1. Realizing Children’s Rights in a City

According to the Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, respect for human dignity and equal rights for all people are the foundation of justice [

1]. The rights enshrined in the Declaration include a standard of living adequate for health and well-being, education, work without discrimination, rest and leisure, freedom of opinion and expression, peaceful assembly, participation in the cultural life of communities, and opportunities to take part in government. It follows that a just city seeks to enable its inhabitants to realize their rights. This article describes an effort by one city, Boulder, Colorado, USA, to ensure that the rights of its youngest citizens—children and youth under the age of 18—include participation in municipal government through processes of urban planning and design, regardless of their age, ethnicity or family income.

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights extends to children, after it was ratified in 1948 some child advocates were concerned that children were not adequately protected, given their dependency and special needs [

2]. By 1989, their efforts and related rights-based advocacy resulted in the drafting and adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) [

3]. It consists of 54 articles that require governments to provide for children’s needs, protect them from abuse and exploitation, and guarantee their participation in civil society. Whereas many governments had already accepted responsibility to protect children’s welfare and provide for basic needs like health care and education, the articles related to participation were a radical addition. Except for the right to vote, they extend civil rights to all young people under age 18, including rights to express their views in all matters that affect them, freedom of association and peaceful assembly, freedom of thought and expression, access to information, and participation in the cultural life of their communities [

3].

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the CRC leave it to governments and their citizens to grapple with questions about how to realize rights in a broad range of contexts. These questions include: What are the implications of these rights for the design and construction of cities and public places? How can processes of municipal decision-making accommodate the rights of children? How can they enable all children to realize their rights in the city, regardless of family income, religion, race, caste or ethnicity?

Two United Nations agencies have addressed these questions through programs that form separate but interdependent initiatives. The Growing Up in Cities program of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) arose out of the environmental movement in the 1970s. UNESCO invited urban designer Kevin Lynch to a symposium in Helsinki in 1970 to discuss “the creation of favorable social relationships in a human environment, the prevention of alienation and attention to social and mental health on a community scale” ([

4], p. 22). Eager to learn how people’s relationships to their cities develop from childhood, Lynch proposed a program that would engage young people under 18 in evaluating their urban neighborhoods and public places with the goal of influencing cities to become more responsive to young people’s needs. Although the CRC had not yet been written and, therefore, his efforts were not officially grounded in its principles, Lynch intended to involve young people in participatory processes of planning and design. In the eight cities where the program was originally implemented, no government showed any interest in the outcomes. Frustrated, Lynch [

5] published the methods that he and his city teams pioneered, and the ideas that young people expressed, and went on to other pursuits.

With the adoption of the CRC by the U.N. General Assembly in 1989 and its subsequent ratification by 193 countries, conditions for young people’s participation in urban governance began to change. The new conditions were evident in preparations for the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements in Istanbul in 1996, when UN-Habitat and UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund) jointly organized a workshop that laid the groundwork for a Child Friendly Cities Initiative that provides guidelines for how cities can integrate a rights-based perspective into all services and decision-making processes that impact children [

6,

7]. The initiative grew out of UNICEF’s tradition of urban basic services to protect children from harm and meet their essential needs, but it recognized rights to participation as well [

8]. At the same time, UNESCO revived Growing Up in Cities, which was now also grounded in the CRC. In preparation for the Conference on Human Settlements in 1996, Growing Up in Cities and the Child Friendly Cities Initiative developed with attention to each other, and leaders of one program served as advisors to the other. Reflecting this activity, the Habitat Agenda [

9], which came out of the conference recognizes the special needs of children and youth and advocates participatory approaches and intergenerational interests.

Although the United States, Somalia and South Sudan are the only member states of the United Nations that have not ratified the CRC, the United States is a signatory to the Habitat Agenda, and its cities may independently choose to implement the principles of the CRC. In Boulder, Colorado, an important means to accomplish this goal is the Growing Up Boulder program (GUB), which joins the participatory approaches of Growing Up in Cities with the rights-based focus of the Child Friendly Cities Initiative in order to integrate the perspectives of children and youth into urban planning and design. The program began in 2009 as a partnership between the Children, Youth and Environments Center for Community Engagement at the University of Colorado, the City of Boulder, Boulder Valley School District and several community organizations that work with children [

10]. Four years later, the program continues, building on deepening relationships of experience and trust among its partners.

GUB reaches out to children and youth from all backgrounds, but from the beginning it has been committed to including young people from low-income and immigrant families and ethnic minorities: groups typically marginalized in processes of civic engagement in urban government. They are not often seen and heard at public meetings or represented among city staff. This article describes approaches and methods used to engage with these young people, include their voices in urban planning and design, and communicate to them that they are citizens of the city too, and program partners value their contributions. Some methods and approaches have worked better than others, balancing costs and benefits in the context of limited resources. Therefore, this account includes a history of lessons learned as the program has sought to make the participation of young citizens part of the culture of Boulder’s city government and other local institutions.

2. Boulder as a Microcosm of Inequity

GUB reflects many of the progressive ideals that residents of Boulder espouse. Indeed, the idea that Boulder could be a model city of good practice for youth engagement was a driving force for the program’s formation. Some within and outside the city assume that Boulder is an affluent, predominantly white city that has no need for special initiatives to increase inclusion. The reality is that in many ways Boulder is a microcosm of inequities found throughout the United States, and as a result, not everyone’s voice is heard or represented equally. In fact, the 2011 Boulder Trends Report leads with the question, “Diverse, yes, but are we inclusive?” [

11]. It highlights that while the county as a whole is becoming more ethnically diverse, Latino residents are more likely to experience economic disadvantage, and there is a lack of diversity in public participation and leadership. Less than 1% of local leadership is ethnically or racially diverse, and only 3% of local “creative class” leaders in innovation are Latino [

11].

The City of Boulder is the largest of four incorporated cities in Boulder County, and the county seat. In 2011, 24% of the county’s population identified as a non-white ethnic or racial group, and 14% identified as Latino. Seventeen percent of families spoke a language other than English in the home (

Table 1) [

12]. In the city itself there is less diversity (12% non-white, 7% Latino) and fewer families speak a language other than English at home, with approximately half of these families speaking Spanish (

Table 1). However, while diversity is lower in the city limits, a higher proportion of children under 18 live in poverty in the city (17%) than in the county (13%) (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Boulder as compared to the United States [

12].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Boulder as compared to the United States [12].

| Demographic Category | City of Boulder | County of Boulder | United States |

|---|

| Racial/Ethnic Makeup | 91% White | 87% White | 74% White |

| 7% Latino | 14% Latino (any race) | 17% Latino |

| 4% Asian | 4% Asian | 5% Asian |

| 0.7% African American | 1% African American | 13% African American |

| 0.1% Native American | 0.4% Native American | 8% Native American |

| 8% Other, Two, or More Races | 8% Other, Two, or More Races | 11% Other, Two, or More Races |

| Language Other than English Spoken at Home | 12% | 17% | 21% |

| Children in Poverty | 17% | 13% | 22.5% |

| High School Graduates | 95% | 94% | 86% |

Although Boulder is less diverse than the United States as a whole (

Table 1), racial and ethnic inequalities still exist, with many more Latino children affected by poverty than children in any other group [

11]. In the Boulder Valley School District, Latino students, students with limited English proficiency, and those from economically disadvantaged households are more likely to drop-out of school [

11]. Though the overall graduation rate is higher than the national average, only 48% of Latino males in the district graduated from high school in 2010. This compares to a graduation rate of 95% for the district as a whole (

Table 1) [

11].

