1. Introduction

As

Greely (

2008) chronicles, commercial genetic genealogy testing developed in the wake of the mapping of the human genome, which culminated in 2003. Among many other things, this mapping determined that only a small percentage of a person’s genetic mutations or markers can be used to sort members of the species according to the geographic origins of their progenitors. When this testing ventured beyond examining DNA linked to the direct paternal (Y-DNA) and maternal (mitochondrial/MtDNA) lineages, each of which establishes distant ancestry along only one of the multitudinous genetic lines of an individual, autosomal or admixture tests, often branded as ethnic ancestry tests, became a feature, particularly in the context of a progressively multicultural U.S. market, in which one’s identity is often expressed in hyphenated form (African-American, Italian-American, etc.). This proclivity can be viewed as both distinguishing and unifying, as echoed in the country’s motto,

E pluribus Unum (“Out of many, one”). In fact, AncestryDNA recently discontinued its Y-DNA and MtDNA testing services in favor of their autosomal ethnic ancestry tests, after which their advertising in the U.S. seemed to become more digestible and cohesive.

The autosomal procedure examines ancestry informative markers (AIMS) from throughout the genome, comparing the markers of the test subject to those of subjects from various regional populations in order to determine geographic genetic affinities. However, consumers are allowed and, in many cases, encouraged, to understand this as the determination of one’s ethnic and/or racial classification(s). The extent to which a given population has been tested can affect the accuracy of such findings. “It’s all privatized science, and the algorithms are not generally available for peer review,” remarked anthropologist Jonathan Marks from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte (quoted in

Kolata 2017). Most services initially explored such genetic affinities in terms of broad, continental designations—Asian, African, European, and Native American—that problematically parallel culturally fashioned racial groupings. By and by, subcategorization was achieved, but according to variable classification schemes that can still be associated with continental labels and which might also be influenced by culture and the profit motive. Moreover, the finer distinctions are even more debatable (see

Kolata 2017). My “ethnic ancestry” results from AncestryDNA shifted after a reassessment that jettisoned the half-moon-sized slice of Middle Eastern pie in my pie chart and replaced it, in part, with a more specific and, logically, more recently manifested genetic affinity with “Italy/Greece” that attaches me and, presumably, many of those of Italian origin like me, more securely to an identifiable region of Europe (see

Scodari 2016). As

Schramm et al. (

2012, p. 3) caution: “DNA identification is not just about the self, but always encompasses the external evaluation and organization of people in groups”.

Issues linked to ethnic and racial identity are not the only ones mobilized by genetic genealogy testing. Like conventional genealogy, genetic genealogy proceeds from a premise that biology trumps culture when it comes to establishing kinship relations, even though cultural inheritance can be a motivating factor for engaging in either approach to family history whether or not one’s kin are biologically related. I have contended that an educated interest and/or proficiency in music on one side of my family tree is in large part a cultural legacy brought about by role modeling within the family (

Scodari 2015). Despite what some studies of identical twins separated at birth purport to demonstrate, the passing down of abilities, beliefs, interests, and behavioral traits

is influenced by culture. One twin investigator, Nancy Segal, admits that environment does matter, but that the data also show that it “works in ways [the researchers] hadn’t expected” (quoted in

Lewis 2014). However, genetic genealogy discourses could steer understandings of kinship away from valuing cultural relatedness and the many forms family can take.

This essay examines advertising spots focusing on autosomal genetic ancestry testing and/or genetic matching services distributed in the U.S. by providers AncestryDNA and 23andMe in light of established and emergent issues in the arenas of ethnicity, race, hybridity, and kinship. Qualitative analysis of twenty-two 30- and 60-s ads airing in the U.S. in June through August of 2017 were considered using a method derived from the grounded theory approach to qualitative data analysis of

Glaser and Strauss (

1967), which here involves classification of the relevant content based on emergent rather than pre-determined categories and issues. The theoretical/conceptual framework outlined in this essay informed the further textual analysis of 13 examples representing the resultant categories. The salient, emergent issues include: (1) genetics vs. culture; (2) hybridity and fetishization; (3) racism and racialization; and (4) resistance. As of August 2017, the ads were available on YouTube and/or iSpot.tv and could be located by searching the name of the company and title of the ad, which are provided in the analysis. Based on these categories, critical questions arise. Do these ads emphasize biological kinship to the detriment of cultural inheritance? Does the preeminence of hybridity in the ads destabilize racial essentialism? Are the ethnicities based on hybrid ancestry culturally or historically contextualized, or are they fetishized? Are racism and racialization facilitated or hindered by images and narratives in the ads? Finally, is resistance to racial hegemony mobilized by these texts, or does the genetic genealogy industry’s exploitation of oppressive histories undermine or negate potentially empowering outcomes?

