Intelligent Optimization of the Film-to-Fiber Ratio of a Degradable Braided Bicomponent Ureteral Stent

Abstract

:1. Introduction

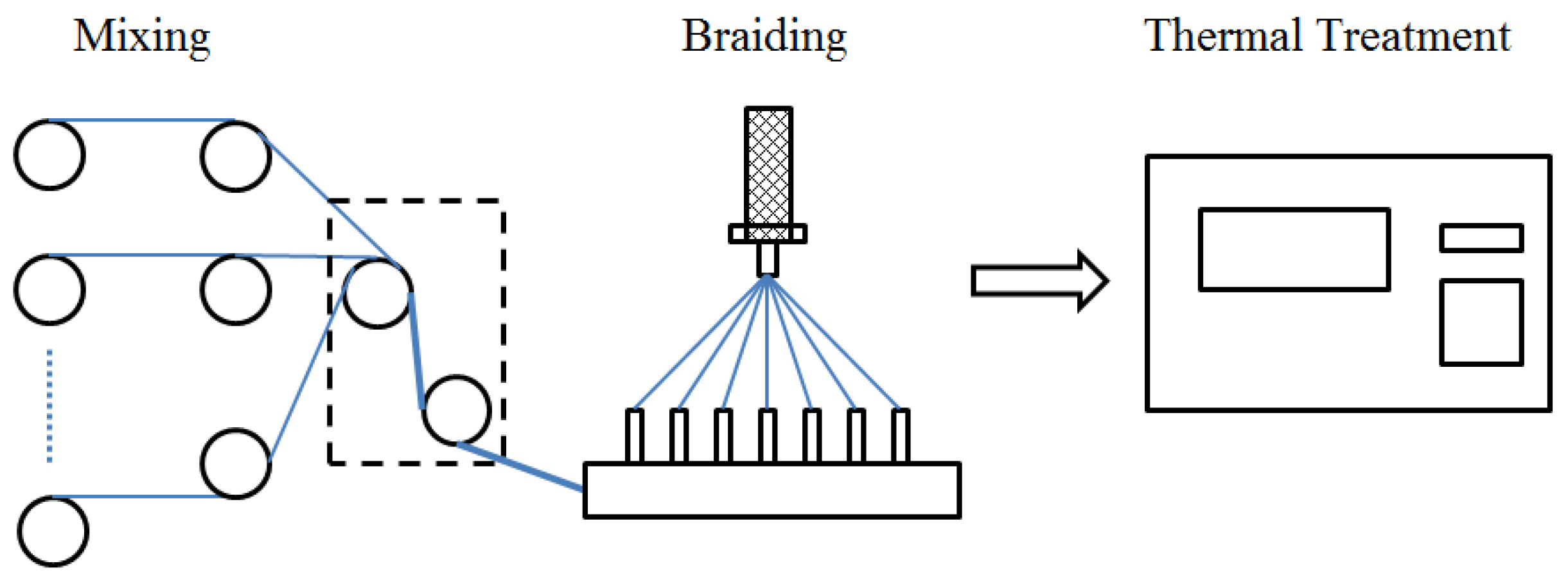

2. Bicomponent Braided Ureteral Stent Modeling

2.1. Materials and Samples

| Samples | PGA (%) | PGLA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 100 |

