Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Alpha-5 Promotes Radioresistance via Recruiting E2F Activity in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSC) Patients and Data Processing

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)

2.4. Western Blotting Assay

2.5. Preparation and Infection of Lentiviral Particle

2.6. Irradiation Treatment and Cell Viability Analysis

2.7. Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. CHRNA5 Upregulation Is Dominant in Primary Tumors Compared to Normal Tissues Derived from Patients with HNSCC

3.2. CHRNA5 Upregulation Predicts a Poorer Prognosis in OSCC Patients Compared to Non-OSCC Patients

3.3. CHRNA5 Upregulation Is Associated with a Poor Response to Radiotherapy in OSCC Patients

3.4. CHRNA5 Upregulation is Significantly Correlated with Radiosensitivity in OSCC Cells

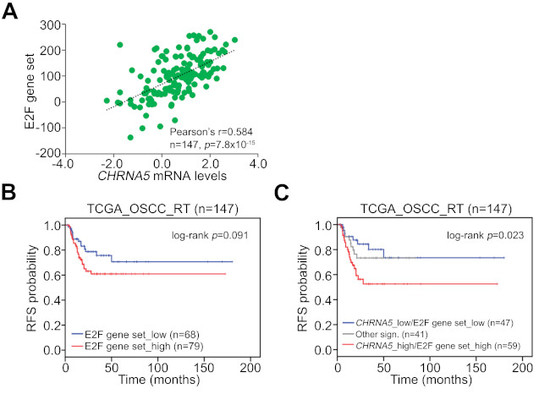

3.5. CHRNA5 Upregulation/Activation Enhances E2F Activity in OSCC Cells

3.6. Upregulation of the CHRNA5–E2F Axis Predicts Worse Prognosis in OSCC Patients Receiving Radiotherapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bagan, J.; Sarrion, G.; Jimenez, Y. Oral cancer: Clinical features. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.J.; Jiang, R.S.; Wu, S.H.; Chen, F.J.; Liu, S.A. Smoking, alcohol, and betel quid and oral cancer: A prospective cohort study. J. Oncol. 2011, 2011, 525976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, S.; Ang, K.K.; Vermorken, J.; Haddad, R.; Suarez, C.; Wolf, G.T.; Hamoir, M.; Machiels, J.P. Targeted therapies for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Current knowledge and future directions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.H.; O’Sullivan, B. Oral cancer: Current role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2013, 18, e233–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brejc, K.; van Dijk, W.J.; Klaassen, R.V.; Schuurmans, M.; van Der, O.J.; Smit, A.B.; Sixma, T.K. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 2001, 411, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, E.X.; Pereira, E.F.; Alkondon, M.; Rogers, S.W. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 73–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneric, S.P.; Holladay, M.; Williams, M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: A perspective on two decades of drug discovery research. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Improgo, M.R.; Scofield, M.D.; Tapper, A.R.; Gardner, P.D. From smoking to lung cancer: The CHRNA5/A3/B4 connection. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4874–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, G.K.; Williams, M. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as novel drug targets. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, M.N.; Gratteri, P.; Guandalini, L.; Martini, E.; Bonaccini, C.; Gualtieri, F. Central nicotinic receptors: Structure, function, ligands, and therapeutic potential. ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 746–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.W.; Wang, G.N.; Dong, Z.Z.; Li, T.H.; Cao, C.; Jin, Y.H. CHRNA5 rs16969968 Polymorphism Association with Risk of Lung Cancer—Evidence from 17,962 Lung Cancer Cases and 77,216 Control Subjects. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 6685–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.S.; Hung, R.J.; Baker, T.; Horton, A.; Culverhouse, R.; Saccone, N.; Cheng, I.; Deng, B.; Han, Y.; Hansen, H.M. CHRNA5 risk variant predicts delayed smoking cessation and earlier lung cancer diagnosis--a meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajesh, D.; Mohiyuddin, S.M.A.; Balakrishna, S.; Kutty, A.V.M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene polymorphism is not associated with tobacco-related oral squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J. Cancer 2018, 55, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldman, M.; Craft, M.; Hastie, M.; Repečka, K.; Kamath, A.; McDade, F.; Rogers, D.; Brooks, A.N.; Zhu, J.; Haussler, D. The UCSC Xena platform for public and private cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. bioRxiv 2019, 326470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. PNAS 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budczies, J.; Klauschen, F.; Sinn, B.V.; Gyorffy, B.; Schmitt, W.D.