User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Tourism Events, Social Media and User Empowerment

2.2. Social Media Based on Photographs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measures, Metrics and Methods to Assess Social Media Contributions

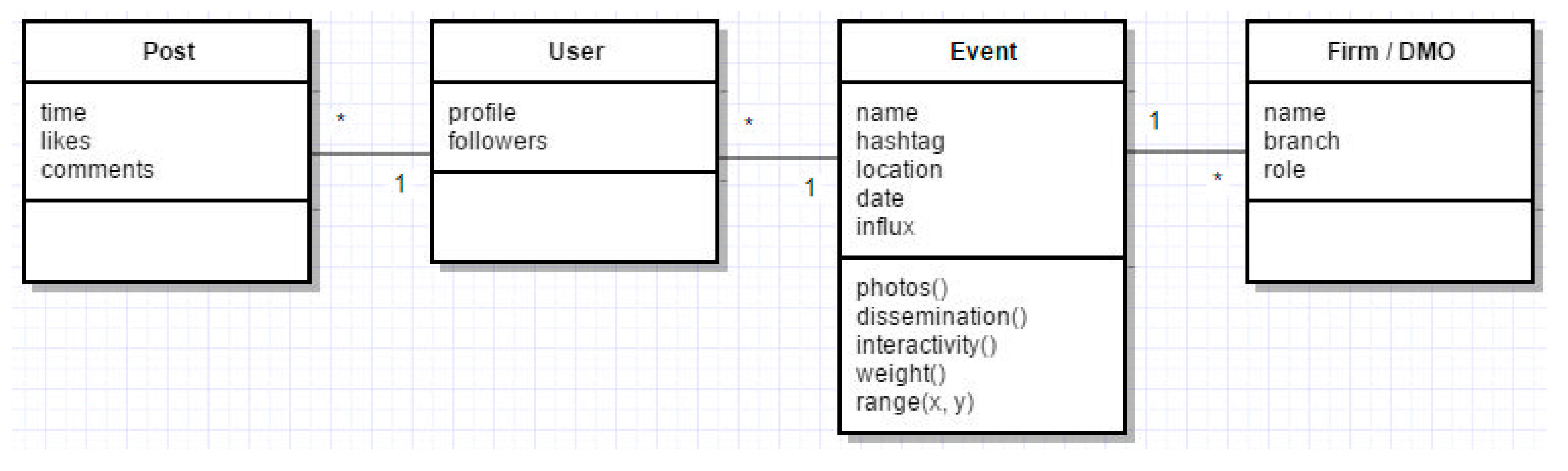

3.2. Object-Oriented Framework

- photos(): This method calculates the total number of pictures that have been submitted with the corresponding hashtags.

- dissemination(): This method calculates the quantity of potential Instagrammers who have received the pictures in first instance, by adding up the followers of users.

- interactivity(): This method calculates the quantity of reactions (likes and comments) that users’ posts had.

- weight(): This method calculates the growth in percentage that the number of user participants represents over the average visitors (influx attribute) in the area and season when there is no special event. This enables the comparison of the impact of events in different areas and/or dates.

- range(x, y): This is a parameterized method that enables the calculation of different types of ranges such as posts per user (to detect the most active users), followers per user (to detect their role as ‘influencers’), likes per post and comments per post (to detect the most engaging posts). Ranges are calculated in percentage to compare events with different numbers of participants.

