1. Introduction: From the Ambivalence in Dewey’s Concept of Education to the Configuration of the Academic Field of Education

To understand what a universal theory of education might look like, we read John Dewey’s Democracy and Education following two questions: (1) How do broad concepts of education affect educational theorizing? (2) How is it that, for Dewey, an academic study of education (either in terms of philosophy of education or in terms of a science of education) can itself be educational? To us, these questions arise particularly against the background of the tradition of German Pädagogik. On the one hand, Dewey draws seminal ideas from the 19th-century development of this discourse (e.g., Hegel, Herbart, Fröbel). On the other hand, this discourse provides an interesting perspective, since in its 20th-century development, Pädagogik spent a lot of effort in deciding whether it is all about Bildung or Erziehung, and whether it is an applied field or a discipline of its own.

In our view, Dewey has prepared the ground for a way of theorizing education that can avoid the pitfalls of both of these forced choices. In fact, his concept of education plays a pioneering role in finding a broad outlook on the social process of education that is neither restricted to frameworks of formal education nor to one-sided subjectivity-focussed concepts of education. We also consider his understanding of philosophy of education to pave the way for freeing educational theory from subordinating itself to disciplines like philosophy, sociology, or psychology. Thus, Dewey shows that genuine educational theorizing is not just an application of established concepts such as society to educational questions.

Hence, to point out how theorizing education according to Dewey proceeds, we will re-read Democracy and Education on a rather large scale; i.e., focussing on the conceptual framework and the understanding of philosophy. First, we will show how Dewey begins Democracy and Education with a seminal plead for a broader understanding of education that not only focusses on formal occurrences of education. Rather, he offers an account that conceptualizes deliberate forms of education such as schooling or teaching as special cases of the educativeness of social life. This conceptual dimension of formal and informal education is paired with a second dimension that conceptualizes education as growth in terms of both a subjective and an objective development.

Second, this two-dimensional broadening of the concept of education proves to be a central piece for the construction of a universal theory of education. The merit of a universal theory of education is not only that it covers more and gives more insight, but that it opens up a new perspective for an academic study of education altogether. As a consequence, the philosophy of education can no longer be regarded just as an application of general philosophy to a specific field, a separable part, or a subdomain of the whole. At the same time, a science of education cannot be regarded a discipline assigned to a pre-defined or ontologically given section of reality named “education”. Instead, a universal theory of education enables us to view education as a core principle of all social life or as an overall dimension of sociality.

2. Two Dimensions of Educational Theorizing

In his initial reflection

Democracy and Education, Dewey attempts to broaden the concept of education opposed to concepts he deems restricted to just formal setting by embedding it into the broadest frame possible: life. At the core of this framework, he develops an analogy between the life of a single human and the life of society as a whole: “What nutrition and reproduction are to physiological life, education is to social life” [

1] (p. 12); i.e., as the underlying principle of the “social continuity of life” (p. 5), education is

the crucial part of the social life cycle, as “transmission through communication” (p. 12). Without any such form of communicative transmission “from those members of society who are passing out of the group life to those who are coming into it, social life could not survive“ (p. 6). In this sense, education is a “necessity of life” (p. 4). With this framework at hand, Dewey is able to employ his famous conceptual pairing of education with development and growth: “Since growth is the characteristic of life, education is all one with growing; it has no end beyond itself” (p. 58). When “life is development” (p. 55) and when “developing, growing, is life” (p. 55), then this translates into education insofar that “the educational process has no end beyond itself, it is its own end” (p. 55)—it is a process of “continual reorganizing, reconstructing, transforming” (p. 55).

This rather bold theoretic move of linking education with the growth of life already foreshadows the leading principle of our approach: the universality of Dewey’s theory of education (see below). However, to be able to grasp the scope of it, we need to work through the basic reframing of two traditional problems of educational discourse that go along with it. First, we will retrace Dewey’s initial decision not to restrict his theory of education to cases of formal education. Second, we will focus on the ambivalence of an objective and a subjective dimension of education induced by Dewey’s analogy between social and individual life.

