Electrospinning of Nanofibers for Energy Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

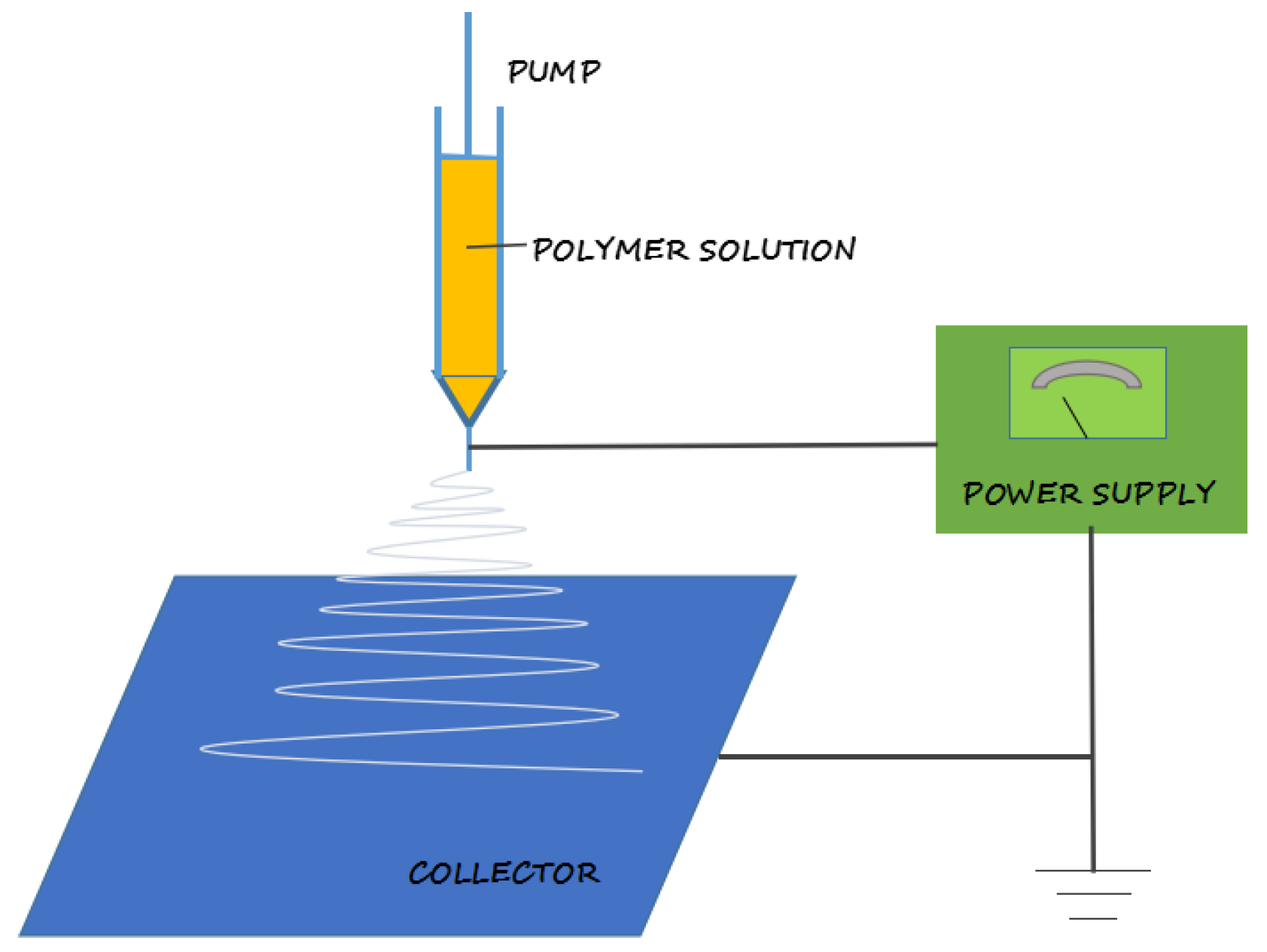

2. Electrospinning

3. Applications

3.1. Lithium-Based Batteries

3.1.1. Li-Ion Batteries

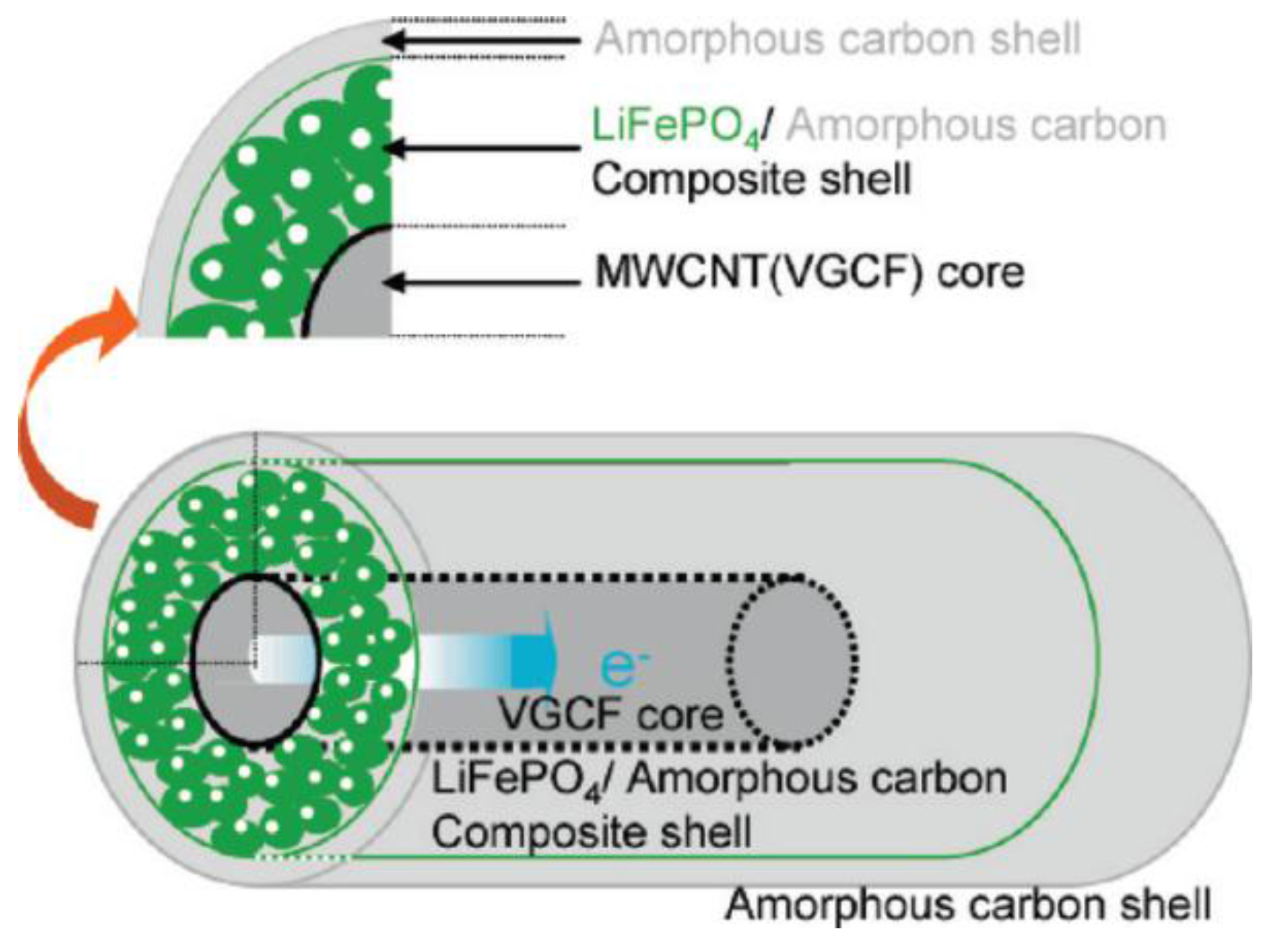

3.1.1.1. Cathode Materials

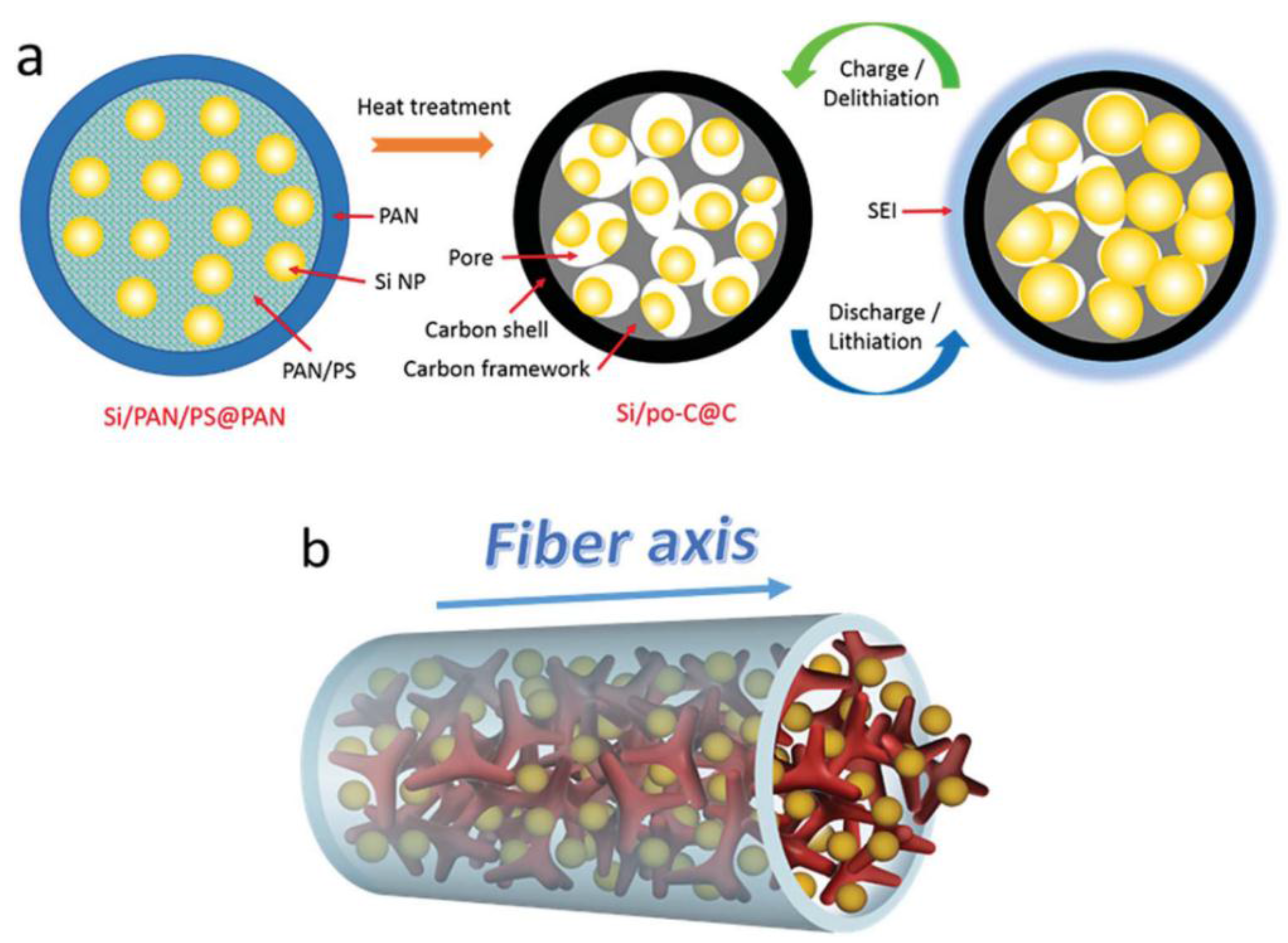

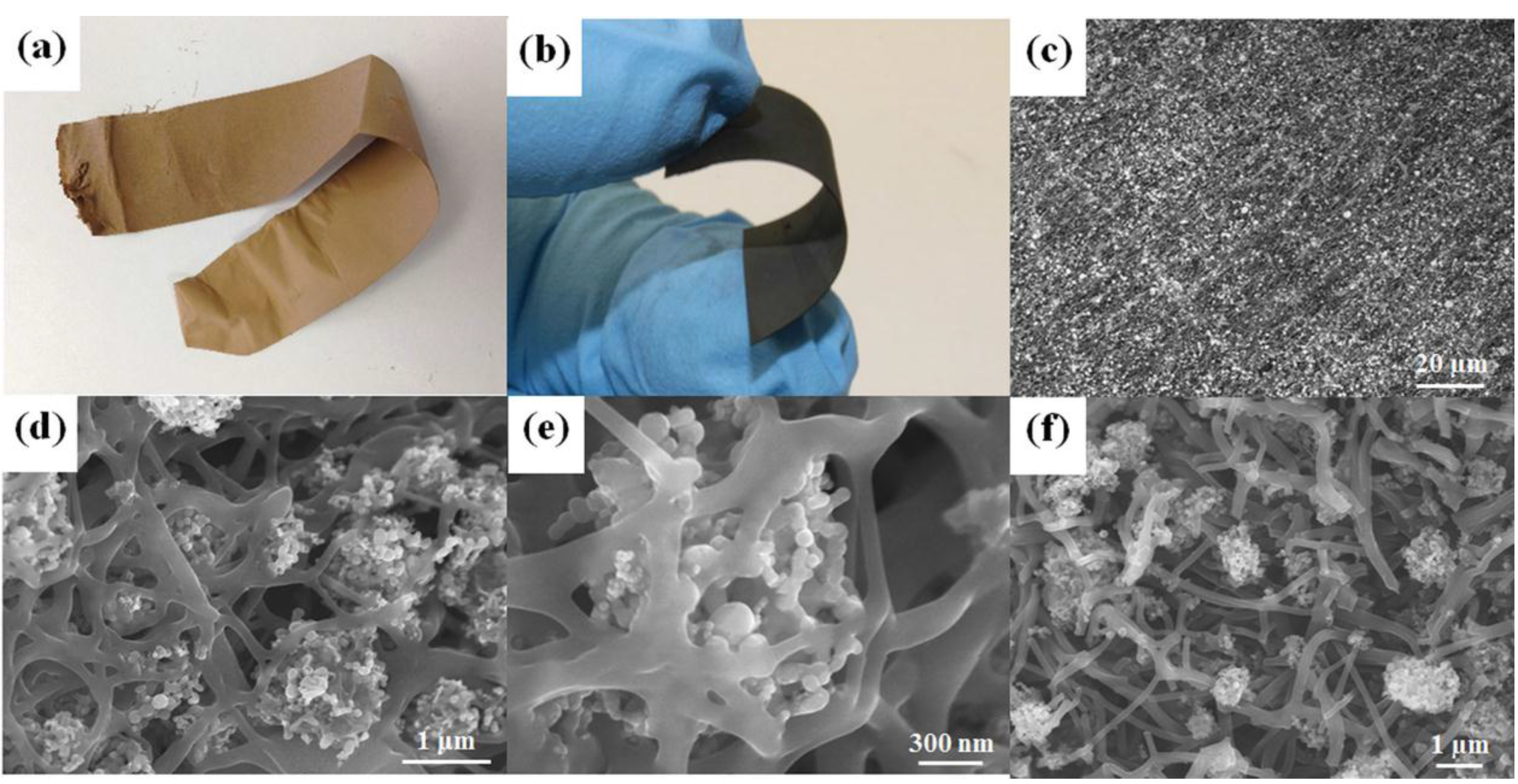

3.1.1.2. Anode Materials

3.1.1.3. Separator Materials

3.1.2. Li-S and Li-O2 Batteries

3.1.2.1. Li-S Batteries

3.1.2.2. Lithium-O2 Batteries

3.2. Fuel Cells

3.2.1. Electrode Materials

3.2.2. Electrolyte Membrane

3.3. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells

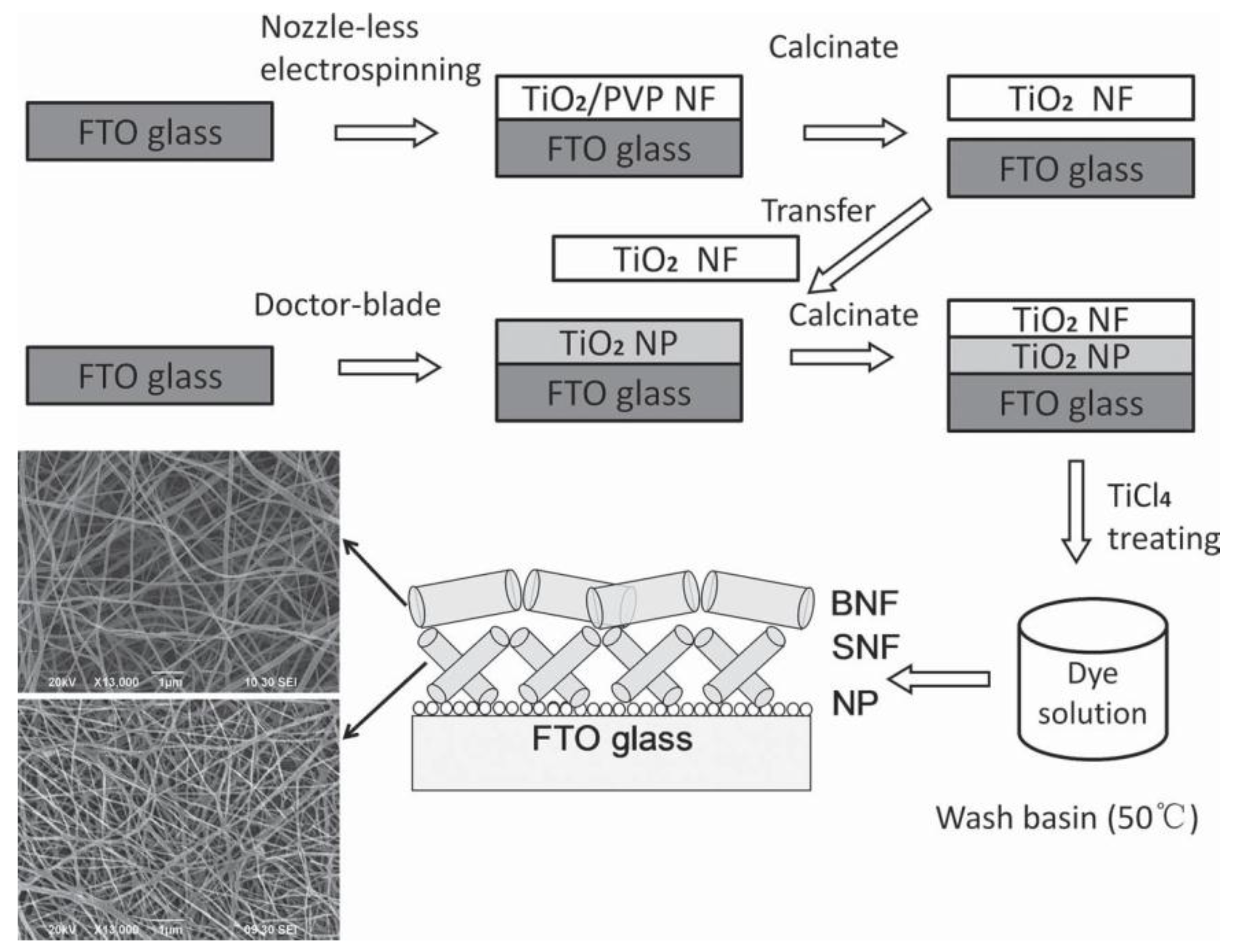

3.3.1. Photoanode

3.3.2. Counter Electrodes

3.3.3. Electrolytes of DSSCs

3.4. Supercapacitors

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, M.; Wu, X.; Zeng, J.; Hou, Z.; Liao, S. Heteroatom Doped Carbon Nanofibers Synthesized by Chemical Vapor Deposition as Platinum Electrocatalyst Supports for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 182, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balde, C.P.; Hereijgers, B.P.; Bitter, J.H.; Jong, K.P. Sodium Alanate Nanoparticles-Linking Size to Hydrogen Storage Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6761–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.D.; Walker, L.S.; Hadjiev, V.G.; Khabashesku, V.; Corral, E.L.; Krishnamoorti, R.; Cinibulk, M. Fast Sol-Gel Preparation of Silicon Carbide-Silicon Oxycarbide Nanocomposites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 4444–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, J. Cellulose-Rich Nanofiber-Based Functional Nanoarchitectures. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1143–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.; Beichen, Z.; Nicholette, L.J.E.; Kaimeng, Z.; Chowdari, B. Molten salt synthesis and its electrochemical characterization of Co3O4 for lithium batteries. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2011, 14, A79–A82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Yu, C.; Jiahuan, F.; Loh, K.P.; Chowdari, B. Molten salt synthesis and energy storage studies on CuCo2O4 and CuO·Co3O4. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 9619–9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Khai, V.; Chowdari, B. Facile one pot molten salt synthesis of nano (M1/2Sb1/2Sn)O4 (M = V, Fe, In). Mater. Lett. 2015, 140, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Reddy, M.; Chowdari, B.; Ramakrishna, S. Long-term cycling studies on electrospun carbon nanofibers as anode material for lithium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 12175–12184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.; Quan, C.Y.; Teo, K.W.; Ho, L.J.; Chowdari, B. Mixed Oxides,(Ni1 − xZnx) Fe2O4 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1): Molten Salt Synthesis, Characterization and Its Lithium-Storage Performance for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 4709–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Cherian, C.T.; Ramanathan, K.; Jie, K.C.W.; Daryl, T.Y.W.; Hao, T.Y.; Adams, S.; Loh, K.; Chowdari, B. Molten synthesis of ZnO. Fe3O4 and Fe2O3 and its electrochemical performance. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 118, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Sharma, N.; Adams, S.; Rao, R.P.; Peterson, V.K.; Chowdari, B. Evaluation of undoped and M-doped TiO2, where M = Sn, Fe, Ni/Nb, Zr, V, and Mn, for lithium-ion battery applications prepared by the molten-salt method. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 29535–29544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Teoh, X.V.; Nguyen, T.; Lim, Y.M.; Chowdari, B. Effect of 0.5 M NaNO3: 0.5 M KNO3 and 0.88 M LiNO3: 0.12 M LiCl molten salts, and heat treatment on electrochemical properties of TiO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, A762–A769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithyadharseni, P.; Reddy, M.; Ozoemena, K.I.; Balakrishna, R.G.; Chowdari, B. Low temperature molten salt synthesis of Y2Sn2O7 anode material for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 182, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Tung, B.D.; Yang, L.; Minh, N.D.Q.; Loh, K.; Chowdari, B. Molten salt method of preparation and cathodic studies on layered-cathode materials Li(Co0.7Ni0.3)O2 and Li(Ni0.7Co0.3)O2 for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 225, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Beichen, Z.; Loh, K.; Chowdari, B. Facile synthesis of Co3O4 by molten salt method and its Li-storage performance. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 3568–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Rao, G.S.; Chowdari, B. Synthesis and electrochemical studies of the 4 V cathode, Li(Ni2/3Mn1/3)O2. J. Power Sources 2006, 160, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Jie, T.W.; Jafta, C.J.; Ozoemena, K.I.; Mathe, M.K.; Nair, A.S.; Peng, S.S.; Idris, M.S.; Balakrishna, G.; Ezema, F.I. Studies on Bare and Mg-doped LiCoO2 as a cathode material for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 128, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakunthala, A.; Reddy, M.; Selvasekarapandian, S.; Chowdari, B.; Selvin, P.C. Synthesis of compounds, Li(MMn11/6)O4 (M = Mn1/6, Co1/6, (Co1/12Cr1/12), (Co1/12Al1/12), (Cr1/12Al1/12)) by polymer precursor method and its electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 4441–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Sakunthala, A.; SelvashekaraPandian, S.; Chowdari, B. Preparation, Comparative Energy Storage Properties, and Impedance Spectroscopy Studies of Environmentally Friendly Cathode, Li(MMn11/6)O4 (M = Mn1/6, Co1/6, (Co1/12Cr1/12)). J. Physi. Chem. C 2013, 117, 9056–9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabu, M.; Reddy, M.; Selvasekarapandian, S.; Rao, G.S.; Chowdari, B. (Li, Al)-co-doped spinel, Li(Li0.1Al0.1Mn1.8)O4 as high performance cathode for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 88, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Reddy, M.; Liu, H.; Ramakrishna, S.; Rao, G.S.; Chowdari, B. Nano LiMn2O4 with spherical morphology synthesized by a molten salt method as cathodes for lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 7462–7469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Raju, M.S.; Sharma, N.; Quan, P.; Nowshad, S.H.; Emmanuel, H.-C.; Peterson, V.; Chowdari, B. Preparation of Li1.03Mn1.97O4 and Li1.06Mn1.94O4 by the Polymer Precursor Method and X-ray, Neutron Diffraction and Electrochemical Studies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A1231–A1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Cheng, H.; Tham, J.; Yuan, C.; Goh, H.; Chowdari, B. Preparation of Li(Ni0.5Mn1.5)O4 by polymer precursor method and its electrochemical properties. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 62, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Song, L.; Xiong, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Xi, Z.; Jin, D.; Chen, J. TiO2/Nb2O5 core-sheath nanofibers film: Co-electrospinning fabrication and its application in dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 25, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Deng, Y.; Liang, K.; Liu, X.; Hu, W. LaNiO3/NiO hollow nanofibers with mesoporous wall: A significant improvement in NiO electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014, 19, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xiao, W.; Yu, J. High-efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells based on electrospun TiO2 multi-layered composite film photoanodes. Energy 2015, 86, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Yang, K.S.; Woo, H.G.; Oshida, K. Supercapacitor performance of porous carbon nanofiber composites prepared by electrospinning polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS)/polyacrylonitrile (PAN) blend solutions. Synth. Met. 2011, 161, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, L. Electrospinning of multilevel structured functional micro-/nanofibers and their applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 7290–7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.G.; Yuan, S.; Ma, D.L.; Zhang, X.B.; Yan, J.M. Electrospun materials for lithium and sodium rechargeable batteries: From structure evolution to electrochemical performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1660–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Yang, Y.; Kang, F. Carbon nanofibers prepared via electrospinning. