The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microgrid Components

2.1.1. PV Solar Panels

2.1.2. Wind Turbine

2.1.3. Electrolyser

2.1.4. PEM Fuel Cell

2.1.5. Compressed Hydrogen Storage Tank

- is the tank pressure ( Pa);

- is the number of moles contained in the tank (mol);

- is the tank volume ( m3);

- is the ideal gas constant (8.31 J/(mol·K));

- is the temperature of the gas contained in the tank (300 K).

- is the mass of the gas contained in the tank (kg);

- is the hydrogen molar mass (0.002 kg/mol).

- After substituting values, the mass contained in the tank can be obtained by Equation (3).

2.1.6. Lead–Acid Battery

2.2. Energy Management Strategy (EMS): Priority Based on Hydrogen or on Batteries

- : net available power (W); means energy deficit, while means energy excess;

- : power injected to the DC bus from PV and/or WT production (W); is always true;

- : power extracted from the DC bus due to load demand (W); is always true.

- : total microgrid power (W) understood as the power balance on the DC bus; of course, it must always be guaranteed that ;

- : power injected into or extracted from the main grid (W); if the power is extracted from the DC bus to be injected into the main grid, ; on the other hand, if the power is injected from the main grid to the DC bus, ;

- : power injected into or extracted from the hydrogen subsystem (W); if the power is extracted from the DC bus to supply the electrolyser, , while if the power is injected into the bus via the fuel cell, ;

- : power injected into or extracted from the battery bank (W); if power is extracted from the DC bus to recharge the battery bank, , while if power is injected into the DC bus from the battery bank, .

2.2.1. Hydrogen-Based Priority Strategy

2.2.2. Battery-Based Priority Strategy

3. Cost Analysis

3.1. Initial Investment Costs

3.2. Replacement Costs

- : number of operating cycles of the battery during one year (cycles/year);

- : sum of the energy used during a whole year to charge and discharge the battery (946.3 + 874.6 = 1820.9 kWh for the hydrogen-based priority EMS and 4127 + 3250 = 7377 kWh for the battery-based priority EMS);

- : maximum battery SOC (80%);

- : minimum battery SOC (20%);

- : maximum battery energy storage capacity (40.8 kWh).

- : stack fuel cell degradation (;

- : number of fuel cell starts (361 for hydrogen-based priority EMS and 60 for battery-based priority EMS);

- : number of fuel cell working hours (from Table 4: 2794.7 h for hydrogen-based priority EMS and 133.6 h for battery-based priority EMS).

