1. Introduction: Professional without Many of the Characteristics of a Profession

Much attention has been paid to rising professionalism across many occupations during the second half of the twentieth- and the beginning of the twenty-first centuries. Historically, the literature has tended to focus on the growth of applied professions (e.g., vocational disciplines, engineering, architecture) in addition to learned ones (e.g., law, medicine, theology), as well as on the evolution of various occupations into semi-, and sometimes fully sustainable professions. Much of the focus in the literature has been on the development of education/training preparation and gaining proficiency in specialized bodies of knowledge. The processes of organizational and field structuration have been another recurring theme in the literature [

1]. Technology has also played a crucial role in the distribution and availability of jobs. In the Oxford Martin School study, “The Future of Employment”, it was estimated that 47% of total U.S. jobs are susceptible to computerization and could be automated in the next 20 years [

2]. The study also anticipated that low-skill and low-wage workers would be reallocated to carry out tasks requiring “creative and social intelligence… and skills”, which are “non-susceptible to computerisation” [

2] (p. 269). We believe that creative and social intelligence and skills are especially common in cultural workers with artistic and entrepreneurial capacities. In addition, the form that professions in the creative sector take will be (and already are) very different from the ones that we regard as “professional” occupations.

Another stream of the professionalization literature deals with the growing phenomenon of highly educated and skilled workers who are engaged in multiple part-time and temporary jobs without clear career paths. These work-lives, shaped by artists’ pragmatic economic choices, are often characterized as freelancing, hybrid practices, and/or portfolio/protean (i.e., variable) careers [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, the practices denoted by these terms are markedly differently to the structuration processes usually associated with the trajectory of a professional career. This seems to suggest that portfolio practices and protean careers are incompatible with building and maintaining professional status. The contradiction is particularly apparent among artists and other cultural workers in the creative sector who work to sustain their art and lives by piecing together multiple sources of income.

In this article, we focus on the protean/portfolio career in the arts, analyzing the ways in which the arts sector offers a primary venue for cultivating artistic and entrepreneurial creativity. Our purpose is twofold: we document and analyze the multivalent ways successful cultural workers/artists professionalize their portfolio practices, through entrepreneurial self-management and self-structuration. Here, we contribute to scholarship on professionalization and the social practices of work by examining the emergence of a new enactment of professionalism in the growing “gig” economy. We also consider the disparate ways cultural workers/artists have found to build creatively satisfying and economically sustainable careers in the arts sector and offer our Integrated Model for Self-Structuring Portfolio Professions, in the hope of stimulating further scholarly discourse and analytical understanding of this social phenomenon. In the long-run, these insights may, in turn, inform current efforts to teach entrepreneurial skills and competencies to aspiring artists and other cultural workers, as well as help clarify the public perspective of the professional status and challenges faced by arts workers.

