1. Introduction

Brand is a key element of competitive advantage for service providers [

1]. The brand name of a company and its visual presentation combined with promotional strategies and symbolic associations are the main elements of the brand [

1]. Awareness of the company’s name is the first step toward consumer-based brand equity building and consumers’ choice [

2]. The consumers first get to know the company’s name, then the name forms the consumers’ view on the image and the purpose of the company and its activities [

1]. If someone knows the brand of the company and correctly assigns the company name to a certain category of services, he will probably become a customer of a company as well [

3]. When consumers choose and evaluate products, brand awareness plays a critical role. Companies employ a “brand strategy” as their main focus to strengthen their positions in the market and to establish consumer loyalty to the brand.

For new and small businesses, brand awareness is crucial [

4]. Well-known brands obtain consumer confidence, which allows consumers to take advantage of the known services of the company [

5]. One of the strengths of a well-known brand is that it reduces the risk to consumers using an intangible product. Another advantage, from the perspective of a long-term business, is the fact that it creates a stable demand for service from the consumer side, which helps to increase the market share of the employment services. These benefits add value to the company’s profitability, which may be the main goal of creating a brand awareness service [

1].

Awareness is the first step toward the formation of brand equity. Awareness is the ability of consumers to recognize and to recall the particular product or service and to assign it to a particular category of products and services [

6]. Brand recognition allows consumers looking for clearer clues to recognize the brand, and brand recall indicates that consumers are capable of recalling certain brands when provided with particular product or service categories, i.e., to recall a specific brand from their memories [

7]. Companies seek the recognition of their brand, and this requires two elements: increasing the brand identity and linking features that relate to the brand with the company’s services [

8].

Brand awareness and trust are particularly relevant for the employment agency sector. While employment and sustainability are rarely related in research literature, labor-related factors are key drivers of a sustainable economy. Many recent technological developments and societal challenges provide opportunities for the redefining of work conditions and for access to more fair and equal work conditions [

9]. Addressing the problem of unemployment is one of the main challenges of long-term sustainable development, especially considering youth unemployment [

10] and the large amount of emigration in the Central European region.

Social sustainability includes several aspects, such as worker empowerment, economic growth, the reduction of poverty, and access to work [

11]. Closely linked is the idea of corporate social sustainability (CSR) [

12], which applies the aspects of social sustainability at a company level, therefore contributing to increased social sustainability at national and regional levels. On the other hand, companies see sustainability as a factor that allows for increased brand awareness and as having the potential to strengthen the status and image of a company both for consumers and against it competitors. Managing socially responsible relationships with consumers leads to the development of sustainability networks and to the creation of strong brands [

13]. In aiming for sustainable development, employment agencies can be seen as first-order agents, which have direct influence and responsibility when implementing the goals of social sustainability. For example, they work to increase the awareness of people looking for a job, provide necessary skills for sustainable economics, and create partnerships between employment sector actors [

14]. In fact, this increased awareness is seen as a fundamental component of sustainable development [

15]. Furthermore, trust is an important mediating variable when considering consumer attitudes toward a corporation and its corporate reputation [

16]. A sincere and trustworthy relationship between consumers and brands leads to an interactive relationship influencing consumer choices [

17]. Trust as a factor also correlates well with success and transparency [

18], key factors of sustainability. The employee’s trust in an organization as their place of work may depend on safe working conditions. This may be revealed by the extent to which employees will want to remain in their current position in the labor market and in the future.

Therefore, the role of employment agencies as providers of a socially important service and in supporting sustainable employment is growing. Employment agencies are defined as intermediaries between employees and employers, who help employers find the right candidate for a job position and help employees to find an appropriate position. However, high competitiveness in the employment market (currently there are 250 public and private employment companies in Lithuania [

19]) makes it more difficult to distinguish brands of employment agencies, especially when there is little investment in brand awareness. Furthermore, the employment industry sector is sometimes associated with unethical and dishonest behavior in the eyes of the consumers, which makes it difficult for new brand names to earn good reputations and trust from their customers.