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2547–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.L.; Yu, S.H. Nanoparticles meet electrospinning: Recent advances and future prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4423–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Kang, F.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Kim, J.-K. Recent advances in electrospun carbon nanofibers and their application in electrochemical energy storage. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 76, 319–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, W.; Ma, D.; Ma, Q.; Bridges, D.; Ma, Y.; Hu, A. Electrospinning of Nanofibers and Their Applications for Energy Devices. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thavasi, V.; Singh, G.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospun nanofibers in energy and environmental applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Greiner, A.; Wendorff, J.H. Functional materials by electrospinning of polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 963–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; Sundaramurthy, J.; Sundarrajan, S.; Babu, V.J.; Singh, G.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Ramakrishna, S. Hierarchical electrospun nanofibers for energy harvesting, production and environmental remediation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3192–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, S.; Subianto, S.; Savych, I.; Jones, D.J.; Rozière, J. Electrospinning: Designed architectures for energy conversion and storage devices. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 4761–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampal, E.S.; Stojanovska, E.; Simon, B.; Kilic, A. A review of nanofibrous structures in lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 300, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguemont, J.; Boulon, L.; Dubé, Y. A comprehensive review of lithium-ion batteries used in hybrid and electric vehicles at cold temperatures. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.S. The Li-ion Rechargeable Battery: A Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiao, X. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of nanostructured LiCoO2 fibers as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 17901–17906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, D.; Jiao, X.; Liu, F. LiCoO2-MgO coaxial fibers: Co-electrospun fabrication, characterization and electrochemical properties. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaju, K.M.; Bruce, P.G. Macroporous LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2: A High-Power and High-Energy Cathode for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2330–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Chao, D.; Baikie, T.; Bai, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Sum, T.C.; Lin, J.; Shen, Z. Hierarchical Porous LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 Nano-/Micro Spherical Cathode Material: Minimized Cation Mixing and Improved Li+ Mobility for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Liu, L.; Jia, Z.; Dai, C.; Xiong, Y. Synergy of Nyquist and Bode electrochemical impedance spectroscopy studies to particle size effect on the electrochemical properties of LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 186, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.S.; Son, J.T. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 cathode materials by electrospinning process. J. Electroceram. 2012, 29, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Ren, X. Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2-Encapsulated Carbon Nanofiber Network Cathodes with Improved Stability and Rate Capability for Li-ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

