The Effects of Interdependence and Cooperative Behaviors on Buyer’s Satisfaction in the Semiconductor Component Supply Chain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

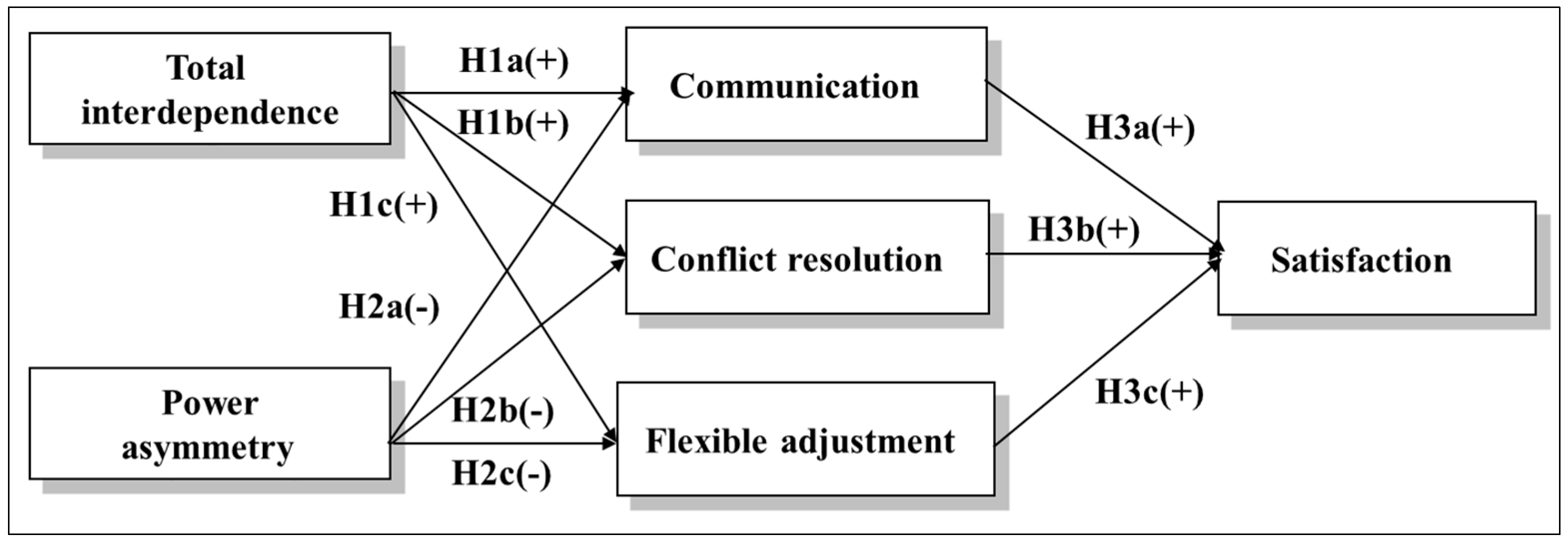

2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Conceptual Model

2.2. Total Interdependence and Cooperative Behaviors

2.3. Power Asymmetry and Cooperative Behaviors

2.4. Cooperative Behaviors and Buyer’s Satisfaction

3. Methodology

3.1. Target population and Data Collection

| Items | Types | No. | Cumulative % | Items | Types | No. | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business of focal companies | IC design house | 71 | 45.51% | Employees | Less than 100 | 8 | 5.13% |

| IC manufacturing | 9 | 51.28% | 100–200 | 25 | 21.15% | ||

| Packaging/Testing | 37 | 75.00% | 201–500 | 37 | 44.87% | ||

| Integrated Device Manufacturer (IDM) | 20 | 87.82% | 501–800 | 18 | 56.41% | ||

| Others | 19 | 100.00% | 801–1000 | 20 | 69.23% | ||

| Annual Sales | Less than 1 billion NT | 11 | 7.05% | 1001–2000 | 27 | 86.54% | |

| 1–10 billion NT | 43 | 34.62% | More than 2000 | 21 | 100.00% | ||

| 10–50 billion NT | 31 | 54.49% | Years in the current position | Less than 1 year | 8 | 5.13% | |