These numbers do not completely reflect the growing population of undocumented families residing in the community. Many undocumented youth in Boulder, as elsewhere, have spent much of their lives trying to be invisible. While GUB staff and leadership believe that all youth have a right to participate in decisions that shape their city, they feel a special commitment to include youth who are least likely to be heard, due to immigration status, ethnicity, income, or language barriers. For first generation children who might not have grown up in a culture of participation or know how to work within U.S. political and social systems, GUB may be their first opportunity to express their voice in public in a meaningful way. GUB and its partners protect young people’s identity by using only first names and allowing students to opt out of pictures or events where appropriate; to date, GUB has not experienced or known of youth who have been fearful of participating in any activities because of immigration status. In fact, for the majority, participation has enabled these youth not only to speak out about civic issues, but to express their desires about their lives in general.

3. Developing an Organizational Structure for Inclusion

GUB began when members of the Children, Youth and Environments Center at the University of Colorado approached the director of Community Planning and Sustainability for the City of Boulder about introducing principles of Child and Youth Friendly Cities and methods of Growing Up in Cities into city planning and design. He enthusiastically endorsed the idea, with the encouragement of the several city council members and the mayor. Knowing the importance of school district collaboration in order to reach young people in a sustained way, the Boulder Valley School District (BVSD) was invited to sign on as another major partner. The partnership of these three groups was formalized through a Memorandum of Understanding, and representatives of each group serve on GUB’s Executive Committee. To build a broad-based alliance, interested private schools and out-of-school organizations were also invited to participate. The city’s Department of Children, Youth and Family Services and Department of Parks and Recreation have also played a role. Representatives of this larger partnership form the program’s Steering Committee, which meets every other month to review the progress of current projects and plan new initiatives.

The Children, Youth and Environments Center (CYE), which is based in the Environmental Design Program at the University of Colorado, brings important resources. It attracts faculty and doctoral students who are interested in how cities serve young people, young people’s perspectives, and participatory planning and design. They create classes which engage undergraduate design and planning students in participatory processes with high school, middle school and elementary school students, and two doctoral students have completed dissertations on topics related to GUB. The CYE Center also offers regular undergraduate internships, which enable design and planning students—some of them young people of color themselves—to play lead roles in particular program initiatives. Several architects who came to the Center as Visiting Scholars have also contributed to projects. Not least, the Visual Resources Center in the Environmental Design Program documents all stages of GUB’s work.

GUB could not operate without at least one part-time paid coordinator. For most of GUB’s duration, there have been two part-time coordinators who are responsible for day-to-day operations including project management and intern supervision and who convene the Executive Committee and Steering Committee to review achievements, discuss lessons learned, and strategize new directions. These positions are currently funded by the city’s Department of Community Planning and Sustainability, with funding in the past coming from the university through direct grants and course buy-outs, BVSD, the CYE Center, and a private donor. The coordinators work in the CYE Center, which enables them to communicate easily with faculty, doctoral students, visiting scholars, undergraduate classes and interns.

4. Finding Effective Methods

GUB has built on many of the original methods employed by Growing Up in Cities, including community assessments, mapping, model building, photogrids, photo documentation, interviewing, participatory action research, and presentations to city representatives [

13]. It has added digital storytelling [

14] and the City as Play approach for creating interactive planning models [

15,

16]. Its method of sending children out to take photos of their environment and write brief commentaries about their lives and the places they select, which GUB adopted from Growing Up in Cities, has been promoted by Wang and Burris [

17,

18] as photovoice. Different methods have been chosen for different projects.

Youth have most eagerly engaged with methods that facilitate expression and discovery, such as photography, art and field trips. They have sometimes resisted more conventional methods of participation, such as attending public meetings, interviewing and writing, which can be alienating forms of communication for English language learners. Student participation in city council meetings has been a powerful form of participation, yet one of the most difficult to implement. In chronological order, the following sections describe some of the projects that GUB has initiated, methods employed, and lessons learned about how to involve young people from under-represented communities most effectively.

4.1. Action Groups

GUB began with a Youth Steering Committee composed of middle school and high school students who were recommended by their school principals. Principals recommended students with leadership skills, including both students who excelled in school as well as others who were not necessarily top students but who might be interested and benefit from an opportunity to participate in the initiative. They helped organize a kick-off event, which brought together approximately 75 youth who expressed their interests and concerns related to the city. One outcome of this event was the identification of three topics for action: youth-friendly businesses, public art, and nightlife. Youth wanted to have a visible presence in the city through art, to be treated by businesses with the same courtesy given to adult customers and to have access to part-time jobs, and to find affordable and safe nightlife opportunities in a city dominated by university students, tourists and high-income adults.

Each action group was implemented differently. The Art Action Group involved schools and out-of-school programs, including the I Have a Dream Foundation (IHAD) and Manhattan Middle School. IHAD is a nationwide program whose mission is to empower youth from low-income families to reach educational and career goals. It provides educational tutoring, mentoring, cultural enrichment through school-based and after-school programs, and financial support for college. Manhattan Middle School is a public school with an arts focus. Youth began by talking about what they liked and did not like about the city of Boulder and then painted all-weather banners of their vision of a child and youth friendly city. IHAD youth worked with an artist who helped them articulate their ideas and asked them to draw pictures. The artist then compiled their ideas and drawings into a single banner, which the youth painted (

Figure 1). Youth were surprised and excited by this project because no one had ever asked them questions about their community before. It gave them an opportunity to reflect about their community and themselves and see that people valued their culture and ideas. The murals hung in the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, the Boulder Creek Festival, and several GUB events.

Figure 1.

“Dreamers” and the facilitating artist painting a banner in the after school program at Manhattan Middle School (photo courtesy of GUB).

Figure 1.

“Dreamers” and the facilitating artist painting a banner in the after school program at Manhattan Middle School (photo courtesy of GUB).

