Do Low Income Youth of Color See “The Bigger Picture” When Discussing Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Public Health Literacy Campaign

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Participant Responses to TBP Messages

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Integration of Central Messages of PSAs from Post-Viewing Questionnaires

3.2. Prominent Public Health Themes

3.3. Underlying Sociological Themes

3.4. Differential Impact of Setting on Participant Responses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Menke, A.; Casagrande, S.; Geiss, L.; Cowie, C.C. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes among Adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA 2015, 314, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabelea, D.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Saydah, S.; Imperatore, G.; Linder, B.; Divers, J.; Hamman, R.F. Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Among Children and Adolescents From 2001 to 2009. JAMA 2014, 311, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuseppina, I.; Boyle, J.P.; Thompson, T.J.; Case, D.; Dabelea, D.; Standiford, D. Projections of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Burden in the U.S. Population Aged <20 Years Through 2050. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2515–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C.J.; Yeager, D.S.; Hinojosa, C.P.; Chabot, A.; Bergen, H.; Kawamura, M.; Steubing, F. Harnessing adolescent values to motivate healthier eating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10830–10835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Huey, N. Messengers of Truth and Health—Young Artists of Color Raise Their Voices to Prevent Diabetes. JAMA 2018, 319, 1076–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Ling, P.; Fine, S.; Boyer, C.; Rogers, E.; Vargas, RA.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Chou, W.S. Reducing Cancer and Cancer Disparities: Lessons from a Youth-Generated Diabetes Prevention Campaign. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, S103–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollust, S.E.; Lantz, P.M. Communicating population health: Print news media coverage of type 2 diabetes. Social Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.; Fine, S.; Handley, M.A.; Davis, H.; Kass, J.; Schillinger, D. Development and Early Implementation of The Bigger Picture, a Youth-Targeted Public Health Literacy Campaign to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.A.; Fine, S.C.; Handley, M.A.; Davis, H.B.; Kass, J.; Schillinger, D. Engaging Minority Youth in Diabetes Prevention Efforts Through a Participatory, Spoken-Word Social Marketing Campaign. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000, 15, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.A.; Bess, K.D.; Tucker, H.A.; Boyd, D.L.; Tuchman, A.M.; Wallston, K.A. Public Health Literacy Defined. Am. J. Prev Med. 2009, 36, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, D.; Marvasti, A. Doing Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Guide; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, K.M.; Pinkston, M.M.; Poston, W.S.C. Obesity and the built environment. J. Am. Dietetic. Assoc. 2005, 105, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, R.M. Improving Health by Improving Health Literacy. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 784–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Grumbach, K.; Piette, J.; Wang, F.; Osmond, D.; Daher, C.; Bindman, A.B. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 2002, 288, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| The Bigger Picture Campaign Spoken Word Piece and Film | Public Health Literacy Intended Public Health Message | Film Genre (and Accompanying Youth Value) | Participants Fully Understood the Film’s Public Health Message | Participants Discussed a Theme Related, But Not Central, to the Film’s Public Health Message | Participants Expressed an Unrelated Public Health Message | The Film Did Not Convey its Public Health Message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pushin’ Weight | Profit-hungry food industries target youth with addictive sugary foods. | Dark Parody (Defiance) | 3/10 Key Quote: “how from a young age sugar is shown as good and how fast it gets addictive but how bad it is for you” | 4/10 Key Quote: “Sugar consumption” | 2/10 Key Quote: “controlling your weight by watching what you eat” | 1/10 Key Quote: “A drug dealer showing everyone how to sell drugs” |

| 2. Product of His Environment | Institutionally reinforced social conditions, such as poverty, food insecurity, and violence, increase diabetes risk. | Drama (Social Justice) | 6/10 Key Quote: “a young boy, how he doesn’t have access to food let alone healthy food so he starves and then only rarely can go to McDonalds so he is very unhealthy—and how messed up this cycle is” | 2/10 Key Quote: “Not having enough money to provide healthy food” | 1/10 Key Quote: “The biggest lesson is to eat right” | 1/10 Key Quote: “About a black boy eating McDonalds and his father gets shot and he starts crying cause he broke and live in the hood” |

