Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis

2.1. Sustainable Behaviour of Heritage Visitors

2.2. The Tourism Experience at Heritage Sites

2.3. Place Attachment at Heritage Sites

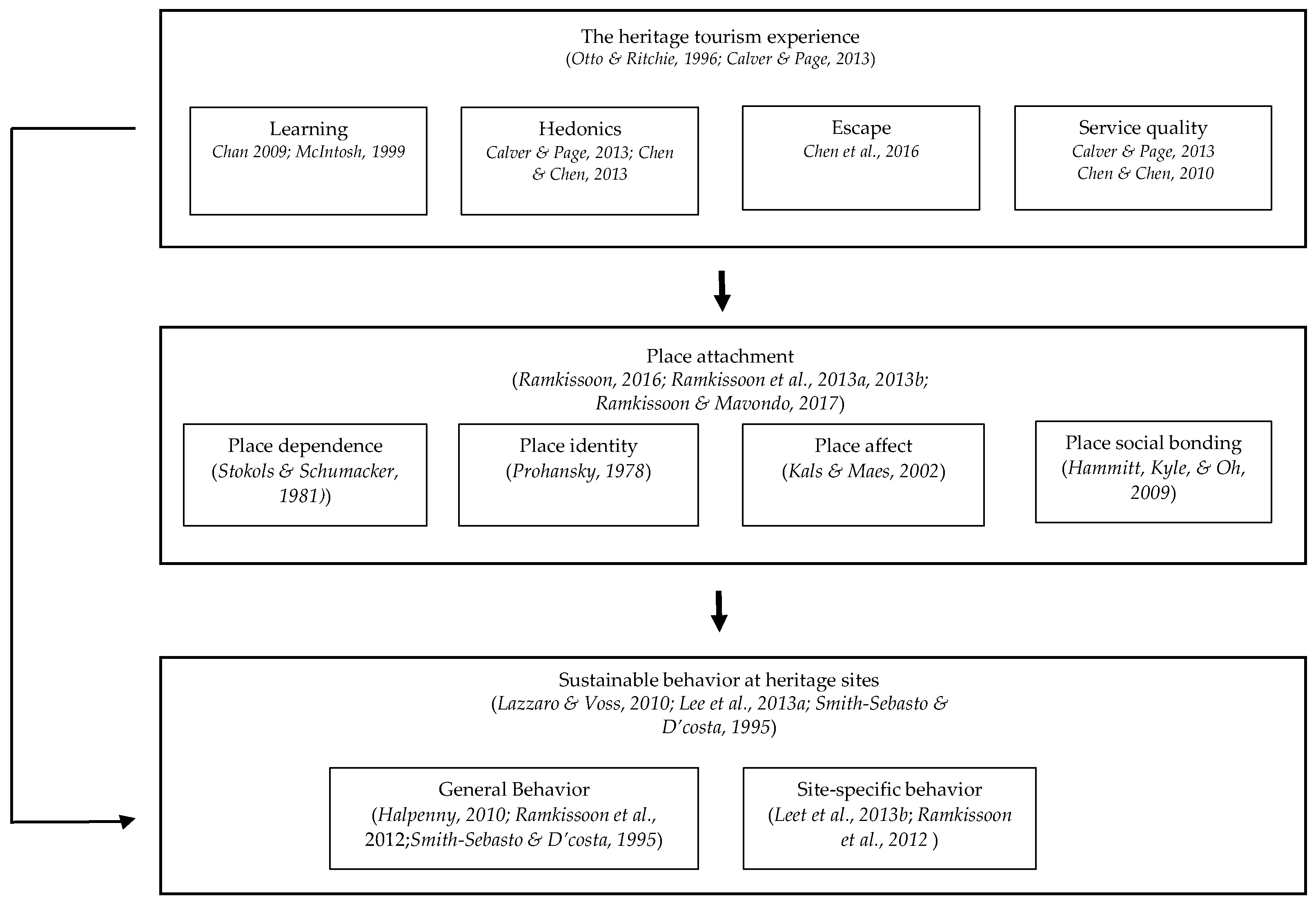

3. Development of a Conceptual Framework

3.1. Tourism Experience at Heritage Sites and Place Attachment

3.2. Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour of Heritage Visitors