There are several reasons for the alleged bad reputation of employment agencies in the region. Firstly, employment agencies are seen as a front-end of the employers aiming to offset work conditions and to reduce hourly payment rates, especially when low-skill workers are hired [

20]. Furthermore, there is social stigma associated with the customers of the employment agencies as people who cannot find jobs by themselves. In some cases, this is supported by econometric evidence claiming that unemployed job seekers who use the services of a public employment agency have longer unemployment spells than others using alternative pathways to find work [

21]. Also, recruitment agencies have been seen as having bias against minority and disadvantaged groups such as elderly people [

22]. Understanding such factors is important when aiming to gain a competitive edge in the employment market and in contributing towards sustainable employment practices.

Here, we analyze the factors affecting brand awareness (one of the dimensions of brand equity) in the employment agency business sector and present an employment agency in Lithuania as a case study. We use this case study to show the importance of increasing social sustainability through brand awareness in the context of consumer mistrust, which is strong in this sector.

2. Brand Awareness and Trust in the Service Industry

In the service industry, the company name is a brand of its service [

23]. The company brand helps consumers to create and share a common image of the company, which includes such factors as reliability, trustworthiness, reputation, quality, experience, consumer feedback and recommendations. Recently, more attention has been given to the brand service [

23] and its consumer perception. Trust in consumer brand can serve as a mediator between consumer perception and brand reputation [

16].

The brand is applied and valued differently in the service industry because of different service characteristics [

24]. Four characteristics distinguish the product from the service [

25]. The first characteristic is intangibility, which means that the service cannot be touched, tasted, or seen, contrary to the product. The second characteristic is inseparability, which means that the presentation and use of the service are carried out at the same time, opposite to those of the product. The third characteristic is heterogeneity, when the service is provided differently to each consumer, e.g., in the field of employment, each customer receives different employment service and conditions. The last characteristic is defined as maturity, i.e., the service, unlike the product, cannot be stored for later use, as it causes a supply and demand problem that can be very difficult to synchronize with a company. A service mark is more important than a product’s brand, as consumers have no tangible attributes when evaluating and comparing a service with a product [

25].

Prominent models, such as Brand Synthesis and Brand Awareness Model for brand awareness in the service sector [

1], are aimed at exploring brand awareness through the product [

5]. The most widely used is the brand model for the product [

6]. Berry has adapted and upgraded a model that is tailor-made for the service sector and can measure company brand awareness through branded elements introduced by the company and by external service brand communication [

1], which includes word of mouth and other external marketing activities.

The Brand Awareness Model in services emphasizes two factors: a company-provided service mark and external service brand communication [

26]. Compared to the Brand Awareness Model in the product category [

5], it has introduced two elements: product brand replication and recognition. However, different models are constructed for a product [

6] and for a service [

1]. The dimensions are similar because the prevailing factors that measure brand awareness through brand recognition and replication are created through the way a company presents its brand to consumers and how well consumers are able to remember the brand. The branding dimension introduced by the company is examined through the name of the company and the elements of advertising. The name of the company can reduce the risk for consumers when acquiring the service, as the first things they notice are external factors such as the company name and logotype [

1]. When analyzing this factor, the respondents must spontaneously identify the brand category [

27]. An effective company brand directly contributes to the company’s reputation. It is important for the company to have some kind of association with the company services, such as being simple, distinctive, and easily recognizable [

6]. After creating the awareness of the brand, the second step toward brand equity creation is the creation of associations in the minds of the consumers [

28].

Advertising is a powerful weapon supported by marketing research that helps to determine which ads are effective for existing and potential clients of the company. As the behavior of the consumers changes on the basis of what is socially acceptable and evolving in their environment, it is important for the brand to adapt to this environment and advertise in the location and time where the company can reach its potential customers most effectively [

6].

