The Status of National Legal Frameworks for Valuing Compensation for Expropriated Land: An Analysis of Whether National Laws in 50 Countries/Regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America Comply with International Standards on Compensation Valuation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Legal Reform as a Potential Solution to Insufficient Compensation

1.2. Road Map

2. International Standards on the Valuation of Compensation

3. Background and Methodology

4. The Usefulness of this Research

5. Research Findings

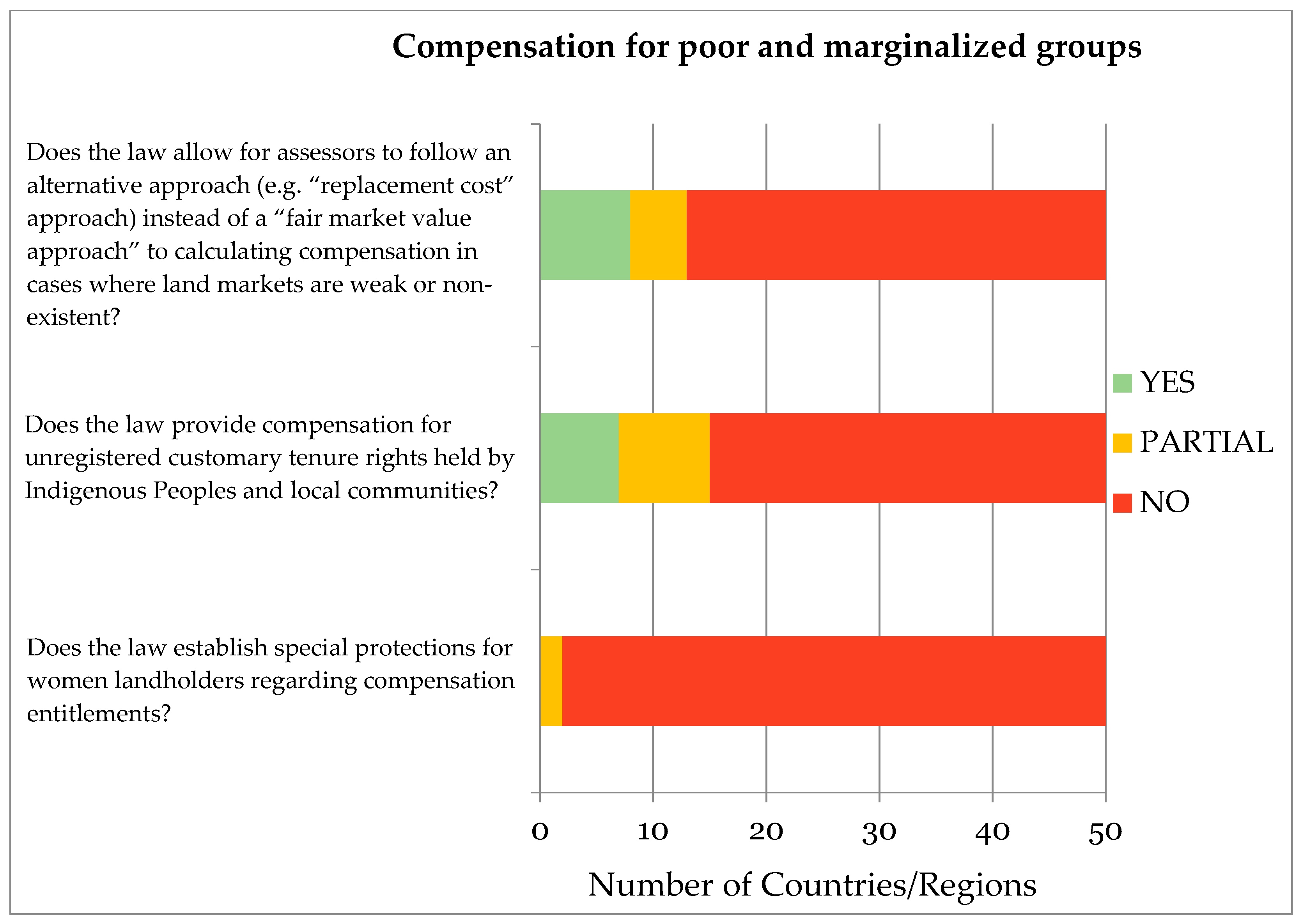

5.1. Compensation for Poor and Marginalized Groups

5.1.1. The “Fair Market Value” Approach

“Assessing the market value of a land parcel is not always simple, particularly where land markets are weak. A variety of complex factors must often be considered… It may not always be possible to determine compensation based on market value. Alternative approaches vary depending on the political economy of a country, the qualities of the land acquired, and the nature of the land rights.”

