Impact of National Smoke-Free Legislation on Educational Disparities in Smoke-Free Homes: Findings from the SIDRIAT Longitudinal Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

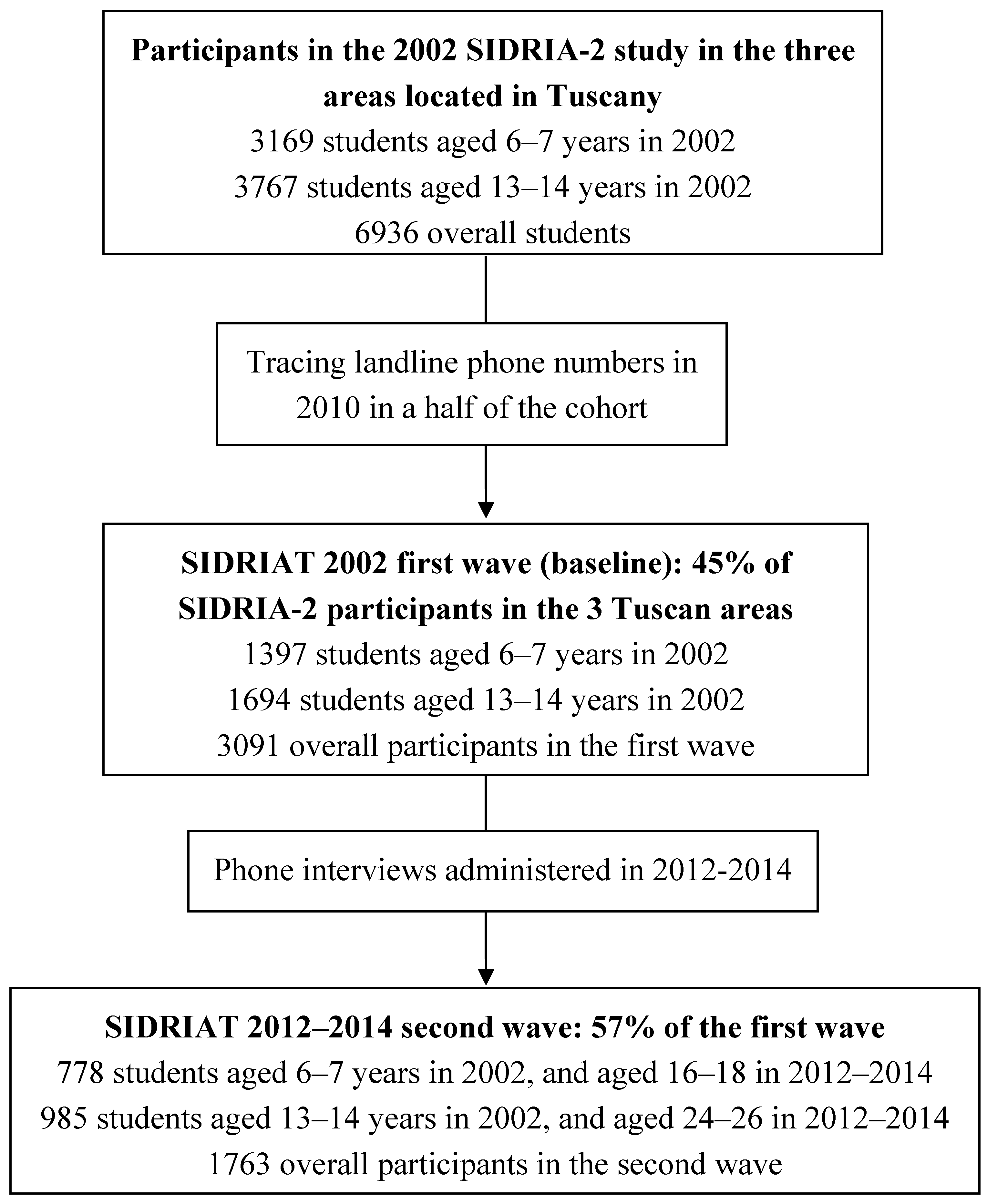

2.1. First Wave of the Survey (Baseline Survey)

2.2. Second Wave (Follow-Up Survey)

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

| Non-Smoking Parents (N = 1027*) | ≥1 Smoking Parent (N = 736*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSB (N = 905) n (%) | No HSB (N = 101) n (%) | HSB (N = 161) n (%) | No HSB (N = 570) n (%) | |

