1. Introduction

The social work profession and social work education are increasingly recognizing the importance of faith, religion and spirituality in our clients and students. The National Association of Social Work Code of Ethics [

1] and the Council on Social Work Education Accreditation Standards [

2] each include religion as an area of diversity requiring cultural competence for practice. In 2002, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) published a case book which focused specifically on decision cases around spirituality and religion in social work practice. Concurrently, the church, which has historically been a foundational institution for responding to human needs, is increasingly acknowledging the importance of professionally trained social workers for delivering effective and efficient human services [

3].

Religious traditions and congregations characteristically provide social services to meet the needs of humankind. consistent with the Examples of this involvement include Jewish Social and Community Services, Buddhist Global Relief, Islamic Social Services Association, and others.

This article focuses on the ways that Christian congregations contribute to this religion-based commitment to social provision. Ellor, Netting, and Thibault noted that “Jewish and Christian traditions have dominated the processes which have shaped values and guided social welfare policy in the United States” ([

4], p. 15). One distinctive seems to be that social services organizations in faith traditions other than Christianity are more likely to have a secular focus than faith integration ([

4], p. 166). The focus of this paper is on the predominantly Christian affiliated organizations in the United States that sponsor social service work, recognizing that the same principles can apply in other traditions.

The convergence of interest from the profession and from churches/congregations and religiously-affiliated organizations (RAOs) energizes recent attention to the role, impact, and appropriateness of social workers in this area of practice. Garland [

5,

6] wrote about the concept of church social work and social workers in congregations. Northern [

7] followed with a study of social workers in congregational contexts, previously referred to as churches. Both wrote from a Christian congregation contextual experience. Garland and Yancey [

8] document, in their seminal book on congregations as a context for social work practice, the prevalence and the practice of social workers in congregations.

Recognition that social workers are, in fact, practicing in these settings focuses attention on how social work education is preparing professionals for congregationally-related practice. More specifically, it is important for social work educators and practitioners to know how social work internship experiences inform preparation for work with congregations and RAOs. Building on definitions and conceptualization offered by Garland and Yancey [

8], we critically examine the possibilities and issues involved in the design and delivery of congregationally-related internships and report findings and implications from an evaluation of a single congregational and a rotational field model of internship placements in congregations and RAOs.

2. Field Education as Signature Pedagogy

While the CSWE, the accrediting body for social work education programs, identified field education as the signature pedagogy for the profession, Holden, Barker, Rosenberg, Kuppen, and Ferrell [

9] found little evidence in their meta-analysis that field education is uniformly situated at the core of the curriculum. Larrison and Korr [

10] stated that the requirement for a signature pedagogy is that it prepares students to both think like and behave like a member of the profession. That suggests that field placement sites would consistently provide a context for the development of professional competencies and demonstrate a pattern of hiring social work graduates.

The signature pedagogy literature relies heavily on work by Lee Shulman in studying signature pedagogy in five professions: medicine, law, nursing, engineering, and clergy [

10,

11]. Shulman asserted that emotional investment in the field experience, even when it includes anxiety, is necessary to learning. This component is part of what elevates field education to critical importance, at least as significant as classroom education [

11].

Copp [

12] discussed the importance of field education noting that ministerial students are best prepared for reflective practice though internships,

i.e., real life experience. Copp supports the importance of field education in congregations for those students who expect to work in social work roles in the church with some professional identity of minister. Further, some social work programs have added dual degree programs for social work students who specifically prepare for ministry and practice in congregational settings or RAOs as an extension of their faith.

Congregations can provide social workers with competency-friendly contexts regardless of the student’s particular career interests. As is the case with other placements, interns participate in an orientation to the mission of the organization and preparation for the social work role and responsibilities in the congregational context. The distinctive of internship preparation in these religiously affiliated settings is that it is specific to the content of the congregation’s unique mission and the social work roles in interaction with minister and clergy roles.

3. Defining and Conceptualizing Social Work with Congregations and RAOs

For the purposes of this article, we define a congregation as a religious community assembled, in most cases Christian, for the purpose of worship of a deity or deities, study and enactment of religiously prescribed beliefs and practices, and usually having a physical location. The term, church, is also used interchangeably with congregation. Jeavons and Netting [

8] view the congregation as a generally more inclusive concept while church refers in this article exclusively to Christian-based religious communities. Because the preponderance of research on social work and religious communities is based on Christian institutions, we utilize, from time to time, church in references to Christian congregations. We recognize that these concepts are applicable to field internships in other religiously affiliated entities like Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim, and other affiliated agencies. Further, there is no implied requirement that the student be of the same religious persuasion of the agency in order for social services to be delivered effectively.

