Constructing U.K. Core Inflation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Definition of Core Inflation

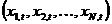

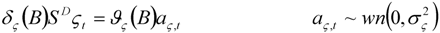

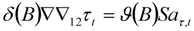

, and that each price is assumed to have an unobserved component (UC) representation

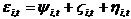

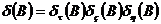

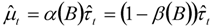

, and that each price is assumed to have an unobserved component (UC) representation  , where

, where  is the trend component and

is the trend component and  contains all other components. If the prices are observed monthly then

contains all other components. If the prices are observed monthly then  measures the monthly trend rate of inflation and

measures the monthly trend rate of inflation and  measures the annual trend rate of inflation of the ith price, where

measures the annual trend rate of inflation of the ith price, where  and

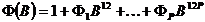

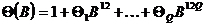

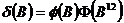

and  are the first and seasonal (annual) difference operators defined using the lag operator B, where

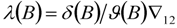

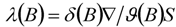

are the first and seasonal (annual) difference operators defined using the lag operator B, where  . Given a set of weights

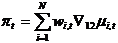

. Given a set of weights  , a measure of, say, annual core inflation may then be defined as

, a measure of, say, annual core inflation may then be defined as

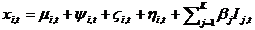

are intervention variables modelling various types of (deterministic) outliers, while the (stochastic) non-trend component is decomposed as

are intervention variables modelling various types of (deterministic) outliers, while the (stochastic) non-trend component is decomposed as  , where

, where  is the cyclical component,

is the cyclical component,  is the seasonal component and

is the seasonal component and  is the irregular component.

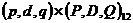

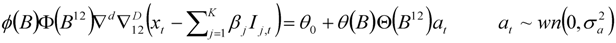

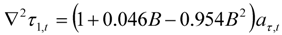

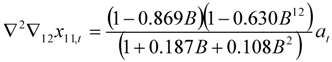

is the irregular component.  model for each price, now denoted generically as

model for each price, now denoted generically as  , of the form

, of the form

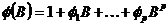

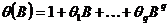

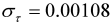

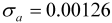

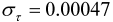

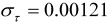

denotes a white noise series of innovations with zero mean and variance

denotes a white noise series of innovations with zero mean and variance  . The various lag polynomials are defined as

. The various lag polynomials are defined as

,

,  ,

,  and

and  . Writing (2) as (with

. Writing (2) as (with  for simplicity)

for simplicity)

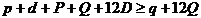

using the following rule. If

using the following rule. If  denotes the frequency of a root of

denotes the frequency of a root of  expressed in radians, then if

expressed in radians, then if  the root is allocated to the trend-cycle

the root is allocated to the trend-cycle  ; if

; if  ,

,  , the root is allocated to the seasonal,

, the root is allocated to the seasonal,  ; and if

; and if  takes any other value then it is allocated to the irregular component,

takes any other value then it is allocated to the irregular component,  . Hence cycles with a period longer than a year will be part of the trend-cycle, while cycles with a period less than a year will go into the irregular. This rule allows the autoregressive polynomial to be factorized as

. Hence cycles with a period longer than a year will be part of the trend-cycle, while cycles with a period less than a year will go into the irregular. This rule allows the autoregressive polynomial to be factorized as  and (3) to be rewritten

and (3) to be rewritten

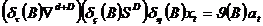

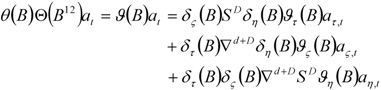

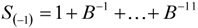

is the annual aggregation operator, so that

is the annual aggregation operator, so that  . The components will thus have models of the form

. The components will thus have models of the form

,

,  and

and  being mutually uncorrelated. Consistency between the “reduced form” (3) and the “structural model” (4) requires the moving average polynomials in the structural model to satisfy the identity

being mutually uncorrelated. Consistency between the “reduced form” (3) and the “structural model” (4) requires the moving average polynomials in the structural model to satisfy the identity

is employed. SEATS provides algorithms for obtaining this estimator in finite samples, where backcasts and forecasts calculated from the reduced form (3) are used to extend the observed series to allow the WK estimator to be computed (and, indeed, WK estimators of the other components) throughout the entire sample.

