Charitable Sporting Events as a Context for Building Adolescent Generosity: Examining the Role of Religiousness and Spirituality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

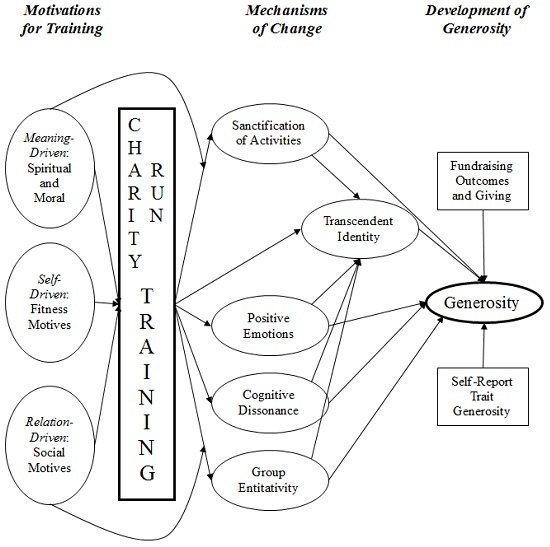

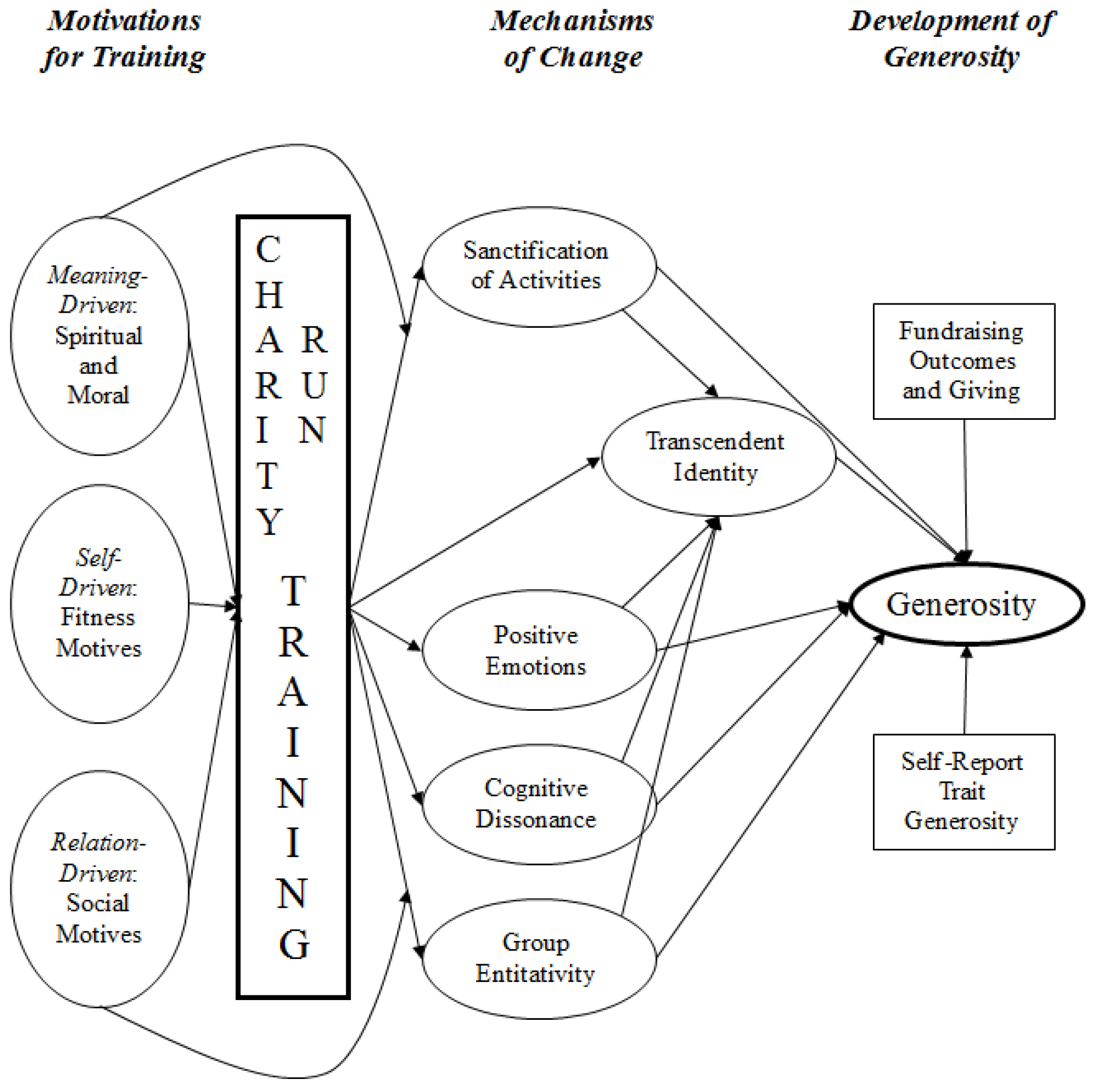

2. Theoretical Model

2.1. Predisposing Factors

2.2. Specific Mechanisms Active in Training

2.3. Higher-Order Mechanisms

2.3.1. Sanctification

2.3.2. Identity

2.4. Lower-Order Mechanisms

2.4.1. Increased Entitativity

2.4.2. Positive Emotionality in Marathon Participation

2.4.3. Dissonance Reduction

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary

3.2. Methodological Challenges

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- René Bekkers, and Pamala Wiepking. “Who gives? A literature review of predictors of charitable giving part one: Religion, education, age and socialization.” Voluntary Sector Review 2 (2011): 337–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke W. Galen. “Does religious belief promote prosociality? A critical examination.” Psychological Bulletin 138 (2012): 876–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanda Lenhart, Kristen Purcell, Aaron Smith, and Kathryn Zickuhr. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use among Teens and Young Adults. Millennials. Washington: Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Smith, and Jonathan P. Hill. “Toward the measurement of Interpersonal Generosity (IG): An IG scale conceptualized, tested, and validated.” 2009. Available online: https://generosityresearch.nd.edu/assets/13798/ig_paper_smith_hill_rev.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2016).

- Mark H. Davis. “Measuring individual difference in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (1983): 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter L. Benson. “Emerging themes in research on adolescent spiritual and religious development.” Applied Developmental Science 8 (2004): 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt Büssing, Axel Föller-Mancini, Jennifer Gidley, and Peter Heusser. “Aspects of spirituality in adolescents.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 15 (2010): 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy Eva Alberts Warren, Richard M. Lerner, and Erin Phelps, eds. Thriving and Spirituality among Youth: Research Perspectives and Future Possibilities. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Anthony G. James, and Mark A. Fine. “Relations between youths’ conceptions of spirituality and their developmental outcomes.” Journal of Adolescence 43 (2015): 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel S. Spiewak, and Lonnie R. Sherrod. “The shared pathways of religious/spiritual engagement and positive youth development.” In Thriving and Spirituality among Youth: Research Perspectives and Future Possibilities. Edited by Amy Eva Alberts Warren, Richard M. Lerner and Erin Phelps. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2012, pp. 167–81. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt Büssing, Philipp Kerksieck, Andreas Günther, and Klaus Baumann. “Altruism in adolescents and young adults: Validation of an instrument to measure generative altruism with structural equation modeling.