Consumer perception needs to be positive and coherent [

24]. This is important because the same message should be disseminated through different communication channels in order to make a positive impact [

29,

30,

31]. Advertising can be used to improve brand awareness, in relation to the service and service category [

32]. More extensive investment in advertising leads to an increasing awareness of that company [

33]. Responsiveness is a very powerful factor that influences consumer behavior [

34], and more popular brands are more likely to enjoy positive feedback from consumers than nameless ones with little popularity [

35,

36].

External brand communication (such as by fans of the brand) helps consumers to gather information about the company and its services [

1]. Recommendations and company publicity, e.g., disseminated as articles in the media, are the most common forms of external branding. Consumers can start trusting the company as a result of the impression they have about the company not only from communications provided by the company, but also from the opinions of independent people [

31]. Recommendations are the general assessment of consumers of the characteristics of the services [

1]. Recommendations are more relevant in the context of services than goods [

37]. It is more difficult to assess a product than a service, as it requires to obtain physical ownership of a product, therefore the consumer is more likely to rely on the experience of other consumers [

1,

37]. The consumers who use the service are considered as a more objective source of information [

38].

Popular brand names help consumers to mitigate their cognitive risks and to form positive appraisals [

39]. Brand awareness shows stronger links between brands and consumers’ memories [

40]. Such findings reflect consumer capability in discerning differences between brands, which indicates stronger connections or traces in consumer memories. Brand awareness is regarded as an approach for measuring the strength of the impression made in consumers’ minds [

41].

Brand awareness has an impact on consumer decisions, suggesting that brand awareness is often under consideration in decision-making [

42]. Brand awareness may influence consumers’ perceptions, attitudes, or even affect their decisions and brand loyalty [

43], e.g., consumers hold positive attitudes towards unfamiliar products with high brand awareness. On the contrary, in the case of products with low brand awareness, extra information on this product type is required for assessment, because consumers are unfamiliar with the brand names.

The employment service sector is regarded rather negatively by consumers, because of a lack of trust and good reputation [

31]. The employment sector has negative associations in the Lithuanian market, therefore publicity could increase consumer confidence in the sector and its services. Corporate visibility means controlling information to reach one or more audiences with the aim of influencing their decisions and opinions about the company or the company's brand [

38]. Publicity in the media is often associated with positive attention, but media attention that would negatively influence consumer opinion is also common and cannot be controlled by the company [

38,

44]. It can however have a high impact on the attitudes towards the brand and on the service industry as a whole.

4. Results

After assessing the credibility of the independent variables in the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.721 for the brand of the company and 0.774 for external brand communication. These indicators are shown in

Table 2 for reliability between variables. Note that Cronbach’s alpha was evaluated using the following rules of thumb: 0.9—excellent reliability, 0.8—good, 0.7—acceptable, 0.6—controversial, 0.5—poor, and <0.5—unacceptable reliability [

48]. The survey can be considered as statistically reliable, since Cronbach’s alpha was >0.7.

Descriptive statistics indicated how many respondents answered the questions (N), which was the highest and lowest rating on the Likert scale for brand dimensions. The average and the standard deviations were also calculated. The brand awareness of X brand was examined through the brand provided by the company, i.e., the name of the company and its advertising, as well as by external brand communication, i.e., recommendations and brand awareness. These dimensions were considered important to understand the extent to which potential users were important. The branding dimension of the company was not missed, as all respondents answered all the questions asked. Questions of this dimension were presented on the Likert scale, with the lowest value given by the respondents as 1, and the maximum value as 5, from the 5-item scale. In estimating the importance of the brand introduced to consumers, the average was 3.594, and the standard deviation was 1.056. When analyzing the external dimension of the brand communication, the respondents answered 111 questions, the lowest value was 1, the maximum was 5. The average value was 4.261, and the standard deviation was 0.805 (see

Table 3).

The normality test found that the correlation between variables was non-parametric, so the Spearman correlation was used, because it can be used for abnormal distributions. The values of the Spearman correlations are shown in

Table 4 (all values are significant). To evaluate them, we used the following rules of thumb for the Spearman correlation: 0.90 to 1.00—very high, 0.70 to 0.90—high, 0.50 to 0.70—moderate, 0.30 to 0.50—low, 0.00 to 0.30—little if any [

49]. Therefore, we evaluated all correlations as moderate.

