1. Introduction

Throughout the years, several frameworks for sustainability have set themselves up as milestones of both conceptual and empirical studies despite the proliferation of various standpoints. In this respect, the Triple-Bottom-Line (TBL) coined by Elkington [

1] succeeded in explaining the main components of sustainability assessment, that is, people, planet and profit. Considering these three elements in an integrative model, TBL has advanced a new perspective on the correlations between economic prosperity, social justice and environmental protection and posited the importance of long-term objectives [

2,

3,

4,

5].

Progressively, the need for an overall approach considering social, ecological and economic settings has catalyzed a paradigm shift in the business world. In search of viable solutions to develop their organizations, entrepreneurs have become more open to societal and environmental issues. They started paying more attention to community growth, to human rights in general and to workforce conditions in particular. They acknowledged that it is imperative to ensure a suitable working climate for all human resources and a responsible attitude towards health care policies, organizational learning and social understanding [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Furthermore, entrepreneurs began to attach greater importance to ecological issues, ranging from environmental protection, sustainable technology and clean product development to the application of strong ethical principles in entrepreneurial decisions. This led to the emergence of a new perspective on business profitability, now referred to as firm performance in a sustainability-driven context, where social and environmental values are of the essence [

8,

10].

Assuming the rationale of market disequilibria and the need to embrace responsible and balanced behaviors, the present research aims at testing the approach of Romanian SME entrepreneurs regarding the Triple-Bottom-Line. The subjects’ perceptions and attitudes (henceforth referred to as “approaches”) towards implementing the TBL imperatives within their organizations are discussed in relation to achieving business performance. The main reason for designing the current study lies in the fact that the extant literature on developing countries has scarcely approached the relationship between the aforementioned variables. Achieving holistic business performance is linked to considering all the factors of sustainable development, especially in the context of developed countries [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,], and, consequently, investigating a complementary perspective would fill a research gap.

From this perspective, the main research question is whether there is a positive relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship and business performance in the case of Romanian SMEs. Sustainable entrepreneurship is addressed, taking into account social aspects (attention is given to stakeholders, such as community, partners, workers,

etc.), environmental aspects (referring to long-term protection and negative effect reduction), and economic aspects (focus on economic growth while keeping in mind the previous two dimensions) [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

11,

15,

16,

17].

The study is organized as follows. The research hypotheses and the conceptual model are inferred. The method is thoroughly discussed, paying heed to the measurement and structural model evaluations. The results of the research are described, underscoring the theoretical and practical implications of the findings, the research limitations and the future research directions.

2. Research Hypotheses Development

Stressing the primacy of people, Bell and Stellingwerf [

8] noticed that sustainable business ventures involve highly motivated entrepreneurs who seek to solve social problems, paying attention to human resource management in terms of hiring, continuous development (by building a learning environment and culture) and training of the right people within the business. The authors underscore the importance of maintaining both a trust-based and reciprocal relationship with those involved in the business—sustainable entrepreneurs need to provide a sense of responsibility and accountability and make sure that exploitation (involving any stakeholders, like workers, partners, community) does not occur.

According to past studies, a growing interest has been shown in socially responsible endeavors, insisting on their potential to determine operational efficiency, organizational profitability or maximum safety at each level (

i.e., working conditions), product quality and innovation, an efficient dialogue with stakeholders, and development of responsible citizenship [

15]. Here, Pearce and Doh [

18] (p. 32) support the approach of successful collaborative social initiatives described as “joint projects that generate value to both private and nonprofit participants”. In this vein, focusing on the first pillar of the TBL, we infer that:

H1: Sustainable entrepreneurship approaches towards people generate a significant positive influence on business performance.

Within the TBL framework, profit refers both to general and specific benefits (

i.e., local community, society, respectively organizational benefits) that the involved entities obtain from sustainable business practices. Drawing from Venkataraman’s [

19] view on entrepreneurship, Cohen and Winn [

20] define sustainable entrepreneurship through the lens of generic benefits and bring forward the importance of how “future” goods and services are discovered, created, and exploited, by whom, and with what economic, psychological, social, and environmental consequences. They emphasize the need for a multi-faceted analysis of how sustainable new businesses perform financially, by following a general benefit-driven perspective. This view is indicative of Cohen and Winn’s standpoint [

20]; they posit that sustainable systems can be characterized as “complex, dispersed, global, uncertain, interdependent and having long-term horizons”.

