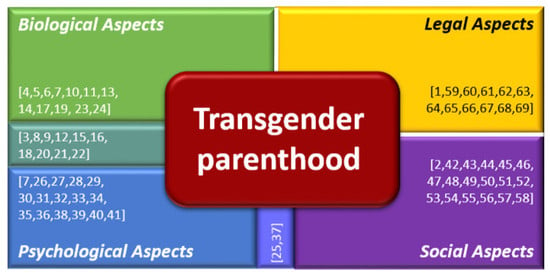

Biological, Psychological, Social, and Legal Aspects of Trans Parenthood Based on a Real Case—A Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Biological Aspects

3.2. Psychological Aspects

3.3. Social Aspects

3.4. Legal Aspects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jefatura del estado ley 14/2006, de 26 de mayo, sobre técnicas de reproducción humana asistida. In BOE núm. 126, de 27 de Mayo de 2006; p. 21. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2006-9292 (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- von Doussa, H.; Power, J.; Riggs, D. Imagining parenthood: The possibilities and experiences of parenthood among transgender people. Cult. Heal. Sex. 2015, 17, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Roo, C.; Tilleman, K.; De Sutter, P. Fertility options in transgender people. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caanen, M.R.; Soleman, R.S.; Kuijper, E.A.; Kreukels, B.; De Roo, C.; Tilleman, K.; De Sutter, P.; Van Trotsenburg, M.; Broekmans, F.; Lambalk, C. Antimüllerian hormone levels decrease in female-to-male transsexuals using testosterone as cross-sex therapy. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loverro, G.; Resta, L.; Dellino, M.; Edoardo, D.N.; Cascarano, M.A.; Loverro, M.; Mastrolia, S.A. Uterine and ovarian changes during testosterone administration in young female-to-male transsexuals. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 55, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, R.; Settineri, S.; Liotta, M.; Benvenga, S.; Trimarchi, F. Changes in hormonal and metabolic parameters in transgender subjects on cross-sex hormone therapy: A cohort study. Maturitas 2018, 107, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, A.D.; Obedin-maliver, J.; Sevelius, J.M.; Kerns, J.L. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 124, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armuand, G.; Dhejne, C.; Olofsson, J.I.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A. Transgender men’s experiences of fertility preservation: A qualitative study. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.; Andersen, C.Y.; Barri, P.N.; Brannigan, R.; Cobo, A.; Donnez, J.; Dolmans, M.M.; Evers, J.L.H.; Feki, A.; Goddijn, M.; et al. Update on fertility preservation from the Barcelona International Society for Fertility Preservation-ESHRE-ASRM 2015 expert meeting: Indications, results and future perspectives. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Dhejne, C.; Stefenson, M.; Degerblad, M.; Olofsson, J.I. Preserving eggs for men’s fertility. a pilot experience with fertility preservation for female-to-male transsexuals in sweden. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, e160–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattawanon, N.; Spencer, J.B.; Schirmer, D.A.; Tangpricha, V. Fertility preservation options in transgender people: A review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2018, 19, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ethics Committee of the American society for reproductive medicine fertility preservation and reproduction in patients facing gonadotoxic therapies: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 380–386. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ghosh, S.; Singh, S.; Chakravarty, A.; Ganesh, A.; Rajani, S.; Chakravarty, B.N. Congenital malformations among babies born following letrozole or clomiphene for infertility treatment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legro, R.S.; Brzyski, R.G.; Diamond, M.P.; Coutifaris, C.; Schlaff, W.D.; Casson, P.; Christman, G.M.; Huang, H.; Yan, Q.; Alvero, R.; et al. Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obedin-Maliver, J.; Makadon, H.J. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet. Med. 2016, 9, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.; Bockting, W.; Botzer, M.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.; DeCuypere, G.; Feldman, J.; Fraser, J.; Green, G.; Knudson, W.J.; Meyer, S.; et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 7th version; Fall, H., Ed.; World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH): East Dundee, IL, USA, 2012; 120p, ISBN 8005890036. [Google Scholar]