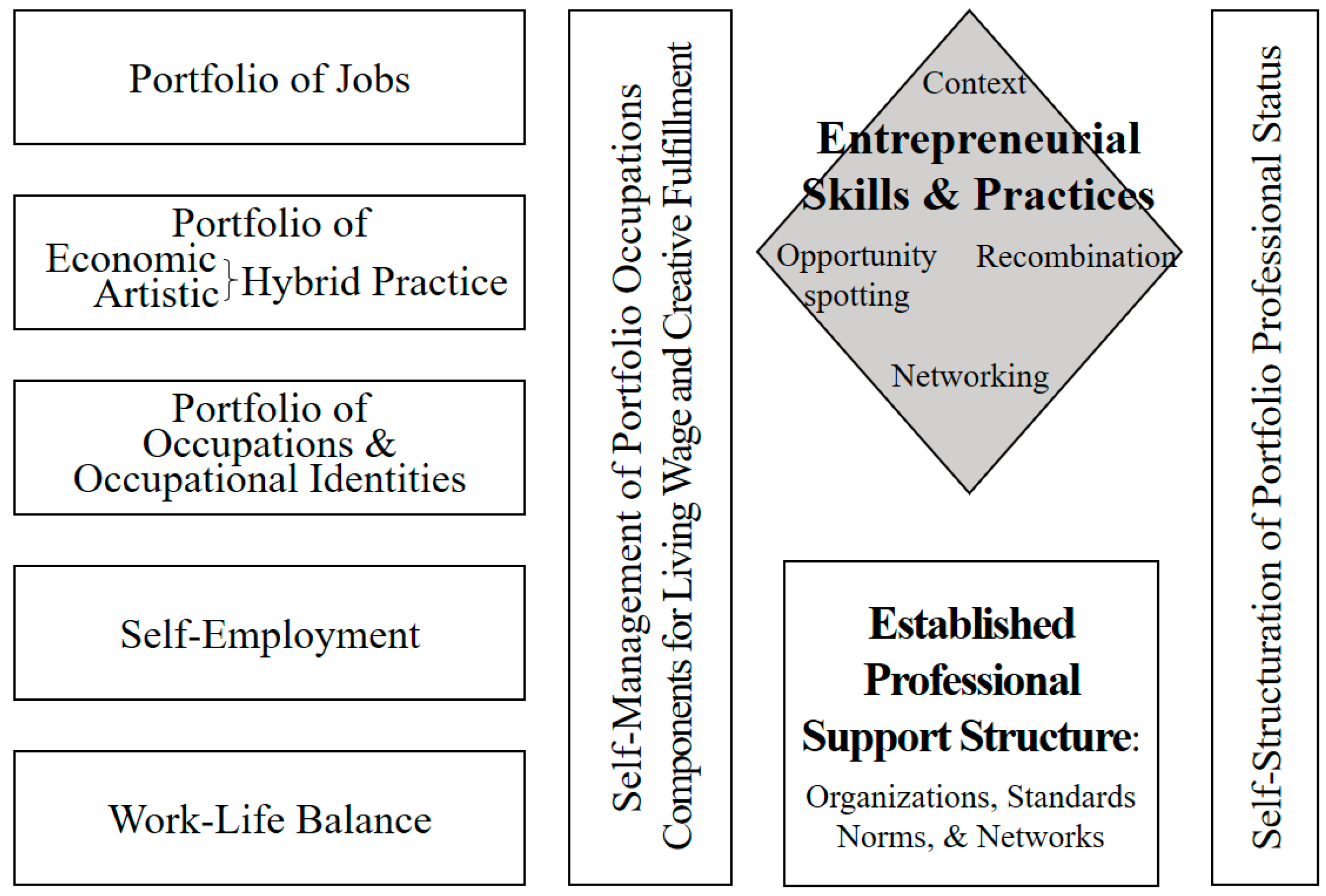

We begin by presenting a concept map of the Self-Structuration Model (

Figure 1). We deconstruct each term, identify how each highlights certain aspects of this complex and evolving phenomenon, and cluster related ideas into broader concepts. We take an integrative approach to reveal the relationships among the terms that characterize part-time work, stimulating further scholarly discourse regarding temporary jobs, to better understand how they reflect attempts to adapt principles of professionalism to changing economic conditions. We also explore the role of cultural policy in shaping recent developments in work practices and social status. We discuss how cultural workers combine career components through a process of arts entrepreneurship, namely career self-management. This process involves individual workers constructing their portfolio professions from the building blocks of numerous occupational resources, norms, skills, and competencies. We refer to this process as “self-structuration” which we distinguish from “self-management”; the former describes the creation of one’s personalized work life, while the latter describes the day-to-day management of that work life in order to sustain it.

We see the concept of self-structuration as lying at the intersection of multiple strands of the sociology of work, many of which provide insights into how institutions, routine patterns of social interaction, and individual agency interact to structure fields, organizations, and professions. These include Giddens’ theory of structuration and its attention to the role of worksites, both local and across multiple interrelated worksites, as well as the dynamics by which institutions are reproduced and altered [

16]. Our concept of self-structuration also builds on the artworld focus of Becker in revealing the ecology of working in the arts through everyday workplace settings and networks [

17]. Bourdieu’s concept of

habitus, which describes the ongoing interplay between objective structures and subjective individuals [

18] is useful for understanding the processes that shape an artist's disposition, or “trained capacities and structured propensities to think, feel and act in determinant ways” [

19] (p. 316), as a professional. In addition to these classic perspectives, we also note the more recent work of Jack and Anderson [

20] who build on Gidden’s theory of structuration to develop their concept of entrepreneurship as an embedded socio-economic process. Finally, we incorporate the thinking of DiMaggio and Powell [

21] concerning the role of self-aware and self-interested actors in the structuration of organizational fields—and, by extension, professions.

Because some regard a portfolio/protean career as contradictory to specialization and the development of a focused identity, they see it as counter to the conventional reliance on workplace organizations to reinforce norms that characterize professionalism. But in practice, individuals who are self-structuring their portfolio professions paint a more complex picture. Thus, we ask: how do cultural workers/artists in today’s social context create economically and creatively sustainable careers? What can we learn from their experiences about broader questions of the cultural value of art, the ongoing trend toward professionalization, and the changing roles of the worker and the entrepreneur in 21st- century economic life? To begin to answer these questions we examine some of the varied strategies creative artists have employed to build creatively satisfying and economically sustainable careers in the arts sector. We argue that cultural workers/artists engage in a process of self-structuration to construct professional personal identities, and draw on specific social and cultural resources, as they create portfolio/protean careers that exhibit key characteristics of professionalism and entrepreneurial self-management. Beyond identifying this emergent social phenomenon, we put forward our Integrated Model for Self-Structuring Portfolio Professions as both an analytical tool and a roadmap for arts entrepreneurship education. In this way, we contribute to broader discussions on arts entrepreneurship and professionalism in both the arts sector and academia.

2. Materials and Methods

To answer our research questions, we pursued three lines of inquiry: (1) a focused review of the research literature; (2) interviews and ongoing dialogues with creative professionals, along with our own pedagogical experiences with educating future arts sector cultural workers; and (3) a comparative concept analysis of the language and terminology that cultural worker/artists, scholars, policymakers, and arts organizations use to discuss professionalization and entrepreneurship in the arts.

We conducted a selective literature review of how each of the aforementioned terms have been used in scholarly and cultural policy literature to determine the defining attributes and common usage of each. We also identified significant antecedent terms that have enjoyed prior usage by artists. We then pursued additional insights into careers in the creative sector by exploring how the results of our analysis can be gained using the additional conceptual lenses of professionalism and entrepreneurial career self-structuration and self-management.

Our research also has a strong ethnographic component. We have been reading, thinking, and teaching about the subject of working in the creative industries and creative sector for more than ten years. We draw on numerous discussions and informal interviews with creative professionals in the arts sector as well as interviews that our students conducted, for a class assignment, with cultural workers regarding their careers. The interviews took place in Columbus, Ohio and Seattle, Washington from August 2012 to July 2016. We selected our respondents to constitute a diverse group including individuals who worked in many creative occupations and roles, and had varied work experiences in the arts sector. Less formal, though more numerous, discussions between the authors and important actors in the arts world have been ongoing since 2008, primarily in the context of PAR (Participatory Action Research). Finally, we supplemented these discussions with our various classroom experiences of interacting with students aspiring to careers as arts entrepreneurs in the creative sector.