3.3. Participant Observation

3.4. Case Study: Instagram Meetups

4. Results

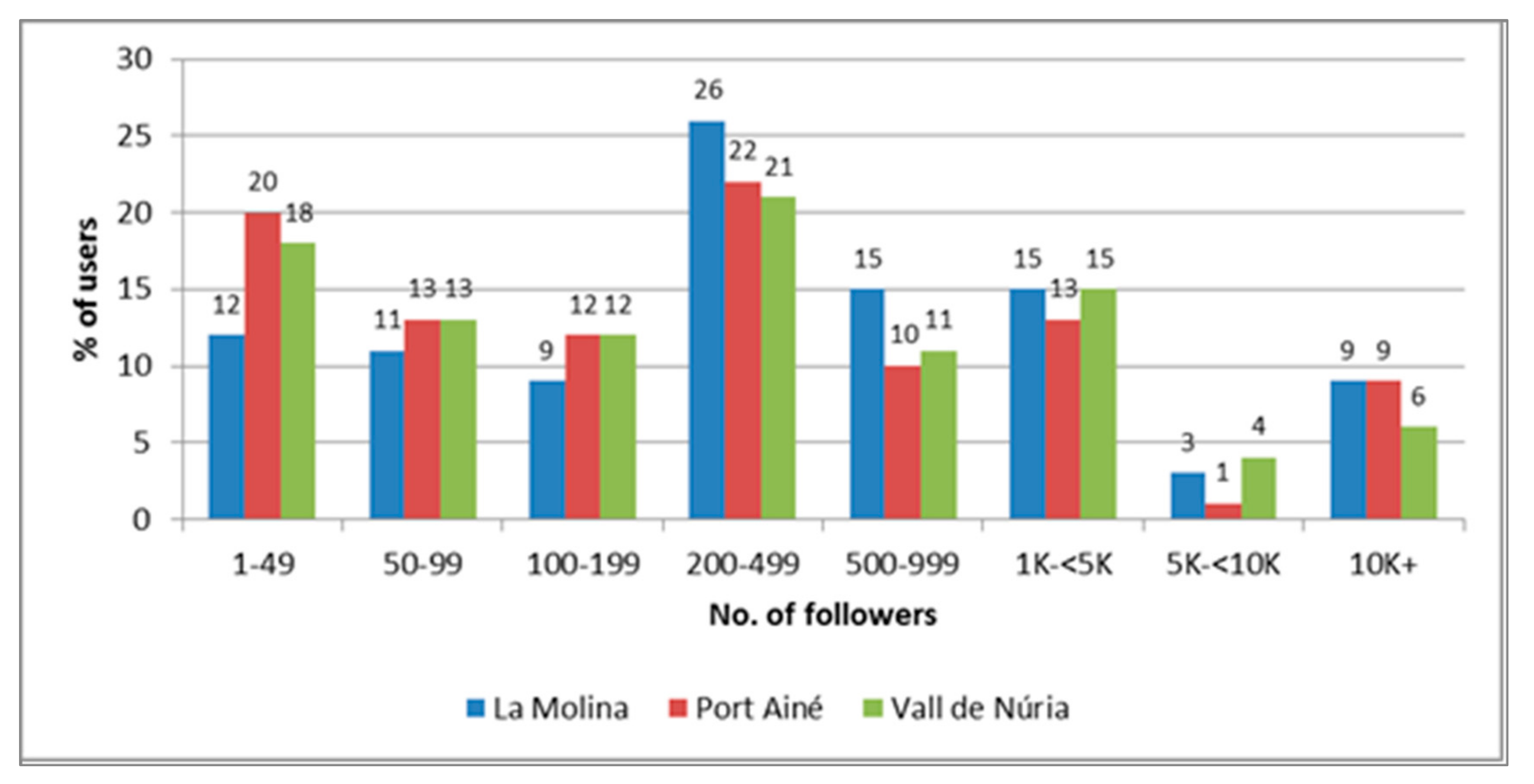

4.1. Participants (Users) Posting Pictures on Instagram and Dissemination

4.2. Posts and Interactivity through Instagram

4.3. Participant Observation

5. Discussion

- Online community (Figure 7a): UGEs are interesting from a sociological point of view in the sense that they represent the translation of an online community into a reality, with offline impacts. Parallel to UGC, UGEs have the characteristic that people attending may or may not know one another but they have the potential to reach thousands of anonymous people in seconds, and have the capacity to go viral. This idea is reinforced by the significant percentage of Instagrammer participants (about one third) who came to the event alone but nevertheless as a member of the community, participants’ strong interpersonal interactivity, and the crucial role of ‘influencers’ in brand dissemination. Moreover, both quantitative and qualitative results showed remarkable participant identification and faithfulness to these types of events in relation to the online community.

