Social Franchising Model as a Scaling Strategy for ICT Reuse: A Case Study of an International Franchise

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Franchising as A Strategy for Scale Social Enterprises

2.2. ICT Reuse Industry Characteristics

- Collection systems often do not allow for the proper handling of reusable products;

- Consumers often store products for long periods before returning them, and thus any potential economic value is lost;

- Access to the waste stream can be restricted by vested interests;

- Permitting and licensing arrangements can be restrictive for small operators;

- Training and up-skilling for employees is inaccessible; and

- The activities of illegal operators give the business a bad reputation.

2.3. Analytical Framework of Identified Success Factors in the Literature for Developing Social Franchise in the Area of ICT Reuse

3. Methodology

- To investigate business experience and resources needed for the establishment of the case study organization.

- To investigate which are key success factors of the operational model of the case study organization.

- To investigate what the key characteristics for successful member of the case study organization are.

- To investigate if in the case study organisation exists training services, ongoing support and marketing support when replicating their business.

- To investigate the adaptation process of the operational model of the case study organization to the local environment based on the comparison of three franchisees in three different geographical areas.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Case Study Organization

“To provide employment opportunities of individuals of all kind of abilities and from all backgrounds through the sale of high quality refurbished ICT equipment.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

“Within five years, social franchise hopes to become Europe’s largest electronic and electrical equipment asset recovery organisation and provider of IT and electrical equipment for social enterprises.”(case study organization, online press release).

4.1.1. Collection of ICT Equipment

“For us it is crucial to get the right material in the door. It is very important that we get high quality equipment, which we are able to offer to our demanding customers.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

4.1.2. Processing ICT Equipment

“Reuse as an activity must be regulated as it needs to take a place in a sustainable fashion. It is essential that “sham-reuse” is eradicated. This can only be done by setting standards, which refurbishers must achieve before they can gain access with equipment with potential for reuse. We have implemented standard PAS 141, which enables us to reach the highest quality and get confidence into our products.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

“We are currently undertaking the following activities in preparation for the reuse process: visual inspection, safety test, function test, data eradication, software removal/uploading, disassembly, repair and testing and cleaning.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

4.1.3. Distribution, Demand and Market for Refurbished ICT Equipment

- Academic & Educational—schools & colleges, training centres;

- Charities & non-profit organizations;

- Local authorities and others with Green Public Procurement mandates;

- Students—individual end-user students across all levels (first, second, third & part time students);

- Eligible Recipients—as per Microsoft licensing specifications, eligible recipients include people who are disadvantaged in some way (disability, unemployed, living in a disadvantaged area etc.);

- Trade—local trade & international brokerage markets;

- Business Users—SMMEs, start-up companies; and

- E-commerce—developing innovative and engaging websites and apps selling directly to end users.

“Our market is very demanding and includes potential franchisees and all customers who want to buy high quality low cost refurbished equipment and save money.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

“This step was very important for the development and growth of our company, as this is how we identify which member has the managerial experiences and resources to adopt the company’s operating model. We certainly don’t want to waste our time and others time, if the partner is not appropriate.”(case study organization, interview with the director).

4.2. Overview of Case Study Organization’S Franchisees

4.2.1. Irish Franchisee

“To provide high quality refurbished ICT equipment and create real jobs for people with disabilities and therefore flourish and maximize the economic, social and environmental impact.”(Irish franchisee, interview with the director).

“Our primary delivered services are collection of ICT equipment and WEEE with potential for reuse, refurbishment of ICT equipment under PAS 141 standard and resale of these equipment to our markets. We believe quality of the reused products is crucial to create demand.”(Irish franchisee, interview with the director).

“To date, more than 90,000 ICT equipment has been reused, resold and donated. Support of local employment services help us a lot to follow our mission. With Tús programme, we have integrated more than 80 people with disabilities, who have found meaningful jobs through training services that we provide. Based on a tested and efficient business model along with a well-known brand that was adopted from the franchisor, our franchisee has succeeded in providing an economic, environmental and social impact and fully adopt the operational model.”(Irish franchisee, interview with the director).

4.2.2. U.S. Franchisee

“We serve any individual who has experienced a life-changing incident requiring them to learn a new occupational skill, any individual experiencing behavioural health issues and any wounded warrior. We also offer housing opportunities for individuals who require supported living and who are diagnosed with a serious mental illness.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

- (1)

- Create employment in ICT refurbishment & retail of ICT;

- (2)

- Provide training opportunities

- (3)

- Offer low-cost equipment available to marginalized groups & individuals;

- (4)

- Reduce waste and promote the reuse of ICT; and

- (5)

- Make financial contributions and ensure sustainability.

