5.1. Basic Values

As a first step in the analysis, a shortened version of [

47] value-inventory scale is applied for assessing the importance the respondents assign to basic values, as well as how they make priorities among them. The value-inventory scale arranges a set of 10 motivational value-types based on the inherent conflict and compatibility between each type’s organizing value-items and have undergone numerous empirical tests confirming its validity for categorizing those values that individuals employ as guiding principles in life. The results from this inventory are therefore believed to provide a reliable first indication of how the respondents rate the importance and significance of fundamental normative principles, such as loyalty, power, security, and freedom. Furthermore, following the hierarchical structure of the values-construct, basic value priorities have been shown as lying at the core of the individuals’ formation of beliefs on a wide range of more specific topics, for instance political orientations and environmentalist predispositions [

41,

48,

49]. Thereby, how the respondents prioritize among basic values is believed to be of additional significance as it provides relevant first-hand information also on which type of issues that are the most salient for the individual, which assists her interpretation of the outside world, and will guide her formation of empirically oriented beliefs and policy-preferences.

In completing the value-inventory scale, the respondents in the two samples were asked to indicate the degree to which 20 indicator-values functioned as, following [

12], guiding principles in their life. A 9-point scale, ranging from −1 (opposed to my values) to 7 (of supreme importance), was provided for marking their answers. The mean score for all value-items from these samples are illustrated in

Table 2 below, along with any significant changes in the importance attributed a value-item between the two samples. This initial inventory of basic value-priorities conveys that the respondents in both samples attribute the highest importance to the two value-items F

amily security and F

reedom. At the very bottom of the list are the value-items S

ocial power and A

uthority, both of which enjoys a markedly low support. A further six items, distributed over all positions in [

46]’s motivational continuum also receive a mean score over 5.0, which point towards their overall importance for the respondents. Among these is the value-item of specific relevance for the policy-domain studied in this thesis:

protected environment. This goes to show that, although not the most important, a general interpretation of environmental protection can nevertheless be assumed a salient issue with the respondents.

Table 2.

Value-items (mean score).

Table 2.

Value-items (mean score).

| Value-item | Mean score (N = 1189–1207) |

|---|

| Broad-Minded (being tolerant towards different ideas and beliefs) (U) | 4.68 |

| Protected environment (preserving diversity in the ecological system) (U) | 5.11 |

| Social justice (correcting injustice, care for the weak) (U) | 5.21 |

| Helpful (working for the welfare of others) (B) | 4.52 |

| Loyalty (faithful to one’s friends and group) (B) | 5.54 |

| Wealth (material possessions, money) (P) | 3.31 |

| Social power (control over others, dominance) (P) | .54 |

| Authority (having the right to lead or command others) (P) | 1.04 |

| Influential (having an impact on people and events) (A) | 3.31 |

| Successful (successful, achieving goals) (A) | 4.13 |

| Self-discipline (self-restraint, resistance to temptation) (C) | 3.90 |

| Obedience (meeting one’s obligations) (C) | 5.20 |

| Social order (a stable society) (Sec) | 5.31 |

| Family security (safety for loved ones) (Sec) | 6.36 |

| Respect for tradition (preservation of time-honored customs) (T) | 3.48 |

| Freedom (freedom to think and act) (SD) | 6.17 |

| Independence (self-reliant, self-sufficient) (SD) | 5.20 |

| Creativity (being unique, imaginative) (SD) | 4.15 |

| Curiosity (interest in everything, exploring) (SD) | 4.18 |

| A varied life (a life filled with challenge, novelty and change) (Sti) | 3.87 |

However, analyzing how people rate single value-items provides only limited information about their overall value-orientation. This is due to several causes, not the least since the generality of the value-items opens up for a range of subjective interpretations on their meaning. In this sense, a value-item might be described as a floating signifier, since it is ascribed different meanings by different individuals in different contexts and can thus be fully understood only when connected to a chain of other items. In order to provide a more comprehensive analysis of people’s basic priority of values we need to consider how single value-items form coherent value-domains, and take into account the compatibility and conflict between different single values that these domains convey. In particular, following the emphasis of a non-territorial, asymmetrical social justice as a core principle underpinning the notion of EC, it seems reasonable to apply the respondents’ priority among core values for considering how they inform judgements concerning distributive justice. In other words, which groups or entities are singled out for their welfare being of significant priority?