“Blight condemnations, urban renewal programs, and redevelopment projects which often serve as the ‘public use’ justification for eminent domain- all affect, not coincidentally, assets belonging to poor property owners … Stronger communities are more likely to have the resources and influence to avoid the damaging effects of eminent domain without government assistance. Politically strong communities may use their political ties and influence to fend off expropriation, and economically strong communities may be safe because of the high costs that the state would incur by taking their land.”[41]

5.1.2. Compensation for Unregistered Customary Tenure Holders

5.1.3. Special Protections Ensuring Women Landholders Receive Fair Compensation

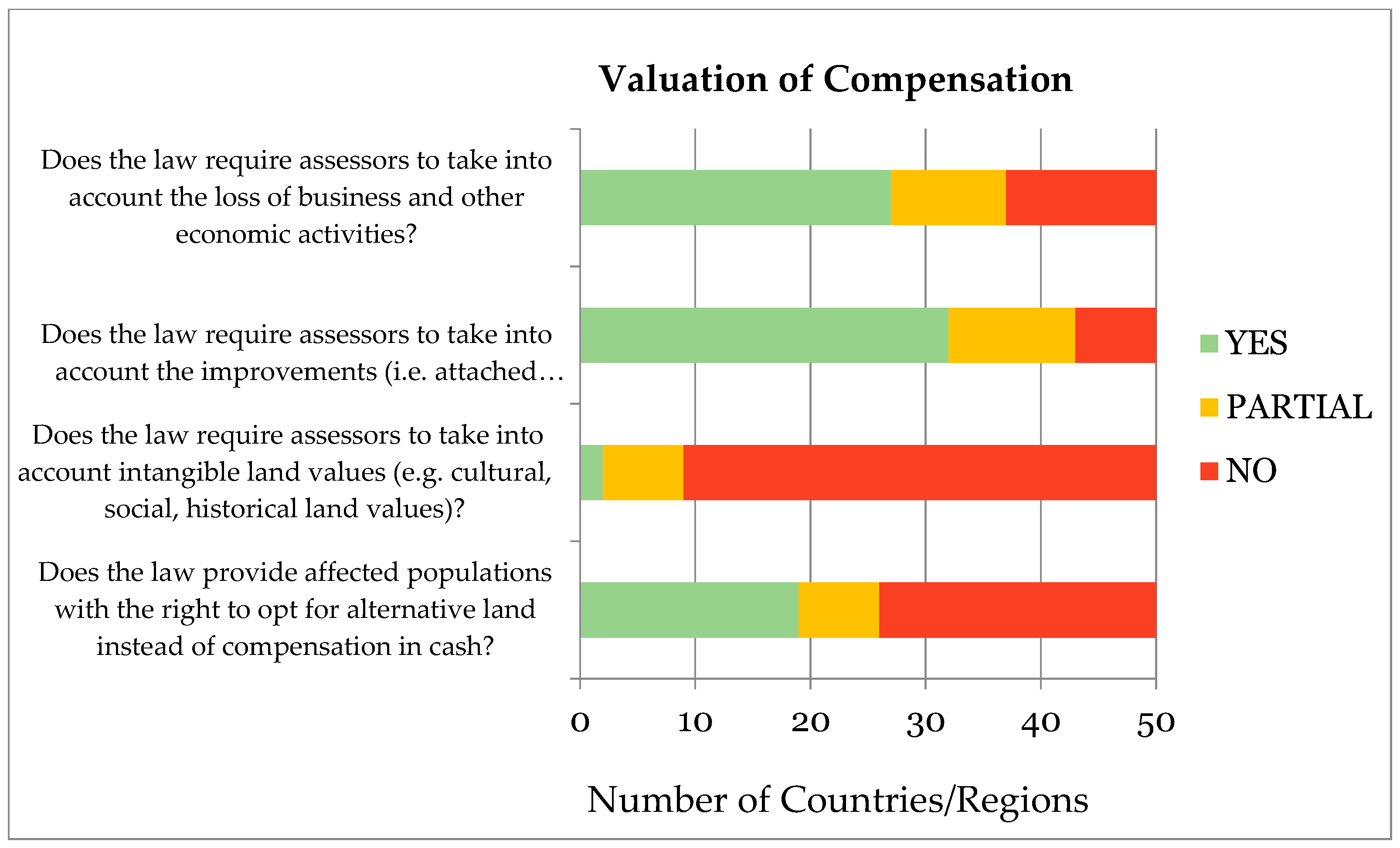

5.2. Valuation of Compensation

5.2.1. Compensation for Loss of Economic Activities and Improvements Made on the Land

“Compensation should be for buildings and other improvements to the land acquired; for the reduction in value of any land retained as a result of the acquisition; and for any disturbances or other losses to the livelihoods of the owner and occupants caused by the acquisition and dispossession. The disturbance accompanying compulsory acquisition often means that people lose access to the sources of their livelihoods. This can be due to a farmer losing agricultural fields, a business owner losing a shop, or a community losing its traditional lands.”

5.2.2. Compensation for Intangible Land Values (e.g., Cultural, Spiritual, and Historical Values)

5.2.3. The Right of Affected Populations to Opt for Alternative Land Instead of or in Addition to a Cash Payment of Compensation

“providing suitable alternative land may be difficult in the light of current population pressures on the land…However, many owners and occupants may prefer to receive land as compensation rather than money…resettlement of vulnerable people on alternative land is required when the loss of their land means a loss of their livelihoods.”

