White Women Wanted? An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Social Justice Magazines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

For example, a demographic measure of One Green Planet contributors indicates that 90% of the 137 featured authors present as white. 5 Likewise, of 67 Animal Rights Zone podcast guests, 93% appear to be white-identified. 6 Indeed, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement might be said to abide by post-racial epistemologies that, as Harper [3,4] suggests, are insufficient in recognizing the very real consequences of socially created racial ascriptions: “My critique is that there are those (white and non-white) who believe ‘race is a feeble matter’ in animal rights activism. Such people are producing and practicing their own ‘post-racial’ epistemologies and praxis of AR/VEG ‘cruelty free ethics’” [3] (p. 17). Adding to this, Adams [22], Gaarder [24], and Wrenn [29] have suggested that the movement also exploits gender inequality in an effort to advance Nonhuman Animal rights.Popular vegan-oriented literature in the USA […] [does] not deeply engage in critical analysis of how race (racialization, whiteness, racism, anti-racism) influences how and why one writes about, teaches, and engages in vegan praxis and ultimately produces vegan spaces to affect cultural change (p. 8).

Though class is not specifically explored in this study, it is a variable that very often intersects with gender, race, and body size. Implicit class representations in social movement media may also work to prevent strategic alliances among left-leaning movements. For these reasons, inequality in movement-produced material is incompatible with social justice goals and is also detrimental to necessary coalition-building.Though VegNews surely has its largely upscale market and audience in mind, the magazine does little to effectively counter the prevailing notion of veganism as the exclusive practice of upper-class, new-agey “bourgies”, and it does little to promote solidarity or affinity based anything beyond buying cool “green” stuff [30] (p. 136). 7