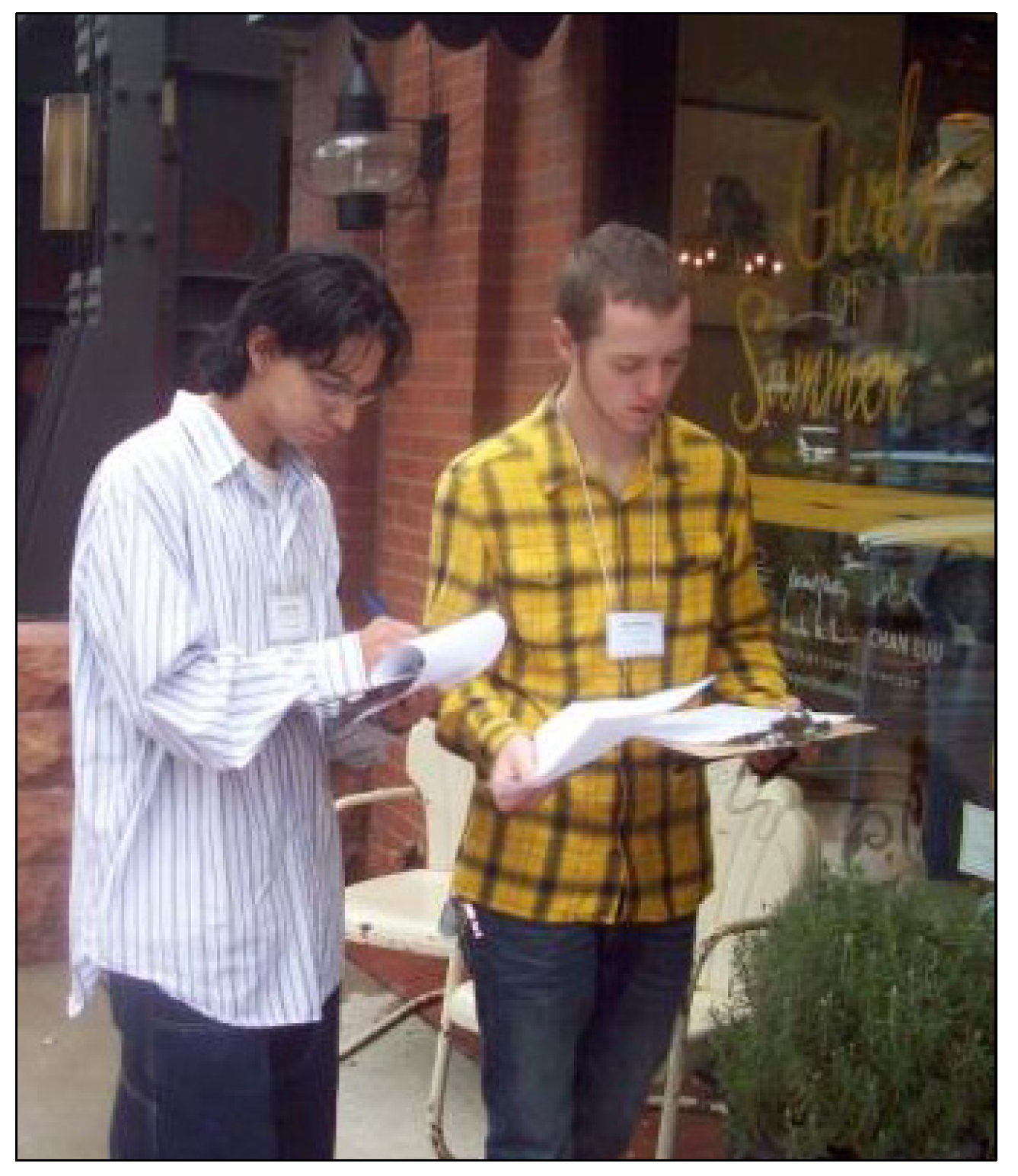

The Business Action Group involved the most intensive adult contributions. The Director of the CYE Center and GUB staff met with a small but dedicated group of high school students to train them in research. The students had backgrounds of both privilege and disadvantage and were all interested in encouraging local businesses to be more youth-friendly. The group initially met every Saturday for several months and developed an interview protocol to determine if downtown businesses hired minors and if they had any special rules for youth in their establishments (

Figure 2). They piloted this process and developed a short video to summarize their findings. For the most part, business owners and managers were receptive to the students and answered their questions respectfully. Yet, the owner of one relatively busy coffee shop asked them to leave without answering any of their questions or acknowledging their efforts to improve the treatment of youth in downtown businesses. Although this bothered them, they were mostly undeterred and continued with their efforts. The students spoke and showed the video at school assemblies and a GUB event, talked with city councilors, and found themselves written up on the front page of the city’s daily newspaper. To move their work forward, the owner of a downtown business also mentored them as they developed criteria for child-friendly businesses, started a database of local jobs for teens, and prompted Downtown Boulder, Inc. to restart a dormant internship for high school students. The group met regularly for over a year until many of the students graduated or moved on to other interests. A member of the action group stated that prior to GUB he had represented youth as part of a municipal youth leadership program, but in contrast “(GUB allowed) youth to have direct input, which is what I really enjoyed”.

Figure 2.

Business Action Group collecting data on youth-friendly businesses (photo courtesy of Growing Up Boulder (GUB)).

Figure 2.

Business Action Group collecting data on youth-friendly businesses (photo courtesy of Growing Up Boulder (GUB)).

The Nightlife Action Group was the most challenging to implement due to inconsistent youth participation in the group. GUB worked with the YMCA Teen Advisory Board and a few other high school students who were invested in this issue. The YMCA group was happy to consult on this issue but not ready to commit to extended research. The independent high school students met several times to design, administer and analyze the results of a survey of existing and desired nightlife opportunities, how much students could spend on events, how they want to find out about activities, and the modes of transportation they use in their daily lives. More than 500 Boulder high school students completed the survey, which resulted in a report that garnered the attention of city council members, led to the development of monthly teen nightlife activities at the YMCA, and led a computer programming class at the local vocational high school to develop a prototype of an information portal for teen activities and topics.

A core member of the Business Action Group was a Native American student, and art activities with IHAD and Manhattan Middle School involved many students from low-income and ethnically diverse families. Typically, however, youth from marginalized populations did not volunteer for leadership in these action groups. Common reasons were that their time was allocated to other responsibilities, such as sibling care or after-school jobs, and they lacked reliable means of communication. Many action group meetings were held on the university campus, which was difficult for youth from these families to reach. In addition, their peer groups or parents did not always promote GUB activities. Experience with these three action groups underscored the importance of working with established partners in youth-serving organizations, who engage with young people where they live or attend school and who have already built bonds of trust. While trust is important in any adult-youth relationship, it is even more important in sustaining participation with youth from marginalized populations.

