Calcium Orthophosphate-Containing Biocomposites and Hybrid Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Inorganic Phases | wt % | Bioorganic Phases | wt % |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaPO4 (biological apatite) | ~60 | collagen type I | ~20 |

| water | ~9 | non-collagenous proteins: osteocalcin, osteonectin, osteopontin, thrombospondin, morphogenetic proteins, sialoprotein, serum proteins | ~3 |

| carbonates | ~4 | other traces: polysaccharides, lipids, cytokines | balance |

| citrates | ~0.9 | primary bone cells: osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteoclasts | balance |

| sodium | ~0.7 | ||

| magnesium | ~0.5 | ||

| other traces: Cl−, F−, K+ Sr2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Fe2+ | balance |

2. General Information and Knowledge

| Inorganic | Bioorganic |

|---|---|

| hardness, brittleness | elasticity, plasticity |

| high density | low density |

| thermal stability | permeability |

| hydrophilicity | hydrophobicity |

| high refractive index | selective complexation |

| mixed valence slate (red-ox) | chemical reactivity |

| strength | bioactivity |

3. The Major Constituents

3.1. CaPO4

| Ca/P Molar Ratio | Compound | Formula | Solubility at 25 °C, −log (Ks) | Solubility at 25 °C, g/L | pH Stability Range in Aqueous Solutions at 25 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Monocalcium phosphate monohydrate (MCPM) | Ca(H2PO4)2·H2O | 1.14 | ~18 | 0.0–2.0 |

| 0.5 | Monocalcium phosphate anhydrous (MCPA or MCP) | Ca(H2PO4)2 | 1.14 | ~17 | [c] |

| 1.0 | Dicalcium phosphate dihydrate (DCPD), mineral brushite | CaHPO4·2H2O | 6.59 | ~0.088 | 2.0–6.0 |

| 1.0 | Dicalcium phosphate anhydrous (DCPA or DCP), mineral monetite | CaHPO4 | 6.90 | ~0.048 | [c] |

| 1.33 | Octacalcium phosphate (OCP) | Ca8(HPO4)2(PO4)4·5H2O | 96.6 | ~0.0081 | 5.5–7.0 |

| 1.5 | α-Tricalcium phosphate (α-TCP) | α-Ca3(PO4)2 | 25.5 | ~0.0025 | [a] |

| 1.5 | β-Tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) | β-Ca3(PO4)2 | 28.9 | ~0.0005 | [a] |

| 1.2–2.2 | Amorphous calcium phosphates (ACP) | CaxHy(PO4)z·nH2O, n = 3–4.5; 15%–20% H2O | [b] | [b] | ~5–12 [d] |

| 1.5–1.67 | Calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite (CDHA or Ca-def HA) [e] | Ca10−x(HPO4)x(PO4)6−x(OH)2−x (0 < x < 1) | ~85 | ~0.0094 | 6.5–9.5 |

| 1.67 | Hydroxyapatite (HA, HAp or OHAp) | Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 | 116.8 | ~0.0003 | 9.5–12 |

| 1.67 | Fluorapatite (FA or FAp) | Ca10(PO4)6F2 | 120.0 | ~0.0002 | 7–12 |

| 1.67 | Oxyapatite (OA, OAp or OXA) [f], mineral voelckerite | Ca10(PO4)6O | ~69 | ~0.087 | [a] |

| 2.0 | Tetracalcium phosphate (TTCP or TetCP), mineral hilgenstockite | Ca4(PO4)2O | 38–44 | ~0.0007 | [a] |

- [a] These compounds cannot be precipitated from aqueous solutions.

- [b] Cannot be measured precisely. However, the following values were found: 25.7 ± 0.1 (pH = 7.40), 29.9 ± 0.1 (pH = 6.00), 32.7 ± 0.1 (pH = 5.28). The comparative extent of dissolution in acidic buffer is: ACP >> α-TCP >> β-TCP > CDHA >> HA > FA.

- [c] Stable at temperatures above 100 °C.

- [d] Always metastable.

- [e] Occasionally, it is called “precipitated HA (PHA)”.

- [f] Existence of OA remains questionable.

3.2. Polymers

| Polymer | Thermal Properties (°C) | Tensile Modulus (GРa) | Degradation Time (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| polyglycolic acid (PGA) | Tg = 35–40 | 7.06 | 6–12 (strength loss within 3 weeks) |

| Tm = 225–230 | |||

| L-polylactic acid (LPLA) | Tg = 60–65 | 2.7 | >24 |

| Tm = 173–178 | |||

| D,L-polylactic acid (DLPLA) | Tg = 55–60 | 1.9 | 12–16 |

| amorphous | |||

| 85/15 D,L-polylactic-co-glycolic acid (85/15 DLPLGA) | Tg = 50–55 | 2.0 | 5–6 |

| amorphous | |||

| 75/25 D,L-polylactic-co-glycolic acid (75/25 DLPLGA) | Tg = 50–55 | 2.0 | 4–5 |

| amorphous | |||

| 65/35 D,L-polylactic-co-glycolic acid (65/35 DLPLGA) | Tg = 45–50 | 2.0 | 3–4 |

| amorphous | |||

| 50/50 D,L-polylactic-co-glycolic acid (50/50 DLPLGA) | Tg = 45–50 | 2.0 | 1–2 |

| amorphous | |||

| poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Tg = (−60)–(−65) | 0.4 | >24 |

| Tm = 58–63 |

3.3. Inorganic Materials and Compounds

3.3.1. Metals

3.3.2. Glasses and Glass-Ceramics

3.3.3. Ceramics

3.3.4. Carbon

4. Biocomposites and Hybrid Biomaterials Containing CaPO4

- biocomposites with polymers;

- self-setting formulations;

- formulations based on nanodimensional CaPO4 and nanodimensional biocomposites;

- biocomposites with collagen;

- formulations with other bioorganic compounds and/or biological macromolecules;

- injectable bone substitutes (IBS);

- biocomposites with inorganic compounds, carbon and metals;

- functionally graded formulations;

- biosensors.

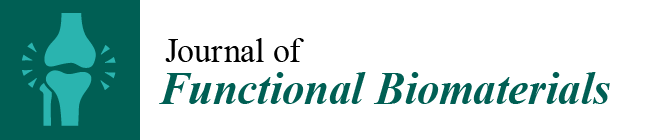

4.1. Biocomposites with Polymers

4.1.1. Apatite-Based Formulations

4.1.2. TCP-Based Formulations

4.1.3. Formulations Based on Other Types of CaPO4

4.2. Self-Setting Formulations

4.3. Formulations Based on Nanodimensional CaPO4 and Nanodimensional Biocomposites

4.4. Biocomposites with Collagen

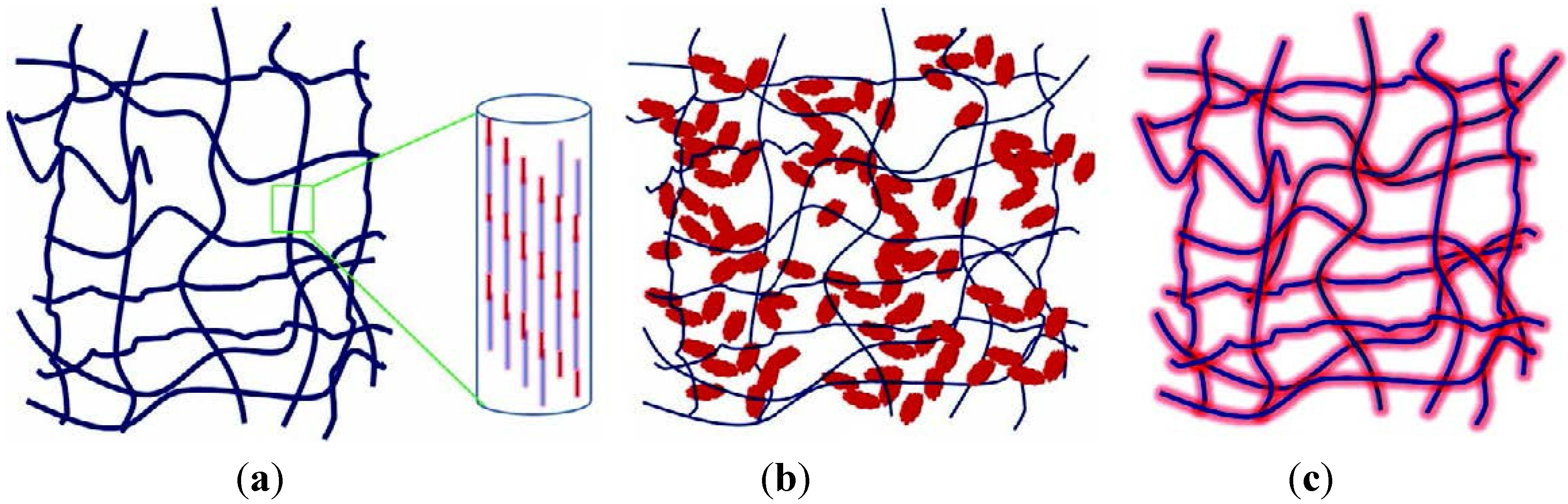

4.5. Formulations with Other Bioorganic Compounds

4.6. Injectable Bone Substitutes (IBS)

| Producer | Product name | Composition | Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApaTech (UK) | Actifuse™ | HA, polymer and aqueous solution | pre-mixed |

