The Determinants of Tourist Use of Public Transport at the Destination

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data

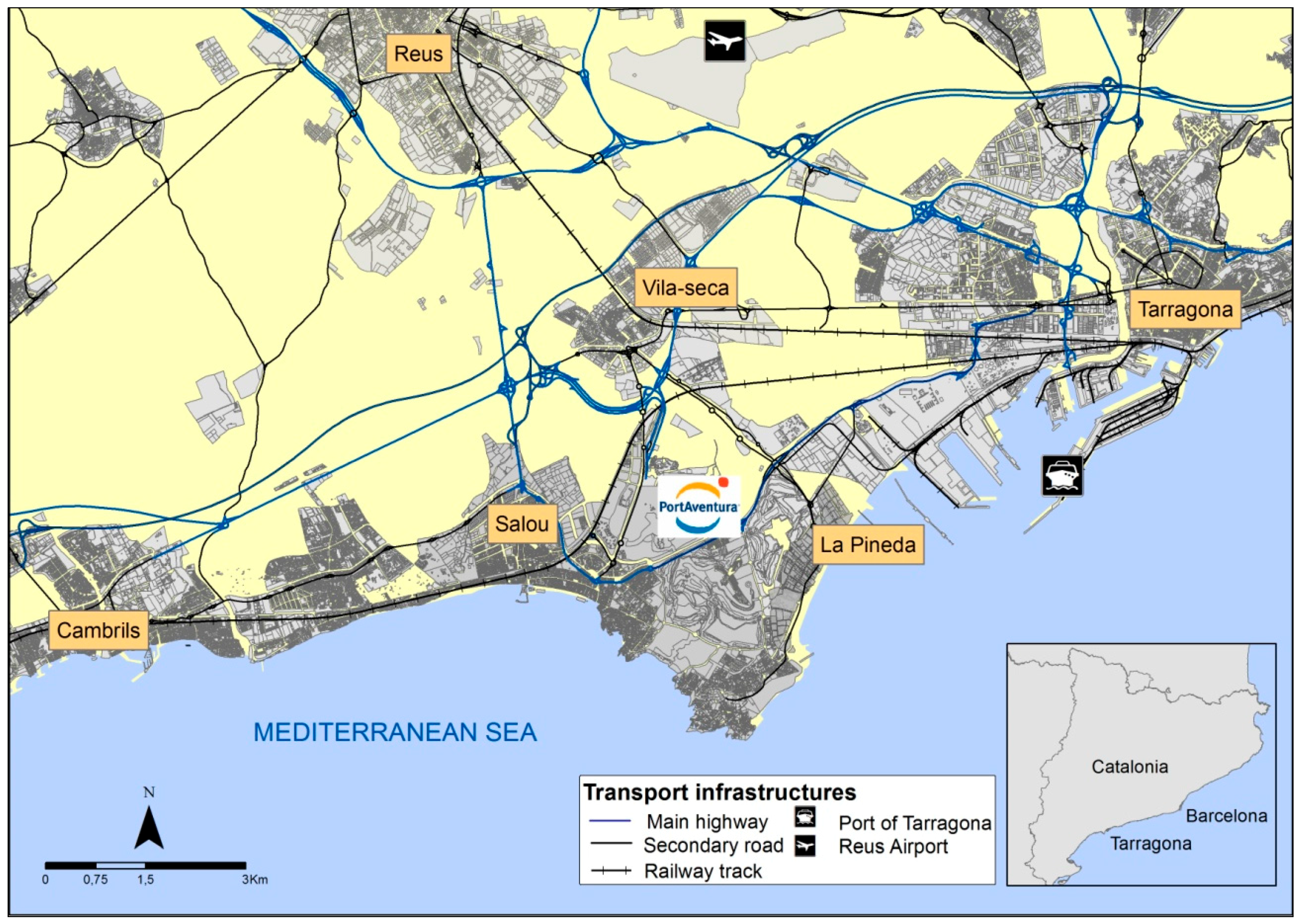

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Questionaire and Data Collection