| 50–100 billion NT | 30 | 73.72% | 1–3 years | 27 | 22.44% | ||

| More than 100 billion | 41 | 100.00% | 3–5 years | 42 | 49.36% | ||

| Department | Purchasing | 47 | 30.13% | 5–8 years | 49 | 80.77% | |

| Supply chain management | 39 | 55.13% | More than 8 years | 30 | 100.00% | ||

| Production control/planning | 38 | 79.49% | Business of suppliers | IC manufacturing | 42 | 26.92% | |

| R&D | 24 | 94.87% | Packaging/Testing | 37 | 50.64% | ||

| Others | 8 | 100.00% | Designer service provider | 15 | 60.26% | ||

| Position | General manager | 17 | 10.90% | Mask provider | 7 | 64.74% | |

| Division manager | 41 | 37.18% | Equipment provider | 13 | 73.08% | ||

| Department manager | 52 | 70.51% | Chemical provider | 10 | 79.49% | ||

| Engineer or planner | 42 | 97.44% | Materials (probing care, lead frame, …) | 21 | 92.95% | ||

| Others | 4 | 100.00% | Others | 11 | 100.00% |

3.2. Questionnaire Design

| Constructs | Measurement Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Communication | Communication quality | CB1: Your communication with the supplier is timely. |

| CBC2: Your communication with the supplier is accurate. | ||

| CBC3: Your communication with the supplier is adequate. | ||

| CBC4: Your communication with the supplier is complete. | ||

| CBC5: Your communication with the supplier is credible. | ||

| Information sharing | CBI6: The supplier shares propriety information with us. | |

| CBI7: The supplier informs us in advance of changing needs. | ||

| CBI8: In this relationship, it is expected that any information which might help the other party will be provided. | ||

| CBI9: The parties are expected to keep each other informed about events or changes that may affect the other party. | ||

| Conflict resolution | Joint responsibility | CBJ1: In most aspects of the relationship, the parties are jointly responsible for making sure that tasks are complete. |

| CBJ2: Problems that arise in the course of this relationship are treated as joint rather than individual responsibilities. | ||

| CBJ3: The responsibility for making sure that the relationship works for both the other party and us is shared jointly. | ||

| Conflict resolution | CBR1: The discussions we have with the supplier in areas of disagreement are usually very productive. | |

| CBR2: Our discussions in areas of disagreement with the supplier create more problems than they solve. (R) | ||

| CBR3: Discussions in areas of disagreement increase the strength of our relationship. | ||

| Flexible adjustment | CBF1: A characteristic of this relationship is flexibility in response to requests for changes | |

| CBF2: When some unexpected situation arises, the supplier would rather work out a new deal than to hold each other to the original terms. | ||

| CBF3: It is expected that the supplier will be open to modifying their agreements of unexpected events occur. | ||

| Satisfaction with relationship | SA1: We are pleased with our relationship with the supplier. | |

| SA2: We wish more of our suppliers were like this one. | ||

| SA3: We would like our relationship with the supplier to continue in the future. | ||

| SA4: We are pleased to deal with the supplier. | ||

| SA5: We are pleased with the support and service provided by the supplier. | ||

| Buyer’s dependence | BD1: The reliability of delivery of the product from the supplier is important for an uninterrupted flow of manufacturing. | |

| BD2: We need the technological expertise of the supplier. | ||

| BD3: The product can not be bought from other suppliers. (R) | ||

| BD4: We will incur a high switching cost replacing the supplier. | ||

| Supplier’s dependence | SD1: We an important customer for the supplier, considering the volume of trade. | |

| SD2: The supplier needs the technological expertise of our company. | ||

| SD3: The products of the supplier can be sold to other customers. (R) | ||

| SD4: The supplier will incur high switching cost, replacing us by other buyers. | ||

| R: Reversed scored. | ||

| Constructs | Components and Measurements | References |

|---|---|---|

| Communication | Communication quality (five items) Information sharing (four items) | Mohr & Fearne [29] |

| Conflict resolution | Joint responsibility (three items) Conflict resolution (three items) | Maloni & Benton [12]; Johnson et al. [34] |

| Flexible adjustment | Three items | Johnson et al. [34] |

| Satisfaction | Five items | Lee [38] |

| Supplier’s dependence | Four items | Caniёls & Gelderman [25] |

| Buyer’s dependence | Four items | Caniёls & Gelderman [25] |

| Total interdependence | Four items | Buyer’s dependence + Supplier’s dependence |

| Power asymmetry | Four items | Buyer’s dependence − Supplier’s dependence |

| Demographic variables | Demographic data of respondent companies (seven items). |