First and foremost, this is a conception that clearly exceeds any “ordinary notion of education” [

1] (p. 12), which narrowly formulates the concept of education in the vicinity of schooling and teaching and by that reduces education to “imparting information about remote matters and the conveying of learning through verbal signs: the acquisition of literacy” (p. 12). Rather, such or other forms of designed conveyance (i.e., forms of deliberately shaping the young according to the current habitualities and customariness of social life) are a special case of the more general form of the necessity of societal survival despite the gradual replacement of all of its members (pp. 6–7). In his view, “the social environment exercises an educative or formative influence unconsciously and apart from any set purpose” (p. 20), not just a special set of actions but the “very process of living together educates” (p. 9).

As a subordinated step, Dewey then is able “to distinguish, within the broad educational process […], a more formal kind of education—that of direct tuition or schooling” [

1] (p. 10). However, with a broad concept of education, the difference between “the informal and the formal, the incidental and the intentional, modes of education” (p. 12) is not a distinction between education and, say, mere socialization, but it is “a marked difference between the education which everyone gets from living with others [...] and the deliberate educating of the young” (p. 9). This conceptual re-wiring allows for a refurbished understanding of what used to be thought of as the

conceptual core of educational theory in the sense that “[o]nly as we have grasped the necessity of more fundamental and persistent modes of tuition can we make sure of placing the scholastic methods in their true context” (p. 7)—that of a deliberate effort as a historically late product of societal evolution [

2] (p. 23) (see also [

1] (p. 6)).

Second, and with the same emphasis, Dewey offers a concept of education that is not restricted to the predominant individualistic view that emerges from focusing on what education is thought to be all about: personal development and growth as the effect of some social activity we call “education”. There are, however, some passages in

Democracy and Education that might lead the way to such a strategy of theorizing education from an individualistic viewpoint. In this framework, speaking about education means that any “social arrangement” [

1] (p. 9) is “educative to those who participate in it” (p. 9), in the sense that the “social environment forms the mental and emotional disposition of behavior in individuals by engaging them in activities that arouse and strengthen certain impulses” (p. 20). When Dewey speaks about how “every social arrangement is educative

in effect” (p. 12; emph. JB/HS), he is definitively not talking about a certain structure of the social process of communication, but about what communication does to the individual in general. That is, communication is educative in the sense of having an educative effect. In this approach, technically, communication or social life is educative because it has certain effects like learning, development, or socialization—in general “making individuals better fitted to cope with later requirements” (p. 62). As the effect of education (as personal development) surely lies beyond the process of education itself (as social process), this sharp reading is not on par with the principles of growth and self-renewing of life. In any case, though, a theory of education with a conceptual focus on the individual effects of social life is one-sided and gives too much away.

However, this is not the whole story you get from Dewey’s concept of education. With Dewey, one could question whether an individualistic account specifying education by specifying certain (i.e., planned, desired, educative) outcomes is all that is left for educational theory. Rather, after taking on a broad concept of education, he uses the (seemingly individualistic) concepts of experience and growth to bridge any opposition between subjective and objective dimensions of culture. In light of the initial outset on the renewal of social life, the continual reorganizing of society is also to be perceived in terms of developmental growth.

According to Dewey’s perspective on the self-renewal of social life, a concept of education relying on a concept of the

educative effects of social life could be turned into an understanding of education in the sense of an

educational structure of social life. After all, it is not the renewal of the individual life that Dewey is after initially, but the renewal of society or societal life: “Society exists through a process of transmission quite as much as biological life” [

1] (p. 6), and the “life of the group goes on” (p. 5), although “[e]ach individual, each unit who is the carrier of the life-experience of his group, in time passes away” (p. 5). Dewey even reminds us that the continuation of social life “is not dependent upon the prolongation of the existence of any one individual” (p. 4), but on a “continuous sequence” (p. 4) of the “very nature of life to strive to continue in being” (p. 12) through “constant renewals” (p. 12) on a societal level. In other words, “a community or social group sustains itself through continuous self-renewal” (p. 14).

This seminal thought offered in the general outset of

Democracy and Education entails that the ambivalence between a subjective and an objective dimension is twofold. On the one hand, in theorizing education in the framework of the problem of the “continued existence of a society” [

1] (p. 7) or of society determining “its own future in determining that of the young” (p. 47), Dewey surpasses plain individualistic conceptions of education—at least in the basic architecture of his theory of education. He shifts the talk of renewal by education away from matters of the renewal of a single human being by educative experience and towards an understanding of the educational renewal of society. This reframing results in a shift of the concept of renewal itself. Normally, renewal would be distinguished from conservation—i.e., seen as something that would have to be deliberately, by design, brought up against “things staying the same”. Despite his own bias for educational reform and favoring a progressive democratic society “which has the ideal of such change” (p. 87), Dewey’s basic notion of social life makes use of a joint concept of renewing and conserving, of conserving society by renewing habits in view of losing and gaining members.