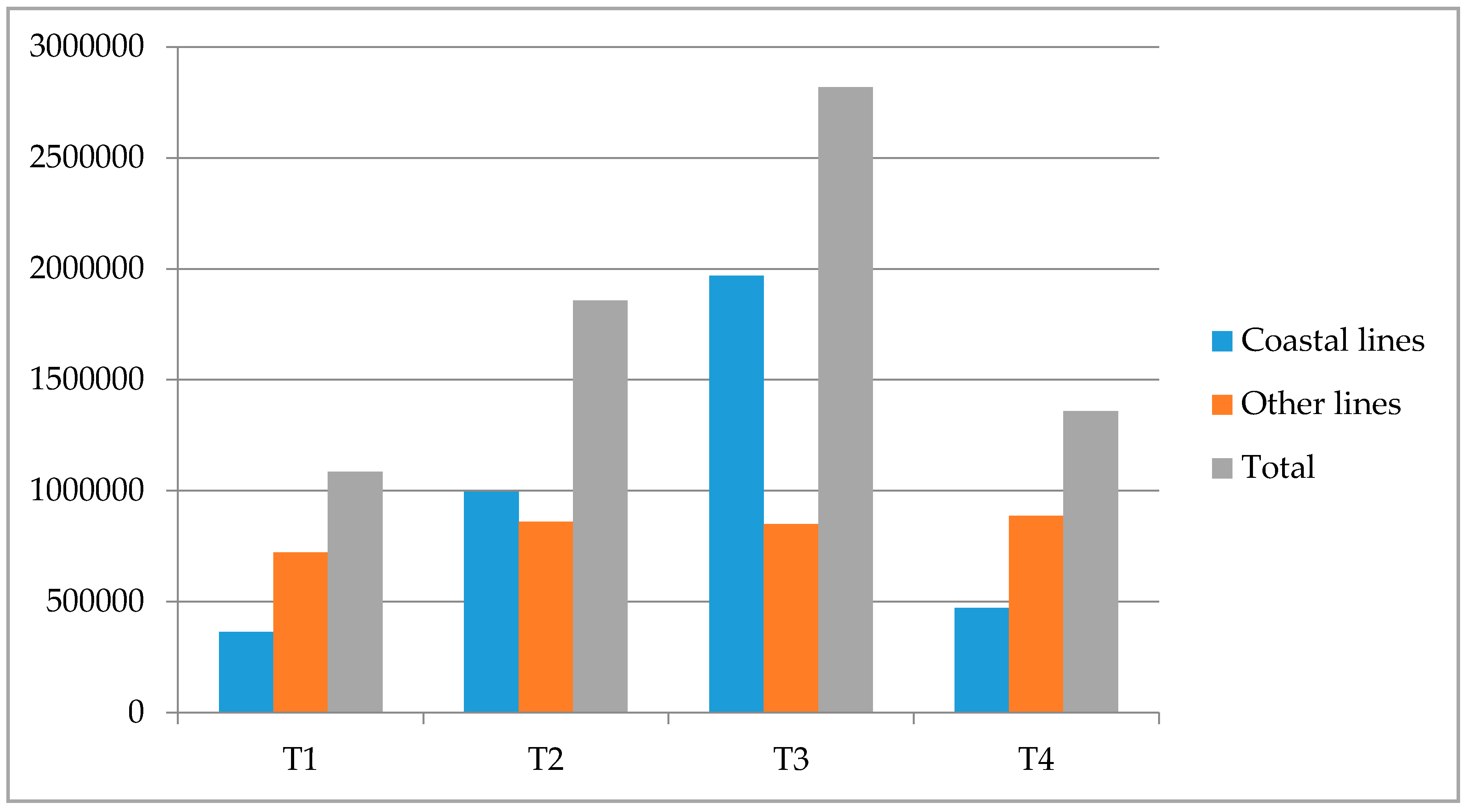

3. Descriptive Statistics

4. Methodology: Model Specification

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The Probability of Using Different Transport Modes to Reach the Destination