3.3. Tourism Experience at Heritage Sites and Visitors’ Sustainable Heritage Behaviour

4. Scale Development and Model Testing

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Powell, R.B.; Ham, S.H. Can Ecotourism Interpretation Really Lead to Pro-Conservation Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour? Evidence from the Galapagos Islands. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardymana, N.; Burginbz, S. Nature tourism trends in Australia with reference to the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.; Adair, D. The growing recognition of sport tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. Pro-environmental Behavior: Critical Link Between Satisfaction and Place Attachment in Australia and Canada. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E. Parks and Carrying Capacity: Commons without Tragedy; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCooL, S.F.; Lime, D.W. Tourism carrying capacity: Tempting fantasy or useful reality? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R. Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alessa, L.; Bennett, S.M.; Kliskey, A.D. Effect of knowledge, personal attribution and perception of ecosystem health on depreciative behaviours in the intertidal zone of Pacific Rim National Park and Reserve. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 68, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Falk, J. Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: Testing short-and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modelling. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.L.; Green, J.D.; Reed, A. Interdependence with the environment: Commitment, interconnectedness, and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Doka, G.; Hofstetter, P.; Ranney, M.A. Ecological behavior and its environmental consequences: A life cycle assessment of a self-report measure. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cha, J.; Knutson, B.J.; Beck, J.A. Development and testing of the Consumer Experience Index (CEI). Manag. Serv. Qual. 2011, 21, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T.; Feng, S. Authenticity: The link between destination image and place attachment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M. Authenticity as a value co-creator of tourism experiences. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism; Prebensen, N., Uysal, M., Chen, J., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C.Y. What does UNESCO’s world heritage list mean for tourism? The endorsement effects of UNESCO’s world heritage designation on tourists’ pro-environmental, new tourism in the 21st century: Culture, the city, nature and spirituality. In Proceedings of the 1st EJTHR International Conference on Destination Branding, Heritage and Authenticity, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 21–22 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Environmentally responsible behavior of nature-based tourists: A review. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 2, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Durbarry, R. The Environmental Impacts of Tourism at the Casela Nature and Leisure Park, Mauritius. Int. J. Environ. Cult. Econ. Soc. Sustain. 2009, 5, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Mindful visitors: Heritage and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Authenticity, satisfaction, and place attachment: A conceptual framework for cultural tourism in African island economies. Dev. South. Afr. 2015, 32, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J. Into the Tourist’s Mind: Understanding the Value of the Heritage Experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1999, 8, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Sutherland, L.A. Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Place satisfaction, place attachment and quality of life: Development of a conceptual framework for island destinations. In Sustainable Island Tourism: Competitiveness and Quality of Life; Modica, P., Uysal, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2016; pp. 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Augmented Reality for Visitor Experiences; Visitor Management; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchini, E.; Santagata, W.; Signorello, G. Loving cultural heritage private individual giving and prosocial behavior. In Global Challenges Series; Ottaviano, G.I.P., Ed.; Fondazione ENI Enrico Mattei: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, E.; Voss, Z. Assessing citizens and visitors’ awareness, sharing of meaning and engagement in Dallas Public Art. In Proceedings of the ESA Research Network Sociology of Culture Midterm Conference: Culture and the Making of Worlds, Milano, Italy, 7–9 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Biran, A. Heritage site management: Motivations and expectations. Ann. Tourism. Res. 2006, 33, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage tourism in the 21st century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, L. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK; TPsychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, L. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S. Predicting residents’ pro-environmental behaviors at tourist sites: The role of awareness of disaster’s consequences, values, and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.R.; Volk, T.L. Changing learner behavior through environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Gill, J.D.; Taylor, J.R. Consumer/voter behavior in the passage of the Michigan container law. J. Mark. 1981, 45, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, L.J.; Lehman, D.R. Responding to environmental concerns: What factors guide individual action? J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green Issues: Dimensions of Environmental Concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.P.; Rose, R.L. The Effects of Environmental Concern on Environmentally Friendly Consumer Behavior: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Fostering customers’ pro-environmental behavior at a museum. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P. New Environmental Theories: Empathizing With Nature: The Effects of Perspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, M.H.; Stapel, D.A. RETRACTED: Me tomorrow, the others later: How perspective fit increases sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivek, D.J.; Hungerford, H. Predictors of responsible behavior in members of three Wisconsin conservation organizations. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.D.; Crosby, L.A.; Taylor, J.R. Ecological concern, attitudes, and social norms in voting behavior. Public Opin. Q. 1986, 50, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Ham, S.H.; Hughes, M. Picking up litter: An application of theory-based communication to influence tourist behaviour in protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G. A general measure of ecological behavior. J. App. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; D’Costa, A. Designing a Likert-Type scale to predict environmentally responsible behavior in undergraduate students: A multistep process. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture and Economy; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, D. Possessed by the Past: The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Theorizing Heritage. Ethnomusicology 1995, 39, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, G. Heritage: Pride or Passion, Product or Service? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2004, 10, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J. Heritage, identity and places: For tourists and host communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities; Singh, S., Timothy, D.J., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism; Pearson Education: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 32nd Session of the General Conference, Paris, France, 29 September–17 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and the personal heritage experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fyall, A. Heritage Tourism: A Question of Definition. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; White, D.D.; Woodrich, J.A.; Van Riper, C.J. Connecting Visitors to People and Place: Visitors’ Perceptions of Authenticity at Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. J. Herit. Tour. 2008, 3, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massara, F.; Severino, F. Psychological distance in the heritage experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism: Distinguishing heritage tourists from tourists in heritage places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Links between Tourists, Heritage, and Reasons for Visiting Heritage Sites. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Heritage of the Senses: Collective remembering as an embodied praxis. Tour. Stud. 2006, 6, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masberg, B.A.; Silverman, L.H. Visitor Experience at Heritage Sites: A Phenomenological Approach. J. Travel Res. 1996, 34, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.W.; Chen, M.C. A study of experience expectations of museum visitors. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Conceptualizing the experiences of heritage tourists: A case study of New Lanark World Heritage Village. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.C.; Witt, S.F.; Hamer, C. Tourism as experience: The case of heritage parks. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning; Altamira Press: Maryland, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.K.L. The consumption of museum service experiences: Benefits and value of museum experiences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis, A. Our Byzantine Heritage: Consumption of the past and its experiential benefits. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Coconstructing Heritage at the Gettysburg Storyscape. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 386–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Co-constructing the Narrative Experience: Staging and consuming the American Civil War at Gettysburg. J. Mark. Manag. 2008, 24, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J.M. “It’s supposed to be 1863, but it’s really not”: Inside the representation and communication of heritage at a pioneer village. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 21, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Tourists as Story-Builders: Narrative Construction at a Heritage Museum. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.; Brown, K. Relationship between destination image and behavioral intentions of tourists to consume cultural attractions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver, S.J.; Page, S.J. Enlightened hedonism: Exploring the relationship of service value, visitor knowledge and interest, to visitor enjoyment at heritage attractions. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.B. The service experience in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Another look at the heritage tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F. Heritage tourist experience, nostalgia, and behavioral intentions. Anatolia 2015, 26, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Bigham, G.; Zou, Z.; Hill, G. A global study of heritage site ecology, proclivity & loyalty. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2015, 25, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Gretzel, U. Effects of podcast tours on tourist experiences in a national park. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Sadness and Depression; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Leask, A.; Phou, S. Symbolic, Experiential and Functional Consumptions of Heritage Tourism Destinations: The Case of Angkor World Heritage Site, Cambodia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Pro-environmental behavior: The link between place attachment and place satisfaction. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Björk, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawke, S.K. Local residents exploring heritage in the North Pennines of England: Sense of place and social sustainability. Int. J. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E. Whose sense of place? Reconciling archaeological perspectives with community values: Cultural landscapes in England. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2005, 11, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.S.; Huang, H.Y.; Liu, W.C. Heritage, local communities and the safeguarding of ‘Spirit of Place’ in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place-Between the Tangible and the Intangible’, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vong, L.T.N. An investigation of the influence of heritage tourism on local people’s sense of place: The Macau youth’s experience. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Kneebone, S. Visitor satisfaction and place attachment in national parks. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W.; Jachna, T. The co-creation/place attachment nexus. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Sun, C.Y. Antecedents and consequences of place attachment. J. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 55, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Prohansky, H.M. The city and self-identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Maes, J. Sustainable development and emotions. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W., Eds.; Kluwer: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D.; Shumacker, S.A. People in places: A transactional view of settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior, and the Environment; Harvey, J., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Hammitt, W.E.; Kyle, G.T.; Oh, C.O. Comparison of place bonding models in recreation resource management. J. Leis. Res. 2009, 41, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Baumgartner, H.; Pieters, R. Goal-directed emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1998, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The norm activation model and theory-broadening: Individuals’ decision-making on environmentally-responsible convention attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H.; Gursoy, D. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: Past, present, and future. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. The development of indicators for sustainable tourism: Results of a Delphi survey of tourism researchers. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H.; Hunter, C.; Moore, B. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Tourism Development: Using the Delphi Technique. Tour. Manag. 1990, 11, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, E.; Macauley, J.A. The Delphi Technique in the Measurement of Tourism Market Potential: The case of Nova Scotia. Tour. Manag. 1984, 5, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, C.; Garrido, M.J.; Vicente, E. Achieving effective visitor orientation in European museums. Innovation versus custodial. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 16, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Terms | Definitions | Key Concepts | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmentally Responsible Behaviour | Actions motivated by the desire to interact with the environment in more responsible ways. Actions aimed at supporting a more sustainable use of natural resources, at mitigating a negative environmental impact of home and tourism activities, and at contributing to environmental preservation and/or conservation efforts. | Interaction | [17,35,45] |