To their essence, values addressing welfare-priorities have a strong political-ideological bearing as they underpin understandings of economic egalitarianism, and guide the individual to different political preferences on this issue [

14,

41]. Within the environmental policy domain, how the importance between personal and social context outcomes is rated is of course of significant relevance. One reason is that the attainment of positive environmental outcomes might entail both economic and social costs for the individual (hence the framing of them as collective-action dilemmas), another that environmental problems may be conceptualized as threats to a number of different groups (self, in-group, out-group) the significance of which is determined by these values. The egoism/altruism demarcation that this value-dimension elucidates has therefore been widely applied to characterize both the sources of the environmental problem as well as the necessary change of individuals’ consciousness in the process of amending it [

2]. In this endeavor, [

5,

50] highlights the divide by distinguishing between the motivational differences behind the two roles of altruistic citizen and the self-regarding consumer. Values expressing priorities of distributive justice thus lay at the core of how the relationships both between human beings and nature (e.g., a moral sphere expanded also to other species or entities), and between state and individual (e.g., non-territorial or global duties for the citizen) are understood.

However, merely making the distinction between egoism and altruism do not adequately capture the full complexity of an individual’s value-system. Although the S

elf E

nhancement-cluster (see

Table 2) presents a rather straight-forward orientation towards personal benefits, altruistic motivations might be both narrow and broad in scope. Altruism might thus incorporate a preference for welfare on a global (perhaps even non-human or intergenerational) scale, as suggested by EC, as well as for prioritizing the welfare of primary groups. By not discriminating between these two interpretations of altruism, the egoism/altruism-divide becomes a rather blunt instrument for reliably establishing whose welfare the respondents assign priority to [

45]. This highlights the need for making a further demarcation of value-domains expressing a prominent universal and narrow social scope respectively. In order to nuance the territorial breadth of altruism, a triarchal classification of motivational domains is constructed as suggested by [

51,

52,

53] and [

48]. The three motivational value domains—here termed

Universal,

Social and

Self-Enhancement—collect values that indicate both how an individual prioritizes various motivational value types (e.g., power, benevolence, universalism, conformity), and how he or she defines proper distribution of justice. As such, these three domains can be used to indicate both a respondent’s motivation to pursue, or at least accept, activities with particular consequences [

48].

S

elf-enhancement is a higher-order value type elaborated on by [

47], and contains motivations for the individual to pursue “personal interests (even at the expense of others)”. This self-regarding focus is consistent with what other studies have classified as an economic [

53], egoistic [

48] or egocentric [

52] value orientation, focusing on outcomes that maximize self-interest rather than the interest of the larger community. So is [

50]’s characterization of the motives inherent in the consumer role, which thereby places the values in this domain directly opposite those of the broad-scope altruistic ecological citizen. S

elf-E

nhancement instead guides the formation of attitudes in a way that makes the individual less inclined to take action or respond positively to policies aimed at increasing environmental protection, if these entail some form of individual cost. At the same time, these individuals are more inclined to accept policies promising some form of personal benefit in exchange for individual action [

53].

The S

ocial and a U

niversal value-domains are computed using value-items which accentuate the preference either for “welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact” or for “welfare of all people and for nature” [

54]. This makes them similar, but not entirely correspondent, to those value-orientations termed either Biospheric and Social-Altruistic [

47], or Ecocentric and Homocentric [

51]. An important difference from these categorizations is the less pronounced demarcation between ecocentrism and anthropocentrism in our value-orientations. Also universalism has an anthropocentric orientation evident by, for instance, the inclusion of social justice and broad-mindedness as two of its motivating values. We should, however, remember that it is neither expected that the ecological citizen is anything but a shallow-ecologist or a weak-anthropocentric [

2], thus corresponding to the value base of universalism. Our domains could also be applied as providing an indication of the respondent’s motivation to pursuit, or at least accept, activities with a particular set of consequences directed towards particular groups or entities [

