Mechanism of the Formation of Electronically Excited Species by Oxidative Metabolic Processes: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Role of ROS in the Formation of Electronically Excited Species

2.1. Superoxide Anion Radical

2.1.1. Formation

2.1.2. Oxidizing Property

2.2. Hydrogen Peroxide

2.2.1. Formation

2.2.2. Oxidizing Property

2.3. Hydroxyl Radical

2.3.1. Formation

2.3.2. Oxidizing Property

2.4. Singlet Oxygen

2.4.1. Formation

2.4.2. Oxidizing Property

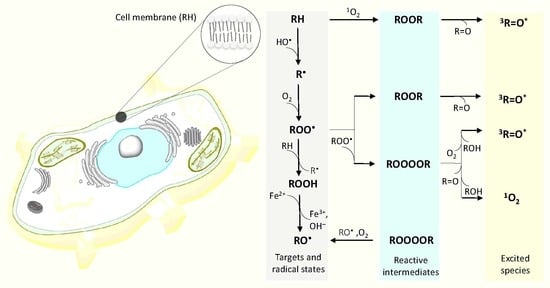

3. Mechanism of the Formation of Electronically Excited States

3.1. Organic Radicals

3.2. High-Energy Intermediates

3.2.1. 1,2-Dioxetane

3.2.2. Tetroxide

3.3. Electronically Excited States

3.3.1. Triplet Carbonyl

3.3.2. Chromophore

3.3.3. Singlet Oxygen

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radical in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 704. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B. Free radicals and antioxidants-Quo vadis? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, C.L.; Davies, M.J. Generation and propagation of radical reactions on proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerget. 2001, 1504, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tulah, A.S.; Birch-Machin, M.A. Stressed out mitochondria: The role of mitochondria in ageing and cancer focussing on strategies and opportunities in human skin. Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeller-Schoen, S.; Steven, S.; Kossmann, S.; Scholz, A.; Daub, S.; Oelze, M.; Xia, N.; Hausding, M.; Mikhed, Y.; Zinssius, E.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of the Crosstalk Between Mitochondria and NADPH Oxidase Through Reactive Oxygen Species-Studies in White Blood Cells and in Animal Models. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R. Peroxynitrite, a Stealthy Biological Oxidant. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26464–26472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartesaghi, S.; Radi, R. Fundamentals on the biochemistry of peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: Redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5839–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C.; Halliwell, B. Free radicals and antioxidants in the year 2000—A historical look to the future. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 899, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. The definition and measurement of antioxidants in biological systems. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, L.; Corstjens, H.; Neven, A.; Declercq, L.; Maes, D. Antioxidant enzyme activity in human stratum corneum shows seasonal variation with an age-dependent recovery. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 120, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auf Dem Keller, U.; Kumin, A.; Braun, S.; Werner, S. Reactive oxygen species and their detoxification in healing skin wounds. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2006, 11, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvin, M.E.; Patzelt, A.; Knorr, F.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Sterry, W.; Lademann, J. One-year study on the variation of carotenoid antioxidant substances in living human skin: Influence of dietary supplementation and stress factors. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008, 13, 044028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Mishra, P.C. Urocanic acid as an efficient hydroxyl radical scavenger: A quantum theoretical study. J. Mol. Model. 2011, 17, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, S.; Davies, M.J.; Dean, R.T. Protein oxidation and ageing. Exp. Gerontol. 2001, 36, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celaje, J.A.; Zhang, D.; Guerrero, A.M.; Selke, M. Chemistry of trans-Resveratrol with Singlet Oxygen: 2+2 Addition, 4+2 Addition, and Formation of the Phytoalexin Moracin M. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4846–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, M.D. Reactive oxygen species and programmed cell death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996, 21, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.F.; Robinson, M.K.; Baron, E.D.; Cooper, K.D. Skin immune systems and inflammation: Protector of the skin or promoter of aging? J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2008, 13, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilento, G.; Adam, W. From free radicals to electronically excited species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 19, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, C.M.; Prado, F.M.; Massari, J.; Ronsein, G.E.; Martinez, G.R.; Miyamoto, S.; Cadet, J.; Sies, H.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Bechara, E.J.H.; et al. Excited singlet molecular O-2 ((1)Delta g) is generated enzymatically from excited carbonyls in the dark. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifra, M.; Pospíšil, P. Ultra-weak photon emission from biological samples: Definition, mechanisms, properties, detection and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 139, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Pospisil, P. Towards the two-dimensional imaging of spontaneous ultra-weak photon emission from microbial, plant and animal cells. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madl, P.; Verwanger, T.; Geppert, M.; Scholkmann, F. Oscillations of ultra-weak photon emission from cancer and non-cancer cells stressed by culture medium change and TNF-alpha. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rac, M.; Sedlarova, M.; Pospisil, P. The formation of electronically excited species in the human multiple myeloma cell suspension. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; van Wijk, E.; van Wietmarschen, H.; Wang, M.; Sun, M.M.; Koval, S.; van Wijk, R.; Hankemeier, T.; van der Greef, J. Spontaneous ultra-weak photon emission in correlation to inflammatory metabolism and oxidative stress in a mouse model of collagen-induced arthritis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2017, 168, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.; Ferretti, U.; Sedlarova, M.; Pospisil, P. Singlet oxygen production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, S.; Tada, M.; Kobayashi, M. Non-invasive visualization of physiological changes of insects during metamorphosis based on biophoton emission imaging. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.; Van Wijk, E. Ultraweak Photon Emission from Human Body; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Biesalski, H.K.; Obermueller-Jevic, U.C. UV light, beta-carotene and human skin-Beneficial and potentially harmful effects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 389, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, O.Y.; Stamatas, G.; Saliou, C.; Kollias, N. A chemiluminescence study of UVA-induced oxidative stress in human skin in vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 122, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Rattan, S.I.S.; Fernandes, R.A.; Demirovic, D.; Dymek, B.; Lima, C.F. Heat stress and hormetin-induced hormesis in human cells: Effects on aging, wound healing, angiogenesis, and differentiation. Dose-response 2009, 7, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Kikuchi, D.; Okamura, H. Imaging of Ultraweak Spontaneous Photon Emission from Human Body Displaying Diurnal Rhythm. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Pospisil, P. Linoleic Acid-Induced Ultra-Weak Photon Emission from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a Tool for Monitoring of Lipid Peroxidation in the Cell Membranes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Pospisil, P. Two-dimensional imaging of spontaneous ultra-weak photon emission from the human skin: Role of reactive oxygen species. J. Biophotonics 2011, 4, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, A.; Pospíšil, P. Production of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical in potato tuber during the necrotrophic phase of hemibiotrophic pathogen Phytophthora infestans infection. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2012, 117, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, R.C.R.; Schoeman, J.C.; van Winden, L.J.; Cervinkova, K.; Ramautar, R.; Van Wijk, E.P.A.; Cifra, M.; Berger, R.; Hankemeier, T.; van der Greef, J. Ultra-weak photon emission as a dynamic tool for monitoring oxidative stress metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, A.M.; Komatsu, S. Proteins involved in biophoton emission and flooding-stress responses in soybean under light and dark conditions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016, 43, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, E.; Arad, I.D.; Boveris, A.; Fisher, A.B.; Chance, B. Partial Spectral-Analysis of the Hydroperoxide-Induced Chemi-Luminescence of the Perfused Lung. FEBS Lett. 1980, 111, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, R.; Ackerman, J.M.; Van Wijk, E.P.A. Color filters and human photon emission: Implications for auriculomedicine. Explor. J. Sci. Heal. 2005, 1, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E.; Wefers, H.; Sies, H. Low-Level Chemi-Luminescence of Isolated Hepatocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1981, 119, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, B.G.; Roy, D. Weak luminescence from the frozen-thawed root tips of Cicer arietinum L. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1992, 12, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P.; Prasad, A.; Rác, M. Role of reactive oxygen species in ultra-weak photon emission in biological systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 139, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Williams, E.; Cadenas, E. Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem. J. 2001, 353, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auchere, F.; Rusnak, F. What is the ultimate fate of superoxide anion in vivo? J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 7, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospisil, P. Molecular mechanisms of production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerget. 2012, 1817, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asada, K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, M.J.; Kay, C.J. Superoxide production during reduction of molecular oxygen by assimilatory nitrate reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 326, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, A.J.; Brand, M.D. Superoxide production by NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) depends on the pH gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Biochem. J. 2004, 382, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.M. The potential diagram for oxygen at PH-7. Biochem. J. 1988, 253, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikens, J.; Dix, T.A. Perhydroxyl radical (HOO.) initiated lipid-peroxidation-the role of fatty acid hydroperoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15091–15098. [Google Scholar]

