Blacks’ Diminished Return of Education Attainment on Subjective Health; Mediating Effect of Income

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Surveys

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Independent Variables

2.5.2. Dependent Variable

2.5.3. Covariates

2.5.4. Moderator

2.5.5. Mediator

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

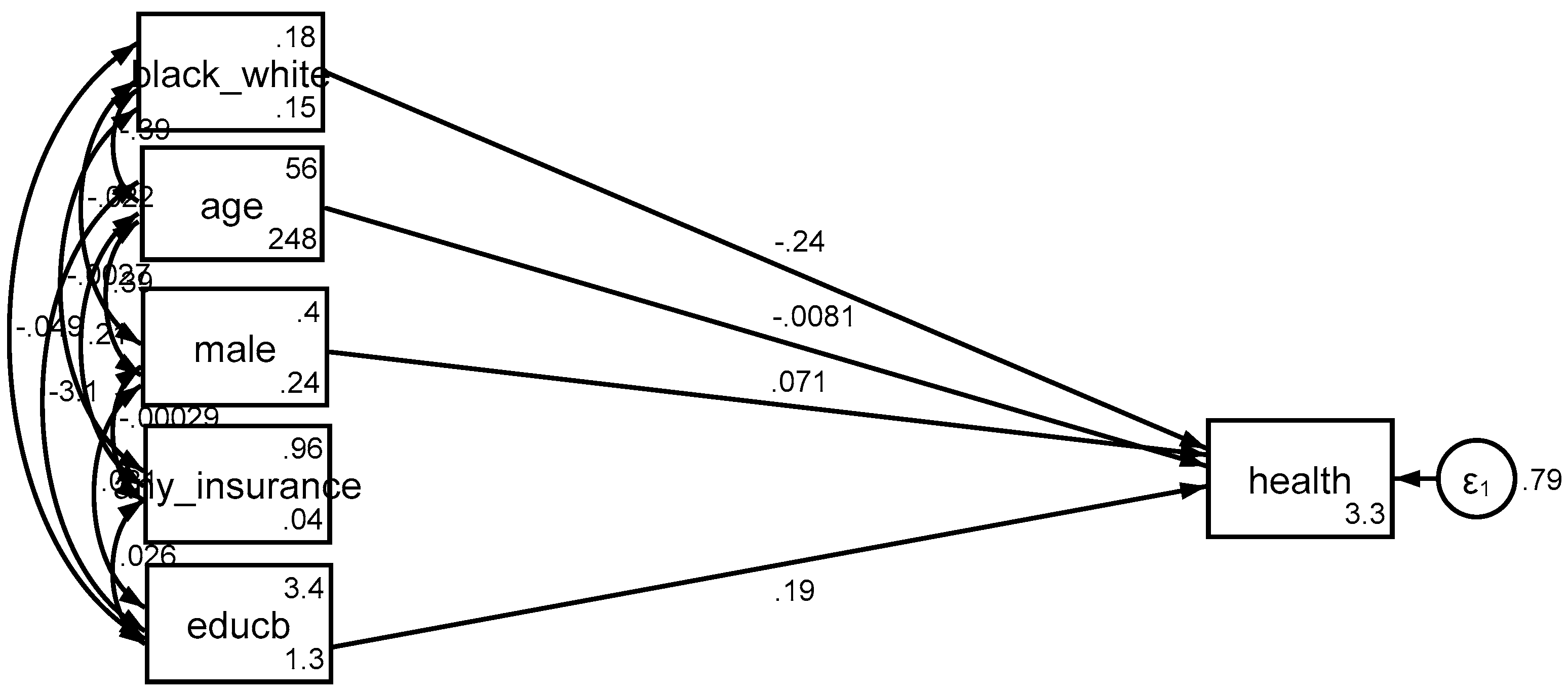

3.2. Multivariable Models

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marmot, M.G.; Shipley, M.J. Do socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. Br. Med. J. 1996, 313, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Groenou, M.I.B.; Deeg, D.J.; Penninx, B.W. Income differentials in functional disability in old age: Relative risks of onset, recovery, decline, attrition and mortality. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 15, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, C.S.; Gurland, B.J. The relationship among income, other socioeconomic indicators, and functional level in older persons. J. Aging Health 1998, 10, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.P.; Leon, J.; Smith Greenaway, E.G.; Collins, J.; Movit, M. The education effect on population health: A reassessment. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2011, 37, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodish, P.H.; Massing, M.; Tyroler, H.A. Income inequality and all-cause mortality in the 100 counties of North Carolina. South Med. J. 2000, 93, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herd, P.; Goesling, B.; House, J.S. Socioeconomic position and health: The differential effects of education versus income on the onset versus progression of health problems. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007, 48, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzer, C.; Shea, B.; Swanson, J.; Leaf, P.; Myers, J.; George, L.; Weissman, M.; Bednarski, P. The increased risk for specific psychiatric disorders among persons of low socioeconomic status: Evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Surveys. Am. J. Soc. Psychiatry 1986, 4, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M.; Bruce, M.; Leaf, P.; Florio, L.; Holzer, C. Affective Disorders. In Psychiatric Disorders in America; Robins, K., Reiger, D., Eds.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Reiger, D.; Farmer, M.; Rae, D.; Myers, J.; Kramer, M.; Robins, L.; George, L.; Karno, M.; Locke, B. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1993, 88, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, M.; Bijl, R.; Lin, E.; Walters, E.; Kessler, R. Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: A comparison of the United States with Ontario and The Netherlands. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazer, D.; George, K.; Landerman, R.; Pennybacker, M.; Melville, M.; Woodbury, M.; Manton, K.; Jordan, K.; Locke, B. Psychiatric disorders: A rural/urban comparison. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1985, 42, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leaf, P.; Weissman, M.; Myers, J.; Holzer, C.; Tischler, G. Psychosocial risks and correlates of major depression in one United States urban community. In Mental Disorders in the Community: Progress and Challenge; Barrett, D., Rose, R., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, M.; Takeuchi, D.; Leaf, P. Poverty and psychiatric status: Longitudinal evidence from the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1991, 48, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.; Zhao, S.; Blazer, D.; Swartz, M. Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the national comorbidity survey. J. Affect. Disord. 1997, 45, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.; Rush, J.; Walters, E.; Wang, P. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003, 289, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, M.J.; Kim, H.; Matthews, W.J. Predicting self-rated mental and physical health: The contributions of subjective socioeconomic status and personal relative deprivation. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, O.L.; Castro-Schilo, L.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: A model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Demographic and Socioeconomic Determinants of Physical and Mental Self-rated Health across 10 Ethnic Groups in the United States. Int. J. Epidemiol. Res. 2017, 4, 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, A.I.; Weekley, C.C.; Chen, S.C.; Li, S.; Tamura, M.K.; Norris, K.C.; Shlipak, M.G. Association of educational attainment with chronic disease and mortality: The Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gakidou, E.; Cowling, K.; Lozano, R.; Murray, C.J. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2010, 376, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Racial Variation in the Association between Educational Attainment and Self-Rated Health. Societies 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Preiser, B.; Kelly, M. Education and Income Predict Future Emotional Well-Being of Whites but Not Blacks: A Ten-Year Cohort. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Moghani Lankarani, M. Poverty Status and Childhood Asthma in White and Black Families: National Survey of Children’s Health. Healthcare 2018, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Family Income Reduces Risk of Obesity for White but Not Black Children. Children 2018, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H.; Zimmerman, M.A. Family Structure and Subsequent Anxiety Symptoms; Minorities’ Diminished Return. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Combined racial and gender differences in the long-term predictive role of education on depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2016, 4, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Race and urbanity alter the protective effect of education but not income on mortality. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Education and alcohol consumption among older Americans. Black-White Differences. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Health Disparities Due to Diminished Return among Black Americans: Public Policy Solutions. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2018, 12, 112–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Unequal gain of equal resources across racial groups. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Life expectancy gain due to employment status depends on race, gender, education, and their intersections. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H. Social Determinants of Perceived Discrimination among Black Youth: Intersection of Ethnicity and Gender. Children 2018, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Thomas, A.; Caldwell, C.H.; Mincy, R.B. Blacks’ Diminished Health Return of Family Structure and Socioeconomic Status; 15 Years of Follow-up of a National Urban Sample of Youth. J. Urban Health 2017, 95, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Social Determinants of Depression: The Intersections of Race, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, M.M.; Ferraro, K.F. Are racial disparities in health conditional on socioeconomic status? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. The Benefits of Higher Income in Protecting against Chronic Medical Conditions Are Smaller for African Americans than Whites. Healthcare 2018, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Gibbons, F.X.; Simons, R. Depression among Black Youth; Interaction of Class and Place. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Gibbons, F.X.; Simons, R.L. Perceived Discrimination among Black Youth: An 18-Year Longitudinal Study. Behav. Sci. (Basel) 2018, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M.; Caldwell, C.H. Does Discrimination Explain High Risk of Depression among High-Income African American Men? Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Preiser, B.; Lankarani, M.M.; Caldwell, C.H. Subjective Socioeconomic Status Moderates the Association between Discrimination and Depression in African American Youth. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Parental Education Better Helps White than Black Families Escape Poverty: National Survey of Children’s Health. Economies 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. Diminished Economic Return of Socioeconomic Status for Black Families. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H. High Risk of Depression in High-Income African American Boys. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2018, 5, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, A.R.; Walton, E.; Chae, D.H.; Alegria, M.; Jackson, J.S.; Takeuchi, D. The associations between socio-economic status and major depressive disorder among Blacks, Latinos, Asians and non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, B.W.; Moser, R.P.; Rutten, L.J.; Kreps, G.L. The health information national trends survey: Research from the baseline. J. Health Commun. 2006, 11, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey 5 (HINTS 5) Cycle 1 MethodologyReport.2017. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle_1_Methodology_Rpt.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). State of the USA Health Indicators: Letter Report. 2009. Available online: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12534/state-of-the-usa-healthindicators-letter-report (accessed on 1 April 2018).

