Multi-Layered Roles of Religion among Refugees Arriving in Austria around 2015

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Religion and Displaced Persons Arriving in Austria in Recent Years

3. Method

4. Results

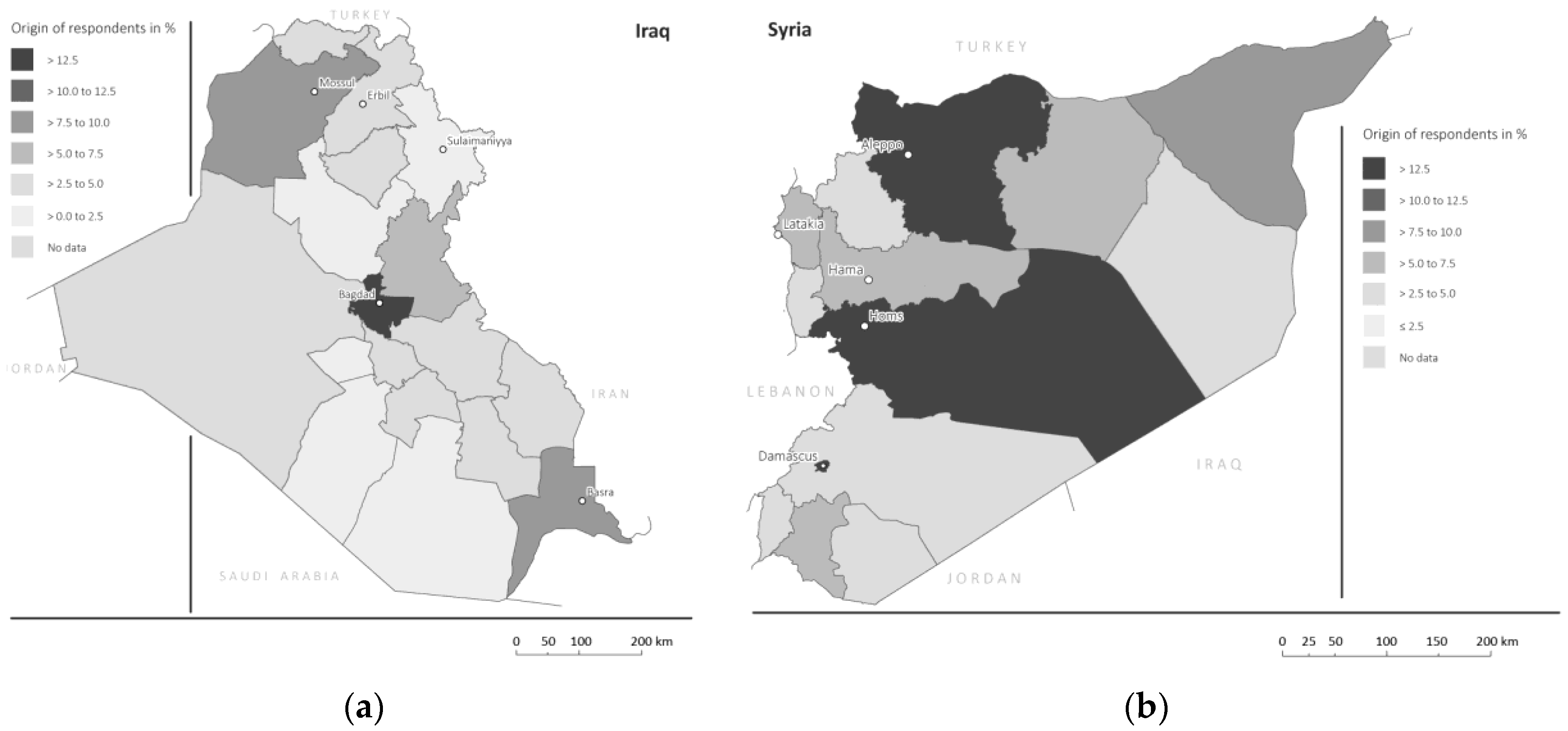

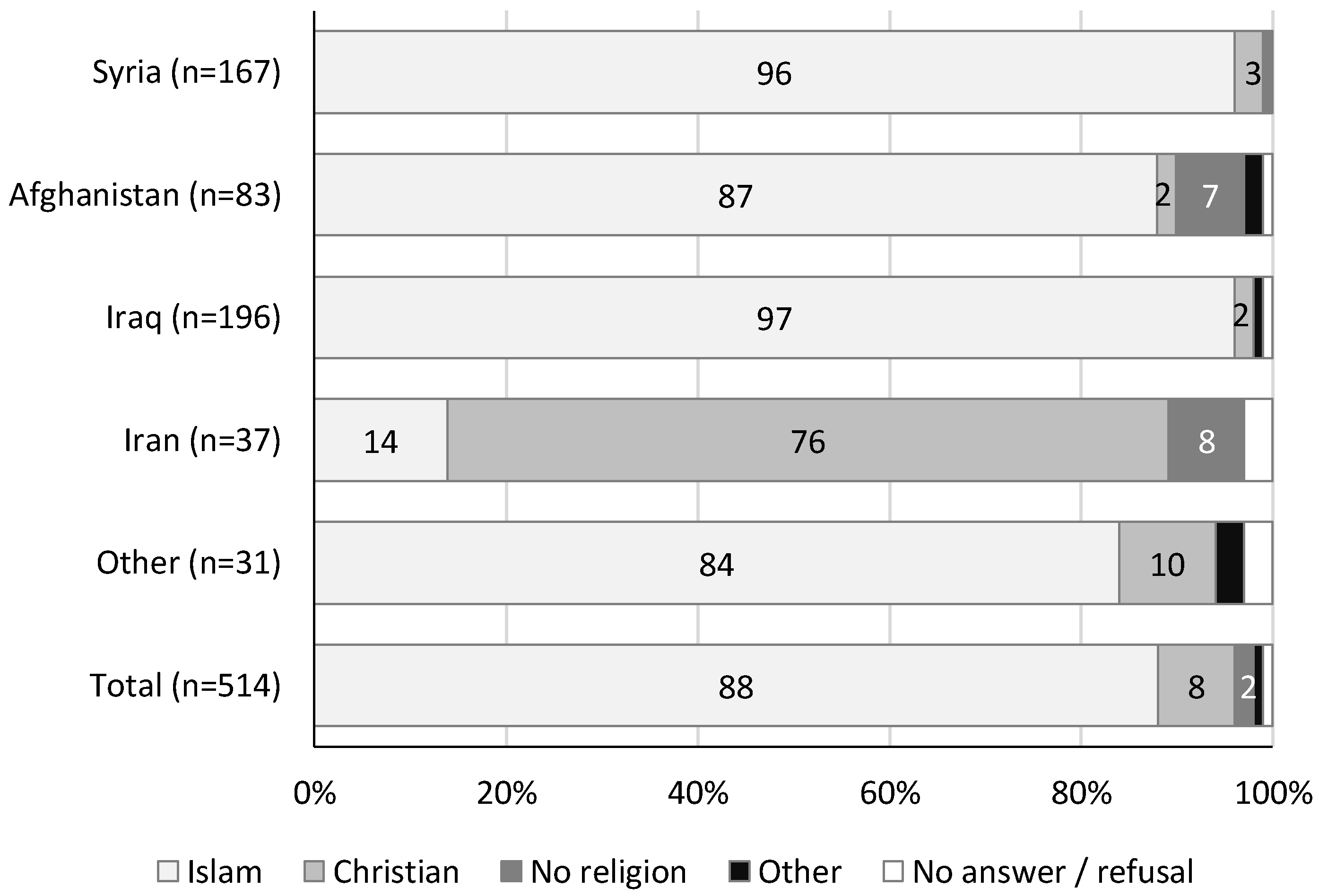