The orientation of companies towards sustainability is hereby assessed by analysing the economic welfare goal [

9] (p. 3), the pursuance of “business opportunities to bring into existence future products, processes and services, while contributing to sustain the development of society, the economy and the environment and consequently to enhance the well-being of future generations”. In this point, Margolis, Elfenbein and Walsh [

21] determined that companies performing well from a financial standpoint are also more involved in engaging in social performance, referring to possible causes such as risk mitigation (considering reputation can suffer damages and may impact the financial performance), external expectations, reciprocity and guilt. Schaltegger and Wagner [

6] stress the key role of stakeholders who have expectations and demands, providing relevant input for business opportunities and performance. For the purposes of this research, the profit goal is linked to the generic benefits for stakeholders as people, groups, organizations, communities and essentially any entity “who may or may not have legitimate claims, but who may be able to affect or are affected by the firm” [

22] (p. 857).

Shepherd and Patzelt [

23] imply that sustainable entrepreneurship can be linked to pro-social behaviour, considering the orientation of entrepreneurial actions to provide benefits to other people. Work towards achieving collective benefits, preserving communities and contributing to network development is driven by the entrepreneurs’ perceptions of desirability and feasibility (influenced by personal, situational and cultural factors) and by acknowledging them as business performance inputs [

24,

25,

26]. Building on this logic, we infer that:

H2: Sustainable entrepreneurship approaches towards long-term collective benefits generate a significant positive influence on business performance.

While considering the third pillar of TBL, the environment, sustainable businesses need to address biodiversity and the protection of the environment when conducting business operations [

8]. For instance, Schaltegger and Wagner [

6] (p. 223) suggest that entrepreneurs can achieve environmental goals through innovative means like market innovations, defining “actors and companies making environmental progress to their core business” as sustainable entrepreneurs. Thus the authors relate a new way of doing things (products, services,

etc.) to increasing social and environmental health), connecting environmental progress to market success. This perspective has been supported by Rajasekaran [

27] and Fink

et al. [

28] as well. Other authors [

27,

29,

30,

31] state that entrepreneurs become co-creators of the environments in which they operate, working towards building their own networks, trying to create changes in the system context (institutions) by using these networks formed of actors who seek to challenge the status quo and to increase their business performance [

29] (p. 521). Starting from these standpoints, we infer that:

H3: Sustainable entrepreneurship approaches on environment protection generate a significant positive influence on business performance.

According to the depicted theoretical developments and advanced hypotheses, the current paper will address—in the context of Romanian SMEs—the following research model (

Figure 1):