- UGC through social media (Figure 7b): The results showed that tourist UGEs are intrinsically related to the production of online UGC through social media and generate user engagement and interactivity through likes and comments. Social media are integrated within UGEs, to the extent that the event would not be possible, would lose all its significance or would not have happened without the specific social media, and would not have any significance either without people travelling physically to the site. The production of UGC in UGEs is a sine qua non condition, which indicates their high potential economic impact, as C2C communication through UGC in online communities encourages sales and those who communicate most are those who purchase the most [31].

- Engagement and faithfulness (attraction capacity) (Figure 7f): Participant observation, indicated the perception of intrinsic motives of altruism of the community and social identification [32] which encourage users to engage with the online brand communities. The engagement with the events through social media is very high. As shown by the quantitative results and in spite of the limited size of the events, for the three together, in a very short period of time, about 300 Instagram users posted 1290 pictures, creating high engagement and online ‘buzz’, receiving about 200,000 likes and 16,000 comments in total, and potentially reaching more than three-quarter of a million people (followers). All that at little or no cost to destinations or tourism businesses—both in terms of time or money. Moreover, as quantitative results demonstrate, UGEs have a great capacity to attract people, and specifically Instagram UGEs can have a great deal of influence on and attraction for destinations, reinforcing the idea of Baksi [44] of their emotional bonding capacity, their ability to generate favourable images of a destination, and loyalty. In this respect, both quantitative and qualitative results showed remarkable faithfulness to these events and high repeat rate, with more than 20% of participants attending more than one event, and most confirming they would like to participate in similar future events with like-minded people with whom they felt identified.

- Tourist brand/image dissemination (Figure 7g): The promotional capacity of UGEs though online image/brand dissemination is extremely important. Because they originated from an online community, tourism UGEs may entail greater dissemination than regular events which use social media as part of their promotion. At UGEs, and especially Instagram meetups, UGC production is part of what people ‘have’ to and ‘want’ to do to participate in the event. Participants partly engaged in the photography competition to win a prize, but even if the prize had not existed, they would have participated for community recognition to gain a reputation/prestige [17] as an Instagrammer, and for the hedonism of posting experiential pictures. The core idea that to be a tourist is almost by necessity to be a photographer [43] is maintained or even incremented in UGE contexts bound to social media, especially Instagram, where it is even more compulsory to take and post pictures. Therefore, in UGEs, the reproduction of tourist images [43] and the closing of the hermeneutic circle [68,69] through social media may be more intense, conscious, and purposeful, and contribute highly to promoting the destination or organization. Analysis shows that only a few selected photographs were posted on Instagram, probably the pictures users consider the ‘best’ or most ‘original’, offering an ideal picture of the place or the event. UGEs can also help to reinforce destination brand identity and image, as well as create and reinforce territorial links, related to tourism assets and offers.

- Influence and virality (Figure 7e): In relation to the latter, manifest content of online photographs has been found to influence the attitudes toward a destination and affect destination image formation [12]. If UGEs are successful and participants enjoy them and have fun, as the participant observation indicates, they will attach and transmit these sensations and feelings in relation to the destination, which will be reinforced by followers’ comments. The positive link between taking photographs and tourist satisfaction and happiness [45] is thus supported by participant observation. These positive sensations can then be a source of inspiration for other travellers, increasing their desire to travel to the destination and participate in future events. Besides, these events organized by peers of the tourist and the information they transmit through eWOM bound to online communities (organic sources) can have a greater impact and provide much more effective and trustworthy marketing for the destination or organization than official sources, which are seen as interested traditional forms of advertising (overt induced sources) according to Gartner’s [70] classification of tourist information sources. This idea of their high influence on users is reinforced by participant observation, which showed users’ attachment and identification. Users perceived the motives behind the events as altruistic and disinterested, related to pride in their own country and promoting tourism, as well as socializing and having fun, which makes them more “permeable” to influence. In essence, UGEs have what makes UGC so influential and trustworthy: no perceived underlying self-interest or economic interest. Remarkably, along the lines of Hartmann [33], a few highly influential users were detected, who accounted for the majority of online disseminations, showing the great potential influence of certain posts and their capacity to go viral, reaching thousands of people in seconds.