- Gebicki, J.M.; Bielski, B.H.J. Comparison of the capacities of the perhydroxyl and the speroxide radicals to initiate chain oxidation of linoleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 7020–7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Kettle, A.J. Radical-radical reactions of superoxide: A potential route to toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 305, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbouti, A.; Doulias, P.T.; Zhu, B.Z.; Frei, B.; Galaris, D. Intracellular iron, but not copper, plays a critical role in hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, C.; Karlsson, A.; Bylund, J. Measurement of respiratory burst products generated by professional phagocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 412, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daithankar, V.N.; Wang, W.; Trujillo, J.R.; Thorpe, C. Flavin-linked Erv-family sulfhydryl oxidases release superoxide anion during catalytic turnover. BioChemistry 2012, 51, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, P.M. The 2 Redox Potentials for Oxygen Reduction to Superoxide. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1987, 12, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culotta, V.C.; Yang, M.; O’Halloran, T.V. Activation of superoxide dismutases: Putting the metal to the pedal. Biochim. Biophysica Acta-Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halliwell, B.; Clement, M.V.; Long, L.H. Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kale, R.; Hebert, A.E.; Frankel, L.K.; Sallans, L.; Bricker, T.M.; Pospíšil, P. Amino acid oxidation of the D1 and D2 proteins by oxygen radicals during photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2988–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffmann, M.E.; Meneghini, R. Action of hydrogen peroxide on human fibroblast in culture. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1979, 30, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtman, E.R.; Levine, R.L. Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino Acids 2003, 25, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Berry, A.H.; Spencer, D.S.; Stites, W.E. Comparing the effect on protein stability of methionine oxidation versus mutagenesis: Steps toward engineering oxidative resistance in proteins. Protein Eng. 2001, 14, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.T.; Nagy, P. On the kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of cysteine and hydrogen peroxide in aqueous solution-Commentary. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winterbourn, C.C. Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: The Fenton reaction. Toxicol. Lett. 1995, 82–83, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prousek, J. Fenton chemistry in biology and medicine. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 2325–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, G.R. The pecking order of free-radicals and antioxidants-lipid-peroxidation, alpha-tocopherol, and ascorbate. Arch. BioChem. Biophys. 1993, 300, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, J.L.; Fontecave, M. Iron and activated oxygen species in biology: The basic chemistry. Biometals 1999, 12, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresgen, N.; Jaksch, H.; Lacher, H.; Ohlenschlager, I.; Uchida, K.; Eckl, P.M. Iron-mediated oxidative stress plays an essential role in ferritin-induced cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldo, G.S.; Wright, E.; Whang, Z.H.; Briat, J.F.; Theil, E.C.; Sayers, D.E. Formation of the ferritin iron mineral occurs in plastids-an X-ray-absorption spectroscopy study. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Butler, J.; Vanleeuwen, J.W. Haber-Weiss Cycle. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1978, 28, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophysica Acta-Bioenerget. 2009, 1787, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stadtman, E.R. Oxidation of free amino-acids and amino-acid-residues in proteins by radiolysis and by meral-catalyzed reactions. Annu. Rev. BioChem. 1993, 62, 797–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, A.E.; Eveleigh, J.F. Mechanisms of DNA oxidation. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1999, 222, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Pogozelski, W.K.; Tullius, T.D. DNA strand breaking by the hydroxyl radical is governed by the accessible surface areas of the hydrogen atoms of the DNA backbone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 9738–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pogozelski, W.K.; Tullius, T.D. Oxidative strand scission of nucleic acids: Routes initiated by hydrogen abstraction from the sugar moiety. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henle, E.S.; Linn, S. Formation, prevention, and repair of DNA damage by iron hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 19095–19098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B.; Aruoma, O.I. DNA damage by oxygen-derived species-its mechanism and measurement in mammalian systems. FEBS Lett. 1991, 281, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilby, P.R. Singlet oxygen: There is indeed something new under the sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3181–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRosa, M.C.; Crutchley, R.J. Photosensitized singlet oxygen and its applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 233, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, W.; Cilento, G. Chemical and Biology Generation of Excited States; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, W.; Kazakov, D.V.; Kazakov, V.P. Singlet-oxygen chemiluminescence in peroxide reactions. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, S.P.; Liebler, D.C. Determination of singlet oxygen-specific versus radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in photosensitized oxidation of lipid bilayers: Effect of beta-carotene and alpha-tocopherol. BioChemistry 1997, 36, 12911–12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracanin, M.; Hawkins, C.L.; Pattison, D.I.; Davies, M.J. Singlet-oxygen-mediated amino acid and protein oxidation: Formation of tryptophan peroxides and decomposition products. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, W.A.; Stanley, J.P.; Blair, E.; Cullen, G.B. Autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty-acids. 1. effect of ozone on autoxidation of neat methyl linoleate and methyl linolenate. Arch. Environ. Health 1976, 31, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, P.; Tonucci, L.; d’Alessandro, N.; Morvillo, A.; Sortino, S.; Bressan, M. Water-Soluble Transition-Metal-Phthalocyanines as Singlet Oxygen Photosensitizers in Ene Reactions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbeck, A.G.; de Kiff, A. A New Directing Mode for Singlet Oxygen Ene Reactions: The Vinylogous Gem Effect Enables a O-1(2) Domino Ene/ 4+2 Process. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 2073–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravanat, J.L.; Di Mascio, P.; Martinez, G.R.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Cadet, J. Singlet oxygen induces oxidation of cellular DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40601–40604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunoda, H.; Kudo, T.; Masaki, Y.; Ohkubo, A.; Seio, K.; Sekine, M. Biochemistry behavior of N-oxidized cytosine and adenine bases in DNA polymerase-mediated primer extension reactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 2995–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, K.V.; Muller, J.G.; Burrows, C.J. Oxidation of 9-beta-D-ribofuranosyl uric acid by one-electron oxidants versus singlet oxygen and its implications for the oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Foote, C.S. Formation of transient intermediates in low-temperature photosensitized oxidation of an 8-C-13-guanosine derivative. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 4865–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, F.; Houk, K.N.; Foote, C.S. Effect of guanine stacking on the oxidation of 8-oxoguanine in B-DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatz, S.; Poulsen, L.; Ogilby, P.R. Time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence measurements from photosensitized experiments in single cells: Effects of oxygen diffusion and oxygen concentration. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, E.F.F.; Pedersen, B.W.; Breitenbach, T.; Toftegaard, R.; Kuimova, M.K.; Arnaut, L.G.; Ogilby, P.R. Irradiation-and Sensitizer-Dependent Changes in the Lifetime of Intracellular Singlet Oxygen Produced in a Photosensitized Process. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbach, T.; Kuimova, M.K.; Gbur, P.; Hatz, S.; Schack, N.B.; Pedersen, B.W.; Lambert, J.D.C.; Poulsen, L.; Ogilby, P.R. Photosensitized production of singlet oxygen: Spatially-resolved optical studies in single cells. Photochem. PhotoBiol. Sci. 2009, 8, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mascio, P.; Martinez, G.R.; Miyamoto, S.; Ronsein, G.E.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Cadet, J. Singlet Molecular Oxygen Reactions with Nucleic Acids, Lipids, and Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2043–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girotti, A.W. Lipid hydroperoxide generation, turnover, and effector action in biological systems. J. Lipid Res. 1998, 39, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leach, A.G.; Houk, K.N.; Foote, C.S. Theoretical Prediction of a Perepoxide Intermediate for the Reaction of Singlet Oxygen with trans-Cyclooctene Contrasts with the Two-Step No-Intermediate Ene Reaction for Acyclic Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8511–8519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, R.T.; Gieseg, S.; Davies, M.J. Reactive Species and Their Accumulation on Radical-Damaged Proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1993, 18, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.A.; Narita, S.; Gieseg, S.; Gebicki, S.; Gebicki, J.M.; Dean, R.T. Long-lived reactive species on free-radical-damaged proteins. Biochem. J. 1992, 282, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greer, A.; Vassilikogiannakis, G.; Lee, K.C.; Koffas, T.S.; Nahm, K.; Foote, C.S. Reaction of singlet oxygen with trans-4-propenylanisole. Formation of 2+2 products with added acid. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 6876–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, G.F.; Trofimov, A.V.; Vasil’ev, R.F.; Veprintsev, T.L. Peroxy-radical-mediated chemiluminescence: Mechanistic diversity and fundamentals for antioxidant assay. Arkivoc 2007, 8, 163–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemi, M.; Ronsein, G.E.; Miyamoto, S.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Di Mascio, P. Generation of Cholesterol Carboxyaldehyde by the Reaction of Singlet Molecular Oxygen O-2 ((1)Delta(g)) as Well as Ozone with Cholesterol. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clennan, E.L. New mechanistic and synthetic aspects of singlet oxygen chemistry. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 9151–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, W.; Bosio, S.G.; Turro, N.J. Highly diastereoselective dioxetane formation in the photooxygenation of enecarbamates with an oxazolidinone chiral auxiliary: Steric control in the 2+2 cycloaddition of singlet oxygen through conformational alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8814–8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clennan, E.L.; Pace, A. Advances in singlet oxygen chemistry. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 6665–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, E.J.; Wang, Z. Conversion of arachidonic acid to the prostaglandin endoperoxide PGG(2), a chemical analog of the biosynthetic-pathway. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Rettori, D.; Augusto, O.; Martinez, G.R.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Di Mascio, P. Linoleic acid hydroperoxide reacts with hypochlorite generating peroxyl radical intermediates and singlet oxygen. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, S16. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, F.M.; Oliveira, M.C.B.; Miyamoto, S.; Martinez, G.R.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Ronsein, G.E.; Di Mascio, P. Thymine hydroperoxide as a potential source of singlet molecular oxygen in DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, G.A. Deuterium-isotope Effects in the Autoxidation of Aralkyl Hydrocarbons. Mechanism of the Interaction of Peroxy Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 3871–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Martinez, G.R.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; Di Mascio, P. Singlet molecular oxygen generated by biological hydroperoxides. J. PhotoChem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 139, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Di Mascio, P. Lipid Hydroperoxides as a Source of Singlet Molecular Oxygen. In Lipid Hydroperoxide-Derived Modification of Biomolecules; Kato, Y., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 77, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas, E.; Sies, H. Formation of electronically excited states during the oxidation of arachidonic acid by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.; Chamulitrat, W.; Takahashi, N.; Chignell, C.; Mason, R. Detection of Singlet oxygem phosphorescence during chloroperoxidase-catalyzed decomposition of ethyl hydroperoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 7900–7906. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.A.; Ingold, K.U. Absolute rate constants for hydrocarbon autooxidation.V. Hydroperoxy radical in chain propagation and termination. Can. J. Chem. 1967, 45, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilento, G.; Nascimento, A. Generation of electronically excited triplet species at the cellular level: A potential source of genotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 1993, 67, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A.; Cadenas, E.; Reiter, R.; Filipkowski, M.; Nakase, Y.; Chance, B. Organ Chemi-Luminescence-Non-Invasive Assay for Oxidative Radical Reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.; Mehta, M.; Grant, M. Biophoton imaging: A nondestructive method for assaying R gene responses. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005, 18, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmanyan, A.P.; Foote, C.S. Solvent effects on singlet oxygen yield from N,PI-asterisk and PI,PI-asterisk triplet carbonyl compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 5032–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, J.W. Biophoton distress flares signal the onset of the hypersensitive reaction. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, E.P.; Mau, A.W.H.; Ghiggino, K.P. Dye-Sensitized Photooxidation of Anthracene and Its Derivatives in Nafion Membrane. Aust. J. Chem. 1991, 44, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilento, G.; Adam, W. Photochemistry and Photobiology without Light. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1988, 48, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopecky, K.R.; Mumford, C. Luminescence in thermal decomposition of 3,3,4-trimethyl-1,2-dioxetane. Can. J. Chem. 1969, 47, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilento, G.; Debaptista, C.; Brunetti, I.L. Triplet carbonyls: From photophysics to biochemistry. J. Mol. Struct. 1994, 324, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecky, K.R.; Filby, J.E. Yields of excited-states from thermolysis of some 1,2-dioxetanes. Can. J. Chem. 1979, 57, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turro, N.J.; Lechtken, P. Biacetyl sensitized decomposition of tetramethyl-1,2-dioxetane-example of anti-Stokes sensitization involving a masked excited state. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973, 14, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M. Advanced chemistry of dioxetane-based chemiluminescent substrates originating from bioluminescence. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2004, 5, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.H.; Anderegg, J.H.; Price, M.E.; Tappen, W.A.; Oneal, H.E. Kinetics and mechanisms of thermal decomposition of triphenyl-1,1,2-dioxetane. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 2236–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasaka, T.; Fukuoka, K.; Ando, W. A 3-methylene-1,2-dioxetane as a possible chemiluminescent intermediate in singlet oxygenation of allene. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1989, 62, 1367–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumstark, A.L.; Anderson, S.L.; Sapp, C.J.; Vasquez, P.C. Thermolysis of 3-alkyl-3-methyl-1,2-dioxetanes: Activation parameters and chemiexcitation yields. Heteroat. Chem. 2001, 12, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, A.L.P.; Weiss, D.; Catalani, L.H.; Baader, W.J. Studies on the intramolecular electron transfer catalyzed thermolysis of 1,2-dioxetanes. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 5317–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, F.; Sundberg, R. Advanced Organic Chemisty Part A Structure and Mechanisms; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 1199. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, S.; Ronsein, G.E.; Prado, F.M.; Uemi, M.; Correa, T.C.; Toma, I.N.; Bertolucci, A.; Oliveira, M.C.B.; Motta, F.D.; Medeiros, M.H.G.; et al. Biological hydroperoxides and singlet molecular oxygen generation. IUBMB Life 2007, 59, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vacher, M.; Galvan, I.F.; Ding, B.W.; Schramm, S.; Berraud-Pache, R.; Naumov, P.; Ferre, N.; Liu, Y.J.; Navizet, I.; Roca-Sanjuan, D.; et al. Chemi-and Bioluminescence of Cyclic Peroxides. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6927–6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusto, O.; Cilento, G. Dark Excitation of Chlorophyll. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1979, 30, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohne, C.; Campa, A.; Cilento, G.; Nassi, L.; Villablanca, M. Chlorophyll-an efficient detector of electronically excited species in Biochem. systems. Anal. BioChem. 1986, 155, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, A.; Nassi, L.; Cilento, G. Triplet Energy-Transfer to Chloroplasts from Peroxidase-Generated Excited Aliphatic-Aldehydes. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1984, 40, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, J.B.; Droppa, M.; Caspi, V.; Raskin, V.I.; Horvath, G. Light-independent thermoluminescence from thylakoids of greening barley leaves. Evidence for involvement of oxygen radicals and free chlorophyll. Physiol. Plant. 1998, 104, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcal, G.; Bertolotti, S.G.; Previtah, C.M.; Encinas, M.V. Electron transfer quenching of singlet and triplet excited states of flavins and lumichrome by aromatic and aliphatic electron donors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 4123–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovsky, A.A.; Neverov, K.V.; Egorov, S.Y.; Roeder, B.; Levald, T. Photophysical Studies of Pheophorbide-a and Pheophytin-a Phosphorescence and Photo-Sensitized Singlet Oxygen Luminescence. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1990, 5, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ojeda, F.; Calcerrada, M.; Ferrero, A.; Campos, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, C. Measuring the Human Ultra-Weak Photon Emission Distribution Using an Electron-Multiplying, Charge-Coupled Device as a Sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchida, K.; Iwasa, T.; Kobayashi, M. Noninvasive imaging of UV-induced oxidative stress in human skin using ultra-weak photon emission. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, B20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Iwasa, T.; Tada, M. Polychromatic spectral pattern analysis of ultra-weak photon emissions from a human body. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 159, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.; Balukova, A.; Pospisil, P. Triplet Excited Carbonyls and Singlet Oxygen Formation During Oxidative Radical Reaction in Skin. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hideg, E.; Inaba, H. Biophoton Emission (Ultraweak Photoemission) from Dark Adapted Spinach-Chloroplasts. PhotoChem. Photobiol. 1991, 53, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Goltsev, V.; Bosa, K.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Strasser, R.J.; Govindjee. Experimental in vivo measurements of light emission in plants: A perspective dedicated to David Walker. Photosynth. Res. 2012, 114, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R.E. Mechanism of chemiluminescence from peroxy radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 5433–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.J.; Mendenhall, G.D. Yields of singlet molecular oxygen from peroxyl radical termination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanofsky, J.R. Singlet oxygen production from the peroxidase catalyzed formation of styrene glutathione adducts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1989, 159, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Bao, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, X. Singlet oxygen generation from the decomposition of alpha-linolenic acid hydroperoxide by cytochrome c and lactoperoxidase. BioChemstry 2007, 46, 6668–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, E.; Fluhr, R. Singlet oxygen detection in biological systems: Uses and limitations. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1192742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pospíšil, P.; Prasad, A.; Rác, M. Mechanism of the Formation of Electronically Excited Species by Oxidative Metabolic Processes: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9070258

Pospíšil P, Prasad A, Rác M. Mechanism of the Formation of Electronically Excited Species by Oxidative Metabolic Processes: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(7):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9070258

Chicago/Turabian StylePospíšil, Pavel, Ankush Prasad, and Marek Rác. 2019. "Mechanism of the Formation of Electronically Excited Species by Oxidative Metabolic Processes: Role of Reactive Oxygen Species" Biomolecules 9, no. 7: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9070258