- Grynberg, M.; Fanchin, R.; Dubost, G.; Colau, J.C.; Brémont-Weil, C.; Frydman, R.; Ayoubi, J.M. Histology of genital tract and breast tissue after long-term testosterone administration in a female-to-male transsexual population. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 20, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; García-Velasco, J.A.; Coello, A.; Domingo, J.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J. Oocyte vitrification as an efficient option for elective fertility preservation. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, A.; Wang, L.F.; Zeymo, A.; Gomez-Lobo, V. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception 2018, 98, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James Abra, S.; Tarasoff, L.A.; Green, D.; Epstein, R.; Anderson, S.; Marvel, S.; Steele, L.S.; Ross, L.E. Trans people ’ s experiences with assisted reproduction services: A qualitative study. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, R.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Robinson, K. The transgender parent: Experiences and constructions of pregnancy and parenthood for transgender men in Australia. Int. J. Transgenderism 2018, 19, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.A.; Wojnar, D.M.; Pettinato, M. Conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender variant gestational parents: It’s how we could have a family. J. Midwifery Women Heal. 2015, 60, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández González, M.; Rodríguez Morales, G.; García-Valdecasas Campelo, J. Género y sexualidad: Consideraciones contemporáneas a partir de una reflexión en torno a la transexualidad y los estados intersexuales. Revista de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría 2010, 30, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatie, T. Labor of Love: The Story of One Man’s Extraordinary Pregnancy; Seal Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 1580053009. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.; de Bolger, A.D.P.; Dune, T.; Lykins, A.; Hawkes, G. Female-to-Male (ftm) Transgender People’s Experiences in Australia: A National Study. Springer, Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-13828-2. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, T.; Noel-Weiss, J.; West, D.; Walks, M.; Biener, M.; Kibbe, A.; Myler, E. Transmasculine individuals’ experiences with lactation, chestfeeding, and gender identity: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, L.A.; Salgado, C.J.; Villalba Alvarez, C.; Christopher, M. Transitioning transgender: Investigating the important aspects of the transition: A brief report. Int. J. Sex. Heal. 2017, 29, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.J. Voice and Communication Therapy for the Transgender or Transsexual Client: Service Delivery and Treatment Options; Graduate Independent Studies—Communication Sciences and Disorders: Evanston, IL, USA, 2016; p. 71. Available online: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/giscsd/2/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Romero, R.D.; Orozco, R.L.A.; Ybarra, S.J.L.; Gracia, R.B.I. Sintomatología depresiva en el post parto y factores psicosociales asociados. Rev. Chil. Obstet. Ginecol. 2017, 82, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitu, K. Transgender reproductive choice and fertility preservation. AMA J. Ethics 2016, 18, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sutter, P. De reproductive options for transpeople: Recommendations for revision of the WPATH’s standards of care reproductive options for transpeople: Recommendations for revision of the WPATH’s standards of care. Int. J. Transgenderism 2009, 11, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Matson, M.; Macapagal, K.; Johnson, E.K.; Rosoklija, I.; Finlayson, C.; Fisher, C.B.; Mustanski, B. Attitudes toward fertility and reproductive health among transgender and gender-nonconforming adolescents. Proc. IEEE 2018, 63, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornello, S.L.; Bos, H. Parenting intentions among transgender individuals. LGBT Heal. 2017, 4, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousineau, T.M.; Domar, A.D. Psychological impact of infertility. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulens Ramos, I. Análisis de los cuidados de enfermería ante las respuestas humanas en el Aborto Espontáneo. Rev. Habanera Ciencias Médicas 2009, 8, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bordón Guerra, R.; Averasturi, L.M.G. Protocolo de Intervención Psicológica en la Transexualidad; Hojas Informativas de las Psicólogas de Las Palmas; Colegio Oficial de Psicólogos: Las Palmas, Spain, 2001; pp. 1576–2157. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffkling, A.; Obedin-maliver, J.; Sevelius, J. From erasure to opportunity: A qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, S. Susana entrevistó a un Transexual Embarazado. Infobae 2013. Available online: https://www.infobae.com/2013/08/26/1504493-susana-entrevisto-un-transexual-embarazado (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Macdonald, T. Lactancia: Apoyando a los Hombres Transexuales. Docplayer. La liga de la leche Euskadi. 2018. Available online: https://docplayer.es/69614878-Lactancia-apoyando-a-hombres-transexuales.html (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Milk Junkies Breastfeeding/Chestfeeding and Gradual Weaning: A Snapshot in Time. 2018. Available online: http://www.milkjunkies.net/ (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Platero Méndez, L.; Ortega Arjonilla, E. Investigación Sociológica Sobre las Personas Transexuales y sus Experiencias Familiares; Transexualia: Madrid, Spain, 2017; 196p, ISBN 9788461785889. Available online: http://feministas.org/IMG/pdf/2017investigacionpersonastransexperienciasfamiliares.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Marx, R.; Katz, M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons. The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. J. Homosex. 2006, 51, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, E.L.; Wilchins, R.A.; Priesing, D.; Malouf, D. Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J. Homosex. 2002, 42, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotzer, R.L. Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenagy, G.P. Transgender health: Findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health Soc. Work 2005, 30, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuttbrock, L.; Hwahng, S.; Bockting, W.; Rosenblum, A.; Mason, M.; MacRi, M.; Becker, J. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. J. Sex Res. 2010, 47, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehnle, K.; Sullivan, A. Patterns of anti-gay violence: An analysis of incident characteristics and victim reporting. J. Interpers. Violence 2001, 16, 928–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R.; Hammond, R.; Travers, R.; Kaay, M.; Hohenadel, K.M.; Boyce, M. “I don’t think this is theoretical; This is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2009, 20, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockting, W.O.; Miner, M.H.; Swinburne Romine, R.E.; Hamilton, A.; Coleman, E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.; Robinson, B.; Benner, A.; Scheltema, K. Patient satisfaction with transgender health services. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2004, 30, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, R.; Watkins, R.; Zappia, T.; Nicol, P.; Shields, L. Nursing and medical students’ attitude, knowledge and beliefs regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender parents seeking health care for their children. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunner, B.P.; Grace, P.J. The ethical nursing care of transgender patients. Am. J. Nurs. 2012, 112, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardacker, C.T.; Rubinstein, B.; Hotton, A.; Houlberg, M. Adding silver to the rainbow: The development of the nurses’ health education about LGBT elders (HEALE) cultural competency curriculum. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, A.; MacDonnell, J.A. “That would have been beneficial”: LGBTQ education for home-care service providers. Heal. Soc. Care Community 2015, 23, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyssel, J.; Koehler, A.; Dekker, A.; Sehner, S.; Nieder, T.O. Needs and concerns of transgender individuals regarding interdisciplinary transgender healthcare: A non-clinical online survey. PLoS ONE 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spidsberg, B.D. Vulnerable and strong—Lesbian women encountering maternity care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuss, D. Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 0091-8369. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J.K.; Kuvalanka, K.A.; Catalpa, J.M.; Toomey, R.B. Transfamily theory: How the presence of trans* family members informs gender development in families. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Access to fertility services by transgender persons: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Lesbian Rights. State by State Guide to Laws That Prohibit Discrimination Against Transgender People; National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR): Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.nclrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/StateLawsThatProhibitDiscriminationAgainstTransPeople.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- InfoLEG. Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Públicas—Argentina. Argentina Ley 26.862 Reproducción Médicamente Asistida 2013. Available online: http://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/215000-219999/216700/norma.htm (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- TGEU. Map TVT. 2018. Available online: https://transrespect.org/en/map/un-ga/ (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- Palazzani, L. Gender in Philosophy and Law. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012. Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/10164 (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Onufer Corrêa, S.; Muntarbhorn, V. The Yogyakarta Principles. 2007, p. 38. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/principles_en.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Cabral Grinspan, M.; Carpenter, M.; Ehrt, J.; Kara, S.; Narrain, A.; Patel, P.; Sidoti, C.; Tabengwa, M. The Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10. 2017, p. 27. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/A5_yogyakartaWEB-2.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Human Rights Watch World Report 2008. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/01/30/world-report-2008/events-2007 (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- ILGA-Europe. Country Ranking|Rainbow Europe. 2017. Available online: https://rainbow-europe.org/country-ranking (accessed on 16 December 2018).