4. Results

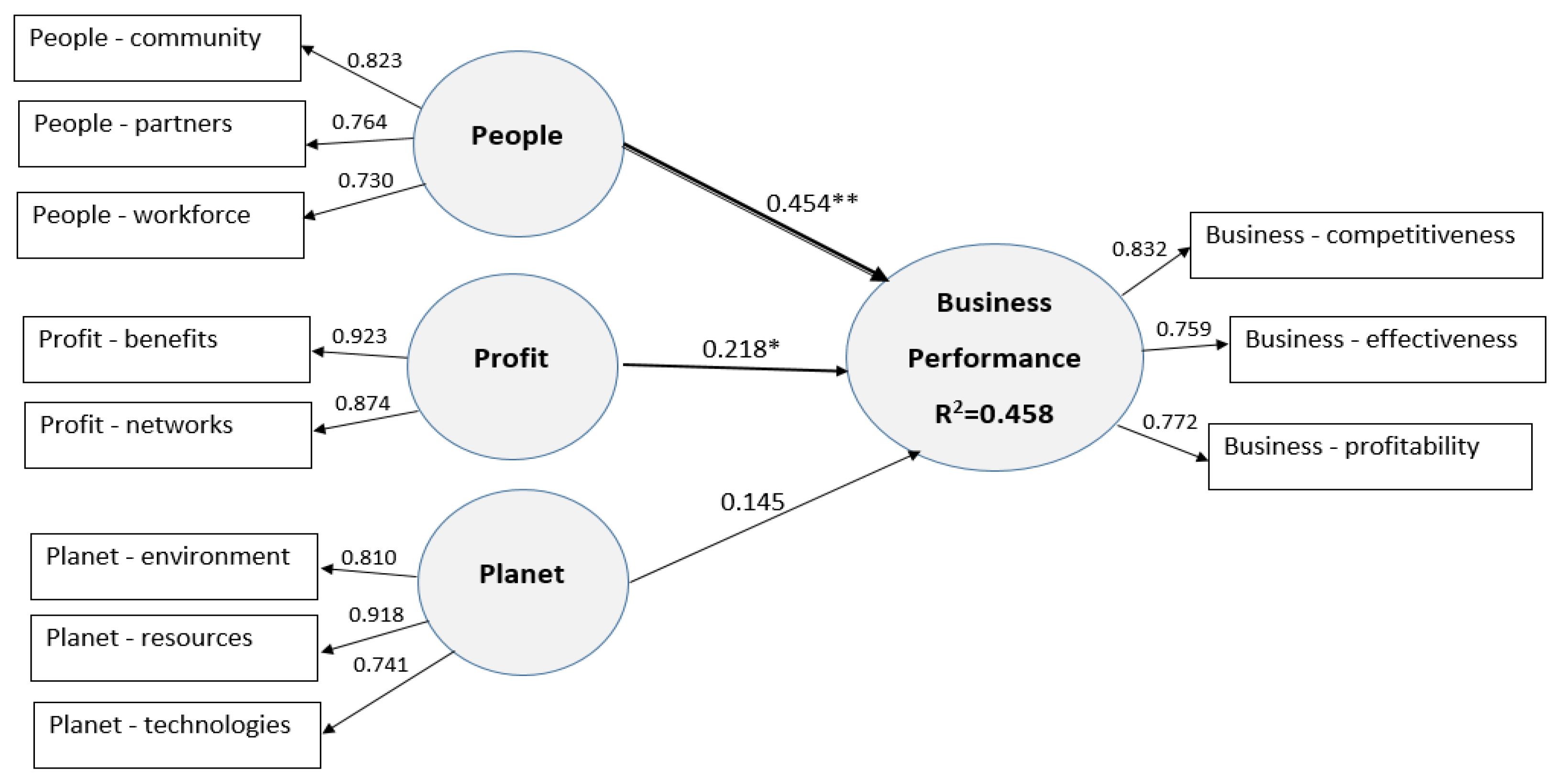

PLS structural model results are shown in

Figure 2. Applied to the context of Romanian SMEs, the model accounts for 45.8 percent of variance in business performance understood in terms of profitability, effectiveness and competitiveness.

As shown in

Figure 2, sustainable entrepreneurship

approaches towards people generate a significant positive influence on business performance (

β = 0.45,

p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. This situation is consistent with the findings of other similar studies which addressed the positive outcomes and impact of sustainable entrepreneurship endeavors regarding people (workforce, partners, stakeholders, generally speaking) [

5,

6,

10,

15,

24,

28]. Nevertheless, in this perspective, the value added by the current paper is the advancement

of a SME

framework of research.

Moving forward, the investigation of the second hypothesis supported the relationship between the sustainable entrepreneurship approaches towards long-term collective benefits and business performance. In other words, the entrepreneurs’ openness and propensity towards yielding long-term benefits to the larger community and operating within business networks for achieving tenable economic goals have a significant positive influence on business performance as suggested by the results (

β = 0.21,

p < 0.05). The findings confirm the theoretical standpoints depicted by the literature review [

9,

20,

24,

25,

29].