On the other hand—and even more deeply rooted—we cannot understand society without simultaneously taking the figure of self-renewal into account. Self-renewal is

the principle of society. “Society not only continues to exist

by transmission,

by communication, but it may fairly be said to exist

in transmission,

in communication” [

1] (p. 7). Maybe, when putting a little too much attention to this detail, we would say that education is—although Dewey explicitly says otherwise (p. 87)—not conceptualized as a function of society by which it manages to sustain itself or by which it leads to certain effects like individualized or socialized members. Rather in analogy to an illocutionary speech act as “performance of an act

in saying something” [

3] (p. 40) instead of perlocutionary acting

by saying something, society iterates

in transmission. This iterative self-renewal

is society. In this view, the process of iteration is not at the conceptual periphery, but constitutes the conceptual core of society—and so is education.

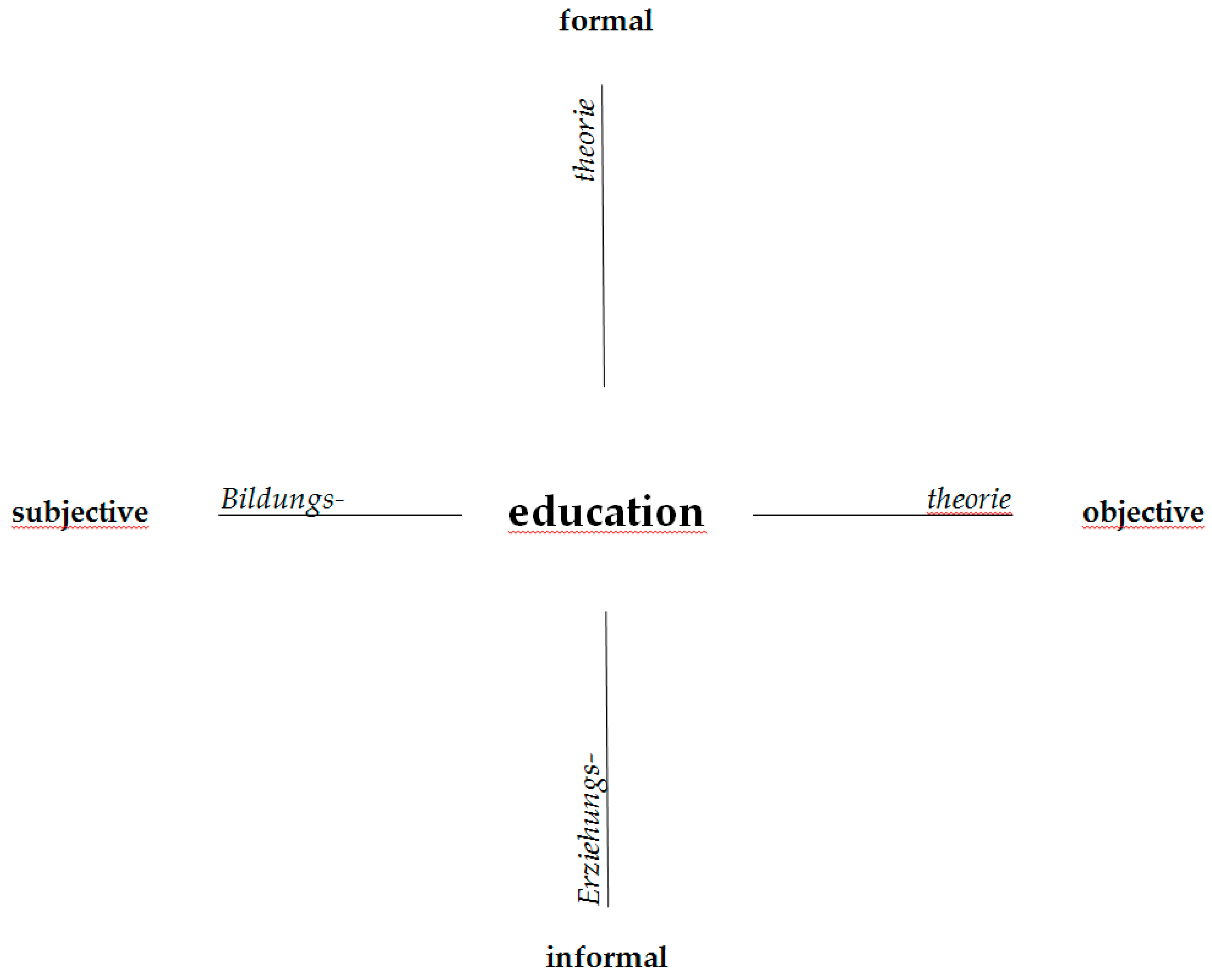

To systematize these observations, Dewey’s concept of education as plotted in

Democracy and Education can be analyzed as comprising two dimensions of pedagogical reflection (

Figure 1). With this structure, he is not just saying a full understanding of education needs to encompass both aspects, which in the German discourse are commonly termed

Erziehung and

Bildung. In both of these respects, he accentuates that we need to put conceptional stress on the whole spectrum from formal to informal modes of education, from subjective to objective modes of education.

On the one hand, he picks up the distinction of formal and informal education (

Erziehung), and he is opting for a broad understanding of education encompassing not just intentionalized, institutionalized, or otherwise designed education. Teaching would be the paradigm case of education in this “intentional use” [

4] (p. 42); i.e., understood from its planning force or cause. Still emphasizing education in the dimension of

educating activity, he manages to focus not just doings in order to educate, but all social activities as educating: the core of social life happens to be a process of education. On the other hand, Dewey presents education in terms of

educative experience. In this respect he follows—deliberately or not—the early German tradition of

Bildung represented particularly by Herder and Hegel. For them,

Bildung encompasses both a subjective and an objective dimension of culture and habits [

5,

6]. In the common understanding, this seems to be a clear case of a “success use” [

4] (p. 42) or an effect use of the term ‘education’, as it might be thought of as being shaped with a focus on its effects like individual learning, personal development, or subjective growth. However, in keeping the objective interpretation of social conduct alive, Dewey understands his characteristic concepts of growth and experience as terms to describe individual and societal processes to the same extent.