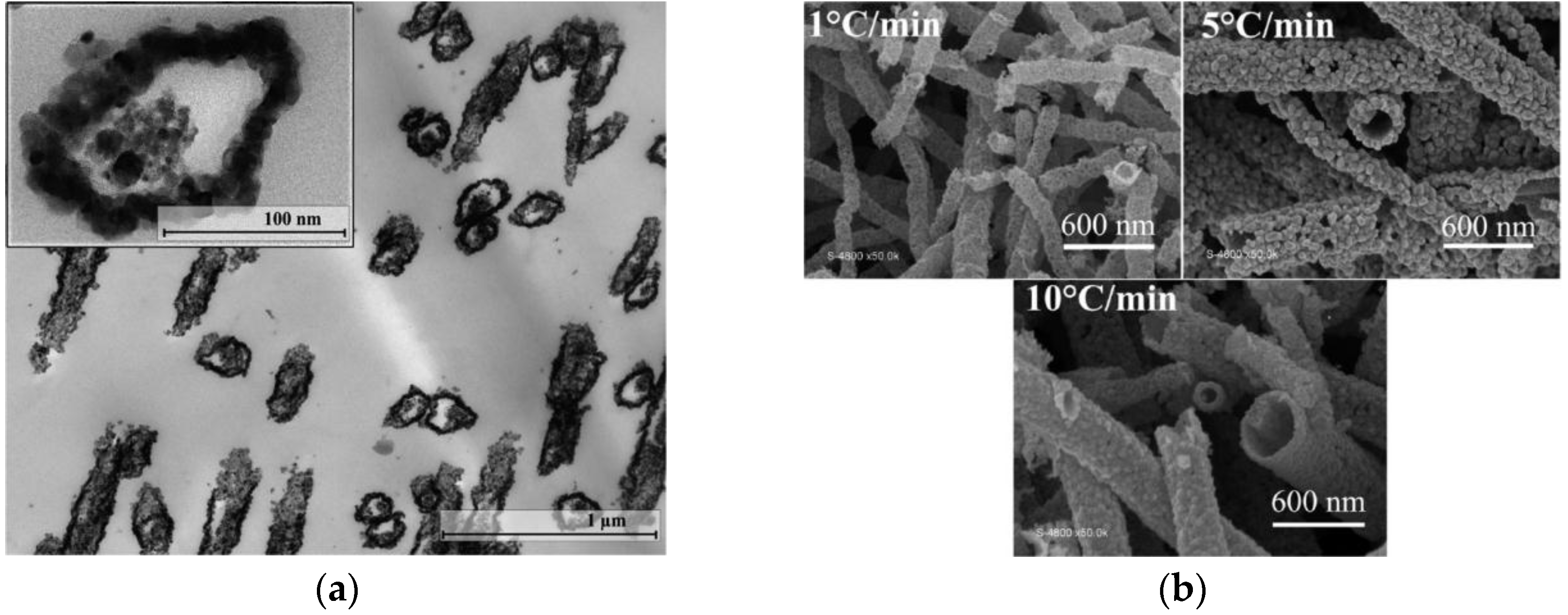

- Min, J.W.; Kalathil, A.K.; Yim, C.J.; Im, W.B. Morphological effects on the electrochemical performance of lithium-rich layered oxide cathodes, prepared by electrospinning technique, for lithium-ion battery applications. Mater. Charact. 2014, 92, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, A.K.; Nanjundaswamy, K.; Goodenough, J. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, L.; Sun, K.; Yu, S.; Wang, R.; Xie, H. Synthesis of nano-LiFePO4 particles with excellent electrochemical performance by electrospinning-assisted method. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 3581–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprakci, O.; Ji, L.; Lin, Z.; Toprakci, H.A.K.; Zhang, X. Fabrication and electrochemical characteristics of electrospun LiFePO4/carbon composite fibers for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 7692–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprakci, O.; Toprakci, H.A.; Ji, L.; Xu, G.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X. Carbon nanotube-loaded electrospun LiFePO4/carbon composite nanofibers as stable and binder-free cathodes for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosono, E.; Wang, Y.; Kida, N.; Enomoto, M.; Kojima, N.; Okubo, M.; Matsuda, H.; Saito, Y.; Kudo, T.; Honma, I.; et al. Synthesis of triaxial LiFePO4 nanowire with a VGCF core column and a carbon shell through the electrospinning method. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.; Christian, P.; DiSalvo, F.; Waszczak, J. Lithium incorporation by vanadium pentoxide. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 2800–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Hu, Y.; Nie, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, T.; Pan, A.; Cao, G. Template-free synthesis of ultra-large V2O5 nanosheets with exceptional small thickness for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2015, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, C.; Chernova, N.A.; Whittingham, M.S. Electrospun nano-vanadium pentoxide cathode. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Li, X.; Bai, Z.; Li, M.; Dong, L.; Xiong, D.; Li, D. Superior lithium storage performance of hierarchical porous vanadium pentoxide nanofibers for lithium ion battery cathodes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 634, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; Xu, L.; Han, C.; Xu, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y. Electrospun ultralong hierarchical vanadium oxide nanowires with high performance for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4750–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Guo, M.; Ding, L.X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Electrospun porous vanadium pentoxide nanotubes as a high-performance cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 173, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ding, X.; Liu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Yin, Z.; Wang, X. Preparation and Characterization of Ultralong Spinel Lithium Manganese Oxide Nanofiber Cathode via Electrospinning Method. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 152, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, G. Preparation and characterization of Li3V2(PO4)3 grown on carbon nanofiber as cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yan, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Chao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yang, G. Bicontinuous Structure of Li3V2(PO4)3 Clustered via Carbon Nanofiber as High-Performance Cathode Material of Li-ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 13934–13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arun, N.; Aravindan, V.; Jayaraman, S.; Madhavi, S. Unveiling the Fabrication of “Rocking-Chair” Type 3.2 and 1.2 V Class Cells Using Spinel LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 as Cathode with Li4Ti5O12. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 24332–24336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, N.; Aravindan, V.; Ling, W.C.; Madhavi, S. Importance of nanostructure for reversible Li-insertion into octahedral sites of LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 and its application towards aqueous Li-ion chemistry. J. Power Sources 2015, 280, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, X.; Chamoun, R.; Shui, J.; Li, J.C.M.; Lu, J.; Amine, K.; Belharouak, I. Enhanced rate performance of LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 fibers synthesized by electrospinning. Nano Energy 2015, 15, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Yang, K.S.; Kojima, M.; Yoshida, K.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.A.; Endo, M. Fabrication of Electrospinning-Derived Carbon Nanofiber Webs for the Anode Material of Lithium-ion Secondary Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2006, 16, 2393–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Chong, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Yu, X. Electrospun pitch/polyacrylonitrile composite carbon nanofibers as high performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2015, 159, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, M.; Wang, M.; Zeng, L.; Yu, Y. Electrospinning with partially carbonization in air: Highly porous carbon nanofibers optimized for high-performance flexible lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2015, 13, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Yang, H.S.; Jung, H.; Mah, S.K.; Kwon, S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Yu, W.R.; Doo, S.G. Facile method to improve initial reversible capacity of hollow carbon nanofiber anodes. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 70, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.S. Enhanced Electrochemical Performance of Electrospun Ag/Hollow Glassy Carbon Nanofibers as Free-standing Li-ion Battery Anode. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 176, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhou, D.; Song, W.L.; Li, X.; Fan, L.Z. Highly stable GeOx@C core-shell fibrous anodes for improved capacity in lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19907–19912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, M.E.; Pham-Cong, D.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.P.; Kim, J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Cho, C.R. Enhanced electrochemical performance of template-free carbon-coated iron (II, III) oxide hollow nanofibers as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 284, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.H.; Ahn, H.J. Carbon nanofiber/cobalt oxide nanopyramid core-shell nanowires for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 272, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, W.J. Hierarchically mesoporous carbon nanofiber/Mn3O4 coaxial nanocables as anodes in lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 281, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Mao, M.; Chou, S.; Liu, H.; Dou, S.; Ng, D.H.L.; Ma, J. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers with effectively encapsulated GeO2 nanocrystals for highly reversible lithium storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 21699–21705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, P.; Reddy, M.V.; Chowdari, B.V.; Ramakrishna, S. Maghemite nanoparticles on electrospun CNFs template as prospective lithium-ion battery anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashuri, M.; He, Q.; Shaw, L.L. Silicon as a potential anode material for Li-ion batteries: Where size, geometry and structure matter. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 74–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Qin, X.; Miao, C.; He, Y.B.; Liang, G.; Zhou, D.; Liu, M.; Han, C.; Li, B.; Kang, F. A honeycomb-cobweb inspired hierarchical core-shell structure design for electrospun silicon/carbon fibers as lithium-ion battery anodes. Carbon 2016, 98, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.S.; Song, W.L.; Wang, J.; Fan, L.Z. Highly uniform silicon nanoparticle/porous carbon nanofiber hybrids towards free-standing high-performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Carbon 2015, 82, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, S. Foamed mesoporous carbon/silicon composite nanofiber anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 281, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shao, J.; Shen, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, X.; He, X.; Song, Y.; Xing, X. Pyrolytic carbon-coated silicon/carbon nanofiber composite anodes for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 298, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, X.; Wu, J.; He, Y.-B.; Du, H.; Li, B.; Kang, F. Electrospun core-shell silicon/carbon fibers with an internal honeycomb-like conductive carbon framework as an anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7112–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Han, F.; Luo, C.; Wang, C. 3D Si/C Fiber Paper Electrodes Fabricated Using a Combined Electrospray/Electrospinning Technique for Li-ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousse, T.; Crosnier, O.; Devaux, X.; Fragnaud, P.; Paillard, P.; Santos-Peña, J.; Schleich, D. Advanced oxide and metal powders for negative electrodes in lithium-ion batteries. Powder Technol. 2002, 128, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Yan, W.; Lv, J.; Guo, Z.; Yu, X.; Chen, Z.; Guo, T.; Zeng, R. Novel three-dimensional tin/carbon hybrid core/shell architecture with large amount of solid cross-linked micro/nanochannels for lithium ion battery application. Energy 2015, 82, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, W.L.; Wang, Z.; Fan, L.Z.; Zhang, Y. Facile Fabrication of Binder-free Metallic Tin Nanoparticle/Carbon Nanofiber Hybrid Electrodes for Lithium-ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 153, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Chen, R. Tin nanoparticle-loaded porous carbon nanofiber composite anodes for high current lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 278, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

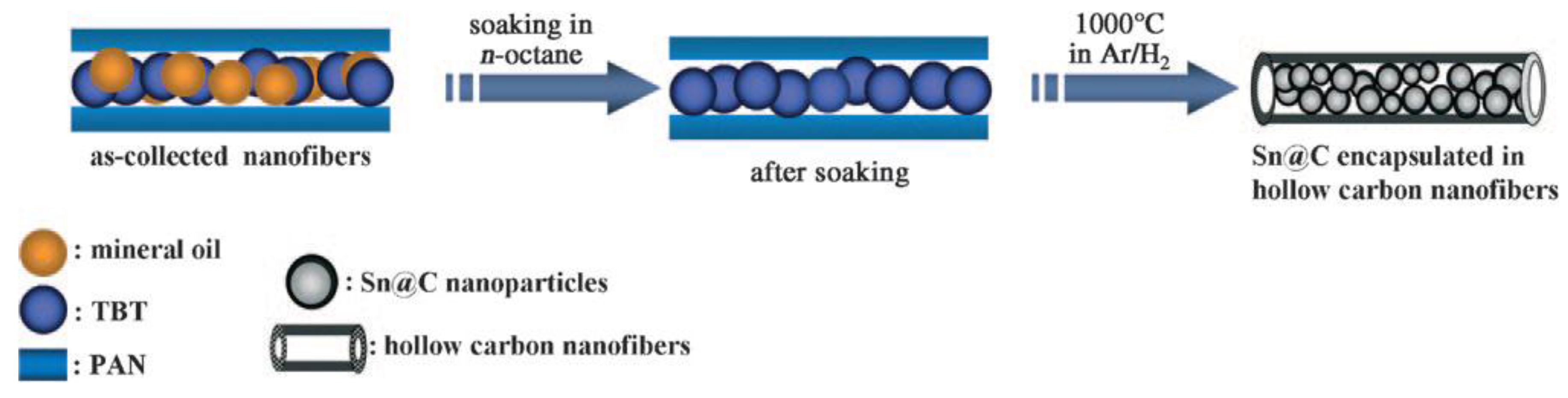

- Yu, Y.; Gu, L.; Wang, C.; Dhanabalan, A.; van Aken, P.A.; Maier, J. Encapsulation of Sn@carbon nanoparticles in bamboo-like hollow carbon nanofibers as an anode material in lithium-based batteries. Angew. Chem. 2009, 48, 6485–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.V.; Subba Rao, G.V.; Chowdari, B.V. Metal oxides and oxysalts as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5364–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macak, J.M.; Tsuchiya, H.; Schmuki, P. High-aspect-ratio TiO2 nanotubes by anodization of titanium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2100–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, R.; Liu, L.; Bohling, C.; Sigmund, W. Conductivity dependence of lithium diffusivity and electrochemical performance for electrospun TiO2 fibers. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

