Abstract

Background: Malignant melanoma is the most aggressive of skin cancers and the 19th most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated age-standardized incidence rate of 2.8–3.1 per 100,000; although there have been clear advances in therapeutic treatment, the prognosis of MM patients with Breslow thickness greater than 1 mm is still quite poor today. The study of how melanoma cells manage to survive and proliferate by consuming glucose has been partially addressed in the literature, but some rather interesting results are starting to be present. Methods: A systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and a search of PubMed and Web of Sciences (WoS) databases was performed until 27 September 2021 using the terms: glucose transporter 1 and 3 and GLUT1/3 in combination with each of the following: melanoma, neoplasm and immunohistochemistry. Results: In total, 46 records were initially identified in the literature search, of which six were duplicates. After screening for eligibility and inclusion criteria, 16 publications were ultimately included. Conclusions: the results discussed regarding the role and expression of GLUT are still far from definitive, but further steps toward understanding and stopping this mechanism have, at least in part, been taken. New studies and new discoveries should lead to further clarification of some aspects since the various mechanisms of glucose uptake by neoplastic cells are not limited to the transporters of the GLUT family alone.

1. Introduction

Malignant melanoma is the most aggressive of skin cancers and the 19th most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated age-standardized incidence rate of 2.8–3.1 per 100,000 [1]. Although the advent of new targeted molecular therapies (directed against BRAF mutations) and immunotherapy have made it possible to improve the survival and clinical outcome of affected patients, even today the diagnosis of melanoma still has a strong impact on the patient’s life, and survival rates are strictly dependent on independent prognostic markers, above all, Breslow thickness [2,3]. In the diagnostics, staging, restaging and follow-up of patients suffering from various neoplasms, including melanoma, positron emission tomography/CT with the use of 18 fluoro-deoxy-glucose is considered the “gold standard” investigation [4]. The underlying physical principle relates to the notion that proliferating cells modify their glucose metabolism so as to allow them to “feed” through the process of aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect), surviving and maintaining the neoplastic clone in expansion [5]. Against this background, some works in the literature have shed some light on the potential relationships between glucose uptake, visualization in FDG-PET/CT and predominantly immunohistochemical expression of glucose transporters 1 and 3: that they have a high affinity for glucose and can operate in an insulin-independent manner. In this paper, we conduct a detailed review of the existing works in the literature on this topic, outlining the state of the art in this field and, finally, consider future viable paths.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A search of PubMed and Web of Sciences (WoS) databases was performed until 27 September 2021 using the terms: glucose transporter 1 and 3 and GLUT1/3 in combination with each of the following: melanoma, neoplasm and immunohistochemistry. Only articles in English were selected. Eligible articles were assessed according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 guidelines [6]. Review articles, meta-analyses, observational studies and letters to the editor were included. Other potentially relevant articles were identified by manually checking the references of the included literature.

An independent extraction of articles was performed by two investigators according to the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between the two review authors. Since the study designs, participants, treatment measures and reported outcomes varied markedly, we focused on describing the different approaches of the authors regarding the expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3 in malignant melanoma, analyzed the techniques (mainly immunohistochemistry) used in the works examined and, finally, analyzed the state of the art, imagining what the future perspectives may be.

3. Results

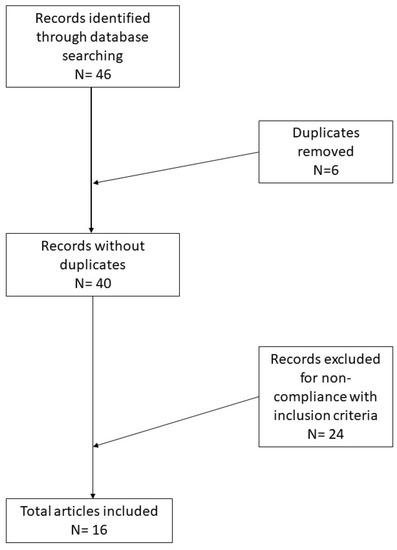

In total, 46 records were initially identified in the literature search, of which six were duplicates. After screening for eligibility and inclusion criteria, 16 publications were ultimately included (Figure 1). The study and features are summarized in Table 1. Most of the publications were original and/or research articles (n = 12), followed by reviews with or without metanalysis (n = 2), a comparative study (n = 1) and a case–control retrospective study (n = 1). All studies included were rated as level 4 or 5 evidence for clinical research as detailed in the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 guidelines [6].

Figure 1.

Research of the literature and selection of articles according to PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1.

Summary of the papers examined in this review.