“When looking to adapt a business model to suit a U.S. culture, it was important to consider the impact on our cultural and local market demands. It was important to consider also that, geographical distance and different time zones. Sometimes it was difficult to communicate, like to get instant online assistance.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

“I am running this organization for the last 25 years and I had a desire to expand business in the recycling of the ICT equipment. I believe that the capability of adaptation of the process by required standards and promotion are key elements to the success of our franchisee. Our brand is a well-known in the state of Arizona and we weren’t sure, if we go ahead with new brand, as it might confuse our customers. So we decided not to adopt the franchisor brand.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

“Adaptation of asset recovery software system was challenging, as customary units had to be localized (for example, the currency EUR had to be changed into the US dollar, kilograms to pounds, kilometres to miles etc.), which incurred additional costs.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

“We sell our products to local charities, schools and end users. We are working closely with franchisor, he is providing us with some marketing material, which we use and adopt into our local market. We are present at our local NGO days, open days for schools, shows to promote our business. At the moment we working hard to promote our website and looking the opportunities in our neighbour country Mexico.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

“We are currently looking to apply for the fund for social enterprises in the frame of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. At the moment we are receiving governmental and federal support for people with disabilities.”(U.S. franchisee, interview with the CEO).

4.2.3. Slovenian Franchisee

“To provide low cost high quality refurbished ICT equipment and create real jobs for people with disabilities”(Slovenian franchisee, online resource).

“I think that the key to successful establishment of franchisee was capability to transfer and adopt Irish model, which is more commercially driven. I am glad that we found that kind of social franchise, as in Slovenia is missing key entrepreneurial competences and business drive in social enterprises. I also believe that my previous leadership competences, gained from experiences in both—pure commercial industry and in not for profit organization—contribute to the successful growth of the company. If you want to run a social enterprise, you have to have commercial experiences and you have to be able to attract the right people to get necessary resources. So at the start, we got support from a local mayor, who provided us with necessary space for the operation of the business.”(Slovenian franchisee, interview with the director).

“In the first phase is crucial for us to establish the market. So we are putting all efforts on the demand side of the business. Supply, which is of course also very important aspect of our business, is currently gained mainly from the franchisor in Ireland, brokers and some local companies in Slovenia. In the second phase we are planning to develop asset recovery business here locally.”(Slovenian franchisee, interview with the director).

“Of course there was a bit challenge, when adopting Irish model in Slovenia. First, the mind-set and cultural differences between both countries are affecting day-to-day activities, especially regarding marketing. I have witnessed that customers here in Slovenia are precise and more demanding when it comes to the refurbishment equipment, as customers in Ireland or in U.S. Therefore, we need a lot more efforts and promotion to establish a confidence in the customers. I think that is because second-hand products in general have bad reputation in Slovenia.”(Slovenian franchisee, interview with the director).

“The support is in a way provided by the government, but it still shows the lack of understanding of the role of social entrepreneurship. Mechanisms and support are not always well distributed and properly defined. For example, in Ireland and in the U.S., the educational sector is the biggest customer of refurbished ICT. That is not the case in the field of reuse of ICT in Slovenia, in spite of the provided institutional framework in Slovenia and the associated support mechanisms. Instead of supporting green procurement for social enterprises and encouraging schools to buy refurbished ICT, the government puts forward barriers such as financing schools with money only to be used to buy new equipment.”(Slovenian franchisee, interview with the director).