| 3. Health Justice Manifesto | Policy call to action to address the Type 2 diabetes epidemic by challenging the government and corporations and advocating for the public’s health rights | Documentary/Anthem (Social Justice, Autonomy and Empowerment) | 6/9 Key Quote: “About young people encouraging others to eat healthy and fight for health rights”One participant did not respond to questions pertaining to this video | 1/9 Key Quote: “This video was about how liquor stores are in neighborhoods and grocery stores isn’t which makes people buy unhealthy food from liquor stores” | 1/9 Key Quote(s): “It’s much more likely for young people to get diabetes these days” | 1/9 Key Quote: “A knock off of a commercial I saw about not drinking at a party” |

| 4. Block O’ Breakfast | Food and beverage industries utilize deceptive marketing and false advertisements to sell unhealthy, sugary and processed foods to young people. | Comedic Parody (Defiance) | 3/10 Key Quote: “This videos was about how they advertise unhealthy food and that everything is not what it seems” | 5/10 Key Quote(s): “How corporations pay the fee to be able to put all that junk in our neighborhood” | 2/10 Key Quote: “bad breakfast that kids eat and what the effects can lead to” | 0/10 N/A |

| 5. Sole Mate | Prolonged, unmanaged Type 2 diabetes can lead to severe consequences, such as amputation of limbs. Increasing awareness can help prevent diabetes-related complications. | Horror (Social Justice) | 7/10 Key Quote(s): “About diabetes causing amputation of body parts” | 0/10 N/A | 1/10 Key Quote(s): “stay healthy” | 2/10 Key Quote: “How grateful we should be to be able to walk, but also to stop wars. There was too many messages” |

| 6. Farm Livin’ | We, as consumers, are clueless to what is happening behind the scenes of industrialized foods; we are being “fed” by profit-hungry corporations—like farm animals. | Documentary (Defiance) | 3/9 Key Quote: “What people are eating, and what they do to the farm food for the consumers”One participant did not respond | 3/9 Key Quote: “We don’t know what we eat or what we are putting in our body” | 2/9 Key Quote: “We as consumers are just as bad as what we consume” | 1/9 Key Quote: “About a rapper that’s chunky” |

| 7. Death Recipe | Slavery and other forms of historical or contemporary forms of oppression shape dietary norms. Food addiction is a response to the stress and mental health problems that accompany oppression. Obesity and body image disorders are a result. | Autobiography/Testimonial (Social Justice and Defiance) | 4/10 Key Quote: “How diabetes can be a part of culture or a family” | 3/10 Key Quote: “a young lady who’s fed up about the way food is” | 1/10 Key Quote: “how young people dying at a younger age from diabetes” | 2/10 Key Quote: “not so clear” |

| 8. Quantum Field | Trying to be healthy in an environment not conducive to healthy living feels like living in a nightmare. | Suspense (Defiance) | 2/9 Key Quote: “our addiction to fast food is real. So much so, it’s odd when we wanna be healthy”One participant did not respond | 1/9 Key Quote: “How it’s hard to escape diabetes… but possible” | 1/9 Key Quote: “About unhealthy eating habits” | 5/9 Key Quote: “that there’s good and bad people” |

| 9. The Corner | Inaccessibility of healthy food options in low-income neighborhoods makes “choice” an illusion. | Testimonial (Social Justice and Autonomy) | 3/8 Key Quote(s): “corner store convenience boost risks of diabetes”Two participants did not respond to questions pertaining to this video | 1/8 Key Quote: “The dilemma between junk food and healthy food” | 2/8 Key Quote: “all that unhealthy food is leading to diabetes” | 2/8 Key Quote: “It was about a dude at a grocery store” |