5.2. The Probability of Using Public Transport at the Destination

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lumsdon, L.; Page, S.J. Tourism and Transport: Issues and Agenda for the New Millennium; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. Transport and Tourism: Global Perspectives; Harlow: Pearson, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, D.T. Tourism and Transport: Modes, Networks and Flows; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. Tourism and Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prideaux, B. The role of the transport system in destination development. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronau, W.; Kagermeier, A. Key factors for successful leisure and tourism public transport provision. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; Schofield, P. An investigation of the relationship between public transport performance and destination satisfaction. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.T.; Gerike, R.; Hall, C.M. Visitor users vs. non-users of public transport: The case of Munich, Germany. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Jia, L.; Jiang, L. Forest recreation opportunity spectrum in the suburban mountainous region of Beijing. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2012, 138, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeno, T.G. Is Tourism a Driver for Public Transport Investment? Master’s Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G. Tourism and urban public transport: Holding demand pressure under supply constraints. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, G.; Peeters, P.; Ceron, J.P.; Gössling, S. The future tourism mobility of the world population: Emission growth versus climate policy. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2011, 45, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Urban transport transitions: Copenhagen, City of Cyclists. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Szimba, E.; Duijnisveld, M. Major environmental impacts of European tourist transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Carbon management in Tourism: Mitigating the Impacts on Climate Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. The primacy of climate change for sustainable international tourism. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Le-Klähn, D.T.; Ram, Y. Tourism, Public Transport and Sustainable Mobility; Channel View Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Peeters, P. Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy? The costs and risks of carbon reduction pathways. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. A report on the Paris Climate Change Agreement and its implications for tourism: Why we will always have Paris. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiver, J.; Lumsdon, L.; Weston, R. Traffic reduction at visitor attractions: The case of Hadrian’s Wall. J. Transp. Geogr. 2008, 16, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Robbins, D.; Fletcher, J. Representation of transport: A rural destination analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Dubois, G. Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, E.W.; Dougherty, T.D. Planning Sustainable Tourism Destinations. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2000, 25, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schianetz, K.; Kavanagh, L.; Lockington, D. Concepts and tools for comprehensive sustainability assessments for tourism destinations: A comparative review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasekara, G.N.; Fukahori, K. Environmental correlates that provide walkability cues for tourists: An analysis based on walking decision narrations. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2013, 4, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, J.; Caulfield, B. An examination of the quality and ease of use of public transport in Dublin from a newcomer’s perspective. J. Public Transp. 2011, 14, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.T.; Hall, C.M. Tourist use of public transport at destinations—A review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Lai, T.Y. The Taipei MRT (Mass Rapid Transit) tourism attraction analysis from the inbound tourists’ perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G. Entre marche et métro, les mouvements intra-urbains des touristes sous le prisme de l’«adhérence» à Paris et en Île-de-France. Rech. Transp. Sécur. 2012, 28, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Clavé, S. Leisure parks and destination redevelopment: The role of Port Aventura, Catalonia. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 2, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J. (Ed.) TEA/AECOM 2014. In Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report; Themed Entertainment Association (TEA): Burbank, CA, USA, 2015.

