The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

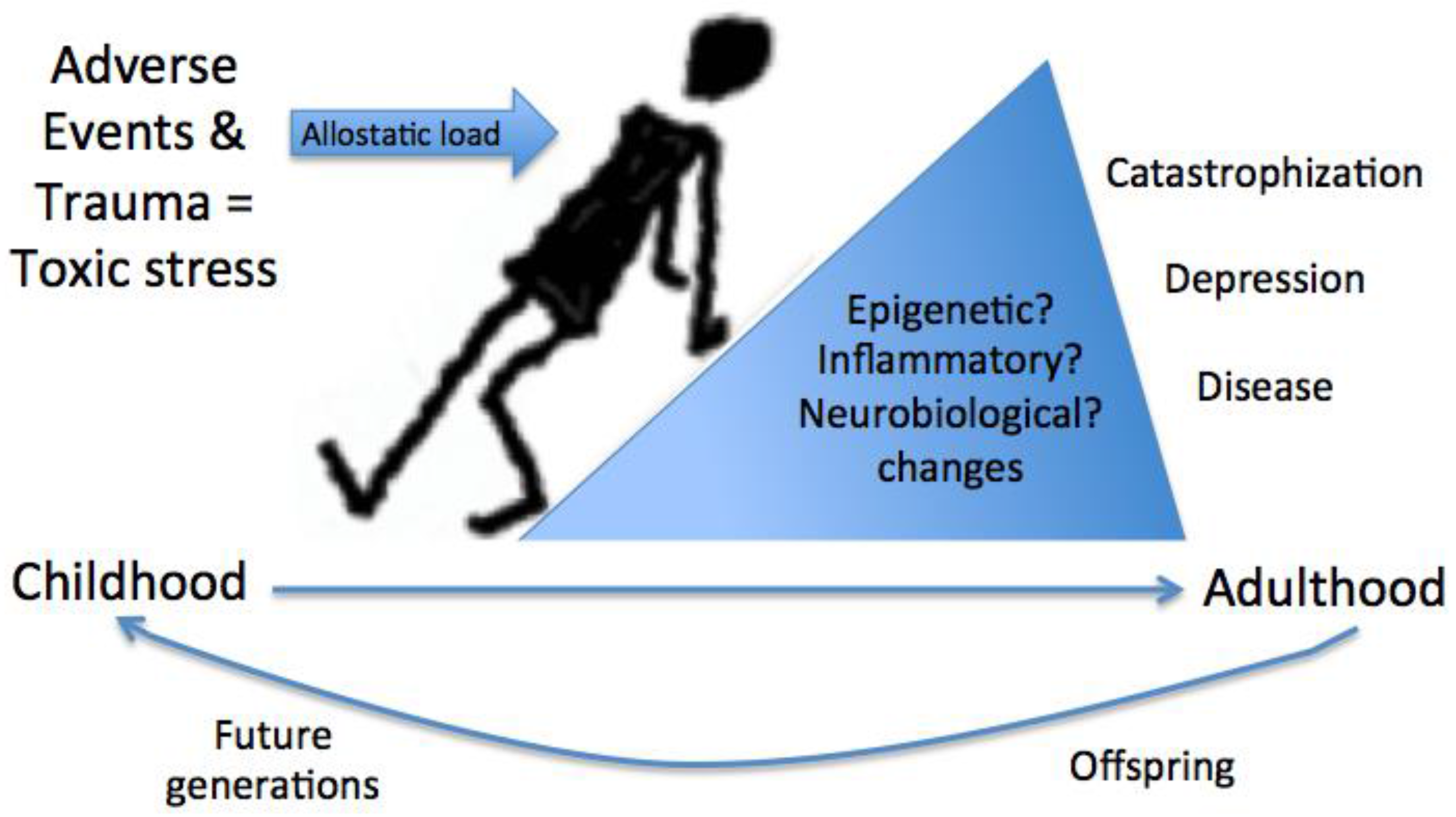

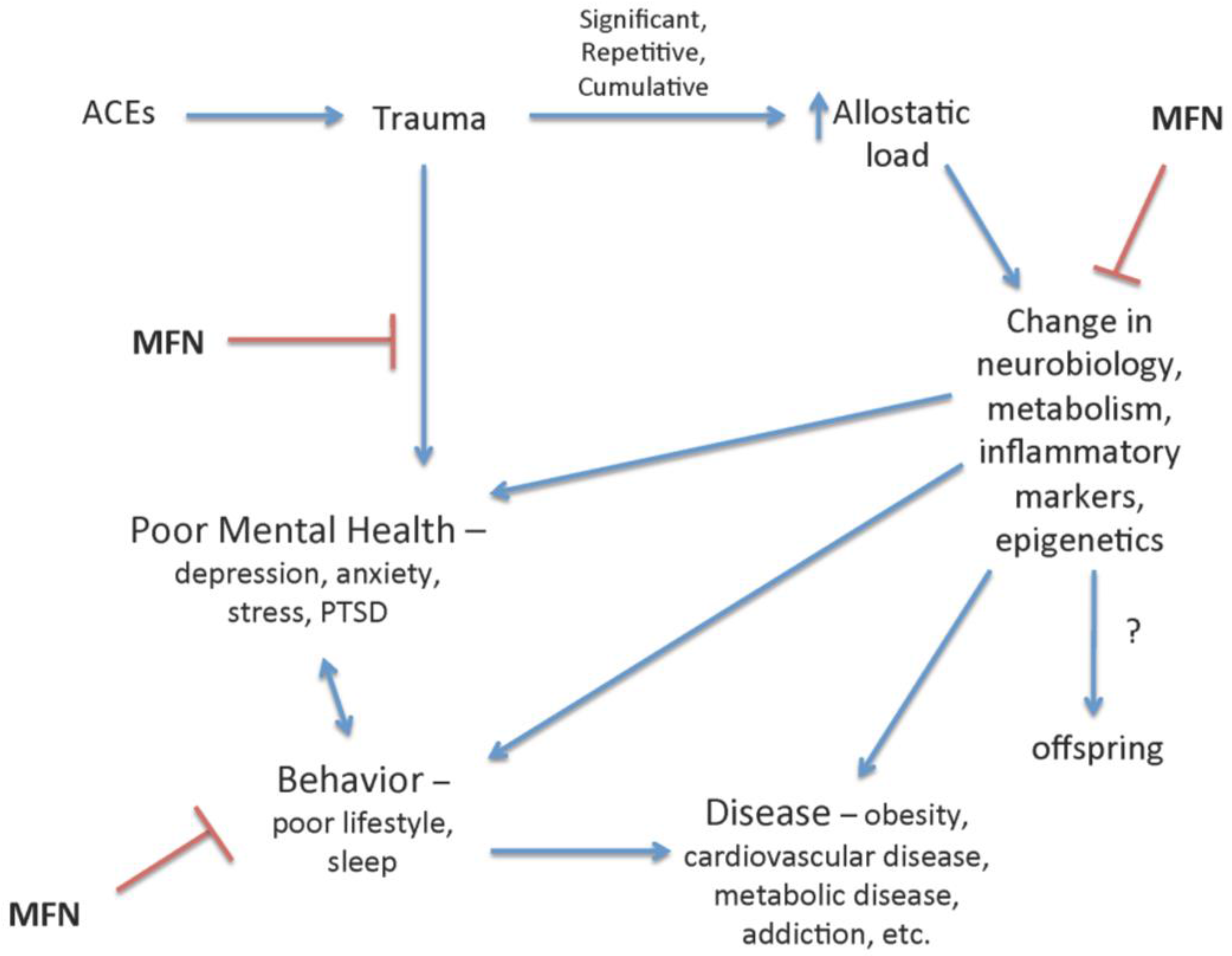

2. ACEs and Trauma

3. Mindfulness

3.1. Mindfulness in Trauma

3.2. Mindfulness in Youth

3.3. Resilience and Mindfulness

4. Mindfulness Program Considerations

4.1. Mindfulness Practice and Instructor Training

4.2. Trauma-Informed Care

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Healty; Committee on Early Childhood Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.B.; Riley, A.W.; Granger, D.A.; Riis, J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, A.; McEwen, B.S. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrenn, G.L.; Wingo, A.P.; Moore, R.; Pelletier, T.; Gutman, A.R.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J. The effect of resilience on posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed inner-city primary care patients. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2011, 103, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.E.; Roberts, S.J.; Chiodo, L. Resilience intervention for young adults with adverse childhood experiences. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2015, 21, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adverse Childhood Experiences Reported by Adults—Five States, 2009; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010; pp. 1609–1613.