| 3 | 50 | 50 |

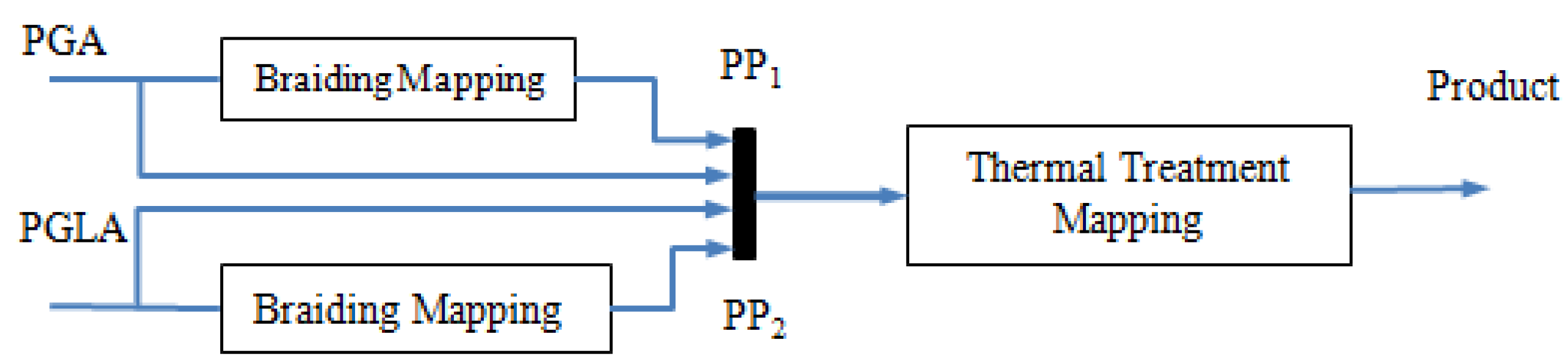

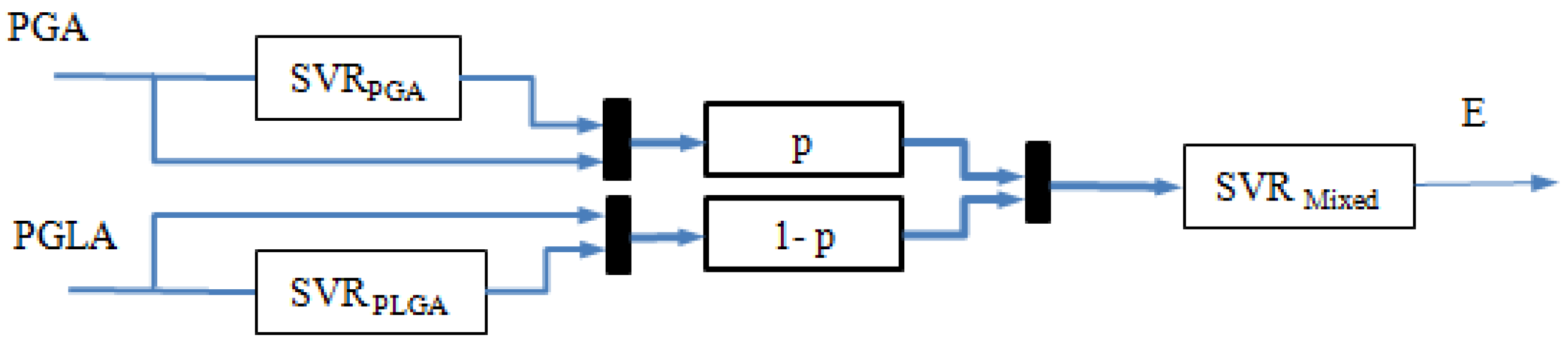

2.2. Hierarchical SVM Model

2.3. Filter Design

3. The Optimal Mixing Ratio

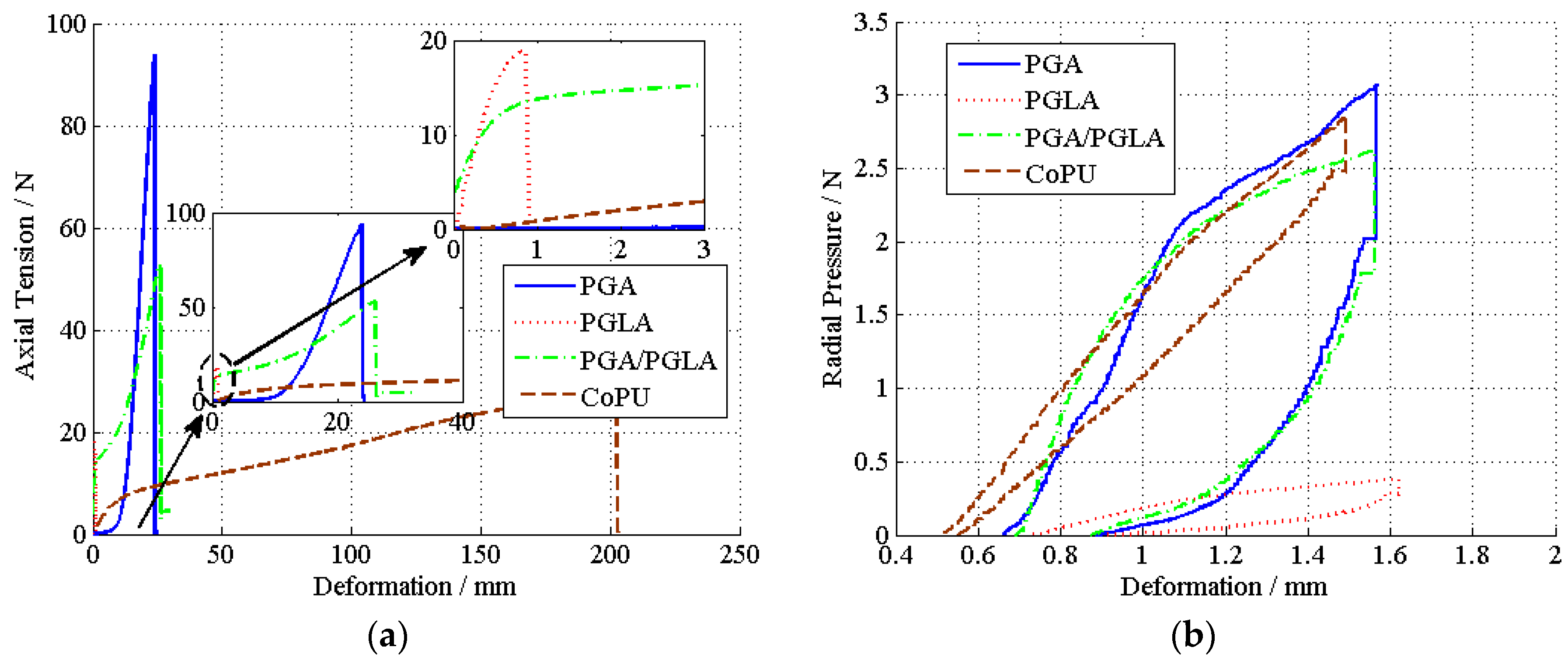

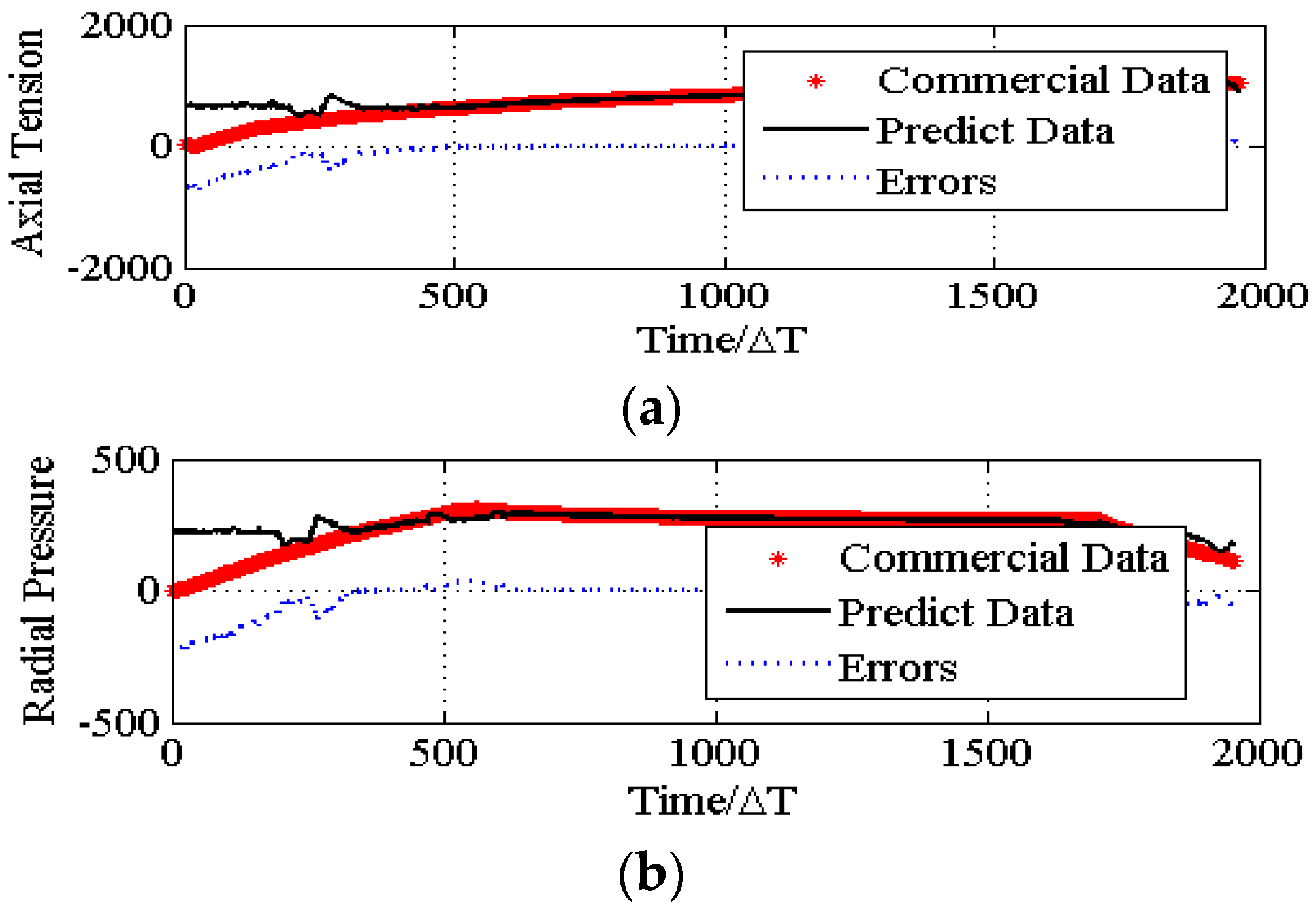