| Actifuse™ Shape; Actifuse™ ABX | Si-substituted CaPO4 and a polymer | pre-mixed | |

| Baxter (US) | TricOs Τ; TricOs | BCP (60% HA, 40% β-TCP) granules and Tissucol (fibrin glue) | to be mixed |

| Berkeley Advanced Biomaterials | Bi-Ostetic Putty | not disclosed | not disclosed |

| BioForm (US) | Calcium hydroxylapatite implant | HA powder embedded in a mixture of glycerine, water and CMC | pre-mixed |

| Biomatlante (FR) | In’Oss™ | BCP granules (60% HA, 40% β-TCP; 0.08–0.2 mm) and 2% HPMC | pre-mixed |

| MBCP Gel® | BCP granules (60% HA, 40% β-TCP; 0.08–0.2 mm) and 2% HPMC | pre-mixed | |

| Hydr’Os | BCP granules (60% HA, 40% β-TCP; micro- and nano-sized particles) and saline solution | pre-mixed | |

| Degradable solutions (CH) | Easy graft™ | β-TCP or BCP granules (0.45–l.0 mm) coated with 10 μm PLGA, N-methyl-2-pyrrolydone | to be mixed |

| Dentsply (US) | Pepgen P-15® flow | HA (0.25–0.42 mm), P-15 peptide and aqueous Na hyaluronate solution | to be mixed |

| DePuy Spine (US) | Healos® Fx | HA (20%–30%) and collagen | to be mixed |

| Fluidinova (P) | nanoXIM TCP | β-TCP (5% or 15%) and water | pre-mixed |

| nanoXIM HA | HA (5%, 15%, 30% or 40%) and water | pre-mixed | |

| Integra LifeSciences (US) | Mozaik Osteoconductive Scaffold | β-TCP (80%) and type 1 collagen (20%) | to be mixed |

| Mathys Ltd (CH) | Ceros® Putty/cyclOS® Putty | β-TCP granules (0.125–0.71 mm; 94%) and recombinant Na hyaluronate powder (6%) | to be mixed |

| Medtronic (US) | Mastergraft® | BCP (85% HA, 15% β-TCP) and bovine collagen | to be mixed |

| Merz Aesthetics (GER) | RADIESSE® | HA particles suspended in a gel | pre-mixed |

| Osartis / ΑΑΡ (GER) | Ostim® | Nanocrystalline HA (35%) and water (65%) | pre-mixed |

| Smith & Nephew (US) | JAXTCP | β-TCP granules and an aqueous solution of 1.75% CMC and 10% glycerol | to be mixed |

| Stryker (US) | Calstrux™ | β-TCP granules and CMC | to be mixed |

| Teknimed (FR) | Nanogel | HA (100 – 200 nm) (30%) and water (70%) | pre-mixed |

| Therics (US) | Therigraft™ Putty | β-TCP granules and polymer | pre-mixed |

| Zimmer (US) | Collagraft | BCP granules (65% HA, 35% β-TCP; 0.5–1.0 mm), bovine collagen and bone marrow aspirate | to be mixed |

4.7. Biocomposites with Inorganic Compounds, Carbon and Metals

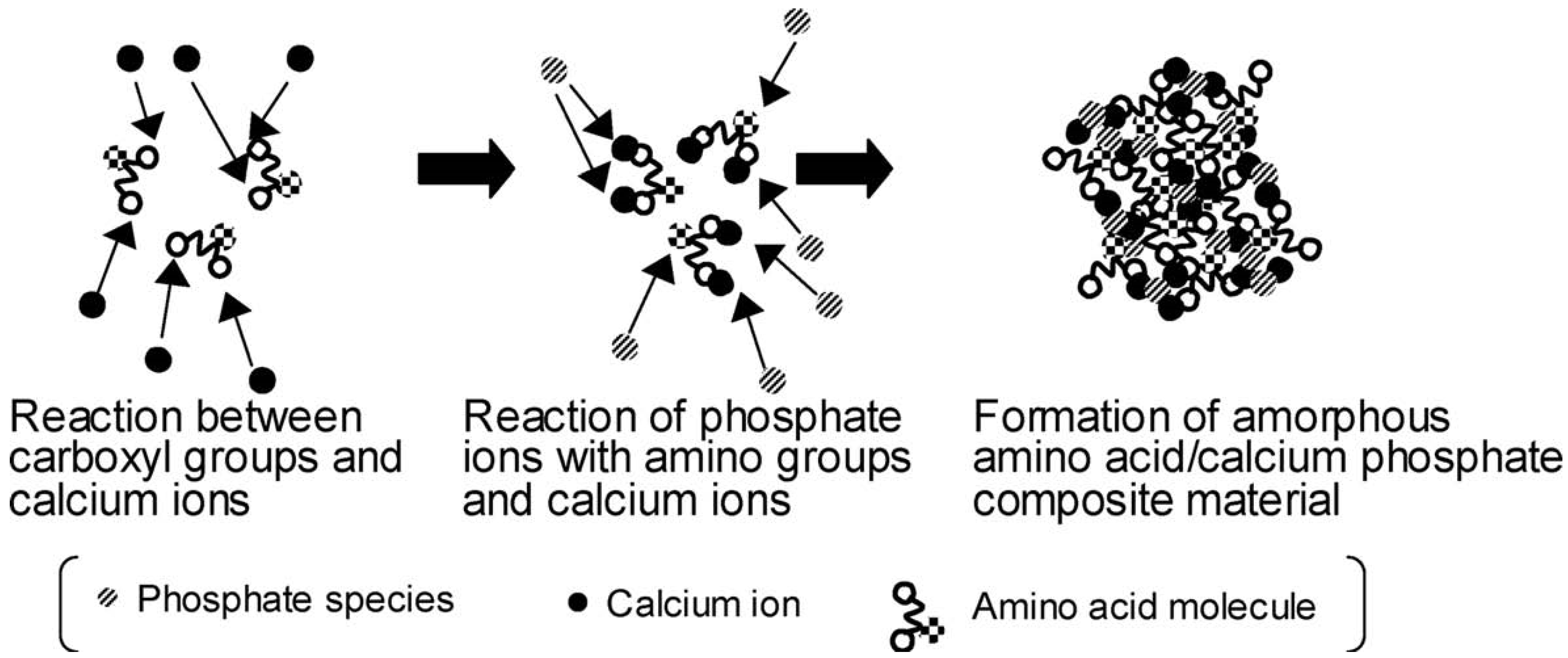

4.8. Functionally Graded Formulations

4.9. Biosensors

5. Interactions among the Phases

6. Bioactivity and Biodegradation

7. Some Challenges and Critical Issues

- There are not enough reliable experimental and clinical data supporting the long-term performance of biocomposites with respect to monolithic traditional materials;

- The design of biocomposites and hybrid biomaterials is far more complex than that of conventional monolithic materials because of the large number of additional design variables to be considered;

- The available fabrication methods may limit the possible reinforcement configurations, may be time consuming, expensive, highly skilled and may require special cleaning and sterilization processes;

- There are no satisfactory standards yet for biocompatibility testing of the biocomposite implants because the ways in which the components of any biocomposite interact to living tissues are not completely understood;

- There are no adequate standards for the assessment of biocomposite fatigue performance because the fatigue behavior of such materials is far more complex and difficult to predict than that of traditional materials [197].

- Optimizing biocomposite processing conditions;

- Optimization of interfacial bonding and strength equivalent to natural bone;

- Optimization of the surface properties and pore size to maximize bone growth;

- Maintaining the adequate volume of the construct in vivo to allow bone formation to take place;

- Withstanding the load-bearing conditions;

- Matching the bioresorbability of the grafts and their biomechanical properties while forming new bone;

- Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which the cells and the biocomposite matrix interact with each other in vivo to promote bone regeneration;

- Supporting angiogenesis and vascularization for the growth of healthy bone cells and subsequent tissue formation and remodeling.

8. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-W | apatite-wollastonite |

| BMP | bone morphogenetic protein |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CMC | carboxymethylcellulose |

| EVOH | a copolymer of ethylene and vinyl alcohol |

| IBS | injectable bone substitute |

| HDPE | high-density polyethylene |

| HPMC | hydroxypropylmethylcellulose |

| PA | polyamide |

| PAA | polyacrylic acid |

| PBT | polybutyleneterephthalate |

| PCL | poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| PDLLA | poly(D,L-lactic acid) |

| PE | polyethylene |

| PEEK | polyetheretherketone |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PGA | polyglycolic acid |

| PHB | polyhydroxybutyrate |

| PHBHV | poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) |

| PHEMA | polyhydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid |

| PLGC | co-polyester lactide-co-glycolide-co-ε-caprolactone |

| PLLA | poly(L-lactic acid) |

| PMMA | polymethylmethacrylate |

| PP | polypropylene |

| PPF | poly(propylene-co-fumarate) |

| PSZ | partially stabilized zirconia |

| PTMC | poly(trimethylene carbonate) |

| PU | polyurethane |

| PVA | polyvinyl alcohol |

| PVAP | polyvinyl alcohol phosphate |

| SEVA-C | a blend of EVOH with starch |

References

- Chau, A.M.T.; Mobbs, R.J. Bone graft substitutes in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaveh, K.; Ibrahim, R.; Bakar, M.Z.A.; Ibrahim, T.A. Bone grafting and bone graft substitutes. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2010, 9, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, N.; Jupiter, D.C. Bone graft substitute: allograft and xenograft. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2015, 32, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.D. Autograft and nonunions: morbidity with intramedullary bone graft versus iliac crest bone graft. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2010, 41, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Cui, W.; Zhao, J.; Su, W. A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials comparing hamstring autografts versus bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2012, 132, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, E.E.; Triplett, W.W. Iliac crest bone grafting: review of 160 consecutive cases. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 45, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, H.; Lendeckel, S.; Howaldt, H.P.; Streckbein, P. Donor site morbidity after bone harvesting from the anterior iliac crest. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 109, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, A.; Gorst-Rasmussen, A.; Jensen, T. Donor site morbidity associated with autogenous bone harvesting from the ascending mandibular ramus. Implant Dent. 2013, 22, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qvick, L.M.; Ritter, C.A.; Mutty, C.E.; Rohrbacher, B.J.; Buyea, C.M.; Anders, M.J. Donor site morbidity with reamer-irrigator-aspirator (RIA) use for autogenous bone graft harvesting in a single centre 204 case series. Injury 2013, 44, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Kawashita, M. Current progress in inorganic artificial biomaterials. J. Artif. Organ. 2011, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojar, W.; Kucharska, M.; Ciach, T.; Koperski, Ł.; Jastrzębski, Z.; Szałwiński, M. Bone regeneration potential of the new chitosan-based alloplastic biomaterial. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 28, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchbhavi, V.K. Synthetic bone grafting in foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Clin. 2010, 15, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinopoulos, H.; Dimitriou, R.; Giannoudis, P.V. Bone graft substitutes: What are the options? Surgeon 2012, 10, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, S.; Wagner, H.D. The material bone: structure-mechanical function relations. Ann. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998, 28, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, C.; Combes, C.; Drouet, C.; Glimcher, M.J. Bone mineral: update on chemical composition and structure. Osteoporos. Int. 2009, 20, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium Orthophosphates: Applications in Nature, Biology, and Medicine; Pan Stanford: Singapore, 2012; p. 854. [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate-based bioceramics. Materials 2013, 6, 3840–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, D.B. The contribution of the organic matrix to bone’s material properties. Bone 2002, 31, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzl, P.; Gupta, H.S.; Paschalis, E.P.; Roschger, P. Structure and mechanical quality of the collagen-mineral nano-composite in bone. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14, 2115–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszta, M.J.; Cheng, X.G.; Jee, S.S.; Kumar, B.R.; Kim, Y.Y.; Kaufman, M.J.; Douglas, E.P.; Gower, L.B. Bone structure and formation: a new perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2007, 58, 77–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, H.; Moreira-Gonçalves, D.; Coriolano, H.J.A.; Duarte, J.A. Bone quality: The determinants of bone strength and fragility. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, R.; Ramakrishna, S. Development of nanocomposites for bone grafting. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 2385–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanek, W.; Yoshimura, M. Processing and properties of hydroxyapatite-based biomaterials for use as hard tissue replacement implants. J. Mater. Res. 1998, 13, 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Regi, M.; Arcos, D. Nanostructured hybrid materials for bone tissue regeneration. Curr. Nanosci. 2006, 2, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblaré, M.; Garcia, J.M.; Gómez, M.J. Modelling bone tissue fracture and healing: a review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2004, 71, 1809–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Regi, M. Revisiting ceramics for medical applications. Dalton Trans. 2006, 5211–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pioletti, D.P. Biomechanics in bone tissue engineering. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2010, 13, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huiskes, R.; Ruimerman, R.; van Lenthe, H.G.; Janssen, J.D. Effects of mechanical forces on maintenance and adaptation of form in trabecular bone. Nature 2000, 405, 704–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccaccini, A.R.; Blaker, J.J. Bioactive composite materials for tissue engineering scaffolds. Expert Rev. Med. Dev. 2005, 2, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutmacher, D.W.; Schantz, J.T.; Lam, C.X.F.; Tan, K.C.; Lim, T.C. State of the art and future directions of scaffold-based bone engineering from a biomaterials perspective. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2007, 1, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarino, V.; Causa, F.; Ambrosio, L. Bioactive scaffolds for bone and ligament tissue. Expert Rev. Med. Dev. 2007, 4, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunos, D.M.; Bretcanu, O.; Boccaccini, A.R. Polymer-bioceramic composites for tissue engineering scaffolds. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 4433–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.X. Progress of study on drug-loaded chitosan/hydroxyapatite composite in bone tissue engineering. J. Funct. Mater. 2014, 45, 13006–13012, 13020. [Google Scholar]

- Hench, L.L.; Polak, J.M. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science 2002, 295, 1014–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathijsen, A. Nieuwe Wijze van Aanwending van het Gips-Verband bij Beenbreuken; J.B. van Loghem: Haarlem, The Netherlands, 1852; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Dreesman, H. Über Knochenplombierung. Beitr. Klin. Chir. 1892, 9, 804–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Developing bioactive composite materials for tissue replacement. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2133–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Composite material. Available online: http:/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composite_material (assessed on 16 June 2015).