- Gonzalez, A.; Monzon, N.; Solis, D.; Jaycox, L.; Langley, A.K. Trauma exposure in elementary school children: Description of screening procedures, level of exposure, and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Sch. Ment. Health 2016, 8, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeda, M.; Oshio, T.; Fujii, M. The impact of the experience of childhood poverty on adult health-risk behaviors in japan: A mediation analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, J.E.; Gruenewald, T.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Matthews, K.A.; Seeman, T.E. Childhood abuse, parental warmth, and adult multisystem biological risk in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17149–17153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, S.L. Psychosocial adjustment of adult children of alcoholics: A review of the recent empirical literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, A.S.; Shonkoff, J.P.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: Translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e224–e231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danese, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Harrington, H.; Milne, B.J.; Polanczyk, G.; Pariante, C.M.; Poulton, R.; Caspi, A. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou, C.A.; van Veldhoven, K.; Relton, C.; Stringhini, S.; Kyriacou, K.; Vineis, P. Biological embedding of early-life exposures and disease risk in humans: A role for DNA methylation. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 45, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, R.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Bierer, L.M.; Bader, H.N.; Klengel, T.; Holsboer, F.; Binder, E.B. Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, A.D.; Boyle, A.E.; Sadler, S. Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Willoughby, M.T.; Garrett-Peters, P.; Wagner, N.; Vernon-Feagans, L.; Family Life Project Key Investigators. The interplay among socioeconomic status, household chaos, and parenting in the prediction of child conduct problems and callous-unemotional behaviors. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potijk, M.R.; Kerstjens, J.M.; Bos, A.F.; Reijneveld, S.A.; de Winter, A.F. Developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children with low socioeconomic status: Risks multiply. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursache, A.; Noble, K.G.; Pediatric Imaging, Neurocognition and Genetics Study. Socioeconomic status, white matter, and executive function in children. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursache, A.; Noble, K.G. Neurocognitive development in socioeconomic context: Multiple mechanisms and implications for measuring socioeconomic status. Psychophysiology 2016, 53, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, A.; Potter, G.G.; McQuoid, D.R.; Boyd, B.; Turner, R.; MacFall, J.R.; Taylor, W.D. Effects of early life stress on depression, cognitive performance and brain morphology. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharoun-Lee, M.; Adair, L.S.; Kaufman, J.S.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Obesity, race/ethnicity and the multiple dimensions of socioeconomic status during the transition to adulthood: A factor analysis approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anda, R.F.; Croft, J.B.; Felitti, V.J.; Nordenberg, D.; Giles, W.H.; Williamson, D.F.; Giovino, G.A. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA 1999, 282, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wang, X.; Pollock, J.S.; Treiber, F.A.; Xu, X.; Snieder, H.; McCall, W.V.; Stefanek, M.; Harshfield, G.A. Adverse childhood experiences and blood pressure trajectories from childhood to young adulthood: The Georgia stress and heart study. Circulation 2015, 131, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Lerner, J.S.; Sage, R.M.; Lehman, B.J.; Seeman, T.E. Early environment, emotions, responses to stress, and health. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1365–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, E.F.; Edwards, E.M.; Heeren, T.; Hingson, R.W. Adverse childhood experiences predict earlier age of drinking onset: Results from a representative us sample of current or former drinkers. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e298–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Rahman, I. Current concepts on the role of inflammation in COPD and lung cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2009, 9, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, G.; Su, S.B. The critical role of toll-like receptor signaling pathways in the induction and progression of autoimmune diseases. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009, 9, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Miranda, A.A.; Salemi, J.L.; King, L.M.; Baldwin, J.A.; Berry, E.L.; Austin, D.A.; Scarborough, K.; Spooner, K.K.; Zoorob, R.J.; Salihu, H.M. Adverse childhood experiences and health-related quality of life in adulthood: Revelations from a community needs assessment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, C.; Cunradi, C.B.; Todd, M. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence: Testing psychosocial mediational pathways among couples. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis, S.D.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Nordenberg, D.; Marchbanks, P.A. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: A retrospective study. Pediatrics 2000, 106, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Baird, S.L.; Dhrodia, R.; Brennenstuhl, S. The association between adverse childhood experiences (ACES) and suicide attempts in a population-based study. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, N.N.; Pettingell, S.L.; McMorris, B.J.; Borowsky, I.W. Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e778–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarupski, K.A.; Parisi, J.M.; Thorpe, R.; Tanner, E.; Gross, D. The association of adverse childhood experiences with mid-life depressive symptoms and quality of life among incarcerated males: Exploring multiple mediation. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, R.; Ballard, E.D.; Machado-Vieira, R.; Saligan, L.N.; Walitt, B. Quantifying the influence of child abuse history on the cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2016, 34, S59–S66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tietjen, G.E.; Khubchandani, J.; Herial, N.A.; Shah, K. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with migraine and vascular biomarkers. Headache 2012, 52, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Videlock, E.J.; Shih, W.; Presson, A.P.; Mayer, E.A.; Chang, L. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal symptom severity. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, K.; Schafer, V.; Schenkel, M.; Nissen, L.; Schwander, J. Adverse childhood experiences associated with sleep in primary insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 2007, 16, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.J.; Thacker, L.R.; Cohen, S.A. Association between adverse childhood experiences and diagnosis of cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poletti, S.; Colombo, C.; Benedetti, F. Adverse childhood experiences worsen cognitive distortion during adult bipolar depression. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1803–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, N.J.; Hellman, J.L.; Scott, B.G.; Weems, C.F.; Carrion, V.G. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillis, S.D.; Anda, R.F.; Dube, S.R.; Felitti, V.J.; Marchbanks, P.A.; Marks, J.S. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Dell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carmody, J.; Baer, R.A. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 31, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006, 13, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batink, T.; Peeters, F.; Geschwind, N.; van Os, J.; Wichers, M. How does MBCT for depression work? Studying cognitive and affective mediation pathways. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, S.; Chawla, N.; Collins, S.E.; Witkiewitz, K.; Hsu, S.; Grow, J.; Clifasefi, S.; Garner, M.; Douglass, A.; Larimer, M.E.; et al. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Subst. Abus. 2009, 30, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallegos, A.M.; Lytle, M.C.; Moynihan, J.A.; Talbot, N.L. Mindfulness-based stress reduction to enhance psychological functioning and improve inflammatory biomarkers in trauma-exposed women: A pilot study. Psychol Trauma 2015, 7, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, E.; Magyari, T.; Langenberg, P.; Chesney, M.; Berman, B. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 66, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Earley, M.D.; Chesney, M.A.; Frye, J.; Greene, P.A.; Berman, B.; Kimbrough, E. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors: A 2.5-year follow-up. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferszt, G.G.; Miller, R.J.; Hickey, J.E.; Maull, F.; Crisp, K. The impact of a mindfulness based program on perceived stress, anxiety, depression and sleep of incarcerated women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 11594–11607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmanowitz, D.L.; Ho, R.T. Art therapy and mindfulness with survivors of political violence: A qualitative study. Psychol. Trauma 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatt, M.; Steinberg, B.; Duchemin, A.M. Mindfulness in motion (MIM): An onsite mindfulness based intervention (MBI) for chronically high stress work environments to increase resiliency and work engagement. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, e52359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.C.; Thom, N.J.; Stanley, E.A.; Haase, L.; Simmons, A.N.; Shih, P.A.; Thompson, W.K.; Potterat, E.G.; Minor, T.R.; Paulus, M.P. Modifying resilience mechanisms in at-risk individuals: A controlled study of mindfulness training in marines preparing for deployment. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polusny, M.A.; Erbes, C.R.; Thuras, P.; Moran, A.; Lamberty, G.J.; Collins, R.C.; Rodman, J.L.; Lim, K.O. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possemato, K.; Bergen-Cico, D.; Treatman, S.; Allen, C.; Wade, M.; Pigeon, W. A randomized clinical trial of primary care brief mindfulness training for veterans with PTSD. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen-Cico, D.; Possemato, K.; Pigeon, W. Reductions in cortisol associated with primary care brief mindfulness program for veterans with PTSD. Med. Care 2014, 52, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bormann, J.E.; Oman, D.; Walter, K.H.; Johnson, B.D. Mindful attention increases and mediates psychological outcomes following mantram repetition practice in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Med. Care 2014, 52, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffner, K.L.; Crean, H.F.; Kemp, J.E. Meditation programs for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Aggregate findings from a multi-site evaluation. Psychol. Trauma 2016, 8, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluepfel, L.; Ward, T.; Yehuda, R.; Dimoulas, E.; Smith, A.; Daly, K. The evaluation of mindfulness-based stress reduction for veterans with mental health conditions. J. Holist Nurs. 2013, 31, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, L.G.; Bui, E.; Baier, A.L.; Mehta, D.H.; Denninger, J.W.; Fricchione, G.L.; Casey, A.; Kagan, L.; Park, E.R.; Simon, N.M. Resilient warrior: A stress management group to improve psychological health in service members. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad Marzabadi, E.; Hashemi Zadeh, S.M. The effectiveness of mindfulness training in improving the quality of life of the war victims with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Iran. J. Psychiatry 2014, 9, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Omidi, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Zargar, F.; Akbari, H. Efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction on mood states of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Arch. Trauma Res. 2013, 1, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, A.; Danoff-Burg, S. Mindfulness as a moderator in expressive writing. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm, K.A.; Meyer, E.C.; Neff, K.D.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Gulliver, S.B.; Morissette, S.B. Mindfulness, self-compassion, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and functional disability in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basharpoor, S.; Shafiei, M.; Daneshvar, S. The comparison of experiential avoidance, [corrected] mindfulness and rumination in trauma-exposed individuals with and without posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in an Iranian sample. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 29, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieleman, K.; Cacciatore, J. Witness to suffering: Mindfulness and compassion fatigue among traumatic bereavement volunteers and professionals. Soc. Work 2014, 59, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M.; et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, C.T.; Segal, D.L.; Coolidge, F.L. Anxiety sensitivity, experiential avoidance, and mindfulness among younger and older adults: Age differences in risk factors for anxiety symptoms. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2015, 81, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.E. “Being mindful”: Does it help adolescents and young adults who have completed cancer treatment? J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 32, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senders, A.; Bourdette, D.; Hanes, D.; Yadav, V.; Shinto, L. Perceived stress in multiple sclerosis: The potential role of mindfulness in health and well-being. J. Evid. Based Complemen. Altern. Med. 2014, 19, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharplin, G.R.; Jones, S.B.; Hancock, B.; Knott, V.E.; Bowden, J.A.; Whitford, H.S. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: An efficacious community-based group intervention for depression and anxiety in a sample of cancer patients. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 193, S79–S82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Locicero, B.; Mahaffey, B.; Fleming, C.; Harris, J.; Vujanovic, A.A. Internalized Hiv stigma and mindfulness: Associations with PTSD symptom severity in trauma-exposed adults with HIV/AIDS. Behav. Modif. 2016, 40, 144–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.S.; Slavich, G.M. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1373, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.D.; Taren, A.A.; Lindsay, E.K.; Greco, C.M.; Gianaros, P.J.; Fairgrieve, A.; Marsland, A.L.; Brown, K.W.; Way, B.M.; Rosen, R.K.; et al. Alterations in resting-state functional connectivity link mindfulness meditation with reduced interleukin-6: A randomized controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaliman, P.; Alvarez-Lopez, M.J.; Cosin-Tomas, M.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 40, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibinga, E.M.; Perry-Parrish, C.; Chung, S.E.; Johnson, S.B.; Smith, M.; Ellen, J.M. School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: A small randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibinga, E.M.; Webb, L.; Ghazarian, S.R.; Ellen, J.M. School-based mindfulness instruction: An RCT. Pediatrics 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jee, S.H.; Couderc, J.P.; Swanson, D.; Gallegos, A.; Hilliard, C.; Blumkin, A.; Cunningham, K.; Heinert, S. A pilot randomized trial teaching mindfulness-based stress reduction to traumatized youth in foster care. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibinga, E.M.; Perry-Parrish, C.; Thorpe, K.; Mika, M.; Ellen, J.M. A small mixed-method RCT of mindfulness instruction for urban youth. Explore 2014, 10, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibinga, E.M.; Stewart, M.; Magyari, T.; Welsh, C.K.; Hutton, N.; Ellen, J.M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for hiv-infected youth: A pilot study. Explore 2008, 4, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyken, W.; Weare, K.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Vicary, R.; Motton, N.; Burnett, R.; Cullen, C.; Hennelly, S.; Huppert, F. Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, W.B.; Lepp, N.E.; Niles, H.F.; Rocha, T.; Fisher, N.E.; Gold, J.S. A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. J. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 52, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Weijer-Bergsma, E.; Formsma, A.R.; de Bruin, E.I.; Bogels, S.M. The effectiveness of mindfulness training on behavioral problems and attentional functioning in adolescents with adhd. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2012, 21, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.S.; O’Reilly, G.A.; Olmstead, R.; Breen, E.C.; Irwin, M.R. Mindfulness meditation and improvement in sleep quality and daytime impairment among older adults with sleep disturbances: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biegel, G.M.; Brown, K.W.; Shapiro, S.L.; Schubert, C.M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, S.; Luong, M.T.; Schmidt, S.; Bauer, J. Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.N.; Lancioni, G.E.; Winton, A.S.W.; Karazsia, B.T.; Singh, J. Mindfulness training for teachers changes the behavior of their preschool students. Res. Human Dev. 2013, 10, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.A.; Frank, J.L.; Snowberg, K.E.; Coccia, M.A.; Greenberg, M.T. Improving classroom learning environments by cultivating awareness and resilience in education (care): Results of a randomized controlled trial. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2013, 28, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.; Gombojav, N.; Solloway, M.; Wissow, L. Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and mindfulness-based approaches: Common denominator issues for children with emotional, mental, or behavioral problems. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townshend, K.; Jordan, Z.; Stephenson, M.; Tsey, K. The effectiveness of mindful parenting programs in promoting parents’ and children’s wellbeing: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 139–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, J.; Clifton, J.; Forehand, R.; Golub, A.; Reid, M.; Pichler, E.R. Parental mindfulness and dyadic relationship quality in low-income cohabiting black stepfamilies: Associations with parenting experienced by adolescents. Couple Fam. Psychol. 2014, 3, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent, J.; McKee, L.G.; J, N.R.; Forehand, R. The association of parent mindfulness with parenting and youth psychopathology across three developmental stages. J. Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016, 44, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawe, S.; Harnett, P. Reducing potential for child abuse among methadone-maintained parents: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2007, 32, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingo, A.P.; Wrenn, G.; Pelletier, T.; Gutman, A.R.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J. Moderating effects of resilience on depression in individuals with a history of childhood abuse or trauma exposure. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingo, A.P.; Fani, N.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J. Psychological resilience and neurocognitive performance in a traumatized community sample. Depress Anxiety 2010, 27, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A. The development and psychometric evaluation of the brief resilient coping scale. Assessment 2004, 11, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.W.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R. Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abus. 2011, 12, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujanovic, A.A.; Youngwirth, N.E.; Johnson, K.A.; Zvolensky, M.J. Mindfulness-based acceptance and posttraumatic stress symptoms among trauma-exposed adults without axis i psychopathology. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry-Parrish, C.; Copeland-Linder, N.; Webb, L.; Sibinga, E.M. Mindfulness-based approaches for children and youth. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2016, 46, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E.L.; Roberts-Lewis, A. Differential roles of thought suppression and dispositional mindfulness in posttraumatic stress symptoms and craving. Addict. Behav. 2013, 38, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1982, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, J.; Baer, R.A. How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mindfulness-Based Professional Education. Available online: http://www.umassmed.edu/cfm/training/ (accesses on 20 December 2016).