He notes that this obligation may arise in cases where land held by large communities is expropriated.“the establishment of an ongoing relationship with the state and individuals who have been subject to expropriation creates financial uncertainty and entails significant negation and monitoring costs that exceed those associated with one-shot compensation. Therefore, the use of a direct resettlement remedy should be limited only to instances where the collective dimension of the state’s pluralistic obligation arises.”

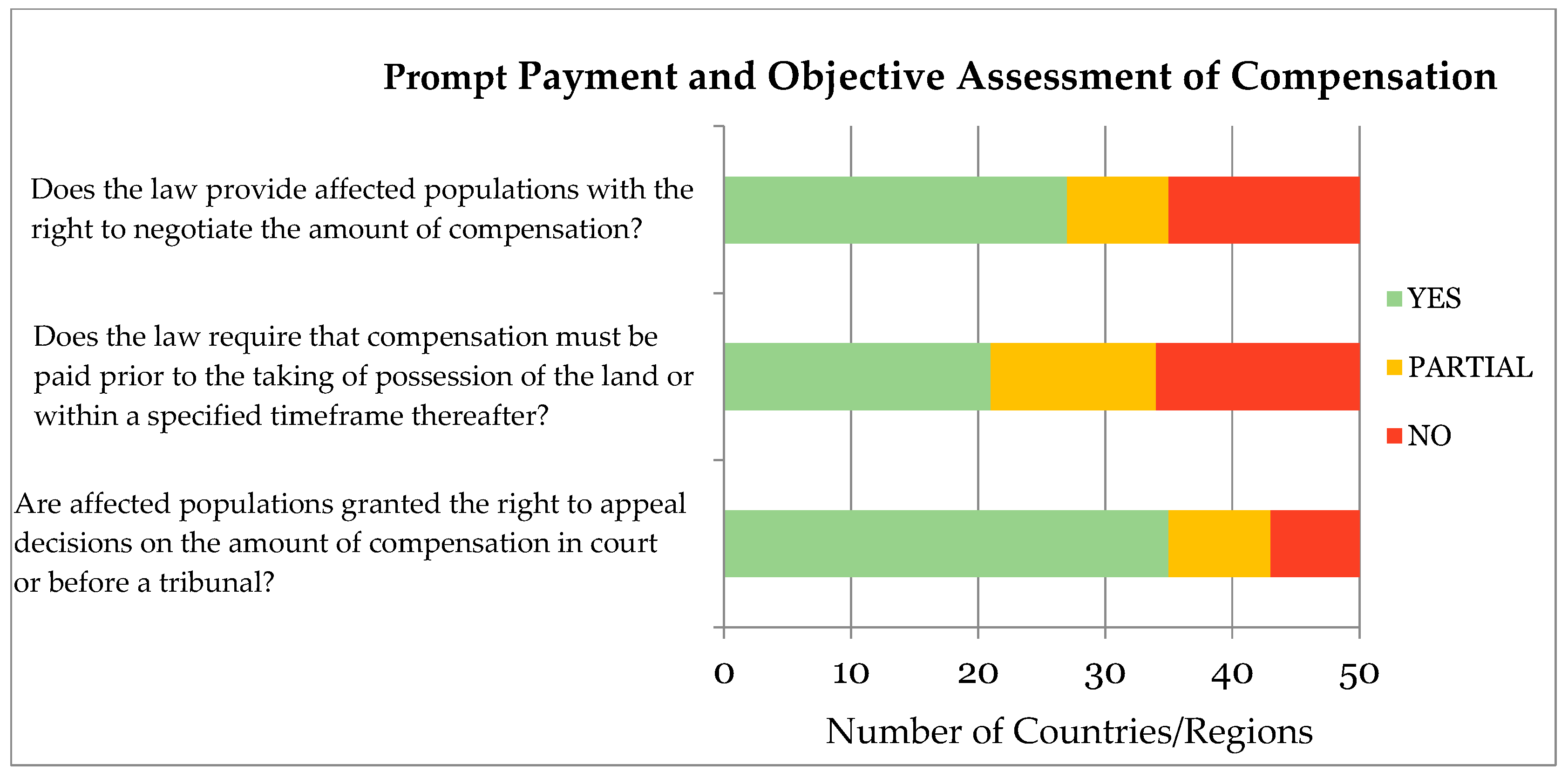

5.3. Prompt Payment and Objective Assessment of Compensation

5.3.1. The Affected Populations’ Right to Negotiate Compensation Amounts [100]

5.3.2. Delays in Compensation Payments

“The speed at which compensations are paid to property owners is also very slow. This may be attributed to the lack of planning on the part of the expropriating institution and the inadequate understanding of the need to pay compensation on the part of the government, which results in the poor budgetary allocation to the institutions saddled with the responsibility of land acquisition in the country.”[111]