Dewey’s two-dimensional theory of education, as it has been reconstructed here, takes a broad outlook: in its first dimension, it avoids a widespread “scholastic” view of education by focusing not only on formal but also on informal education. In its second dimension, it also avoids a widespread individualistic view on education by referring not only to growth of the individual but also to growth of the social setting (democracy) on the whole. By this broad outlook, Dewey laid the foundations for a universal theory of education where education is not a separated realm of social life, but a pervasive aspect of it.

In the following, we would now like to investigate the relationship between Dewey’s theory of education and his theory of the academic field dealing with education as its subject matter. Our hypothesis is that his universal theory of education has consequences for the configuration of education as an academic field, so that there is a close relationship between his theory of the subject matter in question (Gegenstandstheorie) and his theory of education as an academic field (Wissenschafstheorie).

3. The Conceptual Relationship between Philosophy and Education

In

Democracy and Education, Dewey’s main concern is not the question of whether there is a “science of education” or whether there can be a “science of education”. These questions are dealt with in the later essay “Sources of a Science of Education”. In

Democracy and Education, Dewey rather connects his theory of education with a specific understanding of “philosophy of education”, particularly in the important chapter 24 that (to some extent) summarizes the general outlook developed in his book. Here, we find the famous statement “philosophy may even be defined as the general theory of education” [

1] (p. 338), a view that must still—or even more than in Dewey’s times—puzzle academic philosophy. Why should philosophy as a whole be equivalent to a general theory of education? What might hold true for a philosophy of education seems to be doubtful for philosophy altogether.

Dewey’s vantage ground, however, is not contemporary academic philosophy where “philosophers become a specialized class which uses a technical language” [

1] (p. 338). It is rather the ancient view of philosophy as “love of wisdom” which has a direct impact on “the conduct of life” (p. 334). In this respect, there is an “intimate connection between philosophy and education” (p. 338); in other words, a

conceptual relationship between philosophy and education. In its ancient sense, philosophy is educational from the beginning, as it is not only “symbolic” or “verbal”, but practically “forming fundamental dispositions, intellectual and emotional, towards nature and fellow men” (p. 338). Very soon, however, philosophical questions were “cut loose from their original practical bearing upon education and were discussed on their own account; that is, as matters of philosophy as an independent branch of inquiry” (p. 340).

