Structural, Transport and Electrochemical Properties of LiFePO4 Substituted in Lithium and Iron Sublattices (Al, Zr, W, Mn, Co and Ni)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phosphoolivines Substituted in Li Sublattice by Al3+, Zr4+ and W6+ Cations

2.1.1. Structural Properties

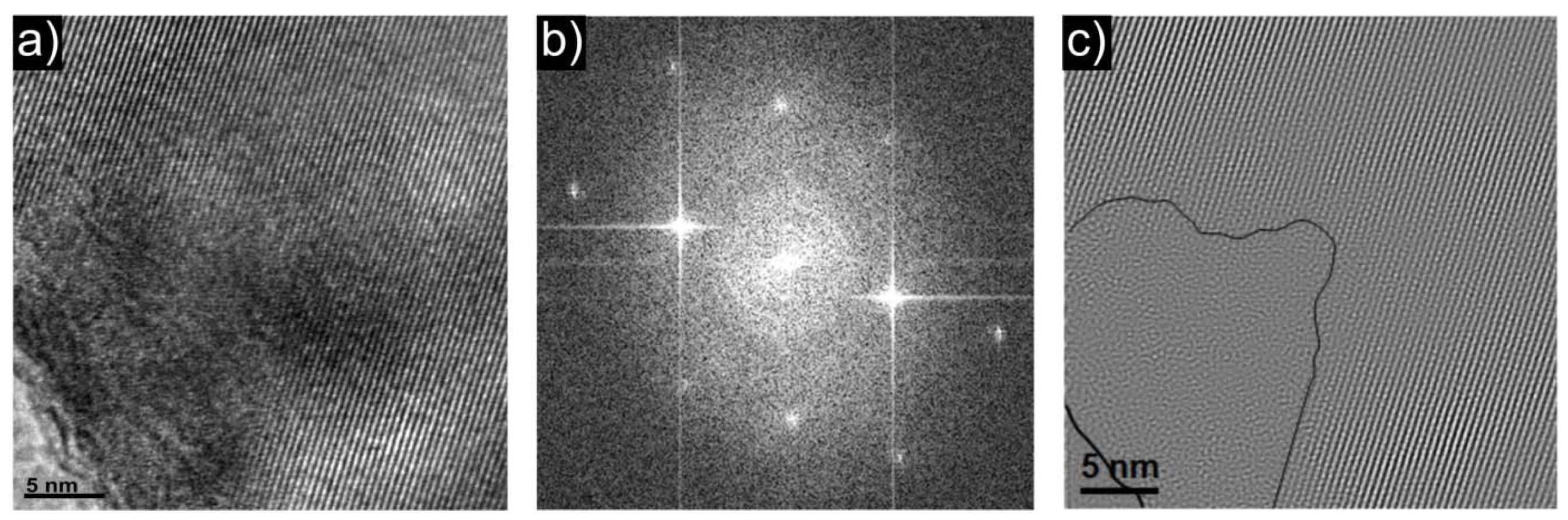

2.1.2. Morphology of LiFePO4 and Li0.97Al0.01FePO4 Powders

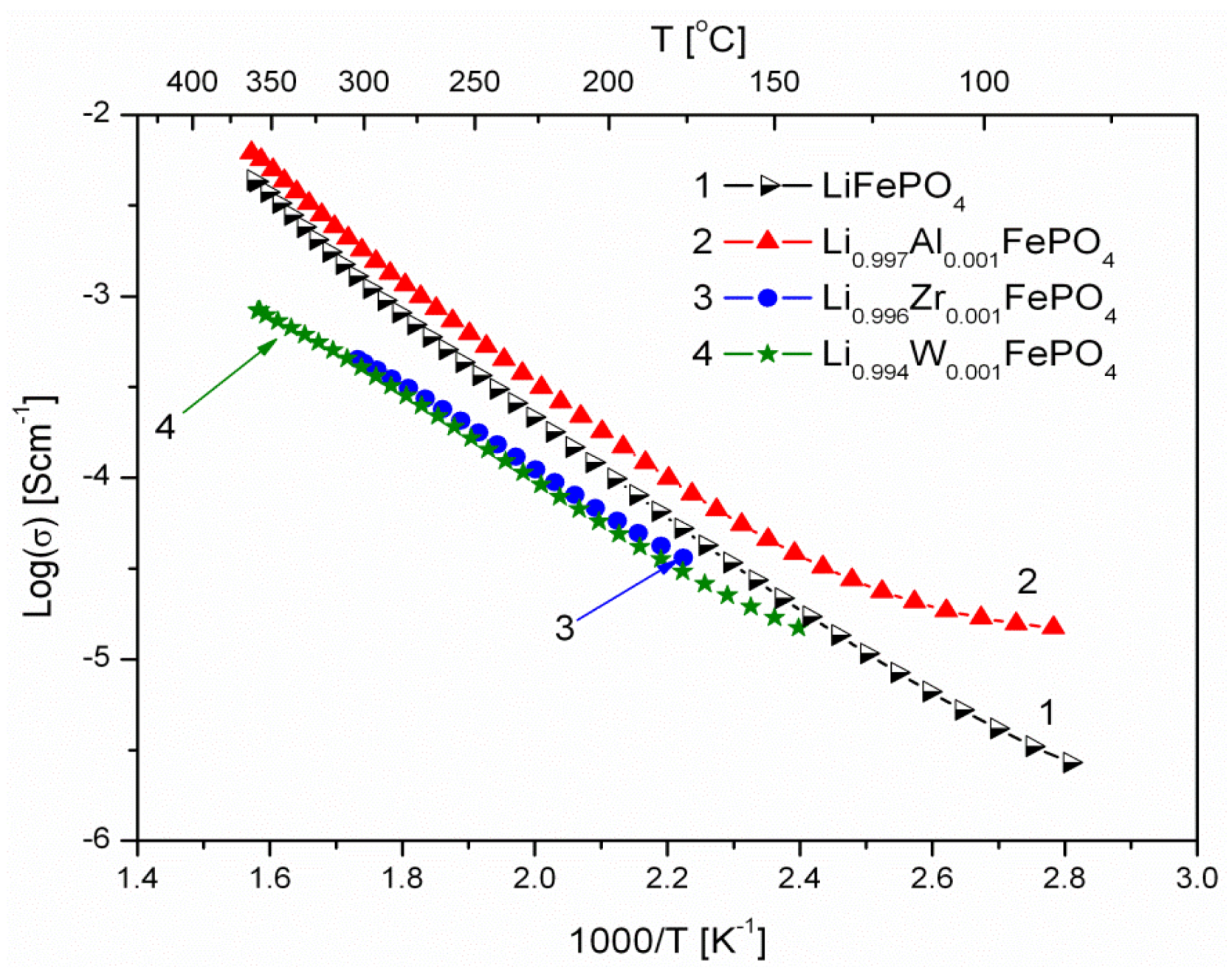

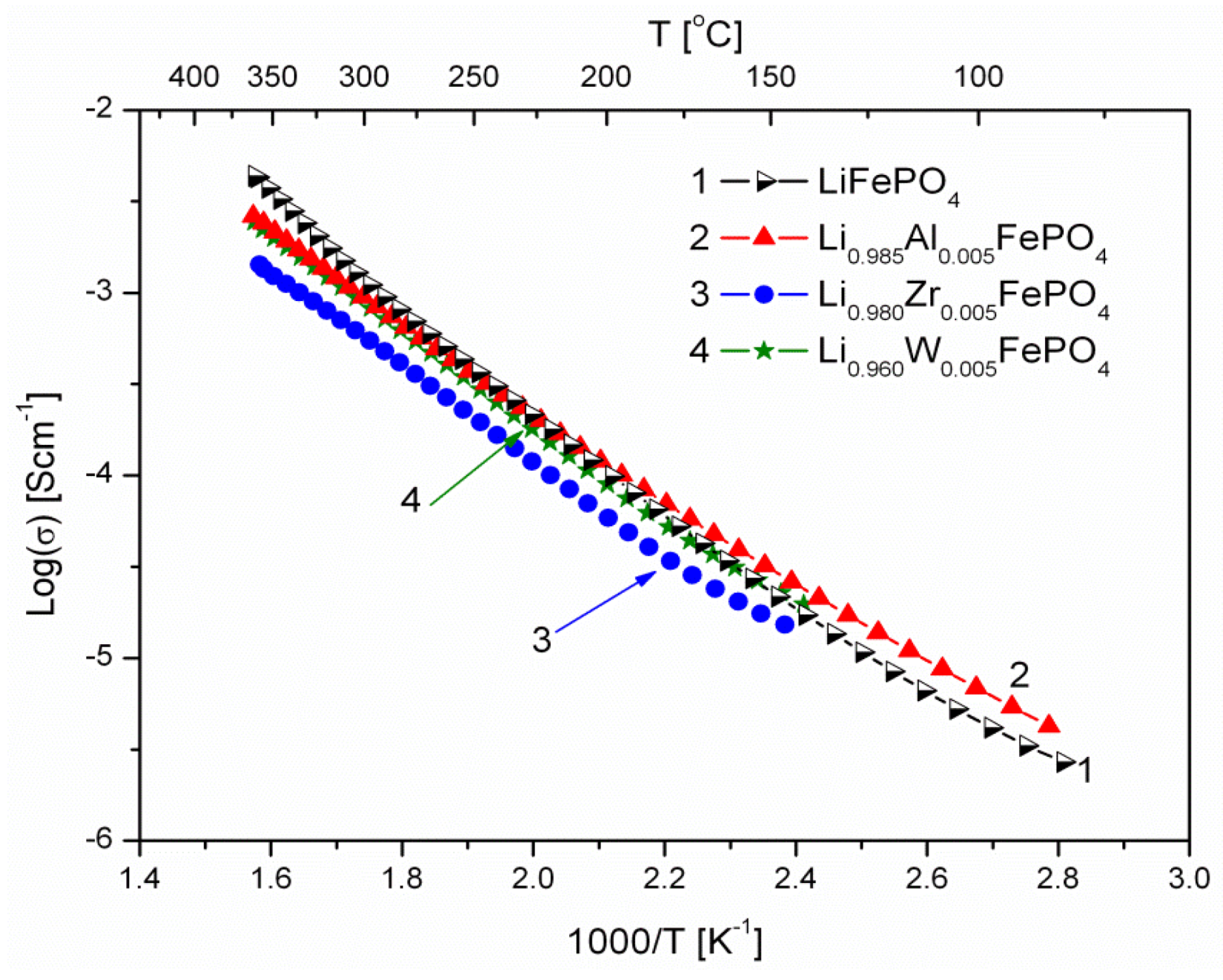

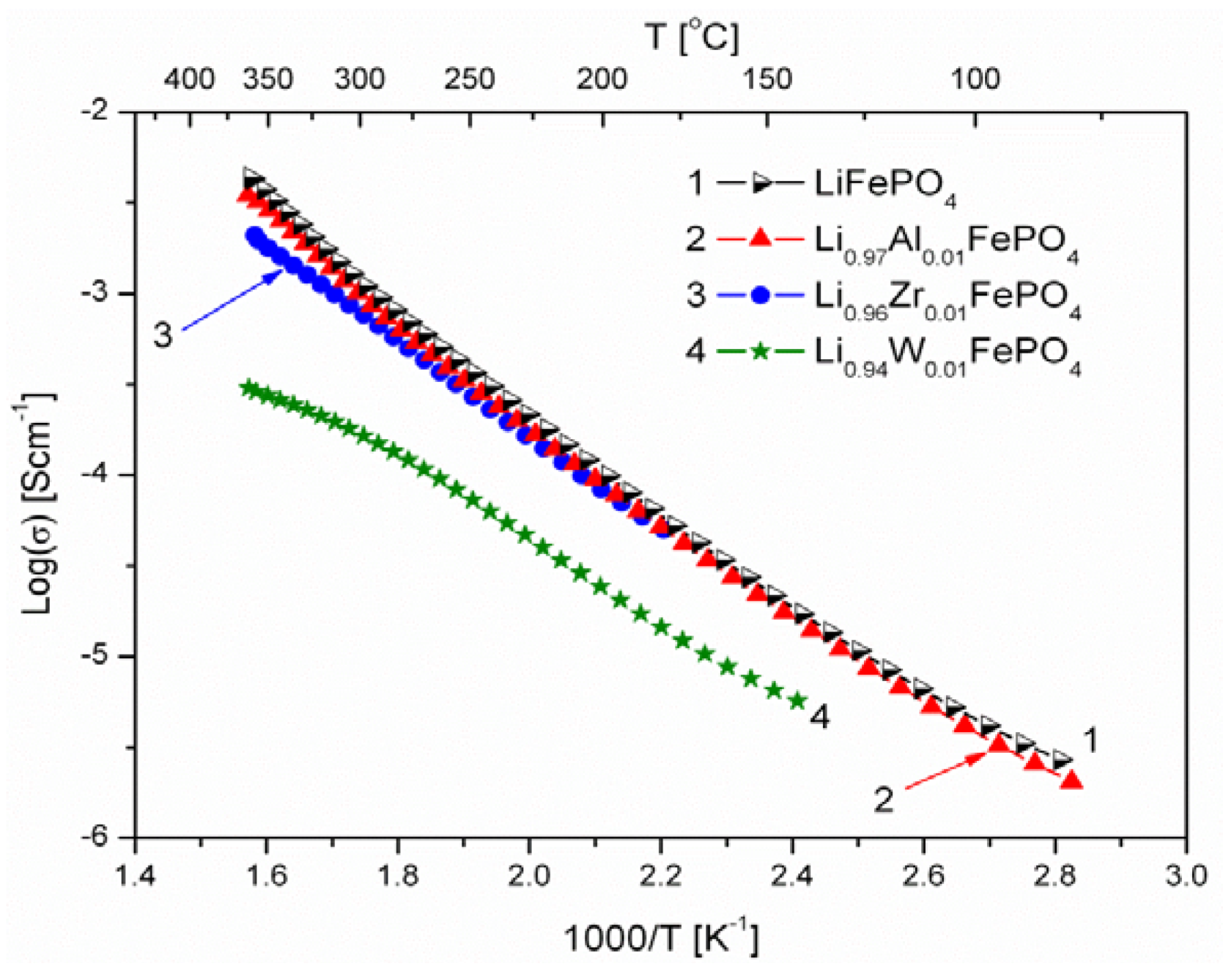

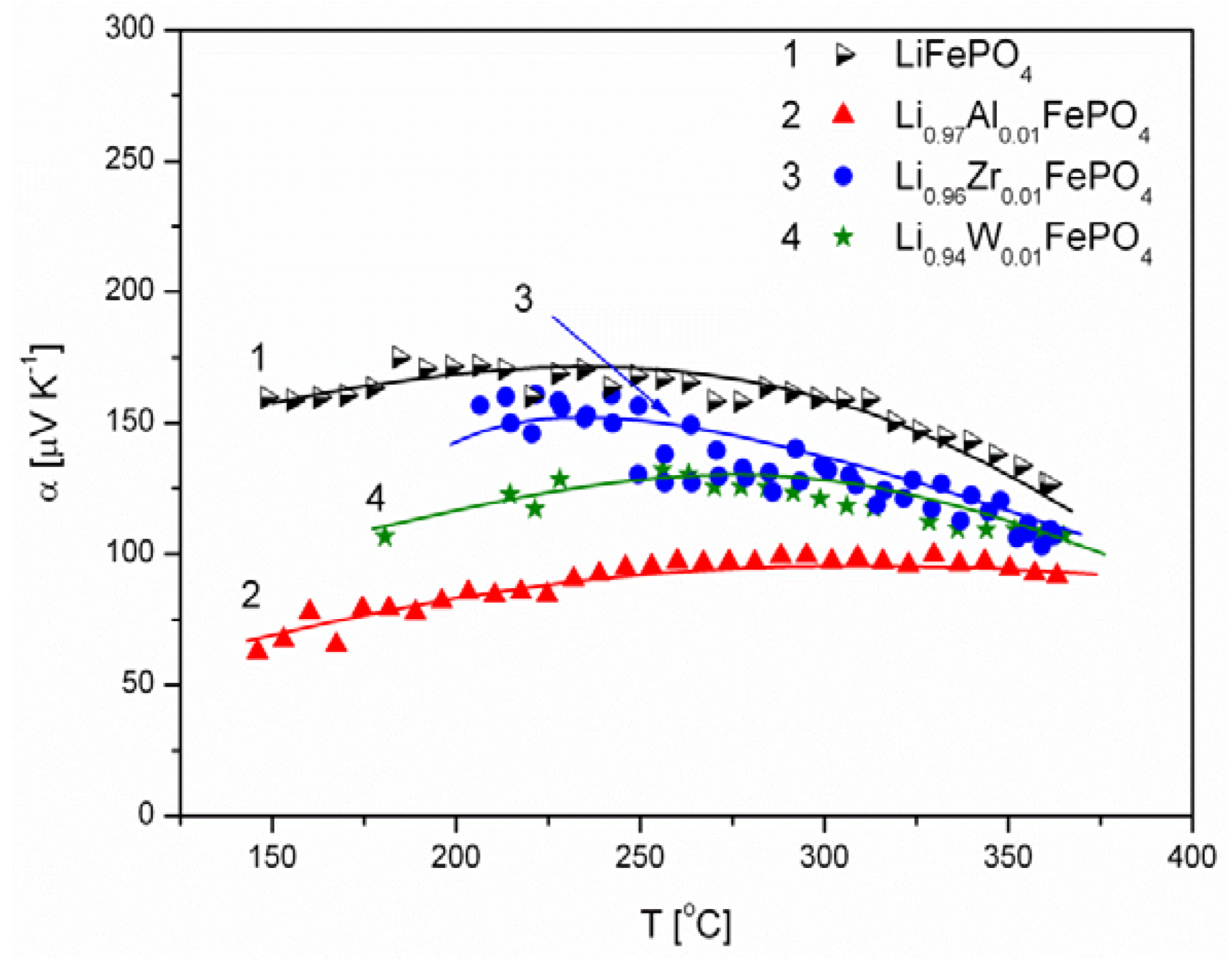