| Primary Public Health Themes | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Individual Behaviors | “I can blame you for having diabetes, but you can win because it’s your way of living. That’s how you want to live because if you want to live like a hoarder, go ahead. If you want to live this way, it’s your choice to live. That’s why I say it’s within the individual” |

| Built Environment | “We know it’s the individual’s responsibility, but where restaurants are compared to where grocery stores is like strategically placed” |

| “This video was about how liquor stores are in neighborhoods and grocery stores isn’t, which makes (our) people buy unhealthy food from liquor stores.” | |

| Financial Barriers and Competing Demands | “These kids are hungry and they only go to certain places for food ‘cause that’s where they go. So if a kid only goes to the corner store because their parents don’t cook and there’s no grocery store close by, what are they supposed to do? They can go to a corner store for a $0.99 cent bag of chips… it’s convenient but it’s not good.” |

| Institutional Factors: Deceptive Marketing | “I mean it shows how I look at it… behind the scenes of the commercials of the food or… the advertisement of the food.” |

| Underlying Sociopolitical Themes | Representative Quotes |

| Entrapment vs. Liberation | “Even if people wanted to be healthy they don’t have the opportunity to go about it like financially or physically because they have nowhere to go.” |

| “I want us to leave out of here with help and whatever we can.” | |

| Powerlessness vs. Empowerment | “It’s… much bigger than our own so we can’t and—I hate to say it—that we can’t really do anything. We write as many letters to the government as we want, but they’re not going to take these liquor stores that have been here since I was a child. I’m sure somebody complained about them, they’re still here.” |

| “I’m going to go tell somebody because it seems like—I didn’t used to know why the life expectancy of African American people was shorter that white people, but now that look at all the factors, it starting to make sense to me. So if you tell somebody else, maybe they want to eat healthier or something like that or maybe they have a better idea than me.” | |

| “(Let’s) start a garden in your community… (so) we have fresh produce in our garden. I mean we have in our garden, fresh produce I’d say that’s what I can think of like community-wise” | |

| Cultural Determinism vs. Cultural Relativism | “There’s a lot of cultures that have things that Americans will look at and be like “Ugh! Why would you eat that?” but that’s their culture regardless if it’s healthy or not so it’s kind of for Black People, that’s our culture so, for you to say it’s unhealthy… It’s so offensive.” |

| “I don’t like that… For the same reason, it was kind of tedious too and it’s like, “Okay, we know, Black people know.” That it’s not usually the healthiest thing to eat, but that’s culture.” |