3.1. Property Evaluation of Bicomponent Ureteral Stents

3.2. Problems in the Optimization of the Component Proportion

3.3. Searching the Optimal Solution via PSO

4. Experiments and Simulations

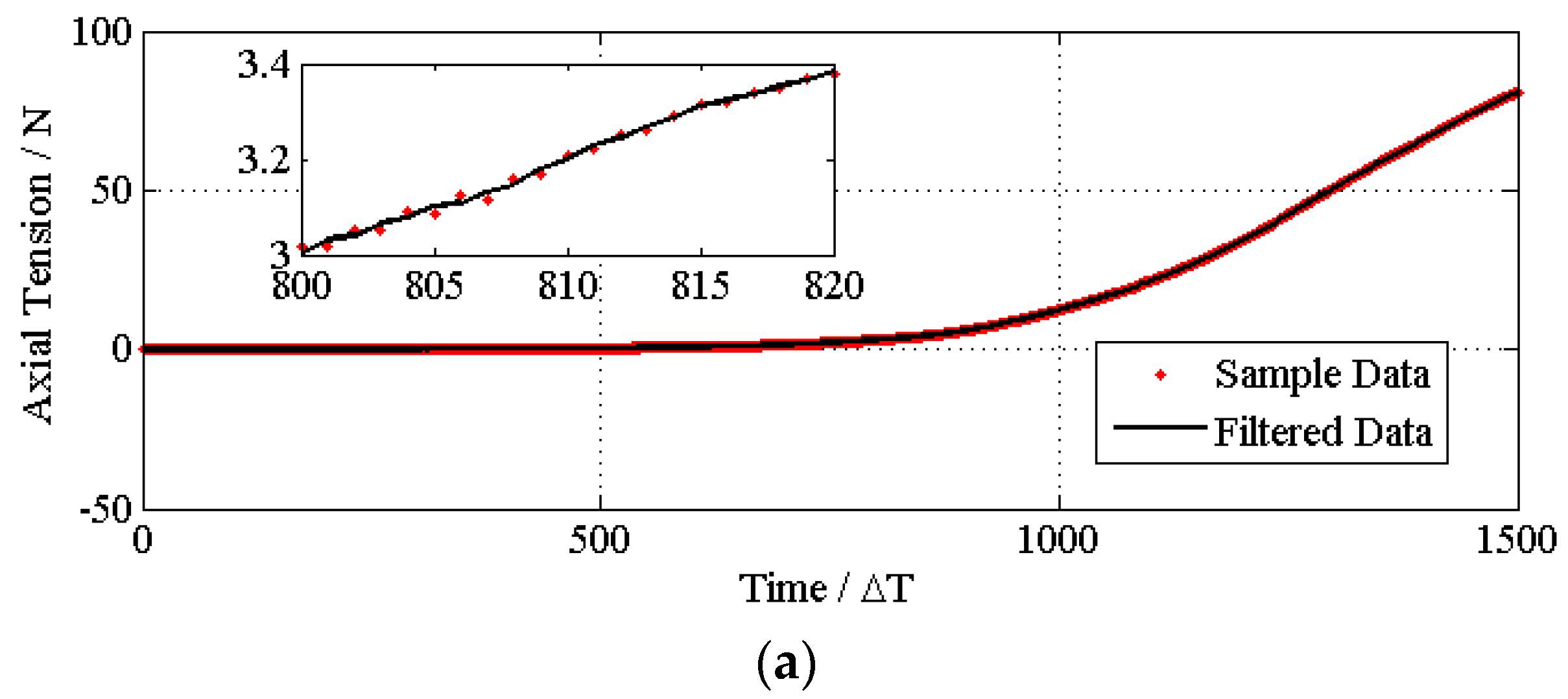

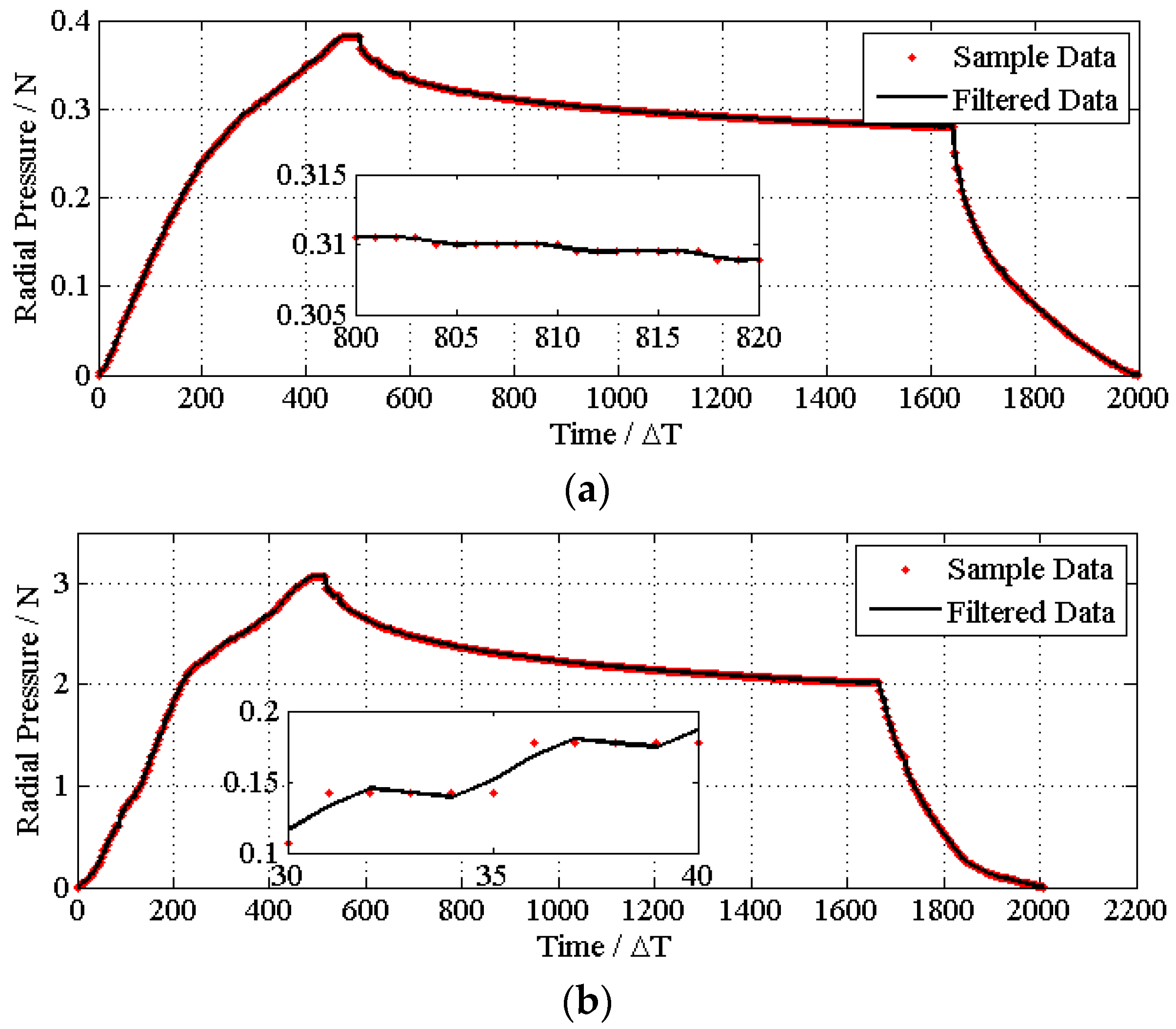

4.1. Experiments and Data Smoothing

- (1)

- Place a specimen with a length of 5 cm on the stand transversely;

- (2)

- Compress the specimen at a speed of 10 mm/min until 50% of its diameter. The maximum force is considered as the radial compressional force;

- (3)

- After a time period of 10 s, withdraw the probe at a speed of 10 mm/min. The percent of elastic recovery is defined as the ratio of the sum of immediate elastic deformation and delayed elastic deformation over the original diameter of the stent;

- (4)

- Each data point is obtained from three tests.

| Experimental Environment and Parameters | Radial Compressive Property | Axial Tensile Property |

|---|---|---|

| Length × inner diameter (mm × mm) | 50 × 1.6 | 50 × 1.6 |

| Compression/elongation (mm/min) | 10 | 50 |

| Temperature (°C) | 25 | 25 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 65 | 65 |