5.3.3. A Right to Challenge Compensation Decisions in Court or before a Tribunal

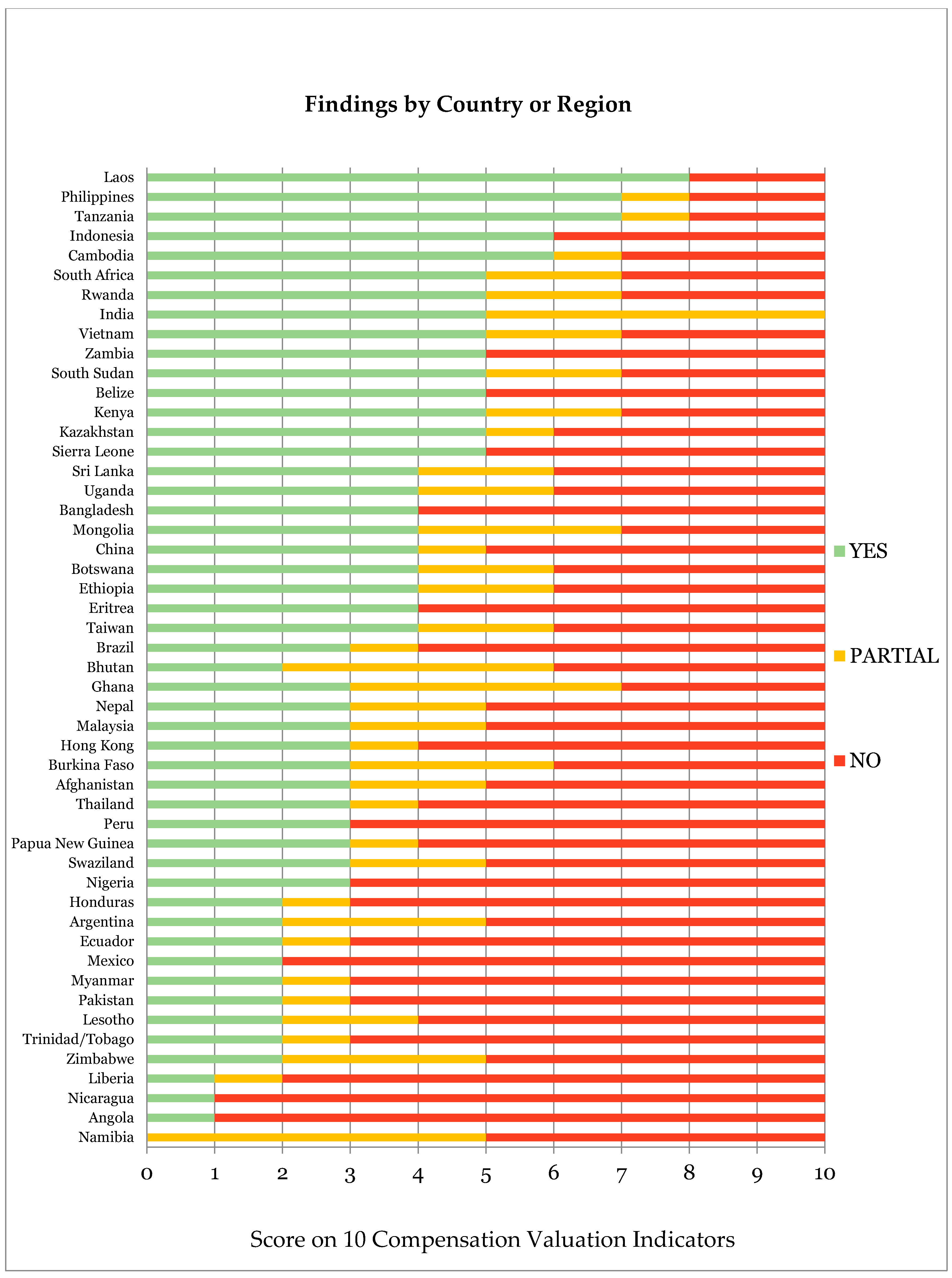

5.4. Overall Conclusions from the 10 Compensation Valuation Indicators

6. Recommendations

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- “Expropriation” is the power of government to acquire privately held tenure rights, without the willing consent of the tenure holder, in order to serve a public purpose or otherwise benefit society. In this paper, “expropriation” refers to eminent domain, takings, compulsory purchases, compulsory acquisitions, and other names given to this government power around the world. “Affected populations” are the populations whose tenure rights are affected by expropriation. “Tenure rights” are the rights of individuals or groups, including Indigenous Peoples and communities, over land and resources. Tenure rights include, but are not limited to ownership, freehold possession rights, use rights, and rental, customary and collective tenure arrangements. The bundle of tenure rights can include the right of access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, and alienation.