2.1.3. Transport Properties

- concentration and type of dopant have no significant influence on the values of electrical conductivity,

- no critical concentration was observed, for which an effective conduction band could be created as an in Mott-type metal-insulator transition,

- inhomogeneous distribution of dopant elements may also lead to high conductivity values,

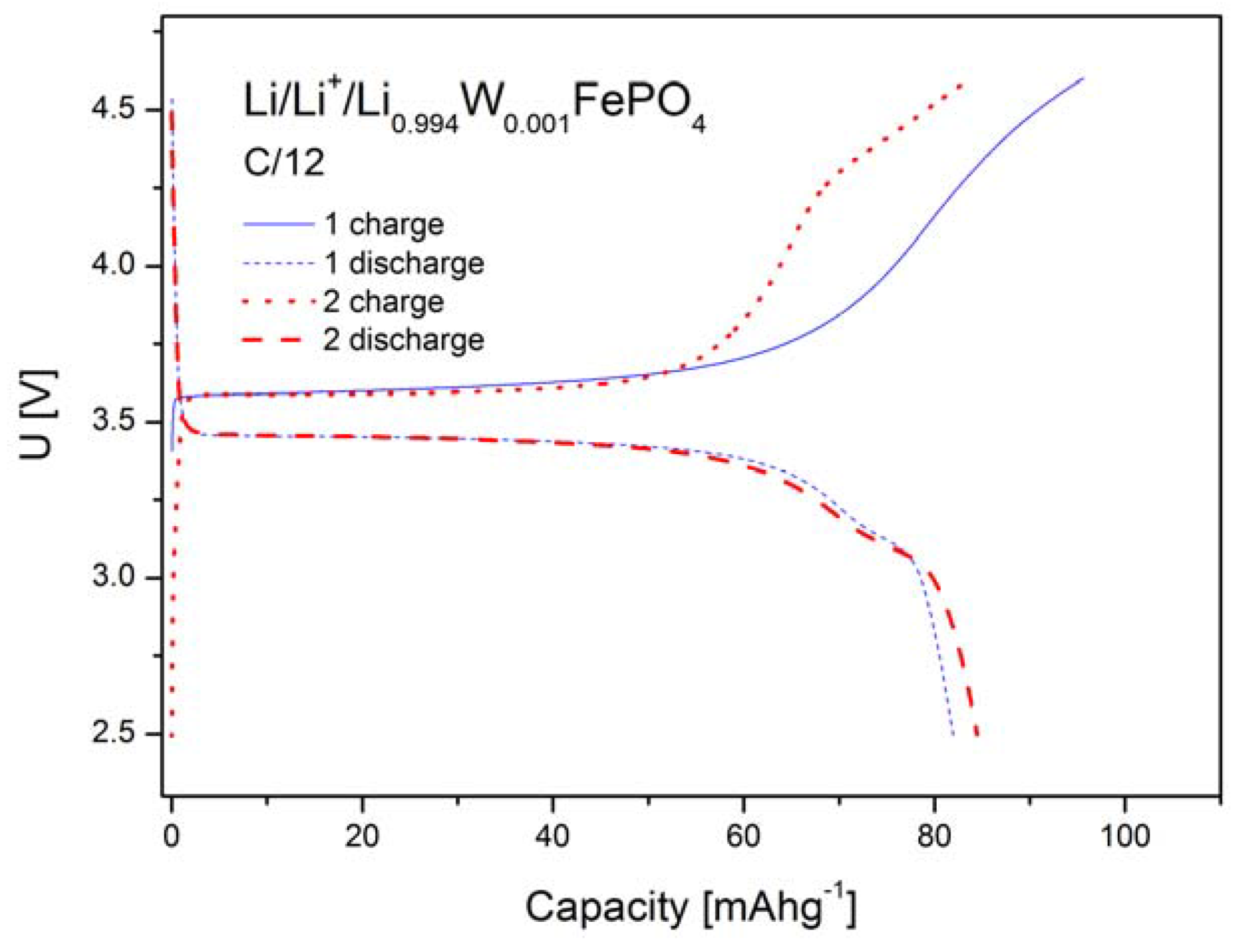

- the delithiation process proceeds as a two-phase type reaction, the same as in the case of insulating LiFePO4 (see the following section).