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Profile of Samples

3.2. Dataset

3.3. Coding Schemes

3.3.1. Race and Gender

3.3.2. Body Type

3.3.3. Sexualization

4. Results

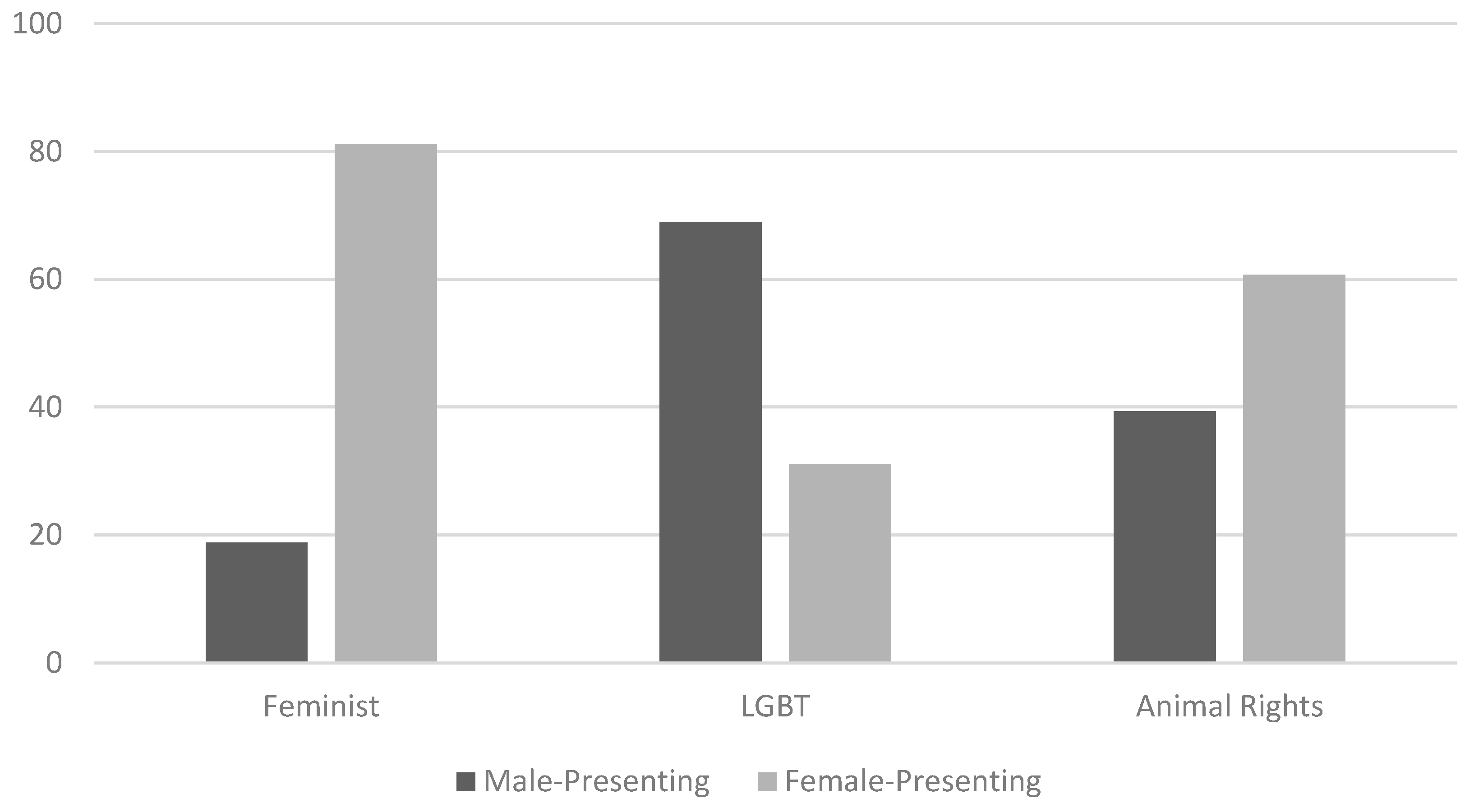

4.1. Gender

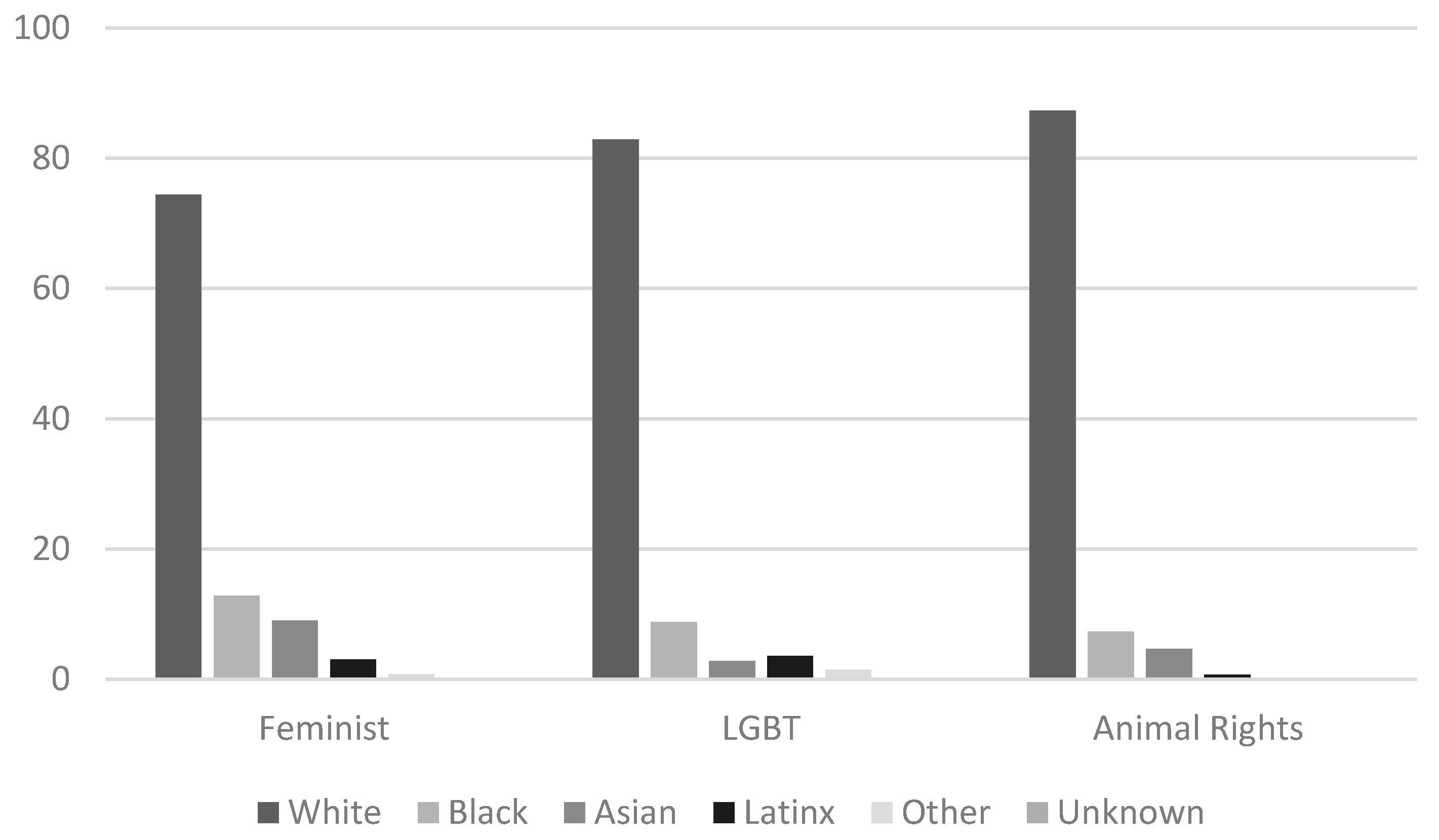

4.2. Race

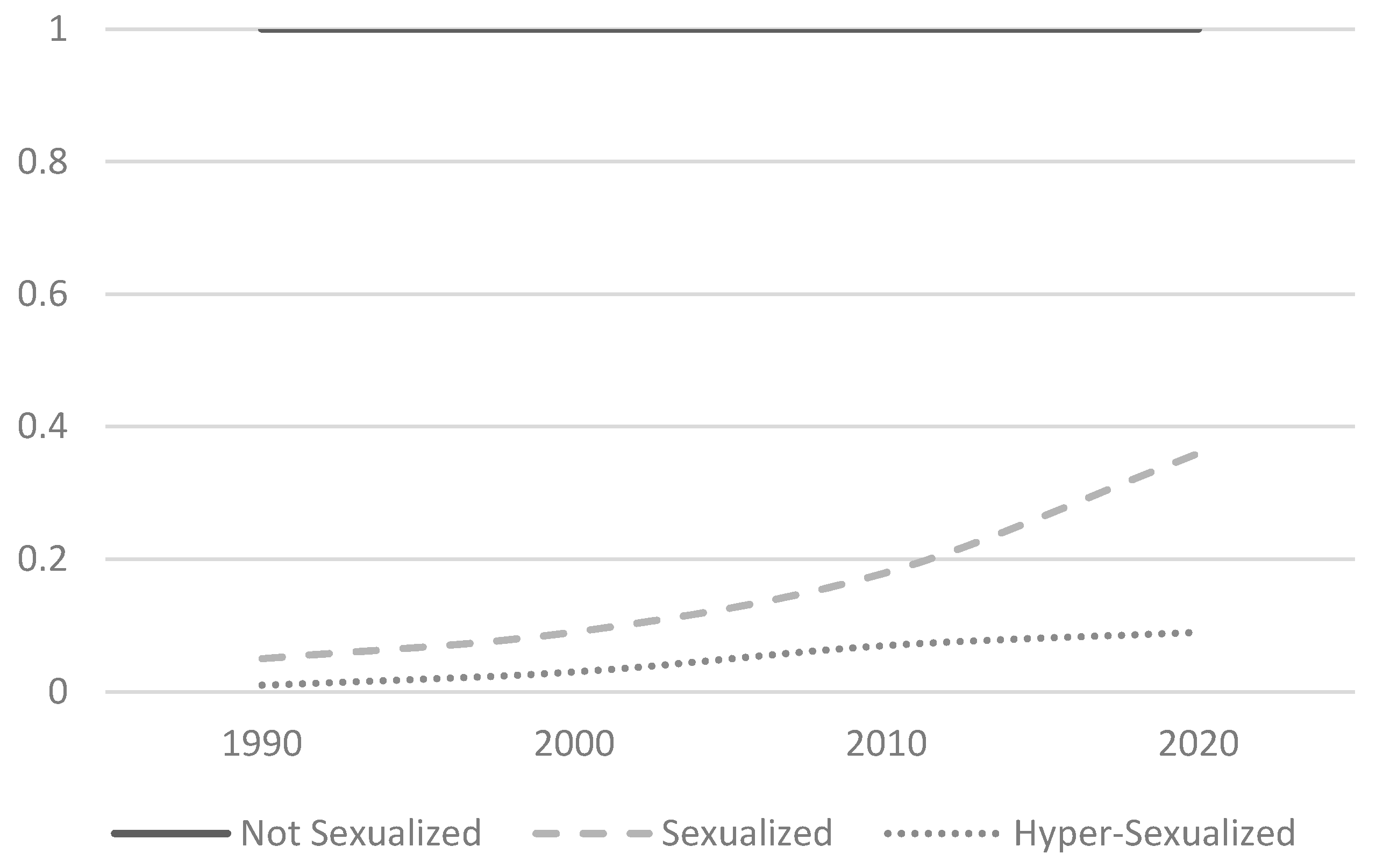

4.3. Sexualization

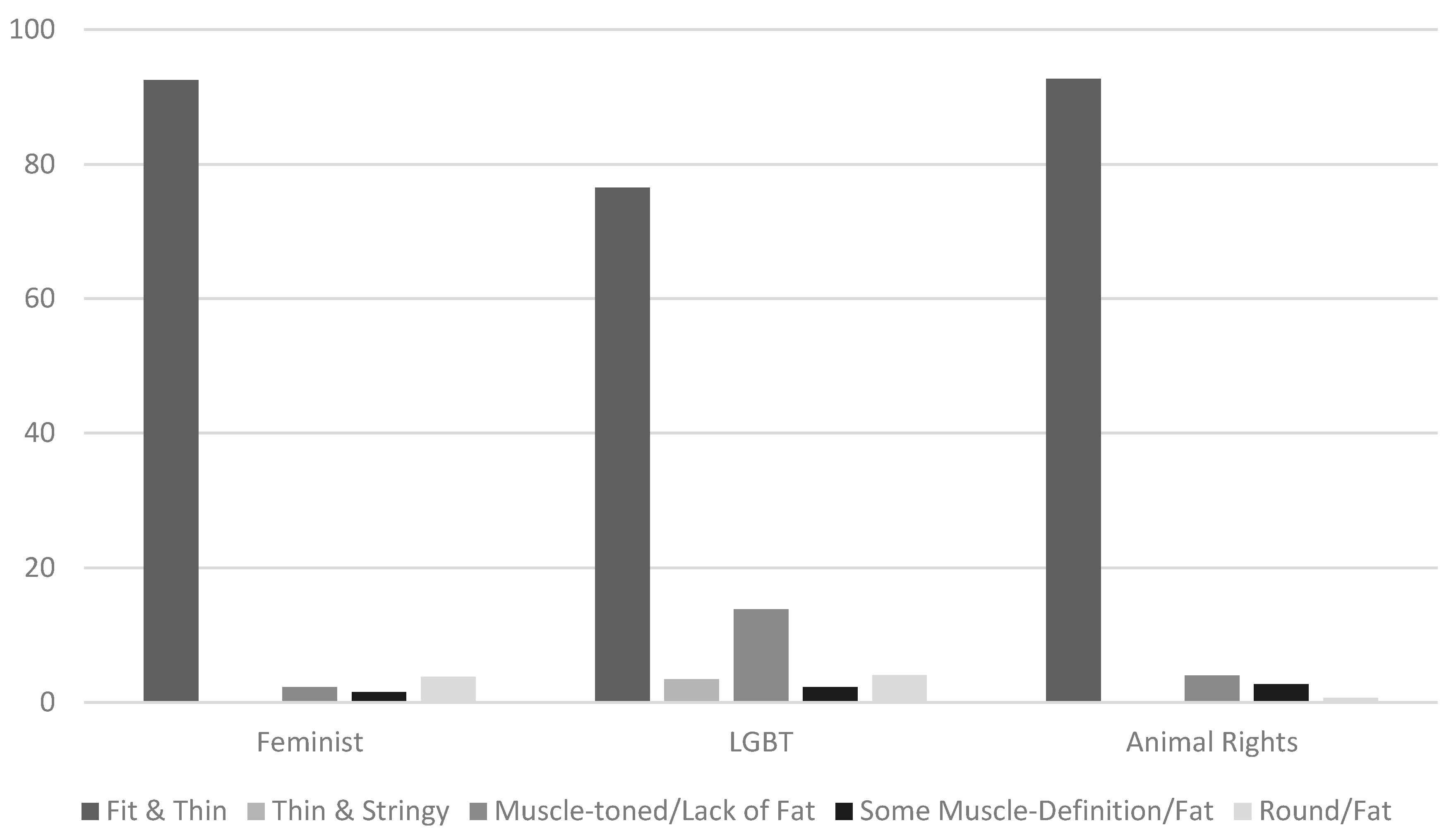

4.4. Body Type

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Race | |

| 0 | White |

| 1 | African American |

| 2 | Asian |

| 3 | Latinx of Color |

| 4 | Other |

| 5 | Unknown/Undetermined |

| Gender | |

| 0 | Male-presenting |

| 1 | Female-presenting |

| Body Type | |

| 0 | Ecto-Mesomorph (Fit & Thin) |

| 1 | Ectomorph (Thin/Stringy Muscles) |

| 2 | Mesomorph (Muscle-toned, lack of fat) |

| 3 | Endo-Mesomorph (Some muscle definition/excess fat) |

| 4 | Endomorph (Round/excess fat) |

| Sexualization 20 | |

| 0 | Not at all sexualized (0–4) |

| 1 | Sexualized (5–9) |

| 2 | Highly sexualized (10–23) |

References

- Gamson, W.; Modigliani, A. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 95, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W.; Croteau, D.; Hoynes, W.; Sasson, T. Media images and the social construction of reality. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1992, 18, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, B. Race as a “feeble matter” in veganism: Interrogating whiteness, geopolitical privilege, and consumption philosophy of “cruelty-free” products. J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2010, 8, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, B. Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, D. Vegetarianism: Movement or Moment? Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guither, H. Animal Rights: History and Scope of a Radical Social Movement; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Should people of color support animal rights? Anim. Law 2009, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad, M. Archaeology of a humane society: Animality, savagery, Blackness. In Species Matters: Humane Advocacy and Cultural Theory; DeKoven, K., Lundblad, M., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C. We are what we eat: Feminist vegetarianism and the reproduction of racial identity. Hypatia 2007, 22, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, A. Being a sistah at PETA. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- VegNews Magazine. Available online: http://vegnews.com/articles/page/do?pageId=4438&catId=5 (accessed on 11 November 2015).

- Terry, B. Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African American Cuisine; Da Capo Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, B. The Inspired Vegan: Seasonal Ingredients, Creative Recipes, Mouthwatering Menus; Da Capo Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Forson, P. Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Inness, S. Secret Ingredients: Race, Gender, and Class at the Dinner Table; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bahna-James, T.S. Journey towards compassionate choice: Integrating vegan and sistah experience. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, D. On being Black and vegan. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, M. The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery; Mirror Books/I.D.E.A.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, B.; Ginsberg, C. Animal rights as a post-citizenship movement. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglechart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jasper, J. The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory; The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.J.; Donovan, J. Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gaarder, E. Women and the Animal Rights Movement; Rutgers University Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer, L.; Adams, C. Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, B. Brutal: Manhood and the Exploitation of Animals; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deckha, M. Disturbing images: PETA and the feminist ethics of animal advocacy. Ethics Environ. 2008, 13, 35–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, C. Tied oppressions: An analysis of how sexist imagery reinforces speciesist sentiment. Brock Rev. 2011, 12, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn, C. The role of professionalization regarding female exploitation in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement. J. Gender Stud. 2013, 24, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B. Making a Killing: The Political Economy of Animal Rights; AK Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chasin, A. Selling out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. Women, Race, & Class; First Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart, R.; Oegema, D.; Klandermans, B. Media coverage and organizational support in the Dutch environmental movement. Mobilization 2005, 10, 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K.; Biggs, M. The dynamics of protest diffusion: Movement organizations, social networks, and news media in the 1960 sit-ins. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 752–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W. Bystanders, public opinion, and the media. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements; Snow, D., Soule, S., Kriesi, H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro, V. The media politics of social protest. Mobilization 1997, 2, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno, V.; Danaher, W. Media and mobilization: The case of radio and Southern textile worker insurgency, 1929 to 1934. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 66, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, E.; Caren, N.; Olasky, S.; Stobaugh, J. All the movements fit to print; who, what, when, where, and why SMO families appeared in the New York Times in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; McPhail, C.; Smith, J. Images of protest: Dimensions of selection bias in media coverage of Washington demonstrations, 1982 and 1991. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.; Maney, G. Political processes and local newspaper coverage of protest events: From selection bias to triadic interactions. Am. J. Sociol. 2000, 106, 463–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Lichbach, M. To the Internet, from the Internet: Comparative media coverage of transnational protests. Mobilization 2003, 8, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, J.; Schussman, A. The new site of activism: On-line organizations, movement entrepreneurs, and the changing location of social movement decision making. Res. Soc. Mov. Conflicts Chang. 