- Event convocation and management by users (Figure 7d): Tourism UGEs, especially in the case of Instagram meetups, and unlike other spontaneous events created through social media, show the organizational capacity and empowerment of users as they are fully structured or semi-structured, organized and managed by users, and may entail formal registrations, membership, etc. The paper results show that ski resorts and business brands participated and mixed with participants as just another participant, informally and not as ‘organizers’, thus becoming more ‘human’ in the eyes of tourists. The sponsor’s brand was clearly integrated in the event through the photography competition. The participant observation also showed in practice an event organization by peers and for peers, with meeting points, its publicity, participant identifications, group activities, etc.

- DMOs and tourism firms (Figure 7): Previous studies [2,33], although acknowledging people’s new empowered and central role in events through UGC, always assumed that the company or the destination is a co-organizer or has an important degree of control over the event, or that the organization initiates social media integration in the event as part of a marketing strategy. Evaluation models, too, have usually been proposed from a management perspective, from the point of view or interest of the organization, even if in some cases they acknowledge the role of different stakeholders, including users [21]. Nonetheless, the empowered role of users in events, enabled by social media, can be much deeper, to the point of a complete paradigm shift in which users are the main initiators, creators, organizers and realizers of the event. Methods must be sought which respond to this new context and can contribute to broader evaluation models. As pointed out above, social media are not only useful tools to promote an event but also to organize collective action [4]. However, in spite of not taking the event’s initiative, sponsors (firms or destinations) are convenient, and even necessary, for the creation of UGEs, as they make these events more attractive; provide logistical, economic, and/or promotional support and advantages for participants; and also result in promotional and economic benefits for organizations. Therefore, although the roles of companies and destinations in UGEs may change, they will likely continue to be very important for their development and collaboration in different ways.

- Paradigm shift: User initiative and empowerment (Figure 7c): The shift is that the event is at the initiative of the people, not the company or tourist destination, and it is taken in a user milieu. This reinforces the arguments which assess the empowerment of tourists and their increasing role as active agents [9,10,71] generating online content and events in a solely user milieu, for which tourism organizations have difficulty accessing, much less control. In this context, companies and destinations acquire a facilitating role, which may be more or less proactive and may entail promotion, sponsorships, etc., but the initiative is not theirs. Therefore, the sentence ‘We need to learn to let go’ (Lafley, as cited in Hartmann [33]) may even acquire a deeper meaning or be used to go further, as the control of the event may be mostly or even entirely out of the hands of the destination or organization. The sentence could be transformed into: Sometimes, organizations need to let go and let customers take the reins!