- Gibson, R.F. A review of recent research on mechanics of multifunctional composite materials and structures. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 2793–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.L.; Gregson, P.J. Composite technology in load-bearing orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.Z.; Hong, L.; Jia, S.R.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Jiang, H.J. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite-bacterial cellulose nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.Z.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, C.D.; Raman, S.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H.J.; He, F.; Gao, C. Biomimetic synthesis of hydroxyapatite/bacterial cellulose nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2007, 27, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuki, C.; Kamitakahara, M.; Miyazaki, T. Coating bone-like apatite onto organic substrates using solutions mimicking body fluid. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2007, 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyane, A. Development of apatite-based composites by a biomimetic process for biomedical applications. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 118, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate deposits: preparation, properties and biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 55, 272–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surmenev, R.A.; Surmeneva, M.A.; Ivanova, A.A. Significance of calcium phosphate coatings for the enhancement of new bone osteogenesis—A review. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphate coatings on magnesium and its biodegradable alloys. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 2919–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, L.Y.; Yang, X.B.; Weng, J. Preparation of bioactive porous HA/PCL composite scaffolds. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 2942–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.; Ajaal, T. Toughening of porous bioceramic scaffolds by bioresorbable polymeric coatings. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 2009, 223, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, A.S.; Jang, J.L.; Liberman, R.F.; Weinzweig, J. Creation of a vascularized composite graft with acellular dermal matrix and hydroxyapatite. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Duan, K.; Zhang, J.W.; Lu, X.; Weng, J. The influence of polymer concentrations on the structure and mechanical properties of porous polycaprolactone-coated hydroxyapatite scaffolds. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 4586–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Uemura, T.; Kojima, H.; Kikuchi, M.; Tanaka, J.; Tateishi, T. Application of low-pressure system to sustain in vivo bone formation in osteoblast/porous hydroxyapatite composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2001, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbo, I.R.; Bronckers, A.L.J.J.; de Lange, G.; Burger, E.H. Localisation of osteogenic and osteoclastic cells in porous β-tricalcium phosphate particles used for human maxillary sinus floor elevation. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikán, J.; Villamil, M.; Montes, T.; Carretero, C.; Bernal, C.; Torres, M.L.; Zakaria, F.A. Porcine model for hybrid material of carbonated apatite and osteoprogenitor cells. Mater. Res. Innov. 2009, 13, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, K.; Miwa, M.; Nagamune, K.; Sakai, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Niikura, T.; Iwakura, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Shibanuma, N.; Hata, Y.; et al. Nondestructive evaluation of cell numbers in bone marrow stromal cell/β-tricalcium phosphate composites using ultrasound. Tissue Eng. C 2010, 16, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krout, A.; Wen, H.B.; Hippensteel, E.; Li, P. A hybrid coating of biomimetic apatite and osteocalcin. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 73, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, B.; Soundrapandian, C.; Nandi, S.K.; Mukherjee, P.; Dandapat, N.; Roy, S.; Datta, B.K.; Mandal, T.K.; Basu, D.; Bhattacharya, R.N. Development of new localized drug delivery system based on ceftriaxone-sulbactam composite drug impregnated porous hydroxyapatite: a systematic approach for in vitro and in vivo animal trial. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 1659–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickelbick, G. Hybrid Materials. Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2007; p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, F.L.; Rawlings, R.D. Composite Materials: Engineering and Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; p. 480. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z.; Riester, L.; Curtin, W.A.; Li, H.; Sheldon, B.W.; Liang, J.; Chang, B.; Xu, J.M. Direct observation of toughening mechanisms in carbon nanotube ceramic matrix composites. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.I.B.; Ferreira, O.; Preto, M.; Miguez, E.; Soares, I.L.; da Silva, E.P. Evaluation of composites miscibility by low field NMR. Int. J. Polym. Mater. 2007, 56, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, E. Polymer miscibility, phase separation, morphological modifications and polymorphic transformations in dense fluids. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2009, 47, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šupová, M. Problem of hydroxyapatite dispersion in polymer matrices: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009, 20, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böstman, O.; Pihlajamäki, H. Clinical biocompatibility of biodegradable orthopaedic implants for internal fixation: A review. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.J.; Thomas, S. Biofibres and biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, S.M.; Bonfield, W. Biocomposites for medical applications. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 40, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, K.E. Bioactive ceramic-reinforced composites for bone augmentation. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, S541–S557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravitis, Y.A.; Tééyaér, R.E.; Kallavus, U.L.; Andersons, B.A.; Ozol’-Kalnin, V.G.; Kokorevich, A.G.; Érin’sh, P.P.; Veveris, G.P. Biocomposite structure of wood cell membranes and their destruction by explosive autohydrolysis. Mech. Compos. Mater. 1987, 22, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.L.; Picha, G.J. The use of coralline hydroxyapatite in a ‘biocomposite’ free flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1991, 87, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium orthophosphates and human beings. A historical perspective from the 1770s until 1940. Biomatter 2012, 2, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. A detailed history of calcium orthophosphates from 1770s till 1950. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 3085–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hing, K.A. Bioceramic bone graft substitutes: influence of porosity and chemistry. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2005, 2, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Naqshbandi, A.; Sopyan, I.; Gunawan. Development of porous calcium phosphate bioceramics for bone implant applications: a review. Rec. Pat. Mater. Sci. 2013, 6, 238–252. [Google Scholar]

- LeGeros, R.Z. Calcium Phosphates in Oral Biology and Medicine. In Monographs in Oral Science; Myers, H.M., Ed.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 1991; Volume 15, p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.C. Structure and Chemistry of the Apatites and Other Calcium Orthophosphates. In Studies in Inorganic Chemistry; Agrawal, P.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 18, p. 389. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, Z. Calcium Phosphates in Biological and Industrial Systems; Kluwer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; p. 529. [Google Scholar]

- Heimann, R.B. Calcium Phosphate: Structure, Synthesis, Properties, and Applications; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- Gshalaev, V.S.; Demirchan, A.C. Hydroxyapatite: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 477. [Google Scholar]