Building on this experience, GUB staff worked with a teacher to initiate a Teen Mothers Action Group in the spring of 2010 with a group of teenage mothers who attended Fairview High School in Boulder. The young women ranged in age from 13 to 19 years, with their children’s ages ranging from 0 to 3 years. GUB staff worked with them in their classrooms to identify what they liked about living in Boulder and what they wished to change. One of their most common requests was to modify the city’s housing program. Under existing policies, only those 18 or older could apply for public housing. In addition, applicants could be waitlisted for up to 3 years. This posed a challenge for teen families who wished to live independently but could not afford it. Teen mothers expressed concern about becoming homeless.

While teen mothers have parental responsibilities, they are still teenagers at heart, and share many of the interests, concerns, and desires of their peers, including underage nightlife and safe and inclusive places to hang out, such as shopping malls and parks. While Boulder has commercial centers and many parks, they are not always accessible without a car and most are outside, which means they get limited use in winter. The teen mothers expressed their ideas in letters to the city council, and GUB staff summarized their concerns and set a date for them to speak to council members. GUB provided support, from pizza to child care, to enable them to attend the council meeting. However, not a single young mother showed up.

GUB staff then arranged to have two city councilwomen come to the teen parenting program at their school. About 20 students shared their suggestions for how to make Boulder a better city for both young children and teenagers, and the councilwomen engaged in a meaningful dialogue with them. They gave information about opportunities for free entertainment, plans for affordable stores, and existing low-cost, drop-in child care services. They shared that a taskforce had been created around the issue of affordable housing and asked the young women about housing amenities they would like. The councilwomen worked some of the teen mothers’ ideas into existing initiatives, and still talk about this exchange two years later. Despite GUB staff preparing teen moms for the city council meeting, in the end, these young women were not comfortable with or interested in participating in a more formal and adult-driven process. This project speaks to the importance of engaging youth in places where they already gather, through dialogue that generates social learning and meaningful participation [

19].

4.2. Digital Storytelling

Digital Storytelling provides an opportunity for participants to create digital media, using still photos, a recorded narrative and music, to inform the public about critical issues from a personal perspective. With its roots in community arts and oral history, it allows community members to tell their own stories [

14]. Prior to the establishment of GUB, instructors associated with CYE taught a university course that incorporated digital storytelling and principles of participatory community planning into the curriculum. Through this course, the instructors developed partnerships with several groups of high-school students, including the teen mothers group at Fairview High School, and multiple classes at Arapahoe Ridge High School, a technical school which enrolls many students from both low-income and ethnically diverse populations in Boulder County. At the culmination of each semester, some of the high-school students presented their digital stories to City Council. As a follow-up to this work, GUB staff approached a teacher at Arapahoe Ridge High School in the fall of 2010 about facilitating a digital storytelling project focused on youth ideas for community change. This teacher had participated in the earlier digital storytelling workshops and knew the process of producing the short videos [

20].

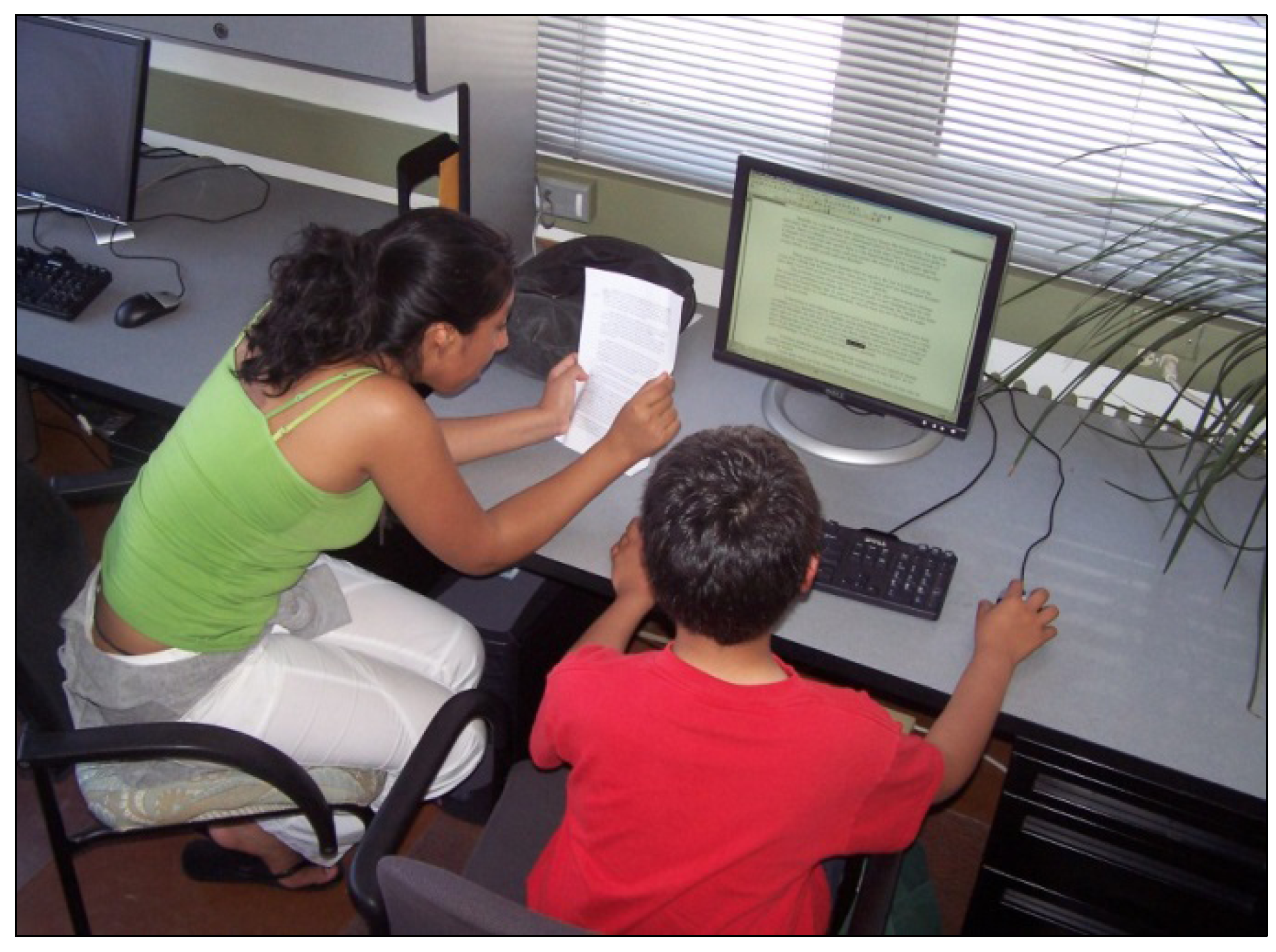

GUB staff began by asking the students to identify community issues that they wanted to resolve and lent them cameras to take photos around their community. With the teacher’s help, each student generated a story idea, wrote a narrative, chose photos and non-copyrighted music, and combined it all into a short video (

Figure 3). Once the digital stories were created, GUB staff organized a screening session for the Boulder City Council. Although a benefit of digital storytelling is that videos can communicate a message without the creator being present, GUB staff wanted the stories to lead to deeper discussions around community issues between the youth and City Council. Unfortunately, only a few students showed up for the screening, and when some council members asked hard follow-up questions, youth interpreted it as challenging their work rather than showing support. Although GUB staff did not officially follow-up with the students to determine why so few of them attended the presentation, we suspect that an evening presentation on a school night was not convenient for most of them. The city council meetings are held in downtown Boulder, so for students who live on the outskirts of the city or in a different community altogether, transportation to and from the event may have been difficult. In addition, for students such as the teen parents, the need for childcare also adds to the difficulties of trying to attend an evening meeting.