To make sense of this body of information, we employed comparative concept analysis. The terms we selected for concept analysis have been grouped into three clusters: “Portfolio of jobs”, “Portfolio of hybrid practices”, and “Portfolio/Protean careers”. We used these cluster terms to discuss work patterns and practices of artists and other cultural workers in the creative sector. We also identify an ongoing self-motivation function—variously called freelancing, self-employment, or self-management—and link it to the entrepreneurial competencies required for success. Finally, we identify the professional support structures that are available to cultural workers to help them structure their own portfolio professions (see

Figure 1).

Comparative concept analysis is a process for examining the defining characteristics and underlying assumptions of an idea, as well as the words used to identify, describe, and cluster that idea. Along with content analysis, concept analysis is used in many disciplines and applied to many topics, including public health, aging, program evaluation, planning, and feminism [

22,

23,

24,

25]. It is also useful for analyzing how and (sometimes) why ideas and their associated terminology are dynamic, that is, change over time and respond to changing circumstances [

26]. We elected to use concept analysis because it is a key component of public policy analysis, with much research on how to define policy issues and problems and how to develop feasible, legitimated policy solutions. Comparative analysis of related concepts helps us to better understand the origins and antecedents, the multiple contributing perspectives, and the defining characteristics of ideas about arts entrepreneurship.

We modify and simplify Wilson’s [

25] long-established concept analysis procedure, extending it into a comparative analysis of related terms to develop an operational definition. We use this modified procedure to explore the conceptual relationships among the discursive elements we found through our research and to then construct a working theory of professional self-structuration in the arts, which we call the Integrated Model for Self-Structuring Portfolio Professions.

Figure 1 presents a concept map that draws upon the building blocks and their interactions. The building blocks include the terms used to discuss working in the creative sector and how these ideas have shifted over time in response to changing circumstances. The map will serve as a guide to readers for the discussion in the following sections.

3. Conceptual Framework for Careers in the Creative Sector

What is an appropriate conceptual framework for planning, preparing for, and finally pursuing and sustaining, one’s work life in the creative sector? Debate over this question has both a long history and an inconsistent and confusing discourse. Recently, the topic has been reexamined, prompted by significant changes in working conditions and public funding of artists, considering the range of occupations that comprise the creative industries, and larger forces that affect the general workforce, including demographic change, globalization, rapid technological change, and the emergence of what has been variously called the knowledge, new, or creative economy.

Historically, the work life of an artist, the core worker of the creative sector or, as Florida [

27] (p. 69) calls them, “the super-creative core of the creative class”, has been viewed as a skilled artisanal occupation, or as a vocation, a calling sometimes compared to entering the clergy. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics categorizes key artist occupations as “professional specialty work”. However, the work experience of 20th-century artists has commonly displayed an irregular, part-time, and temporary pattern, which indicates that artists often undertook day jobs (moonlighting) that had nothing to do with the arts, that they operated in a gig-based (or project-based) economy, and that they worked on a freelance basis, and were often self-employed (e.g., [

3]). Such practices of multiple jobs with low-paying wages made pursuing creative occupations risky and tenuous. Nonetheless, in the context of institutionalizing nonprofit arts production, distribution, and presentation through cultural policy over the last fifty years, the precarious economic status of artists was, to some degree, stabilized by establishing public patronage and commissioning support systems. Arts funding policy also gave structure and opportunity for other creative occupations to grow and become better established, especially those of arts educators, arts managers, and arts advocates. However, today, working in the arts places one on an unclear and uncertain career path that belies the norms of a sequenced succession of jobs, acquired skills, and other characteristics of conventional occupational careers. Career success has often been viewed as highly unpredictable and prone to a “star system” in which exceptional rewards and recognition seemed to accrue only to a lucky few. As Steven Dubin observed,

Artists are an enigma: they challenge many of the accepted notions of what it means to be members of a professional group in this society. On the one hand, they tend to undertake an extended period of formal training, maintain affiliations with professional organizations, and develop a strong sense of identification with their chosen field. On the other hand, they are subject to a number of highly contrasting trends. Their rates of unemployment and underemployment are marked, their income and the status they are accorded is low, and the degree of control and predictability they have over career lines is low relative to other professional groups.

Given the enigmatic status of “established” creative artists conducting sustainable work-lives in society and in the workplace, during the last fifty years, it has become increasingly common to regard them as “professionals” [

29] (p. 37). Twenty years ago, Jeffri and Throsby [

30] explored some of the inconsistencies in visual artists’ social and economic status. They concluded, that although professional visual artists possessed major hallmarks of professional standing, there was “still a lack of recognition by society at large of their social and cultural role, and an unwillingness to accord them the sort of respect as professionals that is shown to other professional groups” [

30] (p. 108). Even today, searching for generally recognized characteristics of professionalism still raises questions about the status of artists. The work life of artists seldom seems to manifest the key professionalism indicator of a high income and social status from fulltime activity at a task. For example, in 2012, the Future of Music Coalition conducted a survey of more than 5300 musicians to gather information about their work roles and income sources [

31]. They found that only 18% reported earning all of their income from one occupational type of activity (e.g., performer, composer, salaried player, recording artist, session player, teacher, and administrator). Even within this small group of one-occupation musicians, only a few worked full-time for one employer. Hence, the rarity of the fulltime employment that is expected in many other professions once again highlights the prevalence of freelancing and self-employment, in other words, creating a whole from many pieces [

31].