is employed. SEATS provides algorithms for obtaining this estimator in finite samples, where backcasts and forecasts calculated from the reduced form (3) are used to extend the observed series to allow the WK estimator to be computed (and, indeed, WK estimators of the other components) throughout the entire sample. , the cycle can be removed to leave just the trend

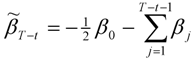

, the cycle can be removed to leave just the trend  by using a low-pass filter, of which several alternatives are available (for example, the Hodrick-Prescott [14] and Baxter-King [15] filters). We propose using the low-pass version of the Christiano and Fitzgerald random walk (with drift adjustment) CF filter [16], which has been shown to be robust and a close to optimal filter for a wide range of time series. The form that the filter takes here is

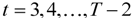

by using a low-pass filter, of which several alternatives are available (for example, the Hodrick-Prescott [14] and Baxter-King [15] filters). We propose using the low-pass version of the Christiano and Fitzgerald random walk (with drift adjustment) CF filter [16], which has been shown to be robust and a close to optimal filter for a wide range of time series. The form that the filter takes here is

is the asymmetric high-pass filter that passes all components with periods of oscillation less than

is the asymmetric high-pass filter that passes all components with periods of oscillation less than  (this filter provides an optimal linear approximation to

(this filter provides an optimal linear approximation to  when the data follows a random walk and extremely good performance when the data are more generally non-stationary). For

when the data follows a random walk and extremely good performance when the data are more generally non-stationary). For  the “CF filter” is

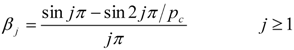

the “CF filter” is

and

and  ). The CF filter thus “takes out” of the trend-cycle all components having cycles with periods less than

). The CF filter thus “takes out” of the trend-cycle all components having cycles with periods less than  .

. 3. Core Inflation Estimates for the U.K.