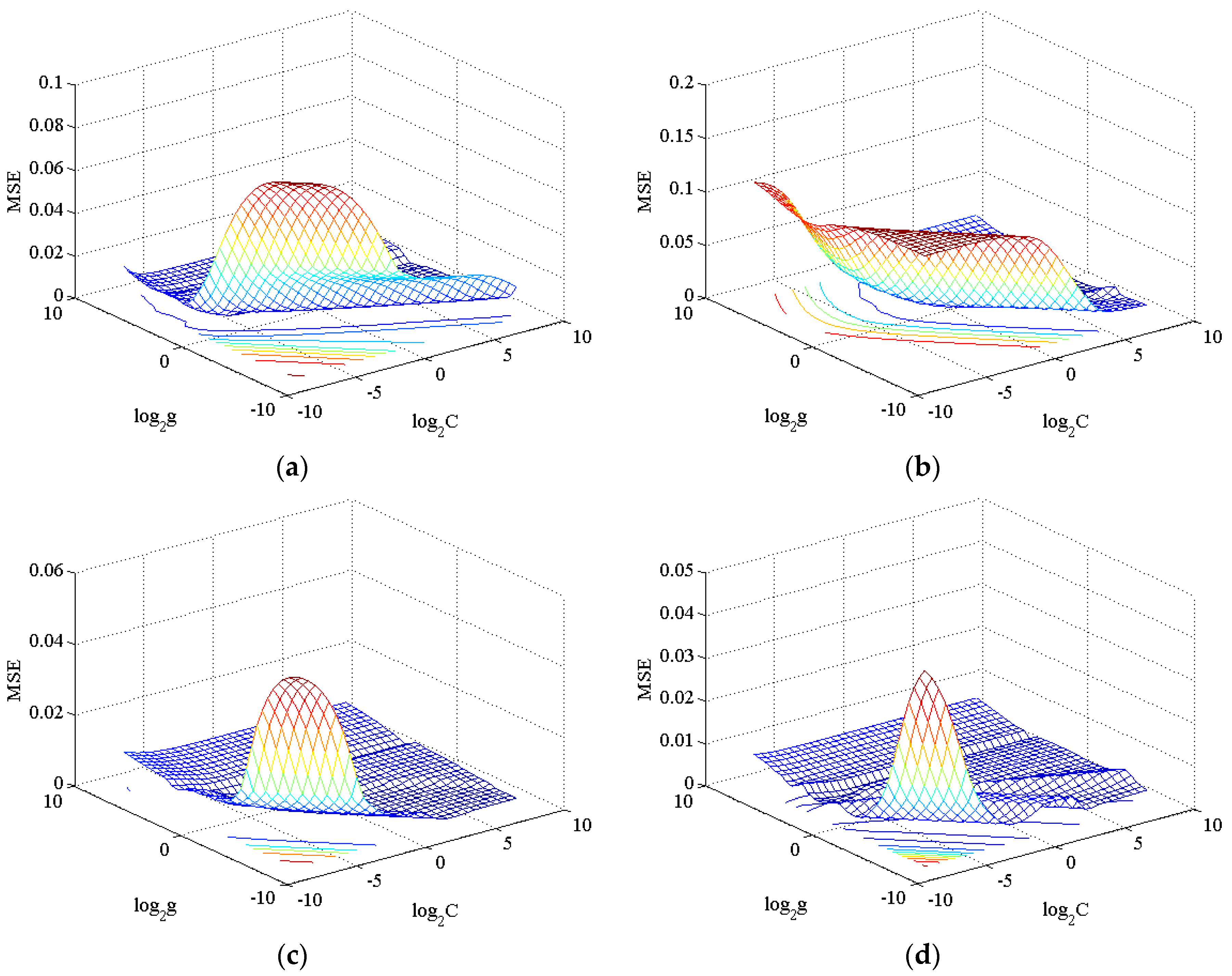

4.2. Determining the Process Parameters

| Parameter | SVRPGA | SVRPGLA | SVRMixed | SVRCoPU * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 1.4142 | 2.8284 | 0.0625 | 0.35355 |

| g | 4 | 0.70711 | 5.6569 | 0.25 |

4.3. The Convergence of the PSO Algorithm.

| Population | Max Generation | η | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 100 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Parameter | Mean | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Iteration | 288 | 6.187 × 10‒6 |