3.3. Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Costs

3.4. Cost Savings and Energy Trading

3.5. Economic Analysis of the Microgrid

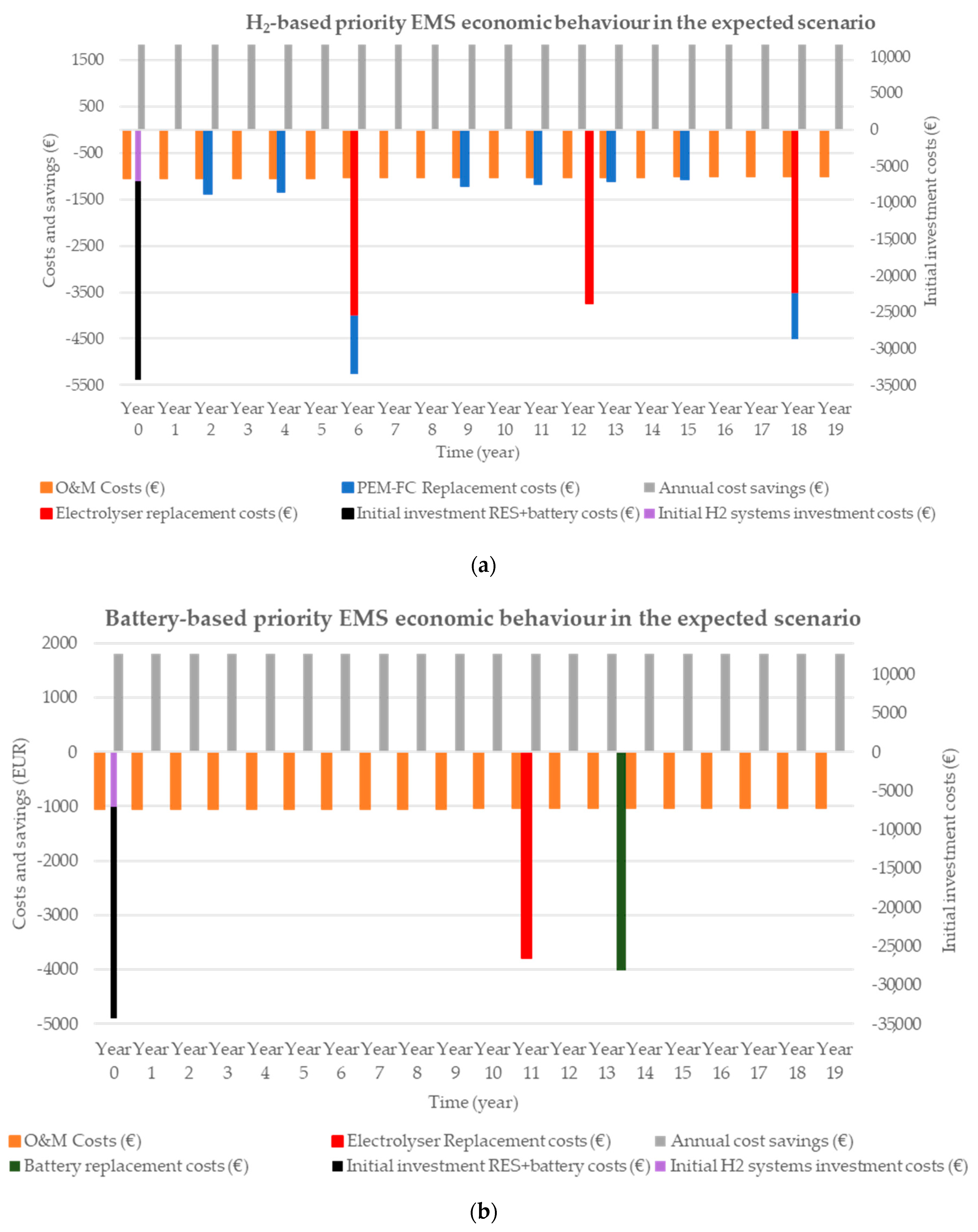

3.6. Expected Economic Scenario

4. Carbon Footprint Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The hydrogen-based priority strategy has the disadvantage of requiring a much higher investment (specifically EUR 74,177.4 vs. 17,537.88) and higher O&M costs (specifically EUR 35,254.03 vs. 34,877.08), and the advantage of higher annual cost savings (specifically, EUR 1837.65 vs. 1814.13).

- Hydrogen technologies are expected to become increasingly economically competitive, as a result of massive market demand and deployment, technological advances, process automation, increased component availability, economies of scale in the hydrogen industry, and increasing adoption of hydrogen technologies [34,35]. Just as, for example, wind power technology has experienced a dramatic cost reduction of more than 70% from the 1980s to the present day, hydrogen technologies are expected to follow a similar trend, meaning that the cost-effectiveness of a hydrogen-based microgrid could soon be a reality.

- A positive evolution of the lifespan of FCs, electrolysers, etc. is also expected, which implies that the main disadvantage of the hydrogen-based priority strategy, i.e., the number of equipment replacements required (with their associated costs), will be reduced in the near future, making this strategy much more cost-effective in the short term.

- The hydrogen-based priority EMS is more environmentally friendly than the battery-based priority EMS. Specifically, the hydrogen-based priority strategy leads to a carbon footprint, in absolute terms, of between 31.262 kg CO2 by 2021 and 35.728 kg CO2 by 2022, compared to the carbon footprint for the battery-based priority strategy of between 72.044 kg CO2 (2021) and 82.336 kg CO2 (2022).

- The continuing rise in CO2 emission costs means that the hydrogen-based priority EMS will not only be a more environmentally friendly option but will also result in an increase in annual cost savings compared to the battery-based priority EMS.

- The hydrogen-based priority EMS has greater independence from the main grid than the battery-based priority EMS (223.3 vs. 514.6 kWh taken from the main grid, respectively), which makes this strategy suitable for remote communities that do not have access to the main grid. Although this strategy could not completely eliminate the use of traditional diesel generators [38] in isolated grids as an element to guarantee electricity supply, it could drastically reduce their use.

