Anticancer Effects of Different Seaweeds on Human Colon and Breast Cancers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Seaweed | Nature | Colorectal Cancer | Breast Cancer | Other Cancers | Therapeutic Element | IC50 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucus sp. | Brown algae | + | + | - | Fucoidan | 5–20 μg/mL | Kim et al. 2010 [2] |

| Stypopodium sp. | Brown algae | + | - | + | Meroditerpenoids | 12.2 μM and 14 μM | Pereira et al. 2011 [7] |

| Sargassum muticum | Brown algae | - | + | - | Polyphenol | 0.2 μg/mL | Namvar et al. 2013 [9] |

| Ulva fasciata | Green algae | - | - | + | Flavoids | 200 μg/mL | Ruy et al. 2013 [11] |

| Laminaria sp. | Brown algae | + | - | - | Laminarin | Park et al. 2012; 2013 [12,13] | |

| Laurencia sp. | Red algae | + | - | - | Dactylone | 45.4 µmol/L | Federov et al. 2007 [14] |

| Ishige okamurae Phoma herbarum | Red algae | - | - | + | Ethanol extracts | Kim et al. 2009 [15] | |

| Lithothamnion sp. | Red algae | + | - | - | Cellfood * | Aslam et al. 2009 [16] | |

| Porphyra dentata | Red algae | - | + | - | Sterol fraction | 48.3 µg/mL | Kazlowska et al. 2013 [17] |

| Cymopolia barbata | Green algae | - | + | - | CYP1 inhibitors | 19.82 μM and 55.65 μM | Badal et al. 2013 [18] |

| Lophocladia sp. | Red algae | - | + | - | Lophocladines | 3.1 μM and 64.6 µM | Gross 2006 [19] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum | Brown algae | - | + | - | Fucoidan | Pavia et al. 1996 [20] | |

| Gracilaria termistipitata | Red algae | - | - | + | Methanol extracts | Ji et al. 2012 [21] | |

| Enteromorpha intestinalis Rhizoclonium riparium | Green algae | - | - | + | Methanol extracts | 309.05 µg/mL and 506.08 µg/m | Paul et al. 2013 [22] |

| Aspergillus sp. | Brown algae | - | - | + | Gliotoxin | Nguyen et al. 2014 [23] | |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Brown algae | Fucoidan | Yang et al. 2013 [24] |

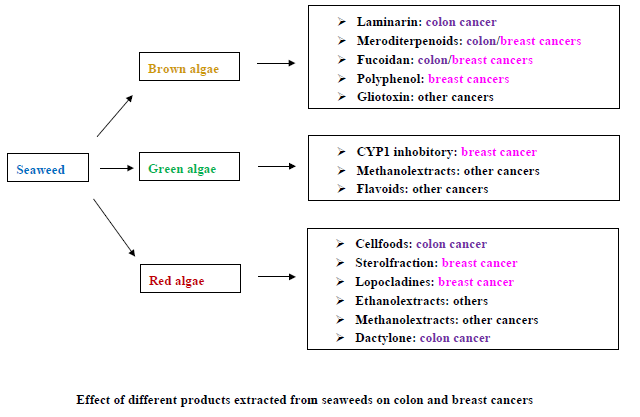

2. Seaweed and Colorectal Cancer

| Therapeutic Compounds (Seaweed) | Action Site | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Arrest | Mitochondrial Membrane | Caspases or Cyclins | GFR | P53 | Pro- or Anti-Apoptotic Proteins | ||

| Fucoidan (Fucus sp.) | + | + | + | + | + | Kim et al. 2010 [2]/Xue et al. 2012 [31] | |

| Laminarin (Laminaria sp.) | + | + | + | + | + | Park et al. 2012; 2013 [12,13] | |

| Dactylone (Laurencia sp.) | + | - | + | - | + | Fedorov et al. 2007 [14] | |

| Steorol fraction (Porphyra dentata) | + | - | - | - | - | - | Kazlowska et al. 2013 [17] |

| Methanol extracts (Sargassum muticum) | + | - | - | - | - | - | Paul et al. 2013 [22] |

| Colorectal Cancer | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Seaweeds | Therapeutic compounds and their properties | |

| Laminaria digitata | Laminarin from Laminaria digitata induced apoptosis in HT-29 colon cancer cells; affected insulin-like growth factor (IGF-IR); decreased mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and ERK phosphorylation; decreased IGF-IR-dependent proliferation | Park et al. 2012; 2013 [12,13] |

| Lithothamnion calcareum (Pallas), also known as Phymatolithon calcareum (Pallas) | Multi-mineral extract from Lithothamnion calcareum can protect mice on a high-fat diet against adenomatous polyp formation in the colon | |

| Cymopolia barbata | Prenylated bromohydroquinones (PBQs) isolated from Cymopolia barbata show selectivity and potency against HT-29 cells and inhibit CYP1 enzyme activity, which may be a lead in chemoprevention | |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Fucoxanthin from Undaria pinnatifida attenuated rifampin-induced CYP3A4, MDR1 mRNA and CYP3A4 protein expression | |