The many forms of work practice in the creative sector appear similar and are sometimes treated as though they were synonymous. This results in analytical confusion. First, a part-time job does not provide a living wage, but must be supplemented by other earnings. This is a common perception of working in the arts. A vocation is an inclination, as if in response to a calling, to undertake a certain kind of work. An occupation describes a relatively continuous pattern of activities that provide workers with a livelihood and define their general social status. The arts have often been regarded as a set of skilled occupations. A career refers to a succession of related occupations that are hierarchically arranged, through which a worker rises in an orderly sequence. Working in the arts has been viewed as lacking in both an orderly job sequence and hierarchical progression. Then there is a profession, which can be learned or applied. It includes a set of related occupations that require specialized knowledge and training, the development of relevant skills, formal means of ensuring competent and ethical conduct, and an ethos of service. It is also noteworthy, that the actual work patterns of artists and many other cultural workers across all of the work circumstances, are associated with a multiplicity and diversity of work products and processes, that are often suggested with various meanings of the term “portfolio” (see

Figure 1).

4. Portfolio of Jobs

A portfolio of jobs describes a work life model in which multiple part-time and/or temporary jobs and one-off gigs, take the place of a full-time and permanent job. Workers generate income from a combination of employers, as an alternative to a full-time job with a single employer. Such portfolios are increasingly common practice among millennials in general, as well as cultural workers/artists. Four terms commonly used to describe a portfolio of jobs are engaging in the “gig economy”, “freelancing”, “moonlighting”, and sometimes, working on “public grant projects” (see

Figure 2). In the arts sector, cultural workers/artists participate in the gig economy by doing different gigs or temporary jobs, each paid separately by different employers. In music, some of these short-term jobs are also known as “session” work, or “pick-up” ensembles. Freelancing involves working on different projects for different companies. Moonlighting is a form of holding multiple jobs, in which the artist’s job is defined as the “primary job” and where the worker commits the most hours. A second job or a “day job” sometimes refers to a job held outside the arts altogether (e.g., the proverbial actor who is a waiter, or the musician who is an Uber driver), or it can refer to another artistic job.

There is a large body of critical literature on the increased exploitation of creative workers in the “gig economy”, which records the sense of victimization and anger from workers in the creative/cultural industry, and analyzes this phenomenon in the larger context of globally shifting political economies of culture [

32,

33,

34,

35]. As Hesmondhalgh and Baker observe, “over the last twenty years... artistic (and informational) labor in the cultural and creative industries... has seen increasing casualization and short-term contract working”. For workers in these jobs, who tend to be younger, “work is irregular, contracts are shorter-term, and there is little job protection; career prospects are uncertain; earnings are very unequal” [

32] (p. 34). MacRobbie examines “small-scale entrepreneurial activities [in the] recent development of the creative economy in the UK” [

34]. These activities are not undertaken at the level of large organizations or companies, but rather, are undertaken in the cultural and creative sector by “both (upper) working class and (lower) middle class young people... who have, for a variety of both historical and social structural reasons” resisted being “interpellated more surely as subjects of state or institutional employment” [

34]. On the one hand, this “post-Fordist employment environment” affords young people the opportunity, as cultural workers, to be “more fully agents of their own employment destiny” [

34]. On the other hand, in becoming “individualized and disembodied from employment in large-scale social institutions”, which offered statutory protections, these young people are exposed to increased, and increasingly normalized, levels of precariousness and uncertainty. Thus, MacRobbie proposes that, for all the perks this emerging work–life model offers, it is in effect “an instrument of neo-liberal reform” that weakens employers' obligations to their employees, as it maximizes their access to a flexible, mobile, highly skilled workforce [

34].

As with the authors cited above and others, we too are mindful of the heightened potential for exploitative labor practices presented by the gig economy; however, our focus here is on understanding how individual cultural workers/artists negotiate the emergent creative economy.

Assembling a portfolio of jobs calls for managing time and effort to carry out a set of distinct tasks in order to sustain a stream of income, while also locating a continuing series of new jobs. Presenting data on the period between 1970 and 1997, Alper and Wassall [

3] reported that “artists were more likely to be multiple jobholders than their peers in other professional occupations” and that multiple jobholding rates showed consistent differences among different artistic occupations [

3] (p. 1). The primary reason for multiple jobholding was to meet household expenses [

3] (p. 7) rather than for creative satisfaction.

Working in the arts has long been described as a freelancing process of moving among gigs that are pieced together and often augmented by moonlighting in arts- or non-arts jobs. However, since the mid-1960s, with the establishment of public funding for the arts, another source of artist income has emerged for those who piece together a portfolio of jobs: public grants. These grants are a source of what might be analogous to unearned income for arts organizations. For some artists with freelance portfolios, another possible income source comes in the form of public grants, such as artist fellowships, public art commissions, and artist residency opportunities.

The amount of public grant funding available has never been sufficient to reach all artists or serve as a reliable source of income, thus, securing a public fellowship grant is a very competitive process. It came to be regarded as a reputation enhancing achievement that indicated that the grantee was held in high professional esteem by his/her peers. Hence, arts workers have tended to trade economic wages for psychic satisfaction, and have adjusted their portfolio of jobs to factor in an expanding nonprofit arts organization environment, that provides added job and employment opportunities, supported by funding from institutionalized philanthropy (private foundations and corporations). However, by the 1990s, the entire generation of artists and arts workers who had entered the workforce during the prime years of what John Kreidler [

36] has called the Ford era (1957–1990), began to discover their own changing expectations for sustaining a creative work life. They now added the nonprofit arts organization model and the growing availability of government funding for the arts to the conventional practices of the gig economy, freelancing, and moonlighting. Kreidler argued that the baby boom generation of arts workers (including artists, technicians, and administrators) showed a willingness to discount its wages because many were initially driven by their own desire to produce art, rather than by the prospects of public funding or hopes of economic gain [