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 18 (2013): 335–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim F. Shariff, and Ara Norenzayan. “God is watching you: Priming God concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous economic game.” Psychological Science 18 (2007): 803–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alethea Desrosiers, Brien S. Kelley, and Lisa Miller. “Parent and peer relationships and relational spirituality in adolescents and young adults.” Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3 (2011): 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naomi E. Feldman. “Time is money: Choosing between charitable activities.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2 (2010): 103–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter L. Benson, Peter C. Scales, Stephen F. Hamilton, and Arturo Sesma. Positive Youth Development: Theory, Research, and Applications. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roger Bennett, Wendy Mousley, Paul James Kitchin, and Rehnuma Ali-Choudhury. “Motivations for participating in charity-affiliated sporting events.” Journal of Customer Behavior 6 (2007): 155–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margo Gardner, and Laurence Steinberg. “Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study.” Developmental Psychology 41 (2005): 625–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carl J. Caspersen, Mark A. Pereira, and Katy M. Curran. “Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age.” Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise 32 (2000): 1601–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gian V. Caprara, Guido Alessandri, and Nancy Eisenberg. “Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102 (2012): 1289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard K. Caputo. “Religious capital and intergenerational transmission of volunteering as correlates of civic engagement.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38 (2009): 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraig Beyerlein, and John R. Hipp. “From pews to participation: The effect of congregation activity and context on bridging civic engagement.” Social Problems 53 (2006): 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth I. Pargament, and Annette M. Mahoney. “Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion.” The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 15 (2005): 179–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert A. Emmons, Chi Cheung, and Keivan Tehrani. “Assessing spirituality through personal goals: Implications for research on religion and subjective well-being.” Social Indicators Research 45 (1998): 391–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annette Mahoney, Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Tracey Jewell, Gina M. Magyar, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and Russell Phillips. “A higher purpose: The sanctification of strivings in a community sample.” The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 15 (2005): 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Vision. “Who We Are.” 2015. Available online: http://www.worldvision.org/about-us/who-we-are (accessed on 21 January 2016).