48]. A S

ocial value-domain indicates prioritising a sense of belongingness and acceptance from others as well as a pursuit of goals which enhances the welfare of close others as a means to this end. This value-domain therefore incorporates items which emphasizes the welfare of the in-group and motivates the individual to restrain actions that are likely to upset others and violate social norms [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. This also highlights the connections between a narrow scope of altruism and more collectivist cultures as suggested by [

47]. Although with an altruistic base, the priority of care for close others expressed by this value-domain is not entirely in line with the non-territorial, intergenerational moral sphere linked to EC; instead it reflects a notion of territoriality when rank-ordering the welfare of different groups, where priority is granted those individuals who share membership in a community either taking the shape of the family or of some other form of in-group. In this way, a S

ocial value-domain thereby expresses a significant principle on which traditional ideas of citizenship (or state/individual relations) are constructed: the moral relationship among people within the same politically defined society. Thus, from a perspective of environmentalism, individuals holding a strong social value-orientation are expected not to support environmental protective policies in those instances where these are understood as having short-term negative consequences for close others, and actively support environmental claims if they are perceived as beneficial for the own in-group and/or for their own social status [

53].

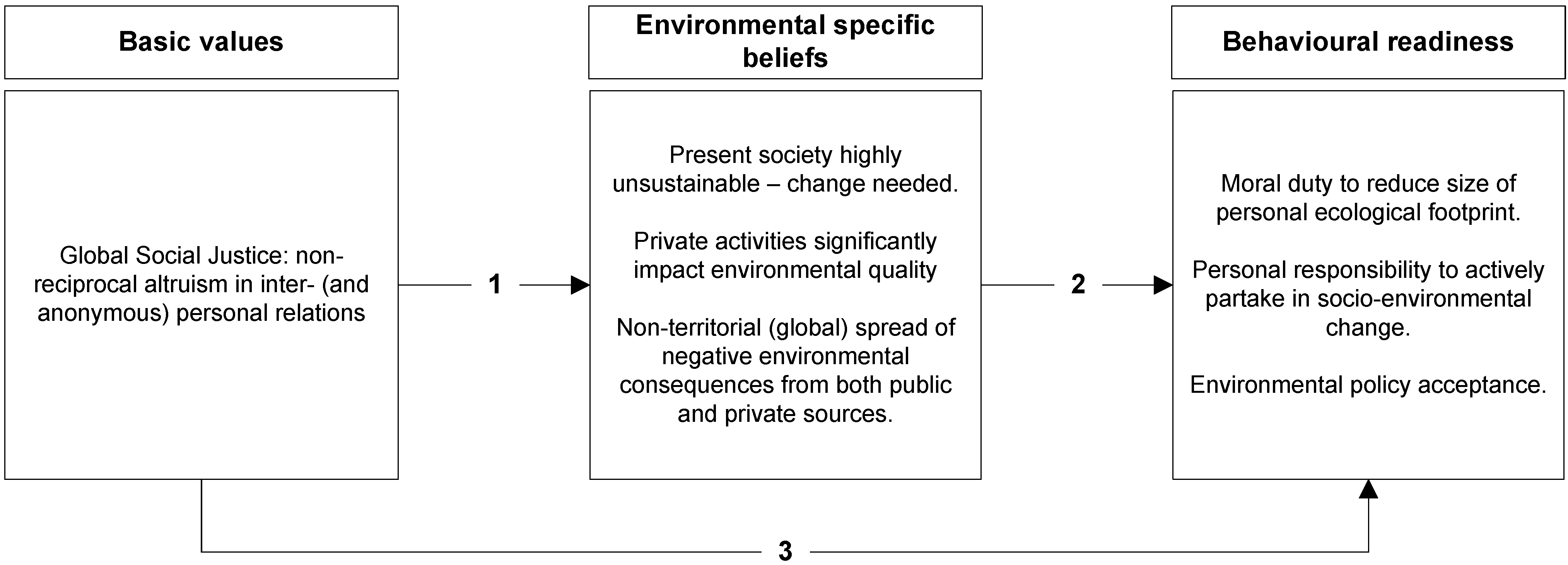

In contrast, people holding a U

niversal value-orientation are believed not to make any sharp distinctions between members of the in- and out-groups when developing criteria for welfare distribution. The U

niversal domain is most closely associated with the morality and non-territoriality of the post-cosmopolitan ecological citizen, as we remember that EC applies the metaphor of the ecological footprint and the inter-personal relationships this generate as a starting-point [