- The higher equipment replacement and O&M costs for the hydrogen-based priority EMS over the lifespan of the microgrid are partially offset by the higher cost savings and associated lower carbon footprint, all in a scenario where hydrogen equipment costs are expected to decrease in the coming years [34,35]. Likewise, the costs of CO2 emissions will increase, which will make the hydrogen-based priority strategy increasingly competitive.

- A microgrid identical to the one studied (Figure 1) with only renewable generators (photovoltaic and wind), without energy storage, would obviously be much cheaper than the two modalities analysed in this article, even more so when compared to the hydrogen-based microgrid. The initial investment, and operation and maintenance costs, would be much lower (associated only with the purchase, operation, and maintenance of the renewable energy production equipment (see Table 3 and Table 7), respectively) and, in addition, there would be no associated replacement costs (except by accident, the renewable generation elements are not replaced during the lifespan of the microgrid). On the other hand, the carbon footprint would be considerably higher, as the main grid would have to compensate for the natural intermittency of renewable energy at any time (please, see Table 9).

- This article has demonstrated the advantages of hydrogen technologies in implementing reliable and clean microgrids, which are deeply respectful of the environment. However, economically speaking, they are not yet competitive. Therefore, the policy implications drawn from this work are the need for governments and companies to invest in research and development of hydrogen technologies so that costs can be drastically reduced. This looks set to be an accelerated path with no way back, as green hydrogen is now considered essential to address the increasingly necessary energy transition.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternate current |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditures |

| DC | Direct current |

| EMS | Energy management strategy |

| ESS | Energy storage system |

| FC | Fuel cell |

| HSS | Heat storage system |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| O&M | Operation and maintenance |

| PEM-FC | Proton exchange membrane fuel cell |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable energy sources |