Garland and Yancey defined RAOs as those which “identify with a congregation, multiple congregations, a religious order, denomination or some other religious organization” ([

13], p. 15). Some are affiliated historically and others “pursue a mission and espouse values described in religious language” ([

13], p. 15). Prior to this, in 2011, the Ninth Circuit Court addressed Title XXX issues by defining religious organizations this way:

Although the court did not formulate any clear test, the two tests can be combined to determine what organizational requirements must be met. First, the hypothetical corporation must be organized for a religious purpose, and the purpose must be set forth in the articles of incorporation. Second, the actions of the corporation must be consistent with the religious purpose. Third, the corporation must hold itself out to the public to be a religious organization. Fourth, the corporation must be non-profit. Fifth, the corporation must offer products for free, or for a nominal amount [

14].

Garland and Yancey [

8] defined congregational social work as providing professional practice “in and through a religious congregation, whether the employer is the congregation itself or a social service or denominational agency working in collaboration with congregations” ([

8], p. 1).

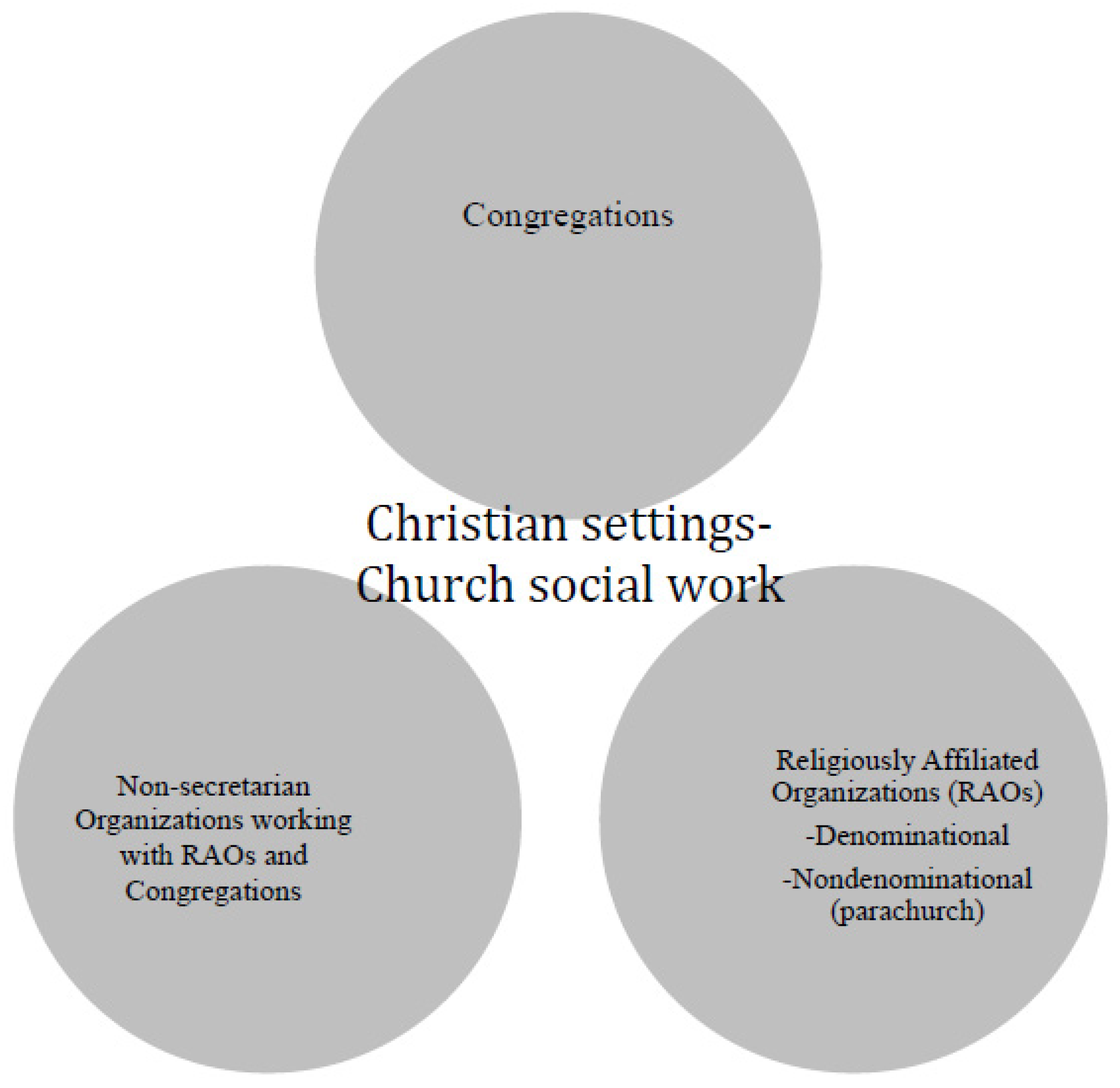

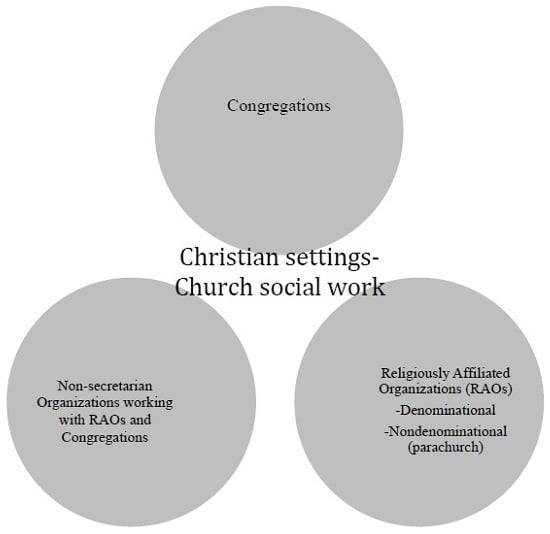

Figure 1 illustrates the dimensions and variations that encompass the conceptualization of congregational social work.

As is shown in

Figure 1, this arena of practice includes relating to, with, and for congregations, RAOs, and non-sectarian settings. Importantly, these authors suggested that while social workers are able to work in congregations as the specific field of practice, they also are an important part of the web of relationships that is possible with other congregations, RAOs, and non-sectarian agencies, including government ([

8], p. 17).

4. Historic and Current Trends

Much of the literature specific to RAOs and congregational social work is fairly recent. The roots of the profession include significant contributions by persons of faith, congregations and RAOs, all of which have been consistent providers of community services throughout social service history [

3]. It should be noted that the involvement of the church as a context for social work practice was historically enacted through affiliations with denominational and adjudicatory agencies and associations. Garland [

6] about the historical roots of social services in the church and observed that many, in some cases a third of referrals by workers in social service organizations, were made to the church, specifically for food, clothing, and financial assistance. They recommended that social workers both practice in the church and practice in collaboration with the church to meet the needs of the poor and oppressed. As early as 1930, Johnson detailed the “social work of the churches” in a National Federation of Churches report [

15]. This report included the contributions of congregations by type of social service provision, with a strong emphasis on advocacy and social justice.