- Carraher, C.E., Jr. Introduction to Polymer Chemistry, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- Young, R.J.; Lovell, P.A. Introduction to Polymers, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; p. 688. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, R.C.; Ak, S.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Mikos, A.G. Polymer Scaffold Processing. In Principles of Tissue Engineering; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Mayer, J.; Wintermantel, E.; Leong, K.W. Biomedical applications of polymer-composite materials: A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1189–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, V.P. Non-degradable biocompatible polymers in medicine: past, present and future. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2003, 4, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yuan, L.; Song, W.; Wu, Z.; Li, D. Biocompatible polymer materials: Role of protein-surface interactions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 1059–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Sato, K.; Kitakami, E.; Kobayashi, S.; Hoshiba, T.; Fukushima, K. Design of biocompatible and biodegradable polymers based on intermediate water concept. Polymer J. 2015, 47, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, R.P.; Hayes, J.L.; Chick, W.L. Encapsulated cell technology. Nature Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.C.; Singh, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Mishra, A. Review on production and medical applications of ɛ-polylysine. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 65, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C.M.; Ray, R.B. Biodegradable polymeric scaffolds for musculoskeletal tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 55, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, H.; Yoo, M.; Park, I.; Kim, T.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Oh, J.; Akaike, T.; Cho, C. A novel degradable polycaprolactone network for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Zhang, P.H. Electrospun absorbable polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds for medical applications. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 906, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, S.; Chiono, V.; Tonda-Turo, C.; Mattu, C.; Gianluca, C. Biomimetic polyurethanes in nano and regenerative medicine. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 5128–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temenoff, J.S.; Mikos, A.G. Injectable biodegradable materials for orthopedic tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2405–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behravesh, E.; Yasko, A.W.; Engel, P.S.; Mikos, A.G. Synthetic biodegradable polymers for orthopaedic applications. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1999, 367, S118–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, K.U.; Gresser, J.D.; Wise, D.L.; White, R.L.; Trantolo, D.J. Osteoconductivity of an injectable and bioresorbable poly(propyleneglycol-co-fumaric acid) bone cement. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Wang, S.; Fox, B.C.; Ritman, E.L.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Lu, L. Poly(propylene fumarate) bone tissue engineering scaffold fabrication using stereolithography: effects of resin formulations and laser parameters. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Feng, E.; Song, J. Renaissance of aliphatic polycarbonates: New techniques and biomedical applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 39822:1–39822:16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, E.D.; Coleman, B.D.; Barnes, C.P.; Simpson, D.G.; Wnek, G.E.; Bowlin, G.L. Electrospinning polydioxanone for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2005, 1, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.L. Acrylics in Biomedical Engineering. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, R.Q.; Byron, R.T.; Osborne, P.B.; West, K.P. PMMA: An essential material in medicine and dentistry. J. Long-Term Eff. Med. Implants 2005, 15, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.W.; Leong, J.C.Y.; Lu, W.W.; Luk, K.D.K.; Cheung, K.M.C.; Chiu, K.Y.; Chow, S.P. A novel injectable bioactive bone cement for spinal surgery: A developmental and preclinical study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 52, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckellop, H.; Shen, F.; Lu, B.; Campbell, P.; Salovey, R. Development of an extremely wear resistant UHMW polyethylene for total hip replacements. J. Orthop. Res. 1999, 17, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, S.M.; Muratoglu, O.K.; Evans, M.; Edidin, A.A. Advances in the processing, sterilization and crosslinking of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene for total joint arthroplasty. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 1659–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurencin, C.T.; Ambrosio, M.A.; Borden, M.D.; Cooper, J.A., Jr. Tissue engineering: Orthopedic applications. Ann. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1999, 1, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, G.J.; Cune, M.S.; van Dooren, M.; de Putter, C.; van Blitterswijk, C.A. A comparative study of flexible (Polyactive™) versus rigid (hydroxylapatite) permucosal dental implants. I. Clinical aspects. J. Oral Rehabil. 1997, 24, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, G.J.; Dalmeijer, R.A.; de Putter, C.; van Blitterswijk, C.A. A comparative study of flexible (Polyactive™) versus rigid (hydroxylapatite) permucosal dental implants. II. Histological aspects. J. Oral Rehabil. 1997, 24, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waris, E.; Ashammakhi, N.; Lehtimäki, M.; Tulamo, R.M.; Törmälä, P.; Kellomäki, M.; Konttinen, Y.T. Long-term bone tissue reaction to polyethylene oxide/polybutylene terephthalate copolymer (Polyactive®) in metacarpophalangeal joint reconstruction. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2509–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, A.; Nicklasson, E.; Harrah, T.; Panilaitis, B.; Kaplan, D.L.; Brittberg, M.; Gatenholm, P. Bacterial cellulose as a potential scaffold for tissue engineering of cartilage. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampinelli, G.; di Landro, L.; Fujii, T. Characterization of biomaterials based on microfibrillated cellulose with different modifications. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, P.L.; Barbosa, M.A.; Pouysége, L.; de Jéso, B.; Rouais, F.; Baquuey, C. Cellulose phosphates as biomaterials. Mineralization of chemically modified regenerated cellulose hydrogels. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 2163–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, P.L.; Jéso, B.D.; Bareille, R.; Rouais, F.; Baquey, C.; Barbosa, M.A. Cellulose phosphates as biomaterials. In vitro biocompatibility studies. React. Funct. Polym. 2006, 66, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.; Dean, D.R.; Vohra, Y.K. Nanostructured biomaterials for regenerative medicine. Curr. Nanosci. 2006, 2, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, K.C.; Bizios, R. Mini-review: Proactive biomaterials and bone tissue engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996, 50, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashammakhi, N.; Rokkanen, P. Absorbable polyglycolide devices in trauma and bone surgery. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyan, B.; Lohmann, C.; Somers, A.; Neiderauer, G.; Wozney, J.; Dean, D.; Carnes, D.; Schwartz, Z. Potential of porous poly-D,L-lactide-co-glycolide particles as a carrier for recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 during osteoinduction in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 46, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, J.O.; Leong, K. Poly(α-hydroxyacids): Carriers for bone morphogenetic proteins. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, L.G. Polymeric biomaterials. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.J.; Miller, M.J.; Yasko, A.W.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Mikos, A.G. Polymer concepts in tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishuang, S.L.; Payne, R.G.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Aufdemorte, T.B.; Bizios, R.; Mikos, A.G. Osteoblast migration on poly(α-hydroxy esters). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1996, 50, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Shikinami, Y.; Okuno, M. Bioresorbable devices made of forged composites of hydroxyapatite (HA) particles and poly-L-lactide (PLLA): Part I. Basic characteristics. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, E.; Lim, L.Y. Implantable applications of chitin and chitosan. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, A.; Sittinger, M.; Risbud, M.V. Chitosan: A versatile biopolymer for orthopaedic tissue-engineering. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5983–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskin, E.; Bölgen, N.; Egri, S.; Isoglu, I.A. Electrospun matrices made of poly(α-hydroxy acids) for medical use. Nanomedicine 2007, 2, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezwana, K.; Chena, Q.Z.; Blakera, J.J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, B.L.; Otero, T.C.; Panitch, A. Polymeric biomaterials for tissue and organ regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2001, 34, 147–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, J.F.; Sousa, R.A.; Boesel, L.F.; Neves, N.M.; Reis, R.L. Bioinert, biodegradable and injectable polymeric matrix composites for hard tissue replacement: state of the art and recent developments. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 789–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Middleton, J.; Tipton, A. Synthetic biodegradable polymers as orthopedic devices. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, A.G.; Meikle, M.C. Resorbable synthetic polymers as replacements for bone graft. Clin. Mater. 2004, 17, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Heras Alarcón, C.; Pennadam, S.; Alexander, C. Stimuli responsive polymers for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohane, D.S.; Langer, R. Polymeric biomaterials in tissue engineering. Pediatric Res. 2008, 63, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M. Chemical syntheses of biodegradable polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 87–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Jacob, K.I.; Tannenbaum, R.; Sharaf, M.A.; Jasiuk, I. Experimental trends in polymer nanocomposites—A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 393, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, P.K.; Ding, C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2004, 47, 49–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, T. Biofunctionalization of titanium for dental implant. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2010, 46, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosch, K.H.; Stürmer, K.M. Metallic biomaterials in skeletal repair. Eur. J. Trauma 2006, 32, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, M.B.; Hassan, M.R.; Sahari, B.B. Metallic biomaterials of knee and hip—A review. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organ. 2010, 24, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.; Pandit, A.; Apatsidis, D.P. Fabrication methods of porous metals for use in orthopaedic applications. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B. A new era in porous metals: applications in orthopaedics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, M. Fabrication methods of porous tantalum metal implants for use as biomaterials. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 476–478, 2063–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.X. Biomimetic materials for tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2008, 60, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathuria, Y.P. The potential of biocompatible metallic stents and preventing restenosis. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 417, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnama, A.; Hermawan, H.; Couet, J.; Mantovani, D. Assessing the biocompatibility of degradable metallic materials: State-of-the-art and focus on the potential of genetic regulation. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.; Shadanbaz, S.; Woodfield, T.B.F.; Staiger, M.P.; Dias, G.J. Magnesium biomaterials for orthopedic application: a review from a biological perspective. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2014, 102, 1316–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, J.C. Phosphate based glasses for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 2395–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilocca, A. Current challenges in atomistic simulations of glasses for biomedical applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 3874–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuga, T. Development of phosphate glass-ceramics for biomedical applications. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 115, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, A.M.; El Batal, F.H.; El Batal, H.A. Zinc containing borate glasses and glass-ceramics: Search for biomedical applications. Process. Appl. Ceram. 2014, 8, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L. Bioceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998, 81, 1705–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L. The story of Bioglass®. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006, 17, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.R. Review of bioactive glass: From Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 4457–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weizhong, Y.; Dali, Z.; Guangfu, Y. Research and development of A-W bioactive glass ceramic. J. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 20, 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhou, D.; Xue, M.; Yang, W.; Long, Q.; Cao, B.; Feng, D. Study on the surface bioactivity of novel magnetic A-W glass ceramic in vitro. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höland, W.; Schweiger, M.; Watzke, R.; Peschke, A.; Kappert, H. Ceramics as biomaterials for dental restoration. Expert Rev. Med. Dev. 2008, 5, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.W.K.; Chow, T.W.; Matinlinna, J.P. Ceramic dental biomaterials and CAD/CAM technology: State of the art. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2014, 58, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, T.R.; Gangaiah, M.; Harish, P.V.; Krishnakumar, U.; Nandakishore, B. Zirconia ceramics as a dental biomaterial—An over view. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 2012, 26, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H.; Wang, M.C.; Du, J.K.; Sie, Y.Y.; Hsi, C.S.; Lee, H.E. Phase transformation and nanocrystallite growth behavior of 2 mol% yttria-partially stabilized zirconia (2Y-PSZ) powders. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 5165–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvie, R.C. A personal history of the development of transformation toughened PSZ ceramics. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 50, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, J. Elemental carbon as a biomaterial. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1972, 5, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olborska, A.; Swider, M.; Wolowiec, R.; Niedzielski, P.; Rylski, A.; Mitura, S. Amorphous carbon – biomaterial for implant coatings. Diamond Relat. Mater. 1994, 3, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N.; Usui, Y.; Aoki, K.; Narita, N.; Shimizu, M.; Hara, K.; Ogiwara, N.; Nakamura, K.; Ishigaki, N.; Kato, H.; et al. Carbon nanotubes: biomaterial applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1897–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, N.; Haniu, H.; Usui, Y.; Aoki, K.; Hara, K.; Takanashi, S.; Shimizu, M.; Narita, N.; Okamoto, M.; Kobayashi, S.; et al. Safe clinical use of carbon nanotubes as innovative biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6040–6079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlopek, J.; Czajkowska, B.; Szaraniec, B.; Frackowiak, E.; Szostak, K.; Beguin, F. In vitro studies of carbon nanotubes biocompatibility. Carbon 2006, 44, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, N.; Usui, Y.; Aoki, K.; Narita, N.; Shimizu, M.; Ogiwara, N.; Nakamura, K.; Ishigaki, N.; Kato, H.; Taruta, S. Carbon nanotubes for biomaterials in contact with bone. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Kahn, M.G.C.; Wong, S.S. Rational chemical strategies for carbon nanotube functionalization. Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9, 1898–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuvelot, J.; Bergeret, C.; Mallet, R.; Fernandez, V.; Cousseau, J.; Baslé, M.F.; Chappard, D. In vitro calcification of chemically functionalized carbon nanotubes. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4110–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Y.; Gong, T.; Zhou, S. The functionalization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes by in situ deposition of hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5182–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converse, G.L.; Yue, W.; Roeder, R.K. Processing and tensile properties of hydroxyapatite-whisker-reinforced polyetheretherketone. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Converse, G.L.; Roeder, R.K. Tensile properties of hydroxyapatite whisker reinforced polyetheretherketone. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2005, 898, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Kim, H.E.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, U.C.; Kim, J.H.; Koh, Y.H. Production and characterization of calcium phosphate (CaP) whisker-reinforced poly(ε-caprolactone) composites as bone regenerative. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2010, 30, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Darvell, B.W. Failure and behavior in water of hydroxyapatite whisker-reinforced bis-GMA-based resin composites. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 10, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wang, R.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, M. Polymer grafted hydroxyapatite whisker as a filler for dental composite resin with enhanced physical and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 4994–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.W.; Bao, S.; Jin, Y.; Jiang, X.Z.; Zhu, M.F. Novel bionic dental resin composite reinforced by hydroxyapatite whisker. Mater. Res. Innov. 2014, 18, S4854–S4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri-Felekori, M.; Mesgar, A.S.M.; Mohammadi, Z. Development of composite scaffolds in the system of gelatin—Calcium phosphate whiskers/fibrous spherulites for bone tissue engineering. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 6013–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Ban, S.; Ito, T.; Tsuruta, S.; Kawai, T.; Nakamura, H. Biocompatibility of composite membrane consisting of oriented needle-like apatite and biodegradable copolymer with soft and hard tissues in rats. Dental Mater. J. 2004, 23, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y. Photo-crosslinking polymerization to prepare polyanhydride/needle-like hydroxyapatite biodegradable nanocomposite for orthopedic application. Mater. Lett. 2003, 57, 2848–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, E.; Firouzdor, V.; Eslaminejad, M.B.; Bagheri, F. Needle-like nano hydroxyapatite/poly(L-lactide acid) composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.P.; Wei, M.; Olson, J.R.; Shaw, M.T. A modified pultrusion process for preparing composites reinforced with continuous fibers and aligned hydroxyapatite nano needles. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, T.; Ota, Y.; Nogami, M.; Abe, Y. Preparation and mechanical properties of polylactic acid composites containing hydroxyapatite fibers. Biomaterials 2000, 22, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Ceramic-plastic material as a bone substitute. Arch. Surg. 1963, 87, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfield, W.; Grynpas, M.D.; Tully, A.E.; Bowman, J.; Abram, J. Hydroxyapatite reinforced polyethylene—A mechanically compatible implant material for bone replacement. Biomaterials 1981, 2, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, W.; Bowman, J.; Grynpas, M.D. Composite material for use in orthopaedics. UK Patent 8032647, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfield, W. Composites for bone replacement. J. Biomed. Eng. 1988, 10, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guild, F.J.; Bonfield, W. Predictive character of hydroxyapatite-polyethelene HAPEX™ composite. Biomaterials 1993, 14, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; di Silvio, L.; Wang, M.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. In vitro mechanical and biological assessment of hydroxyapatite-reinforced polyethylene composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1997, 8, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Joseph, R.; Bonfield, W. Hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composites for bone substitution: effect of ceramic particle size and morphology. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladizesky, N.H.; Ward, I.M.; Bonfield, W. Hydroxyapatite/high-performance polyethylene fiber composites for high load bearing bone replacement materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 65, 1865–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazhat, S.N.; Joseph, R.; Wang, M.; Smith, R.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Dynamic mechanical characterisation of hydroxyapatite reinforced polyethylene: effect of particle size. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2000, 11, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guild, F.J.; Bonfield, W. Predictive modelling of the mechanical properties and failure processes of hydroxyapatite-polyethylene (HAPEX™) composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1998, 9, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ladizesky, N.H.; Tanner, K.E.; Ward, I.M.; Bonfield, W. Hydrostatically extruded HAPEX™. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- That, P.T.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Fatigue characterization of a hydroxyapatite-reinforced polyethylene composite. I. Uniaxial fatigue. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- That, P.T.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Fatigue characterization of a hydroxyapatite-reinforced polyethylene composite. II. Biaxial fatigue. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, M.; Saunders, L.S.; Ward, I.M.; Davies, G.W.; Wang, M.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Anisotropic mechanical properties of oriented HAPEX™. J. Mater. Sci. 2002, 37, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvio, L.; Dalby, M.J.; Bonfield, W. Osteoblast behaviour on HA/PE composite surfaces with different HA volumes. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, M.J.; Kayser, M.V.; Bonfield, W.; di Silvio, L. Initial attachment of osteoblasts to an optimised HAPEX™ topography. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tanner, K.E.; Gurav, N.; di Silvio, L. In vitro osteoblastic response to 30 vol% hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 81, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, S.M.; Brooks, R.A.; Schneider, A.; Best, S.M.; Bonfield, W. Osteoblast-like cell response to bioactive composites-surface-topography and composition effects. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2004, 70, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salernitano, E.; Migliaresi, C. Composite materials for biomedical applications: A review. J. Appl. Biomater. Biomech. 2003, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Jan, E.; Aswath, P.B. Physical and mechanical behavior of hot rolled HDPE/HA composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 3369–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, M.; Ward, I.M.; McGregor, W.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Hydroxyapatite/polypropylene composite: a novel bone substitute material. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2001, 20, 2049–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppakarn, N.; Sanmaung, S.; Ruksakulpiwa, Y.; Sutapun, W. Effect of surface modification on properties of natural hydroxyapatite/polypropylene composites. Key Eng. Mater. 2008, 361–363, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, M.; Bahrololoom, M.E. Formulating the effects of applied temperature and pressure of hot pressing process on the mechanical properties of polypropylene-hydroxyapatite bio-composites by response surface methodology. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 4621–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi, M.; Bahrololoom, M.E. Effect of polypropylene molecular weight, hydroxyapatite particle size, and Ringer’s solution on creep and impact behavior of polypropylene-surface treated hydroxyapatite biocomposites. J. Compos. Mater. 2011, 45, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.A.; Reis, R.L.; Cunha, A.M.; Bevis, M.J. Processing and properties of bone-analogue biodegradable and bioinert polymeric composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Deb, S.; Bonfield, W. Chemically coupled hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composites: processing and characterisation. Mater. Lett. 2000, 44, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bonfield, W. Chemically coupled hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composites: structure and properties. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaeigohar, S.S.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Khavandi, A.; Sadi, A.Y. In vitro biological evaluation of β-TCP/HDPE—A novel orthopedic composite: A survey using human osteoblast and fibroblast bone cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2008, 84A, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadi, A.Y.; Homaeigohar, S.SH.; Khavandi, A.R.; Javadpour, J. The effect of partially stabilized zirconia on the mechanical properties of the hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, S.; Bodhak, S.; Basu, B. HDPE-Al2O3-HAp composites for biomedical applications: processing and characterizations. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 88, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, R.N.; Vardy, S.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Hydroxyapatite-polyethylene composite in orbital surgery. Bioceramics 1991, 4, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Dornhoffer, H.L. Hearing results with the dornhoffer ossicular replacement prostheses. Laryngoscope 1998, 108, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, R.E.; Wang, M.; Beale, B.; Bonfield, W. HAPEX™ for otologic applications. Biomed. Eng. Appl. Basis Commun. 