3. Seaweed and Breast Cancer

| Seaweed | Therapeutic Compounds and Their Properties | References |

|---|---|---|

| Sargassum muticum | Sargassum muticum methanol extract (SMME) Induced apoptosis of MCF-7 cells; showed anti-angiogenic activity in the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay; antioxidant effects | Namvar et al. 2013 [9] |

| Fucus vesiculosus | Fucoidan (sulfated polysaccharide derived from brown algae) Decreased the viable number of 4T1 cells; induced apoptosis; down-regulated VEGF expression In colon cancer reduced in viable cell numbers and induced apoptosis of human lung carcinoma A549 cells as well as colon cancer HT-29 and HCT116 cells | Xue et al. 2012 [31]/ Kim et al. 2010 [2] |

| Porphyra dentata | Sterol fraction (containing cholesterol, β-sitosterol, and campesterol) from Porphyra dentata Significantly inhibited cell growth in vitro and induced apoptosis in 4T1 cancer cells; decreased the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and arginase activity of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice | Kaslowska et al. 2013 [17] |

| Lophocladia sp. | Lophocladines A and B are 2,7-naphthyridine alkaloids from Lophocladia sp. Lophocladine A has affinity for NMDA receptors and is a δ-opioid receptor antagonist; Lophocladine B was cytotoxic to NCI-H460 human lung tumor cells and MDAMB-435 breast cancer cells | Gross et al. 2006 [19] |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Ervik, M.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, IARC Cancer Base No. 11. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2013. Available online: http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Kim, E.J.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.H. Fucoidan present in brown algae induces apoptosis of human colon cancer cells. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.; Naishadham, D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacinti, L.; Claudio, P.P.; Lopez, M.; Giordano, A. Epigenetic information and estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. Oncologist. 2006, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Hua, H.; Jing, J.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Epigallocatechin gallate sensitizes breast cancer cells to paclitaxel in a murine model of breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, R8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulaski, B.A.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Mouse 4T1 breast tumor model. In Current Protocols in Immunology; Wiley Online Library: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001; Chapter 20, unit 20.22. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, D.M.; Cheel, J.; Arche, C.; San-Martin, A.; Rovirosa, J.; Silva, L.R.; Valentao, P.; Andrade, P.B. Anti-proliferative activity of meroditerpenoids isolated from the brown alga Stypopodium flabelliforme against several cancer cell lines. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.R.; Backlund, M.G.; DuBois, R.N. Mechanisms of disease: Inflammatory mediators and cancer prevention. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2005, 2, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namvar, F.; Mahamad, R.; Baharara, J.; Balnejah, S.Z.; Fargahi, F.; Rahman, H.S. Antioxidant, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenesis effects of polyphenol-rich seaweed (Sargassum muticum). Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 604787. [Google Scholar]