| Gender, Boys | 460 (50.8) | 43 (42.6) | 66 (41.0) | 301 (52.8) |

| Cohort, Children | 443 (49.0) | 12 (11.9) | 96 (59.6) | 218 (38.3) |

| Smoking Status, Current Smoker | 4 (0.4) | 13 (12.9) | 2 (1.2) | 21 (3.7) |

| Parents’ Educational Level, ≥1 Graduate Parent | 224 (24.8) | 17 (16.8) | 50 (31.1) | 72 (12.6) |

3.2. Trends in HSB

3.3. Socioeconomic Status and Presence, Adoption and Removal of A HSB

| Baseline | |||

| Absence of HSB N (%) | Presence of HSB N (%) | Presence vs. Absence of HSB PR (95%CI) § | |

| No Graduate Parents | 525 (78.2) | 745 (69.9) | 1* |

| At Least One Graduate Parent ** | 89 (13.3) | 274 (25.7) | 1.34 (1.15–1.57) |

| Follow-Up | |||

| Absence of HSB N (%) | Presence of HSB N (%) | Presence vs. Absence of HSB PR (95%CI) §§ | |

| No Graduate Parents | 298 (72.2) | 993 (73.7) | 1* |

| At Least One Graduate Parent ** | 83 (20.1) | 283 (21.0) | 0.98 (0.80–1.19) |

| Best Homes N (%) | Improving Homes N (%) | Worsening Homes N (%) | Worst Homes N (%) | Best + Worsening + Worst Homes N (%) | |

| At Least One Graduate Parent | 229 (25.1) | 50 (12.1) | 44 (28.8) | 39 (15.1) | 324 (23.6) |

| No Graduate Parents | 645 (70.8) | 327 (79.4) | 99 (64.7) | 198 (76.4) | 976 (71.0) |

| Improving vs. Best Homes, PR (95% CI) § | Worsening vs. Best Homes, PR (95% CI) § | Worst vs. Best Homes PR (95% CI) § | Improving vs. All Other Homes PR (95% CI) § | ||

| At Least One Graduate Parent | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | |

| No Graduate Parents | 1.49 (1.19–1.88) | 0.88 (0.64–1.23) | 1.43 (1.14–1.81) | 1.48 (1.15–1.92) | |

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General; Office on Smoking and Health, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies. In Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2009; pp. 9–58. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; Office of the Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Oberg, M.; Jaakkola, M.S.; Woodward, A.; Peruga, A.; Prüss-Ustün, A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: A retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011, 377, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention On Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241591013.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Guidelines for Implementation. 2013. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80510/1/9789241505185_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic. In Implementing Smoke-Free Environments; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2009/mpower_report_2009_executive_summary_EN_11b.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- WHO Report on the global tobacco epidemic. In Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85380/1/9789241505871_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 16 January 2015).