2. Concepts, Theories, and Issues

Analysis of genetic genealogy advertising related to the four categories delineated above is based on emergent issues resulting from the critical deliberation of genealogical and genetic genealogical representations and practices and the theoretical and conceptual frameworks that underpin them. Dedicated critical analyses of genetic genealogy advertising do not exist in the literature thus far, whether in terms of these frameworks or any other cultural issues.

The first framework is genetics vs. culture, where it is vital to keep in mind that despite the primacy of biological relatedness in genetic genealogy, cultural inheritance is implicated in one’s eagerness to engage in both conventional and genetic family history. The satirical mockumentary series

Family Tree created by Christopher Guest and Jim Piddock (HBO, 2013) is a case in point (see

Scodari 2016). Chris O’Dowd plays Tom Chadwick, a Brit who traces his ancestry after an aunt passes away and leaves him a box of mementos. When he visits the antique store in order to decipher a peculiar family photo from this box, the owner (Piddock) anti-essentially contends that family characteristics are as much cultural as biological and not always passed on. “My great-grandfather was German but you don’t see me annexing countries,” he quips.

Social scholars caution that predominantly genetic understandings of kinship can obscure the myriad ways authentic familial relationships develop.

Lee (

2012, pp. 32–33) interrogates this consequence of genetic genealogy by discussing repercussions in the arena of immigration. In reference to a case in which an African immigrant’s request to have his children join him in the U.S. after their mother’s death was denied because of DNA test results, Lee maintains: “Genetic analysis does not always provide unwavering answers to how people are related” or to “how they understand their attachments to one another”. In arguing that the “genealogical imaginary…functions as a tool through which the ties of kinship can be both acknowledged

and disavowed,”

Kramer (

2011, p. 393) insinuates that culture can supersede the bonds of biology. In interrogating geneticist Bryan

Sykes’s (

2001) book

The Seven Daughters of Eve, which imagines the lives of the seven “clan mothers” to which most Europeans can genetically link their maternal lineages,

Nash (

2004, p. 20) maintains that the “supposedly universal and universally honoured feminine maternal essence is called on to deflect attention from the dangers of prioritizing biological connection,” as “both maternity and geneticized identities are simultaneously naturalized”.

With respect to the second category, hybridity and fetishization, autosomal genetic genealogy testing frequently leads to revelations of hybridity, what

Hall (

1990, p. 225) defines as “ruptures and discontinuities” of identity, which are vital in considering depictions and meanings in genealogy texts and practices.

Hall (

1990, p. 235) specifically describes diasporic identities not by “essence or purity, but…by a conception of ‘identity’ which lives with and through, not despite, difference; by

hybridity”.

Tyler’s (

2005) research features conventional genealogy’s role in revealing mixed-race background which, she contends, enables opposition to “the essentialist folk conception of racial difference” (1).

Squires (

2010, p. 211) declares hybridity to be the “liminal space where negotiation and struggle occur”.

Valdivia (

2011, p. 54), however, emphasizes the “need to explore the gains and losses incurred in cultural and population mixtures rather than [to] acritically celebrate mixture,” as commercial imperatives, such as those mobilized in the marketing of genetic ancestry, dictate. Similarly, in analyzing the “multiracial ambiguity” of film actor Keanu Reeves and its postmodern tendency to unsettle ideological meanings,

Sim (

2014, p. 147) points to the 18 November 1993, cover of

Time Magazine, in which a computer-generated image of a woman called “Eve,” created as a composite of persons representing 14 different racial groups, was offered as a backdrop for content relating to the impact of immigration and entitled “The New Face of America”. According to Sim, Eve functioned as a fetishized commodity, as “Asian advertisers searching for cosmopolitan, international looks that locals could still accept and identify with, began using Eurasian faces…” (

Sim 2014, p. 179).

Fetishization is a pitfall associated with the establishment of hybridity through conventional or genetic genealogy. Certainly, in terms of traditional genealogy, family artifacts can serve a fetishizing function in their shorthand signification of persons on the family tree and the eras or events with which they are linked. They might lead the family historian to seek deeper understanding, but often they do not. On

Family Tree, when Tom Chadwick discovers a photo of his great-grandfather in what appears to be Chinese attire, the program’s satirical portrayal of the captivation generated by the prospect of racial hybridity in the clan, such as the Chadwicks’ conflation of Asian ethnicities and cultures, insinuates that when whites confront multicultural heritage in texts and practices of family history, complexity and respect can become caricature (see

Scodari 2016). Progenitors introducing hybridity into a family tree may never be historically and culturally positioned but, instead, can function as a token representing the supposed open-mindedness of western societies. The sartorial and other accoutrements depicted in the photographs in Chadwick’s possession are themselves fetishized and made to carry the weight of history and meaning not otherwise established. Later, a photo of an American, female forebear on horseback sporting braids and unfamiliar headwear leads to suspicions of Native American ancestry. In both scenarios, the presumably ethnic adornments lead Chadwick on ill-informed, wild goose chases.