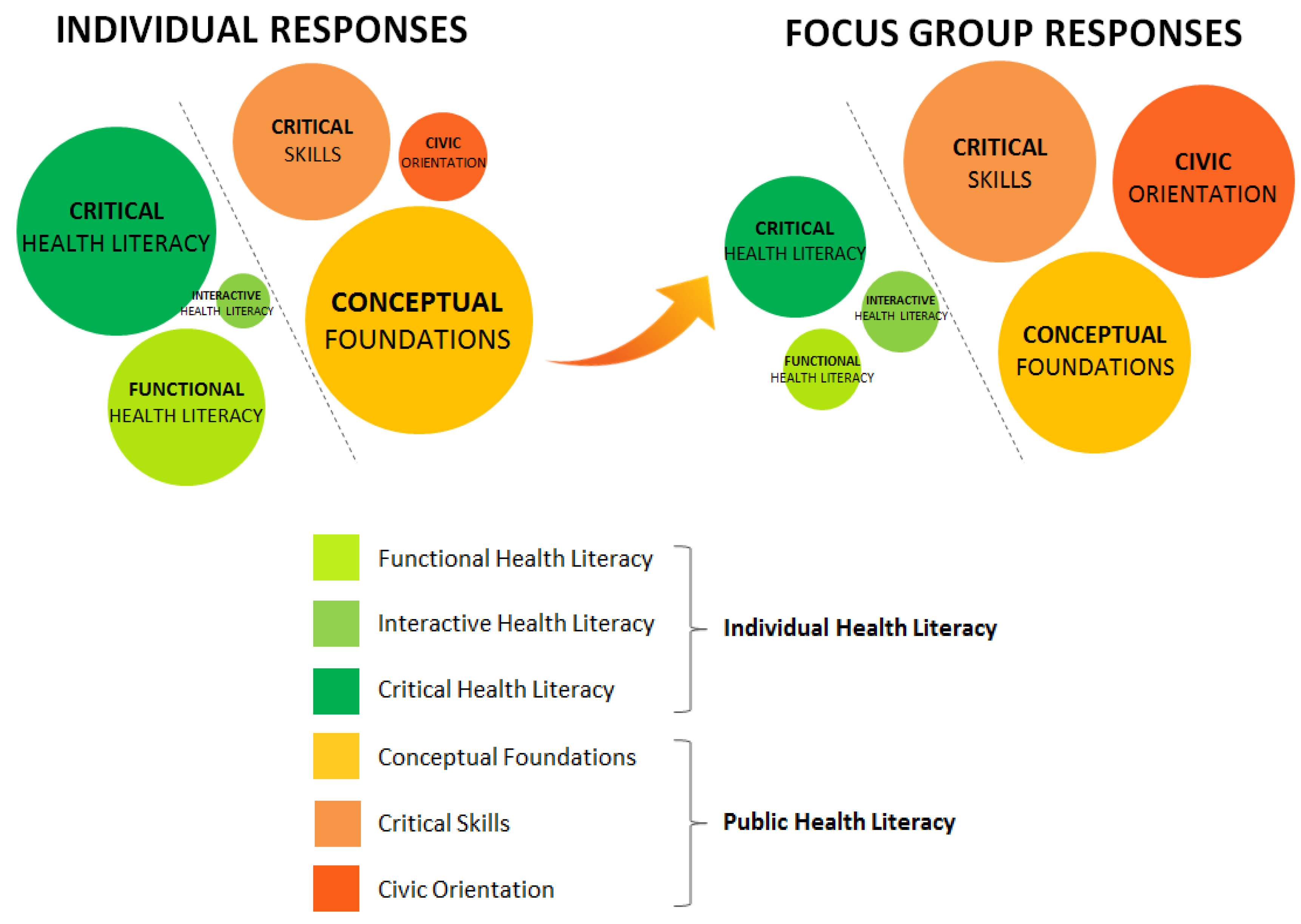

| Dimensions of Health Literacy | Individual Health Literacy Dimensions of Individual Health Literacy (Nutbeam, 2006): Functional, Interactive, and Critical Health Literacy | Public Health Literacy Dimensions of Public Health Literacy (Freedman, 2009): Conceptual Foundations, Critical Skills, and Civic Orientation |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Foundations | Theme: Built Environment (Please confirm whether the bold is necessary.)

| |

| Functional Health Literacy | Theme: Individual Behaviors

| |

| Interactive Health Literacy | Theme: Empowerment

| |

| Critical Skills | Theme: Institutional Factors: Deceptive Marketing

| Theme: Liberation

|

| Civic Orientation | Theme: Empowerment

| |

| Conceptual Foundations | Theme: Built Environment

| |

| Functional Health Literacy | Theme: Individual Behaviors

| |

| Interactive Health Literacy | Theme: Empowerment

| |

| Critical Skills | Theme: Liberation

| Theme: Entrapment

|

| Civic Orientation | Theme: Empowerment

|

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schillinger, D.; Tran, J.; Fine, S. Do Low Income Youth of Color See “The Bigger Picture” When Discussing Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Public Health Literacy Campaign. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050840

Schillinger D, Tran J, Fine S. Do Low Income Youth of Color See “The Bigger Picture” When Discussing Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Public Health Literacy Campaign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(5):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050840

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchillinger, Dean, Jessica Tran, and Sarah Fine. 2018. "Do Low Income Youth of Color See “The Bigger Picture” When Discussing Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Public Health Literacy Campaign" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 5: 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050840