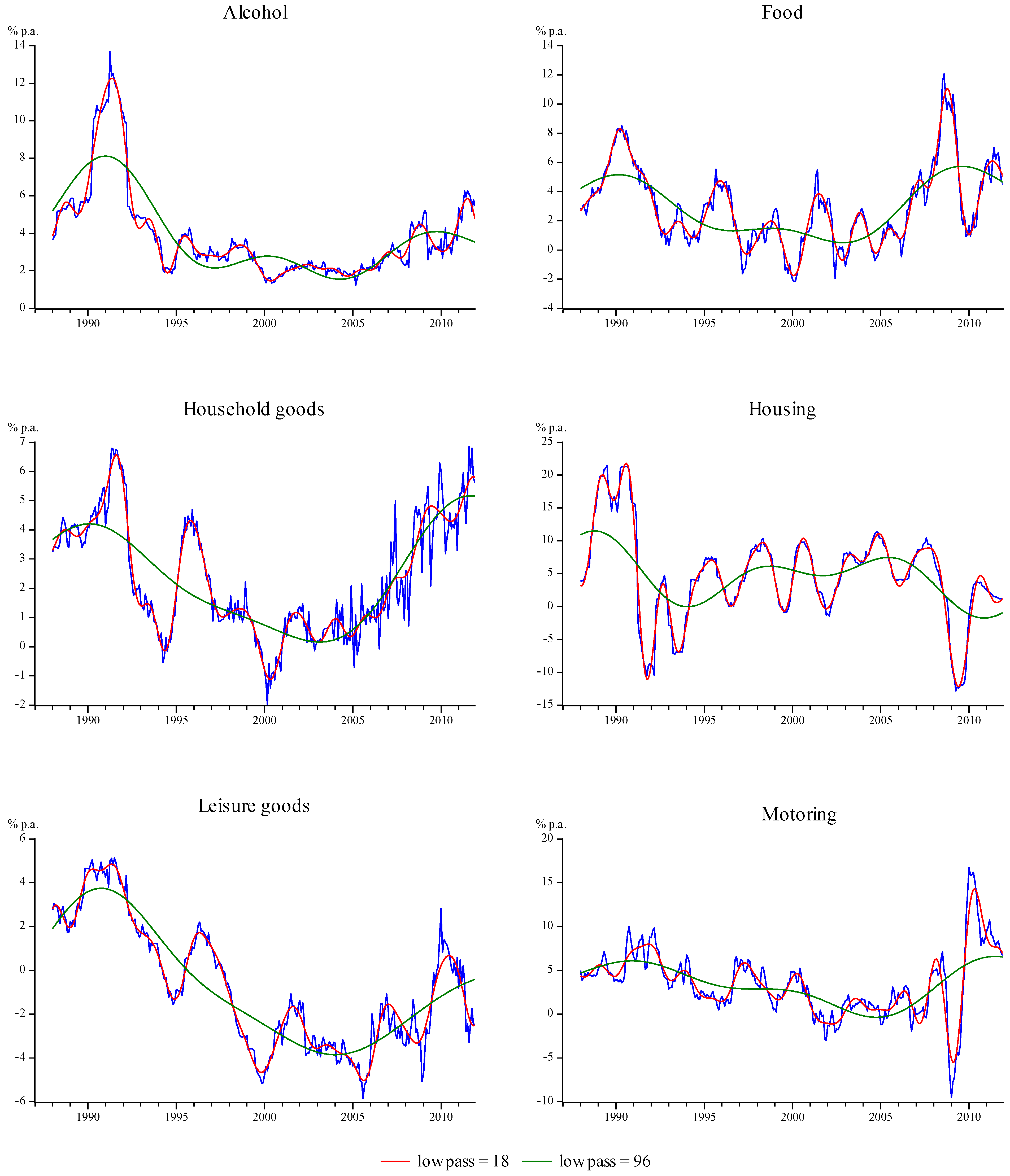

, for the six sections having the largest 2011 weights (covering approximately 70% of the RPI), along with the actual inflation rates for the sections. Two trend inflations are shown, for

, for the six sections having the largest 2011 weights (covering approximately 70% of the RPI), along with the actual inflation rates for the sections. Two trend inflations are shown, for  and 96, which pass components to the trend having periods in excess of

and 96, which pass components to the trend having periods in excess of  and 8 years respectively (these represent the typical business cycle bounds used in macroeconomics: see, for example, Baxter and King [15]). The smaller setting follows actual inflation very closely, which is not surprising given that this setting only excludes components with periods between 12 and 18 months from the trend-cycle

and 8 years respectively (these represent the typical business cycle bounds used in macroeconomics: see, for example, Baxter and King [15]). The smaller setting follows actual inflation very closely, which is not surprising given that this setting only excludes components with periods between 12 and 18 months from the trend-cycle  to obtain

to obtain  . The larger setting produces more slowly varying trends as it concentrates mainly on the long-period, low frequency components at the exclusion of higher frequency components.

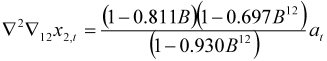

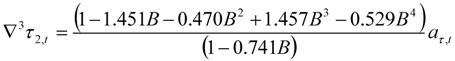

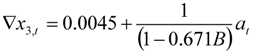

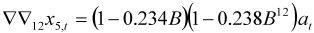

. The larger setting produces more slowly varying trends as it concentrates mainly on the long-period, low frequency components at the exclusion of higher frequency components.| Section | Reduced form | Trend-cycle |

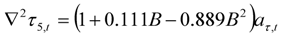

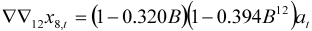

| Alcohol |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1990.04 LS; 1990.05 LS; 1991.04 LS; 2008.04 LS; 2011.01 LS; 2011.04 LS) | ||

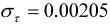

| Catering |  |  |

|  | |

| 4 outliers (1991.04 LS; 2008.12 LS; 2010.01 LS; 2011.1 LS) | ||

| Cigarettes & tobacco |  |  |

|  | |

| 5 outliers (1989.04 LS; 1991.04 LS; 1999.09 LS; 2000.04 LS; 2011.04 LS) | ||

| Clothing & footwear |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (2000.07 LS; 2008.12 LS; 2010.02 LS; 2010.04 LS; 2010.09 LS; 2011.02 LS) | ||

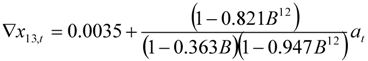

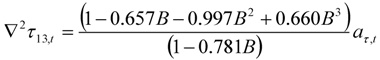

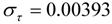

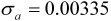

| Fares |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1990.01 AO; 2003.04 TC; 2003.12 AO; 2004.12 AO; 2006.05 LS; 2011.04 AO) | ||