Beginning with the 1900s, the focus of the profession turned significantly to the scientific method and positivist models, even as the church continued to provide a safety net of social services, often for congregants and sometimes for communities as well [

16] These authors recommended that the profession reconnect with those religious roots of the profession and find ways to partner with congregations.

In 1942, the National Conference of Catholic Charities began publishing a series of monographs entitled Certain Aspects of Case Work Practice in Catholic Social Work.

These monographs were focused on casework practice in Catholic social service agencies. This series was followed by the first publications in the early 1960s of congregational social work articles which were located in professional social work literature. The term “parish social work” was used by Martin Ferm [

17] as a description of the context of practice for a social worker who is on the staff of a Lutheran congregation. Alice Taggart [

18] reflected on her work as a “parish assistant” in a Unitarian congregation in New York.

Moore and Collins [

19] wrote specifically about the importance of social work services in African-American churches and recommended that field placements in these settings would provide students with experience with diversity. Larson and Robertson [

20] observed the experiences of three baccalaureate social work students placed in faith-based agencies and concluded that programs need to better prepare students for addressing issues of faith and practice. Child welfare services, for example, find a rich history in the work of the church through the development of orphanages, children’s homes, and homes for “unwed mothers.” Scales [

21], for example, described the development of Buckner Orphan’s Home in Dallas, Texas, a ministry that now has international outreach and services.

Garland and Yancey completed in-depth interviews with 51 social workers in churches and congregations and concluded that their practice in this setting can best be described as community ministry including activities like “benevolence, emergency assistance, and tutoring activities” ([

8], p. 5). In some cases, community ministry involved offering the benevolence and caring ministries historically offered to congregants and to the larger community and neighborhoods. On the other hand, the interview findings from other respondents revealed that community ministry included supporting RAOs, which were sometimes also the ministries of specific Christian denominations.

While there is not much written about congregational social work, there is even less written about field placements in churches or congregational settings. Settings, or contexts of practice, are described, but there is a void in finding discussions about field placements in congregational settings. One exception is the study by Poole, Rife, Pearson, Moore, Reaves, and Moore [

22] in which he reported on the Congregational Social Work Education Initiative’s (CSWEI) work of seven years in developing a model of interdisciplinary teams including social work students under the supervision of congregational nurses and licensed social workers. The authors also acknowledged the importance of field placement opportunities including a rotational model in religiously-affiliated organizations and congregations.