- Waelde, L.C.; Thompson, J.M.; Robinson, A.; Iwanicki, S. Trauma therapists’ clinical applications, training, and personal practice of mindfulness and meditation. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelson, T.; Tandon, S.D.; O’Brennan, L.; Leaf, P.J.; Ialongo, N.S. Brief report: Moving prevention into schools: The impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. J. Adolesc. 2015, 43, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiklejohn, J.; Phillips, C.; Freedman, M.L.; Griffin, M.L.; Biegel, G.; Roach, A.; Frank, J.; Burke, C.; Pinger, L.; Soloway, G.; et al. Integrating mindfulness training into k-12 education: Fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness 2012, 3, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindful in Schools Project. Available online: https://mindfulnessinschools.org (accesses on 20 December 2016).

- Mindful Schools. Available online: http://www.mindfulschools.org/ (accesses on 20 December 2016).

- Kemeny, M.E.; Foltz, C.; Cavanagh, J.F.; Cullen, M.; Giese-Davis, J.; Jennings, P.; Rosenberg, E.L.; Gillath, O.; Shaver, P.R.; Wallace, B.A.; et al. Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emotion 2012, 12, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, C.; Manas, I.; Cangas, A.J.; Moreno, E.; Gallego, J. Reducing teachers’ psychological distress through a mindfulness training program. Span. J. Psychol. 2010, 13, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flook, L.; Goldberg, S.B.; Pinger, L.; Bonus, K.; Davidson, R.J. Mindfulness for teachers: A pilot study to assess effects on stress, burnout and teaching efficacy. Mind Brain Educ. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crain, T.L.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Roeser, R.W. Cultivating teacher mindfulness: Effects of a randomized controlled trial on work, home, and sleep outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.; Burke, C.; Brinkman, S.; Wade, T. Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness program for transdiagnostic prevention in young adolescents. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, L.G.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Greenberg, M.T. Pilot study to gauge acceptability of a mindfulness-based, family-focused preventive intervention. J. Prim. Prev. 2009, 30, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.S.; Fernando, R. Mindfulness Training and Classroom Behavior Among Lower-Income and Ethnic Minority Elementary School Children. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himelstein, S.; Saul, S.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Pinedo, D. Mindfulness training as an intervention for substance user incarcerated adolescents: A pilot grounded theory study. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 49, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Wade, T.D. Mindfulness-based prevention for eating disorders: A school-based cluster randomized controlled study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, J.M.; Roake, C.; Sheikh, I.; Mole, A.; Nigg, J.T.; Oken, B. School-based mindfulness intervention for stress reduction in adolescents: Design and methodology of an open-label, parallel group, randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2016, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.; Semple, R.J.; Rosa, D.; Miller, L. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Results of a pilot study. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2008, 22, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, D.; Johnson, K.; Stewart, M.; Magyari, T.; Hutton, N.; Ellen, J.M.; Sibinga, E.M. Perceptions, experiences, and shifts in perspective occurring among urban youth participating in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, A. Center for mindful awareness. Available online: http://centerformindfulawareness.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- Thompson, M.; Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. Mindfulness with children and adolescents: Effective clinical application. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanh, T.N. Planting Seeds: Practicing Mindfulness with Children; Parallax Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- Oral, R.; Ramirez, M.; Coohey, C.; Nakada, S.; Walz, A.; Kuntz, A.; Benoit, J.; Peek-Asa, C. Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: The future of health care. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luce, H.; Schrager, S.; Gilchrist, V. Sexual assault of women. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 81, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.M. Recall of childhood trauma: A prospective study of women’s memories of child sexual abuse. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 62, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, M.L.; Courage, M.L.; Peterson, C. Intrusions in preschoolers’ recall of traumatic childhood events. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1995, 2, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiser-Stedman, R.; Smith, P.; Yule, W.; Glucksman, E.; Dalgleish, T. Posttraumatic stress disorder in young children 3 years posttrauma: Prevalence and longitudinal predictors. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Du, C.; Zhang, W. Prevalence and predictors of somatic symptoms among child and adolescents with probable posttraumatic stress disorder: A cross-sectional study conducted in 21 primary and secondary schools after an earthquake. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keng, S.L.; Tong, E.M. Riding the tide of emotions with mindfulness: Mindfulness, affect dynamics, and the mediating role of coping. Emotion 2016, 16, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teper, R.; Inzlicht, M. Meditation, mindfulness and executive control: The importance of emotional acceptance and brain-based performance monitoring. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|