36]. The capacity to sustain this self-motivation shifted as this generation of arts workers matured, and their life expectations drove them to hope that an arts career could bring adequate compensation, along with their growing professional status and family commitments. In other words, just as arts workers became less willing to discount their wages, the financial environment of the nonprofit arts sector experienced a decline in contributed revenue and a concomitant weakening of consumer demand. These developments made nonprofit arts organizations more reliant on discounted wages and less willing to increase the wages and employment of arts workers. When Congress prohibited the National Endowment for the Arts from awarding most artist fellowships in 1995, neither arts workers nor arts organizations had the willingness or capacity to continue the discounted wage arrangement of the Ford period. Thus, just as the establishment of public funding for the arts and for artists changed how an artist assembled his/her portfolio of jobs, the elimination of federal direct funding for artists helped to usher in further changes in the ecology of working in the arts.

By the mid-1990s, boundaries that were seen as characterizing the work lives of artists in the nonprofit arts, as distinct from those in the commercial arts or the informal arts, were not only changing in practice, but were also witnessing changes in policy definition both in the U.S. and abroad. Three seminal and virtually simultaneous policy developments in 1997 help us to bring these forces into focus. All three of these events enunciated the concept of the creative industries or the creative sector.

First, the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities (PCAH) issued a report, entitled

Creative America, that advocated for a fuller spectrum consideration of the arts, calling it “the cultural sector”. Noting that “in the United States, amateur, nonprofit and commercial creative enterprises all interact and influence each other constantly” [

37] (p. 2), the report contended that “the future vitality of American cultural life will depend on the capacity of our society to nourish amateur participation, to maintain a healthy nonprofit sector, and to encourage innovation in commercial creative industries”. A second key report,

The Arts and the Public Purpose [

38], emerged from American Assembly, a nonpartisan convener on issues of important national policy that had a track record of helping to shape and advance cultural policy definition since the late 1960s. It reflected the thinking of a group of public and private arts community leaders and researchers. While building on a similar sectoral perspective of an arts spectrum—consisting of commercial, nonprofit, volunteer, folk, amateur, and professional—the American Assembly report was aimed directly at reconceptualizing the public purposes of the arts, and how the sector’s capacity for public service could “help artists and artistic enterprise both to meet public purposes and to flourish” [

38] (p. 7). The third relevant policy event illustrates how this policy reconceptualization was both reflecting and driving different ways to think about the arts economy, and therefore, about cultural workers in general. This was the launching of the creative industries initiative in the UK and the publication of its groundbreaking Mapping Reports (see [

39,

40]). Eventually, the British research and policy development initiatives concerning the creative industries would give rise to the concept of portfolio careers that would span the creative sector. The fact that these policy reconceptualizations were not limited to the United States suggested that broader forces of economic change and globalization were beginning to prompt a rethinking of the place of the arts, in what some would call the “creative economy” and with that, a rethinking of the career patterns and prospects of cultural workers.

As arts communities and the arts policy community grappled with how such meta-changes did and might impact the work patterns and practices of creative workers, a plethora of new terms (and concepts) arose, while other longstanding terms and ideas were re-examined and re-purposed. While policy tried to redefine the arts more broadly, other components of the artist patronage system, particularly private foundations, turned new attention to how they might refashion the support system for artists in the nonprofit arts and address the resource gap that resulted from decreases in federal funding. The following foundation responses and initiatives are of particular relevance to our reconceptualization of working in the arts. The first response saw the organization of a consortium of foundations which underwrote the establishment, in 1999, of an artist funding organization called “Creative Capital”. This organization pooled private funds to create a new grant support program for artists; it went on to develop a companion program of peer mentoring and technical advice that would support the long creative process. By connecting innovative ideas and artistic creativity with incubator-like services and money from venture capital, this initiative helped artists take their ideas into the field and to their audiences [

13].

A second (and largely simultaneous) response from foundations was illustrated by a spinoff project of the James Irvine Foundation in California. In 2001, Cora Mirikitani, the Senior Program Director of the Irvine Foundation’s Arts Program and Innovation Fund, left the Foundation to launch a new organization aimed at fostering artist careers through a different investment strategy. In 2002, the Center for Cultural Innovation (CCI), which Mirikitani [

41] described as “a knowledge and financial services incubator for individual artists”, used seed funding from the Small Business Administration to launch a series of business training workshops for individual artists in Los Angeles. After at least four years of developing and offering this series, the CCI asked a number of the founding trainers to write essays for a workbook and resource guide that distilled the learning and information of the series. In 2008, these became the foundations for

Business of Art: An Artist’s Guide to Profitable Self-Employment, which CCI published. A second edition was released in 2012.

These foundation responses and initiatives (and their followers) illustrate a new self-management strategy for propelling professional work lives of creative artists. This strategy focused on providing opportunities for artists to acquire new business skills that they could use to secure and juggle multiple, temporary jobs in order to foster more sustaining freelancing portfolios. Eventually such discussions prompted concern about the education of artists (and other creative professionals), and whether or not they were being trained in a way that fully prepared them for the work–life demands they would face. Increasingly, a quality education for artists came to encompass, not only artistic knowledge, technique and history, but also some components of business know-how, technical as well as teaching skills, and general competencies such as problem solving, teamwork, critical thinking, and creative/innovative thinking (e.g., [

42,

43]).