Regression analysis showed that all independent variables had a positive relationship with the company’s reputation (see

Table 5). External brand communication had the most significant impact on the company’s reputation (

B = 0.398,

p = 0.000), which indicated that if the external brand communication increased by 0.398, then the awareness of the company would increase by one positive point. The brand provided by the company also had a rather significant impact on the company’s reputation (

B = 0.279,

p = 0.005), and if we increased the company’s reputation by 0.279, the company’s awareness would increase in one positive point.

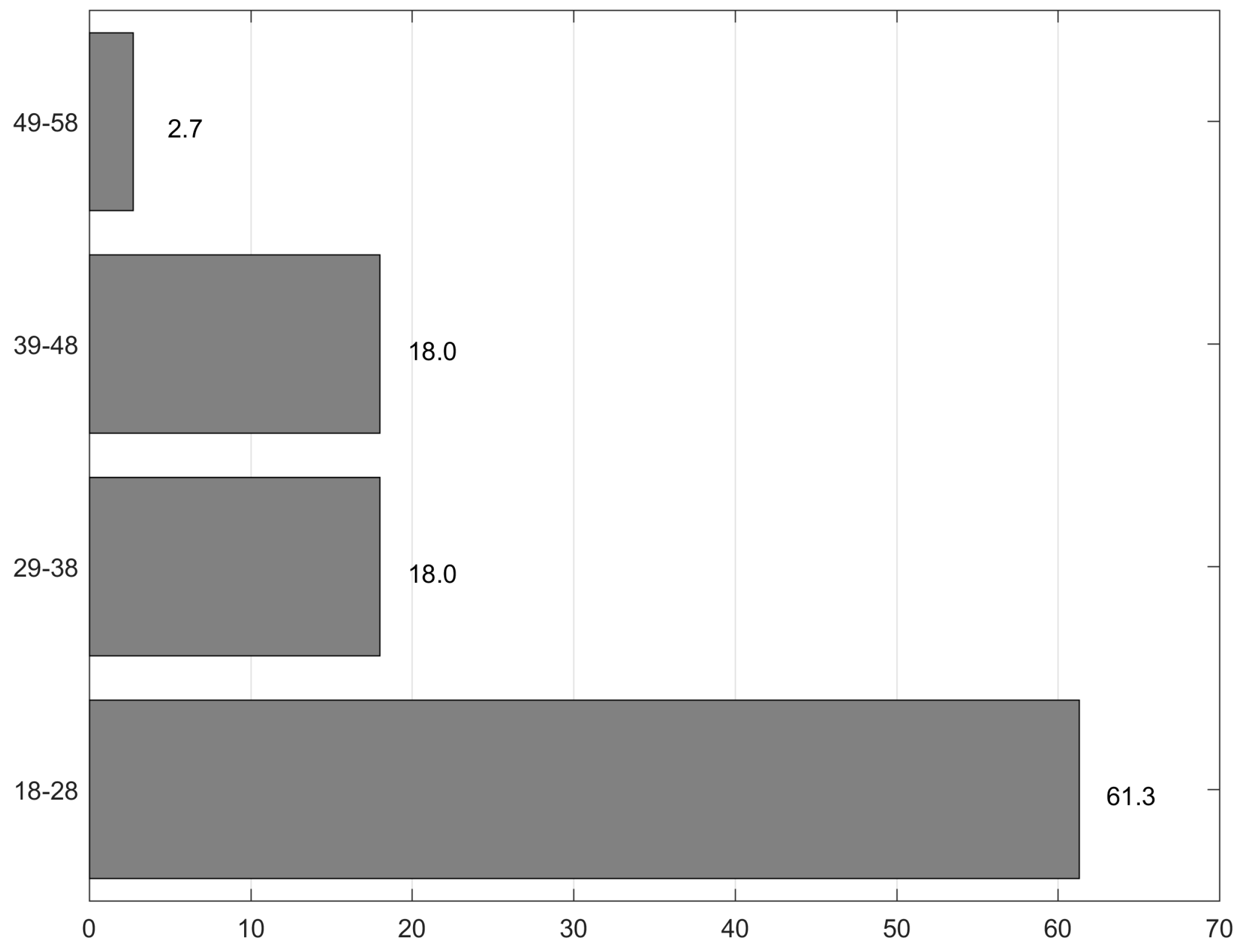

Demographic issues. The survey included 56.8% (

N = 63) men and 43.2% (

N = 48) women. The distribution of the respondents was not the same for age groups (see

Figure 1). Most respondents were in the age group from 18 to 28 years, 61.3% (

N = 68), 18% of the respondents were in the 29–38 and 39–48 years age groups (

N = 20), and 2.7% (

N = 3) were in the 49–58 years age group. A one-way ANOVA after a Bonferroni adjustment showed that there was a significant difference between age groups (

p = 0.000, F = 15.633) in brand awareness.

The distribution of respondents by place of residence was recorded using the following three options: metropolitan area (>100,000 inhabitants), city, and village (<7000 inhabitants). Most of the respondents had their place of residence in the metropolitan area: 61.2% (N = 68). A smaller proportion of the respondents came from a city, i.e., 37% (N = 41), and the lowest number of respondents resided in a village, i.e., 1.8% (N = 2) of all respondents.

The distribution of the respondents according to vocational classifications was as follows: skilled workers 68.5% (N = 76), unskilled workers 31.5% (N = 35) of all selected respondents.

The first question was introductory and asked, “How much trust do you have in recruiting agencies for recruiting abroad?” and aimed to identify the attitudes of the respondents and their confidence in recruiting agencies. After evaluating the answers of the respondents, 35% (N = 19) were “lightly confident” in employment agencies that employ foreign