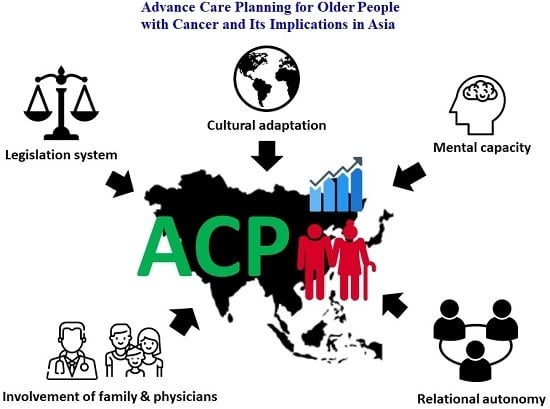

Advance Care Planning for Older People with Cancer and Its Implications in Asia: Highlighting the Mental Capacity and Relational Autonomy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Current development and research work on ACP among older people with cancer in the world

- The benefit of ACP for older people with cancer

- The challenges and implications when promoting ACP in Asia

- The recommendations for further clinical practice, research and policy convictions

2. Development of ACP

2.1. Definition and Meaning of ACP

2.2. Development and Legislation of ACP in the World

2.3. General Introduction of Current Research on ACP in the World

3. Impact of ACP for Older People with Cancer

3.1. Facilitators and Barriers for ACP among Patients with Cancer or Older Adults

3.2. Mental Capacity as a Special Concern in ACP for Older People with Cancer

3.2.1. Meaning of Mental Capacity and Principles to Protect a Person’s Right on Decision Making

- A person must be assumed to have mental capacity unless he or she is proven to lack capacity.

- A person should not be considered as unable to make a decision unless all possible methods have been used without success.

- A person should not be considered as unable to make a decision only because he or she made an unwise decision.

- A decision made on a person’s behalf, who lacks capacity, should be in his or her best interest.

- This act should be applied in a less restrictive manner of a person’s rights and freedom of action.

3.2.2. ACP for People with Potentially Deteriorating or Fluctuating Mental Capacity

3.2.3. How Should Capacity Be Assessed?

4. Challenges of Promoting and Implementing ACP in Asia: Taiwan and Singapore as Examples

4.1. Cultural Adaptation for the Concept of ACP and EOL Discussion

4.2. Involvement of Families and Physicians in ACP Is Crucial

4.3. Relational Autonomy as a Practical Approach in Asia

4.4. Different Legislation Underpinning ACP in Asia

5. Recommendation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Aging and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–260. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Health and Aging; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Cancer Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Weathers, E.; O’Caoimh, R.; Cornally, N.; Fitzgerald, C.; Kearns, T.; Coffey, A.; Daly, E.; O’Sullivan, R.; McGlade, C.; Molloy, D.W. Advance Care Planning: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials Conducted with Older Adults. Maturitas 2016, 91, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.S.; Hayes, B.; Gregorevic, K.; Lim, W.K. The Effects of Advance Care Planning Interventions on Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, L.; Dickinson, C.; Rousseau, N.; Beyer, F.; Clark, A.; Hughes, J.; Howel, D.; Exley, C. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Advance Care Planning Interventions for People with Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Age Ageing 2012, 41, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Butow, P.; Kerridge, I.; Tattersall, M. Advance Care Planning for Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of Perceptions and Experiences of Patients, Families, and Healthcare Providers. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dy, S.M.; Kiley, K.B.; Ast, K.; Lupu, D.; Norton, S.A.; McMillan, S.C.; Herr, K.; Rotella, J.D.; Casarett, D.J. Measuring What Matters: Top-Ranked Quality Indicators for Hospice and Palliative Care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudore, R.L.; Lum, H.D.; You, J.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Meier, D.E.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Matlock, D.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Korfage, I.J.; Ritchie, C.S.; et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detering, K.M.; Hancock, A.D.; Reade, M.C.; Silvester, W. The Impact of Advance Care Planning on End of Life Care in Elderly Patients: Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2010, 340, c1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Respecting Patient Choice Program Advance Care Planning. Available online: http://www.respectingpatientchoices.org.au/background/about-us.html (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Romer, A.L.; Hammes, B.J. Communication, Trust, and Making Choices: Advance Care Planning Four Years on. J. Palliat. Med. 2004, 7, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullick, A.; Martin, J.; Sallnow, L. An Introduction to Advance Care Planning in Practice. BMJ 2013, 347, f6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C.; Rogers, A.; Gately, C.; Kennedy, A. Planning for End of Life Care within Lay-Led Chronic Illness Self-Management Training: The Significance of ‘Death Awareness’ and Biographical Context in Participant Accounts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.; Lobo, B. Advance Care Planning in End of Life Care; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Danis, M.; Southerland, L.I.; Garrett, J.M.; Smith, J.L.; Hielema, F.; Pickard, C.G.; Egner, D.M.; Patrick, D.L. A Prospective Study of Advance Directives for Life-Sustaining Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy: Promoting High Quality Care for Adults at the End of Their Life; DH: London, UK, 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136431/End_of_life_strategy.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2017).

