition probabilities of the equivalent binary symmetric channels of the main channel and the wiretap channel, respectively.

3.2. One of the Legitimate Receiver and the Eavesdropper Has Binary Quantized Outputs and the Other Has Unquantized Outputs

3.2.1. BI-GWC: Secrecy Capacity When the Legitimate Receiver Has Binary Quantized Outputs and the Eavesdropper Has Unquantized Outputs

In this case, the channel for the legitimate receiver is equal to a binary symmetric channel, whilst the channel for the eavesdropper remains a binary-input Gaussian channel. Since the channel cannot be seen as a degraded one, Theorem 1 is not suitable for this case. Then, we give a lower bound on the secrecy capacity base on the result of normal broadcast channel [3] as follows.

where ; denotes the lower bound on the secrecy capacity ; and (a) follows from the fact that the uniform input distribution achieves the channel capacity of and [11,12].

3.2.2. BI-GWC: Secrecy Capacity When the Legitimate Receiver Has Unquantized Outputs and the Eavesdropper Has Binary Quantized Outputs

In this subsection, the case is considered when the legitimate receiver has unquantized outputs, whilst the eavesdropper has binary quantized outputs. As same as the above case, a lower bound on the secrecy capacity can be given by

where denotes the lower bound on the secrecy capacity , and (a) follows from the fact that the uniform input distribution achieves the channel capacity of and [11,12].

Based on the secrecy capacities and the lower bounds on the secrecy capacity derived for the four cases above, we are able to have the following comparison.

Corollary 2.

.

Proof.

From this corollary, we see that when the legitimate receiver has unquantized outputs and the eavesdropper has binary quantized outputs, the secrecy capacity is larger than those when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have unquantized outputs or both have binary quantized outputs. This is because the unquantized output provides a higher channel capacity for the legitimate receiver while the binary quantized output leads to a lower wiretap channel capacity for the eavesdropper.

Note that when the legitimate receiver has binary quantized outputs and the eavesdropper has unquantized outputs, we give a lower bound on the secrecy capacity, and thus it is not sufficient to compare with the capacities of the other cases. In addition, it is also hard to compare and through the closed-form expression. The comparison of and will be given through numerical results in the next section.

4. Numerical Results

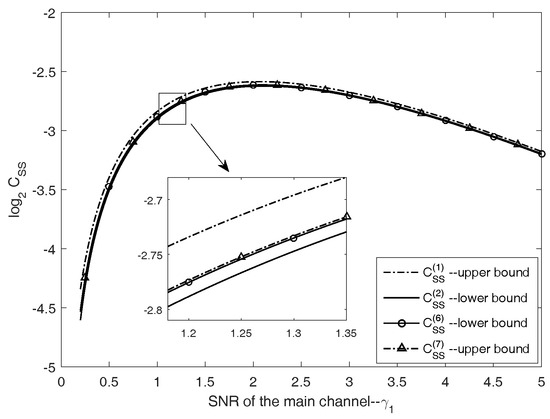

4.1. Comparison of , , and

In this subsection, we give the numerical comparison of the secrecy capacity , , , and . Recall that are the SNRs of the legitimate channel and the wiretap channel, respectively. Denote the SNR gap to be .

First, in Figure 3, we evaluate the tightness of the upper and the lower bounds on by plotting the approximation . The curves of for are plotted versus . It can be seen that the gap between the upper and the lower bounds becomes indistinguishable as m increases. Especially, when , the gap between and is already quite small. This indicates that an accurate evaluation of can be done with less computational complexity by only involving summation terms in .

Figure 3.

Lower and upper bounds on as .