workers. Slightly fewer respondents chose “Very Trustworthy” for employment agencies, i.e., 22% (N = 24), and 17% and 9% of respondents indicated their mistrust in employment agencies that transfer people abroad (“I do not really believe” and “I do not trust”, respectively). Gender analysis showed that there were no significant differences between the genders on the issue of trust in the employment agencies (t-test results: t = −0.080, F = 2.793, p = 0.936).

The fifth question dealt with the most relevant criteria for potential clients when dealing with an employment service company, and the answers were evaluated on a 5-item scale (1—“not at all important”, 5—“very important”). While all criteria were quite important for potential users, the most important criteria distinguished the quality of the company services with a value of 4.76, with 81.1% of respondents choosing the most important criterion. Another important criterion for the consumers was to get customer feedback from a company by choosing an employment service (78%). The reputation of the company in the market was the most important for 73% of customers. The importance of a variety of job positions was the most important for 53% of consumers. However, all of the listed criteria were relevant to the respondents, since for all criteria the average value was higher than 4 points (see

Figure 2).

Considering the awareness of X brand among the potential customers, 26.8% of the respondents had heard of X, and 72.3% had not fully heard of this employment company. The gender analysis using the t-test showed no statistically significant differences between males and females (F = 0.756, t = −0.439 ± 0.02, p = 0.387).

With regard to the associations caused by the company brand name, 50% of respondents said X was associated with construction, 9.3% thought it was related with employment, and the rest 40.7% said that it was not associated with any business type.

The evaluation of the attractiveness of the consumer advertisement showed that the most noticeable ads was Internet advertising (4.40 ± 0.89), followed by outdoor advertising (3.50 ± 1.07), television (TV) advertising (3.43 ± 1.37), and radio advertising (2.89 ± 1.275) (see

Figure 3).

