A Full Diagnostic Process for the Orthodontic Treatment Strategy: A Documented Case Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Report

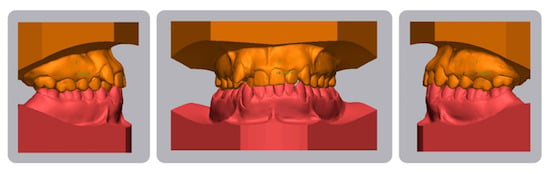

2.1. Diagnosis and Etiology

2.2. Treatment Objectives

2.3. Treatment Alternatives

2.4. Treatment Progress

2.5. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Angle, E.H. Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth and Fractures of the Maxillae: Angle’s System, 6th ed.; S.S. White Dental Manufacturing Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, P.R. Stone age man’s dentition. Am. J. Orthod. 1954, 40, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, C.H. Indications for the extraction of teeth in orthodontic procedure. Am. J. Orthod. Oral Surg. 1944, 42, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetlin, N.M.; Ten Hoeve, A. Nonextraction treatment. J. Clin. Orthod. 1983, 17, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larsson, P.; Bondemark, L.; Häggman-Henrikson, B. The Impact of Orofacial Appearance on Oral Health Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Almeida, N.V.; Silveira, G.S.; Pereira, D.M.; Mattos, C.T.; Mucha, J.N. Interproximal wear versus incisors extraction to solve anterior lower crowding: A systematic review. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2015, 20, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Baek, S.H. Change in maxillary incisor inclination during surgical-orthodontic treatment of skeletal Class III malocclusion: Comparison of extraction and nonextraction of the maxillary first premolars. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.T.; Shaikh, A.; Fida, M. Improvement in Peer Assessment Rating scores after nonextraction, premolar extraction, and mandibular incisor extraction treatments in patients with Class I malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, A.B.; Araujo, E.; Vaden, J.L.; Behrents, R.G.; Oliver, D.R. Extraction vs no treatment: Long-term facial profile changes. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 147, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarmand, A.H.; Zafarmand, M.M. Premolar extraction in orthodontics: Does it have any effect on patient’s facial height? J. Int. Soc. Prevent. Communit. Dent. 2015, 5, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kocadereli, I. Changes in soft tissue profile after orthodontic treatment with and without extractions. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2002, 122, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melsen, B.; Allais, D. Factors of importance for the development of dehiscences during labial movement of mandibular incisors: A retrospective study of adult orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2005, 127, 552–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boke, F.; Gazioglu, C.; Akkaya, S.; Akkaya, M. Relationship between orthodontic treatment and gingival health: A retrospective study. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogel, M.S. Borderline malocclusions. Differential diagnosis—specific therapeutics. J. Clin. Orthod. 1971, 5, 306–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Nucera, R.; Matarese, G.; Portelli, M.; Cervino, G.; Lo Giudice, G.; Militi, A.; Caccianiga, G.; Cicciù, M.; Cordasco, G. Analysis of resistance to sliding expressed during first order correction with conventional and self-ligating brackets: An in-vitro study. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 9, 15575–15581. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Giudice, G.; Lo Giudice, A.; Isola, G.; Fabiano, F.; Artemisia, A.; Fabiano, V.; Nucera, R.; Matarese, G. Evaluation of bond strength and detachment interface distribution of different bracket base designs. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2015, 31, 585. [Google Scholar]