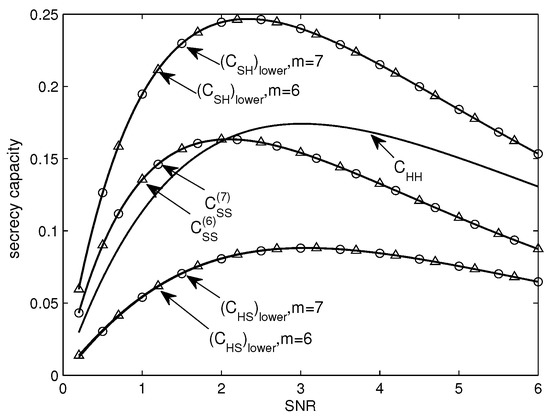

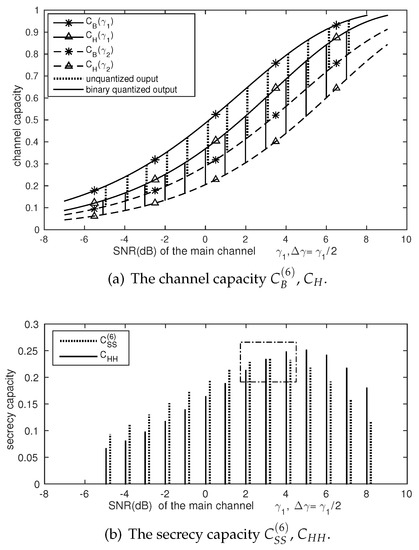

In Figure 4, we compare the , , and . and are plotted as an upper and a lower bound on , respectively. Moreover, Figure 4 also depicts the approximations on and by . All the curves are plotted with respect to with = = . From Figure 4, it is clear that —as a lower bound on —is strictly larger than both and . —as a lower bound on —is strictly smaller than both and . This confirms the result in Corollary 2. Further, we notice that there is a crossing point where , and the secrecy capacity is larger than at low SNR; whilst as SNR increases, overtakes . This gives a rough numerical comparison of and . In the following subsection, we will give more details about the comparison of and .

Figure 4.

Bounds on secrecy capacities of binary-input Gaussian wiretap channel (BI-GWC) as . SNR: signal-to-noise ratio.

4.2. Comparison from the Perspectives of SNR and SNR/bit

In this subsection, we look into the comparison of and from the perspectives of the SNR and the SNR per bit of the channel to the legitimate receiver. Following the numerical evaluations in the previous subsection, we use and to approximate and respectively.

Figure 5 consists of two sub-figures to illustrate how the crossing point occurs as . In Figure 5a, we plot the curves and , which are the capacity of the legitimate channel with unquantized outputs and with binary quantized outputs, respectively. Correspondingly, the capacity of the wiretap channel and are also plotted. In Figure 5b, the comparison of the secrecy capacities and are shown versus a series of .

Figure 5.

, , ,, .

In Figure 5a, , and increase with an increasing SNR . However, this phenomenon does not apply to the secrecy capacities and in Figure 5b. In fact, as shown in Figure 5b, both and first increase and then decrease with an increasing . In other words, unlike in the traditional communication scenario, increasing SNR does not always help to achieve a higher transmission rate when secrecy is also under consideration. The underlying cause is that is the increase from to , while is the increase from to . However, these two increases do not always result in the increase of and . The crossing point occurs when these two increases and are the same.

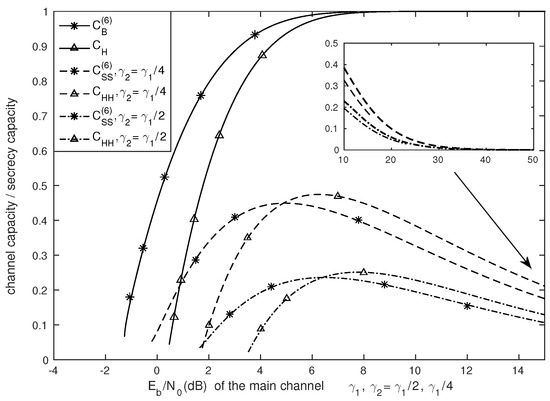

Figure 6 shows the relation between energy and the secrecy capacity. The channel capacities and , the secrecy capacities and are plotted against the SNR per bit for .

Figure 6.

, , , by SNR/bit, .

Note that SNR per bit is the energy per bit to noise power spectral density ratio (i.e., ), where is the average energy per information bit and is the variance of Gaussian noise of the main channel. Since and the SNR , SNR per bit is related to the SNR definition as follows:

Comparing with and comparing with under the same value, it can be seen how much extra SNR per bit is needed when considering secrecy. For instance, as shown in Figure 6, to approach the channel capacity , the SNR per bit is needed. While to approach the same secrecy capacity with the unquantized output (i.e., ), the SNR per bit is needed. Therefore, the secure communication comes with an additional cost of more than . A similar behavior applies to the case when both the legitimate receiver and the eavesdropper have binary quantized outputs.

Besides, as shown in Figure 6, with respect to SNR per bit, and do not increase monotonically, and this phenomenon is the same as that in Figure 4. Interestingly, as (also ), we observe that and approach to zero as shown in Figure 6. The underlying reason is that both and approach to for the high SNR region, irrespectively of unquantized or quantized outputs.