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley 3/2007, de 15 de marzo, reguladora de la rectificacion registral de la mención relativa al sexo de las personas. BOE núm. 65, de 16 de Marzo de 2007. pp. 11251–11253. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2007/03/16/pdfs/A11251-11253.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2018).

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Real Decreto 1030/2006, de 15 de septiembre, por el que se establece la cartera de servicios comunes del Sistema Nacional de Salud y el procedimiento para su actualización. BOE núm. 222 de 16 de Septiembre de 2006. p. 78. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2006/BOE-A-2006-16212-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de-Castro-Peraza, M.-E.; García-Acosta, J.M.; Delgado-Rodriguez, N.; Sosa-Alvarez, M.I.; Llabrés-Solé, R.; Cardona-Llabrés, C.; Lorenzo-Rocha, N.D. Biological, Psychological, Social, and Legal Aspects of Trans Parenthood Based on a Real Case—A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060925

de-Castro-Peraza M-E, García-Acosta JM, Delgado-Rodriguez N, Sosa-Alvarez MI, Llabrés-Solé R, Cardona-Llabrés C, Lorenzo-Rocha ND. Biological, Psychological, Social, and Legal Aspects of Trans Parenthood Based on a Real Case—A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(6):925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060925

Chicago/Turabian Stylede-Castro-Peraza, Maria-Elisa, Jesús Manuel García-Acosta, Naira Delgado-Rodriguez, Maria Inmaculada Sosa-Alvarez, Rosa Llabrés-Solé, Carla Cardona-Llabrés, and Nieves Doria Lorenzo-Rocha. 2019. "Biological, Psychological, Social, and Legal Aspects of Trans Parenthood Based on a Real Case—A Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 6: 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060925