- Minardi, V.; Gorini, G.; Carreras, G.; Masocco, M.; Ferrante, G.; Possenti, V.; Quarchioni, E.; Spizzichino, L.; Galeone, D.; Vasselli, S.; Salmaso, S. Compliance with the smoking ban in Italy 8 years after its application. Int. J. Public Health 2014, 59, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorini, G.; Moshammer, H.; Sbrogiò, L.; Gasparrini, A.; Nebot, M.; Neuberger, M.; Tamang, E.; Lopez, M.J.; Galeone, D.; Serrahima, D. Second-hand smoke Exposure in Italian and Austrian Hospitality premises before and after 2 years from the introduction of the Italian smoking ban. Indoor Air 2008, 18, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borland, R.; Yong, H.H.; Cummings, K.M.; Hyland, A.; Anderson, S.; Fong, G.T. Determinants and consequences of smoke-free homes: findings from the international tobacco control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob. Control 2006, 15, iii42–iii50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferketich, A.K.; Lugo, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Fernandez, E.; Boffetta, P.; Clancy, L.; Gallus, S. Relation between national-level tobacco control policies and individual-level voluntary home smoking bans in Europe. Tob. Control 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Blanch, C.; Fu, M.; Gallus, S.; La Vecchia, C.; Fernández, E. Do smoke-free policies in work and public places increase smoking in private venues? Tob. Control 2014, 23, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, A.L.; White, M.M.; Pierce, J.P.; Messer, K. Home smoking bans among US households with children and smokers: opportunities for intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.A.; Hyland, A.J.; Borland, R.; McNeill, A.; Cummings, K.M. Socioeconomic variation in the prevalence, introduction, retention, and removal of smoke-free policies among smokers: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huisman, M.; Kunst, A.E.; Mackenbach, J.P. Educational inequalities in smoking among men and women aged 16 years and older in 11 European countries. Tob. Control 2005, 14, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, N.; Aït-Khaled, N.; Beasley, R.; Mallol, J.; Keil, U.; Mitchell, E.; Robertson, C.; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: Phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax 2007, 62, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galassi, C.; De Sario, M.; Biggeri, A.; Bisanti, L.; Chellini, E.; Ciccone, G.; Petronio, M.G.; Piffer, S.; Sestini, P.; Rusconi, F.; Viegi, G.; Forastiere, F. Changes in prevalence of asthma and allergies among children and adolescents in Italy: 1994–2002. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galassi, C.; Forastiere, F.; Biggeri, A.; Gabellini, C.; De Sario, M.; Ciccone, G.; Biocca, M.; Bisanti, L.; Gruppo Collaborativo SIDRIA-2. SIDRIA second phase: Objectives, study design and methods. Epidemiol. Prev. 2005, 29 (2 Suppl), 9–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sestito, L.A.; Sica, L.S. Identity formation of Italian emerging adults living with parents: A narrative study. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1435–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.R.; Deddens, J.A. A comparison of two methods for estimating prevalence ratios. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, G. A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 159, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Warehouse of statistics currently produced by ISTAT. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/ (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Mons, U.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Allwright, S.; Guignard, R.; van den Putte, B.; Willemsen, M.C. Impact of national smoke-free legislation on home smoking bans: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project Europe Surveys. Tob. Control 2012, 22, e2–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolte, G.; Fromme, H. Socioeconomic determinants of children’s environmental tobacco smoke exposure and family’s home smoking policy. Eur. J. Public Health 2008, 19, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.L.; Gamst, A.C.; Cummins, S.E.; Wolfson, T.; Zhu, S.H. Comparison of smoking cessation between education groups: findings from 2 US National Surveys over 2 decades. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gorini, G.; Carreras, G.; Cortini, B.; Verdi, S.; Petronio, M.G.; Sestini, P.; Chellini, E. Impact of National Smoke-Free Legislation on Educational Disparities in Smoke-Free Homes: Findings from the SIDRIAT Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 8705-8716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120808705

Gorini G, Carreras G, Cortini B, Verdi S, Petronio MG, Sestini P, Chellini E. Impact of National Smoke-Free Legislation on Educational Disparities in Smoke-Free Homes: Findings from the SIDRIAT Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(8):8705-8716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120808705

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorini, Giuseppe, Giulia Carreras, Barbara Cortini, Simona Verdi, Maria Grazia Petronio, Piersante Sestini, and Elisabetta Chellini. 2015. "Impact of National Smoke-Free Legislation on Educational Disparities in Smoke-Free Homes: Findings from the SIDRIAT Longitudinal Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 8: 8705-8716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120808705

APA StyleGorini, G., Carreras, G., Cortini, B., Verdi, S., Petronio, M. G., Sestini, P., & Chellini, E. (2015). Impact of National Smoke-Free Legislation on Educational Disparities in Smoke-Free Homes: Findings from the SIDRIAT Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(8), 8705-8716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120808705