Certainly, we cannot ignore that as this model—a portfolio of jobs—becomes more widespread in the creative industries, it may become a general driver, pushing more and more workers to become “entrepreneurs” who self-structure their careers. While career entrepreneurship offers the positive benefits of increased worker flexibility and agency, we cannot ignore its concurrent negative outcome in coupling increasing precariousness with decreasing security, and creating cultural work places sustained only by sacrificial labor, market overexposure, and self-exploitation, which are, as Ross [

44] found, still defining the on-the-job characteristics of the cultural industries.

6. Portfolio of Occupations

A protean—i.e., variable—career refers to a portfolio of occupations and occupational identities. This new form of career focuses on multiple personal motivations to construct one’s own career portfolio. Douglas Hall, Professor of Management at Boston University, coined the term in 1976 when he first applied the adjective “protean” to describe a new career style [

50]. He viewed it as the career of the 21st-century, distinguished by the fact that it is not driven by any organization, but is designed and conducted by each individual who chooses it—that is, it is individualized to meet one’s needs. He anticipated that the new form would be “reinvented by the person from time to time, as the person and the environment change” [

50] (p. 8). This career style is mostly about the process of self-structuration. The term “portfolio/protean career” is characterized by a personal construction of a career and recurrent acquisition or creation of work (likely to occur on a freelance or self-employment basis). It carries strong intrinsic motivations for, and personal identification with, career, and it blurs the boundaries between work and personal life. The intelligence skills needed for the protean career are well developed entrepreneurial skills (spotting creation of opportunities for marketing and selling of one’s art, recombination of one’s available resources, and self-management), and highly developed skills associated with arts practice (the generation of one’s art). The concept of a portfolio/protean career emphasizes the agency of the creative worker in the personal construction of his or her career [

4,

5,

6].

The idea of a portfolio career in the arts appears to have emerged initially in the UK as a natural outgrowth of the creative industries discourse, which expanded the range of work options for artists and other cultural workers in the creative sector. In contrast, the idea of a protean career developed outside the creative industries and notably included the work–life balance factor, in addition to multiple occupational categories, hybrid practices and self-employment responsibilities. Protean career theory calls for the integration of many occupational identities into a self-constructed meta-career identity. According to Greenhaus and Callanan [

11] and Briscoe et al. [

7], its central characteristic is that it is a reflection and manifestation of the individual career actor. It is thought to put self-fulfillment and psychological success above career norms that would have their source outside of the individual. It is a reflection and manifestation of the goal and concerns of the individual career actor who exercises work–life agency in individualizing his/her career self-management [

15]. The ideas of a portfolio/protean career intersected with the “boundaryless career concept” [

11,

15,

51], which emphasized an open range of career forms, found both within and across organizations, rather than primarily by the career system supported by a particular organization, or industry of organizations. The protean career connects to arts entrepreneurship as career self-structuration and self-management—that is, entrepreneurship as recombination, where moneymaking is only one of two drivers. This type of career reflects a quest for personal creative satisfaction and professional validation, in addition to economic success.

Thus, following Hall, a number of scholars have focused on the protean career attitude toward what it means to be successful in one’s work life. The “protean career” can be recognized by a certain attitude that an individual assumes in approaching his or her career. This attitude includes being proactive and self-directed, and judging one’s success or failure by one’s own values and criteria [

52,

53]. As De Vos and Soens [

9] note, individuals who assume a protean career have reported that they feel more satisfied in their careers and perceive themselves to be more employable. Their results support the idea that the protean career attitude is important for individuals in the current job market landscape where the focus is more on “security in ongoing employability rather than security in ongoing employment” [

5] (p. 40). Counterintuitively, research also supports that the attitude associated with the protean career does not negatively affect an individual’s commitment to an organization [

54].

The concept of the protean career, with specific focus on the arts sector, was perhaps first examined in Bridgstock’s 2005 article, “Australian artists, starving and well-nourished: What can we learn from the prototypical protean career?” Bridgstock analyzed Australian professional fine artists, performing artists and musicians’ employment/career data. She found that they fit the “new careerist” model, which makes them an ideal group for studying the protean career in future research. She also emphasized the career meta-competencies and career/life management skills essential for sustaining oneself in the world of boundaryless work [

5]. In 2010, the Australian Council for the Arts published a report titled,

What’s your other job? [

8]. Examining Australian Census data on employment patterns in arts industries, the report found that total employment numbers in artist occupations initially rose significantly, and occupations related to the arts grew even more, nearly doubling in size. In short, since 1996, most of the growth in arts employment in Australia has been mainly in arts-related occupations [

8]. This might suggest conditions ripe for the development of a portfolio/protean career consisting of multiple occupations and occupational identities involving various combinations of artists, educators, and managers, both within and outside the arts industries.

The 2003

Investing in Creativity report [

49] identified six key features of the support system for creative artists at both national and local levels: (1) Validation, (2) Demand/Markets, (3) Material Supports, (4) Training and Professional Development, (5) Communities and Networks, and (6) Information. It is noteworthy that these support systems are generally presumed to have been developed as part of the process by which occupations mature into professions. Identifying and exploring these six key elements was another way of expanding the conversation about improving the work life of artists, by acknowledging the wider and more diverse set of support systems and cultural workers involved in this ecology. As such, this report could be regarded as a commentary on the extent to which the work life of professional artists had (and had not) professionalized. This ecology might have helped broaden the awareness of other types of creative occupations that could be included in the portfolio/protean careers, especially those arts intermediaries that commonly work in the infrastructure of the creative sector (such as artist agents, arts critics, professional association administrators, arts advocate, etc. [

47] (p. 14)).