2003, 24, 155–187. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, P.; Reese, S. Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content, 2nd ed.; Longman Publishers: White Plains, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, A. Television and socialization of the minority child. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.; Gutierrez, F. Race, Multiculturalism, and the Media: From Mass to Class Communication; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications. NAMIC and WICT Cable Telecommunications Industry Workforce Diversity Survey; NAMIC and WICT: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, R.; Loomis, J.; Soja, M. Race relations on prime time television. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Images of women’s sexuality in advertisements: A content analysis of Black- and white-oriented women’s and men’s magazines. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.; Greenburg, B. The portrayal of racial minorities on prime-time television. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.; Stern, S. Representations of race in television commercials: A content analysis of prime-time advertising. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollon, D.; Keheler, T.; Madeiros, J.; Ortega, N.; Sebastian, J.; Sen, R. Moving the Race Conversation Forward: How the Media Covers Racism, and Other Barriers to Productive Racial Disclosure; Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane, S.; Messineo, M. The perpetuation of subtle prejudice: Race and gender imagery in 1990s television advertising. Sex Roles 2000, 42, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G. The impact of television on the self-concept development of minority group children. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Spurlock, J. Television, ethnic minorities, and mental health: An overview. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H. Watching race: television and the struggle for blackness; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koçieda, A. Understanding racism. Available online: http://veganfeministnetwork.com/resources/understanding-racism-101/ (accessed on 11 April 2016).