Racialization underlies the very notion of DNA testing for so-called ethnic ancestry. Thus, understanding the instruments of racialization is essential in critiquing texts and discourses of genetic genealogy. Following

Omi and Winant (

1994, pp. 55–56), who characterize racial formation as “the sociohistorical process by which racial categories are created, inhabited, transformed, and destroyed”,

Murji and Solomos (

2005, p. 1) theorize racialization as the “processes by which ideas about race are constructed, come to be regarded as meaningful, and are acted upon…”. Some scholars highlight drawbacks in embracing this anti-essentialist view of race. For example,

Watts (

2010, pp. 217–18) cautions: “Tropes of ‘race’ do indeed have a signification system that is textual and material—coded into the institutions we inhabit and the social relations regulated by them”. The middle ground, as I have argued, is to also and always account for the material effects that proceed from culturally constructed racial regimes (

Scodari 2013).

Bioethicists

Koenig et al. (

2008, p. 1), compilers of

Revisiting Race in a Genomic Age, debate the implications of genetic genealogy in which the potential to use this science as a mechanism for racism and racialization presents a serious peril. They contend that recent genetic research has “revived the idea of racial categories as proxies for biological differences”. Similarly,

Nash (

2004) charges that when scientists merely declare that racial categories are not genetically coded but socially constituted, they sidestep their duty to warn when it comes to the misuses and abuses of genetic genealogy.

Smart et al. (

2012, p. 49) assert that “racialization is not simply a ‘problematic outcome’ of biomedical science but also appears to play a significant role in shaping the very contours of the subject which scientists are struggling to better comprehend”. The producers of media texts that depict genetic ancestry testing but fail to adequately explain and counsel about this threat are similarly implicated.

Racialization is illustrated in Dominican Raquel

Cepeda’s (

2013) memoir,

Bird of Paradise, which reflects her efforts to “become Latina” in the U.S., a nation in which the very terms Latina, Latino, and Hispanic are racialized designations that evoke language, regions of origin, diasporic identities, and/or particular racial mixtures. Indeed,

Valdivia (

2011, p. 53) defines the process of

Latinidad as “being, becoming, and/or performing belonging within a Latina/o diaspora”. Analysis of the maternal and paternal line DNA of Cepeda and several of her family members indicated English or Irish, Berber, and North, West, and Central African, among other heritages. In the absence of autosomal testing, it seems that the Spanish and Native American typical of a “Latina” were not entirely in evidence, but the label applies in any case based on Spanish language, diasporic identity, and Latin American/Caribbean origins. Consequently, the racialization routinely insinuated in genetic ancestry ads becomes even more problematic, as hybridity is depicted not only as a potential disruptor of racialized categories but also as something which, when taking the form of a singular racial grouping, can be legitimized and racialized using ethnic ancestry results.

Continental or subdivided geographic populations in genetic ancestry can, as

Greely (

2008) warns, be easily confused with commonly recognized racial classifications. Consequently, racism emerges in discourses that employ genetic science as a shield.

Pappas (

2011) reports assertions that King Tutankhamen’s Y-DNA had been extracted from his mummified remains and found to reflect European genetics. It was contended that a Discovery Channel program dealing with Tut’s DNA had inadvertently revealed these results, a claim which was then denied by the network. After a European testing provider began touting the potential of shared ancestry with the Egyptian pharaoh in advertising on its website, white supremacists followed by using genetic ancestry science in order to bolster their argument that it was actually Europeans, not Africans, who built the civilization of ancient Egypt (see

Scodari 2015). Whether or not the Y-DNA results were shown, of course, Y-DNA represents only one of an individual’s innumerable ancestral lines, and cannot possibly prove the dominance of a particular racial heritage in the genome of an individual.

It is crucial to ask whether representations and realizations of racial/ethnic hybridity associated with genetic genealogy truly challenge racialization or racism with counter-hegemonic effects. I have described how Harvard literature professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. acknowledges results from conventional genealogy signaling Irish ancestry on his paternal line on the celebrity profile genealogy series

African American Lives 2 (PBS, 2008) (see

Scodari 2015). In Ireland, inspection of his Y-DNA test results ratifies his descent from the infamous warlord King Niall of the Nine Hostages, something that he, an African American, shares with many Irishmen. The Ireland sequence goes on to feature Gates’s interactions with his newfound clan reflecting puzzlement, amusement, and ultimately acceptance. The narrative suggests that hybridity revealed via DNA can, under the right conditions, expand horizons. However, oppressive cultural contexts, such as the historical reality of slave rape that likely produced the Irishness evidenced in Gates’ Y-DNA, and which might summon hegemonic meanings for people inside and outside of Ireland, is absent from the segment.

