Expression of the Grape VaSTS19 Gene in Arabidopsis Improves Resistance to Powdery Mildew and Botrytis cinerea but Increases Susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringe pv Tomato DC3000

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. VaSTS19 Expression is Induced in Grape Following Powdery Mildew Infection

2.2. Analysis of VaSTS19-Expressing Transgenic Arabidopsis Lines

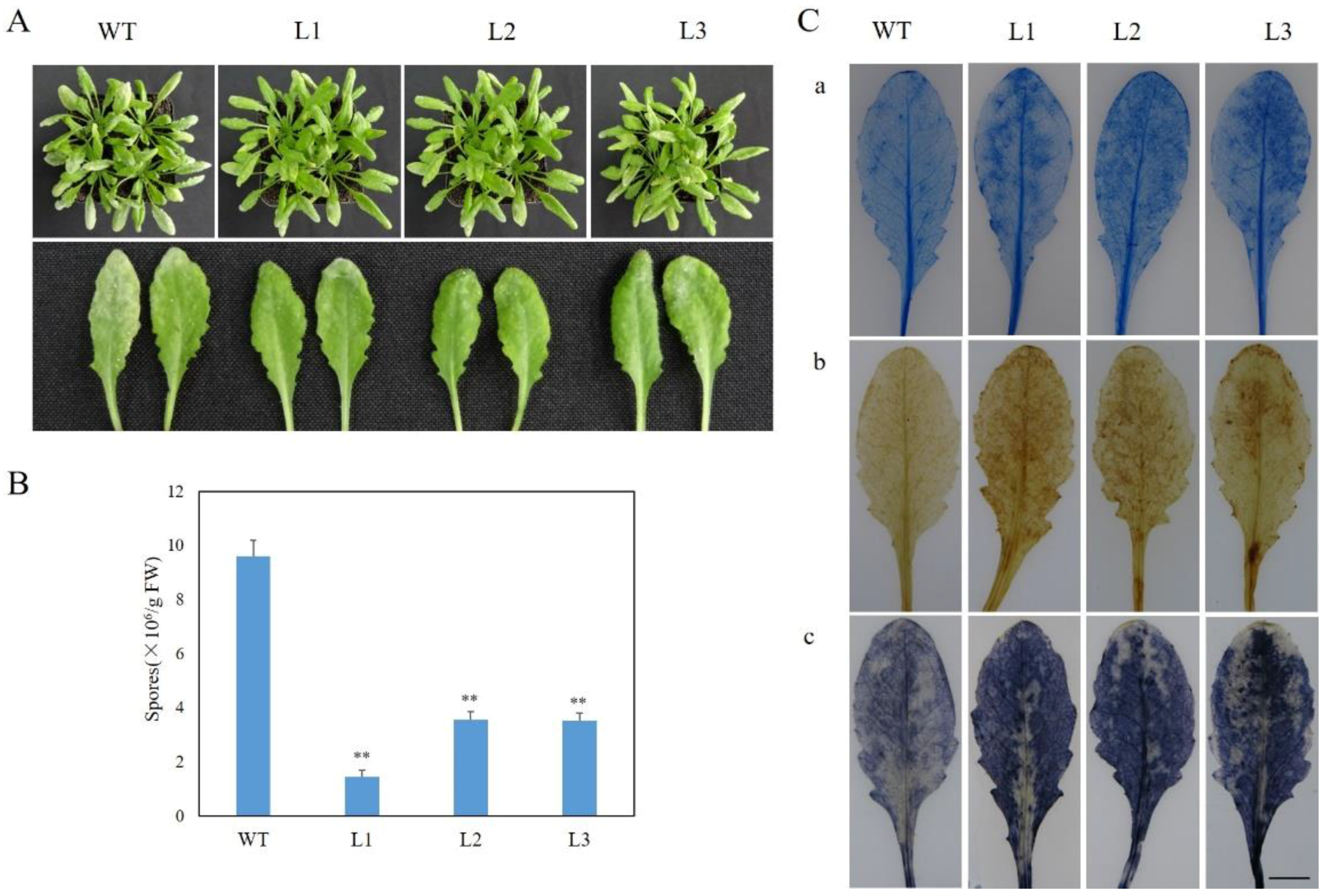

2.3. Expression of VaSTS19 in Arabidopsis Increases Resistance to Powdery Mildew

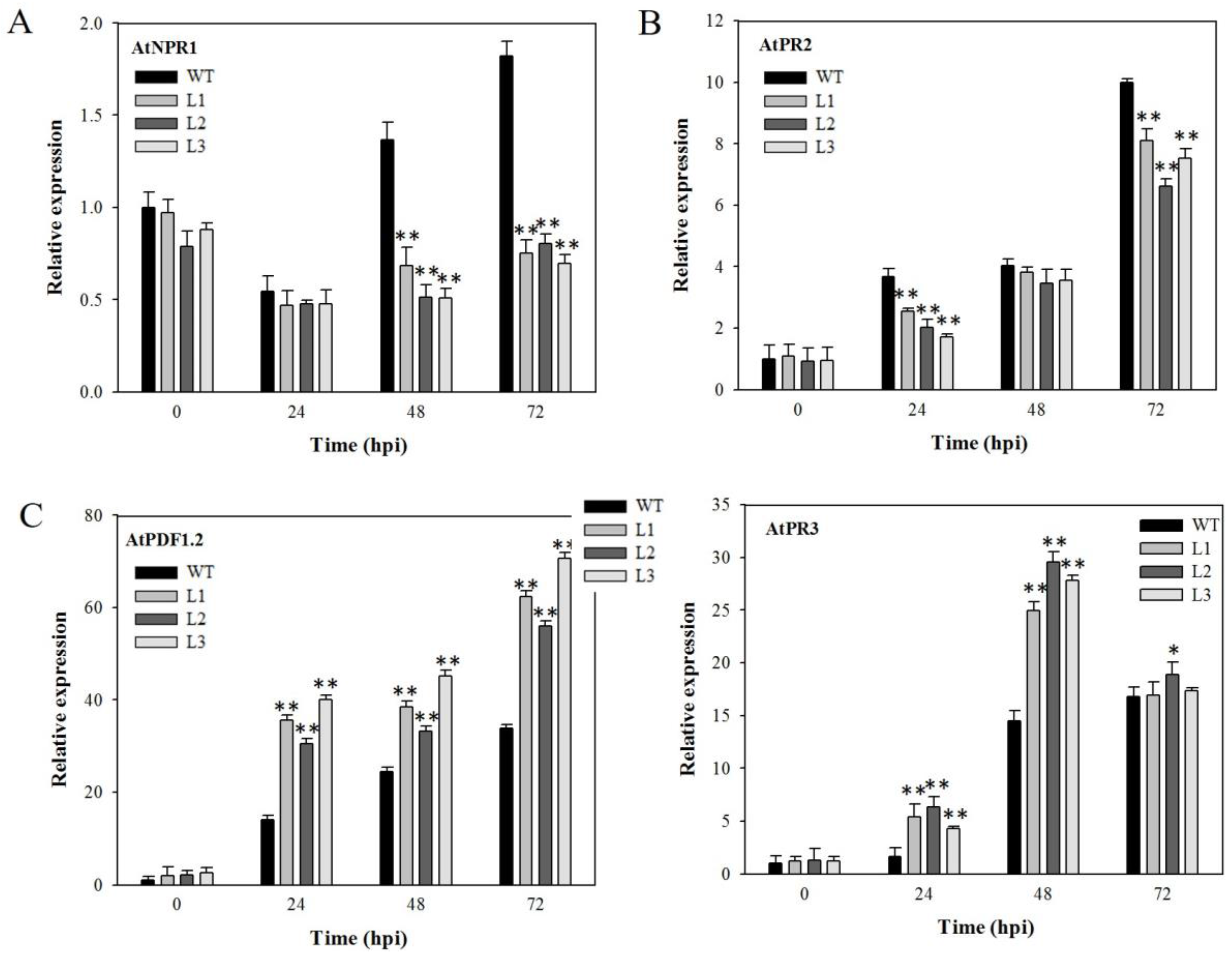

2.4. Expression Analysis of Disease-Resistance-Related Genes in VaSTS19-Expressing Arabidopsis Lines Following Powdery Mildew Infection