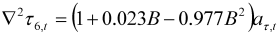

| Food |  |  |

|  | |

| 1 outlier (2008.06 LS) | ||

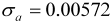

| Fuel & light |  |  |

|  | |

| 5 outliers (1990.10 AO; 2008.02 LS; 2008.09 TC; 2010.02 LS; 2010.12 AO) | ||

| Household goods |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1991.04 LS; 2006.12 AO; 2007.03 AO; 2007.06 LS; 2007.07 LS; 2008.06 AO) | ||

| Household services |  |  |

|  | |

| 3 outliers (1991.04 LS; 1995.07 LS; 2006.10 TC) | ||

| Housing |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1988.08 LS; 1990.04 LS; 1991.04 LS; 1993.01 AO; 1993.04 TC; 2008.12 LS) | ||

| Leisure goods |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1991.03 AO; 2006.02 TC; 2007.06 TC; 2008.12 TC; 2010.01 AO; 2011.06 LS) | ||

| Leisure services |  |  |

|  | |

| 6 outliers (1987.09 AO; 1988.04 LS; 1991.04 LS; 1991.09 TC; 1992.04 LS; 1992.09 TC; 2002.04 LS) | ||

| Motoring |  |  |

|  | |

| 1 outlier (2008.11 LS) | ||

| Personal goods & services |  |  |

|  | |

| 5 outliers (1994.02 AO; 1994.05 AO; 1994.08 TC; 1994.12 AO;; 1998.02 LS) | ||

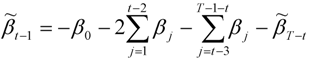

,

,  , for the sample period 1987 to 2011. The weights are updated by the ONS every year, and Figure 3 shows these section weights (the convention is that the weights sum to 1000). These weights were then used to compute annual core inflation using (1) (the weights were smoothed by linear interpolation across the last two months of one year and the first two months of the next year to avoid the (albeit small) jumps in inflation that result from the annual weight updating).

, for the sample period 1987 to 2011. The weights are updated by the ONS every year, and Figure 3 shows these section weights (the convention is that the weights sum to 1000). These weights were then used to compute annual core inflation using (1) (the weights were smoothed by linear interpolation across the last two months of one year and the first two months of the next year to avoid the (albeit small) jumps in inflation that result from the annual weight updating).