- Chancellor, L. Mental Capacity Act 2005-Code of Practice. 2007. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497253/Mental-capacity-act-code-of-practice.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Carter, R.Z.; Detering, K.M.; Silvester, W.; Sutton, E. Advance Care Planning in Australia: What Does the Law Say? Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, S. The Mental Capacity Act (2008): Code of Practice. Singap. Fam. Physician 2009, 35, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Laws and Regulations Databases of the Republic of China Patient Autonomy Act. Available online: http://www.6law.idv.tw/6law/law/%E7%97%85%E4%BA%BA%E8%87%AA%E4%B8%BB%E6%AC%8A%E5%88%A9%E6%B3%95.htm (accessed on 18 August 2017).

- In der Schmitten, J.; Lex, K.; Mellert, C.; Rothärmel, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Marckmann, G. Implementing an Advance Care Planning Program in German Nursing Homes: Results of an Inter-Regionally Controlled Intervention Trial. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014, 111, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Hu, W.Y. Implementing and Promoting Advance Care Planning for Community Older Adults. Hu Li Za Zhi 2016, 63, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.Y.; Pang, S.M. Let Me Talk-an Advance Care Planning Programme for Frail Nursing Home Residents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 3073–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoya, S.; Kizawa, Y.; Maeno, T. Practice and Perceived Importance of Advance Care Planning and Difficulties in Providing Palliative Care in Geriatric Health Service Facilities in Japan: A Nationwide Survey. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2018, 35, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, R.; Chan, S.; Ng, T.W.; Chiam, A.L.; Lim, S. An Exploratory Study of the Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions of Advance Care Planning in Family Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Illness in Singapore. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.W.; Lee, J.E.; Cho, B.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, S.; Yoo, J.H. End-of-Life Communication in Korean Older Adults: With Focus on Advance Care Planning and Advance Directives. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón Lorda, P.; Barrio Cantalejo, I.; García Gutiérrez, J.F.; Tamayo Velázquez, I.; Villegas Portero, R.; Higueras Callejón, C.; Martínez Pecino, F. Interventions for Promoting the Use of Advance Directives for End-of-Life Decisions in Adults (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg, A.; Rietjens, J.A.; van der Heide, A. The Effects of Advance Care Planning on End-of-Life Care: A Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 1000–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, C.M.; Parker, M.H. Advance Care Planning and End of Life Decision Making. Aust. Fam. Physician 2004, 33, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- British Medical Association. Parliamentary Brief: End-of-Life Decisions; House of Commons Estimaes Day Debate; British Medical Association: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, L.L.; Barry, M.J.; Stoeckle, J.D.; Ettelson, L.M.; Emanuel, E.J. Advance Directives for Medical Care—A Case for Greater Use. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Medical Association. Ama Backs Advance Care Planning by Patients. 2006. Available online: www.ama.com.au/print/2429 (accessed on 13 April 2018).