- Ramberg, J.E.; Nelson, E.D.; Sinnott, R.A. Immunomodulatory dietary polysaccharides: A systematic review of the literature. Nut. J. 2010, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.J.; Kim, A.D.; Kang, K.A.; Chung, H.S.; Kim, H.S.; Suh, I.S.; Chang, W.Y.; Hyun, J.W. The green algae Ulva fasciata Delile extract induces apoptotic cell death in human colon cancer cells. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2013, 49, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.K.; Kim, I.H.; Kim, J.; Nam, T.J. Induction of apoptosis by laminarin, regulating the insulin-like growth factor-IR signaling pathways in HT-29 human colon cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 734–738. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.K.; Kim, J.; Nam, T.J. Induction of apoptosis and regulation of ErbB signaling by laminarin in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, S.N.; Shubina, L.K.; Bode, A.M.; Stonik, V.A.; Dong, Z. Dactylone inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced transformation and phenotype expression of human cancer cells and induces G1-S arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 5914–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.M.; Rajapakse, N.; Kim, S.K. Anti-inflammatory effect of Ishighe okamurae ethanolic extract via inhibition of NF-kappaB transcription factor RAW264.7 cells. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.N.; Bhagavathula, N.; Paruchuri, T.; Hu, X.; Chakrabarty, S.; Varani, J. Growth-inhibitory of mineralized extract from red marine algae, Lithothamnion calcareum, on Ca²+-sensitive and Ca²+-resistant human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2009, 283, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- i>Kazlowska, K.; Victor Lin, H.T.; Chang, S.H.; Tsai, G.J. In vitro and in vivo anticancer effects of sterol fraction from red algae Porphyra dentata. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 2013, 493869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badal, S.; Gallimore, W.; Huang, G.; Tseng, T.R.J.; Delgoda, R. Cytotoxic and potent CYP1 inhibitors from the marine algae Cymopolia barbata. Org. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, H.; Goeger, D.E.; Hills, P.; Mooberry, S.L.; Bellatine, D.L.; Murray, T.F.; Valeriote, F.A.; Gerwick, W.H. Lopohocladines, bioactive alkaloids from the red alga Lophocladia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavia, H.; Aberg, P. Spatial variation in polyphenolic content of Ascophyllum nodosum (Fucales, Phaeophyta). Hydrobiologia 1996, 327, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yeh, C.C.; Lee, J.C.; Yi, S.C.; Huang, H.W.; Tseng, C.N.; Chang, H.W. Aqueous extracts of edible Gracilaria tenuistipitata are protective against HO induced DNA damage, growth inhibition, and cell cycle arrest. Molecules 2012, 17, 7241–7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Kundu, R. Antiproliferative activity of methanolic extracts from two green algae, Enteromorpha intestinalis and Rhizoclonium riparium, on HeLa cells. Daru 2013, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Lee, J.S.; Qian, Z.J.; Li, Y.X.; Kim, K.N.; Heo, S.J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Park, W.S.; Choi, I.W.; Je, J.Y.; et al. Gliotoxin isolated from marine fungus Aspergillus sp. induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer and chondrosarcoma cells. Mar. Drugs 2013, 12, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Teng, H.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Hou, L.; Zou, X. Fucoidan derived from Undaria pinnatifada induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC 7721 cells via the ROS mediated mitochondrial pathway. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1961–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WCRF/AICR: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Bedi, A.; Pasricha, P.J.; Akhtar, A.J.; Barber, J.P.; Bedi, G.C.; Giardiello, F.M.; Zehnbauer, B.A.; Hamilton, S.R.; Jones, J.R. Inhibition of apoptosis during development of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 1811–1816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, A.A.; Butt, G.; Razzaq, Z. Algae extracts and methyl jasmonate anti-cancer activities in prostate cancer: Choreographers of “the dance macabre”. Cancer Cell Int. 2012, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Mak, T.W. Mitochondrial cell death effectors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Seol, D.W. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep. 2008, 41, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellier, G.; Huang, G.; Shenoy, K.; Pervaiz, S. TRAILing death in cancer. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010, 31, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; GE, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wanq, Q.; Hou, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, Q. Anticancer properties and mechanisms of fucoidan on mouse breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enari, M.; Talanian, R.V.; Wong, W.W.; Nagata, S. Sequential activation of ICE-like and CPP32-like proteases during Fas-mediated apoptosis. Nature 1996, 380, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kischkel, F.C.; Hellbardt, S.; Behrmann, I.; Germer, M.; Pawlita, M.; Krammer, P.H.; Peter, M.E. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 5579–5588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salvesen, G.S.; Dixit, V.M. Caspases: Intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell 1997, 91, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynes, N.E.; Lane, H.A. ERBB receptors and cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citri, A.; Yarden, Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: Towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, D.S.; Brandt, R.; Ciardiello, F.; Normanno, N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 1995, 19, 183–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lu, F.; Wein, X.; Zhao, R. Fucoidan: Structure and bioactivity. Molecules 2008, 13, 1671–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilan, M.I.; Grachev, A.A.; Ustuzhanina, N.E.; Shashkov, A.S.; Nifantiev, N.E.; Usov, A.I. Structure of fucoidan from the brown seaweed Fucus evanescences C.Ag. Carbohydr. Res. 2002, 337, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, M.I.; Grachev, A.A.; Shashkov, A.S.; Nifantiev, N.E.; Usov, A.I. Structure of a fucoidan from the brown seaweed Fucus serratus L. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Itoh, H.; Noda, H.; Amano, H.; Zhuaug, C.; Mizuno, T.; Ito, H. Antitumor activity and immunological properties of marine algal polysaccharides, especially fucoidan, prepared from Sargassum thunbergii of Phaeophyceae. Anticancer Res. 1993, 13, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, C.; Itoh, H.; Mizuno, T.; Ito, H. Antitumor active fucoidan from the brown seaweed umitoranoo (Sargassum thubergii). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseyenko, T.V.; Zhanayeva, S.Y.; Venediktova, A.A.; Zvyagintseva, T.N.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Besednova, N.N.; Korolenko, T.A. Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide isolate from the Okhotsk Sea Fucus evanescens brown alga. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2007, 143, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, D.; Colliec-Jouault, S.; Pinczon du Sel, D.; Bosch, S.; Siavoshian, S.; le Bert, V.; Tomasoni, C.; Sinquin, C.; Durand, P.; Roussakis, C. Antitumor and antiproliferative effects of a fucan extracted from ascophyllum nodosum against a non-small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma line. Anticancer Res. 1996, 16, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Aisa, Y.; Miyakawa, Y.; Nakazato, T.; Shibata, H.; Saito, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Kizaki, M. Fucoidan induces apoptosis of human HS-sultan cells accompanied by activation of caspase-3 and down-regulation of ERK pathways. Am. J. Hematol. 2005, 78, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruya, T.; Konishi, T.; Uechi, S.; Tamaki, H.; Tako, M. Anti-proliferative activity of oversulfated fucoidan from commercially cultured Cladosiphon okamuranus TOKIDA in U937 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 41, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombe, D.R.; Parish, C.R.; Ramshaw, I.A.; Snowden, J.M. Analysis of the inhibition of tumor metastasis by sulphated polysaccharides. Int. J. Cancer 1987, 39, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Li, Y.; Teruya, K.; Katakura, Y.; Ichikawa, A.; Eto, H.; Hosoi, M.; Nishimoto, S.; Shirahata, S. Enzyme-digested fucoidan extracts derived from seaweed mozuku of Cladosiphon novae-caledoniae kylin inhibit invasion and angiogenesis of tumor cells. Cytotechnology 2005, 47, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, H.J.; Hyun, J.H.; Kim, S.C.; Kang, J.I.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, H.; Yoo, E.S.; Kang, H.K. Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida induces apoptosis in A549 human lung carcinoma cells. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 1082–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, J.H.; Kim, S.C.; Kang, J.I.; Kim, M.K.; Boo, H.J.; Kwon, J.M.; Koh, Y.S.; Hyun, J.W.; Park, D.B.; Yoo, E.S.; et al. Apoptosis inducing activity of fucoidan in HCT 15 colon carcinoma cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 1760–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, M.L.; Robertson, A.S.; Rodriguez, C.; Jacobs, E.J.; Chao, A.; Carolyn, J.; Calle, E.E.; Willett, W.C.; Thun, M.J. Calcium, vitamin D, dairy products, and risk of colorectal cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2003, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood, A.; Peters, U.; Chatterjee, N.; Lacey, J.V., Jr.; Schairer, C.; Schatzkin, A. Calcium from diet and supplements is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective cohort of women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bostick, R.M.; Potter, J.D.; Sellers, T.A.; McKenzie, D.R.; Kushi, L.H.; Folsom, A.R. Relation of calcium, vitamin D and dairy food intake to incidence of colon cancer among older women. The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1993, 137, 1302–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Kampman, E.; Giovannucci, E.; Veer, P.V.; Rimm, E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Kok, F.J.; Willett, W.C. Calcium, vitamin D, dairy foods, and the occurrence of colorectal adenomas among men and women in two prospective studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 139, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kampman, E.; Slattery, M.L.; Caan, B.; Potter, J.D. Calcium, vitamin D, sunshine exposure, dairy products and colon cancer risk (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, J.A.; Beach, M.; Mandel, J.S.; van Stolk, R.U.; Haile, R.W.; Sandler, R.S.; Rothstein, R.; Summers, R.W.; Snover, D.C.; Beck, G.J.; et al. Calcium supplements for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Calcium Polyp Prevention Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, M.V.; Baron, J.A.; Sandler, R.S.; Haile, R.W.; Beach, M.L.; Church, T.R.; Heber, D. Vitamin D, calcium supplementation, and colorectal adenomas: Results of a randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.R.; Reed, J.C. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 1998, 281, 1309–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Huang, C.Y.; Zheng, R.L.; Cui, K.R.; Li, J.F. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptosis in human hepatoma cells and alters cell redox status. Cell Biol. Int. 2000, 24, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanguinetti, A.; Polisterna, A.; D’Ermo, G.; Lucchini, R.; Triola, R.; Conti, C.; Avenia, S.; Cavallaro, G.; de Toma, G.; Avenia, N. Male breast cancer in the twenty-first century: What’s new? Ann. Ital. Chir. 2014, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Heinrich, M.; Myers, S.; Dworjanyn, S.A. Towards a better understanding of medicinal uses of the brown seaweed Sargassum in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A phytochemical and pharmacological review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 142, 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, M.C.; Kim, E.; Nam, T.J.; Fujii, H.; Hong, Y.K. Anti-inflammatory activities of methanol extracts from various seaweed species. J. Environ. Biol. 2008, 29, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Funahashi, H.; Imai, T.; Mase, T.; Sekiya, M.; Yokoi, K.; Hayashi, H.; Shibata, A.; Hayashi, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Suda, M.; et al. Seaweed prevents breast cancer? Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2001, 92, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, H.; Taumachi, H.; Lizuka, M.; Nakano, T. The role of NK cells in antitumor activity of dietary fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida sporophylls (Mekabu). Planta Medica 2006, 72, 1415–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.B.; Fink, C.S. Phytosterols as anticancer dietary components: Evidence and mechanism of action. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2127–2130. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, A.B.; Fink, C.S.; Williams, H.; Kim, U. In vitro and in vivo (SCID mice) effects of phytosterols on the growth and dissemination of human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2001, 10, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Holtz, R.L.; Fink, C.S.; Awad, A.B. beta-Sitosterol activates the sphingomyelin cycle and induces apoptosis in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Nutr. Cancer 1998, 32, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.C.; Zea, A.H.; Hernandez, C.; Rodrigue, P.C. Arginase, prostaglandins, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 721s–726s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zea, A.H.; Rodriguez, P.C.; Atkins, M.B.; Hernandez, C.; Signoretti, S.; Zabaleta, J.; McDermott, D.; Quiceno, D.; Youmans, A.; O’Neill, A.; et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: A mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 3044–3048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Karimian, H.; Khanabdali, R.; Razavi, M.; Firoozinia, M.; Zandi, K.; Abdul Kadir, H. Anticancer and Antitumor Potential of Fucoidan and Fucoxanthin, Two Main Metabolites Isolated from Brown Algae. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 768323:1–768323:10. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Moussavou, G.; Kwak, D.H.; Obiang-Obonou, B.W.; Maranguy, C.A.O.; Dinzouna-Boutamba, S.-D.; Lee, D.H.; Pissibanganga, O.G.M.; Ko, K.; Seo, J.I.; Choo, Y.K. Anticancer Effects of Different Seaweeds on Human Colon and Breast Cancers. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 4898-4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12094898