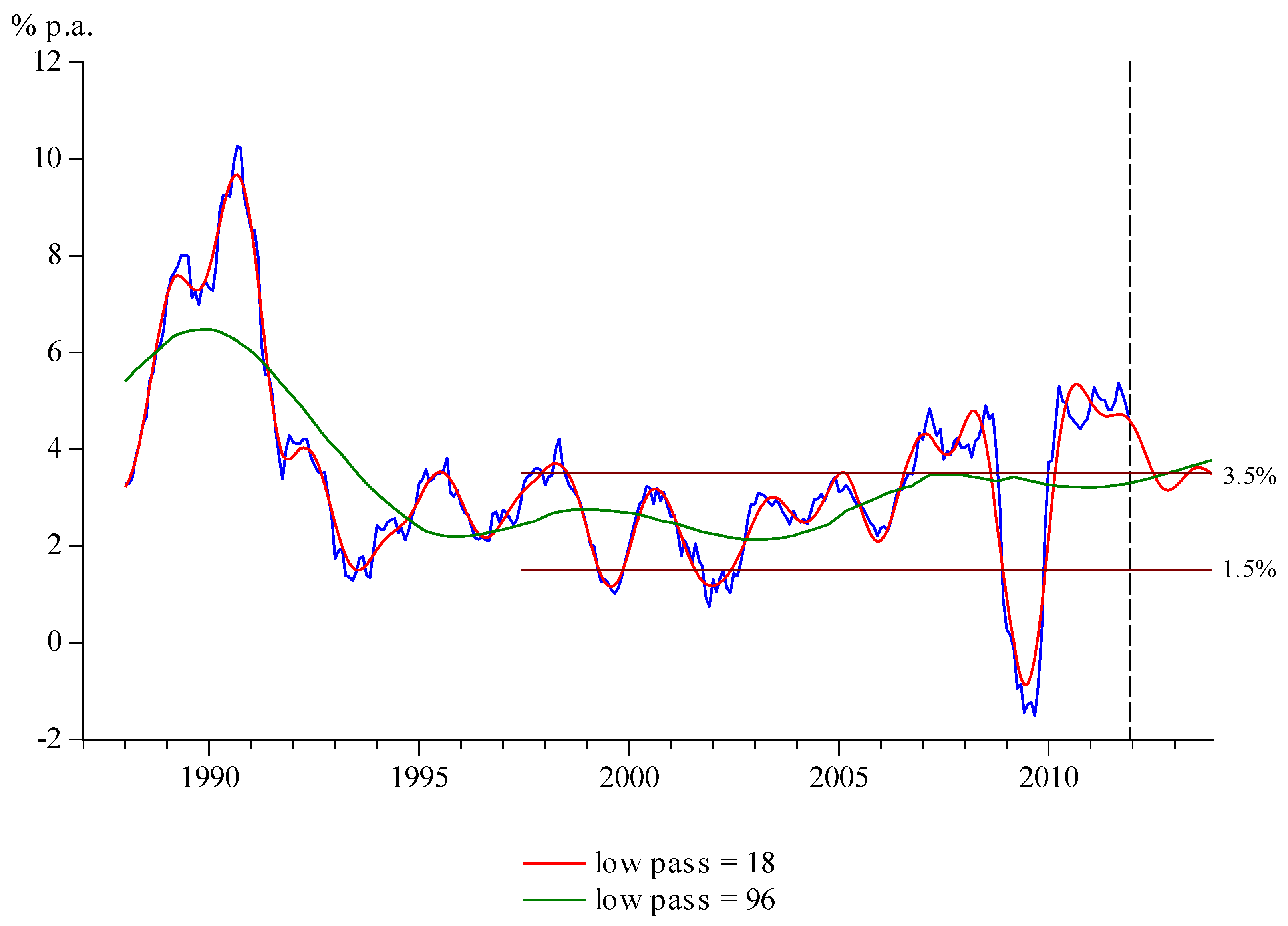

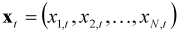

and 96 along with the observed inflation series calculated as

and 96 along with the observed inflation series calculated as  . Although this series is clearly not RPI inflation (the method of computing this in practice being much more detailed), the correlation between the two is in excess of 0.999 and plots of the two are indistinguishable from each other. With the lower setting of

. Although this series is clearly not RPI inflation (the method of computing this in practice being much more detailed), the correlation between the two is in excess of 0.999 and plots of the two are indistinguishable from each other. With the lower setting of  core inflation is essentially a smoothed version of actual inflation, but the higher setting produces a core inflation series that slowly varies through time: in fact, since the middle of 1993 it has consistently lain in the range 2 to

core inflation is essentially a smoothed version of actual inflation, but the higher setting produces a core inflation series that slowly varies through time: in fact, since the middle of 1993 it has consistently lain in the range 2 to  % per annum.

% per annum.  produced automatically by TRAMO using the models shown in Table 1. The expenditure weights used in the forecasts are held at their December 2011 values. Using forecasts of the trend-cycle components has the additional benefit of enabling the estimates of the trend components obtained from the low-pass filter to be computed with less error as the end of the sample is reached.

produced automatically by TRAMO using the models shown in Table 1. The expenditure weights used in the forecasts are held at their December 2011 values. Using forecasts of the trend-cycle components has the additional benefit of enabling the estimates of the trend components obtained from the low-pass filter to be computed with less error as the end of the sample is reached. target band for RPI inflation set on Bank of England independence in 1997.2 Core inflation for the setting

target band for RPI inflation set on Bank of England independence in 1997.2 Core inflation for the setting  is seen to have historically always lain within this band but is forecast to be 3.8% by the end of 2013, having breached the band in the middle of 2013. As has been mentioned above, setting

is seen to have historically always lain within this band but is forecast to be 3.8% by the end of 2013, having breached the band in the middle of 2013. As has been mentioned above, setting  , on the other hand, leads to much wider variation in core inflation with the bands being broken regularly from 2006, although this core inflation is forecast to be just under 3.5% by the end of 2013.