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D. Hollywood Diversity Brief: Spotlight on Cable Television; Ralph, J., Ed.; Bunche Center for African American Studies: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, R.; Burnett, T.; Diller, T.; Rankin-Williams, E. Gender representation in television commercials: Updating an update. Sex Roles 2000, 43, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, E.; Trautner, M. Equal opportunity objectification? The sexualization of men and women on the cover of Rolling Stone. Sex. Cult. 2011, 15, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L. The effects of gender and music video imagery on sexual attitudes. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 139, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanis, K.; Covell, K. Images of women in advertisements: Effects on attitudes related to sexual aggression. Sex Roles 1995, 32, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, N.; Covell, K. The impact of women in advertisements on attitudes towards women. Sex Roles 1997, 36, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamuth, N.; Check, J. The effects of mass media exposure on acceptance of violence against women: A field experiment. J. Res. Personal. 1981, 15, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundorf, N.; D’Alessio, D.; Allen, M.; Emmers-Sommer, T. Effects of sexually explicit media. In Mass Media Effects Research: Advances through Meta-Analysis; Preiss, R., Gayle, B., Burrell, N., Allen, M., Bryant, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. Does television exposure affect adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlation and experimental confirmation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J.; Stevens, J.; Henson, K.; Hopper, M.; Smith, S. A picture is worth twenty words (about the self): Testing the priming influence of visual sexual objectification on women’s self-objectification. Commun. Res. Rep. 2009, 26, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groesz, L.; Levine, M.; Murnen, S. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrom, A. The effects of the media on body image: A meta-analysis. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2004, 48, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Hamilton, H.; Jacobs, M.; Angood, L.; Dwyer, D. The influence of fashion magazines on body image satisfaction of college women: An exploratory analysis. Adolescence 1997, 32, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.; Andreyeva, T.; Brownwell, K. Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination on America. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorsky, J. Is Obesity as dangerous to your wealth as to your health? Res. Aging 2004, 26, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, V.; Clarke, J. Race and gender in the media: A content analysis of advertisements in two mainstream Black magazines. J. Black Stud. 2008, 39, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, L.G.; Prividera, L. Communicating about race and health: A content analysis of print advertisements in African American and general readership magazines. Health Commun. 2007, 21(3), 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. Impressions of personality bases on body forms: An application of Hillestad’s model of appearance. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1990, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. People QuickFacks 2012. Available online: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html (accessed on 11 November 2015).