- Van Eerd, M.; Banerjee, B. Working Paper I: Evictions, Acquisition, Expropriation and Compensation: Practices and Selected Case Studies; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keliang, Z.; Prosterman, R.; Jianping, Y.; Ping, L.; Riedinger, J.; Yiwen, O. The Rural Land Question in China: Analysis and Recommendations Based on a Seventeen-Province Survey. Intl. Law Politics 2006, 38, 761–839. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework: Country Reports; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework Final Report: Nigeria; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P. Fair Notice and Fair Adjudication: Two Kinds of Legality. Univ. Penn. Law Rev. 2005, 154, 335–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur, G. The Rule of Law: Is the Line Between the Formal and the Moral Blurred? In Law, Liberty, and the Rule of Law; Flores, I.B., Hiima, K.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, J. The Rule of Law and Its Virtues in The Authority of Law: Essays on Law and Morality; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 210, 213, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Dagan, H. Expropriatory Compensation, Distributive Justice, and the Rule of Law. In Rethinking Expropriation Law I: Public Interest in Expropriation; Hoops, B., Marais, E.J., Mostert, H., Sluysman, J.A.M.A., Verstappen, L.C.A., Eds.; Eleven International Publishing: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Dagan notes that “at times, commitment to the rule of law implies allowing, or even preferring, that the social practice of a legal topic be formed around a vague but informative standard….[but] by contrasts, open-ended references to justice, fairness, good faith, or reasonableness….fail to ensure proper predictability or properly constrain law appliers. They should therefore be criticized as an invitation to ad hoc discretion, which affronts the rule of law.”

- Cernea, M. Impoverishment Risks, Risk Management, and Reconstruction: A Model of Population Displacement and Resettlement. In Proceedings of the UN Symposium on Hydropower and Sustainable Development, Beijing, China, 27–29 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Acquiring bodies are the government and private entities that carry out the expropriation, compensation, and resettlement processes, including government departments, ministries, and agencies or, in some cases, private entities, such as companies investing in land.

- Food and Agricultural Organizations of the United Nations (FAO). The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries, and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49, 1960.

- Cernea, M.M.; Mathur, H.M. Can Compensation Prevent Impoverishment? Reforming Resettlement through Investments and Benefit-Sharing; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M.M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The indicators ask whether laws require assessors to account for various tangible and intangible land values when calculating compensation, and whether there are legal processes in place that allow affected person to negotiate compensation amounts, receive prompt payments, and hold governments accountable by appealing compensation decisions. The indicator data is open access and available on Land Portal’s Land Book country pages. See http://landportal.info/book/countries/.

- Kropiwnicka, M. A Brief Introduction to the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security; Actionaid: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). Convention No. 169, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989; United Nations. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, G.A. Res. 61/295, U.N. Doc. A/ RES/61/295.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Interlaken Group and Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI). Respecting Land Forest Rights: Risks, Opportunities, and a Guide for Companies; RRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, S.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Land Tenure Studies 10: Compulsory Acquisition of Land and Compensation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Environmental and Social Standard 5 Land Acquisition, Restrictions on Land Use and Involuntary Resettlement; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliarino, N. Encroaching on Land and Livelihoods: How National Expropriation Laws Measure Up Against International Standards; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliarino, N. Country-Level Legal Protection of Landholders Displaced by Expropriation. 2017; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- See e.g., the Environmental Democracy Index (www.environmentaldemocracyindex.org); LandMark indicators on the legal security of indigenous and community lands (www.landmarkmap.org); World Resources Institute Rights to Resource Map (http://www.wri.org/resources/maps/rights-to-resources).

- In parts of Africa and other regions, where all land is legally owned “or held in trust for the people” by the government, governments are not always required to follow expropriation procedures when infringing on land and resource rights. For instance, governments can often designate, convert, lease, allocate, grant concessions to, or otherwise alienate land classified by law as “state-owned” without following expropriation procedures. The legal question of whether expropriation procedures should apply is complex and can only be answered on a case-by-case basis. This paper examines whether compensation rights are recognized and protected by law, assuming that national-level expropriation procedures apply.

- Kashwan, P. Forest Policy, Institutions, and Redd+ in India, Tanzania, and Mexico. Glob. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, J.; Khan, M. Land Acquisition Law: Winking at the States. The Hindu. 2 November 2016. Available online: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/Winking-at-the-States/article16086906.ece (accessed on 3 April 2017).

- See section V: “yes” scores receive green colors, “partial” scores receive yellow colors, and “no” scores receive red colors.

- True Price and University of Groningen. Towards a Protocol on Fair Compensation in Case of Land Tenure Changes. Input Document to a Participator Process; True Price: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Raw Legal Indicator Data Can be Found on Land Portal’s Land Book Country Pages. Available online: www.landportal.info (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- See www.landportal.info for detailed explanation of indicator scores for each country.