, on the other hand, leads to much wider variation in core inflation with the bands being broken regularly from 2006, although this core inflation is forecast to be just under 3.5% by the end of 2013.4. Alternative Weighting Schemes

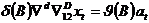

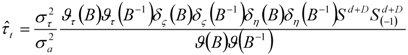

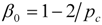

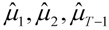

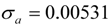

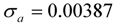

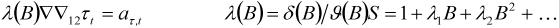

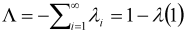

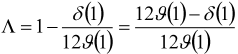

(the monthly change in the annual inflation rate of the trend-cycle component) is required. If the model for

(the monthly change in the annual inflation rate of the trend-cycle component) is required. If the model for  is of the form

is of the form

, which is the typical case from Table 1), then, on noting that

, which is the typical case from Table 1), then, on noting that  , we have

, we have

and noting that when

and noting that when  ,

,  , then

, then

so that

so that  and

and  . Four further sections have negative but finite persistence weights: food, household services, motoring and personal goods & services (household services and motoring have reduced form representations embodying stationary seasonality). As it is traditional in these cases to set the persistence weight to zero whenever

. Four further sections have negative but finite persistence weights: food, household services, motoring and personal goods & services (household services and motoring have reduced form representations embodying stationary seasonality). As it is traditional in these cases to set the persistence weight to zero whenever  , these six sections are thus assigned zero weights. For the two cases when

, these six sections are thus assigned zero weights. For the two cases when  (catering and leisure goods),

(catering and leisure goods),  , so that

, so that  and

and  .

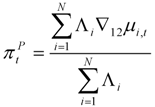

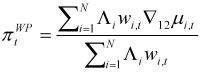

.  , may be used in two ways. First, they can replace the expenditure weights in (1) to produce the persistence weighted measure of core inflation (noting that in this application the weights remain constant through time)

, may be used in two ways. First, they can replace the expenditure weights in (1) to produce the persistence weighted measure of core inflation (noting that in this application the weights remain constant through time)

and

and  are thus akin to F&E (food and energy) exclusion-based measures of core inflation.

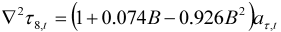

are thus akin to F&E (food and energy) exclusion-based measures of core inflation.| Section | Persistence weights |