The progressive and sustained attention to the role of social work practice in religious settings attests to the growth of investment in this area [

23]. This trend continues today as does the role of religious denominations in providing areas including crisis and disaster response, hospitals and medical care, and family and child services. As we documented, current literature does not emphasize social work or social work field placements in congregations. The relevance of this topic is both about the need for professionals who know how to competently engage the church as a viable contributor to a community’s web of services as well as the need for social workers who practice in congregations and religiously affiliated agencies. Further, social workers in RAOs or agencies need to be prepared to consult with congregations and other RAOS and secular non-profits. These settings provide an important context for preparation of social work students.

5. The Use of RAOs in Field Education in CSWE Programs

Organizations that participate in social work education by providing internships are also called field placements and are by definition “the settings in which students complete the required agency-based experience for their social work programs” ([

24], p. xvii). Berg-Weger and Birkenmaier describe a diversity of settings in which social work falls on a continuum from primary to secondary service delivery providers. The field education literature, however, does not include a discussion of congregations as field practicum sites. Keith-Lucas [

25] wrote about church children’s homes in a series of essays that addressed the influence and support of the church. The author did not, however, address social work field education at that time. The tendency has been to identify large-system RAOs like Lutheran Social Services and Catholic Charities as the main context for social work involvement in religious settings.

Of the approximately 771 accredited social work programs in the United States, there are hundreds of religiously-affiliated programs. Further, fully a fourth of accredited baccalaureate social work programs in the United States are in faith affiliated accredited social work programs. Social work students who identify as Christians or “persons of faith” are not all at faith-affiliated schools. Significantly, many students in state, public social work education programs report faith affiliations and religious values that impact their social work practice. These students struggle with how to integrate their religious faith and may well work after graduation in faith-based organizations with no help or preparation for the integration of faith and practice from their educational programs. Since some students in both public and private programs are interested in social work practice in faith-based organizations, it makes sense to prepare them for the work in field internships in these settings. The recognition by professional social work educators of congregations as contexts for social work practice is essential to this preparation.

A search of web sites with CSWE accredited BSW and MSW programs and their field education programs and sites (2007) revealed that of the 675 schools listed, 154 (23%) schools posted field placement options on their websites; it was difficult to ascertain which were faith based and which were not. Forty-eight public programs with field placements on websites included an average of 98 field placement sites with an average of seven faith based organizations. Faith-based organizations in public social work field education are significantly underutilized. The same is true of religiously affiliated schools with field education on their websites. Most include no faith-based organizations. Of the 32 websites examined, there was an average of 48 field placement sites per program with an average of only four faith- based organizations per program. The same trend was noted in MSW field education. There are both strengths and challenges to consider in using congregations and RAOs for social work field placements and social work employment. While it is true that many social work programs do not list their field placement sites on their websites making this a limited picture of field education, this glimpse suggests that congregational and religiously affiliated placements may be under-utilized.

In the field education program of the authors, 120 RAOs have served as approved field education sites in the years 1990–2016. Of those, 15 were in other states; five were in international sites. Additionally, the program approved 43 congregations as field sites for internships; seven in other states. Those congregations included Baptist, Methodist, Episcopalian, AME, Presbyterian, non-denominational, and Salvation Army sites [

26].

6. Strengths and Challenges of Congregational and RAO Field Placements

As is true with all educational innovations, the strengths and challenges of placing students in congregations and RAOs need to be examined carefully for the unique field experiences that are possible in both.

6.1. Strengths

Congregations and RAOs are historically the settings of many social services in the United States including services like children’s homes, hospitals and medical care, and community services for the homeless and the poor. A number of RAOs provide social services across the United States; examples include Lutheran Social Services and Catholic Charities and smaller organizations like children’s homes affiliated with Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist denominations. Churches in a number of denominations provide counseling and therapy centers, food and shelter for persons who are homeless, and a response in times of crisis and disaster. Usually, many of these services are delivered by ministry staff and volunteers who do not have the benefit of social work knowledge, values, and skills [

3]. There is tremendous opportunity and need for fully prepared social workers who know how to competently work with congregations and even function as employees of congregations and RAOs. Congregations of all sizes are located in communities of all sizes in rural, suburban, and urban contexts. Social work field internships in these sites provide the congregation or agency the opportunity to understand and see in action the social work role. In the authors’ social work education program, congregational internship placements have led to the development of long-term compensated social work positions within these host settings. In cases like this, the congregation or RAO benefits from social work knowledge and skills. Where the integration of faith and practice is an accepted part of the work, the social work intern and/or employee benefit from the opportunity to work in this setting. This opportunity for the ethical integration of faith and practice is a value that adds credence to social work practice in a (w)holistic way.