| Decreased anxiety | Sibinga et al., 2013 [78] |

| Jee et al., 2015 [80] | |

| Decreased rumination | Sibinga et al., 2013 [78] |

| Decreased school related stress, coping with stress | Sibinga et al., 2013 [78] |

| Jee et al., 2015 [80] | |

| Flatter cortisol curve | Sibinga et al., 2013 [78] |

| Lower levels of somatization | Sibinga et al., 2016 [79] |

| Biegel et al., 2009 [87] | |

| Decreased depressive symptoms | Sibinga et al., 2016 [79] |

| Kuyken et al., 2013 [83] | |

| Effectiveness in social gains | Jee et al., 2015 [80] |

| Classroom behavior | Black et al., 2015 [86] |

| van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2012 [85] | |

| Decreased hostility | Biegel et al., 2009 [87] |

| Sibinga et al., 2016 [79] | |

| Decreased suicidal ideation | Britton et al., 2014 [84] |

| Decreased self-harm | Britton et al., 2014 [84] |

| Reduced child abuse potential by parents | Dawe and Harnett, 2007 [95] |

| Conflict avoidance | Sibinga et al., 2014 [81] |

| Improved attention | van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2012 [85] |

| Greater well-being | Kuyken et al., 2013 [83] |

| Decreased post traumatic symptoms severity | Sibinga et al., 2016 [79] |

| Population | Program | Instruction | Setting | Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public urban middle school (5th–8th grade; avg. 12 years), n = 300 | Adapted MBSR | Trained MBSR instructors and personal practice 10+ years | School | 12 weekly 50-min sessions | Sibinga et al., 2016 [79] |

| Foster care youth ages 14–21, n = 42 | Adapted MBSR | Psychologist with expertise in mindfulness, two pediatrician lead group activities | Conference room of a joint family visitation and clinic space | 10 weekly 2-h sessions | Jee et al., 2015 [80] |

| Kindergarten through 6th grade, low-income and ethnic minority students, n = 409 | Mindful Schools (MS) Program or MS Plus | MS instructor with 3–20 years mindful meditation experience and classroom teacher facilitated | School | 5-week (MS) or 7-week (MS Plus), 15-min sessions running three times per week | Black and Fernando, 2014 [118] |

| Ages 13–21, underserved youth, n = 43 | Adapted MBSR | Instructors trained in MBSR, 10+ years’ experience | Primary care pediatric clinic | 8 weekly 2-h sessions | Sibinga et al., 2014 [81] |

| Middle-school, urban youth, n = 41 | Adapted MBSR | Trained MBSR instructor, 10+ years’ experience | School | 12 weekly 50-min sessions | Sibinga et al., 2013 [78] |

| Adolescents ages 12–16 years, multiple schools, n = 522 | School teacher facilitated adapted MBSR (Mindfulness in Schools Project – UK) | Teachers trained by instructors with MBSR training | School | 9-week | Kuyken et al., 2013 [83] |

| 6th grade students, n = 101 | Meditation instruction and student writing exercises | One teacher with meditation training and 5+ years’ experience, one teacher who completed MBSR course, no experience | School | Daily for 6 weeks | Britton et al., 2014 [84] |

| Adolescents ages 14–18, n = 104 | Adapted MBSR | Instructors MBSR trained | Outpatient psychiatric facility | 8-week, 2 h/week, home 20–25 min homework daily | Biegel et al., 2009 [87] |

| Age 11–15 years, with ADHD, parents, and tutors; n = 38 | Adapted MBSR combining Mindfulness in Schools Project, and methods for children with ADHD | Instructors trained in MBSR | Group program at an academic treatment center | 8-week | van de Weijer-Bergsma et al., 2012 [85] |

| Ages 13–21, HIV infected, n = 11 | Adapted MBSR | Instructor trained in MBSR, prior experience | Group at specialty HIV clinic | Eight 2-h sessions and a 3-h retreat | Sibinga et al., 2008 [82] |

| Program Title | Website |

|---|---|

| Inner Resilience Program | http://www.innerresilience-tidescenter.org/ |

| Wellness and Resilience Program | http://sbsd.schoolfusion.us/modules/cms/pages.phtml?pageid=195404&SID |

| Mindful Schools | www.mindfulschools.org |

| Learning to Breathe | www.learning2breathe.org |

| Mindfulness in Schools Project (“.b”, or “Stop and Be!” curriculum) | www.mindfulnessinschools.org |

| Still Quiet Place | www.stillquietplace.com |

| Stressed Teens | www.stressedteens.com |

| Wellness Works in Schools | www.wellnessworksinschools.com |

| Center for Mindful Awareness | www.centerformindfulawareness.org |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortiz, R.; Sibinga, E.M. The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma. Children 2017, 4, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4030016

Ortiz R, Sibinga EM. The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma. Children. 2017; 4(3):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4030016

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz, Robin, and Erica M. Sibinga. 2017. "The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma" Children 4, no. 3: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4030016

APA StyleOrtiz, R., & Sibinga, E. M. (2017). The Role of Mindfulness in Reducing the Adverse Effects of Childhood Stress and Trauma. Children, 4(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4030016