Gender analysis showed no statistically significant differences between males and females in the perception of Internet advertisements (F = 1.879,

t = −1.279

p = 0.173), outdoor ads (F = 0.799,

t = 0.318,

p = 0.373), and TV ads (F = 0.498,

t = −1.869,

p = 0.482). Also, there were no statistically significant differences between age groups in their views regarding Internet advertising (using

t-test; see

Table 6) as well as in views regarding outdoor advertising (Tamhane’s post-hoc:

p > 0.005, F = 0.792) and TV ads (Tamhane’s post-hoc

p > 0.005, F = 2.956). Summarizing, we can claim that customer views on Internet, outdoor, and TV advertising do not depend on the age or gender of the customers.

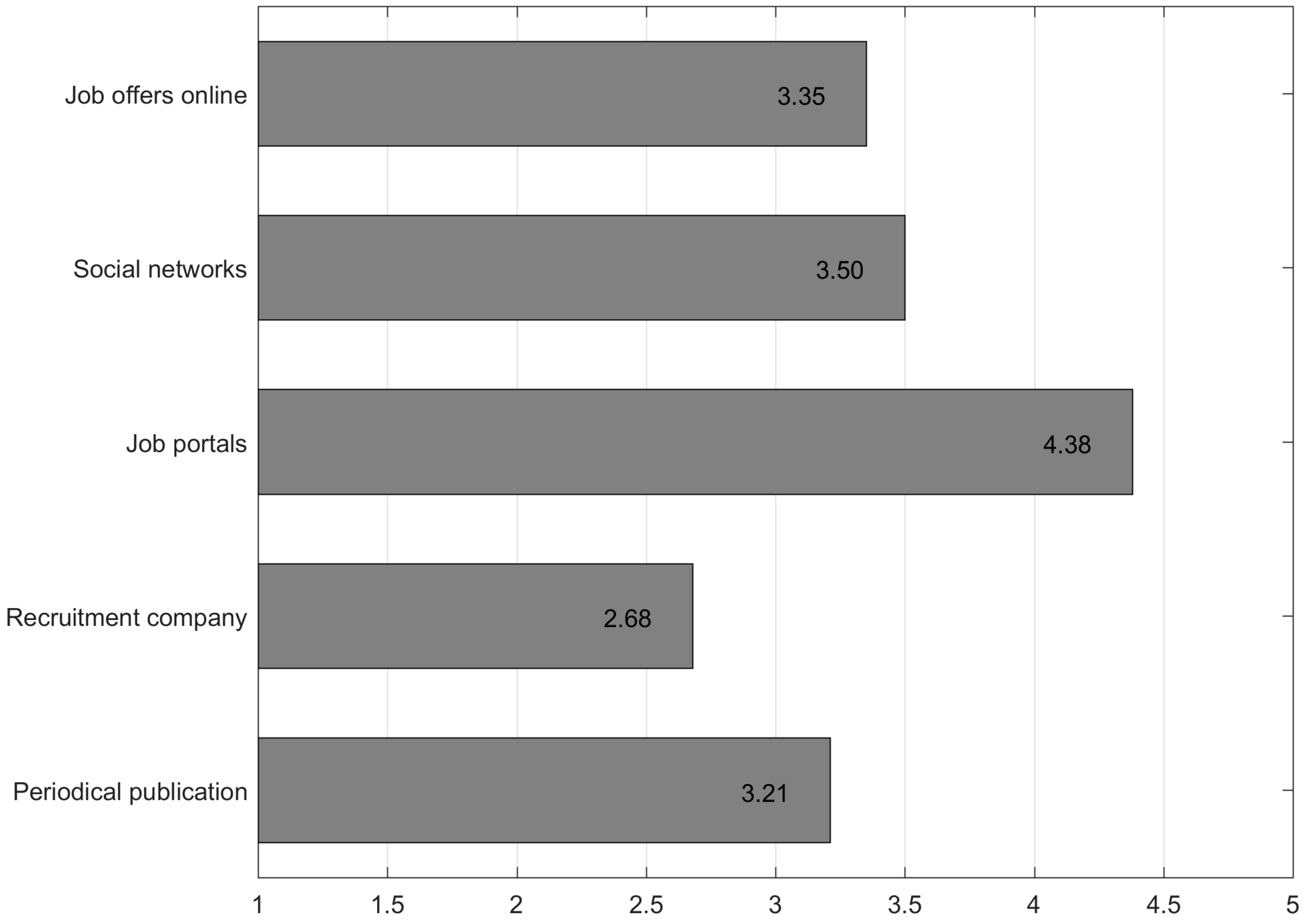

The respondents were also asked about where they would go to search for a job if they needed it. The 5-item Likert scale was used from “definitely not” to “definitely yes”. The respondents would definitely look for work through web portals for job advertisements (4.38 ± 1.08), social networks such as Facebook or LinkedIn (3.50 ± 1.46), online ads on dedicated web portals such as skelbiu.lt (3.35 ± 1.50), apply to the employment agency (3.21 ± 1.43), and look for work in newspaper ads (2.68 ± 1.48). See the results depicted graphically in

Figure 4.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Service companies create a strong brand through the brand’s characteristics and message consistency to match their services, reaching consumers emotionally and assimilating the service’s brand credibility [

1]. A well-remembered company name and its advertisements directly link the user to the category of service that penetrates the consumer’s emotional connection [

50]. The employment industry sector is often associated with unethical and dishonest behavior in the eyes of the consumers, therefore there is a need for research that would contribute not only to the “adjustment” of the brand association, but also to the formation of greater confidence by promoting the main value of the company (the provision of high-quality services to its customers). The need for corporate social responsibility increases the role of a company’s management in promoting sustainable leadership practices and increasing general sustainability awareness. That is, to be successful, companies must embed the principles of sustainability in the core of their strategy, services, and organizational culture. Trustworthiness, brand equity, and brand awareness are seen as some of the best mechanisms in achieving this aim [

51]. Consumer trust is the key determinant of corporate capital that determines the potential and success of any sustainable organization [

18] and creates valuable consumer–brand relationship. Building consumer trust can provide a competitive advantage for employment agencies [

52].