6. Concluding Remarks

6.1. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Dijck, J.; Poell, T. Understanding social media logic. Media Commun. 2013, 1, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, C. Ein überblick zu Events im Zeitalter von Social Media; An overview of events in the age of Social Media; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segerberg, A.; Bennett, W.L. Social Media and the organization of collective action: Using Twitter to explore the ecologies of two climate change protests. Commun. Rev. 2011, 14, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirky, C. The political power of social media. For. Aff. 2011, 90, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.; Tyrrell, T.J. Arizona meeting planners’ use of social networking media. In Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Sigala, M., Christou, E., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2012; pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, S.; Page, S.J.; Buhalis, D. Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.A.; Munar, A.M. The takeoff of social media in tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Christou, E.; Gretzel, U. Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Sigala, M., Christou, E., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marine-Roig, E. Measuring destination image through travel reviews in search engines. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Stepchenkova, S. Effect of tourist photographs on attitudes towards destination: Manifest and latent content. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Anton Clavé, S. Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of Barcelona. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-generated content as a research mode in tourism and hospitality applications: Topics, methods, and software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. New members’ integration: Key factor of success in online travel communities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Lee, H. Travelers’ social identification and membership behaviors in online travel community. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Seshadri, S. From virtual travelers to real friends: Relationship-building insights from an online travel community. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J.; Hudson, R. The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inversini, A.; Williams, N.L. Social media and events. In Events Management: An International Approach; Ferdinand, N., Kitchen, P.J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2016; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, F.; Scapolan, A.; Codeluppi, E. Identity and social media in an art festival. In Tourism Social Media: Transformations in Identity, Community and Culture; Munar, A.M., Gyimóthy, S., Cai, L., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Getz, D.; Pettersson, R.; Wallstam, M. Event evaluation: Definitions, concepts and a state of the art review. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2015, 6, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Whitford, M. An exploration of events research: Event topics, themes and emerging trends. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2013, 4, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Munday, R. A Dictionary of Social Media; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlaner, H.; Bò, G.D.; Pichler, S. Differences in perceived destination image and event satisfaction among cultural visitors: The case of the European Biennial of Contemporary Art “Manifesta 7”. Event Manag. 2013, 17, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, Y.-K. Impact of mega sport events on destination image and country image. Sport Mark. Q. 2014, 23, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.; Li, Y. Image impacts of planned special events: Literature review and research agenda. Event Manag. 2014, 18, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, P. A perspective on the near future: Mobilizing events and social media. In The Future of Events and Festivals; Yeoman, I., Robertson, R., McMahon-Beattie, U., Smith, K.A., Backer, E., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. A retrospective view of electronic word of mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 1–34, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, M.T.; Noble, S.M.; Noble, C.H. The influence of C2C communications in online brand communities on customer purchase behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 634–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.K. The impact of online brand community type on consumer’s community engagement behaviors: Consumer-created vs. marketer-created online brand community in online social-networking web sites. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, D. User generated events. In Erfolg mit Nachhaltigen Eventkonzepten; Zanger, C., Ed.; Gabler Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E. The Value of Connection: A Review of Social Media Trends; Meeting Professionals International (MPI): Dallas, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wittel, A. Toward a network sociality. Theory Cult. Soc. 2001, 18, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; van Dijck, J. Researching social media as if the social mattered. Soc. Media Soc. 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.D.; Zeng, W. Media on the Web. In Social Multimedia Signals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, I.S.; McKercher, B.; Lo, A.; Cheung, C.; Law, R. Tourism and online photography. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, K.; Erdem, M.; Okumus, F.; Bilgihan, A. Users’ attitudes toward online social networks in travel. In Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality; Sigala, M., Christou, E., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2012; pp. 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. Too many photographs? Photography as user generated content. AdComun. Rev. Cient. Estrateg. Tend. Innov. Comun. 2011, 2, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.; Donaghey, J.; Hare, J.; Hopkins, P.J. An Instagram is worth a thousand words: An industry panel and audience Q&A. Libr. Hi Tech News 2013, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwell, K.W. Dimensions of photography in a nature-based tour. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksi, A.K. Destination bonding: Hybrid cognition using Instagram. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2016, 6, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, S.; Schmitz, P.; Mitas, O. The snap-happy tourist: The effects of photographing behavior on tourists’ happiness. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum Boley, B.; Magnini, V.P.; Tuten, T.L. Social media picture posting and souvenir purchasing behavior: Some initial findings. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, A.H. Quantitative versus qualitative tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A. Best social media metrics: Conversation, amplification, applause, economic value. Digit. Mark. Anal. Blog 2011, 1–11. Available online: http://www.kaushik.net/avinash/best-social-media-metrics-conversation-amplification-applause-economic-value/ (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Zarrella, D. The Social Media Marketing Book; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; You, Y. Conceptualizing and measuring online behavior through social media metrics. In Analytics in Smart Tourism Design: Concepts and Methods; Xiang, Z., Fesenmaier, D.R., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Sidorova, Y. A performance measurement system to quantify the contribution of social media: New requirements for metrics and methods. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2016, 20, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, A.M.; Ognibeni, B.; Pauwels, K. Social media metrics—A framework and guidelines for managing social media. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Marine-Roig, E. Destination brand communication through the social media: What contents trigger most reactions of users? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A.; Marine-Roig, E. User reactions to destination brand contents in social media. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 15, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carah, N.; Shaul, M. Brands and Instagram: Point, tap, swipe, glance. Mob. Media Commun. 2016, 4, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Booch, G.; Rumbaugh, J.; Jacobson, I. Unified Modeling Language User Guide; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hopken, W. Reference model of an electronic tourism market. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Fesenmaier, D.R., Klein, S., Buhalis, D., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2000; pp. 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackellar, J. Participant observation at events: Theory, practice and potential. Int. J. Event Festiv. 2013, 4, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D. Research through participant observation in tourism: A creative solution to the measurement of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction (CS/D) among tourists. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijn, E.; Slumer, N.; Mitas, O. Click to share: Patterns in tourist photography and sharing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, D.L. Participant Observation: A Methodology for Human Studies; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt, K.M.; DeWalt, B.R. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers, 2nd ed.; AltaMira Press: Plymouth, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Special events: Defining the product. Tour. Manag. 1989, 10, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S. Instagram by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts. 2017. Available online: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/ (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Hu, Y.; Manikonda, L.; Kambhampati, S. What we Instagram: A first analysis of Instagram photo content and user types. In Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM 2014), Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; pp. 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, E.; Interdonato, R.; Tagarelli, A. Online popularity and topical interests through the lens of Instagram. In ACM Hypertext and Social Media; ACM Digital Library: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instagram. Instagram Community. 2017. Available online: https://community.instagram.com/ (accessed on 4 April 2017).