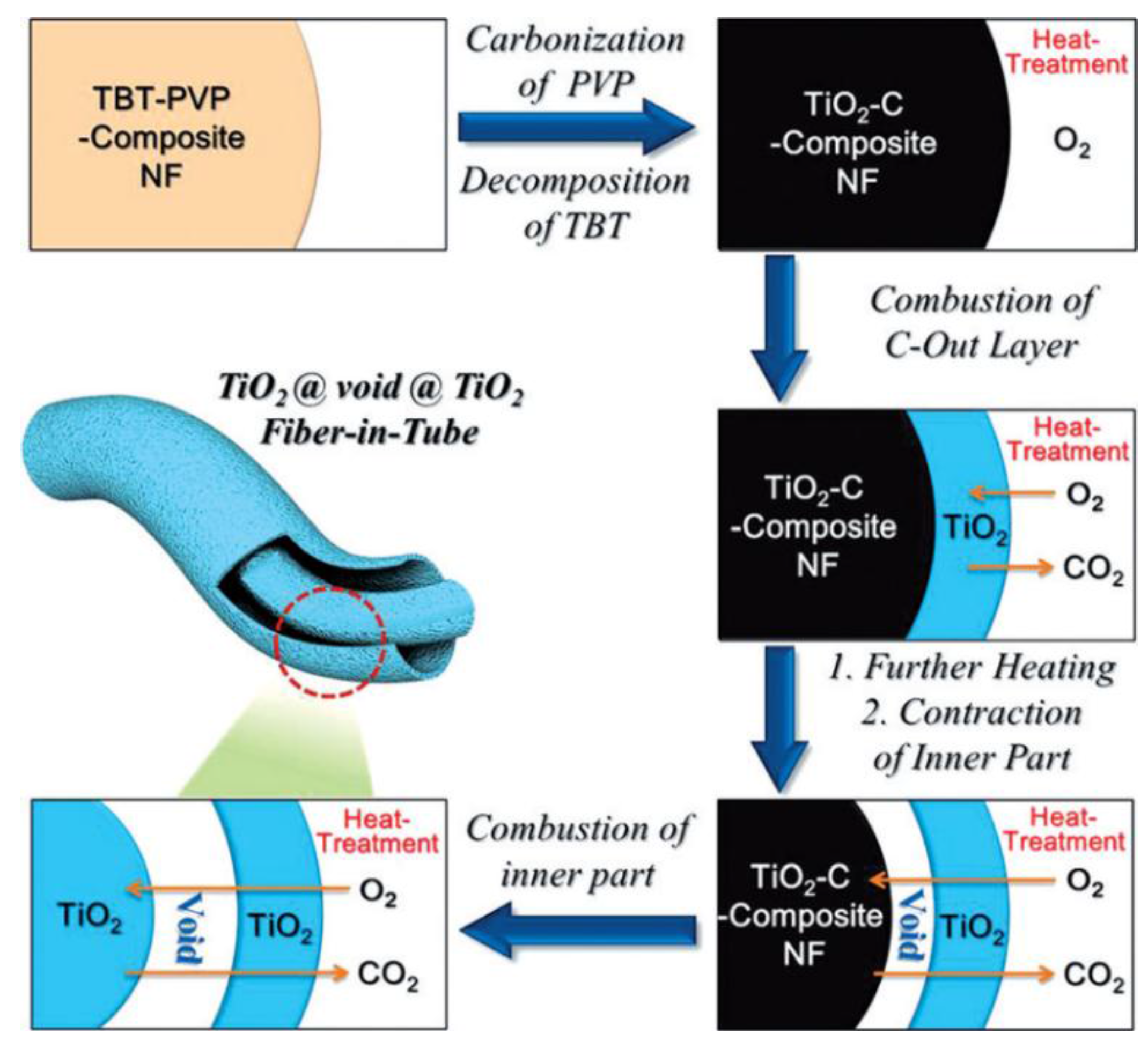

- Cho, J.S.; Hong, Y.J.; Kang, Y.C. Electrochemical properties of fiber-in-tube- and filled-structured TiO2 nanofiber anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Chemistry 2015, 21, 11082–11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ma, D.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. General and controllable synthesis strategy of metal oxide/TiO2 hierarchical heterostructures with improved lithium-ion battery performance. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Yuan, S.; Ma, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Fe3O4-nanoparticle-decorated TiO2 nanofiber hierarchical heterostructures with improved lithium-ion battery performance over wide temperature range. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.V.; Jose, R.; Teng, T.H.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Preparation and electrochemical studies of electrospun TiO2 nanofibers and molten salt method nanoparticles. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 3109–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wu, Y.; Reddy, M.V.; Sreekumaran Nair, A.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Long term cycling studies of electrospun TiO2 nanostructures and their composites with MWCNTs for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Le Viet, A.; Reddy, M.; Jose, R.; Chowdari, B. Nanostructured Nb2O5 polymorphs by electrospinning for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010, 114, 664–671. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, M.V.; Jose, R.; Le Viet, A.; Ozoemena, K.I.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Studies on the lithium ion diffusion coefficients of electrospun Nb2O5 nanostructures using galvanostatic intermittent titration and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 128, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Viet, A.; Reddy, M.V.; Jose, R.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrochemical properties of bare and Ta-substituted Nb2O5 nanostructures. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yin, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J. Bacterial cellulose nanofibrous membrane as thermal stable separator for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 279, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Choi, S.W.; Jo, S.M.; Chin, B.D.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, K.Y. Electrochemical properties and cycle performance of electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride)-based fibrous membrane electrolytes for Li-ion polymer battery. J. Power Sources 2006, 163, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Hu, X.; Dai, C.; Yi, T. Crystal structures of electrospun PVdF membranes and its separator application for rechargeable lithium metal cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 131, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Kim, J.R.; Ahn, Y.R.; Jo, S.M.; Cairns, E.J. Characterization of electrospun PVdF fiber-based polymer electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheruvally, G.; Kim, J.K.; Choi, J.W.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, K.W.; Ahn, H.J. Polymer electrolytes based on an electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) membrane for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 167, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Xu, Y.; Peng, B.; Su, Y.; Jiang, F.; Hsieh, Y.L.; Wei, Q. Coaxial Electrospun Cellulose-Core Fluoropolymer-Shell Fibrous Membrane from Recycled Cigarette Filter as Separator for High Performance Lithium-ion Battery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Cheruvally, G.; Li, X.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, K.W.; Ahn, H.J. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of electrospun, microporous membrane-based composite polymer electrolytes for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2008, 178, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.; Choi, J.W.; Ahn, J.H.; Cheruvally, G.; Chauhan, G.S.; Ahn, H.J.; Nah, C. Novel electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)-in situ SiO2 composite membrane-based polymer electrolyte for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, P.; Long, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, F.; Di, W. The ionic conductivity and mechanical property of electrospun P(VdF-HFP)/PMMA membranes for lithium ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 329, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.; Zhao, X.; Shin, C.; Baek, D.H.; Choi, J.W.; Manuel, J.; Heo, M.Y.; Ahn, J.H.; Nah, C. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of polymer electrolytes based on electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)/polyacrylonitrile blend/composite membranes for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 6088–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xing, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.; Tang, B. Study the effect of ion-complex on the properties of composite gel polymer electrolyte based on Electrospun PVdF nanofibrous membrane. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 151, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, P.; Manuel, J.; Zhao, X.; Kim, D.S.; Ahn, J.H.; Nah, C. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of gel polymer electrolyte based on electrospun polyacrylonitrile nonwoven membranes for lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 6742–6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carol, P.; Ramakrishnan, P.; John, B.; Cheruvally, G. Preparation and characterization of electrospun poly(acrylonitrile) fibrous membrane based gel polymer electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 10156–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Sui, G.; Yang, X. Studies on polymer nanofibre membranes with optimized core-shell structure as outstanding performance skeleton materials in gel polymer electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2014, 267, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanilmaz, M.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. SiO2/polyacrylonitrile membranes via centrifugal spinning as a separator for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 273, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.R.; Ju, D.H.; Lee, W.J.; Zhang, X.; Kotek, R. Electrospun hydrophilic fumed silica/polyacrylonitrile nanofiber-based composite electrolyte membranes. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 3630–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, W.L.; Fan, L.Z.; Song, Y. Facile fabrication of polyacrylonitrile/alumina composite membranes based on triethylene glycol diacetate-2-propenoic acid butyl ester gel polymer electrolytes for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 486, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, W.L.; Fan, L.Z.; Shi, Q. Effect of polyacrylonitrile on triethylene glycol diacetate-2-propenoic acid butyl ester gel polymer electrolytes with interpenetrating crosslinked network for flexible lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 295, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sui, G.; Bi, H.; Yang, X. Radiation-crosslinked nanofiber membranes with well-designed core-shell structure for high performance of gel polymer electrolytes. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 492, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Manuel, J.; Choi, H.; Park, W.H.; Ahn, J.H. Partially oxidized polyacrylonitrile nanofibrous membrane as a thermally stable separator for lithium ion batteries. Polymer 2015, 68, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ji, L.; Guo, B.; Lin, Z.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Alcoutlabi, M.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, X. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of ionic-conducting lithium lanthanum titanate oxide/polyacrylonitrile submicron composite fiber-based lithium-ion battery separators. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Lee, J.H.; Bhat, V.; Lee, S.H. Electrospun polyacrylonitrile microfiber separators for ionic liquid electrolytes in Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 292, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A.; Fu, Y.; Chung, S.H.; Zu, C.; Su, Y.S. Rechargeable Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11751–11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Shi, L.; Mu, D.; Xu, H.; Wu, B. A hierarchical carbon fiber/sulfur composite as cathode material for Li-S batteries. Carbon 2015, 86, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yu, Z.; Gordin, M.L.; Wang, D. Advanced Sulfur Cathode Enabled by Highly Crumpled Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Sheets for High-Energy-Density Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Li, B.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.F.; Shi, J.L.; Wei, F. CaO-Templated Growth of Hierarchical Porous Graphene for High-Power Lithium-Sulfur Battery Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Rao, M.; Aloni, S.; Wang, L.; Cairns, E.J.; Zhang, Y. Porous carbon nanofiber-sulfur composite electrodes for lithium/sulfur cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 5053–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.K.; Guo, Z. Large-scale synthesis of ordered mesoporous carbon fiber and its application as cathode material for lithium-sulfur batteries. Carbon 2015, 81, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Thomas, M.L.; Byon, H.R. In situ synthesis of bipyramidal sulfur with 3D carbon nanotube framework for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 2248–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Cheng, J.; Qu, G.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Ni, W.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. Porous carbon nanofibers formed in situ by electrospinning with a volatile solvent additive into an ice water bath for lithium-ulfur batteries. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 23749–23757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, L.; Park, J.B.; Sun, Y.K.; Wu, F.; Amine, K. Aprotic and aqueous Li-O2 batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5611–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, W.J.; Lau, K.C.; Shin, C.D.; Amine, K.; Curtiss, L.A.; Sun, Y.K. A Mo2C/Carbon Nanotube Composite Cathode for Lithium-Oxygen Batteries with High Energy Efficiency and Long Cycle Life. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 4129–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.J.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, J.K.; Kim, H.T. Sustainable Redox Mediation for Lithium-Oxygen Batteries by a Composite Protective Layer on the Lithium-Metal Anode. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luntz, A.C.; McCloskey, B.D. Nonaqueous Li-air batteries: A status report. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11721–11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Q.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Rooney, D.; Sun, W.; Sun, K. One-dimensional porous La0.5Sr0.5CoO2.91 nanotubes as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for rechargeable lithium-oxygen batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 165, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, W.H.; Yoon, T.H.; Song, S.H.; Jeon, S.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, I.D. Bifunctional composite catalysts using Co3O4 nanofibers immobilized on nonoxidized graphene nanoflakes for high-capacity and long-cycle Li-O2 batteries. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4190–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Xia, L.; Wang, S.; Ding, L.X.; Li, D.; Xiao, K.; Dai, S.; Wang, H. Hierarchical Mesoporous/Macroporous Perovskite La0.5Sr0.5CoO3 − x Nanotubes: A Bifunctional Catalyst with Enhanced Activity and Cycle Stability for Rechargeable Lithium Oxygen Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 22478–22486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.J.; Kim, I.T.; Kim, Y.B.; Shin, M.W. Self-standing, binder-free electrospun Co3O4/carbon nanofiber composites for non-aqueous Li-air batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 182, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