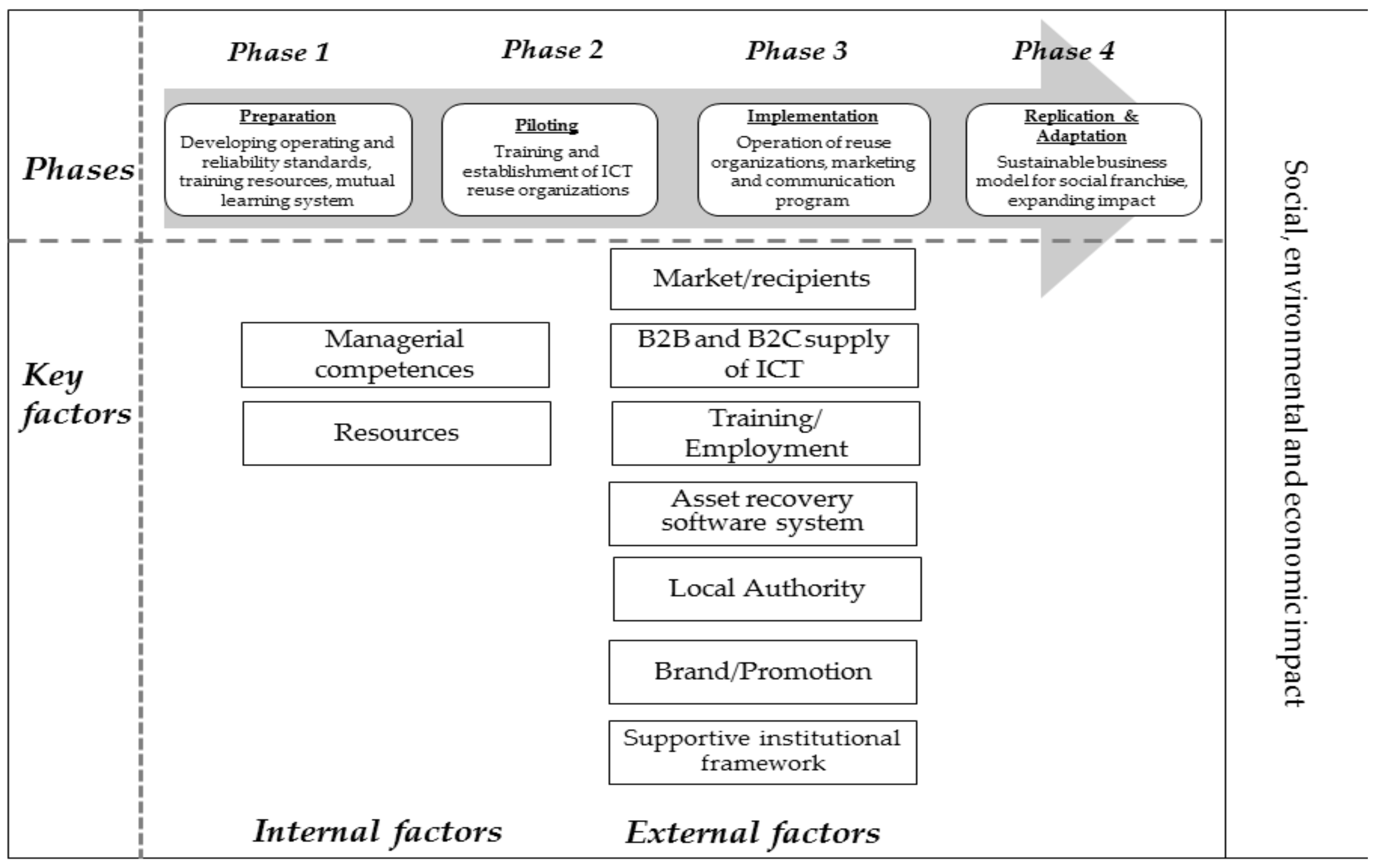

4.3. Development of Social Franchising Model

- Training services in order to help professionalize the franchisee which is working or wish to work in the reuse industry;

- Professional services to the franchisee to achieve a sufficient supply of equipment for its sustainability;

- Technical support to reuse organisation in setting up and operation and operations manuals;

- Use of asset recovery software system and PAS 141 standard;

- Use of brand and promotion;

- Sales and marketing support to the franchisee; and

- Ongoing support and quality assurance to continue to develop the asset recovery processes for the reuse of ICT equipment and increase in reuse and reduction of WEEE.

- Competing with firms that feign a social mission or confuse the social service marketplace solely for the purpose of enhancing owner and/or shareholder value;

- Navigating complex resource allocation decision environments where multiple stakeholders must be satisfied;

- Maintaining continuous innovation in both business practice and social mission environments;

- Attracting and retaining management talent while competing in a for-profit compensation environment;

- Developing meaningful measurement and reporting processes that accurately model social value creation for the short-, medium- and long-term;

- Finding the right partner who has met all the criteria that the case study organization developed; and

- Adapting the model to its cultural and environmental specifics.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What is your business experience? How many years of experience do you have in this industry? In this business?

- Where did you get resources to set up this business? (e.g., governmental support, bank loan, own capital, …)

- Can you describe your mission?

