Impact of an Electronic Cigarette on Smoking Reduction and Cessation in Schizophrenic Smokers: A Prospective 12-Month Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design and Baseline Measures

2.3. Study Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Participant Characteristics

| Parameter | Mean (±SD) * | |

|---|---|---|

| * Non-parametric data expressed as median (IQR). Abbreviations: SD: Standard Deviation; M: Male; F: Female; FTND: Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence; eCO: exhaled carbon monoxide; IQR: interquartile range; SAPS: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms. | ||

| Subjects eligible for inclusion (n = 14) | Age | 44.6 (±12.5) |

| Sex | 6M; 8F | |

| Pack Years | 28.8 (±12.9) | |

| FTND | 7 (5, 10) * | |

| SAPS | 15 (9.5, 22) * | |

| SANS | 44 (26.75, 53.5) * | |

| Cigarettes/day | 30 (20, 35) * | |

| eCO | 29 (23.5, 35.2) * | |

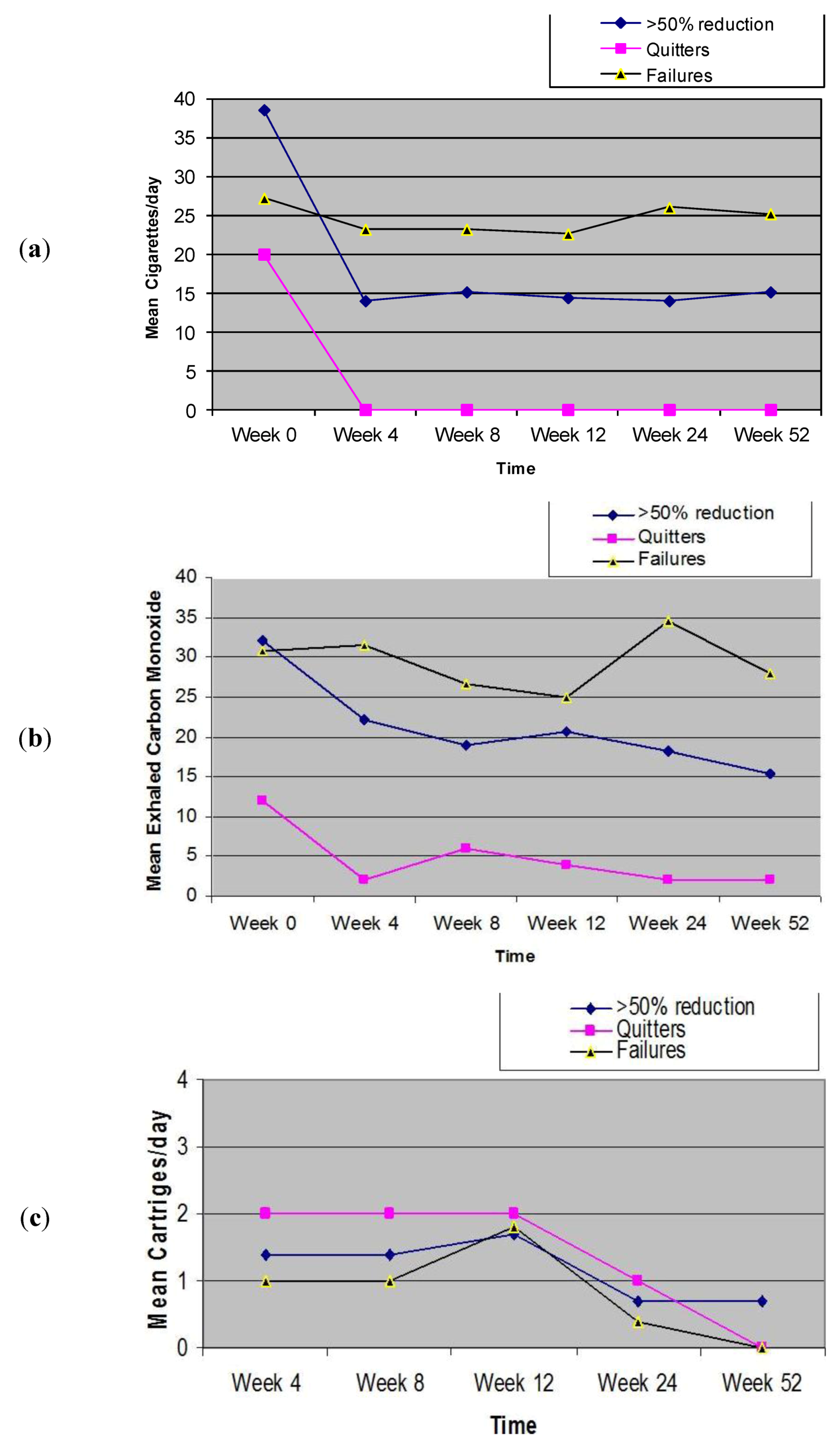

3.2. Outcome Measures

3.3. Product Use

| Parameter | AT BASELINE | AT 52-Weeks | p value ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post E-Cigarette | |||