Resistance, as used in this essay, derives from cultural studies scholar Stuart

Hall’s (

2006) encoding/decoding model. Hall theorized three positions one can take when reading a text. The dominant/preferred reading involves interpreting the text as creators intend, and typically in line with the dominant, hegemonic ideology. The negotiated reading allows for interpretations that preserve the text’s hegemonic essence, but quibble with other details. Finally, the oppositional reading recognizes the hegemonic intent of the text but re-appropriates it for resistive, counter-hegemonic ends. Since this analysis does not gauge audience response, this model is applied in this case by discerning positions likely to be taken by the target audience and the openness of the text to reinterpretation and resistive understandings. Using this theoretical and conceptual framework for analyzing genetic genealogy advertising along with its associated issues, the analysis proceeds by issue category, allowing that individual ads can speak to more than one.

3. Genetics vs. Culture

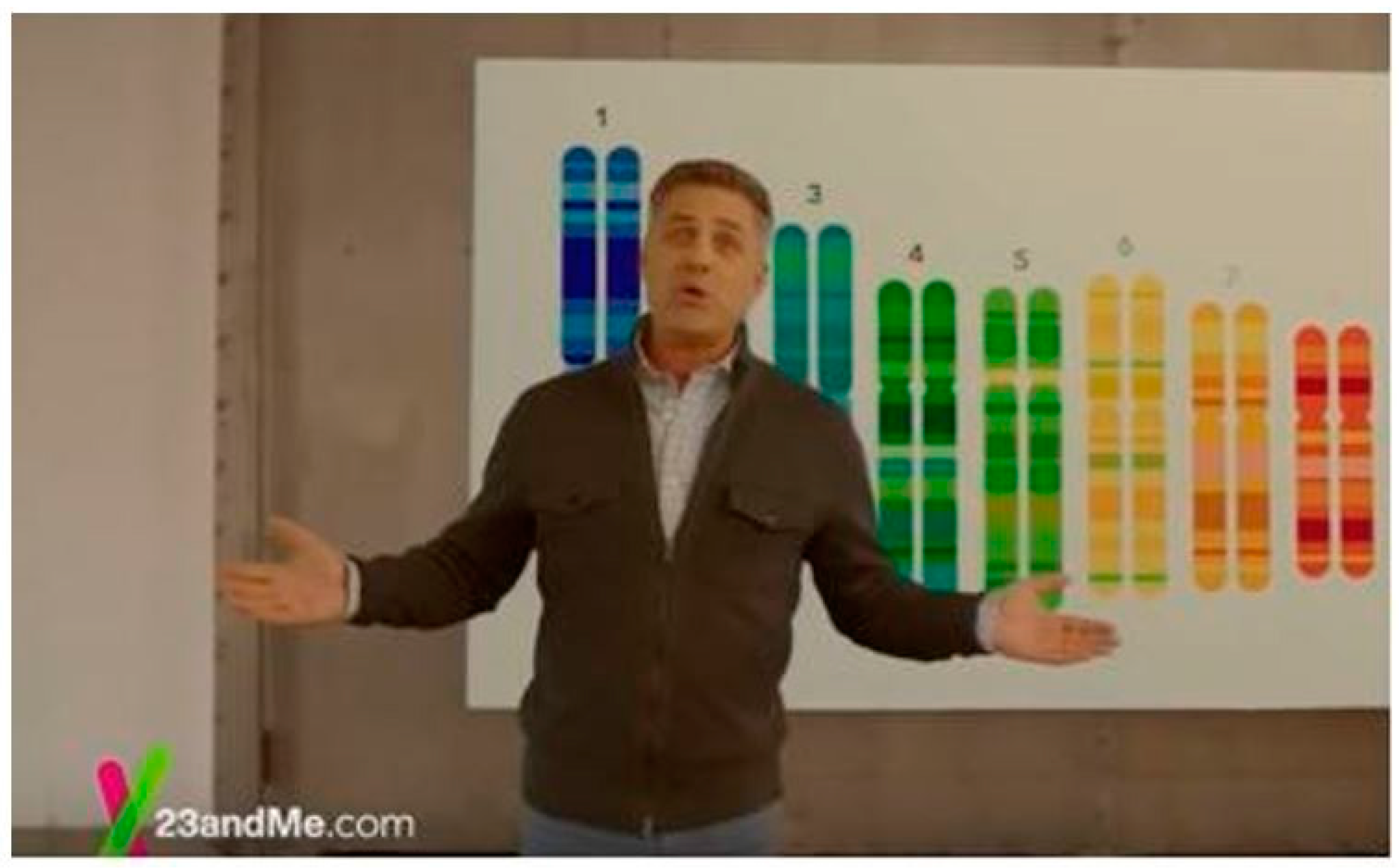

Both conventional and genetic genealogy pivot on the supposition that biological kinship takes precedence over alternative forms of relatedness. However, the inclination to participate in genetic ancestry testing exposes a more absolute postulation—that one’s genome is the primary determinant of one’s identity. This is epitomized in the 23andMe spot entitled “Reinventing Ancestry” (

Figure 1), which contrasts genetic ancestry testing with old-fashioned genealogy. Its tagline, “23 chromosomes that make you who you are,” argues that although biological connection is understood to be transcendent in either circumstance, a scientific seal of approval—a “reinvention”—is at once essential and essentializing. So-called ethnic ancestry result categories are consequently racialized and rendered as unassailable.