- How do you make your money?

- Could you outline and describe your operational model and its key factors for success?

- Is there any custom-designed software that you use?

- On what basis do you choose your franchisees?

- What are the most important attributes of a successful franchisee?

- What initial services do you offer to your franchisees?

- Do you provide on-going training in the form of courses, workshops, conferences, seminars, regional meetings?

- What kinds of marketing programme do you run for the product or service offered by the franchisees?

- How well is franchisee likely to fit with your organization in terms of personal standards, aspirations and values?

- Was adaptation process difficult?

- Has each franchisee adopted your brand?

- What phases were necessary to scale up your operational model?

- What were the challenges? Geographical spread, different culture, …?

Appendix B

- What is your business experience? How many years of experience do you have in this industry? In this business?

- Where did you get resources to set up this business? (e.g., governmental support, bank loan, own capital …)

- Can you describe your mission?

- How do you make your money?

- Could you outline and describe your operational model and its key factors for success?

- How well is your organization likely to fit with franchise in terms of personal standards, aspirations and values?

- Was adaptation process difficult?

- Did you adopt franchisor band?

- What phases were necessary to scale up your operational model?

- What were the challenges? Geographical spread, different culture, …?

- What dollar value is spent on marketing? How is marketing funded? How accountable is the franchisor for the funds? Am I required to spend additionally on promotions in my local area? How much? Is supplier support available?

- Do you have a launch package for a new franchised territory? What experience is this based on? What does it include? Who pays?

- What help will I receive in arranging local advertising and promotions? Are there standard promotions (e.g., radio adverts) available for my use?

- How does the franchise use social media? Are there standard pages or can I manage my own? What assistance/policies are in place to control the use of social media by franchisees?

- Please show me examples of marketing material you provide, e.g., point of sale material and promotional literature such as brochures, leaflets, sales presenters, digital advertisements, Adwords promotions.

- Is there a website promoting the franchise? Is it optimized for mobile phones? Is it GPS-enabled? Can customers buy direct from the website? If so, are franchisees recompensed for sales in their area? Online sales can be a source of friction if not properly managed—read more.

- Does the franchise carry out database-related promotions to customers? How is the database created and managed? Can franchisees choose which offers are made to which customers?

- Is there a website promoting the franchise? Is it optimized for mobile phones? Is it GPS-enabled? Can customers buy direct from the website? If so, are franchisees recompensed for sales in their area? Online sales can be a source of friction if not properly managed—read more.

References

- Rey-Martí, A.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Palacios-Marqués, D. A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. Stakeholder Theory and Organisational Ethics; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1576752685. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, C.; Schmidheiny, S.; Watts, P. Walking the Talk: The Business Case for Sustainable Development; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1576752340. [Google Scholar]

- Crucke, S.; Decramer, A. The Development of a Measurement Instrument for the Organizational Performance of Social Enterprises. Sustainability 2016, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahra, S.A.; Rawhouser, H.N.; Bhawe, N.; Neubaum, D.O.; Hayton, J.C. Globalization of Social Entrepreneurship Opportunities. Strat. Entrep. J. 2008, 2, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G.; Anderson, B.B.; Wei-Skillern, J. Scaling Social Impact: Strategies for spreading social innovations. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2004, 1, 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, D.; Hedley, S.; Nicholls, J. Growing Pains: Getting Past the Complexities of Scaling Social Impact. 2014. Available online: http://www.thinknpc.org/publications/growing-pains/ (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- ATKearney. Scaling Up: Catalyzing the Social Enterprise. 2015. Available online: https://www.atkearney.com/documents/10192/5487100/Scaling+Up%E2%80%B9Catalyzing+the+Social+Enterprise.pdf/1f1a024a-a7a5-4763-8739-50887139df47 (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei-Skillern, J. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westley, F.; Antadze, N.; Riddell, D.J.; Robinson, K.; Geobey, S. Five Configurations for Scaling Up Social Innovation: Case Examples of Nonprofit Organizations from Canada. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2014, 50, 234–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, B. Exploring the Contingencies of Scaling Social Impact: A Replication and Extension of the SCALERS Model. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 28, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, P.; Jarvis, O. Toward a Theory of Social Venture Franchising. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartilsson, S. Social Franchising—Obtaining Higher Returns from Investments for Jobs in Social Enterprises; Coompanion Göteborgsregionen: Göteborg, Sweden, 2012; Available online: http://www.ekonomiaspoleczna.pl/files/ekonomiaspoleczna.pl/public/_MRR_Better_Future/Report_Social_Franchising_120524.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- O’Connell, M.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Hickey, S. Investigating reuse of B2C WEEE in Ireland. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology (ISSST), Arlington, VA, USA, 17–19 May 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Streicher-Porte, M.; Marthaler, C.; Böni, H.; Schluep, M.; Camacho, A.; Hilty, L.M. One laptop per child, local refurbishment or overseas donations? Sustainability assessment of computer supply scenarios for schools in Colombia. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3498–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahhat, R.; Williams, E. Product or waste? Importation and end-of-life processing of computers in Peru. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6010–6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissling, R. Best Practices in Re-Use. Success Factors and Barriers for Re-Use Operating Models; Project Report; Solving the E-Waste Problem; Empa: St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, F.; Fernandez, H. Third Sector Research Centre Working Paper 79; Third Sector Research Centre: Birmingham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Kröger, A.; Lambrich, K. Scaling social enterprises—A theoretically grounded framework. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 2012, Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Annual Entrepreneurship Research Conference, TCU Campus in Fort Worth, TX, USA, 6–9 June 2012; Arthur M. Blank Center for Entrepreneurship: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 752–766. [Google Scholar]

- Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, T.M.; Matear, M. Social Entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, T.; Vaccaro, A. Stakeholders matter: How social enterprises address mission drift. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 143, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Kröger, A.; Demirtas, C. Scaling Social Impact in Europe—Quantitative Analysis of National and Transnational Scaling Strategies of 358 Social Enterprises, 2015. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu.ludwig.lub.lu.se/74119/1/Scaling_social_impact.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Bradach, J.L. Going to Scale: The Challenge of Replicating Social Programs. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2003, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.; Szulanski, G. Replication as Strategy. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Krogh, G.; Cusumano, M.A. Three Strategies for Managing Fast Growth. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2001, 42, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy, B.S. Adaptation: A promising metaphor for strategic management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josiah, J.S. Approaches to Expand NGO Natural Resource Conservation Program Outreach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.N.; Chatterji, A.K. Scaling social entrepreneurial impact. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 51, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A.J. Franchising & Licensing: Two Powerful Ways to Grow Your Business in Any Economy, 3rd ed.; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0814472224. [Google Scholar]

- Sharir, M.; Lerner, M. Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 2005, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, H.M.; Crutchfield, L.R. Creating High-Impact Nonprofits. Available online: http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/735/ (accessed on 8 August 2018).

- Bloom, P.N.; Smith, B.R. Identifying the Drivers of Social Entrepreneurial Impact: Theoretical Development and an Exploratory Empirical Test of SCALERS. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinelli, M.; Maiolini, R. Strategies for Sustainable Development: Organizational Motivations, Stakeholders’ Expectations and Sustainability Agendas. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Bridgespan Group. Growth of Youth-Serving Organizations, 2005. Available online: https://www.bridgespan.org/insights/library/children-youth-and-families/growth-of-youth-serving-organizations/appendices (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Kickul, J.; Lyons, T.S. Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: The Relentless Pursuit of Mission in an Ever Changing World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0415884891. [Google Scholar]