Figure 3.

A Children, Youth and Environments Center (CYE) intern and a Boulder youth developing the narrative for a digital story at the CYE Center (photo courtesy of Debra Flanders-Cushing).

Figure 3.

A Children, Youth and Environments Center (CYE) intern and a Boulder youth developing the narrative for a digital story at the CYE Center (photo courtesy of Debra Flanders-Cushing).

GUB also worked with an AVID class at Boulder High School where 10th graders created digital stories to describe what they wanted for their communities. AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination) is a nationwide program to prepare students for higher education. The program works in schools, focusing on the “least served students in the academic middle” [

21]. Many students in the AVID class were surprised to learn that their city, the local university and others cared about their opinions. One student, an English language learner from Russia, described his desire for a BMX bike park in Boulder that would help teens stay out of trouble and engage in pro-social activities. Two years later, he reflected that creating a digital story was the most impactful project of his education because he learned that his voice mattered.

4.3. Child and Youth Bill of Rights

An AVID teacher who volunteered for the digital storytelling workshops at Boulder High School was intrigued by GUB’s methods of engagement, and she became an ongoing partner who has involved her students in several GUB initiatives, including exploring a Child and Youth Bill of Rights for Boulder. The AVID curriculum has community service built into it, which has been critical in sustaining this partnership beyond a single outreach project. AVID was one of four classes that GUB engaged in a curriculum about child and youth rights, but the only one primarily composed of students from low-income and minority families. Students studied what a Youth Bill of Rights is and examples of what it looks like in other places, and developed suggestions for what they would want to see in a Youth Bill of Rights for Boulder. AVID youth were very active at a large GUB event, which showcased student work about child and youth rights (

Figure 4).

In addition, as part of the curriculum, GUB asked a Latina law professor and Latina law student from the University of Colorado to speak to the AVID class about youth rights. The visit was an inspiration to many students, who commented that their stereotypes of lawyers were shattered by these two women.

Figure 4.

Two Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) students talking with two other high school students about a youth bill of rights at the GUB annual event (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 4.

Two Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) students talking with two other high school students about a youth bill of rights at the GUB annual event (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

Some said they could now consider law for a profession. In a follow-up letter, one student wrote, “I feel as if you really inspired me to try to do my best and to prove to people that although I am Mexican, I can achieve it if I put my mind to it”. Another said, “I loved that you take pride in your work and that you’re a fellow Latino and that you are making a name for us”. This experience emphasized the importance of exposing youth to ideas and professions through role models that are ethnically similar to the students involved.

4.4. Civic Area Planning

During the summer of 2012, GUB began working with youth to assess and make recommendations for a major redevelopment of Boulder’s Civic Area, a downtown district that includes the main public library, the municipal building, the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art (BMoCA), the Boulder Creek greenway, a central park, and an area used for the farmers’ market. GUB worked with socio-economically and ethnically diverse populations through the IHAD “Dreamers”, the AVID class at Boulder High School, a civics class at New Vista High School, and a Casey Middle School leadership class. GUB staff began outreach by seeking out families at the farmers’ market, but because they did not find much diversity there, they moved to a park along the creek where many ethnically and socio-economically diverse families spend Sunday afternoons. They interviewed family members there about what would make the Civic Area a more inviting and inclusive place. They then engaged Dreamers from the IHAD program in a series of photovoice sessions, in which young people framed and photographed Civics Area spaces that they liked (framed with green,

Figure 5) and disliked (framed with red,

Figure 6) [

13]. The photos were displayed at a public meeting at BMoCA that launched the Civic Area public participation process (

Figure 7) and later hung in a popular frozen yogurt shop near Boulder High School. At the public meeting at BMoCA, youth were given a designated display space, but this space was re-assigned 3 times at the beginning of the meeting. Not only did this frustrate both youth and adults, but it devalued youth work. Once established in their final location, many adults from city departments as well as the community at large did engage in genuine dialogue and showed real interest in the work. This helped diffuse feelings of frustration and allowed the Dreamers to end the evening with a feeling of success.

Figure 5.

A “Dreamer” using photovoice to document positive public spaces in Boulder (photo courtesy of Brendan Hurley).

Figure 5.

A “Dreamer” using photovoice to document positive public spaces in Boulder (photo courtesy of Brendan Hurley).

Figure 6.

Students highlight their discomfort with Boulder’s homeless population in the Civic Area (photo courtesy of GUB).

Figure 6.

Students highlight their discomfort with Boulder’s homeless population in the Civic Area (photo courtesy of GUB).

Figure 7.

A “Dreamer” presenting results of the photovoice project at a public meeting for the Civic Area (photo courtesy of Stephen Cardinale).

Figure 7.

A “Dreamer” presenting results of the photovoice project at a public meeting for the Civic Area (photo courtesy of Stephen Cardinale).

In the fall, GUB staff, graduate students, and undergraduates from the university’s environmental design program supported the public school classes over a period of three months in making field trips to the Civic Area, creating photogrids that involved taking photos at regular intervals, interviewing family members about great public spaces, meeting with city councilors and urban designers, and consolidating their ideas into Power Points and presentation boards that they shared with each other and the public (

Figure 6). Many parents and families of AVID students attended the city’s final visioning meeting for the Civic Area (

Figure 8). Graduate students in design created three-dimensional renderings that integrated youth ideas into existing spaces in the Civic Area (

Figure 9).

Figure 8.

AVID students and parents celebrate their contributions to the Boulder Civic Area (photo courtesy Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 8.

AVID students and parents celebrate their contributions to the Boulder Civic Area (photo courtesy Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 9.

Rendering of student ideas for making the Civic Area more child- and youth-friendly. The green space currently exists, but the play structures do not (image courtesy of Ilaria Fiorini and Pier Luigi Forte).

Figure 9.