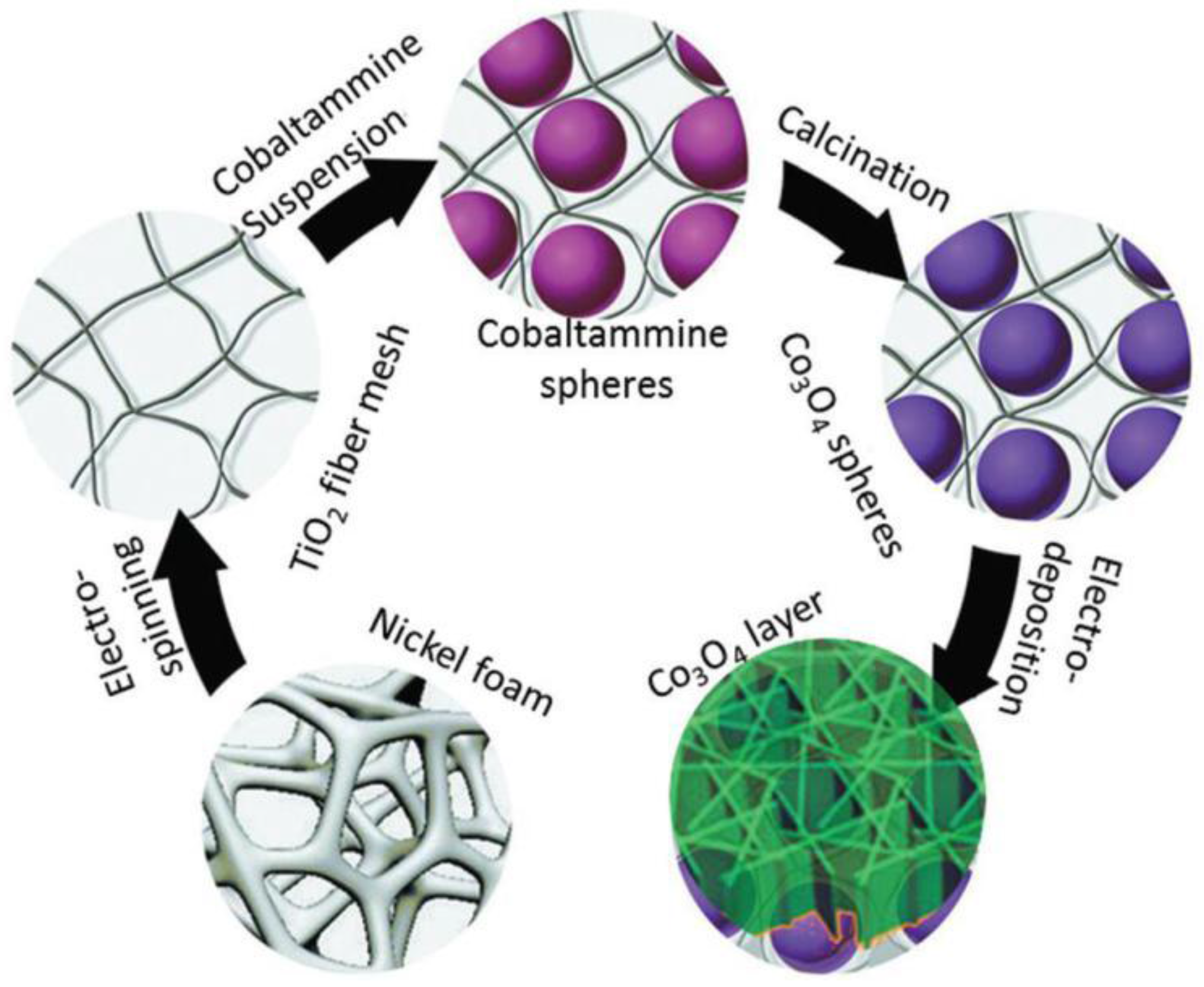

- Xu, S.M.; Zhu, Q.C.; Du, F.H.; Li, X.H.; Wei, X.; Wang, K.X.; Chen, J.S. Co3O4-based binder-free cathodes for lithium-oxygen batteries with improved cycling stability. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 8678–8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Seo, M.H.; Choi, S.M.; Cho, J.; Huber, G.W.; Kim, W.B. Highly improved oxygen reduction performance over Pt/C-dispersed nanowire network catalysts. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Joh, H.I.; Jo, S.M.; Ahn, D.J.; Ha, H.Y.; Hong, S.A.; Kim, S.K. Preparation and characterization of Pt nanowire by electrospinning method for methanol oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 4827–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, K.; Du, F.; Xia, Z.; Durstock, M.; Dai, L. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 2009, 323, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolini, E.; Salgado, J.R.; Gonzalez, E.R. The stability of Pt-M (M = first row transition metal) alloy catalysts and its effect on the activity in low temperature fuel cells: A literature review and tests on a Pt-Co catalyst. J. Power Sources 2006, 160, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.; Hsu, C.S.; Huang, J.B.; Hsu, P.H.; Hwang, B.H. Preparation and characterization of SOFC cathodes made of SSC nanofibers. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 620, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabae, Y.; Pointon, K.D.; Irvine, J.T.S. Electrochemical oxidation of solid carbon in hybrid DCFC with solid oxide and molten carbonate binary electrolyte. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Seo, M.H.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, W.B. Pt and PtRh nanowire electrocatalysts for cyclohexane-fueled polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Han, G.; Yang, B. Fabrication of the catalytic electrodes for methanol oxidation on electrospinning-derived carbon fibrous mats. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Nam, S.H.; Shim, H.S.; Ahn, H.J.; Anand, M.; Kim, W.B. Electrospun bimetallic nanowires of PtRh and PtRu with compositional variation for methanol electrooxidation. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, J.L.; Chen, C.; Li, J.C.M. Evolution of Nanoporous Pt-Fe Alloy Nanowires by Dealloying and their Catalytic Property for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 3357–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.C.; Wang, R.; Hoque, M.A.; Zamani, P.; Abureden, S.; Chen, Z. Morphology and composition controlled platinum-cobalt alloy nanowires prepared by electrospinning as oxygen reduction catalyst. Nano Energy 2014, 10, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouri, Z.K.; Barakat, N.A.; Kim, H.Y. Influence of copper content on the electrocatalytic activity toward methanol oxidation of CoxCuy alloy nanoparticles-decorated CNFs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Dai, C.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Z.; Ren, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, J. The effect of different nitrogen sources on the electrocatalytic properties of nitrogen-doped electrospun carbon nanofibers for the oxygen reduction reaction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 4673–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Z.; You, T. Free-standing nitrogen-doped carbon nanofiber films as highly efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9528–9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Yu, J.; Shi, T.; Zhou, X.; Bai, X.; Huang, J.Y. Nitrogen-doped ultrathin carbon nanofibers derived from electrospinning: Large-scale production, unique structure, and application as electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 9862–9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Kolla, P.; Zhao, Y.; Fong, H.; Smirnova, A.L. Lignin-derived electrospun carbon nanofiber mats with supercritically deposited Ag nanoparticles for oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 130, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamer, B.M.; El-Newehy, M.H.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Kim, H.Y.; Barakat, N.A.M. Cobalt-incorporated, nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers as effective non-precious catalyst for methanol electrooxidation in alkaline medium. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 498, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Yuan, P.; She, X.; Xia, Y.; Komarneni, S.; Xi, K.; Che, Y.; Yao, X.; Yang, D. Sustainable seaweed-based one-dimensional (1D) nanofibers as high-performance electrocatalysts for fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 14188–14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, J.P.; Jiang, R.; Chu, D.; Fedkiw, P.S. Oxygen electroreduction on Fe or Co-containing carbon fibers. Carbon 2014, 79, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, S.; Jeong, B.; Lee, J. A facile route for preparation of non-noble CNF cathode catalysts in alkaline ethanol fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 9186–9190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.; Brooks, R.M.; El-Halwany, M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Khamaj, J.A.; EL-Newehy, M.H.; Barakat, N.A.; Kim, H.Y. Fabrication of Electrical Conductive NiCu-Carbon Nanocomposite for Direct Ethanol Fuel Cells. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 7025–7032. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, J. Onion-like graphitic nanoshell structured Fe-N/C nanofibers derived from electrospinning for oxygen reduction reaction in acid media. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 30, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Luo, J.; Zhu, J. Optimized electrospinning synthesis of iron-nitrogen-carbon nanofibers for high electrocatalysis of oxygen reduction in alkaline medium. Nanotechnology 2015, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, N.A.M.; Motlak, M.; Kim, B.S.; El-Deen, A.G.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Hamza, A.M. Carbon nanofibers doped by NixCo1 − x alloy nanoparticles as effective and stable non precious electrocatalyst for methanol oxidation in alkaline media. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2014, 394, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, G.M.K.; Barakat, N.A.M.; Bastaweesy, A.M.; Ashour, E.A.; Abdelmoez, W.; El-Newehy, M.H.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Kim, H.Y. Hierarchical TiO2/ZnO Nanostructure as Novel Non-precious Electrocatalyst for Ethanol Electrooxidation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryamas, A.B.; Anilkumar, G.M.; Sago, S.; Ogi, T.; Okuyama, K. Electrospun Pt/SnO2 nanofibers as an excellent electrocatalysts for hydrogen oxidation reaction with ORR-blocking characteristic. Catal. Commun. 2013, 33, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, S.; Subianto, S.; Savych, I.; Tillard, M.; Jones, D.J.; Rozière, J. Dopant-Driven Nanostructured Loose-Tube SnO2 Architectures: Alternative Electrocatalyst Supports for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 18298–18307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savych, I.; Subianto, S.; Nabil, Y.; Cavaliere, S.; Jones, D.; Roziere, J. Negligible degradation upon in situ voltage cycling of a PEMFC using an electrospun niobium-doped tin oxide supported Pt cathode. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 16970–16976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Lou, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Preparation and characterization of Pt/TiO2 nanofibers catalysts for methanol electro-oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 178, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savych, I.; Bernard d’Arbigny, J.; Subianto, S.; Cavaliere, S.; Jones, D.J.; Rozière, J. On the effect of non-carbon nanostructured supports on the stability of Pt nanoparticles during voltage cycling: A study of TiO2 nanofibres. J. Power Sources 2014, 257, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Wycisk, R.; Pintauro, P.; Yarlagadda, V.; Van Nguyen, T. Electrospun Nafion®/Polyphenylsulfone Composite Membranes for Regenerative Hydrogen Bromine Fuel Cells. Materials 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-E.; Juon, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Shul, Y.-G.; Cho, K.Y. Silicon carbide fiber-reinforced composite membrane for high-temperature and low-humidity polymer exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 16474–16485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Higgins, D.C.; Lee, D.U.; Prabhudev, S.; Hassan, F.M.; Chabot, V.; Lui, G.; Jiang, G.; Choi, J.Y.; Rasenthiram, L.; et al. Biomimetic design of monolithic fuel cell electrodes with hierarchical structures. Nano Energy 2016, 20, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Xiao, M.; Han, D.; Meng, Y. A proton exchange membrane fabricated from a chemically heterogeneous nonwoven with sandwich structure by the program-controlled co-electrospinning process. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3415–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, B.; Gwee, L.; Salas-dela Cruz, D.; Winey, K.I.; Elabd, Y.A. Super proton conductive high-purity nafion nanofibers. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollá, S.; Compañ, V.; Gimenez, E.; Blazquez, A.; Urdanpilleta, I. Novel ultrathin composite membranes of Nafion/PVA for PEMFCs. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 9886–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballengee, J.B.; Pintauro, P.N. Morphological Control of Electrospun Nafion Nanofiber Mats. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, B568–B572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hao, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhong, S.; Na, H.; Wang, D. Fabrication of sulfonated poly(ether ether ketone ketone) membranes with high proton conductivity. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 281, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Wycisk, R.; Pintauro, P.N. Nafion/PVdF nanofiber composite membranes for regenerative hydrogen/bromine fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 490, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneeratana, V.; Bass, J.D.; Azaïs, T.; Patissier, A.; Vallé, K.; Maréchal, M.; Gebel, G.; Laberty-Robert, C.; Sanchez, C. Fractal inorganic-organic interfaces in hybrid membranes for efficient proton transport. Adv. Functi. Mater. 2013, 23, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketpang, K.; Lee, K.; Shanmugam, S. Facile synthesis of porous metal oxide nanotubes and modified nafion composite membranes for polymer electrolyte fuel cells operated under low relative humidity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 16734–16744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Z.; Wang, C.; Hsu, C.C.; Cheng, I.C. Ultrafast synthesis of carbon-nanotube counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells using an atmospheric-pressure plasma jet. Carbon 2016, 98, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokurala, K.; Mallick, S.; Bhargava, P. Alternative quaternary chalcopyrite sulfides (Cu2FeSnS4 and Cu2CoSnS4) as electrocatalyst materials for counter electrodes in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 2016, 305, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugathan, V.; John, E.; Sudhakar, K. Recent improvements in dye sensitized solar cells: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Viet, A.; Jose, R.; Reddy, M.; Chowdari, B.; Ramakrishna, S. Nb2O5 photoelectrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells: Choice of the polymorph. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 21795–21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jose, R.; Fujihara, K.; Wang, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Structural and optical properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofibers. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 6536–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, S.S.; Shim, C.S.; Kim, H.; Patil, J.V.; Ahn, D.H.; Patil, P.S.; Hong, C.K. Evaluation of various diameters of titanium oxide nanofibers for efficient dye sensitized solar cells synthesized by electrospinning technique: A systematic study and their application. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 166, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, R.; Ke, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, B.; Ramakrishna, S. Anatase mesoporous TiO2 nanofibers with high surface area for solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. Small 2010, 6, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Leung, W.W. Application of a bilayer TiO2 nanofiber photoanode for optimization of dye-sensitized solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4559–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.G.; Wan, F.R.; Chen, Q.W.; Li, J.J.; Xu, D.S. Controlling synthesis of well-crystallized mesoporous TiO2 microspheres with ultrahigh surface area for high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 2870–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, C.; Song, H.; Son, S.; Jang, J. Designed architecture of multiscale porous TiO2 nanofibers for dye-sensitized solar cells photoanode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 5287–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieu, N.T.; Baik, S.J.; Chung, O.H.; Park, J.S. Fabrication and characterization of electrospun carbon nanotubes/titanium dioxide nanofibers used in anodes of dye-sensitized solar cells. Synth. Met. 2014, 193, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, D.