- Adopting LandMark’s definition of “communities”, this paper defines “communities” (or “IPLCs”) as “groupings of individuals and families that share interests in a definable local land area within which they normally reside… (1) [communities usually] have strong connections to particular areas or territories and consider these domains to be customarily under their ownership and/or control. (2) They themselves determine and apply the rules and mechanisms through which rights to land are distributed and governed… (3) Collective tenure and decision-making characterize the system. Usually, all or part of the community land is owned in common by members of the community and to which rights are distributed”. Wily, L.A.; Veit, P.; Smith, R.; Dubertre, F.; Reytar, K.; Tagliarino, N. Guidelines for Researching, Scoring and Documenting Findings on ‘What National Laws Say About Indigenous & Community Land Rights’ Methodology Document from LandMark: The Global Platform of Indigenous and Community Lands; LandMark: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: www.landmarkmap.org (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- ESS5 provides “Where functioning markets exist, replacement cost is the market value as established through independent and competent real estate valuation, plus transaction costs. Where functioning markets do not exist, replacement cost may be determined through alternative means, such as calculation of output value for land or productive assets, or the un-depreciated value of replacement material and labor for construction of structures or other fixed assets, plus transaction costs. In all instances where physical displacement results in loss of shelter, replacement cost must at least be sufficient to enable purchase or construction of housing that meets acceptable minimum community standards of quality and safety.” World Bank. Environmental and Social Framework; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, J. PPP Insights: Compulsory Acquisition of Land and Compensation in Infrastructure Projects; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework Final Report for Peru; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- “[In] particularly remote, rural settings, markets are not sufficiently active to provide reliable information about prices. Even when markets do provide reliable information about the value of the expropriated land, it may not be possible to identify comparable land for purchase.” Asian Development Bank. Compensation and Valuation in Resettlement: Cambodia, People’s Republic of China, and India; Rural Development Institute: Seattle, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Merril, T. Incomplete Compensation for Takings. N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J. 2002, 11, 116. [Google Scholar]

- United States v. Commodities Tradition Corp., 339 U.S. 121, 123, 1950.

- Mahapatra, R. Acquisition Made Easy. Down Earth. 2011. Available online: http://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/acquisition-made-easy-33633 (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- Stern, S. Expropriation Effects on Residential Communities. In Rethinking Expropriation Law II: Context, Criteria, and Consequences of Expropriation; Hoops, B., Marais, E.J., Mostert, H., Sluysman, J.A.M.A., Verstappen, L.C.A., Eds.; Eleven International Publishing: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 359–391. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A.; Parchomovsky, G. Takings Reassessed. Va. Law Rev. 2001, 87, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Parchomovsky, G. Taking Compensation Private. Stanf. Law Rev. 2007, 59, 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dyrkolbotn, S. On Benefit Sharing and the Compensatory Approach to Economic Development Takings. In Rethinking Expropriation Law II: Context, Criteria, and Consequences of Expropriation; Hoops, B., Marais, E.J., Mostert, H., Sluysman, J.A.M.A., Verstappen, L.C.A., Eds.; Eleven International Publishing: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 319–355. [Google Scholar]

- Freilich, R.H. Condemnation Blight: Analysis and Suggested Solutions. In Current Condemnation Law: Takings, Compensation and Benefits, 2nd ed.; Akerman, A.T., Dynkowski, D.W., Eds.; American Bar Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M. Compensation and benefit sharing: Why resettlement policies and practices must be reformed. Water Sci. Eng. 2008, 1, 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Esteves, A.M.; Aucamp, I.; Franks, D. Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for Assessing and Managing the Social Impacts of Projects; International Association for Impact Assessment: Fargo, ND, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krie, J.; Serkin, C. Public Ruses. Mich. St. Law Rev. 2004, 2004, 859–875. [Google Scholar]

- Radin, J. Reinterpreting Property; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1993; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. Just Undercompensation: The Idiosyncratic Premium in Eminent Domain. Columbia Law Rev. 2013, 113, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Belize, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Laos, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania.

- Government of Tanzania. Village Land Regulations; Section 10; Government of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2001.

- Government of Sierra Leone. Public Lands Ordinance; Chapter 116, Section 18(1) (g); Government of Sierra Leone: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 1960.

- Mongolia, Bhutan, India, Kenya, Lesotho.

- Afghanistan, Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, China, Ecuador, Eritrea, Honduras, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Liberia, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

- Lindsay, J.; Deininger, K.; Hilhorst, T. Compulsory Land Acquisition in Developing Countries: Shifting Paradigm or Entrenched Legacy; Lee, H., Kim, I., Somin, I., Eds.; Eds. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliarino. Avoiding the Worst-Case Scenario: Whether Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities are Vulnerable to Expropriation without Compensation. In Proceedings of the Annual World Bank Land and Poverty Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 20–24 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rainforest Foundation. Peru and Climate Crossroad; Rainforest Foundation: London, UK, 2015; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, M.; Selebalo, C.; Boydell, S. Towards the Valuation of Unregistered Land. In Proceedings of the Annual World Bank Land and Poverty Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI). Who Owns the World’s Land? A Global Baseline of Formally Recognized Indigenous and Community Land Rights; RRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wily, L. Compulsory Acquisition as Constitutional Matter: The Case in Africa. J. Afr. Law 2017. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Laos, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia.

- Section 75(3) of South Sudan’s Land Act 2009 states “Where any land is expropriated for public purpose and it is necessary to remove any person therefrom in customary occupation, compensation shall be paid as may be agreed upon” Section 39(3) provides that “right of ownership and derivative rights to land may be proven by any other practices recognized by communities in Southern Sudan in conformity to equity, ethics and public order.” Government of South Sudan. Land Act, 2009.

- Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, India, Kenya, Liberia, Rwanda, South Africa, Vietnam.

- Government of South Africa. Interim Protection of the Informal Land Rights Act, 1996 (amended 2015), Section 2(3).

- Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Belize, Bhutan, Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Lesotho, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Zimbabwe.