Interestingly, in its line of argument, Dewey’s critical account of this development towards a specialized academic philosophy resembles his differentiation of formal education out of a broader context of informal education, which he outlines in the first two chapters of Democracy and Education. In both cases, Dewey criticizes a one-sided focus on the formal or scholastic mode—both of education and philosophy—that threatens to separate both from their original broader practical context.

Dewey’s critical account of this development is linked with a further argument that displays another striking similarity between education and philosophy. Like education, philosophy also cannot be defined “simply from the side of subject matter” [

1] (p. 334). Philosophy rather denotes an “outlook upon life”, a “disposition toward the world” or a “general attitude toward it” (p. 334). There is no particular subject matter that is inherently philosophical and therefore clearly distinguishable from non-philosophical subject matters. Respectively, a universal theory of education comes to the same conclusion for education. Since education cannot be treated as a separated realm of social life but rather has to be regarded as a pervasive aspect of it, the academic field of education cannot be defined from the side of subject matter. In

The Sources of a Science of Education, Dewey left no doubt about this: “There is no subject-matter intrinsically marked off, earmarked so to say, as the content of educational science” [

7] (p. 24). From the perspective of a universal theory of education, it is consistent to say that “educational science has no content of its own” (p. 25). Or, to put it the other way around: every subject matter, whatsoever, can be treated with regard to its educational aspects, implications, and consequences.

Thus, the “intimate connection between philosophy and education” [

1] (p. 340) is grounded on a kind of self-resemblance between them. Rather than representing specialized ontological spheres of their own, they both stand for a general outlook upon life. That is why any academic treatment of education—be it a philosophy or a science of education—cannot have a specialized subject matter put in front as an object of investigation. Instead, the universal outlook of education enforces a

reflective turn on the academic field of education. If education is a universal aspect of social life, neither a philosophy of education nor a science of education possess a neutral (i.e., a non-educational) ground from where they could objectify education. Hence, they both have to reflect on themselves with regard to their own educational qualities. In this reflective turn, any

philosophy of education becomes an

educational philosophy. Respectively, a “science of education” turns into an “

educational science” [

7] (p. 16).

4. A Universal Theory of Education and the Configuration of the Academic Field of Education

We can now consider how Dewey’s universal theory of education relates to the two main configurations of the academic field of education. On the one hand, there is the idea of a science of education as a

discipline of its own as it has been developed in continental Europe (particularly German-speaking countries), while on the other hand, education is understood as an

applied field of foundational disciplines (like psychology, sociology, history, philosophy) [

8]. We proceed on the assumption that a universal theory of education is not indifferent towards the way the academic field of education is understood and organized. Clarifying this relationship at the same time helps to expose the significance of Dewey’s universal theory of education for today’s debates about a science of education.

To deal with this issue, one not only has to go beyond

Democracy and Education and turn to other writings like the essay

The Sources of a Science of Education; one must also go beyond Dewey’s own explicit statements towards this issue and—as already indicated above—reflect on the implications and consequences of a universal theory of education regarding a science of education. Strikingly, the starting point in his essay is not a universal theory of education, but rather a universal theory of science in terms of “systematic methods of inquiry” [

7] (p. 4) that finally leads to the statement that education is “an activity which

includes science within itself” (p. 40). Yet another striking difference to

Democracy and Education is the fact that the later essay rather focusses on examples of formal education; i.e., the relevance of an educational science for teachers and schooling. Nevertheless, it is noticeable that, under the surface, the universal theory of education as developed in

Democracy of Education seems to become noticeable in the later essay, as well.

To get straight to the point: the results of an investigation on the relationship between Dewey’s universal theory of education and the implications and consequences for the academic field of education are anything but unambiguous. On the one hand, Dewey’s universal theory of education is at odds with both a disciplinary approach and the idea of education as an applied field for foundational disciplines. On the other hand, a universal theory has the potential to reconnect to both configurations of the academic field, if these configurations are understood slightly different than today. Both will be outlined in the following.