4. Data Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

4.1. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

| Constructs | Factor Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE | Constructs | Factor Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Conflict resolution | ||||||

| CBC1 | 0.876 | 0.83 | 0.548 | CBJ1 | 0.871 | 0.77 | 0.616 |

| CBC2 | 0.857 | CBJ2 | 0.853 | ||||

| CBC3 | 0.861 | CBJ3 | 0.862 | ||||

| CBC4 | 0.897 | CBR1 | 0.891 | ||||

| CBC5 | 0.938 | CBR2 | 0.949 | ||||

| CBI1 | 0.887 | CBR3 | 0.884 | ||||

| CBI2 | 0.825 | Power asymmetry | |||||

| CBI3 | 0.752 | IA1 | 0.901 | 0.89 | 0.723 | ||

| CBI4 | 0.791 | IA2 | 0.922 | ||||

| Flexible adjustment | IA3 | 0.901 | |||||

| CBF1 | 0.747 | 0.94 | 0.511 | IA4 | 0.943 | ||

| CBF2 | 0.985 | Satisfaction | |||||

| CBF3 | 0.943 | ST1 | 0.913 | 0.88 | 0.674 | ||

| Total interdependence | ST2 | 0.834 | |||||

| TI1 | 0.884 | 0.90 | 0.656 | ST3 | 0.826 | ||

| TI2 | 0.802 | ST4 | 0.799 | ||||

| TI3 | 0.862 | ST5 | 0.854 | ||||

| TI4 | 0.834 | ||||||

| Latent Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Communication | 1.000 | |||||