- Cordasco, G.; Lo Giudice, A.; Militi, A.; Nucera, R.; Triolo, G.; Matarese, G. In vitro evaluation of resistance to sliding in self-ligating and conventional bracket systems during dental alignment. Korean J. Orthod. 2012, 42, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tecco, S.; Di Iorio, D.; Nucera, R.; Di Bisceglie, B.; Cordasco, G.; Festa, F. Evaluation of the friction of self-ligating and conventional bracket systems. Eur. J. Dent. 2011, 5, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cordasco, G.; Farronato, G.; Festa, F.; Nucera, R.; Parazzoli, E.; Grossi, G.B. In vitro evaluation of the frictional forces between brackets and archwire with three passive self-ligating brackets. Eur. J. Orthod. 2009, 31, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, E.; Matarese, G.; Di Bella, G.; Nucera, R.; Borsellino, C.; Cordasco, G. Load-deflection characteristics of superelastic and thermal nickel-titanium wires. Eur. J. Orthod. 2013, 35, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nucera, R.; Gatto, E.; Borsellino, C.; Aceto, P.; Fabiano, F.; Matarese, G.; Perillo, L.; Cordasco, G. Influence of bracket-slot design on the forces released by superelastic nickel-titanium alignment wires in different deflection configurations. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nucera, R.; Lo Giudice, A.; Matarese, G.; Artemisia, A.; Bramanti, E.; Crupi, P.; Cordasco, G. Analysis of the characteristics of slot design affecting resistance to sliding during active archwire configurations. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caccianiga, G.; Paiusco, A.; Perillo, L.; Nucera, R.; Pinsino, A.; Maddalone, M.; Cordasco, G.; Lo Giudice, A. Does low-level laser therapy enhance the efficiency of orthodontic dental alignment? Results from a randomized pilot study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Nucera, R.; Perillo, L.; Paiusco, A.; Caccianiga, G. Is low-level laser therapy an effective method to alleviate pain induced by active orthodontic alignment archwire? A randomized clinical trial. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2019, 19, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caccianiga, G.; Crestale, C.; Cozzani, M.; Piras, A.; Mutinelli, S.; Lo Giudice, A.; Cordasco, G. Low-level laser therapy and invisible removal aligners. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2016, 30, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caccianiga, G.; Lo Giudice, A.; Paiusco, A.; Portelli, M.; Militi, A.; Baldoni, M.; Nucera, R. Maxillary Orthodontic Expansion Assisted by Unilateral Alveolar Corticotomy and Low-Level Laser Therapy: A Novel Approach for Correction of a Posterior Unilateral Cross-Bite in Adults. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Nucera, R.; Leonardi, R.; Paiusco, A.; Baldoni, M.; Caccianiga, G. A Comparative Assessment of the Efficiency of Orthodontic Treatment with and without Photobiomodulation During Mandibular Decrowding in Young Subjects: A Single-Center, Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erdinc, A.E.; Nanda, R.S.; Işiksal, E. Relapse of anterior crowding in patients treated with extraction and nonextraction of premolars. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 129, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarmand, A.H.; Qamari, A.; Zafarmand, M.M. Mandibular incisor re-crowding: Is it different in extraction and non-extraction cases? Oral Health Dent. Manag. 2014, 13, 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Germeç, D.; Taner, T.U. Effects of extraction and nonextraction therapy with air-rotor stripping on facial esthetics in postadolescent borderline patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, J.K.; Hans, M.G.; Nelson, S.; Powers, M.P. An assessment of extraction versus nonextraction orthodontic treatment using the peer assessment rating (PAR) index. Angle Orthod. 1998, 68, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantonis, D. The impact of extraction vs nonextraction treatment on soft tissue changes in Class I borderline malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2012, 82, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basciftci, F.A.; Usumez, S. Effects of extraction and nonextraction treatment on class I and class II subjects. Angle Orthod. 2003, 73, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghaffar, F.; Fida, M. Effect of extraction of first four premolars on smile aesthetics. Eur. J. Orthod. 2011, 33, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.C.; Wang, Y.C. Effect of nonextraction and extraction orthodontic treatments on smile esthetics for different malocclusions. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, T.; Southard, K.A.; Casko, J.S.; Qian, F.; Southard, T.E. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2005, 127, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahl, T.J.; Witzig, J.W. The Clinical Management of Basic Maxillofacial Orthopedic Appliances; PSG Publishing Co.: Burlington, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gianelly, A.A. Arch width after extraction and nonextraction treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Barbato, E.; Cosentino, L.; Ferraro, C.M.; Leonardi, R. Alveolar bone changes after rapid maxillary expansion with tooth-born appliances: A systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2018, 40, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantonis, D.; Anthopoulou, C.; Makou, M. Extraction decision and identification of treatment predictors in Class I malocclusions. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nucera, R.; Lo Giudice, A.; Rustico, L.; Matarese, G.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Cordasco, G. Effectiveness of orthodontic treatment with functional appliances on maxillary growth in the short term: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 600–611.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunori, M.; Mashita, M.; Kasai, K. Relationship between facial types and tooth and bone characteristics of the mandible obtained by CT scanning. Angle Orthod. 1998, 68, 557–562. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Caccianiga, G.; Crimi, S.; Cavallini, C.; Leonardi, R. Frequency and type of ponticulus posticus in a longitudinal sample of nonorthodontically treated patients: Relationship with gender, age, skeletal maturity, and skeletal malocclusion. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 126, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, R.; Lo Giudice, A.; Bellocchio, M.; Spinuzza, P.; Caprioglio, A.; Cordasco, G. Diagnostic concordance between skeletal cephalometrics, radiograph-based soft-tissue cephalometrics, and photograph-based soft-tissue cephalometrics. Eur. J. Orthod. 2017, 39, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Rustico, L.; Caprioglio, A.; Migliorati, M.; Nucera, R. Evaluation of condylar cortical bone thickness in patient groups with different vertical facial dimensions using cone-beam computed tomography [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 31]. Odontology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lione, R.; Franchi, L.; Noviello, A.; Bollero, P.; Fanucci, E.; Cozza, P. Three-dimensional evaluation of masseter muscle in different vertical facial patterns: A cross-sectional study in growing children. Ultrason Imaging 2013, 35, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Perillo, L.; Migliorati, M.; Matarese, M.; Dalessandri, D.; Grassia, V.; Alibrandi, A.; Matarese, G. The impact of temporomandibular joint arthritis on functional disability and global health in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2019, 41, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Polizzi, A.; Muraglie, S.; Leonardi, R.M.; Lo Giudice, A. Assessment of vitamin C and Antioxidants Profiles in Saliva and Serum in Patients with Periodontitis and Ischemic Heart Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, G.; Ramaglia, L.; Pedullà, E.; Rapisarda, E.; Iorio-Siciliano, V. Association between periodontitis and glycosylated haemoglobin before diabetes onset: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Ramaglia, L.; Cicciù, M.; Matarese, G. Evaluation of the efficacy of celecoxib and ibuprofen on postoperative pain, swelling, and mouth opening after surgical removal of impacted third molars: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Rapisarda, E.; Matarese, G.; Williams, R.C.; Leonardi, R. Association of vitamin d in patients with periodontal and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontal. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Polizzi, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Indelicato, F.; Ferlito, S. Analysis of Endothelin-1 concentrations in individuals with periodontitis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Polizzi, A.; Santonocito, S.; Alibrandi, A.; Ferlito, S. Expression of Salivary and Serum Malondialdehyde and Lipid Profile of Patients with Periodontitis and Coronary Heart Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferrario, V.F.; Marciandi, P.V.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Dellavia, C.; Sforza, C. Neuromuscular evaluation of post-orthodontic stability: An experimental protocol. Int. J. Adult Orthod. Orthognath. Surg. 2002, 17, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Dalessandri, D.; Migliorati, M.; Pedullà, E.; Rapisarda, E. Comparison of Effectiveness of Etoricoxib and Diclofenac on Pain and Perioperative Sequelae After Surgical Avulsion of Mandibular Third Molars: A Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. Clin. J. Pain 2019, 35, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Lo Giudice, A.; Polizzi, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Patini, R.; Ferlito, S. Periodontitis and Tooth Loss Have Negative Systemic Impact on Circulating Progenitor Cell Levels: A Clinical Study. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isola, G.; Anastasi, G.P.; Matarese, G.; Williams, R.C.; Cutroneo, G.; Bracco, P.; Piancino, M.G. Functional and molecular outcomes of the human masticatory muscles. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Currò, M.; Matarese, M.; Ricca, S.; Matarese, G.; Ientile, R.; Kocher, T. Evaluation of salivary and serum ADMA levels in patients with periodontal and cardiovascular disease as subclinical marker of cardiovascular risk. J. Periodontol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, C.; Filetti, V.; Almeida, L.E.; La Rosa, G.R.M.; Leonardi, R.; Grippaudo, C.; Lo Giudice, A. MMP-7 and MMP-9 are overexpressed in the synovial tissue from severe temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Eur. J. Histochem. 2020, 64, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.; Annunziata, A.; Licciardello, V.; Barbato, E. Soft tissue changes following the extraction of premolars in nongrowing patients with bimaxillary protrusion. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.; Loreto, C.; Talic, N.; Caltabiano, R.; Musumeci, G. Immunolocalization of lubricin in the rat periodontal ligament during experimental tooth movement. Acta Histochem. 2012, 114, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Brewer, I.; Leonardi, R.; Roberts, N.; Bagnato, G. Pain threshold and temporomandibular function in systemic sclerosis: Comparison with psoriatic arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, G.; Trovato, F.M.; Loreto, C.; Leonardi, R.; Szychlinska, M.A.; Castorina, S.; Mobasheri, A. Lubricin expression in human osteoarthritic knee meniscus and synovial fluid: A morphological, immunohistochemical and biochemical study. Acta Histochem. 2014, 116, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, R.; Almeida, L.E.; Trevilatto, P.C.; Loreto, C. Occurrence and regional distribution of TRAIL and DR5 on temporomandibular joint discs: Comparison of disc derangement with and without reduction. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2010, 109, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Pedullà, E.; Grassia, V.; Ferlito, S.; Perillo, L.; Rapisarda, E. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Lornoxicam and Flurbiprofen on Management of Pain and Sequelae Following Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled, Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lo Muzio, L.; Campisi, G.; Farina, A.; Rubini, C.; Pastore, L.; Giannone, N.; Colella, G.; Leonardi, R.; Carinci, F. Effect of p63 expression on survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Investig. 2007, 25, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Isola, G.; Rustico, L.; Ronsivalle, V.; Portelli, M.; Nucera, R. The Efficacy of Retention Appliances after Fixed Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piancino, M.G.; Isola, G.; Cannavale, R.; Cutroneo, G.; Vermiglio, G.; Bracco, P.; Anastasi, G.P. From periodontal mechanoreceptors to chewing motor control: A systematic review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 78, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutroneo, G.; Piancino, M.G.; Ramieri, G.; Bracco, P.; Vita, G.; Isola, G.; Vermiglio, G.; Favaloro, A.; Anastasi, G.P.; Trimarchi, F. Expression of muscle-specific integrins in masseter muscle fibers during malocclusion disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavuoti, S.; Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Abdolreza, J.; Femiano, F.; Perillo, L. Combined orthodontic-surgical management of a transmigrated mandibular canine. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matarese, G.; Currò, M.; Isola, G.; Caccamo, D.; Vecchio, M.; Giunta, M.L.; Ramaglia, L.; Cordasco, G.; Williams, R.C.; Ientile, R. Transglutaminase 2 up-regulation is associated with RANKL/OPG pathway in cultured HPDL cells and THP-1-differentiated macrophages. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 2447–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perillo, L.; Isola, G.; Esercizio, D.; Iovane, M.; Triolo, G.; Matarese, G. Differences in craniofacial characteristics in Southern Italian children from Naples: A retrospective study by cephalometric analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2013, 14, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Currò, M.; Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Caccamo, D.; Ventura, V.P.; Cornelius, C.; Lentini, M.; Cordasco, G.; Ientile, R. Differential expression of transglutaminase genes in patients with Chronic Periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Lo Gullo, A.; Bagnato, G.; Cordasco, G.; Perillo, L. Occlusal and MRI characterizations in systemic sclerosis patients: A prospective study from Southern Italian cohort. Jt. Bone Spine 2016, 83, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, R.; Lo Giudice, A.; Rugeri, M.; Muraglie, S.; Cordasco, G.; Barbato, E. Three-dimensional evaluation on digital casts of maxillary palatal size and morphology in patients with functional posterior crossbite. Eur. J. Orthod. 2018, 40, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Fastuca, R.; Portelli, M.; Militi, A.; Bellocchio, M.; Spinuzza, P.; Briguglio, F.; Caprioglio, A.; Nucera, R. Effects of rapid vs slow maxillary expansion on nasal cavity dimensions in growing subjects: A methodological and reproducibility study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Williams, R.C.; Lo Gullo, A.; Ramaglia, L.; Matarese, M.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Cosio, C.; Matarese, G. Risk association between scleroderma disease characteristics, periodontitis, and tooth loss. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 2733–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavale, R.; Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Grassia, V.; Perillo, L. Early treatment of an ectopic premolar to prevent molar-premolar transposition. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarese, G.; Portelli, M.; Mazza, M.; Militi, A.; Nucera, R.; Gatto, E.; Cordasco, G. Evaluation of skin dose in a low dose spiral CT protocol. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2006, 7, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, G.; Cordasco, G.; Rotondo, F.; Crupi, A.; Ramaglia, L. Anticoagulant therapy in patients undergoing dental interventions: A critical review of the literature and current perspectives. Minerva Stomatol. 2015, 64, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Ramaglia, L.; Dalessandri, D.; Lucchese, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Fabiano, F.; Cordasco, G. Periodontal biotype: Characteristic, prevalence and dimensions related to dental malocclusion. Minerva Stomatol. 2016, 65, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Matarese, G.; Isola, G.; Anastasi, G.P.; Cutroneo, G.; Favaloro, A.; Vita, G.; Cordasco, G.; Milardi, D.; Zizzari, V.L.; Tetè, S.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor levels in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2013, 11, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Briguglio, F.; Grassia, V.; Picciolo, G.; Fiorillo, L.; Matarese, G. Effectiveness of Low-Level Laser Therapy during Tooth Movement: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perillo, L.; Padricelli, G.; Isola, G.; Femiano, F.; Chiodini, P.; Matarese, G. Class II malocclusion division 1: A new classification method by cephalometric analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2012, 13, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, M.; Ramaglia, L.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Cordasco, G.; Matarese, G. Efficacy of a drug composed of herbal extracts on postoperative discomfort after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molar: A randomized, triple-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 2443–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprioglio, A.; Bergamini, C.; Franchi, L.; Vercellini, N.; Zecca, P.A.; Nucera, R.; Fastuca, R. Prediction of Class II improvement after rapid maxillary expansion in early mixed dentition. Prog. Orthod. 2017, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo Giudice, A.; Rustico, L.; Ronsivalle, V.; Spinuzza, P.; Polizzi, A.; Bellocchio, A.M.; Scapellato, S.; Portelli, M.; Nucera, R. A Full Diagnostic Process for the Orthodontic Treatment Strategy: A Documented Case Report. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8020041

Lo Giudice A, Rustico L, Ronsivalle V, Spinuzza P, Polizzi A, Bellocchio AM, Scapellato S, Portelli M, Nucera R. A Full Diagnostic Process for the Orthodontic Treatment Strategy: A Documented Case Report. Dentistry Journal. 2020; 8(2):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8020041

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo Giudice, Antonino, Lorenzo Rustico, Vincenzo Ronsivalle, Paola Spinuzza, Alessandro Polizzi, Angela Mirea Bellocchio, Simone Scapellato, Marco Portelli, and Riccardo Nucera. 2020. "A Full Diagnostic Process for the Orthodontic Treatment Strategy: A Documented Case Report" Dentistry Journal 8, no. 2: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj8020041