4.1. Religious Affiliation and Religiosity

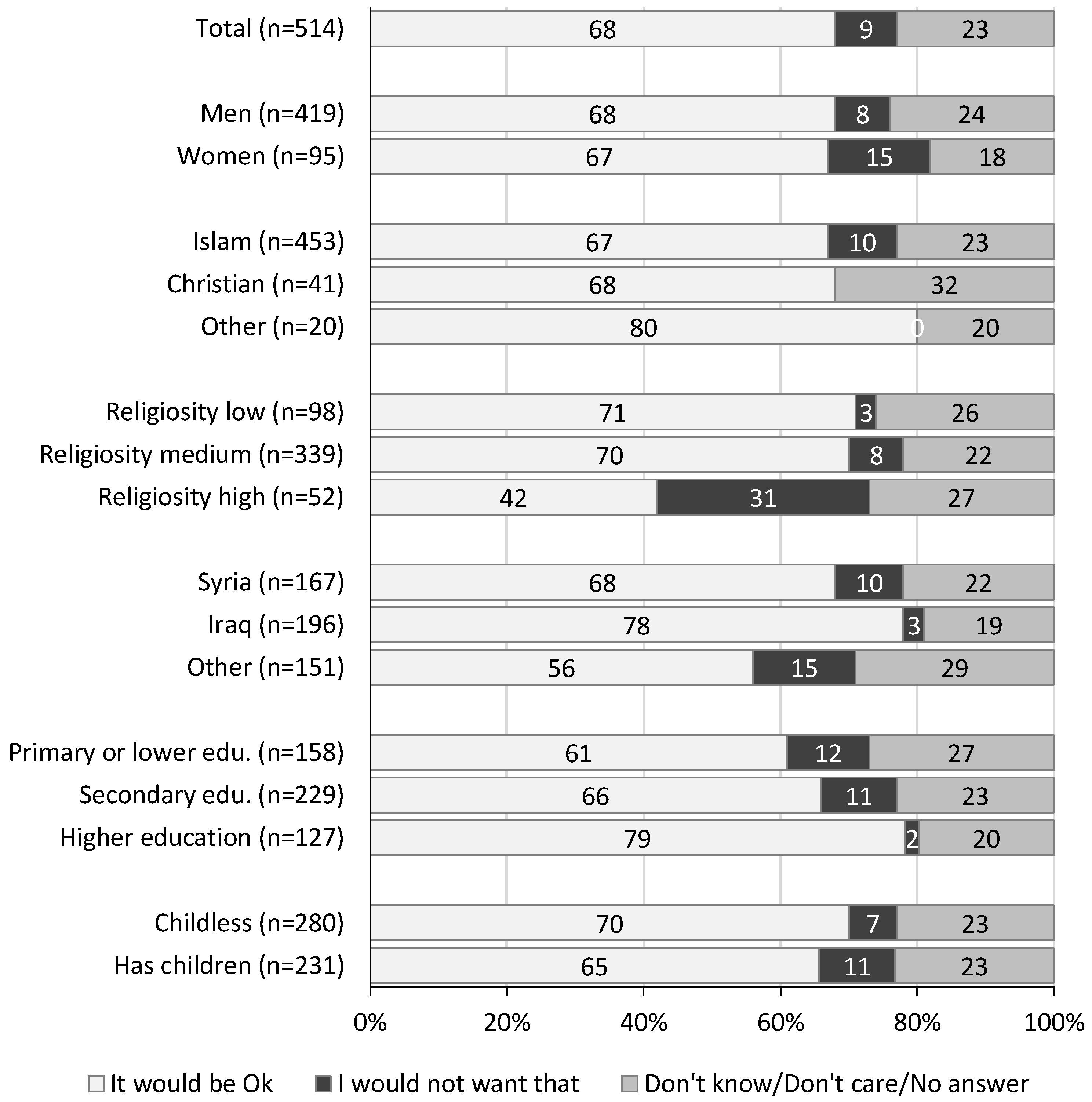

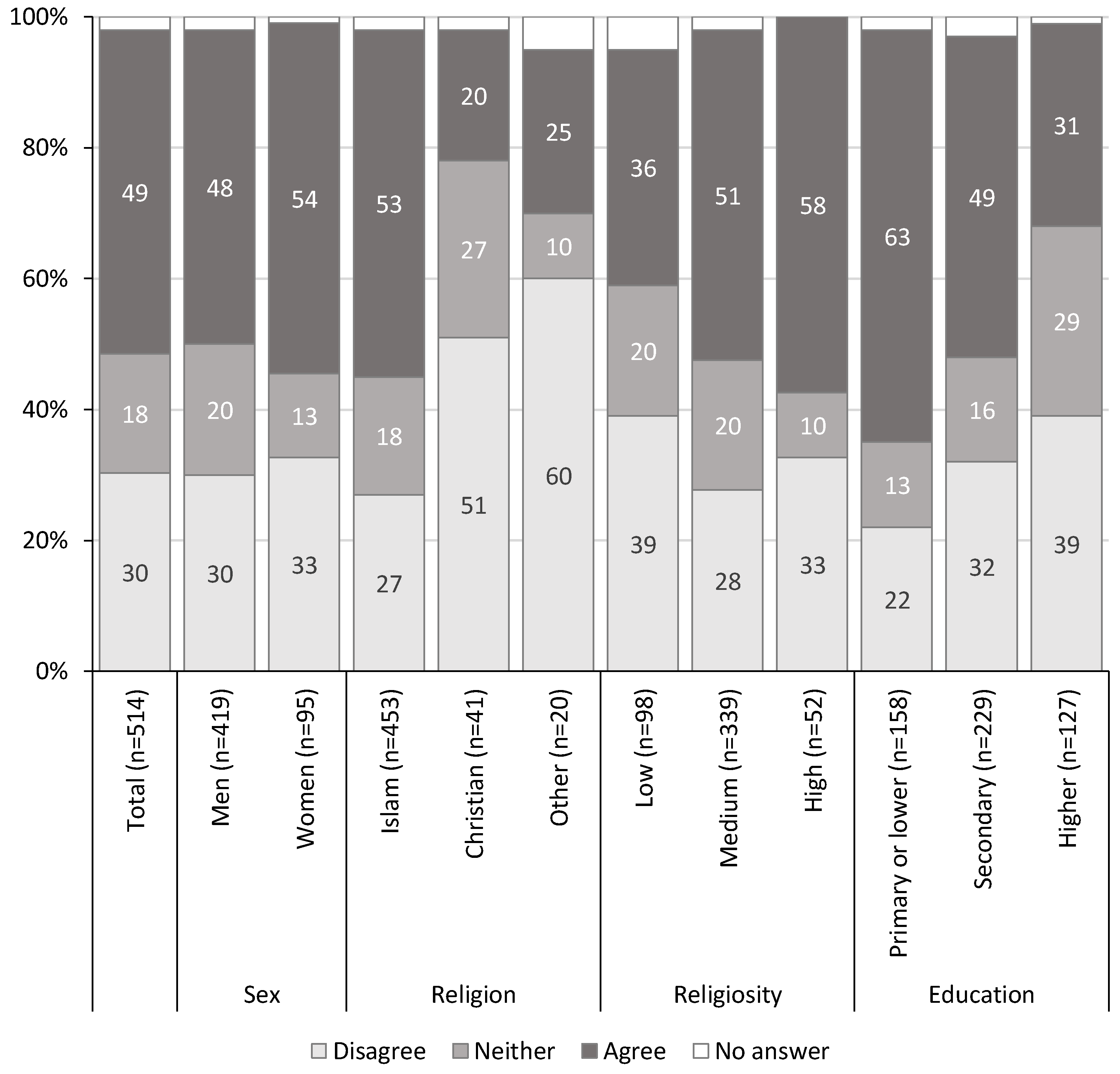

4.2. Secularization

4.3. Social Attitudes and Religiosity

4.4. Religion and First Steps in the Host Society

4.5. Collective and Individual Religious Identity

4.6. The Role of Religion and Religious Communities in the Wake of the European ‘Refugee Crisis’

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aida. 2016. The Length of Asylum Procedures in Europe. Aida (Asylum Information Database). Brussels: European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE). [Google Scholar]

- Aleksynska, Mariya, and Barry R. Chiswick. 2011. Religiosity and Migration: Travel into One’s Self versus Travel across Cultures. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5724. Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). [Google Scholar]