Social media provide significant benefits to service brand development [

53], as articles in social media aimed at the sharing of information through live chats, social networking, and online forums enhance a company’s reputation and trust amongst its potential customers.

The recommendations of a company’s existing customers are also important, because they allow the company to strengthen their brand in the market sector, which is not a fully developed market, especially in Lithuania, as the trust in employment enterprises is low because of the historically bad reputation of the sector [

54]. Therefore, directed marketing actions can resolve consumer distrust of employment companies by improving their image and market visibility [

55], thus contributing towards a vision of sustainable employment.

Our empirical study shows that the reputation of X employment company is most affected by the external brand communication, i.e., by word-of-mouth communication and publicity, which is an extension and/or consequence of brand communication. Increasing external brand communication would increase company awareness. Branding introduced by the company, i.e., the name and advertising, have slightly less influence, but they correlate with the company’s reputation. When selecting an employment company, one of the most important criteria is the reputation of the company, therefore, it is beneficial to increase levels of trust in the employment company to improve the company’s reputation. According to the respondents’ answers, the most important criterions for choosing an employment company are the quality of services (4.76) and customer feedback from the company (4.7).

We found that 35% percent of respondents were “lightly confident” in employment agencies that employ foreign workers and just 9% of respondents said “I do not trust” the employment agencies. Another important result of our quantitative study is related to gender research: we found no statistically significant differences between males and females in their perception of trust in employment agencies, brand awareness, and the perception of Internet, outdoor, and TV advertisements. Such results are in contradiction with some other works (such as [

56]), however the differences may be explained by other factors such as geographical region, cultural attitudes, and the topic of advertisement, which were not considered by the current study.

The limitations of the study are as follows. The size of the sample was smaller than recommended, which prevented the study from achieving more accurate results. As the X employment company targets specific customers (qualified and unskilled workers), it was difficult to reach the target audience using an Internet-based survey, therefore, there was a significant bias in the age of the respondents (more than half of the respondents (61.3%) was in the 18–28 age group).