- Wei-Skillern, J.C.; Austin, J.E.; Leonard, H.; Stevenson, H. Entrepreneurship in the Social Sector; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1412951371. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, M.; Castrogiovanni, G. Franchising: A Review and Avenues to Greater Theoretical Diversity. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Richardson, K.; Turnbull, G. Expanding Values; A Guide to Social Franchising in the Social Enterprise Sector; SESF Development Partnership, VATES Foundation: Helsinki, Finland, 2007; ISBN 978-952-5716-02-3. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, J.; Stanworth, J. Franchising in the modern economy: Towards a theoretical understanding. Int. Small Bus. J. 1983, 2, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziólkowska, M. Success Factors and Benefits of Social Franchising as a Form of Entrepreneurship. Stud. I Mater. 2017, 23, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.; Kuehr, R. Today’s markets for used PCs and ways to enhance them. In Computers and the Environment: Understanding and Managing Their Impacts; Kuehr, R., Williams, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 978-1-4020-1679-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgin, M.; Gupta, S. Environmentally conscious manufacturing and product recovery (ECMPRO): A review of state of the art. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissling, R.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Boenia, H.; Luepschenc, C.; Andrewd, S.; Dickensone, J. Definition of generic re-use operating models for electrical and electronic equipment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 65, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, D.; Roux, D. Second-hand Shoppers’ Motivation Scale: Antecedents, Consequences, and Implications for Retailers. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.; Fitzpatrick, C. RE-Evaluate Reuse of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (Evaluation and Mainstreaming), EPA STRIVE Programme 2007–2013; Environmental Protection Agency: Wexford, Ireland, 2013; ISBN 978-1-84095-504-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, J.; Botezatu, I.; Herreras, L.; Liddane, M.; Hintsa, J.; Luda di Cortemiglia, V.; Leroy, P.; Vermeersch, E.; Mohanty, S.; van den Brink, S.; et al. Countering WEEE Illegal Trade (CWIT) Summary Report, Market Assessment, Legal Analysis, Crime Analysis and Recommendations Roadmap; Countering WEEE Illegal Trade (CWIT) Consortium: Lyon, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, R.H.; Lo, H.C.; Yu, R.Y. A study of maintenance policies for second-hand products. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2010, 60, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, L.; Vrancken, K.; Manshoven, S. Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centres of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability 2016, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 312, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers; Blackwell: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | SCALERS Model Success Drivers/Factors | Scalability Framework Key Components | Social Franchising Success Factors | Success Factors of ICT Reuse Operating Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success factors |

|

|

|

|

| Research Sub-Objectives | Key Interview Questions |

|---|---|

| Research sub-objective 1.1: To investigate business experience and resources needed for the establishment of the franchise. |

|

| Research sub-objective 1.2: To investigate, what the key success factors of the operational model of the franchise are. |

|

| Research sub objective 1.3: To investigate the key characteristics for a successful member. |

|

| Research sub-objective 1.4: To investigate, whether in the case study organisation there exists training services, ongoing support and marketing support when replicating their business |

|

| Research sub-objective 1.5: To investigate the adaptation process of the operational model to the local environment based on the comparison of three franchisees in three different geographical areas |

|

| Section | Essential Elements | Desirable Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership & Experience |

|

|

| Organizational Services |

| |

| Values & Interests |

| |

| Financial Situation |

|

|

| Premises |

|

|

| Partnerships |

|

|

| Technology |

| |

| Legal |

|

| Element of Comparison | Case study Organization–Social Franchise in the ICT Reuse | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Irish Franchisee | U.S. Franchisee | Slovenian Franchisee | |

| Managerial competences | CEO has managerial experiences and competences in the ICT reuse industry. | CEO has managerial experiences and competences in charity | Director has managerial experiences and competences in commercial company |

| Resources for the establishment | Franchisee got support for establishment from individuals, who run franchisee and from local authority. | Franchisee got support from its sister enterprise and from government. | Franchisee got government support for start-up social enterprise, support from Irish franchisor and support from local authority. |

| Market/Recipient |

|

|

|

| Geographical focus | Ireland, UK | Arizona, Mexico | Slovenia, Italy, Croatia, Austria |

| Supply (source) |

|

|

|

| Creation of economic, social and environmental impact |

|

|

|

| Process and system |

|

|

|

| Local Authority support | Local authority support was one of key factors for the establishment of franchisee. | Local authority support was one of key factors for the establishment of franchisee. | Local authority support was one of key factors for the establishment of franchisee. |

| Brand/Promotion | Brand was adopted. | Brand was not adopted. | Brand was adopted. |

| Supportive institutional framework | TÚS programme for providing short-term working opportunities for unemployed people. | Community development programmes sponsored by government and federal contracts. | Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, local government initiatives, which support development of social enterprises. |

| Legal form | Limited Company by Guarantee. | Charity 501(c) | Limited company, registered as social enterprise |

| Adaptation of the model | Entire adoption of the model without distinction. | Adoption of the model with certain adjustments. | Adoption of the model with certain adjustments. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zajko, K.; Bradač Hojnik, B. Social Franchising Model as a Scaling Strategy for ICT Reuse: A Case Study of an International Franchise. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093144

Zajko K, Bradač Hojnik B. Social Franchising Model as a Scaling Strategy for ICT Reuse: A Case Study of an International Franchise. Sustainability. 2018; 10(9):3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093144

Chicago/Turabian StyleZajko, Katja, and Barbara Bradač Hojnik. 2018. "Social Franchising Model as a Scaling Strategy for ICT Reuse: A Case Study of an International Franchise" Sustainability 10, no. 9: 3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093144