6.2. Challenges

The social work profession historically adheres to a set of professional values, including self-determination, for example, for clients. This value is juxtaposed against the concern that congregations and RAOs are committed to proselytizing and religious conversion. This value dilemma has resulted in concern that the social worker in a faith-based setting will use the position of influence in the helping process to impose the value of faith on clients. For a period of social work education and practice history, there was a prescriptive separation of the social worker’s faith and practice. Social work students were taught that their faith experience and beliefs and those of the client were off limits in the helping process. Current research, however, helps us see a different perspective from the lens of social work clients. Oxhandler, Parrish, Torres, and Achenbaum [

27] found that many clients would like for social workers to address clients’ spiritual and religious values as a part of social work practice.

The clear separation between social work education and religious beliefs and practices remains a key tenet in many social work programs, although the recent emphasis on spirituality and the inclusion of religion as part of culture has begun to have on-going dialogue and new opportunities for social work educators to address this through competency based educational experiences. This historic segregation of spirituality and preparation for practice presents several challenges in creating and sustaining congregational and RAO internships. One challenge is that more experienced social workers may well not have been professionally prepared to address the ethical integration of religious faith and practice in congregations and RAOs. Consequently, enlisting qualified and willing supervisors for internships can be problematic. Second, these more non-traditional settings are often not accustomed to the role of social work and the contributions the profession can make to the mission of their organizations. The challenge for schools of social work is to address the concern around imposition of values and role definition with the opportunity that social work knowledge and skills offers in settings that routinely provide resources, counseling, and community development services. Programs can address this challenge with rigorous attention to providing social work supervision that clarifies role and purpose. A third challenge is that many students are in programs where they may not be prepared for the ethical integration of religious faith and professional practice. The opportunity and challenge is to conceptualize the integration of faith and practice through three lenses which we discuss here: (1) the faith of the client; (2) the faith of the social worker; and (3) the affiliation of the organizational context. The work of Garland and Yancey [

8], Sherwood [

28] and Chamiec-Case [

29] provides literature to begin to address this challenge.

7. Conceptualizing the Integration of Religious Faith and Practice

The authors report on findings from congregational and RAO internship placements based on the three-component model for the ethical integration of religious faith and practice that includes the essential components. Organizing instruction and internship learning was adopted by respecting and valuing the faith lens of the client; the faith lens of the social worker; and the organizational context.

8. Faith Lens of the Client

Understanding the client’s holistic experience includes assessment of relevant emotional, cognitive, physical, social, and spiritual variables. This includes religious faith for some as support and strength in times of crisis; for others, this is experienced as a challenge including the experience of marginalization in the church when dealing with social issues. Understanding these dynamics is important for social workers to help clients create their plans for change.

9. Faith Lens of the Social Worker

Self-awareness is a fundamental principle of good social work practice. All social workers have a world view that impacts how they make meaning out of the challenges they face and the challenges clients face. The social worker’s religious faith matters because it provides part of that lens through which the social worker sees the world and in some cases provides the motivation for the work. For many social workers, religious faith is a highly regarded value that informs their social work practice. This value should be respected by social work professionals as much as the values of dignity and worth, self-determination, and social justice are in professional social work. It is not unethical for the social worker to experience or respond to a call or sense of vocation to social work. It would be unethical for the social worker not to be self-aware that that call is about the social worker, not about the client. It would be unethical to impose the social worker’s call or beliefs on the client.

10. Organizational Context

Organizational context is shaped by the mission, funding, and affiliations of the organization. Policies operationalize the mission of the agency or congregation. Additionally, the application of the law around discrimination impacts agencies. The separation of church and state in state or federally funded agencies includes both the protection against the state imposing or prescribing religion and against the state prohibiting or proscribing religion. While the mission of RAOs and congregations may be to share their own religious faith perspectives, this cannot be the mission or activity of programming that is funded with public monies. Additionally, the concept of informed consent is an important consideration. There may be an “assumed informed consent” that services will include prayer or scripture or other religious practices in religiously affiliated agencies or contexts of practice. That assumption may or may not be accurate. It is important that the social worker make clear what practices are utilized in the services that are offered so clients may choose or not choose to participate.

For instance, in a faith-affiliated hospital, the patient/client may be asked to sign an informed consent that acknowledges awareness that hospital staff may include prayer with them as part of treatment services. In a faith-affiliated children’s home, programming may include church service attendance by children in care. Some congregational settings providing counseling or other therapeutic services include signed informed consent that prayer, the use of religious texts and other religious services are part of the therapeutic package.