| SMPC | Stochastic model predictive control |

| SOC | State of charge |

| WT | Wind turbine |

| Notation and Symbols | |

| Maximum electrolyser degradation (10,000 h) | |

| Fuel cell degradation () | |

| Maximum fuel cell degradation (100 mV/cell) | |

| Maximum battery energy storage capacity (40.8 kWh) | |

| Energy used during a whole year to charge and discharge the battery (kWh) | |

| Mass of the gas contained in the tank (kg) | |

| Molar mass (kg/mol) | |

| Hydrogen molar mass (kg/mol) | |

| Number of fuel cell working hours (h) | |

| Number of fuel cell starts (starts) | |

| Number of moles contained in the tank (mol) | |

| Number of operating cycles of the battery during one year (cycles/year) | |

| Power injected or extracted from the battery system (W) | |

| Power extracted from the DC bus to be injected into the battery (W) | |

| Power injected into the DC bus via battery (W) | |

| Power extracted from the DC bus to be injected into the electrolyser (W) | |

| Power injected into the bus via fuel cell (W) | |

| Power injected or extracted from the main grid (W) | |

| Power injected from the main grid to the DC bus (W) | |

| Power extracted from the DC bus to be injected into the main grid (W) | |

| Power injected or extracted from the hydrogen systems (W) | |

| Load power (W) | |

| Net power (W) | |

| RES power (W) | |

| Hydrogen tank pressure (Pa) | |

| Maximum hydrogen tank pressure (30 bar) | |

| Minimum hydrogen tank pressure (1 bar) | |

| Ideal gas constant (8.31 J/(K·mol)) | |

| Battery state of charge (Ah, %) | |

| Maximum state of charge (Ah, 80%) | |

| Minimum state of charge (Ah, 20%) | |

| Temperature of the gas contained in the tank (K) | |

| Hydrogen tank volume (m3) | |

References

- World Bank. The World Bank Annual Report 2018; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, K.; Jiang, Q. Assessing energy vulnerability and its impact on carbon emissions: A global case. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, M.; Shaffer, B. Paying for performance: The role of policy in energy storage deployment. Energy Econ. 2020, 92, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Kamwa, I.; Moeini, A.; Mohseni-Bonab, S.M. Energy management in microgrids using transactive energy control concept under high penetration of Renewables; A survey and case study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, M.; AlJaberi, N.S.A.M.; Al Qaydi, N.A.S.M. Solar-hydrogen microgrid project. In Proceedings of the SEG/AAPG/EAGE/SPE Research and Development Petroleum Conference and Exhibition 2018, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–10 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzis, A.; Ziogou, C.; Panopoulos, K.D.; Papadopoulou, S.; Seferlis, P.; Voutetakis, S. Energy management strategies based on hybrid automata for islanded microgrids with renewable sources, batteries and hydrogen. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.T.; Ma, C.Q.; Mirza, N.; Ren, Y.S.; Narayan, S.W.; Chen, X.Q. A renewable energy microgrids trading management platform based on permissioned blockchain. Energy Econ. 2022, 115, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to 2030; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Uresti, S.I.; Martín, M.; Jiménez-Gutiérrez, A. A Methodology for the Design of Flexible Renewable-Based Utility Plants. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 4580–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilich, A.; Langham, K.; Geyer, R.; Goyal, L.; Hansen, J.; Krishnan, A.; Bergesen, J.; Sinha, P. Life cycle assessment of solar photovoltaic microgrid systems in off-grid communities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Cortés, L.F.; Ortega-Quintanilla, M.; Flores-Tlacuahuac, A. Water-Energy Off-Grid Systems Design Using a Dominant Stakeholder Approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8554–8578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforti Ferrario, A.; Bartolini, A.; Segura Manzano, F.; Vivas, F.J.; Comodi, G.; McPhail, S.J.; Andujar, J.M. A model-based parametric and optimal sizing of a battery/hydrogen storage of a real hybrid microgrid supplying a residential load: Towards island operation. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 3, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahant, B.; Linga, P.; Kumar, R. Hydrogen Economy and Role of Hythane as a Bridging Solution: A Perspective Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 15424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balat, M. Potential importance of hydrogen as a future solution to environmental and transportation problems. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 4013–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, A.M.; Vivas, F.J.; Manzano, F.S.; Andújar, J.M.; Bocci, E.; Martirano, L. Hydrogen vs. Battery in the long-term operation. A comparative between energy management strategies for hybrid renewable microgrids. Electronics 2020, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Olivier, J.C.; Auger, F.; Auvity, B.; Schaeffer, E.; Bourguet, S.; Schiebel, J.; Perret, J. A combined optimization of the sizing and the energy management of an industrial multi-energy microgrid: Application to a harbour area. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 12, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, J. Sizing versus Price: How they influence the energy exchange among large numbers of hydrogen-centric multi-energy supply grid-connected microgrids. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Stadler, M.; Auer, H.; Zellinger, M. Advanced optimal planning for microgrid technologies including hydrogen and mobility at a real microgrid testbed. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 19285–19302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming Kwok, J.J.; Yu, N.; Karimi, I.A.; Lee, D.Y. Microgrid scheduling for reliable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly energy management. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, H.; Lyu, C.; Xie, P.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Y. A hybrid model of energy scheduling for integrated multi-energy microgrid with hydrogen and heat storage system. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobajas, J.; Garcia-Torres, F.; Roncero-Sánchez, P.; Vázquez, J.; Bellatreche, L.; Nieto, E. Resilience-oriented schedule of microgrids with hybrid energy storage system using model predictive control. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 118092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ueda, Y.; Sugiyama, M. Greedy energy management strategy and sizing method for a stand-alone microgrid with hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Weng, Z.; Zheng, H. Optimal Operation of a Microgrid with Hydrogen Storage Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, F.J.; De las Heras, A.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. A review of energy management strategies for renewable hybrid energy systems with hydrogen backup. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 126–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, F.J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M. Fuzzy logic-based energy management system for grid-connected residential DC microgrids with multi-stack fuel cell systems: A multi-objective approach. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas Fernández, F.J.; Manzano, F.S.; Márquez, J.M.A.; Calderón Godoy, A.J. Extended Model Predictive Controller to Develop Energy Management Systems in Renewable Source-Based Smart Microgrids with Hydrogen as Backup. Theoretical Foundation and Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andújar, J.M.; Vivas, F.J.; Segura, F.; Calderón, A.J. Integration of air-cooled multi-stack polymer electrolyte fuel cell systems into renewable microgrids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 142, 108305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, A.; Heffel, J.; Messer, C. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Engines and Related Technologies—Module 1: Hydrogen Properties. 2001. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/14966 (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Woody, A.I. How is the Ideal Gas Law Explanatory? Sci. Educ. 2013, 22, 1563–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2019; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vivas, F.J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Caparrós, J.J. A suitable state-space model for renewable source-based microgrids with hydrogen as backup for the design of energy management systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 219, 113053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andújar, J.M.; Segura, F.; Rey, J.; Vivas, F.J. Batteries and Hydrogen Storage: Technical Analysis and Commercial Revision to Select the Best Option. Energies 2022, 15, 6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard Power Systems. Putting Fuel Cells to Work: FCgen®-1020ACS Fuel Cell Stack FCvelocity®-1020ACS Fuel Cell Stack; Product Manual and Integration Guide; Ballard Power Systems Inc.: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2016; pp. 5127049–5127063. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the 1.5 °C Climate Goal; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogen Council. Path to Hydrogen Competitiveness: A Cost Perspective; Hydrogen Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- REData. Emisiones y Factor de Emisión de CO2 eq. de la Generación. Red Eléctrica. Available online: https://www.ree.es/es/datos/generacion/no-renovables-detalle-emisiones-CO2 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2021; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustayen, A.G.M.B.; Rasul, M.G.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M.; Hamilton, J.M. Remote areas and islands power generation: A review on diesel engine performance and emission improvement techniques. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 260, 115614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Investment Costs | O&M Costs | Replacement Costs as a Function of EMS | Annual Profits | CO2 Footprint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Yes | Yes | No * | Yes | No |