| Sustained 50% (excluding quitters) reduction in cigarette smoking (n = 7) | |||

| Age | 42.4 (±8.3) † | ||

| Sex | 3M; 4F | ||

| Pack Years | 34.7 (±12.1) † | ||

| Cigarettes/day | 30 (30, 60) * | 15 (10, 20) * | 0.018 |

| eCO | 32 (22, 39) * | 17 (11, 20) * | 0.028 |

| SAPS | 15 (12, 23) * | 12 (10, 25) * | 0.147 |

| SANS | 51 (41, 63) * | 45 (40, 48) * | 0.351 |

| Sustained 100% (quitters) reduction in cigarette smoking (n = 2) | |||

| Age | 51(±7.1) † | ||

| Sex | 1M; 1F | ||

| Pack Years | 20.25 (±0.0) † | ||

| Cigarettes/day | 20 (15, 15) * | 0 (0, 0) * | 0.157 |

| eCO | 24 (15.7, 20. 3) * | 2 (1.5, 1.5) * | 0.180 |

| SAPS | 13 (3, 16.5) * | 14 (4.5, 16.5) * | 0.317 |

| SANS | 27.5 (7.5, 33.8) * | 26.5 (7.5, 32.2) * | 0.317 |

| Sustained >50% (including quitters) reduction in cigarette smoking (n = 9) | |||

| Age | 44.3 (±8.5) † | ||

| Sex | 4M; 5F | ||

| Pack Years | 31.5 (±12.2) † | ||

| Cigarettes/day | 30 (25, 45) * | 12 (4.5, 17.5) * | 0.007 |

| eCO | 22 (15, 32) * | 12 (6, 15.5) * | 0.021 |

| SAPS | 15 (10, 22.5) * | 12 (10, 22.5) * | 0.203 |

| SANS | 48 (35.5, 62) * | 45 (39, 27.5) * | 0.260 |

| Smoking Failure (<50% smoking reduction) (n = 5) | |||

| Age | 40.6 (±17.7) † | ||

| Sex | 2M; 3F | ||

| Pack Years | 23.9 (±14.3) † | ||

| Cigarettes/day | 21(17.5, 40) * | 21 (17.5, 35) * | 0.317 |

| eCO | 28 (25, 38) * | 29 (20, 35.5) * | 0.345 |

| SAPS | 12 (9, 18.5) * | 11 (9, 17) * | 0.581 |

| SANS | 30 (13.5, 48.5) * | 32 (14.5, 45) * | 0.684 |

3.4. Adverse Events

| Adverse Event | Study Visits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-week n/n (%) | 8-week n/n (%) | 12-week n/n (%) | 24-week n/n (%) | 52-week n/n (%) | |

| Throat irritation * | 1/14 (7.2%) | 2/14 (14.4%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Mouth Irritation * | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Sore Throat | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Dry cough | 4/14 (28.6%) | 4/14 (28.6%) | 1/14 (7.2%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Dry mouth | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Mouth ulcers | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (2.9%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Dizziness § | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0) | 0/14 (10%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Headache | 2/14 (14.4%) | 1/14 (7.2%) | 1/14 (7.2%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Nausea | 2/14 (14.4%) | 0/14 (0%) | 1/14 (7.2%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Depression | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Anxiety | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Insomnia | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Irritability | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Hunger | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| Constipation | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/14 (0%) |

| AEs | 4-week | 8-week | 12-week | 24-week | 52-week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry cough | failures (n 2) | failures (n 2) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) |

| reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | |

| abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | |

| Headache | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) |

| reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | |

| abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | |

| Nausea | failures (n 1) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) |

| reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | |

| abstainers (n 1) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | |

| Throat irritation | failures (n 0) | failures (n 1) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) | failures (n 0) |

| reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 1) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | reducers (n 0) | |

| abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) | abstainers (n 0) |

3.5. Positive and Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia

3.6. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- de Leon, J.; Diaz, F.J. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 76, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, N.L.; Grant, J.S. Smoke, smoke, smoke that cigarette. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2006, 42, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, A.H. Cigarette smoking: Implications for psychiatric illness. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 546–553. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.; McCreadie, R.G. Smoking habits, current symptoms, and premorbid characteristics of schizophrenic patients in Nithsdale, Scotlad. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar]

- Addington, J. Group treatment for smoking cessation among persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Services 1998, 49, 925–928. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Inskip, H.; Barraclough, B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Brit. J. Psychiat. 2000, 177, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; Office on Smoking and Health. In The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation; United States Public Health Service. Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1990.