If one starts with Dewey’s own statements in

The Sources of a Science of Education, one gets the impression that he clearly rejects a disciplinary approach and sides with the idea of education as an applied field for foundational disciplines. Under the headline “Science of Education not Independent”, he states that “educational practices furnish the material that sets the problems of such a science, while sciences already developed to a fair state of maturity are the sources from which material is derived to deal intellectually with these problems. There is no more a special independent science of education than there is of bridge making. But material drawn from other sciences furnishes the content of educational science when it is focused on the problems that arise in education” [

7] (p. 18). So far, it seems as if this is just an early articulation of the understanding of the academic field of education as it has become dominant throughout the 20th century in English-speaking countries. Education is regarded as an applied field, while “the source of really scientific content is found in other sciences” (p. 21).

This unambiguousness disappears, however, when we read about the idea of the “Teacher as Investigator” [

7] (pp. 23–24) and the critique that “if teachers are mainly channels of reception and transmission, the conclusions of science will be badly deflected and distorted before they get into the minds of pupils” (p. 24). The warning against a misleading transmission model of foundational disciplines is supported by the idea that educational science is not entirely dependent on intellectual resources of other disciplines but, in fact, has a source of its own in the very educational experience made in practices of education: “Concrete educational experience is the primary source of all inquiry and reflection because it sets the problems, and tests, modifies, confirms or refutes the conclusions of intellectual investigation” (p. 28).

A simple transmission model is particularly misleading, since the generalizations of science—gained by means of quantification—must be tested in educational experience by the judgement of the practitioner. The “parent or educator deal with situations that never repeat one another” [

7] (p. 33). “Judgement in such matter is of qualitative situations and must itself be qualitative” (p. 33).

Thus, the whole essay about

The Sources of a Science of Education develops a dynamic in which the idea of education as an applied field of foundational disciplines is deconstructed step by step. Particularly, the final chapters about “Educational Values” and the “General Conclusion” argue for a self-confidence of education as a field that “is autonomous and should be free to determine its own ends, its own objectives” [

7] (p. 38). In contrast to the idea of education of an applied field of foundational disciplines, the essay concludes with the idea of education as a reflecting experience that “

includes science within itself” (p. 40). Education is not blind practice having science(s) external to it. It is “itself a process of discovering” (p. 38), both what its values and objectives are concerned and with respect to determining the educational meaning of findings provided by other disciplines.

It is important to note, though, that the critique of the idea of education as an applied field for foundational disciplines does not simply result in arguing for the idea of a science of education as a discipline of its own. A disciplinary configuration of the academic field of education is rejected as soon as disciplines pretend to mirror material objects in the real world (as bridges in a pretended discipline of bridge making) and claim some exclusive responsibility for them. This pretension was characteristic for major proponents of

Geisteswissenschaftliche Pädagogik who argued that the autonomy of a science of education as a discipline was based on the autonomy of education as a differentiated cultural sphere [

9]. Yet, the idea that the order of disciplines mirrors a pre-established ontological order of (natural, social, or cultural) spheres is not only unreasonable; it is also incompatible with the outlook of a universal theory. At this point, it is also important to add that this holds true for

any universal theory. A universal theory of education has no exceptional status. The same would apply, for instance, to a universal theory of the economical or the political. This circumstance is due to a factor of sociality that the sociologist Niklas Luhmann termed “poly-contexturality” [

10] (pp. 666–668): since any sense making happens by differentiation, and since once a differentiation is made, anything else can be observed by virtue of this specific differentiation, there are different viewpoints evolving simultaneously.

Although a disciplinary configuration—understood as indicated above—is incompatible with a universal theory of education, there is nevertheless some potential for reconnecting to a disciplinary approach. This reconnection, however, presupposes a different understanding of the subject matter of scientific investigation. A discipline is not constituted by a material object in the real world, but by a perspective on a

formal object of investigation [

11]. This understanding of the subject matter of investigation is rather compatible with the idea of a universal theory which does not claim to represent sections of reality but rather a particular perspective on any subject matter of investigation whatsoever [

12] (pp. 80, 131).