2.5. Expression of VaSTS19 in Arabidopsis Enhances Resistance to B. cinerea

2.6. Expression Analysis of Disease-Resistance-Related Genes in VaSTS19-Expressing Plants Following B. cinerea Infection

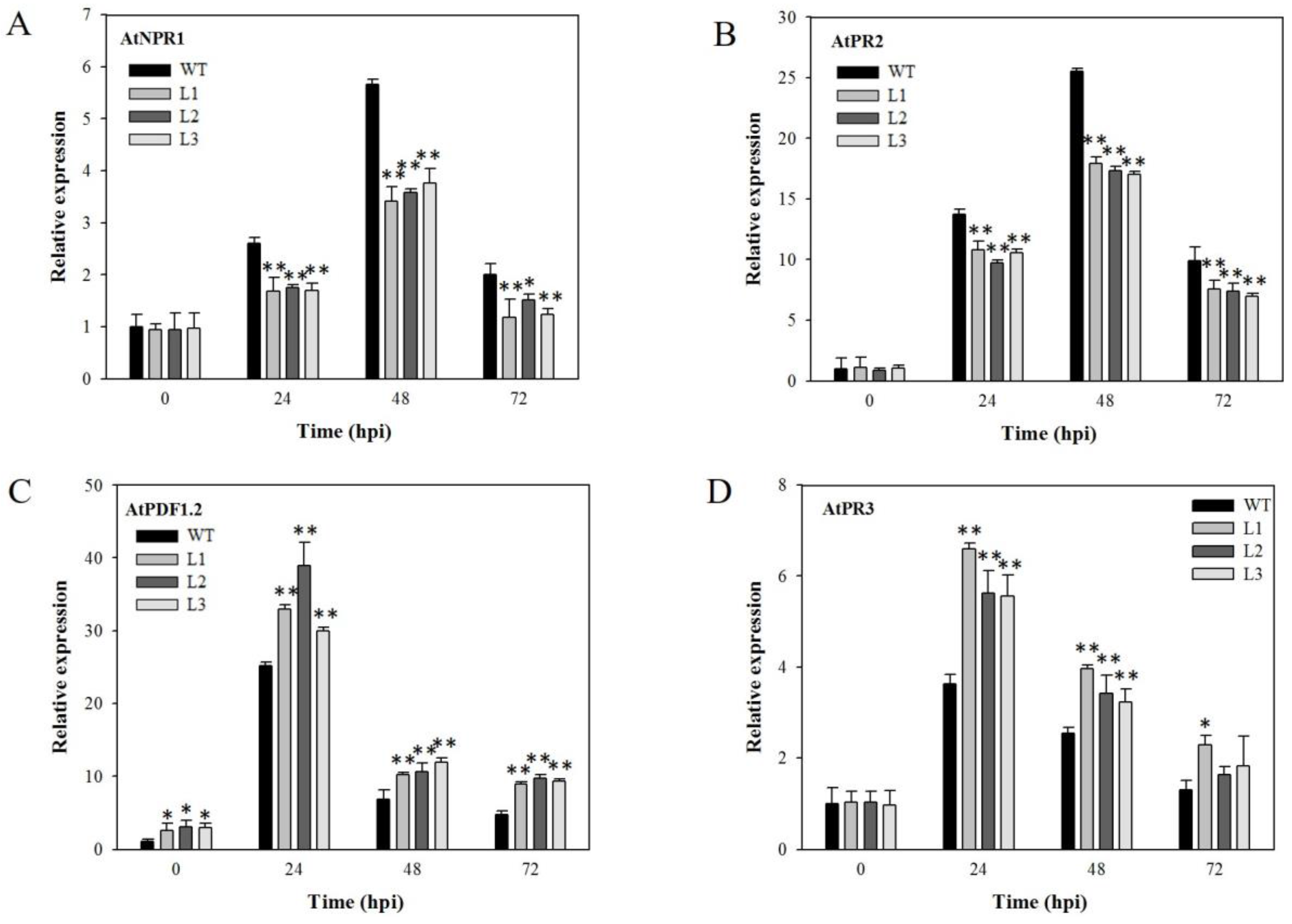

2.7. VaSTS19-Expressing Arabidopsis Lines Show Decreased Resistance to PstDC3000

2.8. Analysis of Disease-Resistance-Related Genes in VaSTS19-Expressing Plants Following PstDC3000 Infection

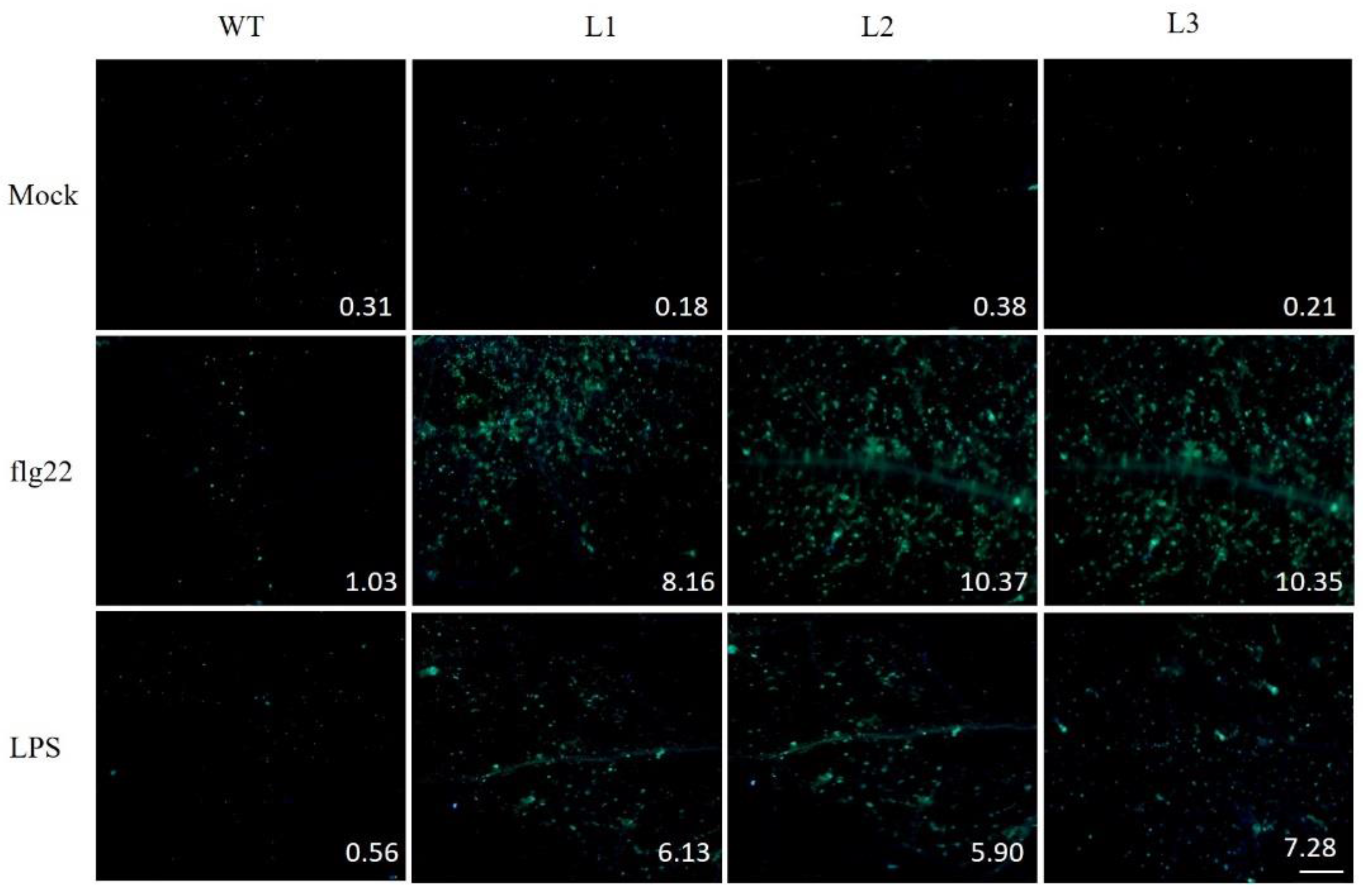

2.9. PAMP-Triggered Callose Deposition in VaSTS19-Expressing Lines and Nontransgenic Control Plants

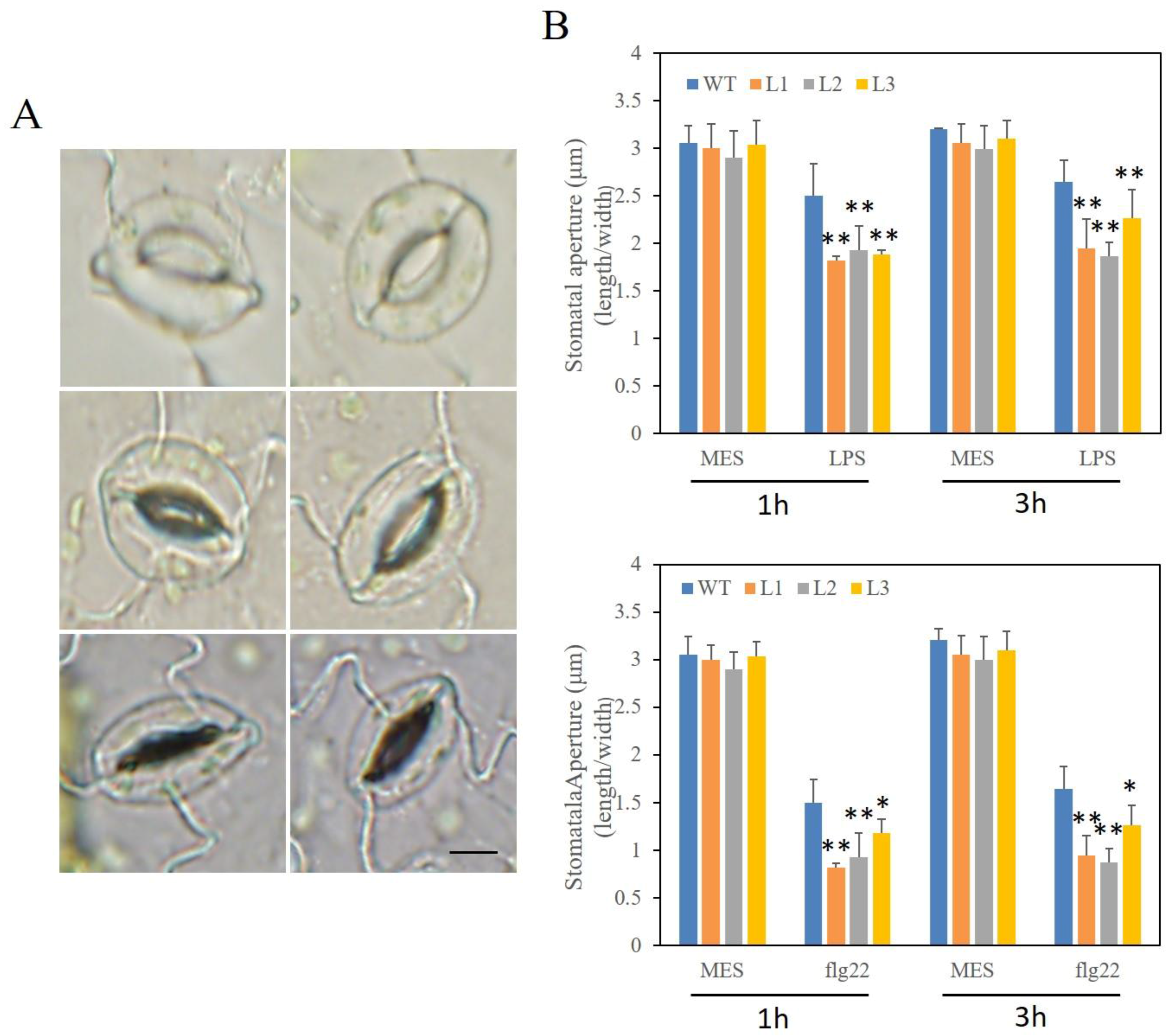

2.10. Altered Stomatal Immunity Responses in VaSTS19-Expressing Arabidopsis Lines and Nontransgenic Control Plants

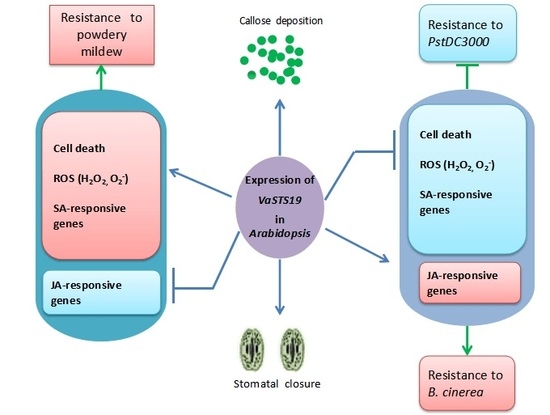

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Pathogenic Bacteria

4.2. Inoculation with Powdery Mildew in Grape

4.3. RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.4. Generation of Transgenic Plants Expressing the VaSTS19 Gene

4.5. Inoculation of Arabidopsis Pathogen

4.6. Histochemical Detection of Cell Death and Superoxide Accumulation