1999, 11, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. Novel bio-composite of hydroxyapatite reinforced polyamide and polyethylene: Composition and properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 452–453, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, A.P.; Ward, I.M.; Ukleja, P.; Weng, J. The role of pressure annealing in improving the stiffness of polyethylene/hydroxyapatite composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 3165–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.M.; Leng, Y.; Gao, P. Processing and mechanical properties of HA/UHMWPE nanocomposites. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3701–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.M.; Gao, P.; Leng, Y. High strength and bioactive hydroxyapatite nano-particles reinforced ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene. Composites B 2007, 38, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.M.; Leng, Y.; Gao, P. Processing of hydroxyapatite reinforced ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3471–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvin, T.P.; Seno, J.; Murukan, B.; Santhosh, A.A.; Sabu, T.; Weimin, Y.; Sri, B. Poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate)/calcium phosphate nanocomposites: thermo mechanical and gas permeability measurements. Polym. Composite 2010, 31, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.L.; Cunha, A.M.; Oliveira, M.J.; Campos, A.R.; Bevis, M.J. Relationship between processing and mechanical properties of injection molded high molecular mass polyethylene + hydroxyapatite composites. Mater. Res. Inn. 2001, 4, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.A.; Reis, R.L.; Cunha, A.M.; Bevis, M.J. Structure development and interfacial interactions in high-density polyethylene/hydroxyapatite (HDPE/HA) composites molded with preferred orientation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 2873–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsalehi, S.A.; Khavandi, A.; Mirdamadi, S.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Kalantari, S.M. Nanomechanical and tribological behavior of hydroxyapatite reinforced ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene nanocomposites for biomedical applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donners, J.J.J.M.; Nolte, R.J.M.; Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M. Dendrimer-based hydroxyapatite composites with remarkable materials properties. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, O.D.; Stepuk, A.; Mohn, D.; Luechinger, N.A.; Feldman, K.; Stark, W.J. Light-curable polymer/calcium phosphate nanocomposite glue for bone defect treatment. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 2704–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignjatovic, N.L.; Plavsic, M.; Miljkovic, M.S.; Zivkovic, L.M.; Uskokovic, D.P. Microstructural characteristics of calcium hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide based composites. J. Microsc. 1999, 196, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrtic, D.; Antonucci, J.M.; Eanes, E.D. Amorphous calcium phosphate-based bioactive polymeric composites for mineralized tissue regeneration. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2003, 108, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, S.C.; Heath, D.J.; Coombes, A.G.A.; Bock, N.; Textor, M.; Downes, S. Biodegradable polymer/hydroxyapatite composites: Surface analysis and initial attachment of human osteoblasts. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 55, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Planell, J.A. Bioactive composites based on calcium phosphates for bone regeneration. Key Eng. Mater. 2010, 441, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Ma, P.X. Porous poly(L-lactic acid)/apatite composites created by biomimetic process. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999, 45, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; de Wijn, J.R.; van Blitterswijk, C.A. Composite biomaterials with chemical bonding between hydroxyapatite filler particles and PEG/PBT copolymer matrix. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 40, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrai, P.; Guerra, G.D.; Tricoli, M.; Krajewski, A.; Ravaglioli, A.; Martinetti, R.; Dolcini, L.; Fini, M.; Scarano, A.; Piattelli, A. Periodontal membranes from composites of hydroxyapatite and bioresorbable block copolymers. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1999, 10, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, R.K.; Sproul, M.M.; Turner, C.H. Hydroxyapatite whiskers provide improved mechanical properties in reinforced polymer composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 67, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagoner Johnson, A.J.; Herschler, B.A. A review of the mechanical behavior of CaP and CaP/polymer composites for applications in bone replacement and repair. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutmacher, D.W. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, L.M.; Bourban, P.E.; Manson, J.A.E. Processing of homogeneous ceramic/polymer blends for bioresorbable composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redepenning, J.; Venkataraman, G.; Chen, J.; Stafford, N. Electrochemical preparation of chitosan/hydroxyapatite composite coatings on titanium substrates. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 66, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.H.; Tanaka, J. Synthesis of a hydroxyapatite/collagen/chondroitin sulfate nanocomposite by a novel precipitation method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzotti, G.; Asmus, S.M.F. Fracture behavior of hydroxyapatite/polymer interpenetrating network composites prepared by in situ polymerization process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 316, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weickmann, H.; Gurr, M.; Meincke, O.; Thomann, R.; Mülhaupt, R. A versatile solvent-free “one-pot” route to polymer nanocomposites and the in situ formation of calcium phosphate/layered silicate hybrid nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Bhattarai, S.R.; Bahadur, K.C.R.; Khil, M.S.; Lee, D.R.; Kim, H.Y. Carbon nanotubes assisted biomimetic synthesis of hydroxyapatite from simulated body fluid. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 426, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealley, C.; Ben-Nissan, B.; van Riessen, A.; Elcombe, M. Development of carbon nanotube reinforced hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Key Eng. Mater. 2006, 309–311, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealley, C.; Elcombe, M.; van Riessen, A.; Ben-Nissan, B. Development of carbon nanotube reinforced hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Physica B 2006, 385–386, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, S.; Bahadur, K.C.R.; Dharmaraj, N.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, H.Y. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite using carbon nanotubes as a nano-matrix. Scripta Mater. 2006, 54, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautaray, D.; Mandal, S.; Sastry, M. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite crystals using amino acid-capped gold nanoparticles as a scaffold. Langmuir 2005, 21, 5185–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; de Groot, K. Development of biomimetic nano-hydroxyapatite/poly(hexamethylene adipamide) composites. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 4787–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, Y. Tissue engineering scaffold material of nano-apatite crystals and polyamide composite. Eur. Polym. J. 2004, 40, 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Memoto, R.; Nakamura, S.; Isobe, T.; Senna, M. Direct synthesis of hydroxyapatite-silk fibroin nano-composite sol via a mechano-chemical route. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 2001, 21, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Ashizuka, M.; Ishida, E. Bioactivity and mechanical properties of cellulose/carbonate hydroxyapatite composites prepared in situ through mechanochemical reaction. J. Biomater. Appl. 2006, 21, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, M.; Shiokawa, K.; Morigaki, K.; Tatsu, Y.; Nakahara, Y. Calcium phosphate composite materials including inorganic powders, BSA or duplex DNA prepared by W/O/W interfacial reaction method. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, F.; Miyajima, T.; Yokogawa, Y. A method to fabricate hydroxyapatite/poly(lactic acid) microspheres intended for biomedical application. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russias, J.; Saiz, E.; Nalla, R.K.; Tomsia, A.P. Microspheres as building blocks for hydroxyapatite/polylactide biodegradable composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 5127–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.M.; Cushnie, E.K.; Kelleher, J.K.; Laurencin, C.T. In situ synthesized ceramic-polymer composites for bone tissue engineering: bioactivity and degradation studies. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 4183–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Okada, M.; Maeda, H.; Fujii, S.; Furuzono, T. Hydroxyapatite/biodegradable poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) composite microparticles as injectable scaffolds by a Pickering emulsion route. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zou, S.; Chen, W.; Tong, Z.; Wang, C. Mineralization and drug release of hydroxyapatite/poly(L-lactic acid) nanocomposite scaffolds prepared by Pickering emulsion templating. Colloids Surf. B 2014, 122, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.E. Hydroxyapatite and gelatin composite foams processed via novel freeze-drying and crosslinking for use as temporary hard tissue scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 72A, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohandes, F.; Salavati-Niasari, M. Freeze-drying synthesis, characterization and in vitro bioactivity of chitosan/graphene oxide/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 25993–26001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Das, G.; Sharma, B.K.; Roy, R.P.; Pramanick, A.K.; Nayar, S. Poly(vinyl alcohol)-hydroxyapatite biomimetic scaffold for tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2007, 27, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, A.; Yamane, S.; Akiyoshi, K. Nanogel-templated mineralization: polymer-calcium phosphate hybrid nanomaterials. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickelbick, G. Concepts for the incorporation of inorganic building blocks into organic polymers on a nanoscale. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; de Wijn, J.R.; van Blitterswijk, C.A. Nanoapatite/polymer composites: mechanical and physicochemical characteristics. Biomaterials 1997, 18, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uskokovic, P.S.; Tang, C.Y.; Tsui, C.P.; Ignjatovic, N.; Uskokovic, D.P. Micromechanical properties of a hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide biocomposite using nanoindentation and modulus mapping. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, M.; Kagawa, T. Improvement of fracture energy of HA/PLLA biocomposite material due to press processing. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.M.; Seo, J.; Zhang, R.Y.; Ma, P.X. Suppression of apoptosis by enhanced protein adsorption on polymer/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2622–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baji, A.; Wong, S.C.; Srivatsan, T.S.; Njus, G.O.; Mathur, G. Processing methodologies for polycaprolactone-hydroxyapatite composites: A review. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2006, 21, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Davies, J.E. Preparation and characterization of a highly macroporous biodegradable composite tissue engineering scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2004, 71, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Zhou, H.; Lee, J. Various preparation methods of highly porous hydroxyapatite/polymer nanoscale biocomposites for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3813–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Negi, Y.S.; Choudhary, V.; Bhardwaj, N.K. Microstructural and mechanical properties of porous biocomposite scaffolds based on polyvinyl alcohol, nano-hydroxyapatite and cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose 2015, 21, 3409–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.R.; Ren, J.; Gu, S.Y. Preparation and characterization of porous PDLLA/HA composite foams by supercritical carbon dioxide technology. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2007, 81, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Zhao, P.; Ren, T.; Gu, S.; Pan, K. Poly (D,L-lactide)/nano-hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and biocompatibility evaluation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yue, C.Y.; Chua, B. Production and evaluation of hydroxyapatite reinforced polysulfone for tissue replacement. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2001, 12, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlopek, J.; Rosol, P.; Morawska-Chochol, A. Durability of polymer-ceramics composite implants determined in creep tests. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.; Wilson, C.; Mecholsky, J. Processing and mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite-polysulfone laminated composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 34, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.; Liao, H.; Zhang, L. Preparation and in vivo investigation of artificial cornea made of nano-hydroxyapatite/poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007, 18, 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xiong, G. Porous nano-hydroxyapatite/poly(vinyl alcohol) composite hydrogel as artificial cornea fringe: characterization and evaluation in vitro. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Edn. 2008, 19, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayar, S.; Pramanick, A.K.; Sharma, B.K.; Das, G.; Kumar, B.R.; Sinha, A. Biomimetically synthesized polymer-hydroxyapatite sheet like nano-composite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursamar, S.A.; Orang, F.; Bonakdar, S.; Savar, M.K. Preparation and characterisation of poly vinyl alcohol/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite via in situ synthesis: a potential material as bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Int. J. Nanomanuf. 2010, 5, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, A.; Nayar, S.; Thatoi, H.N. Microwave irradiation enhances kinetics of the biomimetic process of hydroxyapatite nanocomposites. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2010, 5, 024001:1–024001:5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramanik, N.; Biswas, S.K.; Pramanik, P. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite/poly(vinyl alcohol phosphate) nanocomposite biomaterials. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2008, 5, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, A.; Boanini, E.; Gazzano, M.; Rubini, K. Structural and morphological modifications of hydroxyapatite-polyaspartate composite crystals induced by heat treatment. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2005, 40, 1094–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, E.; Bigi, A.; Falini, G.; Panzavolta, S.; Roveri, N. Hydroxyapatite polyacrylic acid nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. 1999, 9, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.J.; Yang, J.; Kodali, P.; Koh, J.; Ameer, G.A. A citric acid-based hydroxyapatite composite for orthopedic implants. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 5845–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greish, Y.E.; Brown, P.W. Chemically formed HAp-Ca poly(vinyl phosphonate) composites. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greish, Y.E.; Brown, P.W. Preparation and characterization of calcium phosphate-poly(vinyl phosphonic acid) composites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2001, 12, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greish, Y.E.; Brown, P.W. Formation and properties of hydroxyapatite-calcium poly(vinyl phosphonate) composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 85, 1738–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailaja, G.S.; Velayudhan, S.; Sunny, M.C.; Sreenivasan, K.; Varma, H.K.; Ramesh, P. Hydroxyapatite filled chitosan-polyacrylic acid polyelectrolyte complexes. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 3653–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piticescu, R.M.; Chitanu, G.C.; Albulescu, M.; Giurginca, M.; Popescu, M.L.; Łojkowski, W. Hybrid HAp-maleic anhydride copolymer nanocomposites obtained by in-situ functionalisation. Solid State Phenom. 2005, 106, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Saiz, E.; Bertozzi, C.R. A new approach to mineralization of biocompatible hydrogel scaffolds: an efficient process toward 3-dimensional bonelike composites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutikov, A.B.; Song, J. An amphiphilic degradable polymer/hydroxyapatite composite with enhanced handling characteristics promotes osteogenic gene expression in bone marrow stromal cells. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8354–8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Bakar, M.S.; Cheng, M.H.W.; Tang, S.M.; Yu, S.C.; Liao, K.; Tan, C.T.; Khor, K.A.; Cheang, P. Tensile properties, tension-tension fatigue and biological response of polyetheretherketone-hydroxyapatite composites for load-bearing orthopedic implants. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, M.S.; Cheang, P.; Khor, K.A. Mechanical properties of injection molded hydroxyapatite-polyetheretherketone biocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, M.S.; Cheang, P.; Khor, K.A. Tensile properties and microstructural analysis of spheroidized hydroxyapatite-poly(etheretherketone) biocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 345, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.P.; Tsui, C.P.; Tang, C.Y. Modeling of the mechanical behavior of HA/PEEK biocomposite under quasi-static tensile load. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 382, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Weng, L.; Song, S.; Sun, Q. Mechanical properties and microstructure of polyetheretherketone-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite materials. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 2201–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yeung, C.Y.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Tjong, S.C. Sintered hydroxyapatite/polyetheretherketone nanocomposites: Mechanical behavior and biocompatibility. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2012, 14, B155–B165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, S.; Wu, X.; Liang, S.; Mu, Z.; Wei, J.; Deng, F.; Deng, Y.; Wei, S. Polyetheretherketone/nano-fluorohydroxyapatite composite with antimicrobial activity and osseointegration properties. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 6758–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.H.; Tang, C.Y.; Hu, H.C.; Zhou, X.P. Improved mechanical properties of HIPS/hydroxyapatite composites by surface modification of hydroxyapatite via in situ polymerization of styrene. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 1141–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, G.; Xia, Z.; Jiang, J.; Jing, B.; Zhang, X. Fabrication and characterization of nanocomposites with high-impact polystyrene and hydroxyapatite with well-defined polystyrene via ATRP. J. Reinf. Plast. Comp. 2011, 30, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petricca, S.E.; Marra, K.G.; Kumta, P.N. Chemical synthesis of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/hydroxyapatite composites for orthopaedic applications. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.S.; Ahn, K.M.; Park, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, C.Y.; Kim, B.S. A poly(lactide-co-glycolide)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffold with enhanced osteoconductivity. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 80, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.; Miyazaki, T.; Lopes, M.; Ohtsuki, C.; Santos, J. Bonelike®/PLGA hybrid materials for bone regeneration: Preparation route and physicochemical characterization. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboudzadeh, N.; Imani, M.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Khavandi, A.; Javadpour, J.; Shafieyan, Y.; Farokhi, M. Fabrication and characterization of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide)/ hydroxyapatite nanocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2010, 94, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Lawrence, J.G.; Bhaduri, S.B. Fabrication aspects of PLA-CaP/PLGA-CaP composites for orthopedic applications: a review. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 1999–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, J.W.M.; Ma, J.; Plachokova, A.S.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Bohner, M.; Pan, J.; Meijer, G.J.; Jansen, J.A.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P. The in vivo performance of CaP/PLGA composites with varied PLGA microsphere sizes and inorganic compositions. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7518–7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L.H.; Naguib, H.E. Characterizing the viscoelastic behaviour of poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid)–hydroxyapatite foams. J. Cell. Plast. 2013, 49, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeoka, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Sugiyama, N.; Yoshizawa-Fujita, M.; Aizawa, M.; Rikukawa, M. In situ preparation of poly(l-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid)/hydroxyapatite composites as artificial bone materials. Polym. J. 2015, 47, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, P.D.; Venugopal, G.; Milbrandt, T.A.; Hilt, J.Z.; Puleo, D.A. Hydroxyapatite-reinforced in situ forming PLGA systems for intraosseous injection. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 2365–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, K.A.; Schmitz, J.P.; Agrawal, C.M. The effects of porosity on in vitro degradation of polylactic acid- polyglycolic acid implants used in repair of articular cartilage. Tissue Eng. 1998, 4, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, C.C.P.M.; Klein, C.P.A.T.; de Blieck-Hogervorst, J.M.A.; Wolke, J.G.C.; de Wijin, J.R.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; de Groot, K. Evaluation of hydroxylapatite poly(L-lactide) composites: physico-chemical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 1993, 4, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, C.M.; Athanasiou, K.A. Technique to control pH in vicinity of biodegrading PLA-PGA implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Appl. Biomater. 1997, 38, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chang, J. pH-compensation effect of bioactive inorganic fillers on the degradation of PLGA. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 2226–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.J.; Miller, S.T.; Zhu, G.; Yasko, A.W.; Mikos, A.G. In vivo degradation of a poly(propylene fumarate)/β-tricalcium phosphate injectable composite scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, M.; Watanabe, M.; Imai, Y. Effect of blending calcium compounds on hydrolitic degradation of poly(D,L-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid). Biomaterials 2002, 23, 2479–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhart, W.; Peters, F.; Lehmann, W.; Schwarz, K.; Schilling, A.; Amling, M.; Rueger, J.M.; Epple, M. Biologically and chemically optimized composites of carbonated apatite and polyglycolide as bone substitution materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 54, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, C.; Epple, M. Carbonated apatites can be used as pH-stabilizing filler for biodegradable polyesters. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, C.; Rasche, C.; Wehmöller, M.; Beckmann, F.; Eufinger, H.; Epple, M.; Weihe, S. Geometrically structured implants for cranial reconstruction made of biodegradable polyesters and calcium phosphate/calcium carbonate. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikinami, Y.; Okuno, M. Bioresorbable devices made of forged composites of hydroxyapatite (HA) particles and poly L-lactide (PLLA). Part II: Practical properties of miniscrews and miniplates. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3197–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russias, J.; Saiz, E.; Nalla, R.K.; Gryn, K.; Ritchie, R.O.; Tomsia, A.P. Fabrication and mechanical properties of PLA/HA composites: A study of in vitro degradation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2006, 26, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, H.; Iwata, M.; Ichinohe, T.; Amimoto, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Kannno, N.; Ochi, H.; Fujita, Y.; Harada, Y.; Tagawa, M.; et al. Hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide acid screws have better biocompatibility and femoral burr hole closure than does poly-L-lactide acid alone. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 28, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Lee, H.H.; Knowles, J.C. Electrospinning biomedical nanocomposite fibers of hydroxyapaite/poly(lactic acid) for bone regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 79, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, K.A.; Rodríguez-Lorenzo, L.M. Biodegradable composite scaffolds with an interconnected spherical network for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4955–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Z. Fabrication and characterization of electrospun PLGA/MWNTs/hydroxyapatite biocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2010, 25, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durucan, C.; Brown, P.W. Low temperature formation of calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite-PLA/PLGA composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durucan, C.; Brown, P.W. Calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite-PLGA composites: mechanical and microstructural investigation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 51, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durucan, C.; Brown, P.W. Biodegradable hydroxyapatite-polymer composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2001, 3, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazhat, S.N.; Kellomäki, M.; Törmälä, P.; Tanner, K.E.; Bonfield, W. Dynamic mechanical characterization of biodegradable composites of hydroxyapatite and polylactides. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 58, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]