Moussavou G, Kwak DH, Obiang-Obonou BW, Maranguy CAO, Dinzouna-Boutamba S-D, Lee DH, Pissibanganga OGM, Ko K, Seo JI, Choo YK. Anticancer Effects of Different Seaweeds on Human Colon and Breast Cancers. Marine Drugs. 2014; 12(9):4898-4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12094898

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoussavou, Ghislain, Dong Hoon Kwak, Brice Wilfried Obiang-Obonou, Cyr Abel Ogandaga Maranguy, Sylvatrie-Danne Dinzouna-Boutamba, Dae Hoon Lee, Ordelia Gwenaelle Manvoudou Pissibanganga, Kisung Ko, Jae In Seo, and Young Kug Choo. 2014. "Anticancer Effects of Different Seaweeds on Human Colon and Breast Cancers" Marine Drugs 12, no. 9: 4898-4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12094898

APA StyleMoussavou, G., Kwak, D. H., Obiang-Obonou, B. W., Maranguy, C. A. O., Dinzouna-Boutamba, S.-D., Lee, D. H., Pissibanganga, O. G. M., Ko, K., Seo, J. I., & Choo, Y. K. (2014). Anticancer Effects of Different Seaweeds on Human Colon and Breast Cancers. Marine Drugs, 12(9), 4898-4911. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12094898