4.7. Observation of Qualitative Stoma and Callose under Biotic Stresses

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STS | stilbene synthase |

| CaMV | cauliflower mosaic virus |

| pad4 | phytoalexin deficient 4 |

| MS | murashige and skoog |

| CoA | coenzyme A |

| HEPES | 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| MES | 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid |

| PstDC3000 | Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomatoDC3000 |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| hpi | hours post inoculation |

| dpi | days post inoculation |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| NPR1 | nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related gene |

| PR2 | pathogenesis-related gene 2 |

| PDF1.2 | plant defensing 1.2 |

| PR3 | pathogenesis-related gene 3 |

| NBT | nitro blue tetrazolium |

| DAB | diaminobenzidine |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharides |

| Flg22 | flagellin fragment |

| PAMP | pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| UCSC1 | Erysiphe cichoracearum |

| PCD | programmed cell death |

| PTI | PAMP-triggered immunity |

References

- Zhu, Z.; Shi, J.; Cao, J.; He, M.; Wang, Y. VpWRKY3, a biotic and abiotic stress-related transcription factor from the Chinese wild Vitis pseudoreticulata. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar]

- Mzid, R.; Marchive, C.; Blancard, D.; Deluc, L.; Barrieu, F.; Corio-Costet, M.-F.; Drira, N.; Hamdi, S.; Lauvergeat, V. Overexpression of VvWRKY2 in tobacco enhances broad resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. Physiol. Plant 2007, 131, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Wan, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Ectopic expression of a grape aspartic protease gene, AP13, in Arabidopsis thaliana improves resistance to powdery mildew but increases susceptibility to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Sci. 2016, 248, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Harrison, M.J. Activation, structure, and organization of genes involved in microbial defense in plants. Adv. Genet. 1990, 28, 165–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Derckel, J.P.; Baillieul, F.; Manteau, S.; Audran, J.C.; Haye, B.; Lambert, B.; Legendre, L. Differential induction of grapevine defenses by two strains of Botrytis cinerea. Phytopathology 1999, 89, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeandet, P.; Douillet-Breuil, A.C.; Bessis, R.; Debord, S.; Sbaghi, M.; Adrian, M. Phytoalexins from the Vitaceae: Biosynthesis, phytoalexin gene expression in transgenic plants, antifungal activity and melabolism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuc, J. Phytoalexins, stress metabolism, and disease resistance in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1995, 33, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkayashta, R.P. Progress in phytoalexin research during the past 50 years. In Handbook of Phytoalexin Metabolism and Action; Daniel, M., Purkayashta, R.P., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J.B. The comparative biochemistry of phytoalexin induction in plants. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1999, 27, 335–367. [Google Scholar]