Rendering of student ideas for making the Civic Area more child- and youth-friendly. The green space currently exists, but the play structures do not (image courtesy of Ilaria Fiorini and Pier Luigi Forte).

At the end of the term, students evaluated their participation using a plus/delta technique which asked them to say what they liked (plus) and what they would change (delta). Students liked the photogrid method and field trips. Some liked presenting to city council, but overall, they did not like the public meetings or interviewing family members. They enjoyed interacting with the undergraduate interns, and they were inspired by a presentation on great public spaces by an architect and urban designer. They used many of the design elements in his presentation in their own suggestions for the Civic Area. Though it was not listed as a positive event by many, the process of presenting to city council was a powerful experience for the two young women who did it. In an essay reflecting on her experience, one AVID student stated:

I really enjoyed doing this project because it was a new experience for me. I got to work with my peers. We went on field trips. I got over my biggest fear which was talking to a big crowd of people, to the mayor, I was even live on t.v.! When I’m applying to colleges it will look good on my application. I am so excited to do another project like the civic area. I’m so glad I did it. Don’t get me wrong. At first I was a little unhappy because I didn’t know what to expect. I’m glad that in the end everything came out great.

In other writings, the same student conveyed her desire for a place where all people would be respected: “a safe and welcoming place for everyone of all ages”. Her reflection suggests the importance of sometimes pushing students beyond their comfort zone if they are adequately supported. Neither of the two students who volunteered to speak to the city council as representatives of their classes had any conception about government functions, and neither had been to a city building before. They were excited that they would be on television during the council session but when they arrived, they were intimidated by the number of councilors sitting in front of them. A GUB coordinator told them, “You do not have to do this, but I think you have important things to say and we will all miss out if you do not share your opinions”. She reassured them that she would do whatever they wanted for support, but ultimately it was the youth who chose to speak, and they did it well. The GUB coordinator had prepared the councilors via email that these youth would be coming, and the councilors were welcoming because they knew the students needed encouragement.

The two youth who voluntarily presented their ideas to City Council found the experience to be highly positive; however, the majority of their peers chose not to participate in this part of the process. They preferred the photogrid method to express their ideas. While no youth specifically explained their hesitance to participate in the formal process, GUB staff sensed that this was due to individual shyness, logistical concerns of participating after school, and a lack of the “coolness factor” in talking to city officials. It is also possible that sometimes it is enough for youth to have the experience of sharing their thoughts and voice with their peers. While adult attention to youth ideas is obviously significant, the process of expressing their views can be empowering in and of itself.

GUB introduced a new method of engagement, called “City as Play”, to the Casey Middle School leadership class. Pioneered by James Rojas with the Latino Urban Forum in Los Angeles [

15,

16], it enables participants to place found objects on an aerial map of the space to be reimagined. Rojas found this use of playful and familiar everyday objects to be more accessible than more traditional planning methods. It was a creative means to engage the students in problem solving. Students addressed the need for flood mitigation in the Civic Area with underground cisterns modeled from a baby chew toy (

Figure 10) and introduced interactive climbing structures and a “parade of animals” outdoor sculpture made from animal-shaped plastic beads (

Figure 11). They then worked with GUB staff and an Environmental Design student to build a computer generated Sketch-Up model of the area, which was presented at a final public meeting for the Civic Area visioning process.

Figure 10.

One of Casey Middle School students’ “City as Play” models for the Boulder Civic Area (image courtesy of Katherine Buckley).

Figure 10.

One of Casey Middle School students’ “City as Play” models for the Boulder Civic Area (image courtesy of Katherine Buckley).

Figure 11.

Casey Middle School students showing their “City as Play” method with animal sculpture (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 11.

Casey Middle School students showing their “City as Play” method with animal sculpture (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

4.5. Exploring Homelessness

When youth evaluated the Civic Area, they repeatedly expressed concerns about the homeless who frequent this space (

Figure 6). They struggled over how to talk about the homeless, both in terms of the actual terminology in referring to them and also the reasons for homelessness. As a result, AVID classes decided to develop a curriculum on homelessness in the winter of 2013.

Speakers from the Boulder Shelter for the Homeless and the Bridge House, a day program for the homeless, visited 9th and 10th grade AVID classes and shared their own stories and others’ stories of homelessness. Students read The Glass Castle: A Memoir by Jeannette Walls, and a subset of students volunteered at either the shelter or Bridge House kitchen. Youth were able to take their negative and inarticulate feelings about homelessness and turn them into an opportunity to delve into this topic, understand homeless people’s life histories and vulnerabilities, and contribute to their support.

4.6. Creating a Photovoice Exhibit

Piloting photo methods with IHAD Dreamers as part of the Civic Area assessment led to a different application of the photovoice method. Youth Services Initiative (YSI) is an after-school program of the City of Boulder Parks and Recreation Department, serving predominantly Latino youth from public housing and low income neighborhoods. The YSI coordinator heard about the Civic Area outreach with Dreamers and expressed a concern that many of the youth she works with might not be interested in a relatively abstract planning project when they are worried about family safety, hunger, and deportation. As a result, YSI and GUB launched the Neighborhood Photovoice project to enable youth to use photography to document their neighborhoods and issues they face but sometimes find difficult to articulate, with the goal of mounting a public exhibit.

This project simultaneously addressed an interest in photography expressed by many YSI youth, provided training in photography and literacy, developed participants’ sense of civic responsibility and voice, and educated other people in Boulder about the diversity of issues its young residents experience. It brought together a photographer who had recently returned from Peace Corps service in Costa Rica, where she used photovoice with teen girls, a GUB intern with a Latino background, and YSI youth who met on a weekly or bi-weekly basis through the winter and spring of 2013 (

Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Youth Services Initiative (YSI) photovoice facilitators, a professional photographer and GUB undergraduate intern from the Program in Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, posing with youth photos (photo courtesy Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 12.

Youth Services Initiative (YSI) photovoice facilitators, a professional photographer and GUB undergraduate intern from the Program in Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, posing with youth photos (photo courtesy Lynn M. Lickteig).

Many youth had never used a camera before, and many were hesitant to photograph their homes, saying it was boring or there was nothing to show. YSI staff believed that at the beginning, many youth felt ashamed and did not realize that other youth lived as they did, or that the project could be an opportunity to say what they wanted to change in their lives. As they worked, they began to express their dreams, including career aspirations and their desire to go to college, to eliminate poverty, and to have greater agency over their lives. They shared the importance of family, friends, and connections to home in both the United States and Mexico.