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Denkert, C. Cutoff Finder: a comprehensive and straightforward Web application enabling rapid biomarker cutoff optimization. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramqvist, T.; Grün, N.; Dalianis, T. Human papillomavirus and tonsillar and base of tongue cancer. Viruses 2015, 7, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.A.; Kiang, A.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Rahimy, E.; Haas, M.; Yu, V.; Ellies, L.G.; Chen, J.; Fan, J.B.; Brumund, K.T.; et al. Nicotine promotes acquisition of stem cell and epithelial-to-mesenchymal properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, R.; Ibaragi, S.; Eguchi, T.; Kuwajima, D.; Kodama, S.; Nishioka, T.; Okui, T.; Obata, K.; Takabatake, K.; Kawai, H.; et al. Nicotine promotes lymph node metastasis and cetuximab resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Niu, W.; Qi, M.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Ge, L.; Yang, J.; Miao, C.; Shi, N.; et al. Nicotine promotes cervical metastasis of oral cancer by regulating peroxiredoxin 1 and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mice. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 3327–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Tada, H.; Ibaragi, S.; Chen, C.; Sasano, T. Nicotine exposure induces the proliferation of oral cancer cells through the alpha7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 509, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Le, W.; Yee, A.; Kamdar, O.; Hwang, P.H.; Upadhyay, D. Nicotine induces resistance to chemotherapy in nasal epithelial cancer. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2010, 24, e73–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, H.; Pan, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Nicotine inhibits apoptosis induced by cisplatin in human oral cancer cells. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.P.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Yadav, S.; Singh, S.R.; Shukla, S. Integrated genomic analyses identify KDM1A’s role in cell proliferation via modulating E2F signaling activity and associate with poor clinical outcome in oral cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 367, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.G.; Ramalho, L.M.; Gaiao, L.; Pozza, D.H.; de Mello, R.A. Retinoblastoma and p53 protein expression in pre-malignant oral lesions and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2012, 6, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Meng, A.M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.H.; Wang, X.C.; Zhai, Z.B.; Fu, Y.; et al. Retinoblastoma 94 enhances radiation treatment of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. J. Radiat. Res. 2012, 53, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Araki, K.; Ahmad, S.M.; Li, G.; Bray, D.A., Jr.; Saito, K.; Wang, D.; Wirtz, U.; Sreedharan, S.; O’Malley, B.W., Jr.; Li, D. Retinoblastoma RB94 enhances radiation treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 3514–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P.; Rizwani, W.; Pillai, S.; Davis, R.; Banerjee, S.; Hug, K.; Lloyd, M.; Coppola, D.; Haura, E.; Chellappan, S.P. ARRB1-mediated regulation of E2F target genes in nicotine-induced growth of lung tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recurrence-free survival (n = 305) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Crude HR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p |

| age | ||||

| < 60 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| ≥ 60 | 1.27 (0.81–1.98) | 0.301 | 1.46 (0.91–2.36) | 0.117 |

| gender | ||||

| female | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| male | 1.08 (0.64–1.81) | 0.781 | 1.06 (0.61–1.84) | 0.842 |

| pT | ||||

| T1–T2 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| T3–T4 | 1.82 (1.11–2.98) | 0.018 | 1.47 (0.87–2.49) | 0.150 |