1,

2]. These defining characteristics correspond rather well with the value-items included in the U

niversal value-domain, and their recognition of global interdependency as well as of distant or anonymous relationships without any form of in-group contacts (e.g., [

46]) are clearly distinguished from the altruistic value-items within the S

ocial domain. The strong connections between universalism and pronounced environmental attitudes should therefore come as no surprise. People holding it as their dominating value-domain are expected to be motivated by the perceived benefit or cost to the world at large, including the non-human environment, not based on the short-term costs facing either the own person or close others [

47,

53]. It is also within this value domain that the strongest connections to pronounced environmental attitudes and norm activation resulting in PEB are observed [

23,

48].

In

Table 3, the means, standard deviations and scale-reliabilities for the three value-domains are outlined. The indices were created by summing up the responses to each included value item and dividing by the total number of items within the domain. Scale-reliability (Cronbach’s α) was also generated for each value domain. In both samples, the reliabilities for the value-domains range between 0.62 and 0.76, which are considered reasonably high enough to generate indices for each.

Table 3.

Welfare of greatest concern.

Table 3.

Welfare of greatest concern.

| | Mean | Standard deviation | Scale reliability (Cronbach’s α) |

|---|

| Self-Enhancement | 2.47 | 1.20 | 0.76 |

| Social | 4.54 | 1.09 | 0.67 |

| Universal | 5.00 | 1.23 | 0.62 |

According to our results, when discriminating between altruism with a narrow and a broad scope, respondents attribute higher importance to the latter. This is a clear demonstration of the fact that also non-territorial relationships are granted significant weight when developing personal criteria for distributive justice. However, the high mean-scores of two altruistic domains suggest that respondents, to some extent, attribute importance to both a broad as well as a narrow interpretation of altruism. It is also perfectly reasonable to argue that a person can have multiple preference orderings and therefore show different preferences in different contexts [

55]. Sometimes, however, individuals are faced with situations where value trade-offs between two or more conflicting values domains become unavoidable [

56]. It is in these conflict situations that a person’s hierarchical ordering of values is believed to be of great importance, serving as a guide for choosing among different attitudinal or behavioral strategies [

57]. Thus, since we are dealing with individuals’ predisposition to act (or accept policies) in a context full of potential conflicts between personal, social and universal outcomes, it seems reasonable to consider how people rate the three motivational value domains relative to each other; how large is the share of potential ecological citizens in the sample?

To determine the extent to which the respondents should be assigned one of the three value domains as being dominant (and by inference the extent to which the respondents hold mixed or uncertain value domains), we applied two criteria [

53]. First, each respondent’s mean-score for his or her dominant value-domain should be higher than his/her mean-scores for (any one of) the opposing value-domain(s). Second, to be considered dominant, the respondent’s own mean-score for this value-domain also should be above the mean-score for the same value-domain calculated among the total population. In this way, we argue that the strength of the respondents’ priority of one value domain is adequately displayed.

Table 4 illustrates the distribution of dominant value domains.

Table 4.

Dominant value-domains concerning welfare (% of respondents).

Table 4.

Dominant value-domains concerning welfare (% of respondents).

| Value-domain | Strong | Weak |

|---|

| Self-Enhancement | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Social | 22.7 | 32.9 |

| Universal | 40.9 | 61.3 |

| Uncertain/Mixed | 34.9 | 4.3 |

Overall, these results suggest that altruism with a broad scope is firmly established among the respondents with over 40% holding Universal as dominant value-domain. This, again, suggests that the distinction between the welfare for members of the own in-group and for others, is not as sharp among the respondents. Consistent with EC, the groups whose welfare is of greatest concern are thereby identified based on other criteria than a predetermined, territorially bound membership and the moral community therefore stretched out as to encompass also people and entities with whom no personal contacts exists.