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, B.; Park, N.G.; Kim, K.; Shin, J.H.; Choi, I.S.; Ko, M.J. Highly durable and flexible dye-sensitized solar cells fabricated on plastic substrates: PVdF-nanofiber-reinforced TiO2 photoelectrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8950–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, G.; Jiao, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, S. Efficiency enhancement of ZnO-based dye-sensitized solar cell by hollow TiO2 nanofibers. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 611, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, A.; Elbohy, H.; Kelkar, A.D.; Qiao, Q.; Zai, J.; Qian, X.; Zhang, L. Electrospun carbon nanofibers with surface-attached platinum nanoparticles as cost-effective and efficient counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Energy 2015, 11, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookhakian, M.; Ridwan, N.; Zalnezhad, E.; Yoon, G.; Azarang, M.; Mahmoudian, M.; Alias, Y. Layer-by-Layer Electrodeposited Reduced Graphene Oxide-Copper Nanopolyhedra Films as Efficient Platinum-Free Counter Electrodes in High Efficiency Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Galipeau, D.; Fong, H.; Qiao, Q. Electrospun carbon nanofibers as low-cost counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 3572–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Jung, H.R.; Lee, W.J. Hollow activated carbon nanofibers prepared by electrospinning as counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 102, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, W.J. Electrospun activated carbon nanofibers with hollow core/highly mesoporous shell structure as counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 239, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.M.A.; Motlak, M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Yasin, A.S.; El-Newehy, M.H.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Barakat, N.A.M. Synthesis, characterization and performance as a Counter Electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells of CoCr-decorated carbon nanofibers. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlak, M.; Barakat, N.A.M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Hamza, A.M.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, C.S.; Khalil, K.A.; Almajid, A.A. High performance of NiCo nanoparticles-doped carbon nanofibers as counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 160, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, N.A.M.; Shaheer Akhtar, M.; Yousef, A.; El-Newehy, M.; Kim, H.Y. Pd-Co-doped carbon nanofibers with photoactivity as effective counter electrodes for DSSCs. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, A.; Akhtar, M.S.; Barakat, N.A.M.; Motlak, M.; Yang, O.B.; Kim, H.Y. Effective NiCu NPs-doped carbon nanofibers as counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 102, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, K.; Subramania, A.; Sivasankar, N. Influence of earth-abundant bimetallic (Fe-Ni) nanoparticle-embedded CNFs as a low-cost counter electrode material for dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 43611–43619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, K.; Subramania, A.; Sivasankar, N.; Mallick, S. Electrospun TiC embedded CNFs as a low cost platinum-free counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cell. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016, 75, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Lee, J.; Vincent Joseph, K.L.; Lee, H.I.; Kim, J.K.; Yoon, S.; Lee, J. Low-cost electrospun WC/C composite nanofiber as a powerful platinum-free counter electrode for dye sensitized solar cell. Nano Energy 2014, 9, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Graetzel, M. Solvent-Free Ionic Liquid Electrolytes for Mesoscopic Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 2187–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Park, K.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Yim, S.H.; Zhao, X.G.; Gu, H.B.; Jin, E.M. Dye-sensitized solar cells based on electrospun poly(vinylidenefluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) nanofibers. Polym. Bull. 2013, 70, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaith, H.J.; Schmidt-Mende, L. Advances in Liquid-Electrolyte and Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3187–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Park, S.H.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, W.K.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, M.R. Effect of electrolyte in electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) nanofibers on dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2009, 93, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, E.; Subramania, A.; Fei, Z.; Dyson, P.J. Effect of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium iodide containing electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) membrane electrolyte on the photovoltaic performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Won, D.H.; Choi, H.J.; Hwang, W.P.; Jang, S.I.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, J.U.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, M.R. Dye-sensitized solar cells based on electrospun polymer blends as electrolytes. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, E.; Subramania, A.; Fei, Z.; Dyson, P.J. High-performance dye-sensitized solar cell based on an electrospun poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)/cobalt sulfide nanocomposite membrane electrolyte. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 52026–52032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.G.; Jin, E.M.; Park, J.Y.; Gu, H.B. Hybrid polymer electrolyte composite with SiO2 nanofiber filler for solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 103, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethupathy, M.; Pandey, P.; Manisankar, P. Evaluation of photovoltaic efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells fabricated with electrospun PVdF-PAN-Fe2O3 composite membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethupathy, M.; Ravichandran, S.; Manisankar, P. Preparation of PVdF-PAN-V2O5 hybrid composite membrane by electrospinning and fabrication of dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2014, 9, 3166–3180. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Yan, J.; Wei, T.; Zhi, L.; Ning, G.; Li, T.; Wei, F. Asymmetric Supercapacitors Based on Graphene/MnO2 and Activated Carbon Nanofiber Electrodes with High Power and Energy Density. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 797–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Wu, X.; Han, Q.; Wang, X. Graphene oxide-MnO2 nanocomposites for supercapacitors. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2822–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y. An overview of the applications of graphene-based materials in supercapacitors. Small 2012, 8, 1805–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Song, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhong, M.; Guo, Q.; Liu, L. Phenolic-based carbon nanofiber webs prepared by electrospinning for supercapacitors. Mater. Lett. 2012, 76, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.W.; Tran, C.; Mallajoysula, A.T.; Doorn, S.K.; Mohite, A.; Gupta, G.; Kalra, V. High-energy density nanofiber-based solid-state supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Yang, K.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Kim, Y.J.; An, B.; Oshida, K. Solvent-induced porosity control of carbon nanofiber webs for supercapacitor. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 10496–10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Kang, F. Preparation of microporous carbon nanofibers from polyimide by using polyvinyl pyrrolidone as template and their capacitive performance. J. Power Sources 2015, 278, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Song, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhai, X.; Zhong, M.; Guo, Q.; Liu, L. Preparation and one-step activation of microporous carbon nanofibers for use as supercapacitor electrodes. Carbon 2013, 51, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Z.; Yan, X.; Lang, J.; Xue, Q. Enhancement of capacitance performance of flexible carbon nanofiber paper by adding graphene nanosheets. J. Power Sources 2012, 199, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Song, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, C.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Xie, E. Facilitated transport channels in carbon nanotube/carbon nanofiber hierarchical composites decorated with manganese dioxide for flexible supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wu, X.F. Graphene-beaded carbon nanofibers for use in supercapacitor electrodes: Synthesis and electrochemical characterization. J. Power Sources 2013, 222, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhao, N.; Song, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Guo, Q.; Liu, L. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped electrospun carbon nanofibers with superior performance as efficient supercapacitor electrodes in alkaline solution. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 185, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Chen, B.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Shao, C.; Liu, Y. Highly dispersed Fe3O4 nanosheets on one-dimensional carbon nanofibers: Synthesis, formation mechanism, and electrochemical performance as supercapacitor electrode materials. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 5034–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouali, S.; Garakani, M.A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z.L.; Heidari, E.K.; Huang, J.Q.; Huang, J.; Kim, J.K. Electrospun Carbon Nanofibers with in Situ Encapsulated Co3O4 Nanoparticles as Electrodes for High-Performance Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 13503–13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghouri, Z.K.; Barakat, N.; Alam, A.M.; Park, M.; Han, T.H.; Kim, H.Y. Facile synthesis of Fe/CeO2-doped CNFs and their capacitance behavior. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2015, 10, 2064–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, M.; Manivannan, A.; Meng, F.; Wu, N. Highly conductive electrospun carbon nanofiber/MnO2 coaxial nano-cables for high energy and power density supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.H.; Kang, F. Coaxial carbon nanofibers/MnO2 nanocomposites as freestanding electrodes for high-performance electrochemical capacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 9240–9247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Du, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Encapsulation of manganese oxides nanocrystals in electrospun carbon nanofibers as free-standing electrode for supercapacitors. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 7402–7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Balakrishna, R.; Reddy, M.V.; Nair, A.S.; Chowdari, B.V.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Functional properties of electrospun NiO/RuO2 composite carbon nanofibers. J. Alloy. Compd. 2012, 517, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.S.; Kim, B.H. Highly conductive, porous RuO2/activated carbon nanofiber composites containing graphene for electrochemical capacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 186, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Kim, B.H. Zinc oxide/activated carbon nanofiber composites for high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Kim, C.H.; Yang, K.S.; Rahy, A.; Yang, D.J. Electrospun vanadium pentoxide/carbon nanofiber composites for supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 83, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, T.S.; Tuller, H.L.; Youn, D.Y.; Kim, H.G.; Kim, I.D. Facile synthesis and electrochemical properties of RuO2 nanofibers with ionically conducting hydrous layer. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 9172–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwan, J.; Sahoo, A.; Yadav, K.L.; Sharma, Y. Porous, One dimensional and High Aspect Ratio Mn3O4 Nanofibers: Fabrication and Optimization for Enhanced Supercapacitive Properties. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 174, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Fan, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Song, D.; Bai, X. Hollow NiO nanofibers modified by citric acid and the performances as supercapacitor electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 92, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binitha, G.; Soumya, M.S.; Madhavan, A.A.; Praveen, P.; Balakrishnan, A.; Subramanian, K.R.V.; Reddy, M.V.; Nair, S.V.; Nair, A.S.; Sivakumar, N. Electrospun α-Fe2O3 nanostructures for supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 11698–11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Mei, L.; Duan, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Lu, B. Simple method for the preparation of highly porous ZnCo2O4 nanotubes with enhanced electrochemical property for supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 123, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. Synthesis, structure and electrochemical properties of lanthanum manganese nanofibers doped with Sr and Cu. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 638, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. Symmetric/Asymmetric Supercapacitor Based on the Perovskite-type Lanthanum Cobaltate Nanofibers with Sr-substitution. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 178, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, B.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X. Sr-doped Lanthanum Nickelate Nanofibers for High Energy Density Supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 174, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Diameter/μm | Structure | DC (after Cycle Number)/mAh·g−1 | Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiCoO2 | 0.5–2 | fiber | 123 (20) | 20 mA/g | [41] |