4. Discussion

Melanoma continues to be the most aggressive cutaneous malignancy of all [1,23], featuring different incidence and prevalence rates on the various continents, but which tend to remain rather stable [23]. Classically, MM has always been distinguished as cutaneous or mucosal according to the site of onset, but, in recent years, research has made it possible to study in greater depth the mechanisms of the genetic–molecular landscape of both types, offering a better understanding of the points of contact and divergence [7,8]. It has long been known that glucose transporters (GLUT1-14) belong to the family of structurally related proteins that mediate the energy-independent transport of glucose across the plasma membrane. Among the various types, the most historically studied have been GLUT1, expressed mostly in erythrocytes, endothelial cells of the blood–brain barrier and placental cells and GLUT3, also present in various tissues [9,10]. Different works have shown that the basic principle on which the use of FDG-PET/CT is based is the increased energy requirement of cancer cells, with a consequent increase in the expression of GLUT1 and the neoplasm capacity to proliferate, survive and, finally, metastasize. This mechanism has been well studied and characterized in neoplasms of the breast, pancreas, cervix, endometrium, lung, mesothelium, colon, bladder, thyroid, bone, soft tissues and oral cavity [10,11,12]. Conversely, there are conflicting results regarding the role played by GLUT3 in various malignancies [13]. In the field of melanocytic pathology, we probed the role of GLUT1/3 in mediating glucose uptake and correlated findings with the clinical outcome.

In 2002, Wachsberger et al. demonstrated, by Western immunoblotting performed on 31 melanoma biopsies, a wide variability in the expression of both GLUT1 and HK and proposed the explanation that a broad spectrum of transporter activities could differently influence the response of patients to the same therapeutic treatment [14]. Three years later, Yamada et al. [15] conducted a study using four human melanoma cell lines (SK-MEL 23, SK-MEL 24 and G361) and one mouse (B16): the authors demonstrated that factors such as cell viability and rate of cell proliferation, as well as HK expression, were directly responsible for an increased glucose uptake at FDG-PET/CT. However, there did not appear to be any correlation between GLUT1 expression and the degree of glucose uptake. In another study, in 2008, Parente et al. reported results obtained from the analysis of 44 skin lesions, consisting of 12 benign nevi, 12 Spitz nevi and 20 primitive melanomas. The authors conducted an immunohistochemical study for markers such as GLUT1 and GLUT3 and reported that, unlike GLUT3 (expressed in all the lesions analyzed), GLUT1 was downregulated in 55% of primary melanomas, suggesting that glucose transport occurred across the plasma membrane by other transporters [16]. In 2009, Strobel et al. reported their experience with liver metastases resection samples from uveal and skin melanoma. Studying the reliability of FDG-PET/CT and the serum S-100B assay, the authors found that, while these determinations were reliable (sensitive) for skin-priming melanoma metastases, they were not as reliable in cases of metastasis from uveal melanoma [17]. In 2012, Park et al. conducted a detailed study to investigate the correlative association between glucose uptake in FDG-PET/CT, GLUT1/3 expression, exokinase-2 (HK-2) expression and Ki-67 expression in malignant melanoma. Enrolling 19 patients with a proven histological diagnosis of MM and pre-subjected to FDG-PET/CT, the authors found that the metabolic uptake increased with increasing GLUT1/3 expression, while HK-2 and Ki67 did not appear to be correlated [18,19,20]. Another important aspect was addressed by two other groups [21,24] regarding the role that hypoxia plays in the translocation and, therefore, expression of GLUT in cancer cells: from these works it emerged that the hypoxic condition is able to activate a pathway signal transduction mediated by HIF-1-alpha. In addition to other actions, this is able to promote the expression of glucose transporters, allowing the neoplastic cell to continue to survive through airborne glycolysis (Warburg effect) from oxidative phosphorylation. This has also been partially demonstrated in non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) [24].

In 2019, Dura et al. conducted a study of 400 cases (225 melanomas and 175 benign nevi) to evaluate the expression of GLUT1 in immunohistochemistry. They found that 69/225 melanomas were positive for this marker and, moreover, demonstrated an increasing expression (evaluated according to a semiquantitative score, Immunoscore 15) with increasing Breslow thickness. Intriguingly, the authors demonstrated that GLUT1 expression was correlated with shorter 10-year disease-free survival, relapse-free survival and shorter metastasis-free survival (MFS) [25]. Various other authors [22,26,27,28,29] have examined these aspects, sometimes with confirmatory but sometimes contradictory results. A very interesting recent paper by Reckzeh et al. described the discovery of a powerful inhibitor of glucose transporters 1 and 3, Glutor, that is capable of blocking the uptake of neoplastic cells, blocking the “metabolic plasticity” of cancer cells. Used together with a CB-839 glutaminase inhibitor, the combination can block cell proliferation and survival [30].