Figure 5 provides an example of a career constructed from multiple occupations, all of which are related to the music field. Such a career acquires the meta identity of a music professional who has functioned as an entrepreneurial manager of numerous careers in music. Each of the music-related occupations were situated within an established occupation that crossed various organizational and economic contexts in the creative sector. The cultural worker calls upon key entrepreneurial competencies, such as spotting or creating opportunities, recombining available resources, and adjusting to varying contexts, in order to construct a portfolio career. In addition, the careerist can draw upon the professional support resources of norms, standards, and networks associated with individual occupations to accomplish the self-structuration of a professional identity. We should also note that the literature and policy have developed a case for how artists contribute to the public interest [

49] (p. 3). The public interest can be served by an art teacher who helps students develop their creative and critical thinking skills; by an artist who acts as a catalyst for civic engagement or as a key player in creating culturally and economically vital places; and by an arts administrator who contributes to the transmission of group identities. Such examples of public service ethos provide an important missing ingredient of professionalism in the arts.

7. Assembling Self-Structuring Careers in the Arts and Creative Sector

This article has compared the three major concept clusters concerning working in the arts or the creative sector, and related these to ideas about arts entrepreneurship and professionalism in the arts. We have argued that a plethora of terms, and the variety of models they describe, in actuality, present a consistent theme and a cohesive model. In essence, a living wage and professional status in the arts does not necessarily come in a “package” that looks like other “classic” professions, which are primarily structured by organizations that employ traditional professional workers. Consequently, cultural workers/artists must develop ways to assemble portfolio professions that can sustain them economically, artistically, socially, and personally through the application of entrepreneurial skills, and by drawing on occupationally associated professional support structures.

Artists and other cultural professionals can tap into supporting structures available in various locations and forms in the creative/cultural sector. These entities provide services, information, advocacy, networks, and mechanisms for establishing and enforcing standards and norms that, for conventional professions, are provided through professional associations. Three common ways these support structures are built and supported include (1) artist-organized self-help activities and organizations; (2) networks for professional development and information services established through public arts agencies; and (3) foundation support for the creation and maintenance of artist support structures.

A good example of a national-level, artist-organized professional support structure is the Future of Music Coalition (FMC) [

55]. Founded in 2000 by a group of musicians, artist advocates, technologists, and legal experts, FMC “works to ensure that musicians have a voice in the issues that affect their livelihood”. FMC pursues its mission through education, research, and advocacy activities for musicians, focusing on issues at the intersection of music, technology, law, and intellectual property. With financial support from private foundations and donations from artists and other interested individuals, FMC organizes activities often provided by professional membership associations. Membership to FMC is free. FMC conducts networking events, including an annual policy summit, both paid and free workshops, and informational public panel discussions, a periodic newsletter to subscribers; they also maintain a roster of relevant panels and workshops held by other organizations [

56].

FMC’s annual policy summit brings together, musicians, artists, music industry leaders, technologists, arts and technology advocates, members of Congress, and officials of relevant federal agencies, foundation officers, and creative industry researchers, to discuss policy issues and political developments of mutual interest. The summit is usually held on a university campus, often in the Washington DC area, such as George Washington University and/or Georgetown University. FMC partners with other organizations to sponsor public discussions, such as the 4 November 2014 free panel on “Technology and the Entrepreneur: The Ever-Evolving Landscape of the Music Industry” which was part of the Library of Congress Fall Counterpoints series, presented in cooperation with the American Folklife Center. Another free panel discussion was held at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, “Metadata for Musicians”, to discuss proper metadata management in the process of releasing new music on digital platforms. FMC also presents paid workshops such as the two-day, “The Business of Music: Entrepreneurial Training for Musicians”, in June 2014, in partnership with the Center for Cultural Innovation and held at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center in Los Angeles, California.

An example of how FMC participates in and represents working musicians can be seen in the South by Southwest Festival (SXSW), which is a major international music and music business festival held annually in Austin, Texas. At the 2014 SXSW, FMC presented a collection of 14 panels, presentations, and public talks addressing subjects such as artist health care needs and how they were impacted by the Affordable Care Act and calls to reform it. There were also panels on intellectual property concerns, such as copyright enforcement and online music licensing; and music business skills and approaches such as making a “elevator business pitch” and learning how to think like an entrepreneur. They also presented a world premiere screening of the music-film “Pulp”, which follows the band Pulp’s final concert in Sheffield, UK along with career reflections and a career-best performance in their final UK concert.

Key advocacy issues that FMC follows include Internet broadcasting and digital radio with regard to musician royalties; internet neutrality and the ability of musicians and other creative entrepreneurs to reach audiences; copyright, piracy and musician compensation; health care and health insurance for independent artists and musicians. FMC also undertakes research that both documents the implications of key advocacy issues, and also informs musicians about the state of their profession. FMC not only surveys its members about the proportion of artists who lack health insurance to help demonstrate the need and impact of healthcare reform on its members but also developed HINT—the Health Insurance Navigation Tool—an interactive and personalized source of advice from health insurance experts who are also musicians. Another major research project of FMC is “42 Revenue Streams” that identifies this multiplicity of ways in which musicians can make money, details what percentage of income is likely to be derived from each stream and how these patterns differ for artists working in different genres and at different stages of their careers. Such comparative earning information is frequently a service of other, more institutionalized creative occupations including orchestra musicians and managers, other performing arts managers as well as museum staff.