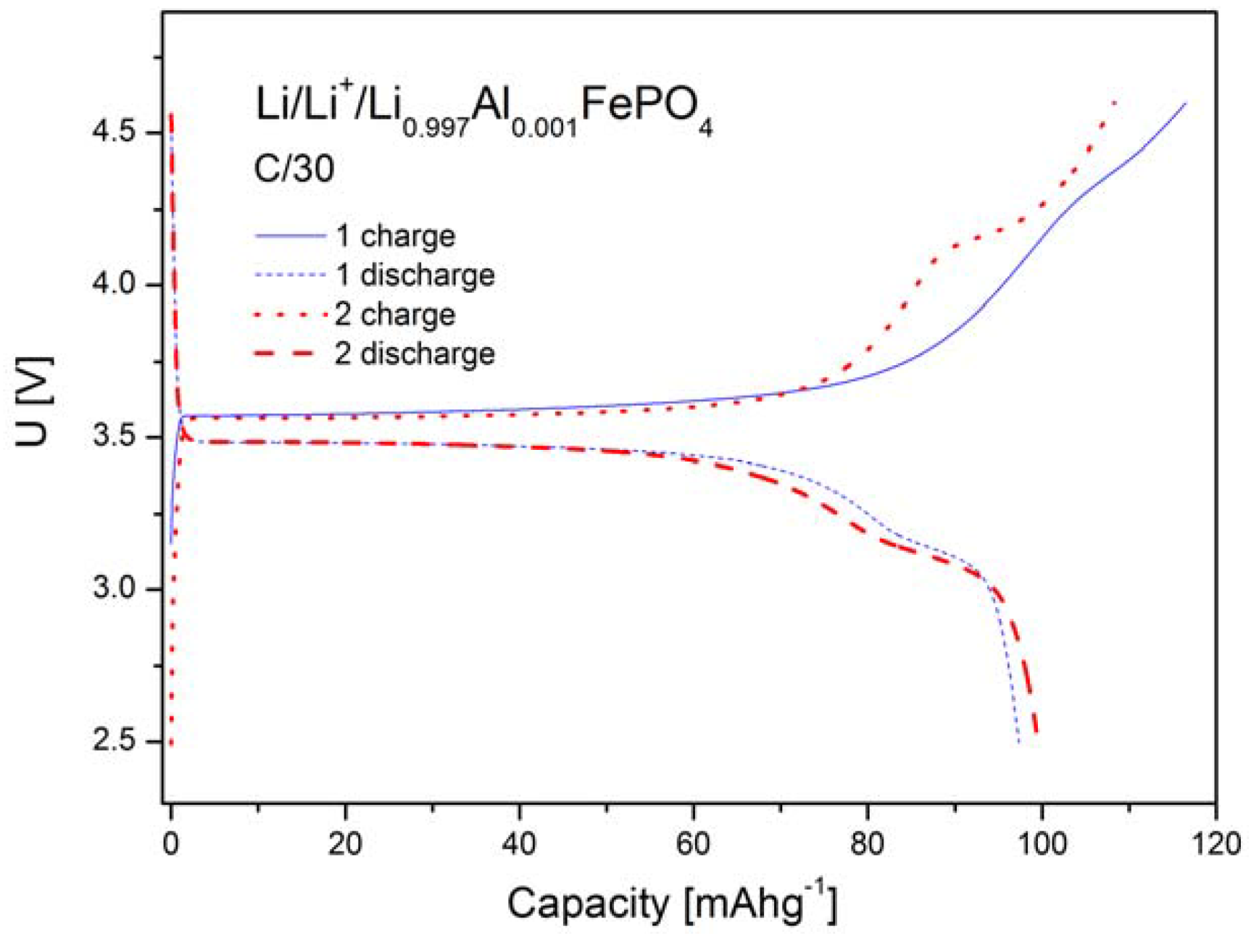

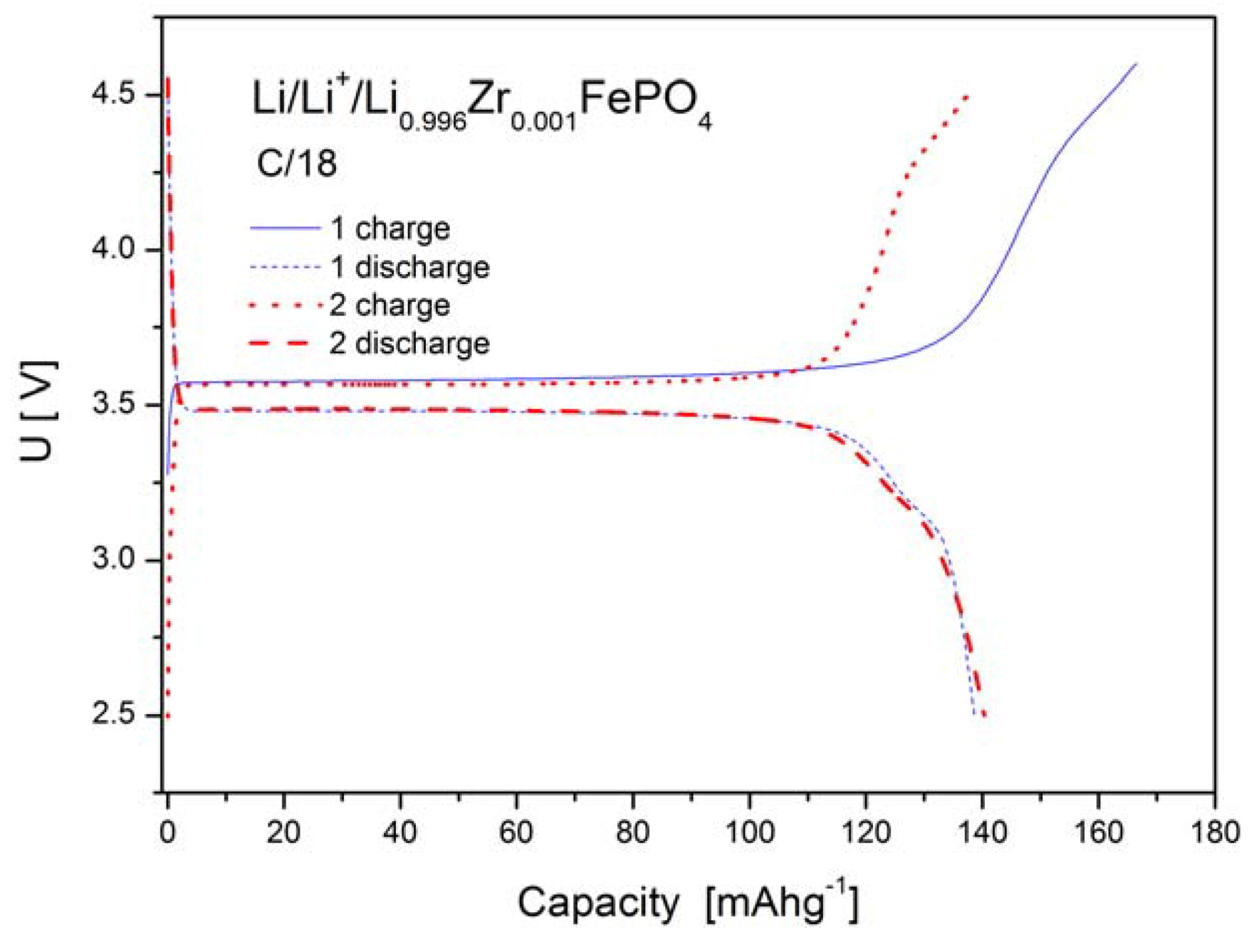

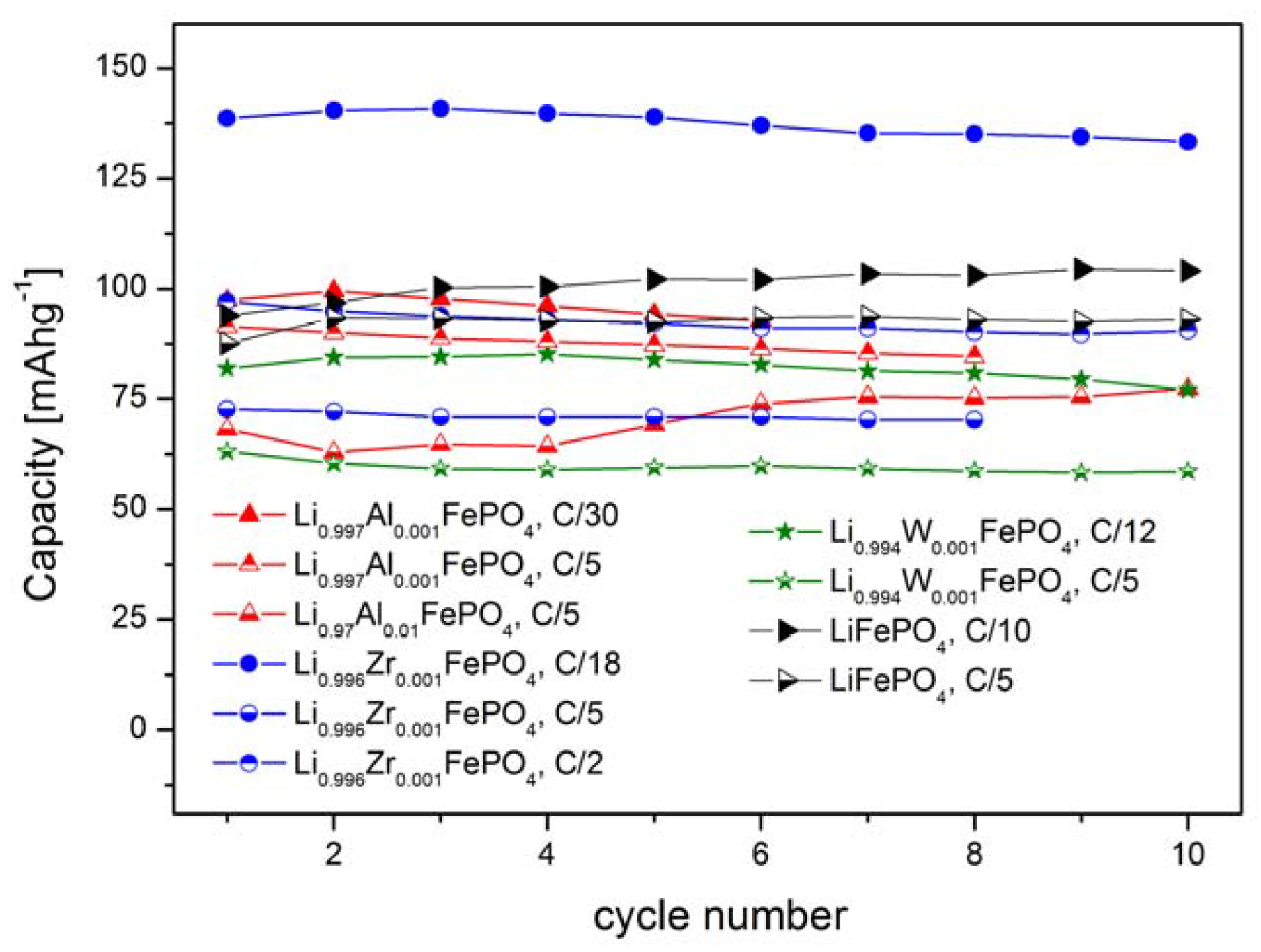

2.1.4. Electrochemical Properties

2.2. LiFePO4 Substituted by Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+ and Cu2+ Cations in the Iron Sublattice