| (2) Conflict resolution | 0.431 | 1.000 | ||||

| (3) Flexible adjustment | 0.381 | 0.421 | 1.000 | |||

| (4) Satisfaction | 0.269 | 0.347 | 0.366 | 1.000 | ||

| (5) Total interdependence | 0.347 | 0.484 | 0.307 | 0.161 | 1.000 | |

| (6) Power asymmetry | −0.156 | −0.330 | −0.328 | −0.113 | 0.142 | 1.000 |

| The square root of AVE | 0.740 | 0.785 | 0.715 | 0.757 | 0.801 | 0.850 |

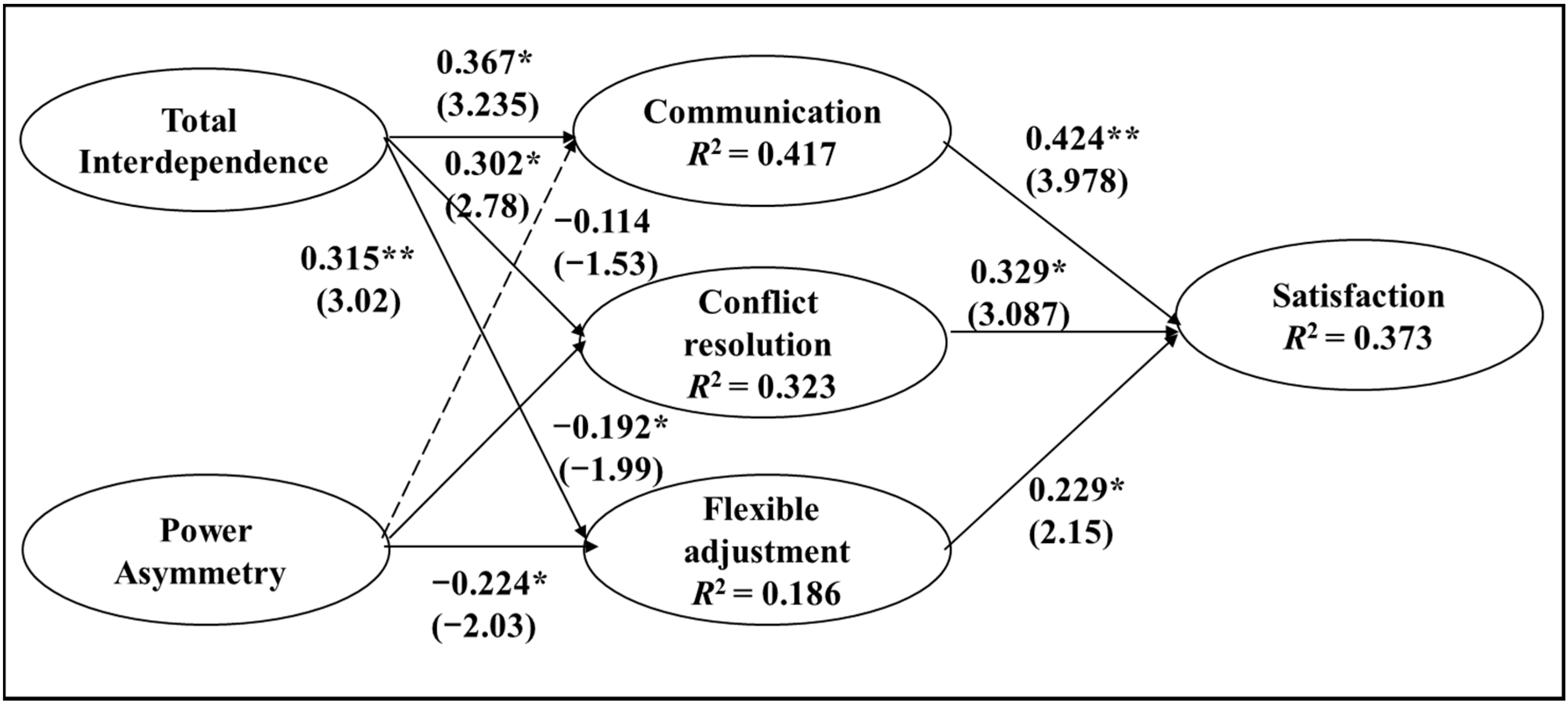

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

| Independent Construct | Mediator | Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | ||

| Total interdependence | 0.387 * | 0.327 * | 0.714 * | |

| Communication | 0.156 * | |||

| Conflict resolution | 0.099 * | |||

| Flexible adjustment | 0.072 | |||

| Power asymmetry | −0.374 * | −0.162 * | −0.536 * | |

| Communication | −0.048 | |||

| Conflict resolution | −0.063 | |||

| Flexible adjustment | −0.051 | |||

| Hypotheses | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | Total interdependence between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to communication. | Supported |

| H1b | Total interdependence between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to conflict resolution. | Supported |

| H1c | Total interdependence between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to flexibility in arrangement. | Supported |

| H2a | Power asymmetry between a buyer and its supplier is negatively related to communication. | Not supported |

| H2b | Power asymmetry between a buyer and its supplier is negatively related to conflict resolution. | Supported |

| H3c | Power asymmetry between a buyer and its supplier is negatively related to flexibility in arrangement. | Supported |

| H3a | The extent of communication between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to buyer satisfaction. | Supported |

| H3b | The extent of conflict resolution between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to buyer satisfaction. | Supported |

| H3c | The extent of flexibility between a buyer and its supplier is positively related to byer satisfaction. | Supported |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, A.; Gudmundsson, D.; Nurani, R.K.; Seshadri, A.; Shanthikumar, J.G. Fabless-Foundry partnership: Models and analysis of coordination issues. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 1999, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Iijima, J. Linkage between strategic alliances and firm’s business strategy: The case of semiconductor industry. Technovation 2005, 25, 315–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Iansiti, M. Experience, Experimentation and the Accumulation of Knowledge: The Evolution of R&D in the Semiconductor Industry. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 809–825. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, Y. IBM partners for consumer SOI development. Electronic Engineering Times, 8 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W. The effect of supply chain integration on the alignment between corporate competitive capability and supply chain operational capability. Int. J. Oper. Product. Manag. 2006, 26, 1084–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.; Handfieldb, R.B.; Ragatz, G.L. Supplier integration into new product development: Coordinating product, process and supply chain design. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Narus, J. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahadev, S. Exploring the role of expert power in channel management: An empirical study. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Power-dependence relations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, W.C.; Maloni, M. The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloni, M.; Benton, W.C. Power influences in the supply chain. J. Bus. Logist. 2000, 21, 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Hoi, J.; Yeung, Y. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.B.; Lusch, R.F.; Nicholson, C.Y. Power and relationship commitment: Their impact on marketing channel member performance. J. Retail. 1995, 71, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, B.A.; Dwyer, F.R. Power, bureaucracy, influence, and performance: Their relationships in industrial distribution channels. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 32, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Talias, M.A.; Leonidou, C.N. Exercised power as a driver of trust and communication in cross-border industrial buyer-seller relationship. J. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaseshan, B.; Yip, L.S.C.; Pae, J.H. Power, satisfaction and relationship commitment in Chinese store-tenant relationship and their impacts on performance. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S.J.; Gassenheimer, J.B.; Kelley, S.W. Cooperation in Supplier-Dealer Relations. J. Retail. 1992, 68, 174–193. [Google Scholar]