|---|---|

| Alcohol | 0.094 |

| Catering | 1 |

| Cigarettes & tobacco | 0 (  ) ) |

| Clothing & footwear | 0.644 |

| Fares | 0.625 |

| Food | 0 (-0.812) |

| Fuel & light | 0 (  ) ) |

| Household goods | 0.437 |

| Household services | 0 (–1.133) |

| Housing | 0.536 |

| Leisure goods | 1 |

| Leisure services | 0.573 |

| Motoring | 0 (–2.042) |

| Personal goods & services | 0 (–0.344) |

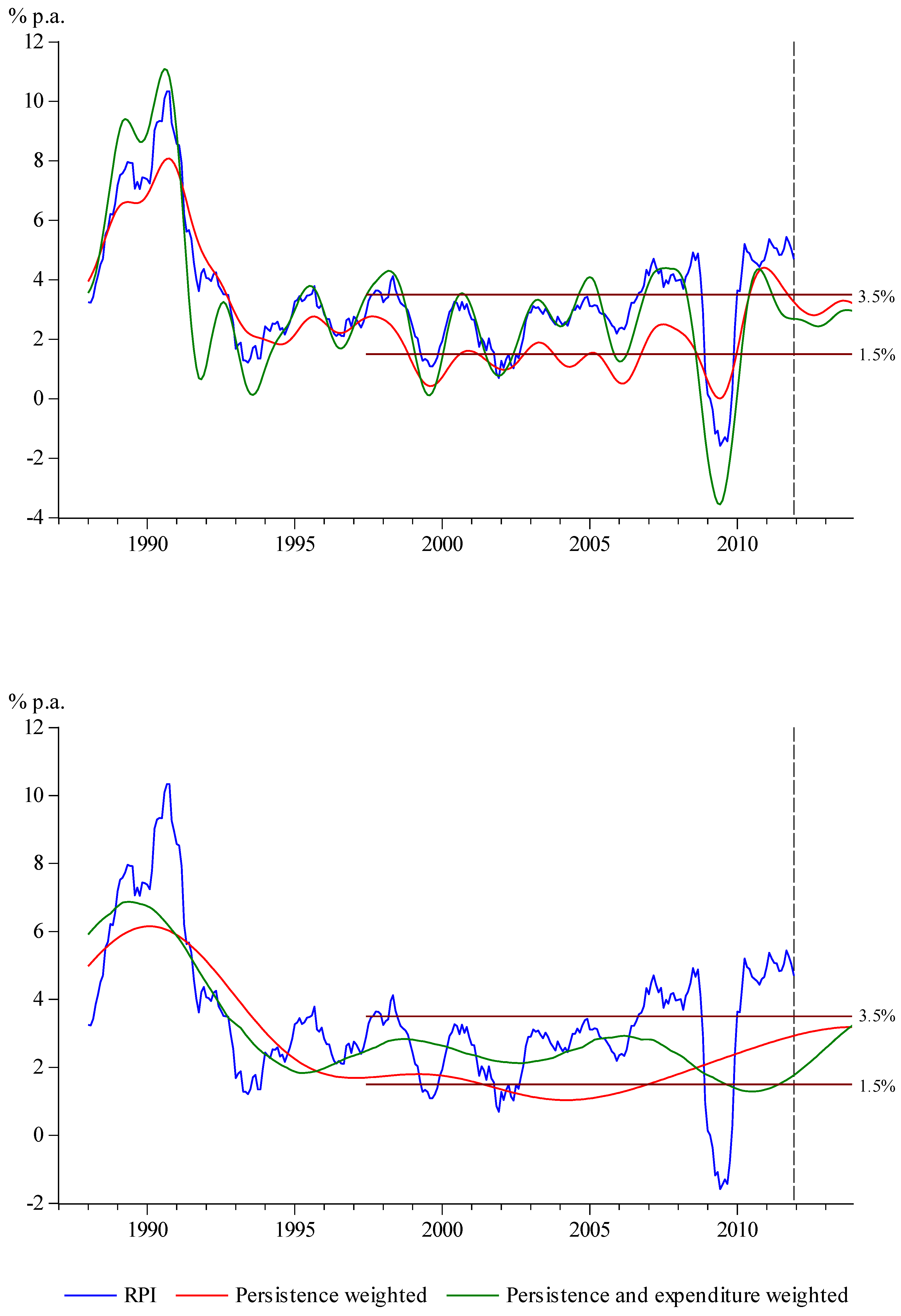

. These core inflations are rather more variable than those that use “simple” expenditure weights but again those using the frequency setting

. These core inflations are rather more variable than those that use “simple” expenditure weights but again those using the frequency setting  tend to lie within the

tend to lie within the  % band from 1998 and throughout the forecast period. Whether these core inflation estimates represent improvements over those computed in Section 3 is, however, debatable. The fixed weights used in

% band from 1998 and throughout the forecast period. Whether these core inflation estimates represent improvements over those computed in Section 3 is, however, debatable. The fixed weights used in  may be considered to be a drawback, which is only partially alleviated in

may be considered to be a drawback, which is only partially alleviated in  , while the exclusion of so many sections in both measures (six in all) may be felt to be too draconian. Nevertheless,

, while the exclusion of so many sections in both measures (six in all) may be felt to be too draconian. Nevertheless,  and

and  are easily computable and might be thought to provide useful additional information on core inflation.

are easily computable and might be thought to provide useful additional information on core inflation. 5. Multivariate Approaches to Constructing Core Inflation

and

and  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are defined analogously, the latter trio of disturbances being assumed to be mutually uncorrelated. The individual prices thus have potentially correlated stochastic trends having potentially correlated stochastic slopes. Given an appropriate vector or matrix of weights, a measure of core inflation can then be constructed using the estimated annual trend differences

are defined analogously, the latter trio of disturbances being assumed to be mutually uncorrelated. The individual prices thus have potentially correlated stochastic trends having potentially correlated stochastic slopes. Given an appropriate vector or matrix of weights, a measure of core inflation can then be constructed using the estimated annual trend differences  . This approach takes into account that individual prices might be contemporaneously correlated, but necessarily assumes that the individual prices all follow the same form of stochastic process. On examining Figure 1, this is clearly unlikely to be the case for the sections of the RPI and hence we do not investigate this model any further.