- Lindsey, L. Gender Roles: A Sociological Prospective, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dhoest, A.; Simons, N. Questioning queer audiences: Exploring diversity in lesbian and gay men’s media uses and readings. In The Handbook of Gender, Sex and Media; Ross, K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 260–276. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Y.; Tiggemann, M.; Kirkbride, A. Those speedos becomes them: The role of self-objectification in gay and heterosexuals men’s body image. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, K.; Murnen, S.; Krause, A. Low-cut shirts and high-heeled shoes: Increased sexualization across time in magazine descriptions of girls. Sex Roles 2013, 69, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T.; Carpenter, C. An update on sex in magazine advertising. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2004, 81, 823–837. [Google Scholar]

- Van Amsterdam, R. Big fat inequalities, thin privilege: An intersectional perspective on “body size”. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2013, 20, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1A reviewer has suggested that this disconnect could also stem from a long history of white supremacist brutality against Black communities via the use of dogs.

- 3Although veganism and activism for other animals are often distinct, the two concepts are often used interchangeably. Most Nonhuman Animal rights efforts idealize veganism as foundational to anti-speciesist efforts, and the public tends to conflate the two. The Nonhuman Animal rights literature included in this study happens to be vegan-based (non-vegan magazine sources were not deemed suitable for analysis due to low numbers of human subjects). For these reasons, veganism will sometimes be used to reference Nonhuman Animal rights.

- 4The Nonhuman Animal rights movement is considered to be a “post-citizenship” movement [19]. Participants of post-citizenship movements generally advocate on behalf of others or for non-material values and morals. They also tend to be well-integrated and relatively privileged in their society [20,21]. This may partially explain why disadvantaged demographics are underrepresented in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement.

- 5This analysis was conducted in 2013 and was based on contributor avatars listed on One Green Planet’s website: http://www.onegreenplanet.org/channel/about-us. One Green Planet is an influential online webzine and community featuring many of the most prominent authors and activists in the movement.

- 6This analysis was conducted in 2013 according to the guests listed on the ARZone podcast page: http://arzone.ning.com/page/podcasts. Guests who made repeat appearances in more than one episode were counted once for each appearance. The regular hosts were excluded. ARZone is an academically-focused online community that also features the most prominent authors and activists in Nonhuman Animal rights mobilization.

- 7Vegan consumer items of convenience and comfort are, arguably, helpful in the transition to veganism and sustaining a vegan lifestyle. Torres’ critique, however, points to the problematic ways in which the consumer focus of veganism undermines its political capacity.

- 8It is worth considering that nonhuman subjects (who are less likely to present gender norms) could have an equalizing effect and may actually welcome underrepresented groups. Furthermore, nonhuman imagery is heavily utilized by the Nonhuman Animal rights movement to stimulate empathy and mobilization. This relationship between nonhuman cover subjects and propensity for participation would be worth exploring in future research.

- 9Three times in 2000, 10 times in 2001, 9 times in 2002, and 5 times in 2004.

- 10Bust Magazine (11); Equality (23); and The Advocate (6).

- 11For example, the Winter 2007 issue of Equality depicted a blurred face and an outreaching hand. Gender was undeterminable, and because the library scan was in black and white, the race of the subject was also unknown.

- 12VegNews 2001, January (4).

- 13VegNews 2001, February (5).

- 14VegNews 2001, May/June (8,9).

- 15VegNews 2004, September/October (39); 2004, January/February (41); 2008, January/February (59).

- 16This is the gender-neutral term meant to include trans and gender fluid persons.

- 17Admittedly, the framework of the analysis and its focus only on cover subjects makes addressing gender variance difficult; it also reinforces a limiting gender binary.

- 18Please see the original study for further explanation on how variables we’ve included were coded and why.

- 19Recall that the sample from the feminist movement features more women, but these women are more likely to be diverse in race and body type.

- 20See Hatton and Trautner’s [61] study cited in this manuscript for a full description of the sexualization coding scheme.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wrenn, C.L.; Lutz, M. White Women Wanted? An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Social Justice Magazines. Societies 2016, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6020012

Wrenn CL, Lutz M. White Women Wanted? An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Social Justice Magazines. Societies. 2016; 6(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleWrenn, Corey Lee, and Megan Lutz. 2016. "White Women Wanted? An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Social Justice Magazines" Societies 6, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6020012

APA StyleWrenn, C. L., & Lutz, M. (2016). White Women Wanted? An Analysis of Gender Diversity in Social Justice Magazines. Societies, 6(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc6020012