- Oxfam International. Unearthed: Land, Power and Inequality in Latin America; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Law of the Land: Women’s Rights to Land. Available online: http://www.landesa.org/resources/property-not-poverty/ (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- United Nations. Realizing Women’s Rights to Land and Other Productive Resources; HR/PUB/13/04; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-La Viña, C.; Morarji, M. Making Women’s Voices Count in Community Decision-making on Land Investments; Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, J.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Quisumbing, A. The Gender Implications of Large-Scale Land Deals. Discussion Paper 01056; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The author acknowledges that the topic of “women’s land rights” is not sufficiently covered in this article. When assessing this indicator, the author did not consider, beyond national expropriation and compensation procedures, the range of other constitutional, legislative, and regulatory provisions that address women’s access and rights to land. Such a legal analysis is beyond the scope of this study since the focus of this comparative study was on the national-level compensation procedures.

- “Improvements” refers to the land’s attached and unattached assets (e.g., crops, buildings).

- Rose, H.; Mugisha, F.; Kananga, A.; Clay, D. Implementation of Rwanda’s Expropriation Law and Its Outcomes on the Population. In Proceedings of the Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Final Report: Brazil; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh, Belize, Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Lesotho, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tanzania, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam.

- Government of Indonesia. Acquisition of Land for Development in the Public Interest, Law No. 2 of 2012; Art. 33(f); Government of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2012.

- Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mongolia, Namibia, the Philippines, South Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe.

- Afghanistan, Angola, Argentina, Ecuador, Eritrea, Honduras, Liberia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Trinidad and Tobago, Zambia.

- Afghanistan, Angola, Bangladesh, Belize, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, China, Ethiopia, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Laos, Mexico, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Taiwan, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Vietnam, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

- Government of Belize. Land Acquisition (Public Purposes); Art. 20(b); Government of Belize: Belmopan, Belize, 2000.

- Argentina, Cambodia, Ghana, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Namibia, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Thailand, Uganda.

- Government of Kazakhstan. Law on State-Owned Property; Art. 67; Government of Kazakhstan: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2011.

- Bhutan, Ecuador, Eritrea, Lesotho, Liberia, Nicaragua, Papua New Guinea.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability, Performance Standard 7: Indigenous Peoples; IFC: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- According to Bell and Parchmovosky, “Under the proposed mechanism, property owners would get to set the price of the property designated for condemnation. The government could then either take the property at the designated price or abstain, leaving the property subject to two new proposed restrictions. First, for the life of the owner, the property could not be sold for less than the self-assessed price, adjusted on the basis of the local housing price index. Second, the self-assessed price—Discounted to take account of the peculiarities of property tax assessments—Would become the new benchmark for the owner’s property tax liability.”

- Lunney, G.S. Takings, Efficiency, and Distributive Justice: A Response to Professor Dagan. Mich. Law Rev. 2000, 99, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wyman, K. The Measure of Just Compensation. UC Davis Law Rev. 2007, 41, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Bhutan. Land Act; Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2007; Section 151.

- Government of Philippines. Indigenous People’s Rights Act; Government of Philippines: Manila, Philippines, 1997; Section 71. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana, India, Laos, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Vietnam.

- Afghanistan, Angola, Argentina, Bangladesh, Belize, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Honduras, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Myanmar, Namibia, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

- Atahar, S. Development Project, Land Acquisition and Resettlement in Bangladesh: A Quest for Well Formulated National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Policy. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 306–319. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, J.; Deininger, K.; Hilhorst, T. Compulsory Land Acquisition in Developing Countries: Shifting Paradigm or Entrenched Legacy. Proceedings for the Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Afghanistan, Cambodia, Eritrea, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Mongolia, Nepal, Nigeria, Philippines, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Vietnam, Zambia.

- Argentina, Bhutan, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Taiwan, Zimbabwe.

- In some countries or regions, compensation may be provided in cash or “in kind.” In this case, the author interpreted the law as implicitly suggesting law that alternative land may be as a compensation option in some cases, though not necessarily guaranteed in every case.

- Government of Argentina. Ley No. 21.499 Nacional de Expropriaciones; Government of Argentina: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1977.

- Angola, Bangladesh, Belize, Brazil, China, Ecuador, Honduras, Hong Kong, Lesotho, Liberia, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Namibia, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda.

- The term “negotiate” as used here refers to the right to submit written or verbal claims for compensation, or, in some cases, “reach an agreement” with the government, as stated by the law. The term “negotiate” does not necessarily mean that affected populations have the final say regarding compensation amounts. In most cases, the government makes the final decision, but this decision is appealable in court or before a tribunal.

- Deininger, K.; Selod, H.; Burns, A. The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- According to Bell and Parchomovsky, the proposed “self-assessment” procedure is described as follows: at stage I, the government announces its intention to take property by eminent domain. Thereafter, at stage II, affected property owners name the price they want for their properties. Finally, at stage III, the government either proceeds with its plan and seizes the properties at the named price or abandons the proposed taking. If the government decides not to take property at the self-assessed price, the owner will retain title to the properties, but will become subject to two restrictions. First, for the life of the owner, the property cannot be sold for less than the self-assessed price. If the property is transferred for less than that price, the owner will have to pay the shortfall to the government. Second, the self-assessed price will become the benchmark for the owner’s property tax liability. As we will show, the combined effect of partial inalienability and enhanced tax liability should suffice to keep the owner honest in reporting her subjective value.