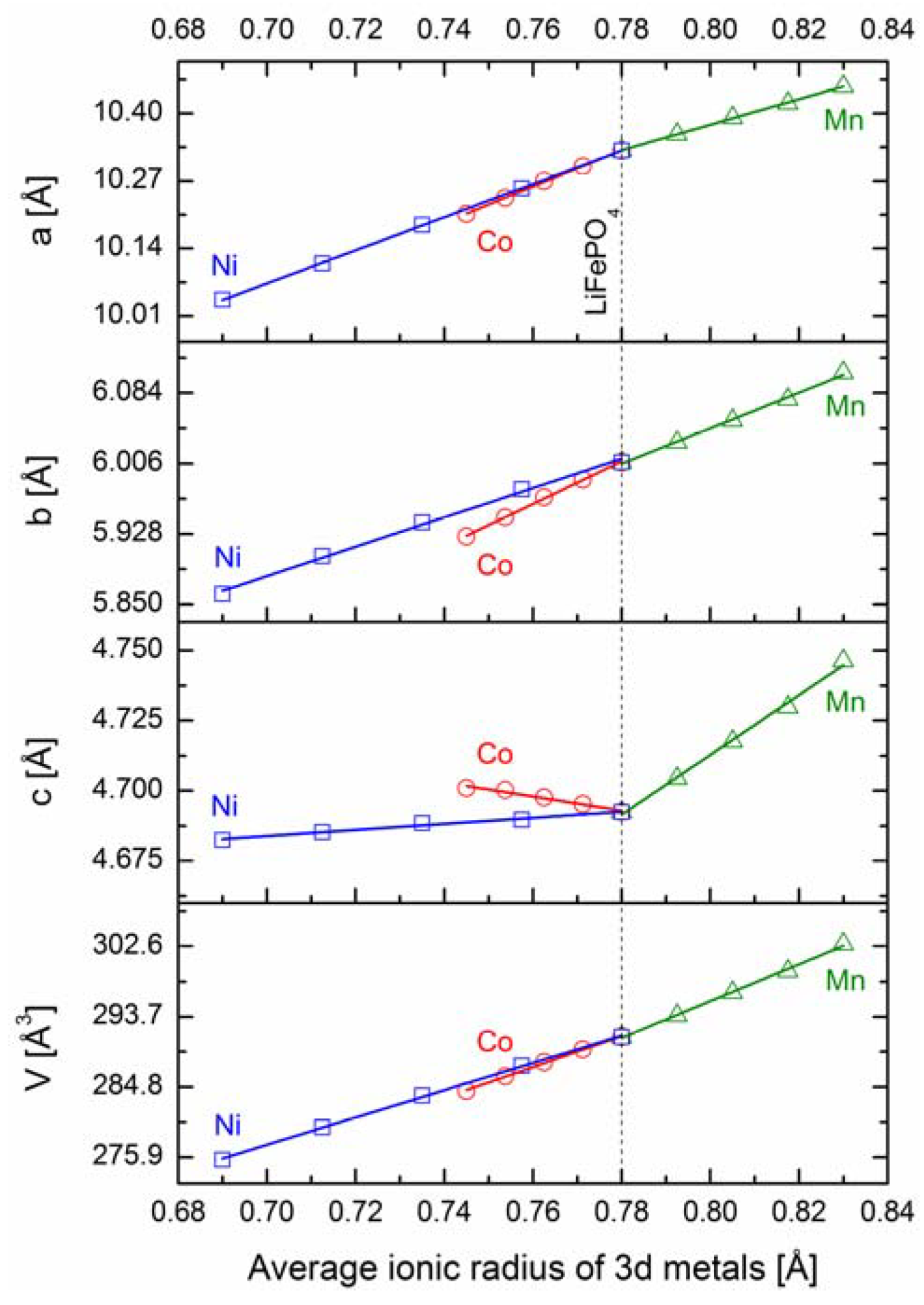

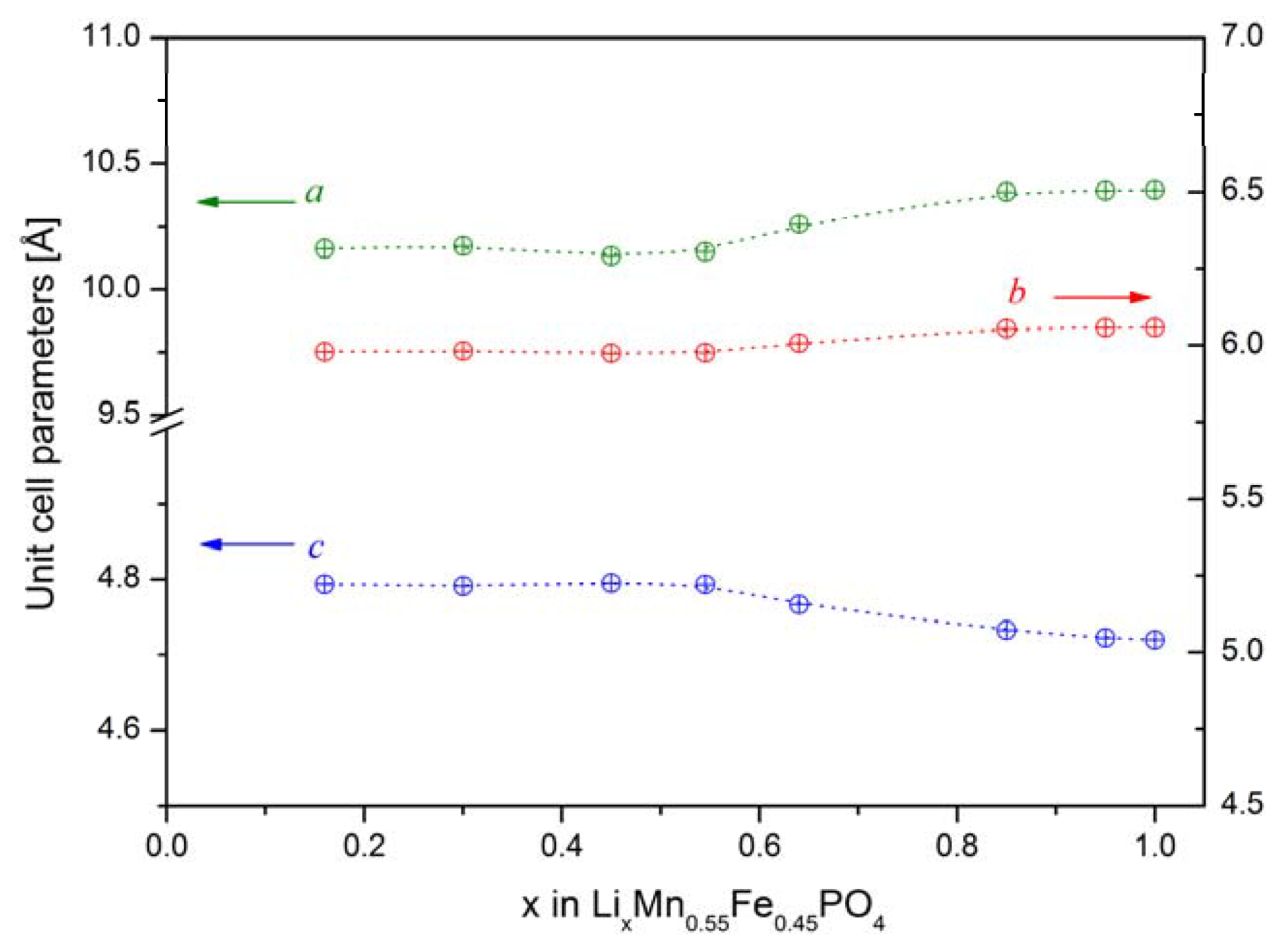

2.2.1. Structural Properties

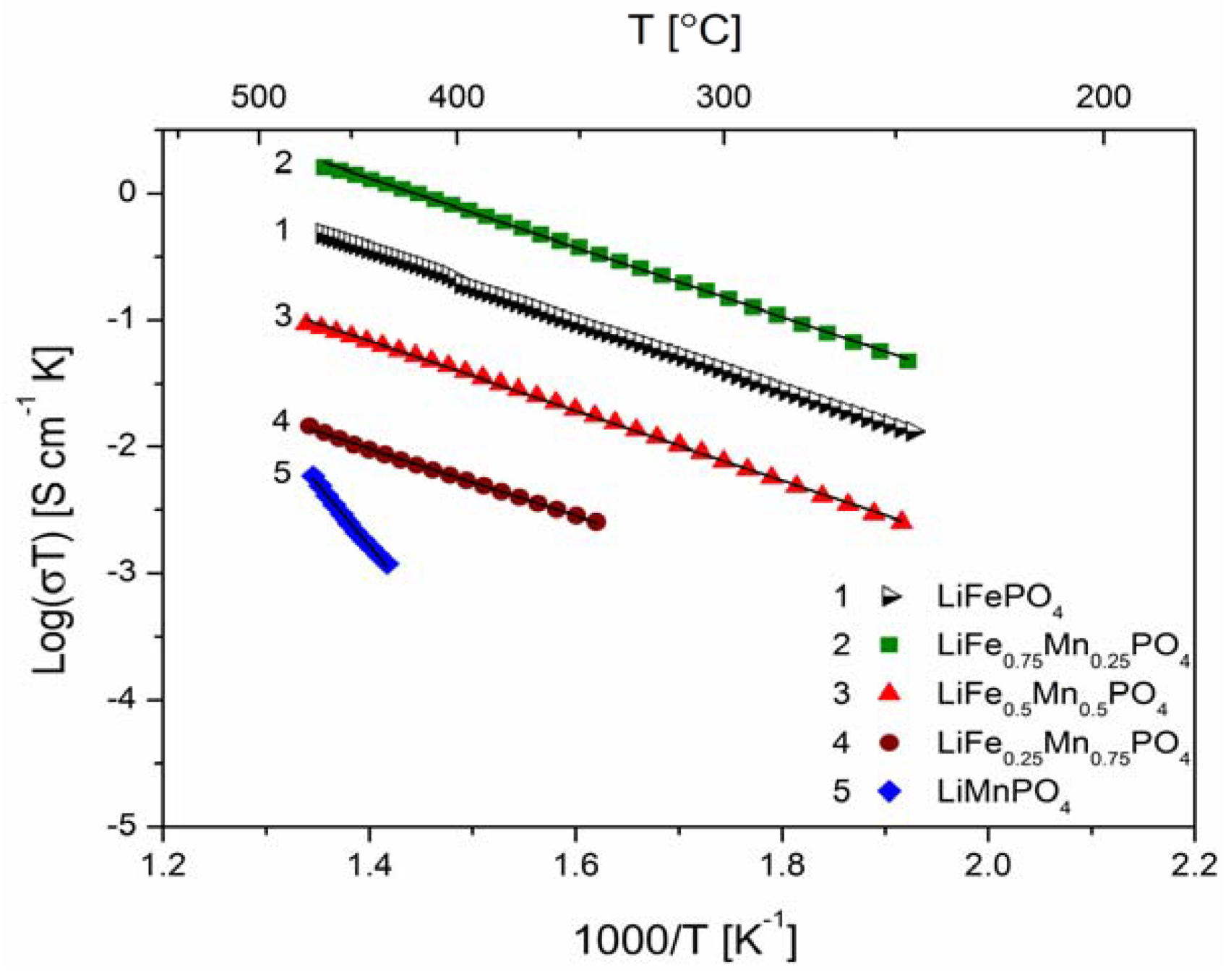

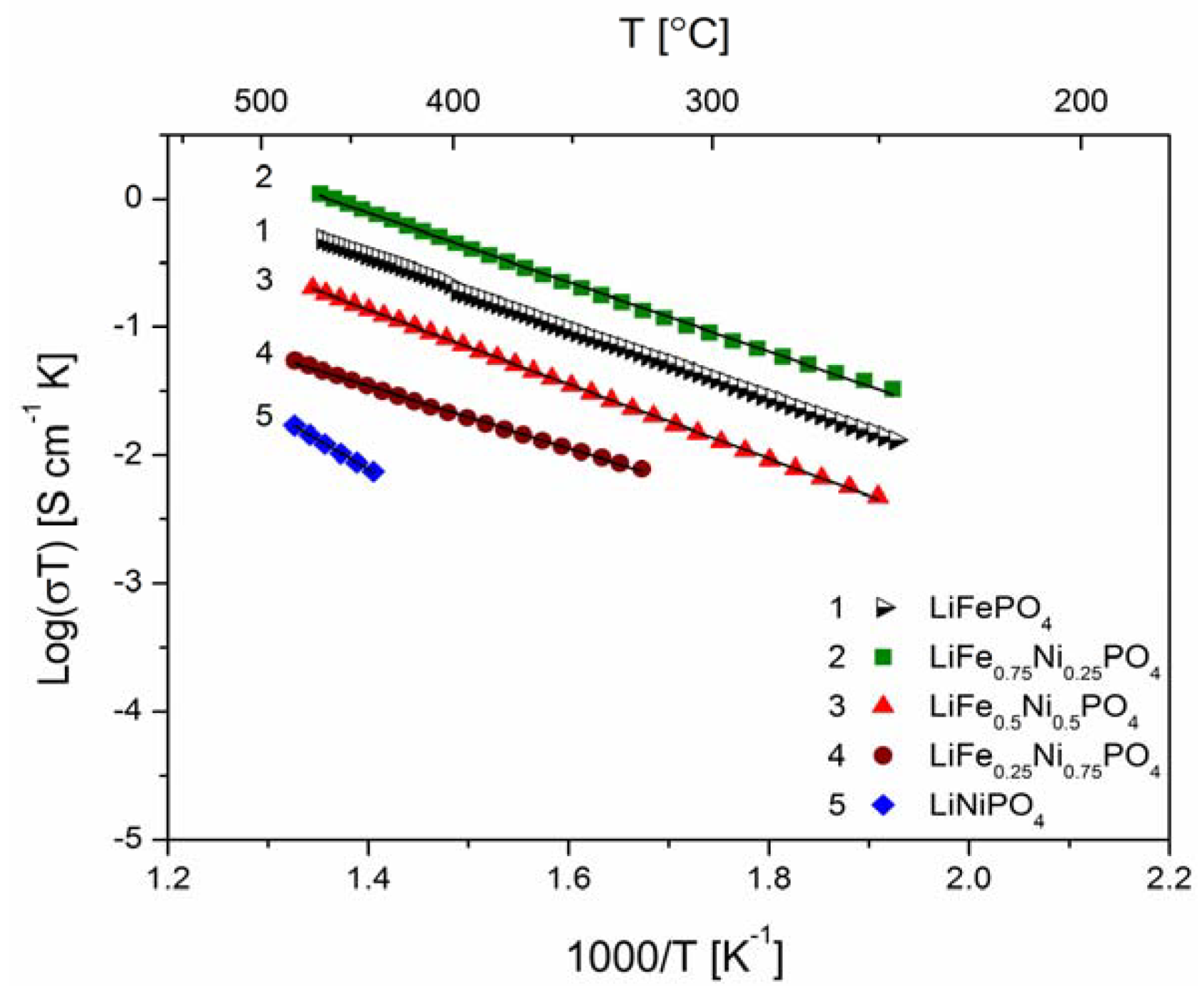

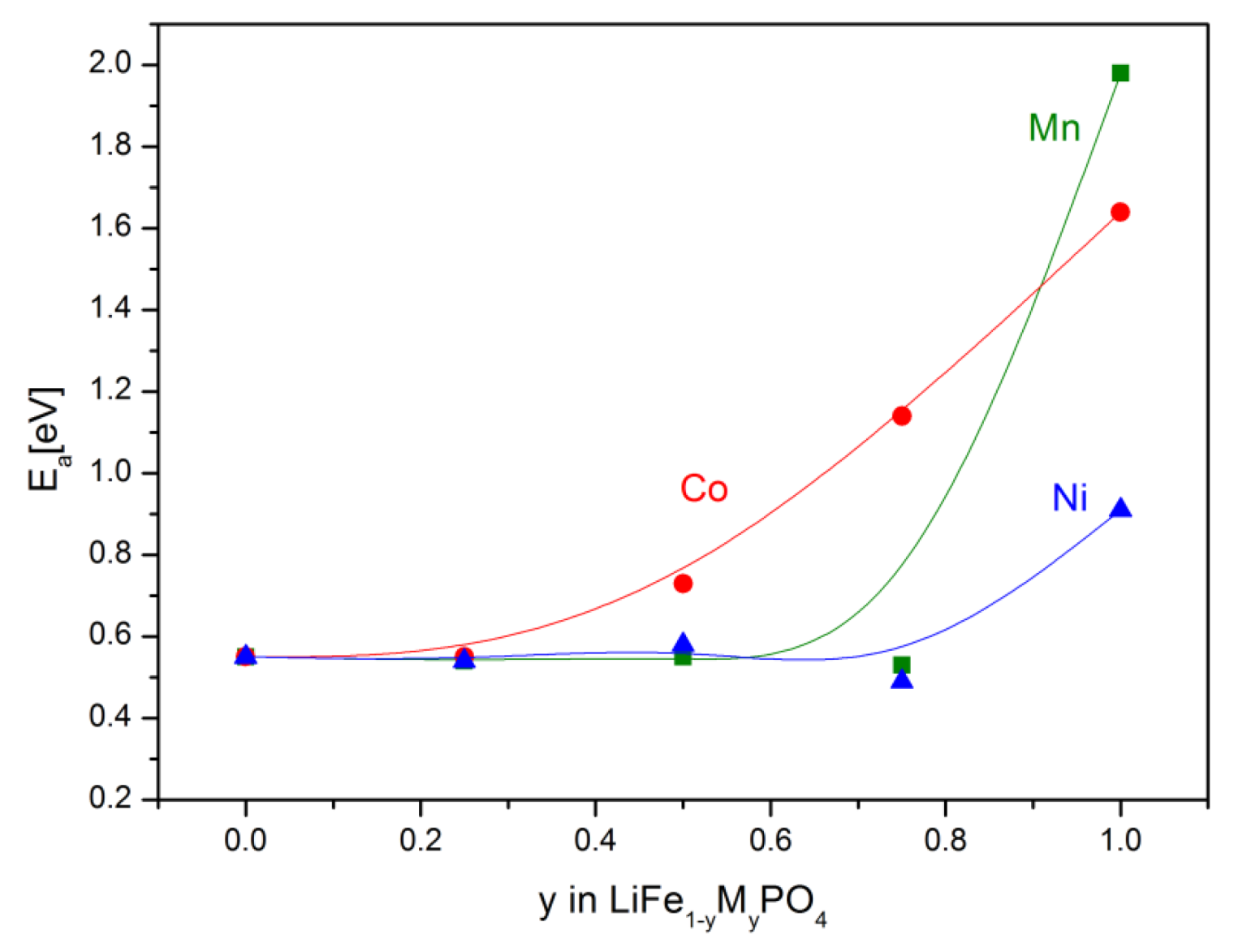

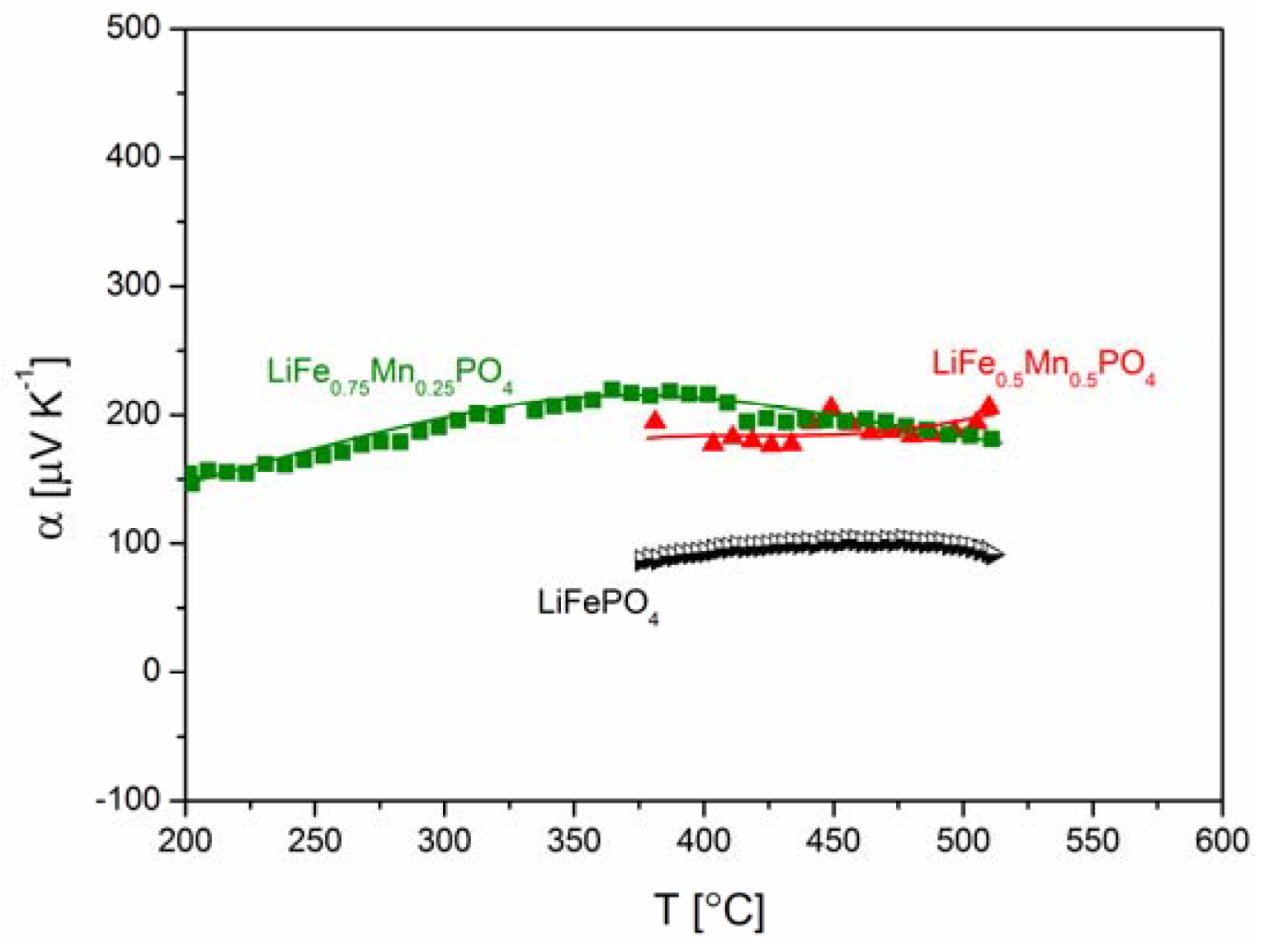

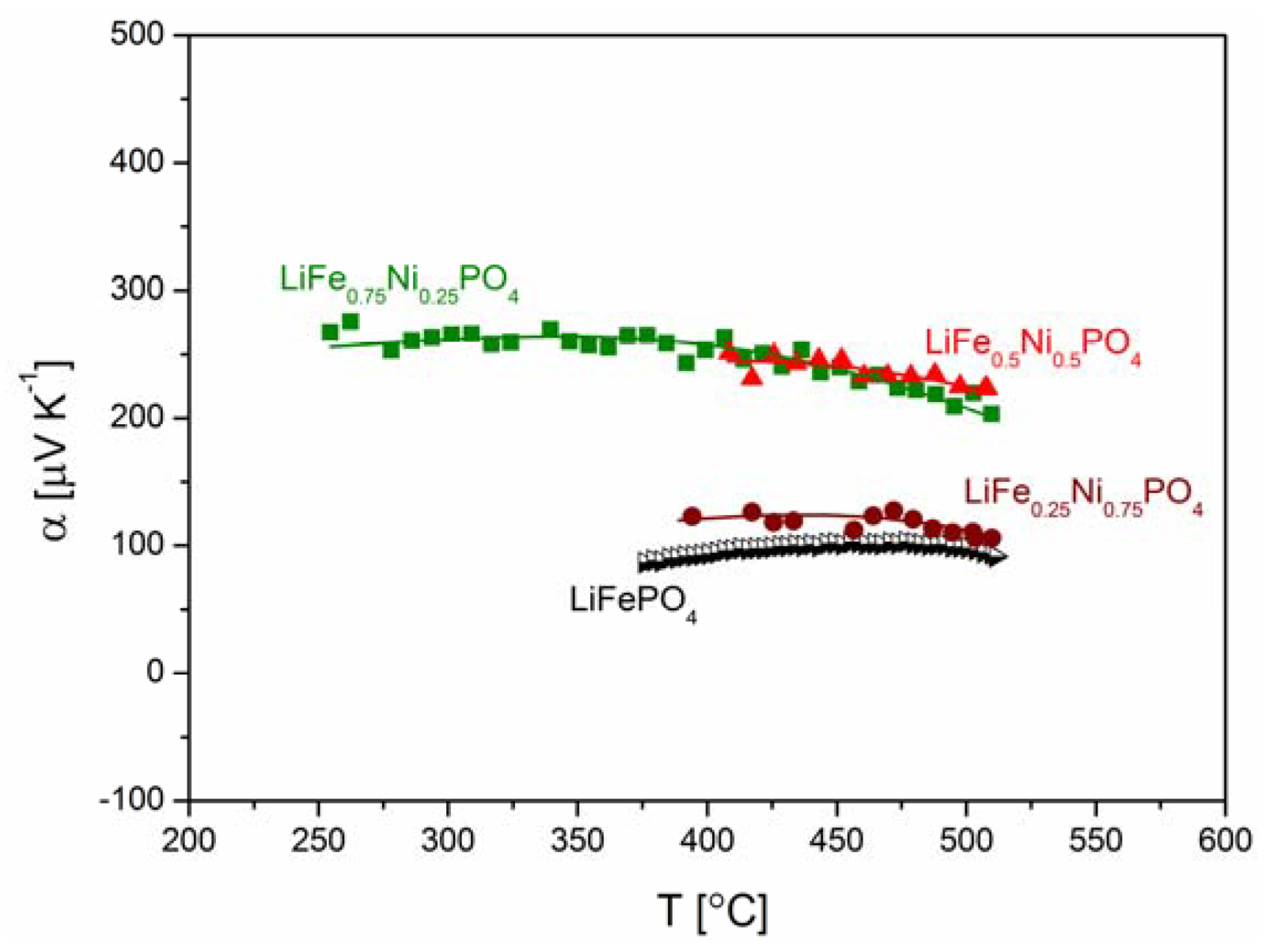

2.2.2. Transport Properties

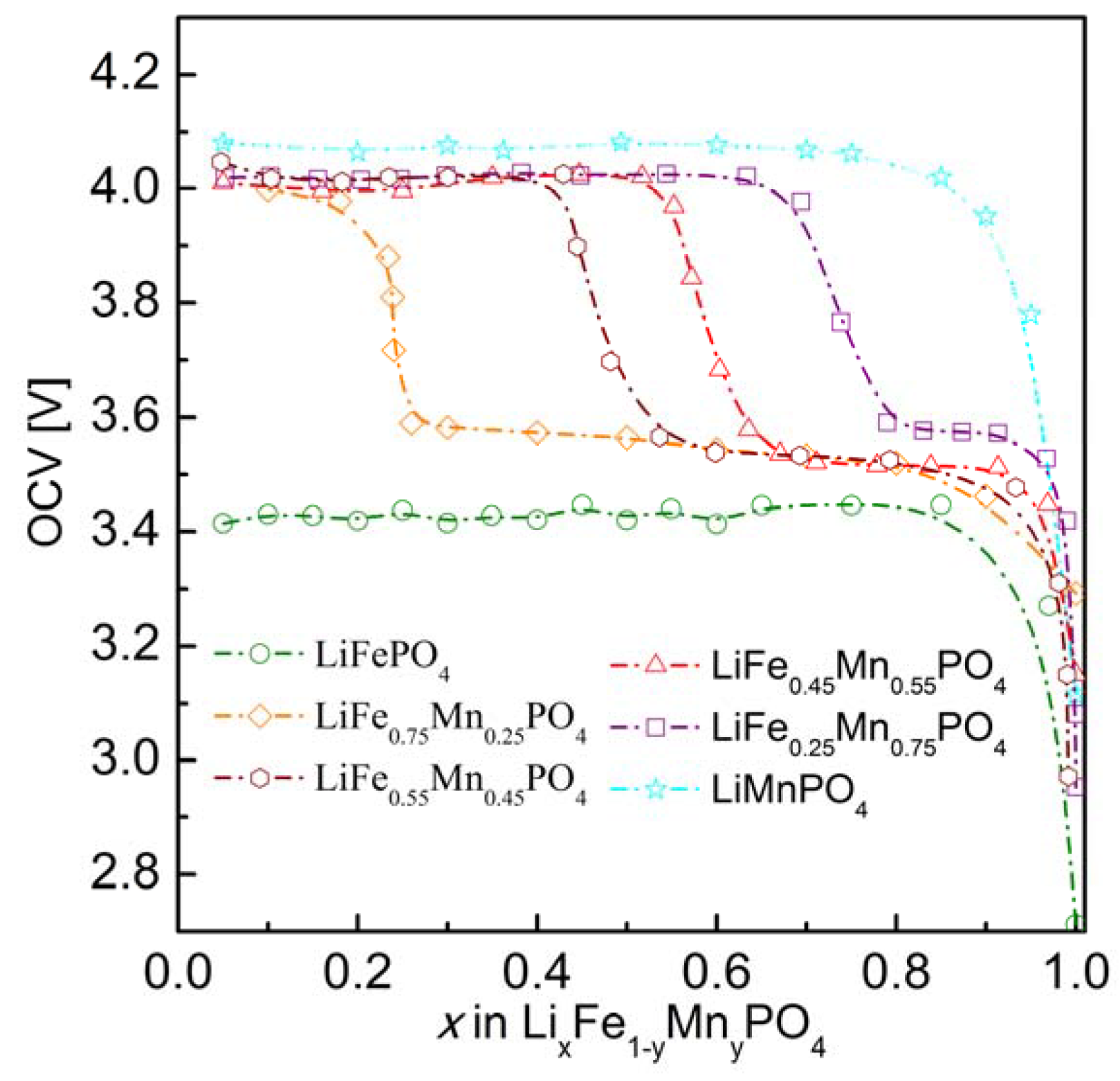

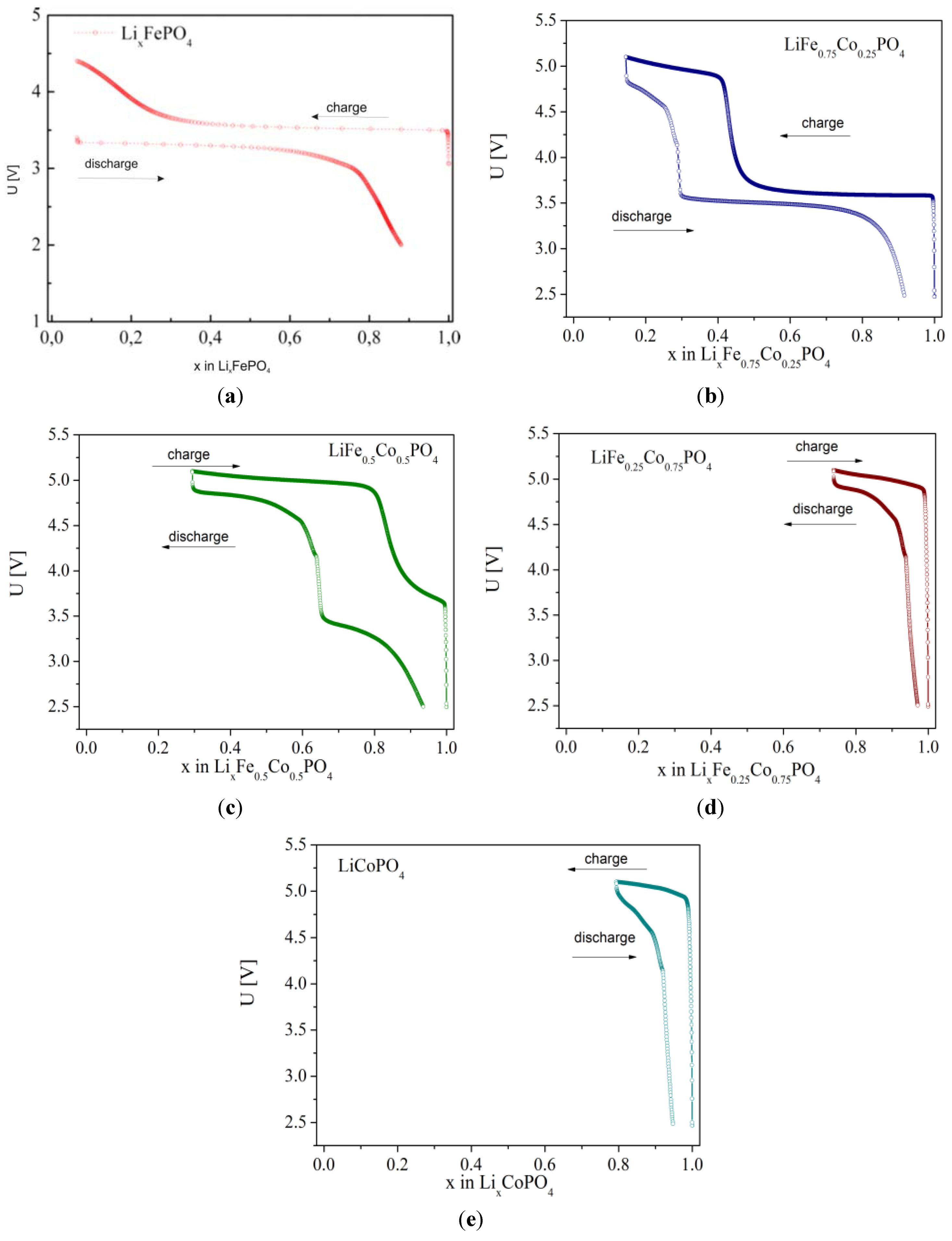

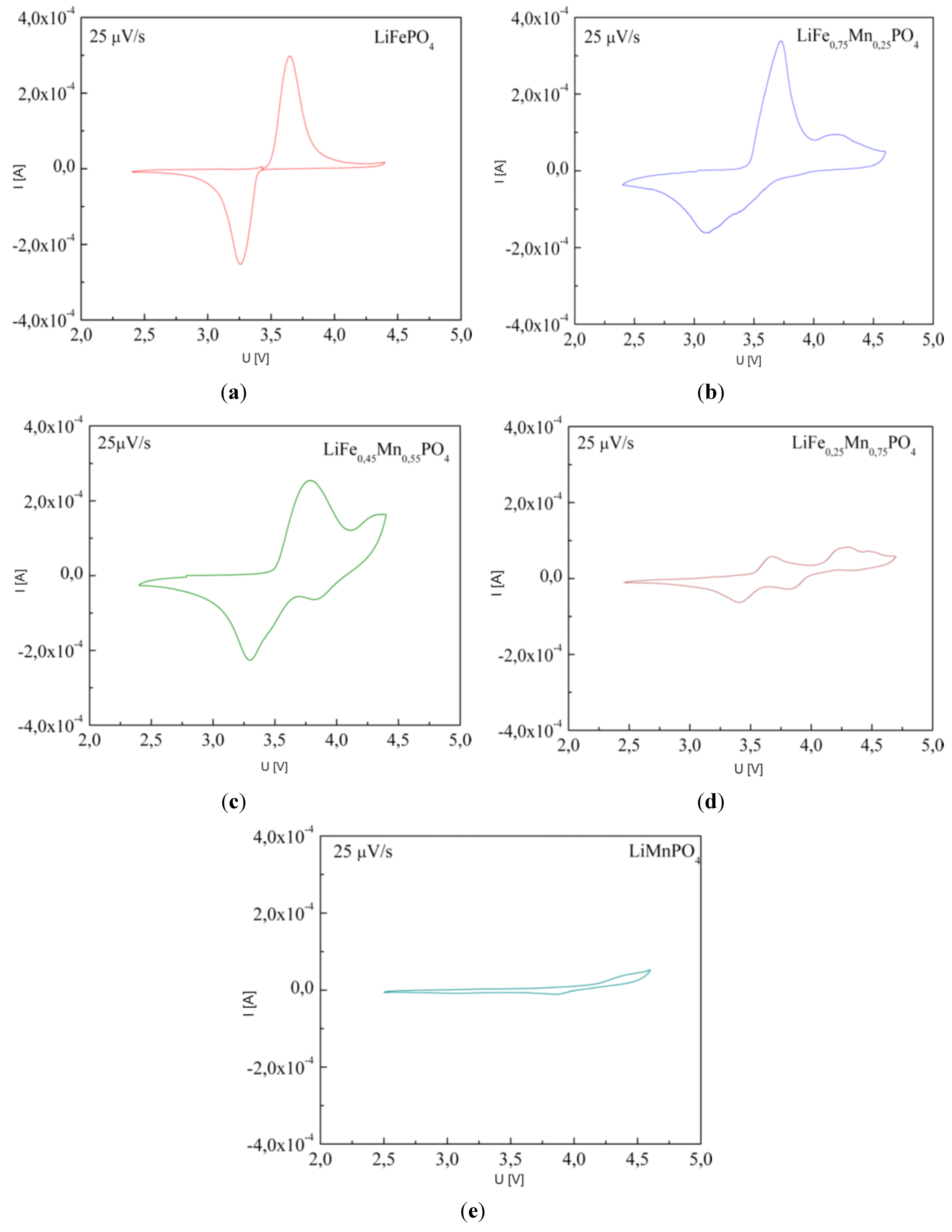

2.2.3. Electrochemical Properties

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Overview of olivines in lithium batteries for green transportation and energy storage. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Goodenough, J.B.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Electronic, optical, and magnetic properties of LiFePO4: Small magnetic polaron effects. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 3740–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.A.J.; Prieto, V.M.H.; Islam, M.S. Lithium battery materials LiMPO4 (M = Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni): Insights into defect association, transport mechanisms, and doping behavior. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 5907–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Maier, J.; Balaya, P.; Chen, D.P.; Lin, C.T. Ionic and electronic transport in single crystalline LiFePO4 grown by optical floating zone technique. Solid State Ionics 2008, 179, 1683–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, W.; Martin, S.; Vaknin, D. Lithium ion conductivity in single crystal LiFePO4. Solid State Ionics 2008, 179, 2016–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Balaya, P.; Maier, J. Anisotropy of electronic and ionic transport in LiFePO4 single crystals. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2007, 10, A13–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, J.; Ojczyk, W.; Świerczek, K.; Zając, W.; Krok, F.; Dygas, J.; Liu, R.-S. Diffusional mechanism of deintercalation in LiFe1−yMnyPO4 cathode material. Solid State Ionics 2006, 177, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.; Perry, L.K.; Ryan, D.H.; Nazar, L.F. Small polaron hopping in LixFePO4 solid solutions: Coupled lithium-ion and electron mobility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11416–11422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosini, P.P.; Lisi, M.; Zane, D.; Pasquali, M. Determination of the chemical diffusion coefficient of lithium in LiFePO4. Solid State Ionics 2002, 148, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.Y.W.; Fietzek, C.; Weydanz, W.; Donoue, K.; Inoue, T.; Kurokawa, H.; Fujitani, S. Study of LiFePO4 by cyclic voltammetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, A253–A257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.-G.; Cheng, L.; Xia, Y.