Their photographs and ideas were displayed in a month-long exhibit at the North Boulder Recreation Center, where YSI youth meet. The Recreation Center receives approximately 1500 visitors a day, so it is a place of high visibility that can expose many of Boulder’s more affluent residents to issues that some of Boulder’s youth experience. Initially, youth were hesitant about expressing themselves, but when the project facilitators brought images together for a photo critique, they began to see themselves as artists with something to say. Through a series of prompts, they were able to develop a voice that was powerful and meaningful. At the opening event, many shared a sense of pride not just in their images, but also in themselves (

Figure 13). By coincidence, one youth had been a participant in the IHAD and YSI photovoice projects and in the Civic Area curriculum. At the photovoice opening, GUB staff noticed that she expressed a new level of confidence and pride. The exhibit prompted feedback from city staff and local teachers to YSI staff and youth themselves about how impressed they were with the quality and content of the project.

Figure 13.

A YSI youth sharing her photographs with a visitor to the neighborhood photovoice opening (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

Figure 13.

A YSI youth sharing her photographs with a visitor to the neighborhood photovoice opening (photo courtesy of Lynn M. Lickteig).

5. Discussion of Lessons Learned

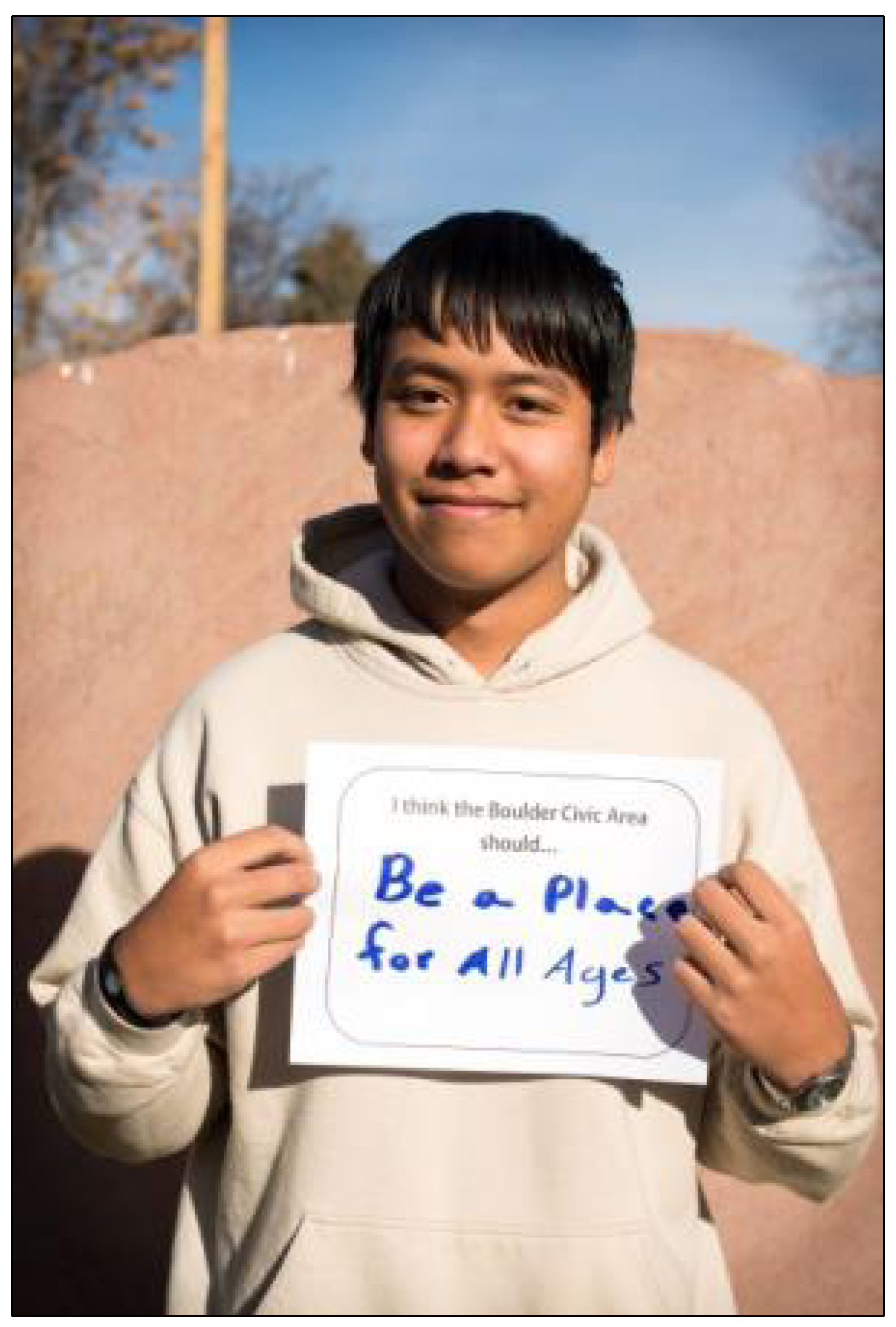

Since GUB was established in 2009, its staff and partners have learned much about youth engagement. Through the many projects undertaken and the many methods introduced, partners have been able to share incremental learning. Many of the lessons apply to youth in general, but can be especially significant when working with youth from marginalized populations. The biggest lesson is that engagement needs to be on youths’ terms, with methods that they find exciting and relevant. While this may seem obvious, it can be challenging to implement consistently. The City of Boulder is a key GUB partner, and city council members and planning staff want to hear youth perspectives on predetermined issues related to planning and urban design. For youth, the timing and topic of these issues may not always seem relevant. The challenge is to find ways to balance city interests with methods and approaches that intersect with youths’ lives. The Civic Area is a good example. At first, youth felt little connection to this area. It is currently not a place where they spend much time, in part because of the noticeable homeless population there but also because they do not find much to do there. Youth repeatedly expressed a desire for more places to hang out, both indoors and out. This desire was expressed by the Action Groups, the teen mothers, and in a variety of forms since. The Civic Area provided a perfect opportunity to not only assess existing conditions within Boulder, but also to begin to imagine a different world, one that would be welcoming to people of all ages and cultures (

Figure 14). When youth were invited to reimagine this area in this way, they became engaged.

Figure 14.

An AVID student with his vision for the Boulder Civic Area to “be a place for all ages” (photo courtesy Stephen Cardinale).

Figure 14.

An AVID student with his vision for the Boulder Civic Area to “be a place for all ages” (photo courtesy Stephen Cardinale).

Another lesson learned is that even minimizing barriers to participation does not ensure that youth will show up. The most effective way of engaging youth is to go where they are, whether it is in a classroom or out-of-school program. This not only creates a comfortable setting for youth, but allows for broader and more consistent participation. It conveys a message that city leaders care and are listening, more than when they require youth to attend a council meeting and present their ideas within the constraints of adult formalities. It shifts participation from an adult-driven agenda to a youth-centered dialogue. Of course it is important for youth to learn how formal government processes work, but creating alternative settings for participation can foster mutual learning between city officials and youth. For youth from marginalized populations, whose lives may be crowded with family obligations and out-of-school work, who may lack convenient transportation, and who may feel intimidated by formal processes, this principle is especially important. In the words of Percy-Smith ([

19], p. 169), “the act of bringing different groups together fosters a sense of collective commitment, accountability, and responsibility”. GUB staff have provided substantial mentoring to participate in formal processes such as city council meetings, but ultimately this method of participation appeals only to a small subsection of youth from all populations. This preference is reinforced by a GUB study that found youth and adults had different perceptions about how youth should participate in civic processes. In short, adults thought youth should participate in formal adult processes, and youth preferred more informal and interactive participation [

22].