- Olhager, J.; Selldin, E. Supply chain management survey of Swedish manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 89, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vaart, T.; van Donk, D.P. A critical review of survey-based research in supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Y.; Chiang, C.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Tu, H.F. The influencing factors on commitment and business integration on supply chain management. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2004, 104, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, T.; Piskorski, M.J. Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Admin. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, G.L. On the measurement of interfirm power in channels of distribution. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Scheer, L.K.; Steenkamp, E.M. The effects of supplier fairness on vulnerable resellers. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.J.; Gelderman, C.J. Power and interdependence in buyer supplier relationships: A purchasing portfolio approach. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, U.Y.; Kotzab, H. Supply chain management: The integration of logistics in marketing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.; Fearne, A. The impact of supply chain partnerships on supplier performance. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.; Spekman, R. Characteristics of partnership success: Partnership attributes communication behavior and conflict resolution techniques. Strat. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancastre, A.; Lages, L.F. The relationship between buyer and a B2B e-marketing place: Cooperation determinants in an electronic market context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadas, E.; Dwyer, F. An examination of organizational factors influencing new product success in internal and alliance-based process. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablin, F.L.; Putnam, K.; Roberts, L. Porter, Handbook of Organizational Communication; Sage Publication: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ragu-Nathan, B.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Raob, S.S. The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance. OMEGA 2006, 34, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P.; Daft, R.L. The information environments of organizations. In Handbook of Organization Communication; Jablin, F., Putnam, L., Roberts, K., Poters, L., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, D.A.; McCutcheon, D.M.; Stuart, F.I.; Kerwood, H. Effects of supplier trust on performance of cooperative supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 21, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jap, S.M. Pei-expansion efforts: Collaboration processes in buyer-supplier relationship. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J. Power measurement. Eur. J. Purchas. Supply Manag. 1996, 2, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. The power of power in supplier-retailer relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y. Power, conflict, and satisfaction in IJV supplier in Chinese distributor channels. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Industrial Economics & Knowledge Center (IEK). 2013 Semiconductor Year Book; Industrial Economics and Knowledge Center: Taipei, Taiwan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.R.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Weitz, B.A. Determinations of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Mark. Sci. 1989, 8, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapiran, G.P.; Hogarth-Scott, S. Are cooperation and trust being confused with power? An analysis of food retailing in Australia and the UK. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, J.D.; Kumar, N.; Stern, L.S. Examining the impact of destructive acts in marketing channel relationships. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 28, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, F.R.; Schurr, P.H.; Oh, S. Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pai, F.-Y.; Yeh, T.-M. The Effects of Interdependence and Cooperative Behaviors on Buyer’s Satisfaction in the Semiconductor Component Supply Chain. Sustainability 2016, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010002

Pai F-Y, Yeh T-M. The Effects of Interdependence and Cooperative Behaviors on Buyer’s Satisfaction in the Semiconductor Component Supply Chain. Sustainability. 2016; 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePai, Fan-Yun, and Tsu-Ming Yeh. 2016. "The Effects of Interdependence and Cooperative Behaviors on Buyer’s Satisfaction in the Semiconductor Component Supply Chain" Sustainability 8, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010002