| [17] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| [18] | Yes | Yes | No * | No | Yes |

| [19] | No | Yes | No | Yes | No ** |

| [20] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| [21] | No | Yes | No * | No | No |

| [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| [23] | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Author’s proposal | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Element | Parameters | Model |

|---|---|---|

| Lead–acid battery | 100 Ah (40.8 kWh) | U-Power® UP100-12 |

| Electrolyser | 10 kWe | H2 Nitidor® 0074-01-PMO-001 |

| H2 tank | 30 bar, 1.044 m3, 2.51 kg H2 (300 K) | Lapesa® LSP1000H |

| PEM FC | 3.4 kWe | Ballard® FCgen 1020ACS |

| Wind turbine | 3 kWp | Enair® E-30PRO |

| Solar PV mono-Si-based panels | 5 kWp | Isofoton® ISF-250 |

| Solar PV poly-Si-based panels | 5 kWp | Atersa® A-230P |

| Solar PV thin-film a-Si-based panels | 5 kWp | Schott® ASI 100 |

| Element | Units | CAPEX | Total Cost (2022) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead–acid battery | 40.8 kWh | 200 EUR/kWh [12] | EUR 8160 |

| Electrolyser | 10 kW | 1500 EUR/kW [12] | EUR 15,000 |

| H2 tank | 2.51 kg | 2000 EUR/kg [12] | EUR 5025.27 |

| PEM FC | 3.4 kW | 1500 EUR/kW [12] | EUR 5100 |

| Wind turbine (1) | 3 kW | 1303.54 EUR/kW [30] | EUR 3519.56 |

| PV panels (1) | 15 kW | 1247.79 EUR/kW [30] | EUR 15,534.96 |

| Total initial microgrid investments | EUR 52,339.78 | ||

| Element | Hydrogen-Based Priority EMS | Battery-Based Priority EMS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours | Energy (kWh) | Hours | Energy (kWh) | |

| Lead–acid battery charge | 1131 h | 946.3 | 2797 h | 4127 |

| Lead–acid battery discharge | 668.1 h | 874.6 | 3115 h | 3250 |

| Electrolyser | 1618.4 h | 5967 | 846.1 h | 927.6 |

| PEM FC | 2794.7 h | 2842 | 133.6 h | 175.2 |

| H2-Based Priority EMS | Battery-Based Priority EMS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Maximum Element Degradation | Annual Degradation | Replacement Frequency (Years) | Number of Replacements (in 20 Years) | Annual Degradation | Replacement Frequency (Years) | Number of Replacements (in 20 Years) |

| Battery bank | 1500 cycles [32] | 26.8 cycles | >20 | 0 | 108.5 cycles | 13.83 | 1 |

| Electrolyser | 10,000 h [31] | 1617.8 h | 6.18 | 3 | 846.1 h | 11.82 | 1 |

| Fuel cell | 8000 mV/stack [33] | 3549.28 mV/stack | 2.25 | 8 | 272.24 mV/stack | >20 | 0 |

| Hydrogen-Based Priority EMS | Battery-Based Priority EMS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Initial Costs (EUR) (1) | Cost Reduction over a Decade (%) | Annual Cost Reduction (%) (2) | Number of Replacements (in 20 Years) | Replacements Costs (EUR) (3) | Number of Replacements (in 20 Years) | Replacements Costs (EUR) (3) |