Importantly, a certain variability in the results obtained from immunohistochemistry for GLUT1-3 emerges from this revision of the literature. It is necessary to bear in mind that in immunoassays the binding between antibody and protein (GLUT) could be hindered by the phenomenon of the glycosylation of these receptors, following which they become more similar to glucose [31]. Finally, future research directions should take into account the different subcellular localization of GLUTs depending on the various isoforms and the various functional moments [32].

5. Conclusions

A better knowledge and closer study of the tumor phenotype have been for many years one of the most important targets in cancer research. The study of how the cancer cell is able to evade control mechanisms and apoptosis and proliferate has aroused great interest and attention. Against this background, various efforts have been made to better understand the metabolism of neoplastic cells, paying particular attention to the concept of “metabolic plasticity” and the Warburg effect. The results discussed regarding the role and expression of GLUT are still far from definitive, but further steps toward understanding and stopping this mechanism have, at least in part, been taken. New studies and new discoveries should lead to the further clarification of some aspects since the various mechanisms of glucose uptake by neoplastic cells are not limited to the transporters of the GLUT family alone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato), A.C. (Anna Colagrande) and L.L.; methodology, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato), A.C. (Antonietta Cimmino), E.B. and C.A.; software, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato) and T.L.; validation, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato), P.R., C.A., C.F. and G.I.; formal analysis, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato) and F.A.; investigation, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato); resources, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato), V.L. and G.C. (Gennaro Cormio); data curation, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato) and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato), A.C. (Anna Colagrande and Antonietta Cimmino), G.I., L.R. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, C.F. and L.L.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, G.C. (Gerardo Cazzato). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, Z.; Yousaf, N.; Larkin, J. Melanoma epidemiology, biology and prognosis. EJC Suppl. 2013, 11, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, L.E.; Shalin, S.C.; Tackett, A.J. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, O.; Miller, D.D.; Bhawan, J. Cutaneous malignant melanoma: Update on diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2014, 36, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macapinlac, H.A. FDG PET and PET/CT imaging in lymphoma and melanoma. Cancer J. 2004, 10, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ždralević, M.; Brand, A.; Di Ianni, L.; Dettmer, K.; Reinders, J.; Singer, K.; Peter, K.; Schnell, A.; Bruss, C.; Decking, S.M.; et al. Double genetic disruption of lactate dehydrogenases A and B is required to ablate the “Warburg effect” restricting tumor growth to oxidative metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15947–15961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Cazzato, G.; Arezzo, F.; Colagrande, A.; Cimmino, A.; Lettini, T.; Sablone, S.; Resta, L.; Ingravallo, G. “Animal-Type Melanoma/Pigmented Epithelioid Melanocytoma”: History and Features of a Controversial Entity. Dermatopathology 2021, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzato, G.; Colagrande, A.; Cimmino, A.; Caporusso, C.; Candance, P.M.V.; Trabucco, S.M.R.; Zingarelli, M.; Lorusso, A.; Marrone, M.; Stellacci, A.; et al. Urological Melanoma: A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Subclass of Mucosal Melanoma with Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approaches. Cancers 2021, 13, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Fukusato, T.; Nemoto, T.; Sekihara, H.; Seyama, Y.; Kubota, S. Coexpression of glucose transporter 1 and matrix metal-loproteinase-2 in human cancers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, Y. Expression of the human erythrocyte glucose transporter in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urology 2000, 55, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover-McKay, M.; Walsh, S.A.; Seftor, E.A.; Thomas, P.A.; Hendrix, M.J. Role for glucose transporter 1 protein in human breast cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 1998, 4, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, M.; Moergel, M.; Stockinger, M.; Jeong, J.H.; Fritz, G.; Lehr, H.A.; Whiteside, T.L. Overexpression of GLUT-1 is associated with resistance to radiotherapy and adverse prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Oral Oncol. 2007, 43, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Satoh, S.; Hayashi, H.; Inayama, Y.; Kitamura, H. Expression of facilitative glucose transporter isoforms in lung carcinomas: Its relation to histologic type, differentiation grade, and tumor stage. Mod. Pathol. 1998, 11, 437–443. [Google Scholar]