- American Medical Association. Opinion 2.225: Optimal Use of Orders-Not-to-Intervene and Advance Directives. 1998. Available online: www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/Code_of_Med_Eth/opinoion/opinion2225.html (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Zager, B.S.; Yancy, M. A Call to Improve Practice Concerning Cultural Sensitivity in Advance Directives: A Review of the Literature. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2011, 8, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.P.; Evans, C.J.; Koffman, J.; Armes, J.; Murtagh, F.; Harding, R.; The Conceptual Models That Underpin Advance Care Planning for Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Mechanisms of Action: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Prospero 2017:Crd42017067628. Available online: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017067628 (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- O’Caoimh, R.; Cornally, N.; O’Sullivan, R.; Hally, R.; Weathers, E.; Lavan, A.H.; Kearns, T.; Coffey, A.; McGlade, C.; Molloy, D.W. Advance Care Planning within Survivorship Care Plans for Older Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Maturitas 2017, 105, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exley, C.; Allen, D. A Critical Examination of Home Care: End of Life Care as an Illustrative Case. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 2317–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, L.S.; Huang, X.; Hu, W.Y.; O’Connor, M.; Lee, S. Experiences and Perspectives of Older People Regarding Advance Care Planning: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Huang, C.S.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Halilova, K.I.; Pisu, M.; Drentea, P.; Kvale, E.A.; Bevis, K.S.; Butler, T.W.; Partridge, E.E.; et al. Lay Patient Navigators’ Perspectives of Barriers, Facilitators and Training Needs in Initiating Advance Care Planning Conversations with Older Patients with Cancer. J. Palliat. Care 2018, 33, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.; Collerton, J.C.; Jagger, C.; Bond, J.; Barker, S.A.; Edwards, J.; Hughes, J.; Hunt, J.M.; Robinson, L. Engaging the Oldest Old in Research: Lessons from the Newcastle 85+ Study. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiriaev, O.; Chacko, E.; Jurgens, J.D.; Ramages, M.; Malpas, P.; Cheung, G. Should Capacity Assessments Be Performed Routinely Prior to Discussing Advance Care Planning with Older People? Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, T.; Moran, E.; Kuhn, I.; Barclay, S. Do the Elderly Have a Voice? Advance Care Planning Discussions with Frail and Older Individuals: A Systematic Literature Review and Narrative Synthesis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e657–e668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England Dementia Team and End of Life Care Team. My Future Wishes—Advance Care Planning (Acp) for People with Dementia in All Care Settings; NHS England Dementia Team and End of Life Care Team: Redditch, UK, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso, T.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Hill-Fotouhi, C. The Maccat-T: A Clinical Tool to Assess Patients' Capacities to Make Treatment Decisions. Psychiatr. Serv. 1997, 48, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janofsky, J.S.; McCarthy, R.J.; Folstein, M.F. The Hopkins Competency Assessment Test: A Brief Method for Evaluating Patients’ Capacity to Give Informed Consent. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1992, 43, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, M.T.; Neugroschl, J.; Morrison, R.S.; Marin, D.; Siu, A.L. The Development and Piloting of a Capacity Assessment Tool. J. Clin. Ethics 2001, 12, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Etchells, E.; Darzins, P.; Silberfeld, M.; Singer, P.A.; McKenny, J.; Naglie, G.; Katz, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; Molloy, D.W.; Strang, D. Assessment of Patient Capacity to Consent to Treatment. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999, 14, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessums, L.L.; Zembrzuska, H.; Jackson, J.L. Does This Patient Have Medical Decision-Making Capacity? JAMA 2011, 306, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heywood, R. Revisiting Advance Decision Making under the Mental Capacity Act 2005: A Tale of Mixed Messages. Med. Law Rev. 2015, 23, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.T.; Liu, T.W.; Liu, L.N.; Chiu, C.F.; Hsieh, R.K.; Tsai, C.M. Physician-Patient End-of-Life Care Discussions: Correlates and Associations with End-of-Life Care Preferences of Cancer Patients-a Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.Y.; Huang, C.H.; Chiu, T.Y.; Hung, S.H.; Peng, J.K.; Chen, C.Y. Factors That Influence the Participation of Healthcare Professionals in Advance Care Planning for Patients with Terminal Cancer: A Nationwide Survey in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1701–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, L.S. Advance Care Planning in Taiwan. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 89, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.G.; Wang, Y.W. Promoting Advance Care Planning in Taiwan—A Practical Approach to Chinese Culture. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2011, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, K.; Fisher, P.; Goh, J.; Ng, L.; Koh, H.M.; Yap, P. Advance Care Planning in People with Early Cognitive Impairment. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.C.; Chang, C.J.; Fan, S.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Chang, S.C.; Sung, H.C. Development of an Advance Care Planning Booklet in Taiwan. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2015, 27, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Hu, W.Y.; Chiu, T.Y.; Chen, C.Y. The Practicalities of Terminally Ill Patients Signing Their Own Dnr Orders—A Study in Taiwan. J. Med. Ethics 2008, 34, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, S.; Kars, M.; Malhotra, C.; Campbell, A.V.; van Delden, J.J.M. Advance Care Planning in a Multi-Cultural Family-Centric Community: A Qualitative Study of Healthcare Professionals’, Patients’ and Caregivers’ Perspectives. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, Y.S.; Huang, H.L. The Attitude toward Truth Telling of Cancer in Taiwan. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, D.F. The Bioethical Principles and Confucius’ Moral Philosophy. J. Med. Ethics 2005, 31, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koay, K.; Schofield, P.; Jefford, M. Importance of Health Literacy in Oncology. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 8, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christman, J. Relational Autonomy, Liberal Individualism, and the Social Constitution of Selves. Philos. Stud. Int. J. Philos. Anal. Tradit. 2004, 117, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, E.S.; Kelly, S.E.; Lucivero, F.; Machirori, M.; Dheensa, S.; Prainsack, B. Beyond Individualism: Is There a Place for Relational Autonomy in Clinical Practice and Research? Clin. Ethics 2017, 12, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.I. Law and Autonomy: Reflections on What Role Should and Could the Law Play in Bioethics? In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference Bioethics, Medical Ethics and Health Law, Limassol, Cyprus, 21–23 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-P.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Chen, P.-J. Advance Care Planning for Older People with Cancer and Its Implications in Asia: Highlighting the Mental Capacity and Relational Autonomy. Geriatrics 2018, 3, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3030043

Lin C-P, Cheng S-Y, Chen P-J. Advance Care Planning for Older People with Cancer and Its Implications in Asia: Highlighting the Mental Capacity and Relational Autonomy. Geriatrics. 2018; 3(3):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3030043

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Cheng-Pei, Shao-Yi Cheng, and Ping-Jen Chen. 2018. "Advance Care Planning for Older People with Cancer and Its Implications in Asia: Highlighting the Mental Capacity and Relational Autonomy" Geriatrics 3, no. 3: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3030043