- Wooldridge, J.M. Quasi-maximum likelihood estimation and testing for nonlinear models with endogenous explanatory variables. J. Econom. 2014, 182, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Trivedi, P.K. Maximum simulated likelihood estimation of a negative binomial regression model with multinomial endogenous treatment. Stata J. 2006, 6, 246–255. Available online: http://www.stata-journal.com/article.html?article=st0105 (accessed on 14 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Deb, P.; Trivedi, P.K. Specification and simulated likelihood estimation of a non-normal treatment-outcome model with selection: Application to health care utilization. Econom. J. 2006, 9, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, D.; Trivedi, P.K. What Drives Differences in Health Care Demand? The Role of Health Insurance and Selection Bias. Health, Econometrics and Data Group (HEDG) Working Papers 2012, 12/09. Available online: http://www.york.ac.uk/media/economics/documents/herc/wp/12_09.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Leoni, T.; Eppel, R. Women’s Work and Family Profiles over the Lifecourse and Their Subsequent Health Outcomes. Evidence for Europe. WWWforEurope Working Paper 28, 2013. Available online: http://www.foreurope.eu/fileadmin/documents/pdf/Workingpapers/WWWforEurope_WPS_no028_MS7.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Deb, P.; Seck, P. Internal Migration, Selection Bias and Human Development: Evidence from Indonesia and Mexico. Human Development Research Paper 31, 2009. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2009/papers/HDRP_2009_31.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Frech, A.; Damaske, S. The relationships between mothers’ work pathways and physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2012, 53, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz-Costa, C.; Besen, E.; James, J.B.; Pitt-Catsouphes, M. Differential impact of multiple levels of productive activity engagement on psychological well-being in middle and later life. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Chan, C.W.; Olivares, M.; Escobar, G. ICU Admission Control: An empirical study of capacity allocation and its implication on patient outcomes. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefond, C.; Clément, M. Social class and body weight among Chinese urban adults: The role of the middle classes in the nutrition transition. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 112, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triventi, M. Does working during Higher Education affect students' academic progression? Econ. Edu. Rev. 2014, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, A. (Endogenous) occupational choices and job satisfaction among recent Spanish PhD recipients. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J. Choosing Schools, Building Communities? The Effect of Schools of Choice on Parental Involvement. Institute of Education Sciences, Education Working Paper Archive, 2007. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED508943.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Deb, P. “MTREATREG: Stata Module to Fits Models with Multinomial Treatments and Continuous, Count and Binary Outcomes Using Maximum Simulated Likelihood”, Statistical Software Components S457064, Boston College Department of Economics, Revised 14 July 2009. Available online: http://fmwww.bc.edu/repec/bocode/m/mtreatreg.ado (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Koo, T.T.R.; Wu, C.L.; Dwyer, L. Dispersal of visitors within destinations: Descriptive measures and underlying drivers. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.T.; Hall, C.M.; Gerike, R. Analysis of visitor satisfaction with public transport in Munich, Germany. J. Public Transp. 2014, 17, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Klähn, D.T.; Roosen, J.; Gerike, R.; Hall, C.M. Factors affecting tourists’ public transport use and areas visited at destinations. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Haider, W.; Williams, P.W. A behavioral assessment of tourism transportation options for reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gases. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Smallman, C.; Wilson, J.; Simmons, D. Dynamic in-destination decision-making: An adjustment model. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L.; Zoltan, J. Tourists intra-destination visits and transport mode: A bivariate model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 43, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanfo, S.; Dissanayake, D. Modelling surface access mode choice of air passengers. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Transp. 2009, 162, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, S.; Lyons, G. To use or not to use? An empirical study of pre-trip public transport information for business and leisure trips and comparison with car travel. Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Santos, G.E.; Ramos, V.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Determinants of multi-destination tourism trips in Brazil. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1331–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | (1) Mean N = 4336 | (2) Mean N = 1997 | (3) Mean N = 1919 | (4) Mean N = 420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | Use of public transport during holidays | 0.57 | 0.40 | 0.73 | 0.66 |

| Transport-own | Transport mode to arrive: own vehicle | 0.46 | - | - | - |

| Transport-plane | Transport mode to arrive: plane | 0.44 | - | - | - |

| Transport-pt | Transport mode to arrive: public transport | 0.10 | - | - | - |

| Origin-Spain | Origin: mainland Spain (excluding Balearic Islands, Canary Islands and Ceuta) | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.68 |

| Origin-France | Origin: France, Andorra and Monaco (excluding Corsica) | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Origin-2000 km | Origin: countries located less than 2000 km from the destination (excluding France and Spain) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Origin-further | Origin: countries over 2000 km from the destination and overseas territories | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.11 |

| Class-high | Upper class | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.18 |

| Class-mid | Middle class | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Class-low | Low class | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.46 |