-Y. Lithium-ion intercalation behavior of LiFePO4 in aqueous and nonaqueous electrolyte solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, A144–A150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.-C.; Li, L.-X.; Lai, Q.-L.; Song, X.-W.; Jiang, L.-H. Electrochemical performance of LiFePO4 thin films with different morphology and crystallinity. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 2329–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, B.; Du, H.; Xu, C.; Kang, F. The Effect of Vanadium on Physicochemical and Electrochemical Performances of LiFePO4 Cathode for Lithium Battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A26–A32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, A.K.; Nanjundaswamy, K.S.; Goodenough, J.B. Phospho-olivines as Positive-Electrode Materials for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.S.; Thomas, J.O. The source of first-cycle capacity loss in LiFePO4. J. Power Sources 2001, 498, 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Laffont, L.; Delacourt, C.; Gibot, P.; Wu, M.Y.; Kooyman, P.; Masquelier, C.; Tarascon, J.M. Study of the LiFePO4/FePO4 two-phase system by high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 5520–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Maccario, M.; Croguennec, L.; Cras, F.L.; Weill, F. Lithium deintercalation in LiFePO4 nanoparticles via a domino-cascade model. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, P.; Cogswell, D.A.; Bazant, M.Z. Suppression of phase separation in LiFePO4 Nanoparticles during battery discharge. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4890–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, A.; Cogswell, D.A.; Bazant, M.Z. Coherency strain and the kinetics of phase separation in LixFePO4. ACS Nano. 2012, 6, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazant, M.Z. Theory of Chemical Kinetics and Charge Transfer based on Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Molenda, J.; Marzec, J. Functional cathode materials for Li-ion batteries—Part I: Fundamentals. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2008, 1, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, G.-A.; Pistoia, G. Lithium Batteries Science and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rissoul, K.; Benkhouja, K.; Ramos-Barrado, J.R.; Julien, C. Electrical conductivity in lithium orthophosphates. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2003, 98, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacourt, C.; Laffont, L.; Bouchet, R.; Wurm, C.; Leriche, J.-B.; Morcrette, M.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Masquelier, C. Toward understanding of electrical limitations (electronic, ionic) in LiMPO4 (M = Fe, Mn) electrode materials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A913–A921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Driscoll, D.J.; Fisher, C.A.J.; Slater, P.R. Atomic-scale investigation of defects, dopants, and lithium transport in the LiFePO4 olivine-type battery material. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5085–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.Y.; Chiang, Y.-M. Microscale measurements of the electrical conductivity of doped LiFePO4. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2003, 6, A278–A281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.Y.; Bloking, J.T.; Chiang, Y.M. Electronically conductive phospho-olivines as lithium storage electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2002, 1, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagemaker, M.; Ellis, B.L.; Lutzenkirchen-Hecht, D.; Mulder, F.M.; Nazar, L.F. Proof of Supervalent Doping in Olivine LiFePO4. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 6313–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Jia, D.; Guo, Z.; Juan, B.S. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of nanosized carbon-coated Li1–3xLaxFePO4 composites. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2010, 14, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.R.; Vitins, G.; Owen, J.R. High-throughput studies of Li1−xMgx/2FePO4 and LiFe1−yMgyPO4 and the effect of carbon coating. J. Power Sources 2008, 179, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.Y.; Zheng, M.P.; Tong, Z.F. Effect of Ti4+ ion doping on the performance and structure of lithium iron phosphate. J. Inorg. Mater. 2006, 21, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Wang, C.S.; Kasavajjula, U. Kinetic behavior of LiFeMgPO4 cathode material for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2006, 162, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacourt, C.; Wurm, C.; Laffont, L.; Leriche, J.-B.; Masquelier, C. Electrochemical and electrical properties of Nb- and/or C-containing LiFePO4 composites. Solid State Ionics 2006, 3–4, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.Y.; Shi, S.Q.; Wang, Z.X.; Li, H.; Huang, X.J.; Chen, L.Q. The effect of Cr doping on Li ion diffusion in LiFePO4 from first principles investigations and Monte Carlo simulations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2004, 16, 2265–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, C.Y.; Wang, D.-S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Huang, X. Enhancement of electronic conductivity of LiFePO4 by Cr doping and its identification by first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 195108:1–195108:5. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, B.; Herle, P.S.; Rho, Y.H.; Nazar, L.F.; Dunlap, R.; Perry, L.K.; Ryan, D.H. Nanostructured materials for lithium-ion batteries: Surface conductivity vs. bulk ion/electron transport. Faraday Discuss. 2007, 134, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herle, P.S.; Ellis, B.; Coombs, N.; Nazar, L.F. Nano-network electronic conduction in iron and nickel olivine phosphates. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojczyk, W.; Marzec, J.; Świerczek, K.; Zając, W.; Molenda, M.; Dziembaj, R.; Molenda, J. Studies of selected synthesis procedures of the conducting LiFePO4-based composite cathode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 173, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, S.K.; Markovsky, B.; Grinblat, J.; Gofer, Y.; Haik, O.; Zinigrad, E.; Aurbach, D.; Drezen, D.; Wang, T.; Deghenghi, G.; et al. LiMnPO4 as an Advanced Cathode Material for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2009, 156, A541–A552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenstine, J.; Allen, J. Ni3+/Ni2+ redox potential in LiNiPO4. J. Power Sources 2005, 136, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabu, M.; Selvasekarapandian, S.; Reddy, M.V. Impedance studies on the 5-V cathode material, LiCoPO4. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdari, B.V.R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.S.; Zhou, Z. Fast synthesis of core-shell LiCoPO4/C nanocomposite via microwave heating and its electrochemical Li intercalation performances. Electrochem. Comm. 2009, 11, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, A.; Hosoya, M.; Chung, S.-C.; Kudo, Y.; Hinokuma, K.; Liu, K.-Y.; Nish, Y.I. Olivine-type cathodes achievements and problems. J. Power Sources 2003, 119, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Nozaki, H.; Harada, M.; Kamazawa, K.; Ikedo, Y.; Miyake, Y.; Ofer, O.; Mansson, M.; Ansaldo, E.J.; Chow, K.H.; et al. Diffusive behavior in LiMPO4 with M = Fe, Co, Ni probed by muon-spin relaxation. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 054111:1–054111:9. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, M.D.; Hoang, K.; Allen, J.L.; Gaskell, K. Hole polaron formation and migration in olivine phosphate materials. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 115106:1–115106:6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.P.; Chevrier, V.L.; Ceder, G. Comparison of small polaron migration and phase separation in olivine LiMnPO4 and LiFePO4 using hybrid density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 075112:1–075112:7. [Google Scholar]

- Kulka, A.; Milewska, A.; Zając, W.; Świerczek, K.; Hanc, E.; Molenda, J. Possibility of modification of phosphoolivine by substitution in Li sublattice. Solid State Ionics 2012, 225, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Świerczek, K.; Marzec, J.; Molenda, J. Influence of aluminium on physico-chemical properties in phosphate. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2011, 4, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, J.; Ojczyk, W.; Molenda, J. Delithiation of olivine—Structured LiFexMn1−xPO4 cathode materials. Mossbauer studies. Mater. Sci. Pol. 2006, 24, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalocogenidesa. Acta Cryst. 