- Bawer, Bruce. 2007. While Europe Slept: How Radical Islam Is Destroying the West From Within. New York: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Berghammer, Caroline, Ulrike Zartler, and Desiree Krivanek. 2017. Looking beyond the church tax: Families and the disaffiliation of Austrian Roman Catholics. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 514–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Mike. 2015. Welcome to the ‘Rechtsrutsch’: The Far Right Is Quietly Making Massive Gains in Europe. Business Insider UK. Available online: http://uk.businessinsider.com/the-far-right-is-quietly-making-massive-gains-in-europe-2015-10?IR=T (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- Buber-Ennser, Isabella, Judith Kohlenberger, Bernhard Rengs, Zakarya Al Zalak, Anne Goujon, Erich Striessnig, Michaela Potančoková, Richard Gisser, Maria Rita Testa, and Wolfgang Lutz. 2016. Human capital, values, and attitudes of persons seeking refuge in Austria in 2015. PLoS ONE 11: e0163481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, Ted Galen. 2012. Tangled Web: The Syrian civil war and its implications. Mediterranean Quarterly 24: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, Sergio, Steven Blockmans, Daniel Gros, and Elspeth Guild. 2015. The EU’s Response to the Refugee Crisis: Taking Stock and Setting Policy Priorities. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Castles, Stephen, Hein De Haas, and Mark J. Miller. 2013. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 5th ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Commins, David, and David W. Lesch. 2014. Historical Dictionary of Syria, 3rd ed. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, Stephen M. 2013. Integrated threat theory and acceptance of immigrant assimilation: An analysis of Muslim immigration in Western Europe. Communication Monographs 80: 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, Stephen M., and Daniel Cronn-Mills. 2011. Religious Misperceptions: The Case of Muslims and Christians in France and Britain. New York: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culik, Jan. 2015. Anti-immigrant walls and racist tweets: The refugee crisis in central Europe. The Conversation, June 24. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, Sara, and Ilker Ataç. 2017. Demand and deliver: Refugee support organisations in Austria. Social Inclusion 5: 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorais, Louis J. 2007. Faith, hope and identity: Religion and the Vietnamese refugees. Refugee Survey Quarterly 26: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tayeb, Fatima. 2011. European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich, Florentine. 2017. Was die Schließung der Balkanroute bewirkt hat [What the Closure of the Balkan Route Has Caused]. Frankfurter Allgemeine. Available online: http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/was-die-schliessung-der-balkanroute-bewirkt-hat-14915297.html#void (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Fetzer, Joel S., and Christopher Soper. 2005. Muslims and the State in Britain, France, and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foner, Nancy, and Richard Alba. 2008. Immigrant religion in the US and Western Europe: Bridge or barrier to inclusion? International Migration Review 42: 360–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, Reza. 2015. Secularism and Identity: Non-Islamiosity in the Iranian Diaspora. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Goujon, Anne, Sandra Jurasszovich, and Michaela Potančoková. 2017. Religious Denominations in Austria: Baseline Study for 2016—Scenarios until 2046. Öif-Forschungsbericht [Reseach Report]. Vienna: Österreichischer Integrationsfonds [Austrian Integration Fund]. [Google Scholar]