The importance of a disciplinary perspective becomes apparent in dealing with the knowledge of other disciplines. Without a disciplinary perspective, the conclusions of other sciences are adopted according to the simple transmission model that Dewey explicitly problematizes. Throughout his essay, Dewey expounds the danger of an unfiltered reception of knowledge from other disciplines in the field of education. The background for this mode of reception is a misled understanding of science altogether. Science is “regarded as a guarantee that goes with the sale of goods rather than a light to the eyes and a lamp to the feet” [

7] (p. 7). In contrast to the transmission model, Dewey develops a mode of reception in which the knowledge of other disciplines needs to be

translated to the specific perspective of educators: “it must operate through their own ideas, plannings, observations, judgements. Otherwise it is not

educational science at all, but merely so much sociological information” (p. 39). This translation, however, presupposes a perspective from where knowledge from other disciplines can be recontextualized and judged in its educational relevance.

Admittedly, Dewey is not arguing explicitly for a science of education as a discipline. Particularly, he does not argue for a science of education which is set in juxtaposition to education as an art. “If there were an opposition between science and art, I should be compelled to side with those who assert that education is an art. But there is no opposition, although there is a distinction” [

7] (p. 6). Similar to German

Geisteswissenschaftliche Pädagogik, Dewey is rather arguing for a continuity between education as an art and an educational science that is grounded in a common educational perspective. This common ground, again, presupposes a universal theory of education from where not only philosophy but also science can discover and reflect on its

educational dimension.

One might call this educational perspective a disciplinary perspective in terms of a mode of observation that characterizes a discipline as a specific context of communication. More important than how to the name this approach is to see that it allows for reconnecting both to a certain understanding of a disciplinary configuration of the academic field of education and to a certain understanding of education as an applied field for other disciplines. One the one hand, it is an educational perspective, developed in a universal theory of education, that creates a specific formal object of investigation that characterizes a disciplinary observation. On the other hand, it is an educational perspective that allows for connections to be drawn to knowledge from other disciplines by making sense of it educationally.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Concluding, we would like to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of a universal theory of education as developed in Democracy and Education. So far, we have pointed out four merits.

The first and one of its obvious merits is that a universal theory of education helps to identify certain biases in theorizing education characteristic of contemporary discourses; for instance, their focus on formal education in institutionalized settings or on individualistic notions of growth in terms of learning and development. Observed from a universal theory, these occurrences of education can be classified as special cases within a broader concept of education. In this context, it is exactly the ambivalence of the English term “education” that has to be regarded as an advantage, while the German discourse requires a decision between Bildung and Erziehung which imply different perspectives of theorizing education. Once these have diverged, it is often hard to reconnect them. When Dewey’s German translator decided for “Demokratie und Erziehung” his readers got the false impression that the book was not dealing with Bildung.

Second, Dewey’s concept of education not only entails the dimensions of Bildung and Erziehung, it also avoids a rash separation of education and socialization. Instead of just focusing on a narrow understanding of the former while leaving the latter to sociology, a universal theory of education introduces an internal distinction within the concept of education (formal/informal) that covers both modes as subject matters of educational research.

The third marked merit of a universal theory of education is that it allows for a self-confident way to theorize education whereby it becomes possible to investigate and reflect any subject matter with respect to its educational aspects—including the process of theorizing itself. By the way, it may be worth noting that the failure to arrive at such a self-confident way of theorizing education might (at least partially) be the reason for the widespread disdain for educational science, both in the academic field and in the public discourses on education.

Finally, an important merit of a universal theory of education is that it allows for a new understanding of the academic field of education. As indicated above, it is both critical of a configuration of education as a discipline of its own and of a configuration of education as an applied field—at least in terms of the dominant ways in which these configurations are understood. At the same time, a universal theory of education opens up a way of reconnecting to both configurations, provided that they are understood differently.

For the English-speaking discourse, Dewey’s universal theory of education entails a strong critique of the dominant way philosophy of education is understood and practiced by application of philosophical thought as it is already established by certain philosophical schools or “-isms” on educational subject matters. The way in which

Democracy and Education is written gives evidence for a completely different approach. Dewey does not begin by explaining what philosophy is or what messages a certain school of philosophical thought contains just to apply these, as a corollary, to education [

11,

13]. Conversely, he starts out by theorizing education in an independent way right from the beginning, while only in the final chapters he explains what he regards as philosophy of education—or more precisely, he explains that what he has been developing in this book can be regarded as an educational philosophy. References to certain philosophers or philosophical schools of thought are rather rare examples. This is not only due to the conventionalities of academic writing in Dewey’s times, but also to his genuine way of beginning and proceeding with his genuine approach of theorizing education we focused on. It may be noted that this way of theorizing education corresponds to the “general features of a reflective experience” [

1] (p. 157) as expounded in the chapter “Experience and Thinking” in

Democracy and Education. In both cases, Dewey’s approach does not start with theory (like schools of philosophical thought), but with a phenomenon in a field of “primary experience” [

14] (p. 15), moving back to reflect on it and moving ahead to theorize its meaning by exploring its (universal) scope and its interconnection to other phenomena (like democracy, scientific method, art, etc.).