- Abdulrahim, S.; El Asmar, K. Is self-rated health a valid measure to use in social inequities and health research? Evidence from the PAPFAM women’s data in six Arab countries. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reichmann, W.M.; Katz, J.N.; Kessler, C.L.; Jordan, J.M.; Losina, E. Determinants of self-reported health status in a population-based sample of persons with radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mossey, J.M.; Shapiro, E. Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am. J. Public Health 1982, 72, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyamini, Y.; Idler, E.L. Community studies reporting association between self-rated health and mortality: Additional studies, 1995 to 1998. Res. Aging 1999, 21, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, K.B.; Bloser, N.; Reynolds, K.; He, J.; Muntner, P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, J.M.N.; Chor, D.; Werneck, G.L.; Carvalho, M.S.; Coeli, C.M.; Lopes, C.S.; Faerstein, E. Association between self-rated health and mortality: 10 years follow-up to the Pró-Saúde cohort study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Promise and pitfalls of structural equation modeling in gifted research. In Methodologies for Conducting Research on Giftedness; Thompson, B., Subotnik, R.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, P.D. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 18 User’s Guide; Amos Development Corporation: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Bouchard, C.; Bray, G.A.; Greenway, F.L.; Johnson, W.D.; Newton, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Ryan, D.H.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Trunk versus extremity adiposity and cardiometabolic risk factors in white and African American adults. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, M.; Lomax, R.G. The effect of varying degrees of nonnormality in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2005, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Diez-Roux, A.; Kawachi, I.; Levin, B. “Fundamental causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Northridge, M.E.; Phelan, J.C.; Ganz, M.L. Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: On the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Q. 1998, 76, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.J. Social determinants of health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S517–S519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Ethnic and Gender Differences in Additive Effects of Socio-economics, Psychiatric Disorders, and Subjective Religiosity on Suicidal Ideation among Blacks. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehkopf, D.H.; Buka, S.L. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purselle, D.C.; Heninger, M.; Hanzlick, R.; Garlow, S.J. Differential association of socioeconomic status in ethnic and age-defined suicides. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 167, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goodman, E.; Huang, B. Socioeconomic status, depressive symptoms, and adolescent substance use. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, R.; Kann, L.; Collins, J.L.; Kolbe, L.J. The effect of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1996, 276, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Mirowsky, J. Education, Social Status, and Health (Social Institutions and Social Change); Aldine Transaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, M.D.; Hummer, R.A.; Sasson, I. Trends and group differences in the association between educational attainment and U.S. adult mortality: Implications for understanding education’s causal influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 127, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backlund, E.; Sorlie, P.D.; Johnson, N.J. A comparison of the relationships of education and income with mortality: The national longitudinal mortality study. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, B.G.; Rehkopf, D.H.; Rogers, R.G. The nonlinear relationship between education and mortality: An examination of cohort, race/ethnic, and gender differences. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, D.M.; Lleras-Muney, A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w12352 (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Holmes, C.J.; Zajacova, A. Education as “the great equalizer”: Health benefits for black and white adults. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 95, 1064–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Caldwell, C.H.; Mincy, R.B. Maternal Educational Attainment at Birth Promotes Future Self-Rated Health of White but Not Black Youth: A 15-Year Cohort of a National Sample. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Lapeyrouse, L.M.; Neighbors, H.W. Income and Self-Rated Mental Health: Diminished Returns for High Income Black Americans. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S. Socioeconomic Status and Self-Rated Oral Health; Diminished Return among Hispanic Whites. Dent. J. 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A.; Leavell, J.; Collins, C. Race, Socioeconomic Status and Health: Complexities, Ongoing Challenges and Research Opportunities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, E.R.; Omari, S.R. Race, class and the dilemmas of upward mobility for African Americans. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Kleiner, R.J. The culture of poverty: An adjustive dimension. Am. Anthropol. 1970, 72, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Dejman, M.; Neighbors, H.W. Ethnic Differences in Separate and Additive Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Self-rated Mental Health Among Blacks. J. Racial Ethn. Health Dispar. 2016, 3, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, S.E.; Mollborn, S. Social Determinants and Health Behaviors: Conceptual Frames and Empirical Advances. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bécares, L.; Nazroo, J.; Jackson, J. Ethnic density and depressive symptoms among African Americans: Threshold and differential effects across social and demographic subgroups. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 2334–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Wallace, G.; Wesner, K.A. Neighborhood Characteristics and Depression: An Examination of Stress Processes. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| b | SE | 95% CI | z | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Main Effect Model) | |||||||