- Argentina, Belize, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Eritrea, Ghana, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia.

- Government of Papua New Guinea. Land Act, 1996, section 21, 25, 26. Available online: http://landportal.info/book/countries/PNG (accessed on 26 February 2017).

- Afghanistan, Bhutan, Ecuador, Honduras, Namibia, Nicaragua, Rwanda, Taiwan.

- Angola, Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Liberia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Zimbabwe.

- Government of Ethiopia. Proclamation No. 455/2005 Expropriation of Landholdings for Public Purposes and Payment of Compensation Proclamation. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework Final Report- Ethiopia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, W.O.; Antwi, A.; Olomolaiye, P. Compulsory land acquisition in Ghana: Policy and praxis. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework Final Report-Kenya; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Land Governance Assessment Framework Final Report-Nigeria; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Botswana, Cambodia, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Lesotho, Mexico, Philippines, Rwanda, Swaziland, Taiwan, Thailand, Uganda, Vietnam, Zimbabwe.

- Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Malaysia, Mongolia, Namibia, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago.

- Government of Trinidad and Tobago. Land Acquisition Act Ch. 58:01; Government of Trinidad and Tobago: Port of Spain, 1994; Section 22.

- Angola, Belize, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Honduras, Hong Kong, Kenya, Liberia, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Zambia.

- Government of Tanzania. Land Acquisition Act; Government of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 1967; Section 14(2), 15.

- Cotula, L. Legal Empowerment for Local Resource Control: Securing Local Rights Within Foreign Investment Projects; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Argentina, Bangladesh, Belize, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, China, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Laos, Liberia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Uganda, Zambia.

- Government of Brazil. The Law of Expropriation for Public Utility, Decree-Law No. 3.365 of June 21, 1941; Art. 28; Government of Brazil: Brasilia, Brazil, 1941.

- Botswana, Ghana, Lesotho, Myanmar, Namibia, Pakistan, Swaziland, Zimbabwe.

- Government of Swaziland. Acquisition of Property; Act No. 10 of 1961; Government of Swaziland: Mbabane, Swaziland, 1961; section 10.

- Afghanistan, Angola, Bhutan, Mexico, Nepal, Nicaragua, Vietnam.

- Section 10 of the Village Land Regulations states “The market value of any land unexhausted improvement shall be arrived at by use of comparative method evidenced by actual recent, sales of similar properties or by use of income approach or replacement cost method where the property is of special nature and not saleable.”

- Palmer, D.; Fricska, S.; Wehrmann, B. Land Tenure Working Paper 11: Toward Improved Land Governance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Rwanda. Law No. 18/2007 Relating to Expropriation in the Public. 2007; article 18. [Google Scholar]

- The Asian Development Bank’s Summary of the Handbook on Resettlement: A Guide to Good Practice (1998) provides a broad range of losses which should be accounted for in the assessment of compensation, including agricultural land house plot (owned or occupied), business premises (owned or occupied), access to forest land, traditional use rights, community or pasture land, access to fishponds and fishing places, house or living quarters, other physical structures, structures used in commercial/industrial activity, income from standing crops, income from rent or sharecropping, income from wage earnings, income from affected business, income from forest products, income from fishponds and fishing places, income from grazing land, subsistence from other shrines, religious sites, places of worship and sacred grounds, cemeteries and other burial sites, and other factors.

- In India and other countries where displaced persons are usually not consulted during the resettlement process, inability to participate and monitor the resettlement process can lead to protests and resistance among affected populations. These conflicts may delay projects and increase costs for governments and acquiring bodies.

- Hemadri, R. Dams, Displacement, Policy and Law in India; World Commission on Dams: Cape Town, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| List of Countries | Regions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Asia

| Africa

| Latin America

|

|

| List of Compensation Valuation Indicators |

|---|

|

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tagliarino, N.K. The Status of National Legal Frameworks for Valuing Compensation for Expropriated Land: An Analysis of Whether National Laws in 50 Countries/Regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America Comply with International Standards on Compensation Valuation. Land 2017, 6, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6020037

Tagliarino NK. The Status of National Legal Frameworks for Valuing Compensation for Expropriated Land: An Analysis of Whether National Laws in 50 Countries/Regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America Comply with International Standards on Compensation Valuation. Land. 2017; 6(2):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6020037

Chicago/Turabian StyleTagliarino, Nicholas K. 2017. "The Status of National Legal Frameworks for Valuing Compensation for Expropriated Land: An Analysis of Whether National Laws in 50 Countries/Regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America Comply with International Standards on Compensation Valuation" Land 6, no. 2: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6020037

APA StyleTagliarino, N. K. (2017). The Status of National Legal Frameworks for Valuing Compensation for Expropriated Land: An Analysis of Whether National Laws in 50 Countries/Regions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America Comply with International Standards on Compensation Valuation. Land, 6(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/land6020037