- Caton, K.; Almeida Santos, C. Closing the hermeneutic circle? Photographic encounters with the other. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E. Identity and authenticity in destination image construction. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 26, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M. Tourist-created content: Rethinking destination branding. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 5, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Tosun, C. Arguments for community participation in the tourism development process. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the economic impacts of a small-scale sport tourism event: The case of the Italo-Swiss mountain trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| La Molina (LM) | Port Ainé (PA) | Vall de Núria (VN) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ski area/slopes | 61 km/53 | 30 km/25 | 7 km/11 |

| Winter season (14/15) Visitors | 265,798 | 105,296 | 45,944 |

| Influx (avg. daily visitors) | 2950 | 1170 | 510 |

| Day of the event | 18/01/2015 | 22/02/2015 | 08/03/2015 |

| Participant places | 200 places | 450 places | 500 places |

| Specific event hashtags | #descobreixlamolina #clicalamolina | #descobreixportaine #clicaportaine | #descobreixvalldenuria #clicavalldenuria |

| Instagram account | @lamolinaski | @port_aine | @valldenuria |

| Different Users Posting Photos | Total Followers of Users | Avg. Followers Per User | Max. Followers | Average Posts Per User | Max. Number of Posts | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM | 104 | 291,434 | 2802.25 | 40,200 | 4.67 | 23 |

| PA | 91 | 236,811 | 2602.32 | 38,900 | 4.05 | 34 |

| VN | 110 | 256,562 | 2332.38 | 39,780 | 4.00 | 20 |

| LM | PA | VN | LM + PA | PA + VN | LM + VN | All 3 | SUM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of users | 65 | 53 | 68 | 11 | 12 | 18 | 11 | 238 |

| Percent | 27.3 | 22.3 | 28.6 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 4.6 | 100 |

| Total Photos | Total Likes | Avg. Likes Per Photo | Max. Likes | Total Comments | Avg. Comments Per Photo | Max. Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM | 486 | 85,707 | 176.35 | 1453 | 7763 | 15.97 | 136 |

| PA | 360 | 47,989 | 133.30 | 1565 | 3694 | 10.23 | 130 |

| VN | 444 | 60,558 | 136.39 | 1835 | 4572 | 10.30 | 97 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marine-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Daries-Ramon, N. User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122250

Marine-Roig E, Martin-Fuentes E, Daries-Ramon N. User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122250

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarine-Roig, Estela, Eva Martin-Fuentes, and Natalia Daries-Ramon. 2017. "User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122250