| Battery bank | 8160 | 39 [35] | 3.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4022.88 |

| Electrolyser | 15,000 | 9 [34] | 0.9 | 3 | 40,140 | 1 | 13,515 |

| Fuel cell | 5100 | 17 [35] | 1.7 | 8 | 34,037.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Total replacement costs (EUR) | 74,177.4 | 17,537.88 | |||||

| Element | Units | Initial Costs (EUR) (1) | O&M Costs | Total O&M Costs (EUR/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battery bank | 40.8 kWh | 8160 | 5% CAPEX/y [12] | EUR 408 |

| Electrolyser | 10 kW | 15,000 | 5% CAPEX/y [12] | EUR 750 |

| H2 tank | 2.51 kg | 5025.27 | 2% CAPEX/y [12] | EUR 100.51 |

| Fuel cell | 3.4 kW | 5100 | 5% CAPEX/y [12] | EUR 255 |

| Wind turbine | 3 kW | 3519.56 | 29.20 EUR/kW [30] | EUR 87.60 |

| PV panels | 15 kW | 15,534.96 | 16.37 EUR/kW [30] | EUR 245.55 |

| Total initial annual O&M costs of microgrid | EUR 1849.67 | |||

| Year | O&M Costs (EUR/Year) Hydrogen-Based Priority EMS | O&M Costs (EUR/Year) Battery-Based Priority EMS |

|---|---|---|

| Years 0–1 | 1849.67 | 1849.67 |

| Years 2–3 | 1841.00 | 1849.67 |

| Years 4–5 | 1832.33 | 1849.67 |

| Years 6–8 | 1783.16 | 1849.67 |

| Years 9–10 | 1770.15 | 1849.67 |

| Year 11 | 1761.48 | 1775.42 |

| Year 12 | 1720.98 | 1775.42 |

| Years 13–14 | 1712.31 | 1568.56 |

| Years 15–17 | 1703.64 | 1568.56 |

| Years 18–19 | 1650.14 | 1568.56 |

| Total O&M costs during the lifespan of the microgrid (EUR) | 35,254.03 | 34,877.08 |

| Hydrogen-Based Priority EMS | Battery-Based Priority EMS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Costs (EUR/kWh) | Energy (kWh) (1) | Savings (EUR) | Energy (kWh) (1) | Savings (EUR) | |

| Load demand | - | 12,050 | - | 12,050 | - |

| Battery bank discharge | 0.136 [12] | 874.6 | 118.95 | 3250 | 442.00 |

| Fuel cell | 0.136 [12] | 2842 | 386.51 | 175.2 | 23.83 |

| Grid in | −0.136 [12] | 223.3 | −30.37 | 514.6 | −69.99 |

| RES | 0.136 [12] | 8110.1 | 1102.96 | 8110.2 | 1100.51 |

| Grid out | 0.03 [12] | 8653 | 259.59 | 10,510 | 315.3 |

| Total annual savings | 1837.65 | 1814.13 | |||

| H2-Based Priority EMS | Battery-Based Priority EMS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial investment costs (EUR) | EUR 52,339.78 | ||

| O&M costs (EUR) | Annual average | EUR 1762.70 | EUR 1743.85 |

| Total (20 years) | EUR 35,254.03 | EUR 34,877.08 | |

| Replacement costs (EUR) | Total (20 years) | EUR 74,177.40 | EUR 17,537.88 |

| Cost savings (EUR) | Annual | EUR 1837.65 | EUR 1814.13 |

| Total (20 years) | EUR 36,753.05 | EUR 36,282.58 | |

| Current Scenario | Target Scenario | Total Cost Reduction Needed to Achieve the Target Scenario (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial invest. costs (EUR) | 52,339.78 | FC: 5100 | 34,249.59 | FC: 1428 | 34.56 |

| TANK: 5025.27 | TANK: 1407.08 | ||||

| ELECTROLYSER: 15,000 | ELECTROLYSER: 4200 | ||||

| BATT: 8160 | BATT: 8160 | ||||

| PV: 15,534.96 | PV: 15,534.96 | ||||

| WT: 3519.56 | WT: 3519.56 | ||||

| Initial annual O&M costs (EUR) | 1849.67 | FC: 255 | 1053.70 | FC: 71.4 | 43.03 |