Although a U

niversal orientation certainly is dominant among the respondents, it should nevertheless be noted that the S

ocial value-domain was possible to assign as weakly dominant among one-third of the respondents. This, however, could indeed be interpreted as a movement in this direction. In EC-theory, social-altruism is considered a first way-station on the road towards a transformed ecological consciousness, as: “once the shift from “self-regarding” individual to “other-regarding” citizen has been made, it is a much smaller step to extend that public concern to foreigners, future-generations and non-human nature” [

58].

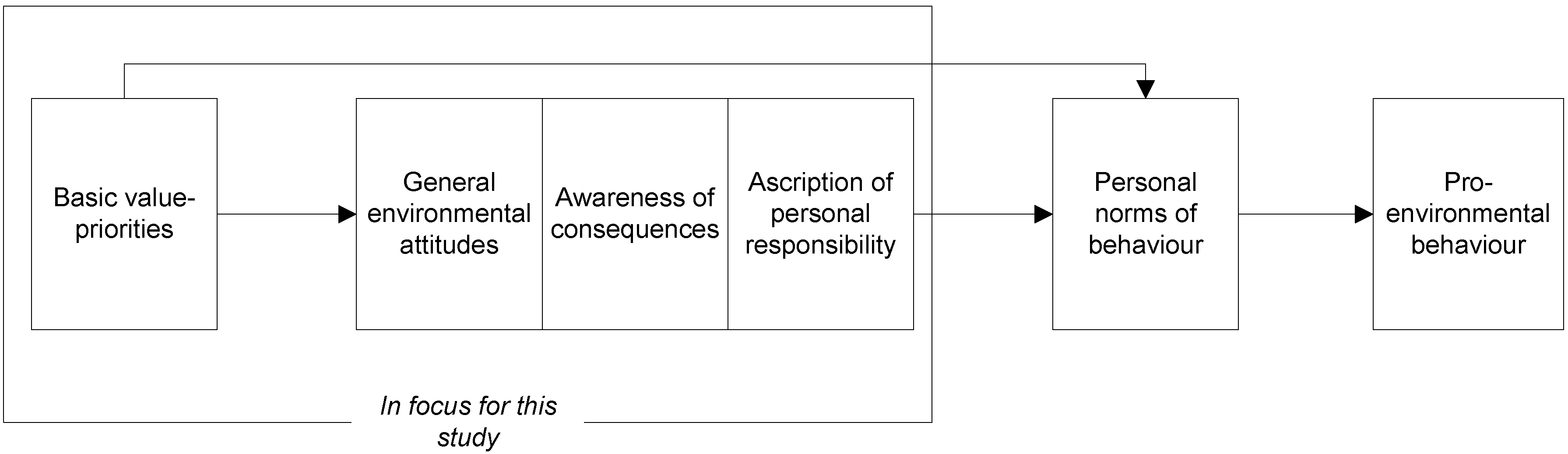

5.2. Environmental Beliefs

So far, we can conclude that altruism with a broad scope is of significant importance. But how does this distribution of general value preferences translate into a formation of environmental beliefs? Previous research has demonstrated the connection between values and attitude formation, concluding that personal values function as a backstop for attitudes on more specific matters, thus indicating how an individual responds to e.g., new public policies. This is certainly true also for environmental issues, where values are thought to affect both general environmental attitudes and a person’s predisposition to PEB. Investigating also the extent to which the value domains explained above guide respondents’ support of an environmental worldview therefore seems highly relevant in the endeavor of scrutinizing the existence of the ecological citizen.

To determine how the respondents rate the importance of specific environmental beliefs, we used the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale [

59]. This scale has been widely used to measure people’s pro-environmental orientations, and findings from such studies suggest a significant relationship between NEP ratings and both behavioral intentions and actual behavior [

48,

49]. Therefore, individuals’ NEP ratings are taken to reflect their inclination to form pro-environmental attitudes on a wide range of issues, and, by inference, their probable responses towards policies addressing these issues [

59]. The NEP scale aims at capturing a person’s view on five facets believed to form the core of environmental concern, and serves to tap individuals’ understanding of policy-specific issues, e.g., the overall causes and seriousness of environmental problems and the prospect for society to solve environmental problems. In line with the notion of EC, the NEP scale thereby indirectly describes the tension between new and old politics e.g., by accentuating universal care for others and the need for comprehensive lifestyle changes and new politics in the form of increased individual participation, and by deemphasizing technological optimism and market solutions [

60].