- Erik H. Erikson. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: WW Norton, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Elisabetta Crocetti, Rasa Erentaitė, and Rita Žukauskienė. “Identity styles, positive youth development, and civic engagement in adolescence.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43 (2014): 1818–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James L. Furrow, Pamela E. King, and Krystal White. “Religion and positive youth development: Identity, meaning, and prosocial concerns.” Applied Developmental Science 8 (2004): 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan P. McAdams, and Jennifer Lilgendahl Pals. “A new big five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality.” American Psychologist 61 (2006): 208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert R. McCrae, and Paul T. Costa. “The five-factor theory of personality.” In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Edited by Oliver P. John, Richard W. Robins and Lawrence A. Pervin. New York: Guilford, 2008, pp. 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jack J. Bauer, Dan P. McAdams, and Jennifer L. Pals. “Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (2008): 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan P. McAdams. “Generativity in midlife.” In Handbook of Midlife Development. Edited by Margie E. Lachman. New York: Wiley, 2001, pp. 395–443. [Google Scholar]

- Brian Lickel, David L. Hamilton, Grazyna Wieczorkowska, Amy Lewis, Steven J. Sherman, and A. Neville Uhles. “Varieties of groups and the perception of group entitativity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78 (2000): 223–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sophia Jowett, and Victoria Chaundy. “An investigation into the impact of coach leadership and coach-athlete relationship on group cohesion.” Group Dynamics, Theory, Research, and Practice 8 (2004): 302–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Bernhard, Urs Fischbacher, and Ernst Fehr. “Parochial altruism in humans.” Nature 442 (2006): 912–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William B. Harrison, Shannon K. Mitchell, and Steven P. Peterson. “Alumni donations and colleges’ development expenditures: Does spending matter? ” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 54 (1995): 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly A. Marr, Charles H. Mullin, and John J. Siegfried. “Undergraduate financial aid and subsequent alumni giving behavior.” The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 45 (2005): 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih-Ying Wu, Jr-Tsung Huang, and An-Pang Kao. “An analysis of the peer effects in charitable giving: The case of Taiwan.” Journal of Family and Economic Issues 25 (2004): 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Sosis, and Eric R. Bressler. “Cooperation and commune longevity: A test of the costly signaling theory of religion.” Cross-Cultural Research 37 (2003): 211–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara L. Fredrickson. “The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions.” American Psychologist 56 (2001): 218–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David DeSteno, Monica Y. Bartlett, Jolie Baumann, Lisa A. Williams, and Leah Dickens. “Gratitude as moral sentiment: Emotion-guided cooperation in economic exchange.” Emotion 10 (2010): 289–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenneth R. Fox. “The influence of physical activity on mental well-being.” Public Health Nutrition 2 (1999): 411–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank J. Penedo, and Jason R. Dahn. “Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18 (2005): 189–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew P. Tix, and Patricia A. Frazier. “Mediation and moderation of the relationship between intrinsic religiousness and mental health.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31 (2005): 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peggy A. Thotis. “Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers.” Social Psychology Quarterly 75 (2012): 360–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William T. Hallam, Craig A. Olsson, Meredith O’Connor, Mary Hawkins, John W. Toumbourou, Glenn Bowes, Rob McGee, and Ann Sanson. “Association between adolescent eudaimonic behaviours and emotional competence in young adulthood.” Journal of Happiness Studies 15 (2014): 1165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura B. Aknin, Christopher P. Barrington-Leigh, Elizabeth W. Dunn, John F. Helliwell, Justine Burns, Robert Biswas-Diener, Imelda Kemeza, Paul Nyende, and Michael I. Norton. “Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104 (2015): 635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William T. Harbaugh, Ulrich Mayr, and Daniel R. Burghart. “Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations.” Science 316 (2007): 1622–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laura B. Aknin, Elizabeth W. Dunn, and Michael I. Norton. “Happiness runs in a circular motion: Evidence for a positive feedback loop between prosocial spending and happiness.” Journal of Happiness Studies 13 (2012): 347–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon Festinger. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Palo AltoStanford: Stanford University Press, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Running USA. “2014 Annual Marathon Report.” 2014. Available online: http://www.runningusa.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=news.details&ArticleId=332 (accessed on 21 January 2016).

- Sarah Klein. “26 Reasons not to Run a Marathon.” The Huffington Post. 2013. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/10/29/why-not-shouldnt-run-marathon_n_4171186.html (accessed on 21 January 2016).

- Richard D. Waters. “Examining the role of cognitive dissonance in crisis fundraising.” Public Relations Review 35 (2009): 139–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernandez, N.A.; Schnitker, S.A.; Houltberg, B.J. Charitable Sporting Events as a Context for Building Adolescent Generosity: Examining the Role of Religiousness and Spirituality. Religions 2016, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030035

Fernandez NA, Schnitker SA, Houltberg BJ. Charitable Sporting Events as a Context for Building Adolescent Generosity: Examining the Role of Religiousness and Spirituality. Religions. 2016; 7(3):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030035

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandez, Nathaniel A., Sarah A. Schnitker, and Benjamin J. Houltberg. 2016. "Charitable Sporting Events as a Context for Building Adolescent Generosity: Examining the Role of Religiousness and Spirituality" Religions 7, no. 3: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030035