| TANK: 100.51 | TANK: 28.14 | ||||

| ELECTROLYSER: 750 | ELECTROLYSER: 210 | ||||

| BATT: 408 | BATT: 408 | ||||

| PV: 247.77 | PV: 247.77 | ||||

| WT: 88.39 | WT: 88.39 | ||||

| EMS | Consumption (kWh) | Spanish Electricity Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2020 [36] | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2020 | % CO2 Savings 2020 | Spanish Electricity Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2021 [36] | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2021 | % CO2 Savings 2021 | Spanish Electricity Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2022 [36] | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2022 | % CO2 Savings 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microgrid with hydrogen-based priority | 223.3 | 0.15 | 33.495 | 98.15 | 0.14 | 31.262 | 98.15 | 0.16 | 35.728 | 98.15 |

| Microgrid with battery-based priority | 514.6 | 0.15 | 77.19 | 95.73 | 0.14 | 72.044 | 95.73 | 0.16 | 82.336 | 95.73 |

| Traditional connection to the main electrical grid | 12,050 | 0.15 | 1807.5 | - | 0.14 | 1687 | - | 0.16 | 1928 | - |

| Application | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2020 | CO2 Emission Costs 2020 (EUR) | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2021 | CO2 Emission Costs 2021 (EUR) | Carbon Footprint (kg CO2) Year 2022 | CO2 Emission Costs 2022 (EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-based priority | 33.495 | 1.19–2.37 | 31.262 | 1.11–2.21 | 35.728 | 1.26–2.53 |

| Battery-based priority | 77.19 | 2.73–5.47 | 72.044 | 2.55–5.10 | 82.336 | 2.91–5.83 |

| Loads connected to the electrical grid | 1807.5 | 63.99–127.97 | 1687 | 59.72–119.44 | 1928 | 68.25–136.50 |

| H2-Based Priority | Battery-Based Priority | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Investment Costs (EUR) (1) | Energy (kWh) (2) | Unitary Costs (EUR/kWh) | Investment Costs (EUR) (1) | Energy (kWh) (2) | Unitary Costs (EUR/kWh) |

| RES | 19,054.52 | 162,202 | 0.117 | 19,054.52 | 162,202 | 0.117 |

| ALKEL | 55140 | 119,340 | 0.462 | 28515 | 18,552 | 1.537 |

| PEM-FC | 39,137.4 | 56,840 | 0.689 | 5100 | 3504 | 1.455 |

| Battery | 8160 | 17,492 | 0.466 | 12,182.88 | 65,000 | 0.187 |

| H2 tank | 5025.27 | 72,385 (3) | 0.069 | 5025.27 | 11,253 (3) | 0.447 |

| Total | 126,517.19 | 428,259 | 0.295 | 69,877.67 | 260,511 | 0.268 |

| H2-Based Priority | Battery-Based Priority | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | O&M Costs (EUR) (1) | Energy (kWh) (2) | Unitary Costs (EUR/kWh) | O&M Costs (EUR) (1) | Energy (kWh) (2) | Unitary Costs (EUR/kWh) |

| RES | 6663 | 162,202 | 0.041 | 6663 | 162,202 | 0.041 |

| ALKEL | 14,028 | 119,340 | 0.118 | 14,331.75 | 18,552 | 0.773 |

| PEM-FC | 4332.705 | 56,840 | 0.076 | 5100 | 3504 | 1.455 |

| Battery | 8160 | 17,492 | 0.466 | 6712.01 | 65,000 | 0.103 |

| H2 tank | 2010.2 | 72,385 (3) | 0.028 | 5025.27 | 1253 (3) | 0.447 |

| Total | 35,193.905 | 428,259 | 0.082 | 37,832.03 | 260,511 | 0.145 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rey, J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ferrario, A.M. The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids. Electronics 2023, 12, 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12173703

Rey J, Segura F, Andújar JM, Ferrario AM. The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids. Electronics. 2023; 12(17):3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12173703

Chicago/Turabian StyleRey, Jesús, Francisca Segura, José Manuel Andújar, and Andrea Monforti Ferrario. 2023. "The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids" Electronics 12, no. 17: 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12173703

APA StyleRey, J., Segura, F., Andújar, J. M., & Ferrario, A. M. (2023). The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids. Electronics, 12(17), 3703. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12173703