In the survey, we asked the respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with 15 statements about the environment. The response categories range from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Whereas agreement indicates a worldview in line with the NEP scale for eight of the statements, seven statements, marked (-), were worded so that disagreement agrees with the NEP scale. Calculating mean NEP scores necessitates reversal of the ordering of these seven items to make high scores correspond to a stronger pro-environmental orientation than low scores. Based on the connection between universal values and environmental attitudes proposed above, we hypothesize further that individuals holding a strong

universal orientation display a high NEP score in total and a low score for the seven items marked (-).

Table 5 presents the survey results, including the significance of the respective relationships between the mean scores of each of the three value domains and the NEP-items.

We note that both samples demonstrate a fairly high internal consistency (α = 0.78) for the 15-item NEP-scale. This validates the creation of a NEP-index incorporating all of these items. When doing so, it is furthermore possible to conclude that the respondents overall lend a strong support for the NEP-scale as a whole (mean NEP-score = 3.67). Overall, they display both a high sense of environmental risk awareness and an acknowledgement of the place of human beings

in nature rather than

above it. Respondents prioritizing the Universal value domain display the most positive disposition towards the NEP worldview (r = 0.254,

p = < 0.01, significant negative correlations is displayed for both S

ocial and S

elf-enhancement), in particular regarding a reported awareness that current practices within developed countries imply significant negative consequences for the natural environment. At the other end of the spectrum, respondents holding strong self-regarding values are significantly less inclined to support the NEP worldview. These values are instead strongly connected to the worldview of the Dominant Social Paradigm [

49,

60], which implies a belief in the privileged status of human beings (pronounced anthropocentrism) and a strong trust in the market’s and technology’s ability to solve problems of environmental degradation and resource depletion. Nevertheless, due to the marginality of this group among the respondents, we conclude that people in general agree on the basic causes of the environmental problem and express a need both to rethink the human beings/nature relationship and to move beyond short-term technological inventions as the primary tool for reaching sustainability. This clearly points towards the environmentally protective agenda linked to EC.

Table 5.

Mean NEP score (including significance for dominant value domain).

Table 5.

Mean NEP score (including significance for dominant value domain).

| | Universal | Social | S-E | Total |

|---|

| NEP total (α = .78) | 3.83*** | 3.59* | 3.33*** | 3.67 |

| Possibility of an Eco-crisis | | | | |

| 4.36*** | 4.11* | 4.00 | 4.17 |

| 3.89*** | 3.57** | 3.75 | 3.70 |

| 2.20*** | 2.76*** | 3.08*** | 2.55 |

| Rejection of Exemptionalism | | | | |

| 2.77*** | 2.95** | 3.50*** | 2.87 |

| 4.30*** | 4.12** | 3.92** | 4.20 |

| 2.62*** | 2.93*** | 3.00 | 2.79 |

| Reality of Limits to Growth | | | | |

| 3.51 | 3.48 | 3.85 | 3.49 |

| 3.90** | 3.91** | 4.00 | 3.82 |

| 3.87*** | 3.60** | 3.54 | 3.70 |

| Antianthropocentrism | | | | |

| 1.83*** | 1.97 | 2.85*** | 1.99 |

| 4.24** | 4.27 | 3.38*** | 4.15 |

| 1.88*** | 2.33*** | 3.23*** | 2.14 |

| Fragility of Nature’s Balance | | | | |

| 4.03*** | 3.87 | 3.54*** | 3.89 |

| 1.75*** | 2.33*** | 2.46** | 2.10 |

| 4.29*** | 4.04*** | 3.67*** | 4.14 |

We remember that the necessity for individuals to take on an increased environmental responsibility is the blurring of public and private domains, in that private actions always have also public (and global) consequences and therefore should be granted political connotations. The ecological citizen thus recognizes that also everyday private activities can have severe environmental effects, for the local as well as the global community. To probe deeper into the EC-supportive beliefs among the respondents, we asked the respondents to indicate whether, and to which degree, they agree or disagree with statements addressing the seriousness and direction of the environmental threat posed by three daily household-activities.

Table 6 illustrates the respondents’ understanding of problem seriousness.

Table 6.