| Class-unknown | Unknown social class | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Accom-2home | Accommodation in second residence | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Accom-other | Unknown accommodation | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Accom-apart | Accommodation in rented apartment | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Accom-camp | Accommodation at a camp site | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Accom-family | Accommodation in residence of friends or relatives | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Accom-hotel1 | Accommodation in a 1, 2 or 3 star hotel | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.36 |

| Accom-hotel2 | Accommodation in a 4 or 5 star hotel | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| Age-24 | Up to 24 years old | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Age-44 | From 25 to 44 years old | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.18 |

| Age-64 | From 45 to 64 years old | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.30 |

| Age-older | 65 years old and older | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

| Expenses-low | Spending at the destination: low | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.33 |

| Expenses-mid | Spending at the destination: medium | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.22 |

| Expenses-high | Spending at the destination: high | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.17 |

| Expenses-unknown | Spending at the destination: unknown | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.28 |

| Place-Cambrils | Municipality of destination: Cambrils | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Place-Pineda | Municipality of destination: La Pineda | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.22 |

| Place-Salou | Municipality of destination: Salou | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.62 |

| Duration-1week | Duration of stay, 1 week or less | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| Duration-2weeks | Duration of stay between 8 and 14 days | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.58 | 0.40 |

| Duration-longer | Duration of stay of longer than 14 days | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Who-friends | Accompanied by: friends | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| Who-firm | Accompanied by: business trip | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Who-school | Accompanied by: study trip | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Who-family | Accompanied by: family trip | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Who-children | Accompanied by: family trip with children | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.13 |

| Who-partner | Accompanied by: trip with partner | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| Who-senior | Accompanied by: IMSERSO trip | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| Who-alone | Accompanied by: travelling alone | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Repeat | Not the first visit to the Costa Daurada | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.39 | 0.67 |

| Sex-man | Male | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.44 |

| No visiting | Not making any tourist trips during the stay | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

| Org-other | Organisation of the trip: organised by others | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.76 | 0.63 |

| Org-own | Organisation of the trip: organised by self | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.33 |

| Org-unknown | Organisation of the trip: organised by unknown person/entity | 0.27 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Plane vs. Own Car | Public Transport vs. Own Car | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | St. Error | Coefficient | St. Error | |

| Intercept | −1.3797 | (0.2984) *** | −0.8812 | (0.2993) *** |

| Origin-Spain | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Origin-France | 0.0112 | (0.2125) | −1.6446 | (0.228) *** |

| Origin-2000 km | 3.4979 | (0.2241) *** | 0.4288 | (0.2614) |

| Origin-further | 6.6010 | (0.2666) *** | 1.4150 | (0.2988) *** |

| Class-mid | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Class-high | 0.0765 | (0.1928) | 0.0388 | (0.2027) |

| Class-low | −0.0361 | (0.1998) | 0.1790 | (0.1945) |

| Class-unknown | −0.0595 | (0.4552) | 0.0705 | (0.3933) |

| Accom-hotel1 | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Accom-2home | 0.8245 | (0.3661) ** | 1.1214 | (0.3759) *** |

| Accom_other | −0.3175 | (1.0515) | 0.4761 | (1.2082) |

| Accom-apart | −0.2888 | (0.2559) | −0.6208 | (0.2796) ** |

| Accom-camp | −3.6304 | (0.549) *** | −2.2502 | (0.5839) *** |

| Accom-family | 2.2367 | (0.3929) *** | 2.6558 | (0.4231) *** |

| Accom-hotel2 | −0.8299 | (0.2035) *** | −0.4375 | (0.1972) ** |

| Age-44 | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Age-24 | 0.5973 | (0.3355) * | 1.6863 | (0.3173) *** |

| Age-64 | 0.5102 | (0.1958) *** | 0.6108 | (0.2104) *** |

| Age-older | 1.6950 | (0.2632) *** | 1.7540 | (0.2689) *** |

| Expenses-mid | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Expenses-low | −0.1180 | (0.2014) | −0.0167 | (0.2039) |