For the English-speaking discourse but also for the interdisciplinary field of

Bildungswissenschaften in terms of learning sciences [

15] that has recently developed in German-speaking countries, Dewey’s universal theory of education entails another critique—namely, a critique of the widespread way of dealing with knowledge of other disciplines in the field of education. Due to a lacking theory of education, this knowledge often finds an unfiltered reception. There numerous findings from other disciplines that claim to be immediately relevant for education as there are numerous theories in education [

16], while—without a theory of education—there is often no idea how make sense of them educationally.

For the German-speaking discourse, Dewey’s universal theory of education particularly entails a pronounced critique of a misled understanding of a science of education in terms of a discipline that defends its exclusive responsibility for education as a differentiated domain of the social world. A universal theory of education not only goes beyond a differentiated domain, it can also discover that there are other universal theories (of politics, economics, etc.) around that are dealing with education from their own perspective.

Another lesson to be learned from Dewey in the German-speaking discourse is worth noting as well. Especially in the turn from

Geisteswissenschaftliche Pädagogik to

Erziehungswissenschaft as a modern discipline of social science, the former understanding of

Pädagogik as “reflection theory” or as a “réflexion engagée” [

17] (p. 18) was found to be outdated, an indicator of a premature status of the academic field that had not yet arrived at empirical forms of scientific objectification. From a Deweyan perspective, however, this departure from

Pädagogik as “reflection theory” may turn out to be not only hasty, but also pretentious. A universal theory of education necessarily takes on the form of a “reflection theory” as a consequence of its mode of theorizing. In contrast to the tradition of

Geisteswissenschaftliche Pädagogik, however, a “reflective turn” is not a normative requirement for educators and their professionalism, but rather a structural implication of a certain way of theorizing education that takes itself to be educational.

One of the critical queries to Dewey’s universal theory of education would be whether it is able to acknowledge the idea of poly-contexturality; i.e., the fact that there are simultaneously different universal theories with equal rights. Some of Dewey’s writings indicate that he is not only well aware of this fact, but that he himself contributes to a poly-contextual way of theorizing by investigating different dimensions of experience such as arts or religion—each of them having a universal outlook. In any case, the structure of the argument is similar to the one developed in Democracy and Education. Dewey starts out with a critique of a one-sided focus on the differentiated, formal, or institutionalized mode of arts or religion just to remind us of the aesthetic and religious dimensions of any experience. Compared to this, a universal theory of education has no exceptional status. It is only dealing with one among other universal dimensions of experience.

Nevertheless, Dewey’s oeuvre also provides evidence for a different answer to this query; i.e., evidence that a privileged status is ascribed to education. For Dewey, a universal theory of education is not only one universal theory on par with others; it rather claims a superior status insofar as any other dimension of experience is measured by its contribution to an educative experience. For Dewey, “the ultimate significance of every mode of human association lies in the contribution which it makes to the improvement of the quality of experience” [

1] (p. 12). Dewey claims this to be “a fact” that is only “most readily recognized in dealing with the immature” (ibid.), but it nevertheless seems to be treated as a general truth. The primacy of the educational dimension of experience becomes even more apparent in writings where the tension between the educational dimension of experience and other dimensions gain center stage. In “The Social-Economic Situation and Education” [

18] (pp. 43–76), for instance, Dewey together with his co-author John L. Childs develops the utopian idea of a “planning society” in which any institution is judged by its educative effect: “In such a national life, society itself would be a function of education, and the actual educative effect of all institutions would be in harmony with the professional aims of the special educational institution” (p. 65). More evidence could be found throughout his work that Dewey has in fact developed a pedagogical world view which not only is universal in its perspective, but also privileged compared to other world views [

19].

On the centenary of Democracy of Education, however, it is fair enough to celebrate the book not for its contribution to a sociological theory of a poly-contextural (post-)modern society, but—first and foremost—for its contribution to a universal theory of education which still entails important lessons to learn from.