The quality of adult response and dialogue has also influenced youth perceptions of the value of their voice. Examples from the Business Action Group and the civic area meeting at BMoCA highlight that adult response can lead to youth frustration at not being taken seriously. However, in the majority of GUB’s projects that involve youth-adult interactions, young people’s ideas have been heard and considered. This is in part because the city is a founding partner of GUB and because GUB’s formation was based on the principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child [

3]. It has also been supported by translation: the methods used to engage GUB youth are different from traditional methods for adult community input, but GUB staff and interns typically translate end-results into adult-friendly formats, such as bullet point lists, presentation boards, or a summary of ideas.

One outcome that is both a challenge and a benefit of the work is that over time city staff have incorporated youth ideas and ideals into the city’s overall goals and needs. This makes it challenging to specifically identify ideas that emerged from GUB programming and youth themselves but also speaks to the notion that youth ideas (and ideas from any marginalized population) should become infused into the overall planning and decision-making process. Good design is universal design and incorporates the needs of a diverse group of citizens. Successful incorporation of youth ideas into an overall planning process can make their individual contributions harder to discern or attribute but no less significant.

GUB staff has also learned that not every partner is a good fit. Even when organizations appear to share common goals, the interests and approaches of their staff may not be aligned. Partnerships work well when everyone’s interests are served. Vital partners include both those who work with youth on a regular basis, such as AVID teachers and the staff at IHAD and YSI, and partners who create settings where youth ideas can be heard and respected, such as the city’s Department of Community Planning and Sustainability. This need for synergistic goals highlights the importance of flexibility. Sometimes GUB adapts its programming to meet emerging needs, such as with the AVID homelessness curriculum or the YSI photovoice project. At other times, GUB seeks out partners interested in a predetermined planning topic, such as the civic area redesign. This places GUB in the middle of the youth leadership spectrum described by Zimmerman [

23], where youth provide regular input and occasionally take substantive leadership roles, but where the focus of activities is determined by adults.

GUB staff have found that not all youth want to take on leadership roles as traditionally defined by adults. Traditional methods of participatory action research expect youth to identify issues of concern to them and engage in research methods such as interviews and surveys. GUB began by introducing this process to the Business Action Group and Nightlife Action Group, but these methods appeal to a smaller sector of youth than processes that cultivate voice through art, digital media and photography. “Whole systems action research”, which involves learning by local officials and organizations along with young participants, can move youth beyond tokenism and into shared learning and dialogue, but its application requires creative methods and broad definitions of participation in order for dialogues to be of mutual benefit and interest [

24,

25]. This broad view values partnership as much as autonomous leadership, which makes it consistent with more collectivist cultures of the Global South [

26]. Given the length of time social change takes, people need to be ready to commit to sustained funding and effort [

27].

GUB staff has begun to follow and interview some of the program’s most active youth to assess impacts. However, until GUB completes more systematic analyses, it is difficult to know the role that GUB plays in shaping young people’s views of themselves as citizens. These benefits can also be difficult for youth to understand and articulate, as in the case of the previously mentioned AVID student who realized two years after participating in the digital story project how it transformed his worldview. Other youth have spoken about overcoming a fear of public speaking, or realizing that people like themselves can attend college and have positive impacts on the world. For youth like those in AVID, IHAD or YSI, who have yet to determine whether to pursue college aspirations, these realizations can be significant. Research has shown that youth ties to community promote social and emotional well-being [

28]. From this perspective, GUB seeks to minimize young people’s feelings of social exclusion by showing that they belong to a larger civic community, and to maximize their sense of self-efficacy and self-determination [

29].

Sutton ([

29], p. 639) suggests that low-income and minority youth experience injustice because they “lack resources, positive recognition as a cultural group, and opportunities to participate as citizens in a democratic society”. GUB seeks to address all three areas of injustice. The Civic Area project, for example, enabled AVID and Casey Middle School youth to talk about resource distribution (by designing spaces that would serve their own needs as well as those of others), identify themselves and other cultural minorities as significant stakeholder in the Civic Area, and participate as citizens through city council meetings, public workshops and dialogues with urban planners. Even though youth did not enjoy all activities equally, their opportunities to participate in this range of activities indicated that council members and city staff were listening and wanted to take their ideas seriously. Most research on youth participation emphasizes the benefits youth gain from participation, rather than the contributions youth make for community betterment and social change (such as through involvement in city planning initiatives or action groups) [

26]. Four years after participation, a member of the Business Action Group reflected that GUB “has made me understand that even youth have a perspective and that we should understand it [and] not just rely on older people to make decisions”. Now a university student, he has been involved in a number of leadership roles, including with the Native American First Voices club. One of GUB’s values has been its ability to provide youth with new experiences and skills while at the same time contributing to the overarching goal that youth share in the development of a city that will be friendly for all ages. Comparable programs have had similar results, with youth both making a positive contribution and developing as individuals through the process [

23,

27,

30,

31].

GUB is founded on principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child [

3], particularly the articles related to civil rights and children’s right to a voice in decisions that affect their lives. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has made it clear that this includes decisions that impact children’s environments [

32]. Equally important to GUB, it can be argued, is Article 29 on education, which stipulates that education shall be directed to “the development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential”, “the development of respect for human rights”, and “the preparation of the child for responsible life in a free society, in the spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, equality of sexes, and friendship among all peoples”. By reaching out to ensure that young people from marginalized groups are well represented in program activities, GUB is dedicated to promoting their personal development as well as their visibility and standing in the city. GUB staff has deliberately raised young people’s awareness about children’s rights by explaining project goals and introducing the initiative to write a Child and Youth Bill of Rights for the city.

GUB staff and Steering Committee members never anticipated that participants would bring GUB full circle. When AVID classes undertook to create a curriculum on homelessness, in response to young people’s fears of the homeless in the Civic Area, this is what happened. The curriculum engages students in reflecting on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [

1], from which the Convention on the Rights of the Child springs. It also pursues an original UNESCO goal for the Growing Up in Cities program, from which many GUB methods are derived: “the prevention of alienation and attention to social and mental health on a community scale” [

4]. Efforts to increase young people’s awareness of their own rights led them to an investigation of issues of human rights and social justice on a community-wide scale, and this is as it should be.