Seriousness of problem—specific activities (% of respondents).

Table 6.

Seriousness of problem—specific activities (% of respondents).

| | Completely agree | Partly agree | Unsure | Partly disagree | Completely disagree | N |

|---|

| Unsorted household waste is such a serious problem that measures need to be taken immediately | 18.3 | 28.8 | 34.7 | 11.4 | 6.7 | 1,224 |

| Air pollution from private car use is such a serious problem that measures need to be taken immediately | 25.2 | 26.3 | 30.9 | 11.2 | 6.3 | 1,213 |

| The consumption and production of non eco-labelled goods is such a serious problem that measures need to be taken immediately | 11.1 | 20.0 | 42.6 | 15.5 | 10.8 | 1,219 |

It stands clear that many respondents consider the adverse environmental effects of these daily private-sphere activities to be significant. Together with the strong support of a U

niversal value-domain, the above results thereby strengthens the conclusion that a significant share of the respondents hold beliefs rather close to what is expected of an ecological citizen. Furthermore, exploring perceptions of one’s own personal contribution to the environmental problem is one common method for elucidating the strength of a person’s ascription of responsibility (see

Figure 2). Following the connection between predictors of pro-environmental behavior outlined in the VBN-theory, it seems reasonable to assume that recognizing private activities as contributing to an adverse environmental situation also indicates the presence of beliefs suggesting the ability, and perhaps even duty, of individuals to refrain from such activities.

Our analysis of value domains among the Swedish public has so far demonstrated that values and environmental attitudes related to EC enjoy rather strong support. Taken together with the respondents’ overall high NEP score, it seems reasonable to conclude that a significant share of people in general indeed hold the core values that not only imply a predisposition to support or engage in comprehensive individual environmental action, but also induce a sense of “being green in doing them” [

33].

5.3. Behavioral Readiness

Our final inquiry deals with the respondents’ self-reported willingness to accept policy-instruments that promote pro-environmental contributions from individuals, and with the respondents’ willingness to change behavior in a more pro-environmental direction. Note that the aim here is to shed light on the level of support for individual environmental activities and policy instruments presently debated in society. The questions do not capture the entire spectrum of possible policy measures, nor do they indicate respondent willingness to express environmental awareness in new and innovative ways. It is also necessary to acknowledge that the value-behaviour connection is unavoidably distorted by other factors such as context, resource constraints and personal habits [

17]. Hence, rejection of a certain policy measure, or failure to comply with an activity in practice, may be due to other reasons than rejection of the core values on which it rests. Although we firmly believe that the results presented in the rest of this section indicate that the respondents overall are willing to accept new policy instruments and increased environmental responsibility, they should still be interpreted with caution. The question posed is whether an orientation towards other-regarding values also drives the practice of EC. If tangible measures that have actual implications for the respondents’ social and economic status are presented, how are their reported pro-environmental disposition affected?

First, is the Swedish public willing to take on a greater individual environmental responsibility? In the survey, respondents were asked to rate their willingness to increase pro-environmental contributions through three different measures that are currently suggested as important household contributions on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Table 7 summarizes the responses, together with a Willingness-to-Change (WTC) index combining the three items. The significance of the relationship between the mean value of the WTC and the dominant value-domain is also displayed.

Table 7.

Mean value for willingness to change behavior.

Table 7.

Mean value for willingness to change behavior.

| | Universal | Social | S-E | Total |

|---|

| I am willing to increase my sorting of household waste in order to reduce the negative effects on the environment. | 4.33*** | 4.00 | 3.38 | 4.06 |

| I am willing to reduce my car use in order to reduce the negative effects on the environment. | 3.39*** | 2.93 | 2.42 | 3.04 |

| I am willing to increase my purchase of eco-labeled goods in order to reduce the negative effects on the environment. | 4.08*** | 3.58*** | 3.46 | 3.74 |

| Willingness to Change index (α = .66) | 3.90*** | 3.50 | 3.06 | 3.59 |

In all three value domains respondents reported a relatively strong willingness to increase their personal pro-environmental efforts. Not surprisingly, activities with little conflict between environmental and socio-economic outcomes (e.g., household waste management) enjoy stronger support than activities with more apparent conflicts involved (e.g., car use and green consumption). Here it should be noted that the relatively lower willingness among respondents to reduce car use may also partly be explained by the significant structural and habitual difficulties constraining the transition from private car to public transport [