| LiCoO2–MgO | 1–2 | core-shell fiber | 163 (40) | 20 mA/g | [42] |

| LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2 | 0.3 | particle | 160 (5) | 20 mA/g | [45] |

| LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 | 0.1–0.8 | nanofiber | 116 (30) | 85 mA/g | [46] |

| Li1.2Mn0.54Ni0.13Co0.13O2/CNFs | - | nanofiber | 176.7 (100) | 1 C | [47] |

| Li1.2Ni0.17Co0.17Mn0.5O2 | 0.1–0.5 | nanofiber | 141–205 (20) | 14.2 mA/g | [48] |

| LiFePO4/C | - | fiber | 131–145 (0.1) | - | [51] |

| LiFePO4/CNT/C | 0.168 | nanofiber | 169 (average) | 0.05 C | [52] |

| LiFePO4/CNT/C | - | core-shell fiber | - | - | [53] |

| V2O5 | 0.2–0.5 | nanofiber | 240 (25) | 0.1 mA/cm2 | [56] |

| V2O5 | 0.2–0.4 | hierarchical porous nanofiber | 133.9 (100) | 800 mA/g | [57] |

| V2O5 | 0.1–0.2 | hierarchical nanowire | 201 (30) | 30 mA/g | [58] |

| V2O5 | 0.3–0.5 | porous nanotube | 130.5 (50) | 0.2 C | [59] |

| LiMn2O4 | 0.17 | porous network | 146 (1) | 0.1 C | [60] |

| Li3V2(PO4)3/CNF | 0.3 | nanofiber | 102 (1000) | 20 C | [61] |

| Li3V2(PO4)3/CNF | 0.18–0.43 | nanofiber | 118.9 (1000) | 20 C | [62] |

| LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 | <0.2 | nanofiber | 138 (1) | 50 mA/g | [63] |

| LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 | 0.05–0.25 | nanofiber | 120 (50) | 0.01 mA/cm | [64] |

| LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 | 0.05–0.1 | nanofiber | 300 (1) | 27 mA/g | [65] |

| Material | Diameter/μm | Structure | DC (after Cycle Number)/mAh·g−1 | Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | 0.2–0.3 | nanofiber | 350 | 100 mA/g | [66] |

| Carbon | 0.3–0.4 | nanofiber | 255 (200) | 0.2 A/g | [67] |

| Carbon | 0.1–0.2 | porous nanofiber | 1780 (40) | 50 mA/g | [68] |

| Carbon | 0.9–1.2 | hollow nanofiber | 900.6 (1) | 100 mA/g | [69] |

| Ag/C | ~0.3 | hollow nanofiber | 600.15 (100) | 50 mA/g | [70] |

| GeOx@C | 1 | core-shell | 875 (400) | 160 mA/g | [71] |

| Co3O4/CNF | 0.8–1.2 | core-shell nanowire | 795 (50) | 100 mA/g | [73] |

| Mn3O4/CNF | 0.5–1 | hierarchically mesoporous | 760 (50) | 100 mA/g | [74] |

| N/GeO2-CNFs | 0.075 | nanofiber | 1031 (200) | 100 mA/g | [75] |

| Si/C | 2–5 | hollow fiber | 725 (40) | 0.2 A/g | [78] |

| Si/C | 0.6–0.8 | porous nanofiber | 870 (100) | 0.1 A/g | [79] |

| Si/C | — | hollow fiber | 1045 (20) | 100 mA/g | [80] |

| Si/C | 0.186 | nanofiber | 1215.2 (50) | 600 mA/g | [81] |

| Si/C | ~2 | core-shell | 603 (300) | 0.5 A/g | [82] |

| Si/C | ~0.2 | Fiber paper | 1267 (100) | 500 mA/g | [83] |

| Sn/C | 0.1–0.18 | core-shell | 546.7 (100) | 40 mA/g | [85] |

| Sn/C | ~0.2 | porous nanofiber | 774 (200) | 0.8 A/g | [87] |

| Sn/C | 0.15–0.25 | Hollow nanofiber | 737 (200) | 0.5 C | [88] |

| TiO2 | ~0.119 | nanofiber | 176.7 (100) | 0.1 C | [91] |

| TiO2 | ~0.5 | fiber-in-tube | 177 (1000) | 200 mA/g | [92] |

| Co3O4/TiO2 | ~0.3 | hierarchical | 602.7 (480) | 200 mA/g | [93] |

| Material | Diameter/μm | Conductivity/mS·cm−1 (T/°C) | DC (after-1st)/mAh·g−1 (Rate/C) | Anodic Stability Voltage/V (vs. Li/Li+) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVdF | 1–1.65 | 1.0 (25) | - | 4.5 | [103] |

| PVdF-HFP | 1 | 1.0 (20) | 136–142 (0.1) | 4.5 | [104] |

| PVdF-HFP | 0.512–0.710 | 6.16 (20) | 138–184 (0.2) | 5.0 | [105] |

| PVdF-HFP/SiO2 | 2–5 | 4.3 (25) | 139–170 (0.1) | - | [106] |

| PVdF-HEP/SiO2 | 1–2 | 8.06 (20) | 153–170 (0.1) | >4.5 | [107] |

| PVdF-HEP/PMMA | 0.200–0.350 | 2.0 (25) | 133.5–145 (0.1) | - | [108] |

| PVdF-HEP/PAN | 0.320–0.490 | 1.0 (25) | 131–145 (0.1) | >4.6 | [109] |

| PVdF/SiO2-PAALi | 0.750 | 3.5 (25) | 151–156.5 (0.1) | 5.05 | [110] |

| PAN | 0.350 | 2.14 (25) | 135–150 (0.1) | >4.7 | [111] |

| PAN | 0.880–1.260 | 1.7 (20) | 108–113 (0.5) | - | [112] |

| PAN-PMMA | 0.2–1.0 | 5.1 (-) | 127–135 (0.1) | 5.2 | [113] |

| PAN/SiO2 | 0.8–1.4 | 2.8–3.6 (-) | −163(0.2) | 4.75 | [114] |

| PAN/SiO2 | 0.100–0.300 | 11 (-) | 127–139 (0.5) | 5.0 | [115] |

| PAN/Al2O3-TEGDA-BA | 3–5 | 2.35 (25) | 240.4 (0.1) | >4.5 | [116] |

| PAN-TEGDA-BA | 0.182 | 5.9 (25) | 127–163.6 (0.1) | >5.0 | [117] |

| PAN-PEO | 0.250–0.330 | 5.36 (-) | 134 (0.1) | - | [118] |

| PAN-LLTO | 0.250 | 1.95 (25) | 148–162 (0.2) | 5.0 | [121] |

| Material | Diameter/nm | Voc/V | Jsc/mA·cm−2 | FF (%) | η (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNF+Pt NPs | 250 | 0.83 | 12.66–13.33 | 65.6–68.8 | 7–8 | [193] |

| CNF | 250 | 0.76 | 12.6 | 57 | 5.5 | [195] |

| H-ACNF | 190/270 | 0.73 | 14.5 | 62 | 6.58 | [196] |

| Meso-HACNF | 200/360 | 0.73/0.74 | 15.4/15.3 | 64/61 | 7.21/6.91 | [197] |

| CNF+Co Cr NPs | - | 0.685 | 8.784 | 54 | 3.27 | [198] |

| CNF+Co Ni NPs | - | 0.74 | 11.12 | 54 | 4.47 | [199] |

| CNF+Co Pd NPs | 150 | 9.8 | 0.705 | 36 | 2.5 | [200] |

| CNF+Cu Ni NPs | - | 0.70 | 7.67 | 65 | 3.5 | [201] |

| CNF+Fe Ni NPs | 230 | 0.72 | 10.1 | 65 | 4.7 | [202] |

| CNF/TiC | 280–300 | 0.73/0.72/0.72 | 9.29/9.71/9.56 | 62/64/63 | 4.2/4.5/4.3 | [204] |

| Material | Voc/V | Jsc/mA·cm−2 | FF (%) | η (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVdF-HFP | 0.75 | 12.3 | 57 | 5.21 | [208] |

| PVdF-HFP | 0.78/0.76/0.77 | 5.759/6.028/5.378 | 66.18/68.05/66.27 | 2.98//3.13/2.75 | [206] |

| BMImI-esPME | 0.71 | 13.10 | 69 | 6.42 | [209] |

| PVdF-HFP/PS | 0.76 | 11.8 | 66 | 5.75 | [210] |

| PVdF-HFP/CoS | 0.73 | 14.42 | 70 | 7.34 | [211] |

| PEO-PVdF-HFP-SiO2 | 0.58/0.60/0.59 | 13.37/13.63/13.18 | 60.24/59.54/59.67 | 4.68/4.85/4.66 | [212] |

| PVdF-PAN-Fe2O3 | 0.77 | 10.4 | 62 | 4.9 | [213] |

| PVdF-PAN-V2O5 | 0.78 | 13.8 | 72 | 7.75 | [214] |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, G.; Sun, L.; Xie, H.; Liu, J. Electrospinning of Nanofibers for Energy Applications. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano6070129

Sun G, Sun L, Xie H, Liu J. Electrospinning of Nanofibers for Energy Applications. Nanomaterials. 2016; 6(7):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano6070129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Guiru, Liqun Sun, Haiming Xie, and Jia Liu. 2016. "Electrospinning of Nanofibers for Energy Applications" Nanomaterials 6, no. 7: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano6070129