- Lightwood, J.M.; Glantz, S.A. Short-term economic and health benefits of smoking cessation: Myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation 1997, 96, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, G.; Caponnetto, P.; Polosa, R. Therapeutic advances in the treatment of nicotine addiction: Present and future. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2010, 1, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.P.; Ziedonis, D.M.; Feingold, A.; Pepper, W.T.; Satterburg, C.A.; Winkel, J.; Rounsaville, B.J.; Kosten, T.R. Nicotine transdermal patch and atypical antipsychotic medications for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Amer. J. Psychiat. 2006, 157, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Aubin, H.J.; Rollema, H.; Svensson, T.H.; Winterer, G. Smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disease: A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polosa, R.; Benowitz, N.L. Treatment of nicotine addiction: Present therapeutic options and pipeline developments. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, L. A Non-Smokable Electronic Spray Cigarette. Canada Patent CA 2518174, 6 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zezima, K. Cigarettes without smoke or regulation. New York Times 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, J.F. Electronic cigarettes: A survey of users. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansickel, A.R.; Cobb, C.O.; Weaver, M.F.; Eissenberg, T.E. A clinical laboratory model for evaluating the acute effects of electronic “cigarettes”: Nicotine delivery profile and cardiovascular and subjective effects. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polosa, R.; Caponnetto, P.; Morjaria, J.B.; Papale, G.; Campagna, D.; Russo, C. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e-Cigarette) on smoking reduction and cessation: A prospective 6-month pilot study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponnetto, P. The Efficacy and Safety of an Electronic Cigarette (ECLAT) Study: A Prospective 12 Month Randomized Control Design Study. In XIV Annual Meeting of the SRNT Europe, Helsinki, Finland, 30 August–2 September 2012.

- World Health Organisation, ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders—Research Version (SCID-1); Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom, K.O.; Schneider, N.G. Measuring nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J. Behav. Med. 1989, 12, 159–182. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, N.C. The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 1983.

- Andreasen, N.C. The Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 1984.

- Classificazione ed Etichettatura Delle Miscele Contenute Nelle Cartucce Denominate “Categoria”. 2010. Available online: www.liaf-onlus.org/public/allegati/categoria1b.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2011).

- Bolliger, C.T.; Zellweger, J.P.; Danielsson, T.; van Biljon, X.; Robidou, A.; Westin, A.; Perruchoud, A.P.; Sawe, U. Smoking reduction with oral nicotine inhalers: Double blind, randomised clinical trial of efficacy and safety. BMJ 2000, 321, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 17.0, SPSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008.

- Dalack, G.W.; Becks, L.; Hill, E.; Pomerleau, O.F.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Nicotine withdrawal and psychiatric symptoms in cigarette smokers with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999, 21, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evins, A.E.; Mays, V.K.; Rigotti, N.A.; Tisdale, T.; Cather, C.; Goff, D.C. A pilot trial of bupropion added to cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2001, 3, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalack, G.W.; Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Acute feasibility and safety of a smoking reduction strategy for smokers with schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob. Res. 1999, 1, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, L.E.; Hoffer, L.D.; Wiser, A.; Freedman, R. Normalization of auditory physiology by cigarette smoking in schizophrenic patients. Amer. J. Psychiat. 1993, 150, 1856–1861. [Google Scholar]