- Wachsberger, P.R.; Gressen, E.L.; Bhala, A.; Bobyock, S.B.; Storck, C.; Coss, R.A.; Berd, D.; Leeper, D.B. Variability in glucose transporter-1 levels and hexokinase activity in human melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2002, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Brink, I.; Bissé, E.; Epting, T.; Engelhardt, R. Factors influencing [F-18] 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (F-18 FDG) uptake in melanoma cells: The role of proliferation rate, viability, glucose transporter expression and hexokinase activity. J. Dermatol. 2005, 32, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, P.; Coli, A.; Massi, G.; Mangoni, A.; Fabrizi, M.M.; Bigotti, G. Immunohistochemical expression of the glucose transporters Glut-1 and Glut-3 in human malignant melanomas and benign melanocytic lesions. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, K.; Bode, B.; Dummer, R.; Veit-Haibach, P.; Fischer, D.R.; Imhof, L.; Goldinger, S.; Steinert, H.C.; von Schulthess, G.K. Limited value of 18F-FDG PET/CT and S-100B tumour marker in the detection of liver metastases from uveal melanoma compared to liver metastases from cutaneous melanoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.G.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, W.A.; Han, K.M. Biologic correlation between glucose transporters, hexokinase-II, Ki-67 and FDG uptake in malignant melanoma. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2012, 39, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airley, R.; Evans, A.; Mobasheri, A.; Hewitt, S.M. Glucose transporter Glut-1 is detectable in peri-necrotic regions in many human tumor types but not normal tissues: Study using tissue microarrays. Ann. Anat. 2010, 192, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, K.; Kastenberger, M.; Gottfried, E.; Hammerschmied, C.G.; Büttner, M.; Aigner, M.; Seliger, B.; Walter, B.; Schlösser, H.; Hartmann, A.; et al. Warburg phenotype in renal cell carcinoma: High expression of glucose-transporter 1 (GLUT-1) correlates with low CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the tumor. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 2085–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Kim, T.K.; Brożyna, A.A.; Janjetovic, Z.; Brooks, D.L.; Schwab, L.P.; Skobowiat, C.; Jóźwicki, W.; Seagroves, T.N. The role of melanogenesis in regulation of melanoma behavior: Melanogenesis leads to stimulation of HIF-1α expression and HIF-dependent attendant pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 563, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Gao, T.; Jiang, M.; Wu, L.; Zeng, W.; Zhao, S.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. CD147 silencing inhibits tumor growth by suppressing glucose transport in melanoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64778–64784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, N.H.; Li, W.Q.; Qureshi, A.A.; Weinstock, M.A.; Cho, E. Epidemiology of Melanoma. In Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy [Internet]; Ward, W.H., Farma, J.M., Eds.; Codon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2017; Chapter 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481862/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Seleit, I.; Bakry, O.A.; Al-Sharaky, D.R.; Ragab, R.A.A.; Al-Shiemy, S.A. Evaluation of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α and Glucose Transporter-1 Expression in Non Melanoma Skin Cancer: An Immunohistochemical Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, EC09–EC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Důra, M.; Němejcová, K.; Jakša, R.; Bártů, M.; Kodet, O.; Tichá, I.; Michálková, R.; Dundr, P. Expression of Glut-1 in Malignant Melanoma and Melanocytic Nevi: An Immunohistochemical Study of 400 Cases. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019, 25, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, K.N.; Liu, C.L.; Li, Z.; Felty, C.C.; Wells, W.A.; Yan, S. Diagnostic and prognostic value of glucose transporters in mela-nocytic lesions. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, K.J.; Choi, H.; Oh, H.R.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.B.; Jung, Y.J.; Koh, J.; Park, S.; Lee, H.J.; Jeon, Y.K.; et al. Reciprocal change in Glucose metabolism of Cancer and Immune Cells mediated by different Glucose Transporters predicts Immunotherapy response. Theranostics 2020, 10, 9579–9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.J.; Wienke, A.; Surov, A. Associations between GLUT expression and SUV values derived from FDG-PET in different tumors-A systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Lu, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.H.; Tang, J.H. Predictive value of glucose transporter-1 and glucose transporter-3 for survival of cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 13206–13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reckzeh, E.S.; Karageorgis, G.; Schwalfenberg, M.; Ceballos, J.; Nowacki, J.; Stroet, M.C.M.; Binici, A.; Knauer, L.; Brand, S.; Choidas, A.; et al. Inhibition of Glucose Transporters and Glutaminase Synergistically Impairs Tumor Cell Growth. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 1214–1228.e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Katagiri, H.; Takata, K.; Lin, J.L.; Ishihara, H.; Inukai, K.; Tsukuda, K.; Kikuchi, M.; Hirano, H.; Yazaki, Y.; et al. The role of N-glycosylation of GLUT1 for glucose transport activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 24632–24636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaßen, T.; Vardanyan, S.; Brosig, A.; Merz, H.; Ranjbar, M.; Kakkassery, V.; Grisanti, S.; Tura, A. Monosomy-3 Alters the Expression Profile of the Glucose Transporters GLUT1-3 in Uveal Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).