. This approach takes into account that individual prices might be contemporaneously correlated, but necessarily assumes that the individual prices all follow the same form of stochastic process. On examining Figure 1, this is clearly unlikely to be the case for the sections of the RPI and hence we do not investigate this model any further.6. Discussion and Conclusions

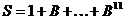

; bottom panel

; bottom panel  .

.

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- R.J. Gordon. “The impact of aggregate demand on prices.” Brookings Papers on Econ. Activ. 3 (1975): 613–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. Eckstein. Core Inflation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- A. Mankikar, and J. Paisley. Core Inflation: A Critical Guide. working paper No. 242; London, UK: Bank of England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- R. Rich, and C. Steindel. “A comparison of measures of core inflation.” Econ Pol Rev Dec 13 (2007): 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- M. Silver. Core Inflation: Measurement and Statistical Issues in Choosing Among Alternative Measures. IMF Staff papers 54; Washington, DC, USA: International Monetary Fund, 2007, pp. 163–190. [Google Scholar]

- M.A. Wynne. Core Inflation: A Review of Some Conceptual Issues. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 90; St. Louis, MO, USA: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, 2008, pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- D. Quah, and S.P. Vahey. “Measuring core inflation.” Econ. J. 105 (1995): 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Pedersen. “An alternative core inflation measure.” Ger. Econ. Rev. 10 (2009): 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.S. Blinder. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 79. Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 79; St. Louis, MO, USA: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, 1997, pp. 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- T. Cogley. “A simple adaptive measure of core inflation.” J. Money Credit Bank. 34 (2002): 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Gómez, and A. Maravall. Program SEATS “Signal Extraction in ARIMA Time Series” Instructions for the User. EUI working paper ECO no. 94/28; San Domenico di Fiesole, Italy: European University Institute, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- V. Gómez, and A. Maravall. Program TRAMO “Time Series Regression With ARIMA Noise, Missing Observations, and Outliers” Instructions for the User. EUI working paper ECO no. 94/31; San Domenico di Fiesole, Italy: European University Institute, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- R. Kaiser, and A. Maravall. “Combining filter design with model-based filtering (with an application to business-cycle estimation).” Int. J. Forecasting 21 (2005): 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.J. Hodrick, and E.C. Prescott. “Postwar U.S. business cycles: An empirical investigation.” J. Money Credit Bank. 29 (1997): 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Baxter, and R.G. King. “Measuring business cycles: Approximate band-pass filters for economic time series.” Rev. Econ. Stat. 81 (1999): 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.J. Christiano, and T.J. Fitzgerald. “The band pass filter.” Int. Econ. Rev. 44 (2003): 435–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS), Consumer Price Indices Technical Manual, 2010 Edition. Newport, UK: Office for National Statistics, 2010.

- J. Cutler. A New Measure of Core Inflation in the U.K. MPC unit discussion paper No. 3; London, UK: Bank of England, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- L. Bilke, and L. Stracca. “A persistence-weighted measure of core inflation in the Euro area.” Econ. Model. 24 (2007): 1032–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Proietti. “Measuring core inflation by multivariate structural time series models.” In Advances in Computational Economics, Finance and Management Science: Optimisation, Econometric and Financial Analysis. Edited by E.J. Kontoghiorghas and C. Gatu. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2007, pp. 205–223. [Google Scholar]

- J. Valle e Azevado. “A multivariate band-pass filter for economic time series.” J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 60 (2011): 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “EViews.” In EViews User Guide Version 7. Irvine, CA, USA: Quantitative Micro Software, 2009.

- 1These letters may be found at http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/inflation.htm

- 2The target was actually set for the RPIX (RPI excluding mortgage interest repayments) but we use the bounds here as a convenient reference point.

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Mills, T.C. Constructing U.K. Core Inflation. Econometrics 2013, 1, 32-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics1010032

Mills TC. Constructing U.K. Core Inflation. Econometrics. 2013; 1(1):32-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics1010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleMills, Terence C. 2013. "Constructing U.K. Core Inflation" Econometrics 1, no. 1: 32-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics1010032

APA StyleMills, T. C. (2013). Constructing U.K. Core Inflation. Econometrics, 1(1), 32-52. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics1010032