Furthermore, we denote to be the secrecy capacity and to be the corresponding SNR per bit at the crossing point (). In Figure 6, we observe that increases with respect to , while decreases with respect to . This indicates a reduction in energy cost per bit and an increase of the secrecy capacity in case of a weaker eavesdropper (which results in a larger ).

In addition, since approach to 0 as , for an admissible secrecy rate, there are two possible SNR per bit to achieve it. For the sake of energy saving, a smaller is of great interest. For instance, if the targeted secrecy rate is less than , then it is possible to achieve the secure communication with an SNR per bit smaller than .

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the secrecy capacity of the Gaussian wiretap channel under two practical constraints: (1) binary inputs; and (2) binary output quantization. Consequently, a closed-form expression for the secrecy capacity was derived when both the legitimate receiver and eavesdropper have unquantized outputs, and a tight upper and a lower bound on the secrecy capacity were obtained with less computational complexity. Besides, lower bounds were provided for other cases. Numerical results show the comparison of the secrecy capacities of the four cases, and provide insights into the energy cost for the secrecy.

Acknowledgments

This work of Chao Qi was supported in part by the Major Frontier Project of Sichuan Province under Grant 2015JY0282, the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) under Grant 2015AA01A710, and the National Science Foundation of China under Grant 61325005.

Author Contributions

A. J. Han Vinck provided the idea of the paper. Chao Qi performed the theoretical results. Chao Qi carried out the numerical simulation supervised by Yanling Chen and A. J. Han Vinck. All authors have extensively contributed to the overall discussion and preparation of the manuscript, as well as read and approved the final manuscript version.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

Proof.

For a stochastically degraded BI-GWC with input output Y at the legitimate receiver and Z at the eavesdropper, there exists a such that forms a Markov chain; and its conditional marginal distribution is the same as (thus is the same as as well). Therefore, we have

Note that is a concave function with respect to the input probability distribution , since is concave with respect to by following the proof in Lemma 1 in [13].

Let be the uniform distribution over the input signals. When both the legitimate receiver and eavesdropper have unquantized outputs or both have binary quantized outputs, the channel capacity can be achieved at That is, maximizes and simultaneously. Thus it is a stationary point of . In addition to the concavity of , we conclude that maximizes i.e.,

☐

Appendix B. Proof of Property 1

Proof.

First we prove as follows:

where (a) follows from ; (b) follows from by > 0, , and the property [11], such that .

Similarly, one can show that

Thus we have

i.e., Property 1-1.

Define By the proof of Property 1-1, we have This implies that is monotonically decreasing with respect to Since we have the following:

This establishes Property 1-2.

A similar proof applies to establish Property 1-3.

Property 1-4 follows directly by the convergence of as shown in Proposition 3 of [11].

References

- Shannon, C.E. Communication theory of secrecy systems. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1949, 28, 656–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyner, A. The wire-tap channel. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1975, 54, 1355–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, I.; Körner, J. Broadcast channels with confidential messages. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1978, 24, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.R.D.; Somekh-Baruch, A.; Bloch, M. On Gaussian wiretap channels with M-PAM inputs. In Proceedings of the 2010 European Wireless Conference, Lucca, Italy, 12–15 April 2010; pp. 774–781.

- Bashar, S.; Ding, Z.; Xiao, C. On the secrecy rate of multi-antenna wiretap channel under finite-alphabet input. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2011, 15, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashar, S.; Ding, Z.; Xiao, C. On secrecy rate analysis of MIMO wiretap channels driven by finite-alphabet input. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2012, 60, 3816–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Wong, T.F.; Shea, J.M. Secret-sharing LDPC codes for the BPSK-constrained Gaussian wiretap channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2011, 6, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, M.; Barros, J. Physical-Layer Security: From Information Theory to Security Engineering; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Leung-Yan-Cheong, S.; Hellman, M.E. The Gaussian wire-tap channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1978, 24, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proakis, J.G. Digital Communications, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nasif, A.; Karystinos, G.N. Binary transmissions over additive Gaussian noise: A closed-form expression for the channel capacity. In Proceedings of the 2005 Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS), Dayton, OH, USA, 16–18 March 2005.

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leung-Yan-Cheong, S. On a special class of wiretap channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1977, 23, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).