In the present context, the preeminence of biological kinship is mother’s milk in the marketing of genetic ancestry testing. Both AncestryDNA and 23andMe feature ads that are not only premised on this idea, but add a narrative pitch that accentuates it. In 2017, 23andMe teamed up with Universal Pictures to cross-promote the testing service along with the computer-animated film

Despicable Me 3, directed by Pierre Coffin and Kyle Balda. In “Gru’s Genetic Journey,” the character of Gru, a reformed villain voiced by Steve Carell, is matched with a long lost twin brother through DNA testing, playing off a plot line in the film. Using a real-life analog, the 23andMe commercial entitled “Siblings: Mandy and Jason’s 23andMe Story” (

Figure 2) depicts the union of half siblings forged through genetic genealogy. A third 23andMe ad, “Adopted,” focuses not on the authenticity of adoptive families, but on an adopted woman’s 40-year search for her biological kin and how DNA testing facilitated her journey. Along with reality television programs such as

Long Lost Family (TLC, 2016–) that these ads often accompany, the last three spots suggest that genetic genealogy providers are carving out a target market of adoptees and others seeking to determine otherwise unknown biological connections through genetic matching.

A related quest is featured in AncestryDNA’s “Learn about You” advertisement celebrating its 69 dollar sale during the summer of 2017. Family history tourism—in this case, to England—is highlighted in a demonstration of how DNA testing can spawn other genealogy-related, family undertakings. “See how a place and its people are all a part of you” the voiceover beckons, again stressing genetic kinship but without encouraging deeper learning that might reveal hybridity within that ancestry as well as cultural tensions and struggles. As

Nash (

2002, p. 47) notes, such travel “can be used to rework the nation as hybrid and heterogeneous”. However, these possibilities do not align with the advertisement’s focus on a single nation out of four seen in the family’s DNA breakdown and imagery that fails to disrupt stereotypical notions of homogeneity within English culture.

4. Hybridity and Fetishization

The notion that “you are your genes” is echoed in many genetic genealogy ads, some of which illustrate more than one major theme. Many of the ads highlighting genetic hybridity also assert the preeminence of genetics in establishing identity. The AncestryDNA ad entitled “Testimonial: Kyle,” in which a man who believed himself to be of mostly German heritage and regularly participated in a dance troupe wearing lederhosen abruptly sheds his German enculturation and dons a Scottish kilt after his ethnic ancestry results indicate his “true” origins (see

Scodari 2015). In terms of the issue at hand, it can also be noted that the lederhosen and the kilt, both of which Kyle is seen wearing, as well as the German-style beer steins propped on a table become fetishized objects signifying, while not elucidating, cultures. In similar fashion, the AncestryDNA ad “Testimonial: Kim” displays the artifacts of indigenous Americans as Kim describes how she learned of her Native American roots. “I wanted to know who I am,” Kim declares, equating genetics and identity and, as an afterthought to the implied acquisition of the items, vowing to explore her heritage beyond the bounds of these fetishized objects.

In the “Katherine and Eric” AncestryDNA ad, Eric provides two Italian family names before Katherine admits that although she thought she married an Italian, Eric actually has a predominantly Eastern European background. Interestingly, Eric’s last name, as given on the iSpotTV.com website hosting the ad, is decidedly more Eastern European than Italian, prompting skepticism concerning why the Italian background had been assumed—a skepticism that might dovetail with other questions about the authenticity of ostensibly “real person” testimonials. Of course, most viewers will not know his name, and will likely dwell on his Italian appearance. A picture of what appears to be Venice is displayed in the spot, seeming to fetishize the Italian affinity Eric once asserted but now appears to have discarded.

The celebration and/or acceptance of hybridity without complexity is the order of the day in AncestryDNA’s “Happy Father’s Day” ad (

Figure 3), as children with Irish accents outfitted in green school uniforms recite or learn of their fathers’ genetic genealogy results. One father hears entirely expected news of his Irishness. Another receives corroboration of British ancestry that is apparently more than anticipated. A third is surprised to learn of Native American origins. A fourth, who appears to have at least some African roots, reads off several European components on his report. The hybridity of two out of three fathers is not explicitly established, but the upshot of the ad is still about hybridity fetishized in the obligatory pie graph, which in this case depicts ethnicity percentages totaling 100 percent that are collectively represented by these men as if they all emanate from a single individual.

The subject of the AncestryDNA ad “Testimonial: Lezlie” (

Figure 4) announces that “What are you?” was the repeatedly posed query that spurred Lezlie to genetically explore her ethnic ancestry. It also implies that genetics and identity are one in the same. From an American perspective, Lezlie appears Black, but is alleged by the results to also be European and Asian. A family photo collage shows her with lighter- and darker-skinned family members who suggest her varied, yet fetishized and culturally decontextualized origins. The photos, however, add an authenticating exclamation point to the pie graph attesting to Lezlie’s hybridity. Annette

Kuhn’s (

2002) concept of collective imagination frames an approach to critically deconstructing family photos so as to bring needed critical context to the meanings that such artifacts, with or without DNA results, cannot. Critical genealogy requires more effort than attending to thirty seconds of television and a snapshot or two entails.