| p* | 0.6989 | 0.3517 |

| fitness | −0.4133 | 0.0270 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tenke, P.; Riedl, C.R.; Jones, G.L.; Williams, G.J.; Stickler, D.; Nagy, E. Bacterial biofilm formation on urologic devices and heparin coating as preventive strategy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2004, 23, S67–S74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lingeman, J.E.; Preminger, G.M.; Berger, Y.; Denstedt, J.D.; Goldstone, L.; Segura, J.W.; Auge, B.K.; Watterson, J.D.; Kuo, R.L. Use of a temporary ureteral drainage stent after uncomplicated ureteroscopy: Results from a phase ii clinical trial. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiko, D.T.; Knudsen, B.E.; Watterson, J.D.; Cadieux, P.A.; Reid, G.; Denstedt, J.D. Urinary tract biomaterials. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 2438–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, R.K.; Pani, K.C.; Neuman, C.; Leonard, F. Polylactic acid for surgical implants. Arch. Surg. 1966, 93, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumiaho, J.; Heino, A.; Tunninen, V.; Ala-Opas, M.; Talja, M.; Välimaa, T.; Törmälä, P. New bioabsorbable polylactide ureteral stent in the treatment of ureteral lesions: An experimental study. J. Endourol. 1999, 13, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinker, H.R. Polyglycolic acid sutures in genitourinary surgery. Urology 1974, 3, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.U.; Lu, Q.I. Study on absorbable suture of biomaterials. Synth. Fiber China 2007, 38, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, S.; Javadpour, N.; Wade, C.; Terrill, R. Biodegradable ureteral grafts in dogs. Invest. Urol. 1978, 16, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Assimos, D.G.; Smith, C.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Carone, F.A.; Grayhack, J.T. Efficacy of polyglycolic acid (pga) tubing stents in ureteroureterostomies. Urol. Res. 1984, 12, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.C.; Wang, C.X.; Zheng, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.W. Biocompatibility and biodegradation characteristics of poly (l-lactide-co-glycolide) in vivo and in vitro. J. Jilin Univ. (Med. Ed.) 2005, 31, 526–529. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Zhang, L.; Hou, Y.C.; Chen, Q.H.; Jiang, F.M.; Zhang, H.F.; Wang, C.X. The fabrication and properties of co-polymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) ureteral stent by electrospining. J. China Med. Univ. 2011, 40, 784–751. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.C.; Wang, C.X.; Chen, X.S.; Zhagn, B.G. Ureteral in situ biocompatibility of l-lactide-glycolic acid copolymer 80:20 stent. J. Jilin Univ. Med. Ed. 2006, 32, 762–765. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, B.H.; Lange, D. In vivo evaluation of the third generation biodegradable stent: A novel approach to avoiding the forgotten stent syndrome. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, B.H.; Lange, D.; Paterson, R.F.; Hendlin, K.; Monga, M.; Clinkscales, K.W.; Shalaby, S.W.; Hadaschik, B.A. Next generation biodegradable ureteral stent in a yucatan pig model. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zou, T.; Huang, Y.C.; Shang, Y.F.; Wang, F.J.; Xie, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.Z.; Chen, F. An enhanced textile gradually degradable ureteral stent. Patent zl201310038995.5; China, 11 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Wang, W.Z.; Shang, Y.F.; Zou, T.; Wang, F.J.; Zhou, J.M.; Xie, H.; Guan, G.P.; Huang, Y.C.; et al. A braided gradually degradable ureteral stent and its preparation. Patent application 201110241408.4; China, 16 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, T.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, F.; King, M.W. A resorbable bicomponent braided ureteral stent with improved mechanical performance. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 38, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Hao, K.; Ding, Y. The bi-directional prediction of carbon fiber production using a combination of improved particle swarm optimization and support vector machine. Materials 2014, 8, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Hao, K.; Wang, T.; Liu, X. Performance prediction of differential fibers with a bi-directional optimization approach. Materials 2013, 6, 5967–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.; de-Prado-Cumplido, M. Svm multiregression for non linear channel estimation in multiple-input multiple-output systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2004, 52, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boche, H.; Pohl, V. Structural properties of the wiener filter—Stability, smoothness properties, and fir approximation behavior. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2006, 52, 4272–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendlin, K.; Dockendorf, K.; Horn, C.; Pshon, N.; Lund, B.; Monga, M. Ureteral stents: Coil strength and durometer. Urology 2006, 68, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardis, H.K.; Kroeger, R.M.; Morton, J.J.; Donovan, J.M. Comparative evaluation of materials used for internal ureteral stents. J. Endourol. 1993, 7, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.Y.; Stein, R.J.; Landsittel, D.; Davies, B.J.; Cuellar, D.C.; Hrebinko, R.L.; Tarin, T.; Averch, T.D. 15-year experience with the management of extrinsic ureteral obstruction with indwelling ureteral stents. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, R.; Kennedy, J.; Blackwell, T. Particle swarm optimization an overview. Swarm Intell. 2007, 1, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Li, F.; Ding, Y.; Zou, T.; Wang, L.; Hao, K. Intelligent Optimization of the Film-to-Fiber Ratio of a Degradable Braided Bicomponent Ureteral Stent. Materials 2015, 8, 7563-7577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8115397

Liu X, Li F, Ding Y, Zou T, Wang L, Hao K. Intelligent Optimization of the Film-to-Fiber Ratio of a Degradable Braided Bicomponent Ureteral Stent. Materials. 2015; 8(11):7563-7577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8115397

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoyan, Feng Li, Yongsheng Ding, Ting Zou, Lu Wang, and Kuangrong Hao. 2015. "Intelligent Optimization of the Film-to-Fiber Ratio of a Degradable Braided Bicomponent Ureteral Stent" Materials 8, no. 11: 7563-7577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8115397