| Environmentally Concerned Behaviour | The positive attitudes aimed at preserving the environment, also through indirect effects. | Commitment | [36,37,38,39,46] |

| Environmentally Significant Behaviour | Changes in the individual’s behaviour aimed at improving the environment. | Changes | [40] |

| Pro-environmental Behaviour | Behaviour exhibited by individuals who engage in actions to protect the environment and minimize any negative impact on the natural and built world. | Engagement Emphasis with nature | [40,41,42,43] |

| Sustainable Behaviour | A behaviour by individuals who act with more sustainable considerations. | Awareness | [44] |

| CONCEPT | Dimensions | References |

|---|---|---|

| General Behavior | Civil actions

| Adapted from [1,17,39,50] |

Educational actions

| Adapted from [1,50,51] | |

Financial actions

| Adapted from [1,16,17,27,39,50] | |

Persuasive actions

| Adapted from [17,39,50] | |

Legal actions

| Adapted from [17,50] | |

| Site-specific Behavior |

| Adapted from [17,27,28] |

| General Heritage Visitors’ Sustainable Behaviour |

|---|

| (1) I would be willing to pay much higher taxes in order to protect the cultural heritage. |

| (2) I am a member of one or more organisations concerned with the support and the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (3) In the last year, I have signed one or more petitions to support cultural heritage protection. |

| (4) In the future, I would be willing to sign one or more petitions to support cultural heritage protection. |

| (5) In the past, I have written one or more letters to government officials about the need of more cultural heritage protection. |

| (6) In the future, I would be willing to write one or more letters to government officials about the need of more cultural heritage protection. |

| (7) I have voted for elected officials that support cultural heritage protection. |

| (8) I insist on candidates who consider cultural heritage protection a priority. |

| (9) I usually donate money to organisations concerned with the protection and improvement of cultural heritage. |

| (10) I usually give time to support a pro-cultural heritage protection organization. |

| (11) I usually attend meetings in the community about the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (12) I usually read publications about the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (13) I usually watch TV programs about cultural heritage protection issues. |

| (14) I usually read books, publications and other material about cultural heritage problems. |

| (15) I am interested in learning how to solve issues related to cultural heritage protection. |

| (16) I avoid the use or purchase of certain products because of their negative impact on cultural heritage. |

| (17) I buy products from companies involved in the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (18) I buy products from firms that are careful to the history, traditions and identity of communities. |

| (19) I make a special effort to buy products related to the history and culture of local communities. |

| (20) I usually talk with others about the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (21) I usually talk with parents about the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (22) I promote the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (23) I promote the need to have a more responsible behaviour when visiting cultural heritage sites. |

| (24) I try to convince friends to act responsibly when visiting cultural heritage sites. |

| (25) I persuade others to adopt pro-heritage behaviours. |

| (26) I convince someone to visit less crowded heritage sites in order to protect and enhance cultural heritage. |

| (27) I convince someone not to visit crowded heritage sites in order to protect and enhance cultural heritage. |

| (28) I convince someone to buy products from firms that are careful or involved in the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (29) I convince someone to donate time or money for the protection of cultural heritage. |

| (30) I report someone who violates a law or laws that protect our cultural heritage to the proper authorities. |

| Site-Specific Heritage Visitors’ Sustainable Behaviour |

| (1) I have adopted a work of art at a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (2) In the future, I would be willing to adopt a work of art at a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (3) I usually join in community efforts dedicated to protect a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (4) I do volunteer work for a group that helps the protection of a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (5) I support the protection of a specific cultural heritage site with money. |

| (6) I have intention to donate money to a specific cultural heritage site for its protection. |

| (7) I would be willing to pay much higher entrance tickets to visit a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (8) I donate money to support a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (9) I think a good idea to protect a specific cultural heritage site is to limit the number of people who visit it. |

| (10) I think stricter mandatory regulations should be developed for visitors in an effort to minimize their negative impacts at a specific cultural heritage site. |

| (11) I think the scientific monitoring of the state of a specific cultural heritage site should be increased in order to ensure its protection. |

| (12) After visiting a specific cultural heritage site, I leave the place as it was before. |

| (13) I convince someone to respect the specific cultural heritage site they are visiting. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112

Buonincontri P, Marasco A, Ramkissoon H. Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2017; 9(7):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuonincontri, Piera, Alessandra Marasco, and Haywantee Ramkissoon. 2017. "Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 9, no. 7: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112