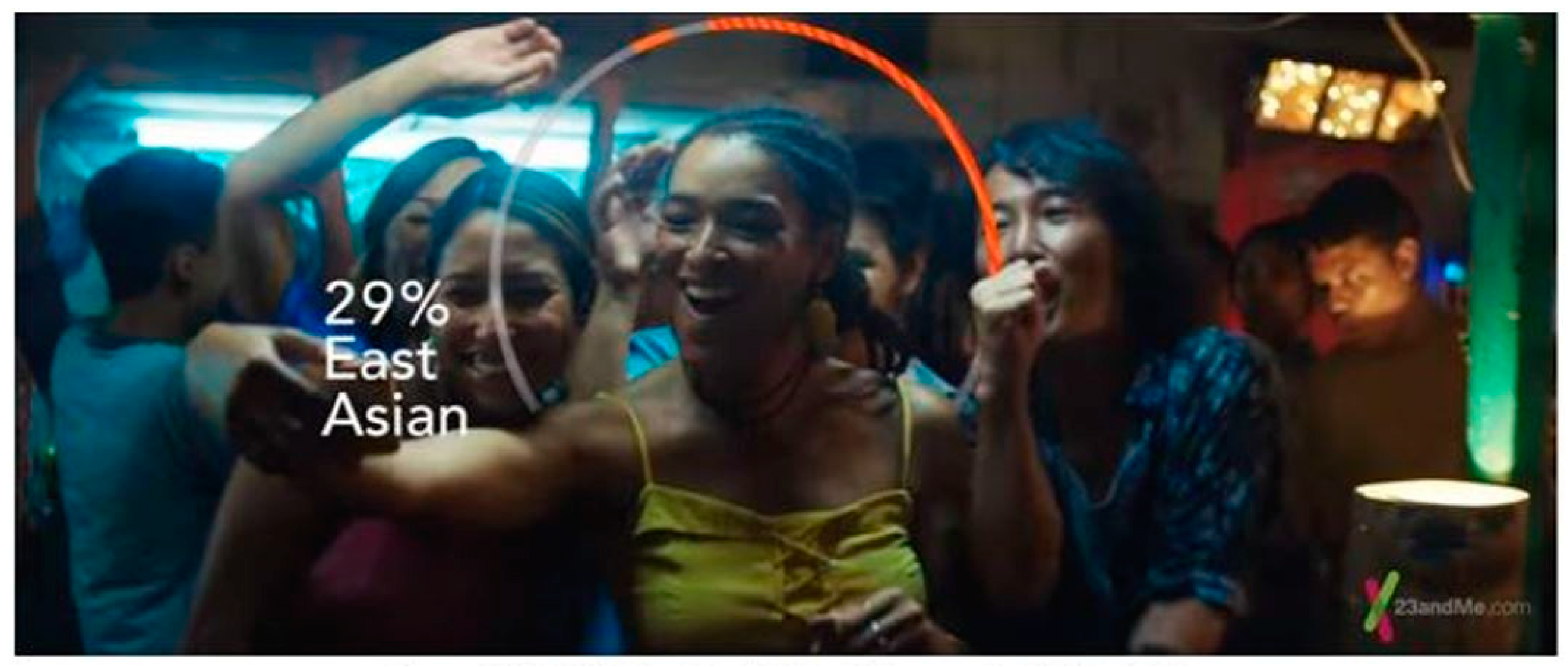

Perhaps no recent ad is more evocative of hybridity in genetic ancestry as 23andMe’s 60-s contest promotional “100% Nicole: The Golden 23 Sweepstakes” (

Figure 5). Answering the entreaty “Follow your DNA around the world,” Nicole, with a facial structure that vaguely reads as Asian, hair color, texture, and style that appear African, freckles that are most common and noticeable on European faces, and a skin color that blends these heritages, ethnographically travels from venue to venue represented in her pie graph accompanied by the song “Getting to Know You” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical

The King and I. In addition to the implication that all the indicated cultures

are her, racial and cultural fetishes continue to be generated as she participates in activities such as soccer and dancing in Africa, sauna and massage in Scandinavia, motor biking betwixt rice paddies in Asia, selfie-taking and imbibing with newly met pals at an Asian watering hole, and dune buggying in the Middle Eastern desert. While the 29% East Asian, 12% Middle Eastern, 46% West African, and 3% Scandinavian results displayed in this version of the spot do not add up to 100%, images of Nicole paddle boarding with native people in what appears to be the Pacific Islands might help the viewer fill in the remaining 10%.