61]. Also as predicted, respondents’ WTC varies with their value priorities; having universal values clearly implies a higher WTC in all three types of behavior. Similarly, although not statistically significant, respondents prioritizing self-regarding values reported less overall inclination to change behavior, which is consistent with previous research on the connection between collectivism, self-enhancement and pro-environmental norms of behavior [

46]. These results further support the proposition that ‘citizen-values’ are significant drivers of personal readiness to act in environmental matters and that the theory of EC therefore can be valuable as an approach to attain individual environmental responsibility.

Second, respondents were asked to state the extent to which they supported an introduction of new policy instruments aimed at promoting change in household waste management, patterns of transportation and private consumption. The scale used ranged from −2 (completely against) to 2 (completely for), with 0 meaning ‘neither for nor against’. The self-reported willingness to accept new policy instruments is illustrated in

Table 8.

Table 8.

Willingness to accept new policy instruments.

Table 8.

Willingness to accept new policy instruments.

| | Universal | Social | S-E | Total |

|---|

| Information campaign (Household waste management) | 0.88*** | 0.74 | 0.31*** | 0.71 |

| Weight-based system (Household waste management) | 0.59*** | 0.29* | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| Municipal Waste collection system | −0.15*** | −0.63** | 0.00*** | −0.38 |

| Information campaign (car use) | 0.35*** | −0.07*** | −1.38* | 0.04 |

| Raised tax on petrol | −0.53*** | −1.14*** | −1.15 | −0.90 |

| Increased Public transport availability | 1.33*** | 0.96** | 0.92 | 1.07 |

| Information campaign (Green consumption) | 0.69*** | 0.26** | −0.08*** | 0.41 |

| Introduce Tax on non eco−labeled products | 0.23*** | −0.33*** | −0.38 | −0.14 |

As

Table 8 illustrates, the respondents on average are considerably less supportive of the push measures (

i.e., policy instruments in the shape of fiscal disincentives) included in the survey. Consequently, negative results are displayed for the introduction of taxes on petrol (discouraging private car use) and non eco-labeled goods (encouraging green consumption). Respondents are also negative to the introduction of a municipal waste collection system where households would no longer have to transport their waste to drop-off stations themselves as is common practice in Sweden today. The respondents who hold a strong social value domain (followed by those holding a strong universal value domain) are the most negative to an introduction of such a system. It might thus be hypothesized that the practice of taking household waste to the drop-off station is perceived as a highly valued activity in itself. Doing one’s share by sorting household waste might be understood as an activity that produces a notable outcome for individuals with a strong pro-environmental orientation, or as an activity that demonstrates conformity with what is believed to be a strong social norm. Persons holding strong universal or social value domains could therefore be anticipated to be particularly sensitive to this type of motivation. Regarding the relatively low willingness to decrease private car use, there is overall weak support for both a raised tax on petrol and for an information campaign aimed to encourage alternative modes of transport. Again, if habits and structures are the main constraints for car-use reduction, then informative instruments will not address the experienced difficulties properly.

The strongest overall support is displayed for the introduction of policy instruments that facilitate individuals to increase their participation (pull measures). Hence, there is overall support for information campaigns aimed to encourage pro-environmental behavior, and, in particular, for improved public transport system through increased availability (more departures) and lower prices. The relatively weaker support for many of these instruments among respondents with self-enhancement as their dominant value-domain might be due to the fact that our questions specified that the information campaigns would be financed by municipal tax revenues.

These results suggest a significant relationship between the universal value domain and the reported willingness to accept all proposed policy instruments. e.g., respondents prioritizing this value domain are more inclined to support the introduction of new policy instruments, including one of the push measures (taxes on non eco-labeled goods). This further supports the assumption that the values inherent in this domain are of considerable importance for the acceptance of personal environmental responsibility. In comparison with respondents with the self-enhancement or the social value-domains, respondents holding what we here characterize as the value base of ecological citizens are clearly more willing both to accept policies aimed to transform behavioral patterns and to change their own behavior.