- George, T.P.; Vessicchio, J.C.; Termine, A.; Sahady, D.M.; Head, C.A.; Pepper, W.T.; Kosten, T.R.; Wexler, B.E. Effects of smoking abstinence on visuospatial working memory function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 26, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.D.; Wilson, W.; Rose, J.E.; McEvoy, J. Nicotine-haloperidol interactions and cognitive performance in schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996, 15, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decina, P.; Caracci, G.; Sandik, R.; Berman, W.; Mukherjee, S.; Scapicchio, P. Cigarette smoking and neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism. Biol. Psychiat. 1990, 28, 502–508. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, J.P.; Freudenreich, O.; Levin, E.D.; Rose, J.E. Haloperidol increases smoking in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 1995, 119, 124–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, J. Smoking and vulnerability for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1996, 22, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassen, H.H.; Bridler, R.; Hagele, S.; Hergersberg, M.; Mehmann, B.; Schinzel, A.; Weisbrod, M.; Scharfetter, C. Schizophrenia and smoking: Evidence for a common neurobiological basis? Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 96, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.M.; O’Neill, J.E.; Petty, F.; Garver, D.; Young, D.; Freedman, R. Nicotinic receptor desensitization and sensory gating deficits in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiat. 1998, 44, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponnetto, P.; Cibella, F.; Mancuso, S.; Campagna, D.; Arcidiacono, G.; Polosa, R. Effect of a nicotine free inhalator as part of a smoking cessation program. ERJ 2011, 38, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Wieslander, G.; Norback, D.; Lindgren, T. Experimental exposure to propylene glycol mist in aviation emergency training: Acute ocular and respiratory effects. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 58, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varughese, S.; Teschke, K.; Brauer, M.; Chow, Y.; van Netten, C.; Kennedy, S.M. Effects of theatrical smokes and fogs on respiratory health in the entertainment industry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005, 47, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerstrom, K.O.; Hughes, J.R.; Rasmussen, T.; Callas, P.W. Randomised trial investigating effect of a novel nicotine delivery device (Eclipse) and a nicotine oral inhaler on smoking behaviour, nicotine and carbon monoxide exposure, and motivation to quit. Tob. Control 2000, 9, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, A. Harm reduction. BMJ 2004, 328, 885–887. [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger, C.T.; Zellweger, J.P.; Danielsson, T.; van Biljon, X.; Robidou, A.; Westin, A.; Perruchoud, A.P.; Sawe, U. Influence of long-term smoking reduction on health risk markers and quality of life. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002, 4, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsukami, D.K.; Kotlyar, M.; Allen, S.; Jensen, J.; Li, S.; Le, C.; Murphy, S. Effects of cigarette reduction on cardiovascular risk factors and subjective measures. Chest 2005, 128, 2528–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godtfredsen, N.S.; Prescott, E.; Osler, M. Effect of smoking reduction on lung cancer risk. JAMA 2005, 294, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.R.; Carpenter, M.J. The feasibility of smoking reduction: An update. Addiction 2005, 100, 1074–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennike, P.; Danielsson, T.; Landfeldt, B.; Westin, A.; Tonnesen, P. Smoking reduction promotes smoking cessation: Results from a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nicotine gumwith 2-year follow-up. Addiction 2003, 98, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennard, S.I.; Glover, E.D.; Leischow, S.; Daughton, D.M.; Glover, P.N.; Muramoto, M.; Franzon, M.; Danielsson, T.; Landfeldt, B.; Westin, A. Efficacy of the nicotine inhaler in smoking reduction: A double-blind, randomized trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006, 8, 555–654. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, N.; Bullen, C.; McRobbie, H. Reduced-nicotine content cigarettes: Is there potential to aid smoking cessation? Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009, 11, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Anthenelli, R.M.; Morris, C.D.; Treadow, J.; Thompson, J.R.; Yunis, C.; George, T.P. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J. Clin. Psychiat. 2012, 73, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Caponnetto, P.; Auditore, R.; Russo, C.; Cappello, G.C.; Polosa, R. Impact of an Electronic Cigarette on Smoking Reduction and Cessation in Schizophrenic Smokers: A Prospective 12-Month Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 446-461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10020446

Caponnetto P, Auditore R, Russo C, Cappello GC, Polosa R. Impact of an Electronic Cigarette on Smoking Reduction and Cessation in Schizophrenic Smokers: A Prospective 12-Month Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(2):446-461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10020446

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaponnetto, Pasquale, Roberta Auditore, Cristina Russo, Giorgio Carlo Cappello, and Riccardo Polosa. 2013. "Impact of an Electronic Cigarette on Smoking Reduction and Cessation in Schizophrenic Smokers: A Prospective 12-Month Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 2: 446-461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10020446

APA StyleCaponnetto, P., Auditore, R., Russo, C., Cappello, G. C., & Polosa, R. (2013). Impact of an Electronic Cigarette on Smoking Reduction and Cessation in Schizophrenic Smokers: A Prospective 12-Month Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(2), 446-461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10020446