| pN | ||||

| N0 | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| N1–N3 | 1.72 (1.07–2.76) | 0.024 | 1.55 (0.92–2.259) | 0.097 |

| stage | ||||

| I–II | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| III–IV | 2.38 (1.19–4.76) | 0.015 | NA | NA |

| treatment | ||||

| none | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| RT | 1.27 (0.75–2.28) | 0.428 | 1.04 (0.56–1.92) | 0.909 |

| RT + TarT | 1.52 (0.86–2.68) | 0.150 | 1.22 (0.63–2.36) | 0.549 |

| smoker | ||||

| no | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| yes | 1.32 (0.75–2.32) | 0.337 | 1.10 (0.60–2.03) | 0.762 |

| subdivision | ||||

| non-OSCC | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| OSCC | 1.04 (0.66–1.66) | 0.855 | 1.28 (0.78–2.10) | 0.321 |

| CHRNA5 level | ||||

| low | 1 | NA | 1 | NA |

| high | 1.87 (1.20–2.91) | 0.006 | 1.82 (1.15–2.88) | 0.011 |

| Clinicopathological Characteristics | n | CHRNA5 Expression, n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 199) | High (n = 106) | |||

| age | ||||

| < 60 | 151 | 92 (60.9%) | 59 (39.1%) | |

| ≥ 60 | 154 | 107 (69.5%) | 47 (30.5%) | 0.120 |

| gender | ||||

| female | 82 | 57 (69.5%) | 25 (30.5%) | |

| male | 223 | 142 (63.7%) | 81 (36.3%) | 0.416 |

| pT | ||||

| T1–T2 | 119 | 89 (74.8%) | 30 (25.2%) | |

| T3–T4 | 186 | 110 (59.1%) | 76 (40.9%) | 0.007 |

| pN | ||||

| N0 | 133 | 95 (71.4%) | 38 (28.6%) | |

| N1–N3 | 172 | 104 (60.5%) | 68 (39.5%) | 0.053 |

| stage | ||||

| I–II | 63 | 49 (77.8%) | 14 (22.2%) | |

| III–IV | 242 | 150 (62.0%) | 92 (38.0%) | 0.019 |

| smoker | ||||

| no | 72 | 55 (76.4%) | 17 (23.6%) | |

| yes | 233 | 144 (61.8%) | 89 (38.2%) | 0.024 |

| subdivision | ||||

| non-OSCC | 108 | 60 (55.6%) | 48 (44.4%) | |

| OSCC | 197 | 139 (70.6%) | 58 (29.4%) | 0.012 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.-H.; Lee, H.-H.; Kuei, C.-H.; Lin, H.-Y.; Lu, L.-S.; Lee, F.-P.; Chang, J.; Wang, J.-Y.; Hsu, K.-C.; Lin, Y.-F. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Alpha-5 Promotes Radioresistance via Recruiting E2F Activity in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091454

Lin C-H, Lee H-H, Kuei C-H, Lin H-Y, Lu L-S, Lee F-P, Chang J, Wang J-Y, Hsu K-C, Lin Y-F. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Alpha-5 Promotes Radioresistance via Recruiting E2F Activity in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(9):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091454

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Che-Hsuan, Hsun-Hua Lee, Chia-Hao Kuei, Hui-Yu Lin, Long-Sheng Lu, Fei-Peng Lee, Jungshan Chang, Jia-Yi Wang, Kai-Cheng Hsu, and Yuan-Feng Lin. 2019. "Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Alpha-5 Promotes Radioresistance via Recruiting E2F Activity in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 9: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091454

APA StyleLin, C.-H., Lee, H.-H., Kuei, C.-H., Lin, H.-Y., Lu, L.-S., Lee, F.-P., Chang, J., Wang, J.-Y., Hsu, K.-C., & Lin, Y.-F. (2019). Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Subunit Alpha-5 Promotes Radioresistance via Recruiting E2F Activity in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(9), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8091454