| Expenses-high | 0.2133 | (0.215) | −0.0090 | (0.2355) |

| Expenses-unknown | −0.1403 | (0.244) | 0.1352 | (0.2291) |

| Place-Salou | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Place-Cambrils | −0.9157 | (0.2064) *** | −0.8112 | (0.2112) *** |

| Place-Pineda | −0.3930 | (0.199) ** | −0.4523 | (0.1918) ** |

| Duration-1week | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Duration-2weeks | 1.1038 | (0.1694) *** | 0.6254 | (0.1824) *** |

| Duration-longer | 0.1891 | (0.31) | 0.3534 | (0.2905) |

| Repeat | −1.1093 | (0.1683) *** | −0.4795 | (0.1731) *** |

| Sex-man | −0.3114 | (0.1502)** | −0.3487 | (0.1507) ** |

| No visiting | −0.6039 | (0.1772) *** | 0.0683 | (0.1667) |

| Org-other | Reference category | Reference category | ||

| Org-own | −0.1350 | (0.1832) | −0.3811 | (0.1828) ** |

| Org-unknown | −4.6563 | (0.3523) *** | −5.5251 | (0.4779) *** |

| Coefficient | St. Error | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −1.5097 | (0.3234) *** |

| Transport-own | Reference category | |

| Transport-plane | 2.4575 | (0.4378) *** |

| Transport-pt | 1.2113 | (0.5313) ** |

| Class-mid | Reference category | |

| Class-high | 0.2771 | (0.1273) ** |

| Class-low | 0.1604 | (0.137) |

| Class-unknown | 0.5089 | (0.2777) * |

| Accom-hotel1 | Reference category | |

| Accom-2home | 0.7999 | (0.2829) *** |

| Accom_other | −0.4722 | (0.4653) |

| Accom-apart | 0.0272 | (0.1776) |

| Accom-camp | 0.0192 | (0.2912) |

| Accom-family | −0.0985 | (0.264) |

| Accom-hotel2 | −0.1731 | (0.1351) |

| Age-44 | Reference category | |

| Age-24 | −0.0759 | (0.2236) |

| Age-64 | −0.0325 | (0.1171) |

| Age-older | −0.2537 | (0.1758) |

| Expenses-mid | Reference category | |

| Expenses-low | −0.4723 | (0.1465) *** |

| Expenses-high | 0.2729 | (0.1393) * |

| Expenses-unknown | −0.6883 | (0.1813) *** |

| Place-Salou | Reference category | |

| Place-Cambrils | −0.3273 | (0.1452) ** |

| Place-Pineda | 0.1441 | (0.1198) |

| Who-children | Reference category | |

| Who-friends | 0.0572 | (0.1874) |

| Who-firm | −0.4853 | (0.6181) |

| Who-school | −0.3568 | (0.8384) |

| Who-family | 0.1141 | (0.1595) |

| Who-partner | −0.0001 | (0.1215) |

| Who-senior | 0.1140 | (0.2912) |

| Who-alone | 0.1575 | (0.2373) |

| Duration-1week | Reference category | |

| Duration-2weeks | 0.5984 | (0.1549) *** |

| Duration-longer | 1.0765 | (0.2506) *** |

| Repeat | 0.8010 | (0.1875) *** |

| Sex-man | 0.0296 | (0.092) |

| No visiting | −0.6598 | (0.1545) *** |

| Org-other | Reference category | |

| Org-own | 0.0327 | (0.1336) |

| Org-unknown | 0.1854 | (0.291) |

| Lambda plane | −1.1709 | (0.4107) *** |

| Lambda PT | 0.8250 | (0.9521) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez, A.; Miravet, D. The Determinants of Tourist Use of Public Transport at the Destination. Sustainability 2016, 8, 908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090908

Gutiérrez A, Miravet D. The Determinants of Tourist Use of Public Transport at the Destination. Sustainability. 2016; 8(9):908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090908

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez, Aaron, and Daniel Miravet. 2016. "The Determinants of Tourist Use of Public Transport at the Destination" Sustainability 8, no. 9: 908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090908