The commercial packaging of mixed ancestry in this advertisement and other genetic genealogy promotions demonstrate the impetus behind

Valdivia’s (

2011, p. 54) call to critically investigate cultural hybridity rather than routinely lauding it “as commodity culture urges us to do”. Like Eve, the computer-generated representative of a multiracial future on the

Time Magazine cover (18 November 1993), Nicole reflects marketing strategies exploiting racial hybridity that stand to divert critical scrutiny away from the complications of fetishized cultures, racism, and racialization as they truly operate in genetic genealogy marketing.

6. Resistance

Autosomal DNA testing for genetic ancestry might create an empowering interpretive occasion to the descendants of African slaves, despite the commodification of these consumers and exploitation of histories of oppression that denied them access to their heritage in the first place. As

Nash (

2007, p. 97) writes: “Many arguments for the value of…geneticised genealogy not only claim that they undermine race, but utilize the histories of violence, enslavement, and cultural dislocation to promote their potential to offer lost knowledge of origins and to make connections”. This anticipates a situation in which resistive prospects are muted by commercial exploitation that is part and parcel of providers’ advertising and cross-marketing strategies.

Nonetheless, creating ads that evoke, without explicitly mentioning, the very context that is strategically ignored in “Declaration Descendants” allows these descendants to pinpoint places and ethnicities that are infrequently determined through conventional genealogy as it probes beyond the historical “brick wall” of slavery.

Mountain and Guelke (

2008) also tout the “subversive potential” of genetic ancestry based on the case in which DNA testing vindicated a group of African Americans claiming descent from Thomas Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings. These examples anticipate resistive potential in the form of oppositional stances and/or readings on the part of or in behalf of slave descendants.

In the AncestryDNA commercial “Lyn Discovers her Ethnicity” (

Figure 8), a Black woman seeks to isolate her ethnicity within Africa through genetic genealogy testing, a proposition that often depends on the size and variety of samples drawn from comparison populations. The term “ethnicity” is used purposefully in the ad, as the resulting pie graph identifies the ethnicities associated with the various African segments but leaves two additional, presumably non-African pie slices blank. Nigerian is Lyn’s largest percentage, prompting her to acquire a Nigerian head wrap or

gele and commit to studying this culture. The ad interpellates descendants of African slaves yearning to break through historical roadblocks in order to make localized connections to Africa. In this light, the

gele functions as more than a fetish as its significance mushrooms in accordance with the injustice of regimes that kept Lyn, and so many others, from being able to claim it as a signifier of their heritage. The narrative’s clear acknowledgment of diversity within African identity can also be read as resistive. As Lyn asserts, it may be “only a hat,” but it is “the most important hat I’ve ever owned.”

Clearly, test takers such as Lyn can attain a sense of resistance by identifying local connections to Africa through genetic genealogy testing, defying the indignity that the loss of cultural identity due to enslavement has inflicted. Whether this counts as an oppositional reading is the pivotal question, since creators fully embrace and anticipate it. This could render it a preferred reading under

Hall’s (

2006) encoding/decoding scheme. Yet it is not a dominant, hegemonic position because of its resistive prospects. What is dominant and hegemonic is the commercial exploitation of this history (see

Nash 2007), and what

Schramm (

2012) identifies as the imprecision, mostly on account of inadequate testing within the comparison populations in Africa, of genetic ancestry results for slave descendant consumers. This concern emerged soon after the debut of these protocols, as providers rode a groundswell of favorable publicity provoked by the PBS genealogy profile television series

African American Lives (2006) and

African American Lives 2 (2008) that featured this particular brand of genetic ancestry testing. Schramm also questions the cross-marketed commodification of these patrons, who are encouraged to extend their quest for African connections with packaged travel experiences that could be correspondently imprecise, long on fetishized imagery, and short on context. Widespread, finely tuned testing stands to ameliorate some of these worries, although the issues of culturally constructed categories and absence of external peer review remain as troubling with respect to these consumers as they are to others.

7. Conclusions

The study has addressed several pivotal questions. First, do the U.S. television ads of genetic ancestry providers emphasize biological kinship to the detriment of cultural inheritance? Second, does the preeminence of hybridity in the ads destabilize racial essentialism? Third, are the ethnicities forming hybrid ancestry culturally or historically contextualized, or are they fetishized? Fourth, are racism and racialization facilitated or hindered by images and narratives in the ads? And, finally, is resistance to racial hegemony mobilized by these texts?

The theoretical framework and analysis demonstrate that the underlying premise for genetic ancestry marketing based on this array of ads is the significance of biological kinship. Stated differently, the biological imperative anchors the commercial imperative. Other definitions of family simply do not enter into the equation unless adoption appears in the ads as a state that must be transcended by newfound biological connection.

Within the context of the American multi-culture, hybridity is also commodified, as autosomal testing is specifically designed to capitalize on consumers’ curiosity about the components of their background. Such curiosity does not necessarily spell commitment to understanding the conditions and struggles inflecting various cultural heritages and, consequently, fetishization creeps in as shorthand.