| Age | Health | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −7.00 | 0.000 |

| Gender (Male) | Health | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 1.93 | 0.053 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) | Health | −0.24 | 0.05 | −0.34 | −0.14 | −4.87 | 0.000 |

| Education | Health | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 11.66 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | Health | 3.26 | 0.10 | 3.07 | 3.44 | 33.79 | 0.000 |

| Model 2 (Interaction Model) | |||||||

| Age | Health | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −7.00 | 0.000 |

| Gender (Male) | Health | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 1.90 | 0.057 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) | Health | −0.09 | 0.14 | −0.37 | 0.19 | −0.61 | 0.543 |

| Education | Health | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 10.86 | 0.000 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) × Education | Health | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | 0.03 | −1.15 | 0.249 |

| Intercept | Health | 3.22 | 0.10 | 3.03 | 3.42 | 32.01 | 0.000 |

| Model 7 (Income) | |||||||

| Income | Health | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 9.92 | 0.000 |

| Age | Health | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −5.84 | 0.000 |

| Gender (Male) | Health | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.596 |

| Health insurance | Health | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.22 | 0.12 | −0.55 | 0.583 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) | Health | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.20 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.583 |

| Education | Health | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 6.34 | 0.000 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) × Education | Health | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.02 | −1.42 | 0.155 |

| Intercept | Health | 2.90 | 0.13 | 2.65 | 3.14 | 23.09 | 0.000 |

| Age | Income | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −5.34 | 0.000 |

| Gender (Male) | Income | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.67 | 6.55 | 0.000 |

| Ethnicity (Blacks) | Income | −1.39 | 0.11 | −1.60 | −1.18 | −13.08 | 0.000 |

| Education | Income | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 23.02 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | Income | 3.70 | 0.21 | 3.29 | 4.11 | 17.76 | 0.000 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Assari, S. Blacks’ Diminished Return of Education Attainment on Subjective Health; Mediating Effect of Income. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8090176

Assari S. Blacks’ Diminished Return of Education Attainment on Subjective Health; Mediating Effect of Income. Brain Sciences. 2018; 8(9):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8090176

Chicago/Turabian StyleAssari, Shervin. 2018. "Blacks’ Diminished Return of Education Attainment on Subjective Health; Mediating Effect of Income" Brain Sciences 8, no. 9: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8090176

APA StyleAssari, S. (2018). Blacks’ Diminished Return of Education Attainment on Subjective Health; Mediating Effect of Income. Brain Sciences, 8(9), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8090176