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Kang, K.; Maxish, T.; Ceder, G.; Morgan, D. The Li intercalation potential of LiMPO4 and LiMSiO4 olivines with M = Fe, Mn, Co, Ni. Electrochem. Commun. 2004, 132, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.; Whangbo, M.-H.; Koo, H.-J.; Rocquefelte, X.; Jobic, S.; Villesuzanne, A. Analysis of the spin exchange interactions and the ordered magnetic structures of lithium transition metal phosphates LiMPO4 (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni) with the olivine structure. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 2407–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, I.G.; Mott, N.F. Polarons in crystalline and non-crystalline materials. Adv. Phys. 1969, 18, 41–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Raveau, B. Transition Metal Oxides, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Vch: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ojczyk, W. Transport and electrochemical properties of cathode materials from the group of transition metals phosphates with olivine structure. Ph. D thesis, AGH University of Science and Technology, Cracow, Poland, 18 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, A.; Chung, S.-C. Crystal Chemistry of the Olivine-Type Li(MnyFe1−y)PO4 and (MnyFe1−y)PO4 as Possible 4 V Cathode Materials for Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A960–A967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Kudo, Y.; Liu, K.-Y. Reaction Mechanism of the Olivine-Type Lix(Mn0.6Fe0.4)PO4 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1). J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A747–A754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Kudo, Y.; Liu, K.-Y. Phase Diagram of Lix(MnyFe1−y)PO4 (0 ≤ x, y ≤ 1). J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A1153–A1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Molenda, J.; Kulka, A.; Milewska, A.; Zając, W.; Świerczek, K. Structural, Transport and Electrochemical Properties of LiFePO4 Substituted in Lithium and Iron Sublattices (Al, Zr, W, Mn, Co and Ni). Materials 2013, 6, 1656-1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6051656

Molenda J, Kulka A, Milewska A, Zając W, Świerczek K. Structural, Transport and Electrochemical Properties of LiFePO4 Substituted in Lithium and Iron Sublattices (Al, Zr, W, Mn, Co and Ni). Materials. 2013; 6(5):1656-1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6051656

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolenda, Janina, Andrzej Kulka, Anna Milewska, Wojciech Zając, and Konrad Świerczek. 2013. "Structural, Transport and Electrochemical Properties of LiFePO4 Substituted in Lithium and Iron Sublattices (Al, Zr, W, Mn, Co and Ni)" Materials 6, no. 5: 1656-1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6051656