11. Field in Congregations and RAOs at One School of Social Work

The authors work in one of more than 700 social work education programs accredited by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). Their setting has included baccalaureate social work education since 1969 and graduate social work education since 1999, both programs continuously accredited by CSWE. The school’s mission statement is “to prepare students in a Christian context for excellence in professional social work practice and leadership in diverse settings worldwide” [

30] The program’s curriculum is centered on the competencies and practice behaviors of the CSWE with an additional competency which states: “The ethical integration of faith and practice” which is operationalized on the field program contract and evaluation by three core practice behaviors (the three legged stool):

Clients: Students will understand and work effectively with the religious, faith, and spirituality dimensions of persons and communities.

Students: Students will examine their own religious and spiritual frameworks and know how these aspects of self may inform and conflict with their social work practice.

Context: Students will understand and work effectively within the context of the practice setting in regard to faith and spirituality [

30].

The faith and practice competency is taught in an infusion model throughout the curriculum and evaluated both in the classroom coursework and in the field education program including the final field evaluation. Students in the Baccalaureate in Social Work (BSW) program complete a minimum of 480 h over two semesters in the field; students in the Master of Social Work (MSW) program complete a minimum of 1000 h, over two years (foundation and concentration) in the field. Internships are available in traditional and non-sectarian public settings and in congregations and religiously-affiliated organizations.

In 2008, the social work program identified more than 80 agencies in the local area for both BSW and MSW placements. In recent years with distance education, the program has expanded field internship sites across the United States and in some international settings. Criteria for field education sites include: provision of social services that meet the social work scope of service; provision directly or indirectly of supervision of students including social work supervision; and participation in field program training with respect to curriculum, internship roles and tasks, and supervision requirements.

Table 1 reveals that approximately 30% of the BSSW internship placements are in faith-based (congregational and RAO) organizations within the BSW and MSW programs.

12. Two Congregationally-Related Field Models

The program’s curriculum structures the integration of religious faith and practice by instruction focusing on the 10th competency (faith and practice) and the related practice behaviors as well as intentional development of field internships in congregational and RAOs. This emphasis is not instead of traditional social work field education but is an additional area of social work practice and competence that returns to the roots of the profession. It is consistent with the mission of the program, and develops competency in professional social work practice in systems that benefit from students and supervisors in the field. As a result of the emphasis of the integration of religious faith and practice, increasing numbers of students are interested in field internships in RAOs. The program has worked to develop field education opportunities in RAOs and congregations through several models.

13. One Congregation Model

A number of baccalaureate and graduate students have completed field internships in a single congregation with task supervision provided by the clergy or one of the ministers and field instruction provided by a licensed social worker within the congregation. These internships have been both micro/direct practice and macro/organizational and community practice. Several students have worked specifically with benevolence ministries or with senior adult ministries. With no on-staff social worker to provide field supervision, the school’s program approved a task supervisor for on-site supervisor with a contracted off-site social work field instructor.

There are numerous narratives of the significant ways the students in one of these placements impacted the congregation and community. For example, one student, in a generalist practice congregational placement, discovered in the benevolence ministry that the church had a $300 a month budget for helping with identified financial needs which was spent the first day of each month, almost always on someone who had received help on multiple occasions over the year. The remaining days of the month were filled with requests, no resources, regrets, and frustration. Those who called for help expressed frustration that there was no money left. The church members expressed frustration that despite their benevolence, they felt taken advantage of and not appreciated. In the midst of this, the student, with the field instructor’s help, developed and implemented a two pronged approach: (a) case management for every person who called in requesting financial assistance including a comprehensive assessment, strong referral network, and budget counseling, and (b) a church commitment to support one family a year with assessment, case management, family counseling, job training and placement, budget counseling and $300 a month assistance for the year. The generalist practice internship in the congregation became both a more effective method for providing “benevolence” and a macro practice approach to systems resources. Since then, the congregation has used this approach primarily with families with children. Additionally, this particular congregation has been a field internship placement site for several MSW students.

Strengths. The possible models for social work in one congregational setting seem endless with the micro, mezzo, and macro work that is a part of most congregations. These opportunities present both strengths and challenges in a setting where much work is done by numerous people who are responding to their faith through opportunities of service and where the motivational models are often based in religious texts rather than codes of ethics. There is significant strength in social workers who have been educationally prepared for this work to provide professional expertise for the services the church is already providing. Social workers who are trained in assessment, intervention, and evaluation are an asset to a helping process that includes both services and referral. A strength is the potential increase in efficiency and effectiveness for social services in congregations. Further, social workers are prepared to evaluate the effectiveness of programming and make needed changes. Additionally, the social work commitment to valuing all persons and providing ethical practice facilitates congregational participation in social justice practices including both fair processes and community engagement.