- Goujon, Anne, Vegard Skirbekk, Katrin Fliegenschnee, and Pawel Strzelecki. 2007. New times, old beliefs: Projecting the future size of religions in Austria. In Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 237–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gozdziak, Elzbieta M., and Dianna J. Shandy. 2002. Editorial introduction: Religion and spirituality in forced migration. Journal of Refugee Studies 15: 129–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainmüller, Jens, Dominik Hangartner, and Duncan Lawrence. 2016. When lives are put on hold: Lengthy asylum processes decrease employment among refugees. Science Advances 2: e1600432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hill, Peter C., and Ralph W. Hood. 1999. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ichou, Mathieu. 2016. Accueillir toute la misère du monde? Le trompe-l’oeil d’une vision misérabiliste de l’immigration [Welcoming all the world’s misery? The illusion of a miserabilistic vision of immigration]. In Au-delà de la crise des migrants: décentrer le regard [Beyond the Migrant Crisis: Decentering the Perspective]. Edited by Cris Beauchemin and Mathieu Ichou. Paris: Karthala, pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel C. 1997. Formal education vs. religious belief: Soliciting new evidence with multinomial logit modeling. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 231–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, Pia. 2017. Syrian Identities According to Austrian Aid Workers: Debating Identity/Alterity. Paper presented at the ROR-n Lecture, Vienna, Austria, 27 January. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzberger, Martin. 2018. Erhebung Taufwerbende/evanglelisch getaufte AsylwerberInnen/Asylberechtigte [Survey of Candidates for Baptism/Evangelical Baptism among Asylum Seekers and Refugees]. Vienna: Evangelical Church AC and HC in Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlbacher, Josef. 2017. Steps on the way to social integration. In From Destination to Integration—Afghan, Syrian and Iraqi Refugees in Vienna. Edited by Josef Kohlbacher and Leonardo Schiocchet. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, pp. 167–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlenberger, Judith, Isabella Buber-Ennser, Bernhard Rengs, and Zakarya Al Zalak. 2016. A Social Survey on Asylum Seekers in and around Vienna in Fall 2015: Methodological Approach and Field Observations. VID Working Paper 6/2016. Vienna, Austria: Vienna Institute of Demography. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu, Hill, and Amparo González-Ferrer. 2014. Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities. European Journal of Population 30: 411–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliepaard, Mieke, Mérove Gijsberts, and Marcel Lubbers. 2012. Reaching the limits of secularization? Turkish-and Moroccan-Dutch Muslims in The Netherlands 1998–2006. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 359–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, Astrid. 2017a. Part of the problem or of the solution? The involvement of religious associations in immigrant integration policy. OZP—Austrian Journal of Political Science 46: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, Astrid. 2017b. Who we are is what we believe? Religion and collective identity in Austrian and German immigrant integration policies. Social Inclusion 5: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, Astrid. 2018. How religion came into play: ‘Muslim’ as a category of practice in immigrant integration debates. Religion, State & Society 46. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2012. Muslim integration into Western cultures: Between origins and destinations. Political Studies 60: 228–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PEW. 2012a. The Global Religous Landscape. Washington: PEW Forum on Religion and Public Life. [Google Scholar]

- PEW. 2012b. The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Washington: PEW Forum on Religion and Public Life. [Google Scholar]

- Potančoková, Michaela, and Caroline Berghammer. 2014. Urban faith: Religious change in Vienna and Austria, 1986–2013. In Religion in Austria, Volume 2. Edited by Hans Gerhard Hödl and Lukas Pokorny. Vienna: Praesens Verlag, pp. 217–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schmiedel, Ulrich, and Graeme Smith, eds. 2018. Religion in the European Refugee Crisis. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Patrick, and Vincent Tiberj. 2013. Sécularisation ou regain religieux: La religiosité des immigrés et de leurs descendants. In Trajectoires et origines: Enquête sur la Diversité des Populations en France. Edited by Cris Beauchemin, Christelle Hamel and Patrick Simon. Paris: INED Editions. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. 2015. Diverse, Desperate Migrants Have Divided European Christians. The Economist. Available online: http://www.economist.com/blogs/erasmus/2015/09/migrants-christianity-and-europe (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Trzebiatowska, Marta, and Steve Bruce. 2012. Why Are Women More Religious Than Men? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Enzo, and Roland Weigand. 2016. Identifying Macroeconomic Effects of Refugee Migration to Germany. IAB Discussion Paper 20/2016. Nürnberg, Germany: Institut für Arbeitsmarkt-und Berufsforschung (IAB). [Google Scholar]

- Worbs, Susanne, and Eva Bund. 2016. Qualifikationsstruktur, Arbeitsmarktbeteiligung und Zukunftsorientierungen [Qualification Structure, Labour Market Participation and Orientation towards the Future]. 1/2016 der Kurzanalysen des Forschungszentrums Migration, Integration und Asyl des Bundesamts für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Nürnberg: Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF). [Google Scholar]