Moreover, in these spots, ethnically associated objects, artifacts, and practices become receptacles for superficial cultural meanings. In utilizing “ethnic ancestry” and similar terminology, constructing ancestry classifications consistent with culturally constituted racial categories, basing their entire enterprise on unquestioned assumptions of ethnicity and race as essential and decipherable from an individual’s DNA, and neglecting to curtail misconceptions and misuses, genetic ancestry firms are complicit not only in the processes of racialization but in racist misappropriations of genetic science.

The opportunity to resist comes in the form of ads celebrating genetic genealogy’s ability to link the descendants of African slaves to places and peoples in Africa, something not usually possible through conventional genealogical means. However, this targeting and representation still signals the commercial exploitation of historical malfeasance against this group. The need to define one’s ethnic identity through something more specific than a continental designation is, however, palpable in American culture.

Heuristic trajectories for further study can be derived from the findings of this analysis of advertising content based on the four key categories. Three recent cases demonstrate that exploring audience/participant negotiations pertaining to the culture vs. genetics binary is crucial to determining the effectiveness of and the degree and nature of meaning negotiation in regard to genetic genealogy advertising. The first case, a sociological study by

Panofsky and Donovan (

2017) of users on a white nationalist website establishes that these participants, while normally insisting upon the biological validity of racial categories as inscribed in DNA, were willing to question genetic genealogy science if it revealed in them a deficit of racial “purity” (see

Paul 2017).

Second, a pop star known to identify as Latina, Demi Lovato, is excoriated on social media for punctuating her revelations of genetic genealogy results with a final remark that her test also indicated that she is “1% African” (see

Orenstein 2017). Some criticized her for supposedly claiming Black identity based on this data point, while others quarreled with its positioning as an afterthought.

A third case derives from an academic controversy concerning an essay authored by Rebecca

Tuvel (

2017) published in the feminist philosophy journal

Hypatia. In her article, “In Defense of Transracialism,” Tuvel, a white junior scholar in philosophy, compares the rationale behind the claims and circumstances of Rachel Dolezal, an American woman who misrepresented herself as Black, to the logic underlying transgender identity. In rebuttal, many trans people, people of color, and allies cried foul. Among other things, the absence of ancestry from the consideration of what determines racial identity was identified by philosopher Tina Fernandes Botts as a crippling flaw in Tuvel’s argument (see

McKenzie et al. 2017). However, in a discussion following an article defending Tuvel (

Walters 2017), a commenter wondered: “[I]f Rachel Dolezal discovered a ‘drop’ of African ancestry, would she be hailed as a hero?”

Perhaps the answers to this query would resemble those received by Demi Lovato in rejoinder to her announcement of 1% African genetic ancestry. In negotiating genetics vs., culture, for example, where does the notion of “ancestry” fit in? Most would probably answer that it refers to biology, but consider the following response on social media to the use of genetic testing on a U.S. television show featuring African-American celebrities:

I don’t think I would want to know, because, I feel that whatever “percentage” is white or whatever is irrelevant—I am Black because of a culture and a common struggle of my ancestors. I can look around my family and see the yellow and redbone, the noses and the eye colors to tell me that it wasn’t a direct trip from Ile de Goree. I don’t need a DNA test to tell me that.

Here, “culture” and “ancestors” are intertwined and not a binary. Does the reaction to Lovato pivot on whether she is presuming African genetics, African culture, or both? Would the controversy surrounding Rachel Dolezal still exist even if she were found to have a genetic affinity with Africans?

These cases demonstrate how perspectives concerning genetics vs. culture in establishing identity are contingent upon particular circumstances, conveniences, and subjectivities. Genetic genealogy firms present no such equivocation in their ads, as hyping genetics over culture is consistent with their commercial imperatives. However, determining how everyday people in everyday life make sense of these issues and relevant media and messages in the context of genealogy requires additional examination through an ethnographic lens.

Similar methods might clarify understandings related to hybridity and fetishization, racism and racialization, and resistance. They could be mobilized to examine YouTube videos or other social media pronouncements in which genetic genealogy subjects negotiate unexpected hybridity in their results, perhaps revealing racism, resistance, or something in between in their narratives. Similarly, one might investigate rejoinders to YouTube videos such as those arguing that King Tut’s alleged Y-DNA test result supports white supremacy, or to those that use genetic ancestry science to racialize southern European populations as not being “white” (see

Scodari 2015) or respond to them by defending the whiteness of the population in question, thereby reproducing the premise of white superiority.

Continuing exploration of genetic genealogy marketing texts within a variety of cultural contexts and institutional investigation from a political economic perspective of testing providers and their cross-marketing strategies involving media producers that unearth incentives to create potentially problematic content are also warranted. Multi-perspectival avenues of inquiry accounting for production, text, and audience dimensions promise to yield intricate outcomes which, in turn, reveal new issues with which those interested in genetic genealogy are destined to grapple.