Limitations. As a fairly new phenomenon in the current age, social workers hired in a congregation face the limitation of role definition, much like they have faced in other secondary service settings like schools and hospitals. This can be challenging for the “only social worker” in a practice setting. Congregational social workers work with those from the neighborhood, other congregations, social agencies and local government. When they work with congregants with whom they worship, they may experience a dual relationship requiring role clarification and use of supervision. This complexity is not unlike that of rural social workers in small communities.

14. Rotational Model

In addition to the one congregation internship model, the program also designed and implemented a rotational, multiple site model which included student internship experiences in multiple agencies including congregation(s) over the course of the internship. This innovation occurred as part of the school’s advanced placement opportunities for MSW students interested in preparation for practice with older persons, offered with funding provided by the Hartford Foundation’s initiative to support the preparation of geriatric social workers. Many congregations include an older adult ministry for seniors who are ill, homebound, and/or are in residential placement. Occasionally, this ministry extends to include grief support, facilitating senior trips and activities, and caregiver ministry. The challenges of exposing social work students to professional opportunities in congregations including grief counseling, support for caregiving responsibilities and social skills and relationships in older adulthood can be maximized through the implementation of a rotational internship model.

In this model, a cohort of students (8–10) is assigned to a primary social service agency setting with a rotation of several days in the other seven to nine agencies during the semester. Additionally, each student in a primary internship setting hosts each of his/her peers for several days and carves out learning and practice opportunities for them. For example, the student who is in an internship placement in the Area Agency for Aging facilitates peers’ exposure to home visits, making referrals for adult day care or respite services while the student in a hospital setting on the geriatric unit facilitates peers’ experiences with end of life conversations, discharge planning to skilled nursing facilities, and family conferences for care planning. The student in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) facilitates peers’ experiences with family members through adjusting to visits in the SNF by including approaches like reminiscence therapy to enhance their visits. Conversely, the student in a congregational placement facilitates peers’ experiences with home visits of homebound older adults, grief counseling, and organizing the Senior Adult annual banquet. All of these serve as examples of solid social work practice in these settings.

The rotational model includes significant collaboration among the agencies. The field education program assists the agencies in identifying common training needs, policies, and task preparation. The agencies participate with hosting training that includes intake/admission/assessment forms, tasks they share in common and those that are unique to their respective agencies. The training includes identifying possible tasks for students rotating through the agency and the educational experience which is available to the student who is facilitating their peers’ experiences. Agency directors meet several times during the year to evaluate the collaboration and needs for communication and planning together for student experiences. One benefit to agencies and administrators is preparation of 8–10 students who are prepared to work in their agencies after graduation.

As students host their peers’ by including arranging for their learning experiences, their depth of learning is significant and includes collegial consultation and supervision. They become the negotiator of internship duties. For example, one student was able to organize peers’ facilitation of a psycho-educational group; a second student organized the home visits and assessments for in-home services which were done by peers; and a third student organized opportunities for peers to meet with older adults entering end of life care for end of life decision making conversations about living wills, medical power of attorneys, etc. These are just three examples. Students share an internship seminar which meets weekly to share the similar and disparate learning, the differences in policies across the 8–10 agency spectrum, and the impact of federal and state policies and reimbursement procedures. The rotational model provides one student with a deep experience in congregational social work with older adults and seven to nine others with a significant exposure to the possibilities in this new area of practice.

Strengths. The strengths of the rotational model are significant as students prepare for a variety of contexts of practice, enhance their resumes, and gain consultative experience. Agencies have a larger pool of trained, prepared interns to consider for employment openings and streamline referral processes for shared clients. The field education program gains field placement sites as agencies that are not able to provide some needed experiences are supplemented with rotational agencies. The challenges and opportunities around role and purpose and the integration of faith and practice became more evident and the discussions were both rich and productive.

Students in the program reported that the learning was rich, the collegial relationships lasted well beyond the internship experience, and the rotational model was a real benefit on their resume during the job search process. Agency personnel reported the benefits of developing streamlined referral processes among agencies, adapting policies to avoid the duplication of work, and the benefits of having a pool of trained social workers in the job pool when they were ready to hire a social worker. Congregational participants, including supervisors and pastors, responded to the rotational model with support for social work in the congregational setting. Students, supervisors, ministers, and congregants discovered, then, that the congregation was a legitimate and important context of practice for social workers, both those who shared the faith belief system of the congregation and those who did not. This model, operationalized over a period of three years, provides important information in the ongoing discussion around the use of congregations and other non-traditional settings for field internship and social work practice sites.

Limitations. Limitations to the rotational model include additional administrative time requirements, some fragmentation of the internship experience, and substantive concerns about the lack of depth in some of the rotational placement sites. Administrators of agencies, field instructors, and field program faculty spend significantly more time developing and sustaining the rotational model than is spent in the one student per agency model. The field liaison has the critical role of coordinating this learning experience. Students have a primary agency but are out of that agency at least one day a week for more than half of the block internship as they rotate through other agencies. The field education program has more work to do with educating the agencies about each other, finding common policy, training and tasks and negotiating the rotational experience.