Another example of an artist-organized support structure that has grown to operate on an international level is the Artist Pension Trust (APT) [

57]. This functions as a mutual assurance society for visual artists in which each participating artist deposits works of their art into an investment collection with other artists in a plan designed to amass pension benefits from the long-term appreciation of their artworks while sharing the financial risks with other artists [

58]. The APT handles storage, transportation, and insurance costs for maintaining the collection while also maximizing exposure and reputation building for its member artists. Today, APT has the largest global collection of contemporary art, comprised of nearly 13,000 artworks from 2000 artists in 75 countries. Artists are invited to join APT following a curatorial review. Participating artists agree to deposit, on average, one work of art every year, for twenty-years. What started as a financial security product, has evolved into “a kind of artist cooperative” that provides services, artist promotion as well as loan and exhibition services, in addition to the promise of eventual pension distributions. As one participating artist noted, the ultimate goal might be financial security for the future, but in the meantime, APT is providing “the networking and the support structure for the now” [

58].

A second source of professional support structure is provided by public cultural agencies at the local state, and regional level. While such arts agencies are well known as an important source of financial support through grants, they also provide many education, information, and networking resources for independent artists. For example, professional associations provide their members with information about job opportunities, conferences and other convenings. Most local and state arts agencies provide free listings, not only of job opportunities for artists, but also calls for entry to participate in arts fairs, craft festivals, and performing arts festivals, as well as call-for-proposals for public art commission [

59,

60]. They also publish a visual registry of artwork by local artists [

61]. Many local and state arts agencies public directories of qualified teachers, which schools use to identify visiting artists and artists to hire for in-school programs. These public arts agencies also offer professional development workshops that often address the need to acquire management skills, such as marketing, how to price one’s artwork or how to secure corporate sponsorships, as well as grant workshops to help artists write successful grants proposals. Sometimes public arts agencies work with the Small Business Administration to offer information and training sessions for artists who are essentially operating as small arts businesses. Public arts agencies and local chapters of Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts, offer informational program, clinics, and one-on-one advice on issues concerning contracts, intellectual property and copyright issues, and, on occasion, freedom of expression and censorship challenges. A number of state and regional arts agencies also organize talent showcases that bring together artists, arts ensembles and arts organizations with presenters and booking agents.

Local arts agencies (many of which are private nonprofit organizations rather than public agencies) act as public advocates for artists and their interests. In some communities, separate artist advocacy organizations exist, in addition to the local arts agency, for example, the Creative Alliance of New Orleans (CANO) [

62], for performing, design, media, literary, and culinary artists. Its mission is to provide education, training, and information for creative artists, cultural producers and the community, protect their shared cultural legacy, and promote city revitalization as a cultural and economic center. CANO also manages a variety of creative spaces in its efforts to support and present the work of creative artists, especially artists in underserved communities. Its Creative Futures program works with high school students to discover creative education and job opportunities, and a Career Technology Education certification program, to prepare students for jobs in growing creative industries. Like other such professional support structures, CANO often works through a number of partnerships. One of these joint activities is the annual Creative Industries Day in New Orleans, which CANO co-sponsors with the Louisiana Cultural Economy Foundation and the Downtown Development District. Creative Industries Day is part of the larger

New Orleans Entrepreneur Week. A highlight of Creative Industries Day is the “Downtown NOLA Arts and Business Pitch” where five arts business entrepreneurs compete for a prize package valued at

$40,000.

As many of the above examples demonstrate, private foundations often play a significant role in helping to financially support the development and maintenance of alternative professional support structures for independent artists. For example, in the case of the Future of Music Coalition, a major portion of its operating revenue comes from foundation grants. FMC’s last available Annual Report showed that six-sevenths of its total revenues came from Foundation grants [

56] (p.16), among the contributing foundations were major private foundations, such as the Mellon Foundation the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, and the Doris Duke Foundation.

Thus, we can see that part of the challenge of self-structuring portfolio professions comes from the need for mutual benefit mobilization and networking among artists and other creative workers, to form the necessary support structures that are not available in an institutionalized, national professional association. Some of these are provided through state, local or regional public arts agencies that regard the provision of various professional resources to artists to be part of their mission. However, this results in a fragmented and uneven distribution of the support structures from one location to another. It also imposes search costs on independent artists to identify where such structural pieces are available to them. Finally, we can also see that private foundations play an important role in supporting both the mutual benefit efforts of artists themselves as well as the public agency provision of extra financial support services. Both the creation of such self-structuration building blocks seems to be increasing, and the knowledge and experience of artists in establishing such supporting structures seems to be growing. But the information costs of assembling these building blocks of professional structuration remains a challenge.

Figure 6 below illustrates a model of how the preceding concepts can be integrated into a cohesive understanding of the development and sustainability of careers in the arts.

The starting point is the individual’s drive and desire to be a creative artist and/or cultural worker; aspiring artists must have a high level of belief in their talent and ability to succeed. The next step is to pursue, either formally or informally, the necessary specialized training and skills. It is important for the artist to simultaneously develop entrepreneurial skills so that they can pursue multiple occupational components in the cultural sector. Once the artist enters the cultural workforce they will be selecting and combining multiple components to develop and increase their professional skills and value in the workforce. Finessing the art of balancing these multiple pieces of a portfolio career simultaneously increases the chances of professional success. Also critical to an artist’s success is networking and strengthening their relationships with professional support structures, such as professional organizations, public arts agencies, advocacy initiatives, arts service organizations, etc. The important common denominator underlying all the varied forms that a portfolio/protean career takes, is the balance between artistic/creative training, on the one hand, and the development of entrepreneurial skills and know-how, on the other. As demonstrated in the integrated model (

Figure 6), incomes and work practices tend to be clustered into portfolios—of jobs, of hybrid practices, of occupations and of professional identities—that are self-structured by individual creative workers acting as the entrepreneurs of their own career management and sustainability.