Although the planet issues play a very important role in the equation of sustainable entrepreneurship, the present research has not brought to the fore a significant relationship between the assumption of environment protection and business performance (

β = 0.14,

p > 0.05). Consequently, the third hypothesis of the study is not supported in the context of the investigated SMEs. Here, the results are not consistent with the works of Crowther and Aras [

16], Kirkwood and Walton [

26], Bell and Stellingwerf [

8],

etc., which assumed the existence of a significant positive relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship—in terms of harmless products and services, responsible policies regarding material and energy resources usage and the exploitation of green technologies—and business performance. One pertinent explanation may reside in the fact that the imperative for environment-responsible attitudes in developing countries is yet to be assumed among entrepreneurs. Nowadays, in Romania, there are many legislation voids regarding environment protection and the organizational culture of SMEs is unconditionally afflicted, unlike the profit and people policies, which are more thoroughly supported by legislation and culture.

To conclude, two out of the three proposed hypotheses were supported, confirming that sustainable entrepreneurship approaches towards people and profit dimensions result in a better business performance in the case of the Romanian SMEs which were included in the study.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Research Originality: Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current research adds to the existent literature in two different ways.

On the one hand, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between sustainable entrepreneurship and business performance has been scarcely addressed in the context of SMEs. Researchers have been mainly interested in scrutinizing the case of larger organizational actors, namely corporations, underscoring the implications and importance of CSR policies and best practices. Moreover, a detailed study on SMEs entrepreneurs in European developing countries (as Romania) had yet to be conducted.

On the other hand, the study brings forward the exploration of sustainable entrepreneurship using an important statistical tool which is still less known and valued by researchers in developing countries. At this level, by using PLS-SEM in the analysis of sustainability-related hypotheses, a methodological precedent may be created, with researchers admitting its pertinence and utility in similar research endeavours. Following the principle that precedents can be created, not just followed, the current paper stresses the advantages of using PLS-SEM in testing, measuring and evaluating research models in various organizational frameworks.

Focusing on the theoretical and practical implications of the research, several aspects may be considered significant. Firstly, the study shows a positive entrepreneurial attitude towards people and profit (within the logic of TBL) which might be seen as a prerequisite of future business conduct, described here as sustainable entrepreneurship. The survey conducted with 109 SMEs in Romania reveals that sustainable entrepreneurship (even in developing countries) has come to inherently encapsulate social and economic issues in an interconnected dyad of elements which accounts for long-term firm performance. In this view, economic and non-economic objectives are simultaneously considered among business priorities and impose themselves as a counterforce to sheer profit-driven actions.

Secondly, from a more practical perspective, the findings set themselves up as a frame of reference for new entrepreneurs interested in exploiting the market dynamics, in seizing opportunities and advancing proper solutions. At this level, start-up entrepreneurs may acknowledge the fact that a positive approach towards people and collective benefits is likely to entail long-term business performance. They have the chance to promote and consolidate sustainable business models from the onset of their businesses, based on value co-creation at the individual, group and community levels. Their founding vision may inspire people (e.g., employees, consumers and other categories of stakeholders) and may finally trigger an increasing market share in their firms and business sectors.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

As in any other research endeavour, the present study would benefit from further improvements.

Firstly, the conceptual and research model would be improved by the inclusion of more detailed and focused measures of the existing constructs. At this point, the items assigned to measuring TBL constructs addressed the entrepreneurs’ approaches (perceptions, attitudes, beliefs) and not the actual conducts. Thus, a future study would envision another multi-item framework targeting the behavioral aspects.

Secondly, the conceptual and research model would benefit from including other constructs and variables which were not considered in this point. We assume the fact that the current model takes into account only three major relationships between the latent variables and the consideration of other factors or moderating effects would refine the methodological design and the findings, e.g., the inclusion of controls in the structural model, like the company size, would be a pertinent endeavor in this respect.

Thirdly, testing the proposed hypotheses on larger samples or in the context of a certain business sector would make the analysis more accurate and would present a clearer outlook on the state of the art in the field.

Fourthly, the reiteration of the survey using a similar sample from Romania or from other developing countries in Europe would provide an additional test of our hypotheses (e.g., the relationship between the assumption of environment protection and business performance).

Finally, as far as the future constructs integrated in the research model are concerned, a theoretical development beyond the boundaries of the triple-bottom-line would be recommended as well as other factors (business strategy, business planning, etc.) which may account for an overall picture of sustainable entrepreneurship. Therefore, conducting confirmatory analyses would provide additional insights for the model fit among different models.