15. Implications and Recommendations

The social work profession has strong roots in congregations, beginning with multiple persons of faith who cared about orphans, families, the mentally ill, and those who were economically poor in their communities. While the profession sought credibility and evidence for outcome based work, there was some disavowing of religious beliefs and institutions, partially based on the concern that faith-informed professionals might impose their religious values on clients and agencies and systems. Over time, the combination of concern around ethical violations and an emphasis on positivism led to fewer social workers in congregations and more secularization of faith based or religiously affiliated agencies. The loss to the profession included an important context of practice, avoidance of instruction on the intentional ethical integration of religious faith and practice, and an absence of models for work in RAOs. The loss to congregations and RAOs included less evidence-informed and effective practice, unavailability of professionally trained and prepared staff to respond to the psychosocial needs of hurting congregants and community members, and in-accessibility of community resources due to lack of awareness and/or trust in the capacity to deliver services.

Over the past 15 years or so, there has been a return to consideration of spirituality and religion in social work practice [

23,

31]. Concurrently, some religiously affiliated programs took on the challenge and opportunity of revitalizing the integration of religious faith and practice and social work internships in congregations and RAOs [

3]. The profession has in the past 15 years begun an important conversation about religion and spirituality as part of each client’s cultural experience and the importance of culturally competent practice with all persons [

32]. Further, the recent revision of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [

33] includes religion and spirituality as part of culture in the assessment of mental health in persons. Programs like this have engaged in intentional work to operationalize the integration of religious faith and practice in ways that are ethical and respectful both of the values of the profession and the values of the congregational or RAO context of practice.

Internships, both single congregational and rotational, provide the opportunity for research around effectiveness of practice and a growing role for social workers in congregations and RAOs. The work of Garland and Yancey [

8] suggests that there are growing numbers of social workers in congregations, though their titles may be other than social worker. Continued study of both the prevalence of social workers in congregations and RAOs and their role and purpose will be important to understanding how best to equip these workers and how best to understand the potential and challenges of this trend. Social work educators, social work interns, and social workers who carve out this territory, new again to the profession, may work as the only social worker in a congregation or may work in rotational internships that allow experiences in a variety of settings including a congregation. They may work as case managers and therapists and counselors or they may work as program planners, community organizers, and policy advocates for the oppressed in communities. They may “minister” to congregants or to the ministers around them and to the people in the geographic community whose basic needs are being met through congregational social work practices. They are uniquely equipped to do this advanced generalist practice in ethical, evidence based responses that respect their context of practice.

16. Future Research

As more social work academic programs consider field internship placements in congregations and in religiously-affiliated organizations, there is opportunity to, with intentionality, evaluate the learning experience of students, the ethical issues and responses, and a variety of models and their effectiveness. In addition, the internship experience will be enriched by the findings of research aimed at understanding the role of social work across a variety of religions and faith perspectives.

We think that the three-component model for integration of religious faith and practice (faith of the client, faith/worldview of the social worker, and organizational context) provide a helpful theoretical basis for guiding the design and involvement of social workers within congregational and RAO settings. Placements in congregations and RAOs provide rich opportunities to test the efficacy of these formulations as well as identify best practices in these settings. Larson and Robertson), in a qualitative study of three BSW students in Christian based practicum settings, noted that “It is interesting that the students in the current study all identified a lack of fit between some theories and methods taught at the university and those practiced at the agencies” ([

20], p. 255). These and other questions are the rich ground for research available in the future. We recognize that additional research is needed in the application of these possibilities in organizational contexts affiliated with other religious traditions.

17. Summary and Conclusions

Eun-Kyoung and Barrett stated: “In recent decades, ‘increasing numbers of contemporary social work practitioners have expressed their needs to integrate their spirituality and religious faith into their professional activities’” ([

29], p. 354). This call for integration requires guidance from an accurate theoretical accounting for the nature of congregationally-based social work practice and a clear conceptualization of how ethical integration of faith and practice can occur with the internship experience. We offer a report of one school’s response to both of these conceptual and practical requirements. Whether faith and practice integration occurs in non-sectarian agencies or within RAOs and congregations, we anticipate that the urgency and relevance of this conversation will be increasing in concert with the growing recognition of religion and spirituality as cultural experiences and the expanding involvement of social workers in a variety of religious settings. With this in mind, the authors continue to explore approaches for internships in religious congregations and RAOs. These approaches are intended both to professionalize services in these settings, open new employment opportunities for social workers, enhance opportunities for social workers to integrate their religious faith and practice, and develop new models for this work.