- Zulehner, Paul. 2011. Verbuntung. Kirchen im weltanschaulichen Pluralismus. Religion im Leben der Menschen 1970–2010 [Becoming More Colourful. Churches in Ideological Pluralism. Religion in the Life of the People 1970–2010]. Ostfildern: Grünewald. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | E.g., in Syria, president Assad has been alleged to favor the Shia Alawites over other affiliations, particularly the country’s Sunni majority. Persecution of religious minorities (both Islamic and of different traditions) has been particularly rampant in the areas conquered by the Islamic State (ISIS) terrorist organization. Religious identity is thus a sensitive issue for many Syrians, as well as for Iraqis and other refugees arriving from areas where sectarian violence has been virulent. |

| 2 | Proportion of Muslims in the country of origin: 99.7% in Afghanistan, 99% in Iraq, and 92.8% in Syria, 48.8% in Nigeria, and 99% in Somalia (PEW 2012a). |

| 3 | They have officially been granted either asylum status under the Geneva Convention or subsidiary protection or other humanitarian protection. Among them, one in two had Syrian nationality (49%), one in two Afghan (18%). Iraqis and Iranians comprised only a small proportion of positive asylum applications in 2015–2017 (7% and 3% respectively). |

| 4 | “Diverse, desperate migrants have divided European Christians” in The Economist, September 6, 2015 (The Economist 2015). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | As the survey includes also information on spouses and children, in total 1391 individuals were captured in the survey, 972 of them living in Austria at the time of the interview and 419 living abroad (Buber-Ennser et al. 2016). |

| 7 | Most telephone numbers provided at the time of the interview in 2015 were no longer valid. |

| 8 | We refer to https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163481.s004 for the English questionnaire. |

| 9 | The exact wording of the question was: “Apart from the fact of belonging to a religious community or not, how religious do you consider yourself?”. |

| 10 | The Austrian GGS carried out in 2008/09 comprises 5001 men and women aged 18 to 45 years. The survey on “Quality of Life in Vienna” was conducted in 2012/2013 and interviewed 8400 individuals. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Quality of Life in Vienna survey 2012/13. |

| 13 | Mostly of Turkish and Bosnian origin. |

| 14 | However, at the time of the survey, the ISIS did not occupy large parts of Syria and Iraq, and attacks by Muslim fundamentalists in Europe were less frequent compared to 2015. Therefore, Viennese Muslims may not have felt worried at the time of the survey about being mistaken for extremists if they reported being very religious. |

| 15 | 12% were not religious at all, and 11% reported having low levels of religiosity. |

| 16 | Shiah Islam is believed to be closer to Christianity culturally and in the scriptures compared to other Muslim sects. |

| Religiosity | Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refugee population | Low level (1–2) | 24% | 4% | 20% |

| Medium level (3–8) | 67% | 78% | 69% | |

| Very religious (9–10) | 9% | 18% | 11% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Austrian population | Low level 2 (0–2) | 27% | 20% | 23% |

| Medium level (3–8) | 66% | 66% | 66% | |

| Very religious (9–10) | 7% | 14% | 10% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religious groups | 16% | 22% | 17% |

| Sport clubs | 36% | 20% | 34% |

| Other groups | 7% | 7% | 7% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buber-Ennser, I.; Goujon, A.; Kohlenberger, J.; Rengs, B. Multi-Layered Roles of Religion among Refugees Arriving in Austria around 2015. Religions 2018, 9, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9050154

Buber-Ennser I, Goujon A, Kohlenberger J, Rengs B. Multi-Layered Roles of Religion among Refugees Arriving in Austria around 2015. Religions. 2018; 9(5):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9050154

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuber-Ennser, Isabella, Anne Goujon, Judith Kohlenberger, and Bernhard Rengs. 2018. "Multi-Layered Roles of Religion among Refugees Arriving in Austria around 2015" Religions 9, no. 5: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9050154

APA StyleBuber-Ennser, I., Goujon, A., Kohlenberger, J., & Rengs, B. (2018). Multi-Layered Roles of Religion among Refugees Arriving in Austria around 2015. Religions, 9(5), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9050154