- Serazetdinova, L.; Oldach, K.H.; Lörz, H. Expression of transgenic stilbene synthases in wheat causes the accumulation of unknown stilbene derivatives with antifungal activity. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 162, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treutter, D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2006, 4, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Q.-H.; Wang, L.; Li, J.-M. Amounts and subcellular localization of stilbene synthase in response of grape berries to UV irradiation. Plant Sci. 2009, 176, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.K.; Springob, K.; Schmidt, J.; Nicholson, R.L.; Chu, I.K.; Yip, W.K.; Lo, C. A stilbene synthase gene (SbSTS1) is involved in host and nonhost defense responses in sorghum. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Counet, C.; Callemien, D.; Collin, S. Chocolate and cocoa: New sources of trans-resveratrol and trans-piceid. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, A.J.; Murphy, P.J.; Dry, I.B. The molecular regulation of stilbene phytoalexin biosynthesis in Vitis. vinifera during grape berry development. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 27, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versari, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Tornielli, G.B.; Ferrarini, R.; Giulivo, C. Stilbene compounds and stilbene synthase expression during ripening, wilting, and UV treatment in grape cv. Corvina. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5531–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borra, M.T.; Smith, B.C.; Denu, J.M. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17187–17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannozzi, A.; Dry, I.B.; Fasoli, M.; Zenoni, S.; Lucchin, M. Genome-wide analysis of the grapevine stilbene synthase multigenic family: Genomic organization and expression profiles upon biotic and abiotic stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, W.; Yu, Y.; Ding, J.; Hua, Z.; Wang, Y. Characterization of a novel stilbene synthase promoter involved in pathogen- and stress-inducible expression from Chinese wild Vitis pseudoreticulata. Planta 2009, 231, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.K.Y.; Lam, C.N.W.; Springob, K.; Schmidt, J.; Chu, I.K.; Lo, C. Constitutive accumulation of cis-piceid in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing a sorghum stilbene synthase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Xie, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Genetic transformation of a fruit-specific, highly expressed stilbene synthase gene from Chinese wild Vitis quinquangularis. Planta 2016, 243, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hain, R.; Reif, H.J.; Krause, E.; Langebartels, R.; Kindl, H.; Vornam, B.; Wiese, W.; Schmelzer, E.; Schreier, P.H.; Stöcker, R.H. Disease resistance results from foreign phytoalexin expression in a novel plant. Nature 1993, 361, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark-Lorenzen, P.; Nelke, B.; Hänßler, G.; Mühlbach, H.P.; Thomzik, J.E. Transfer of a grapevine stilbene synthase gene to rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Rep. 1997, 16, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Ge, H.; Howard, S.; Qiu, W. Transcriptional expression of stilbene synthase genes are regulated developmentally and differentially in response to powdery mildew in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon grapevine. Plant Sci. 2012, 197, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Singer, S.D.; Qiao, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Fei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Wang, X. Insights into the mechanisms underlying ultraviolet-C induced resveratrol metabolism in Grapevine (V. amurensis Rupr.) cv. “Tonghua-3”. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Expression patterns and promoter characteristics of the Vitis quinquangularis VqSTS36 gene involved in abiotic and biotic stress response. Protoplasma 2017, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiselev, K.; Tyunin, A.; Karetin, Y. Salicylic acid induces alterations in the methylation pattern of the VaSTS1, VaSTS2, and VaSTS10 genes in Vitis amurensis Rupr. cell cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellinger, D.; Naumann, M.; Falter, C.; Zwikowics, C.; Jamrow, T.; Manisseri, C.; Somerville, S.C.; Voigt, C.A. Elevated early callose deposition results in complete penetration resistance to powdery mildew in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleynova-Shumakova, O.A.; Dubrovina, A.S.; Manyakhin, A.Y.; Karetin, Y.A.; Kiselev, K.V. VaCPK20 gene overexpression significantly increased resveratrol content and expression of stilbene synthase genes in cell cultures of Vitis amurensis Rupr. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 5541–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingham, J.L. 3, 5, 4′-Trihydroxystilbene as a phytoalexin from groundnuts (Arachis hypogaea). Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 1791–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, F.; Hohmann, F.; Schwer, B.; Kindl, H. Induction of stilbene synthase by Botrytis cinerea in cultured grapevine cells. Planta 1991, 183, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A.; Jacobsen, H.J.; de Kathen, A.; de Lorenzo, G.; Briviba, K.; Hain, R.; Ramsay, G.; Kiesecker, H. Transgenic peas (Pisum sativum) expressing polygalacturonase inhibiting protein from raspberry (Rubus idaeus) and stilbene synthase from grape (Vitis vinifera). Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leckband, G.; Lorz, H. Transformation and expression of a stilbene synthase gene of Vitis vinifera L. in barley and wheat for increased fungal resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1998, 96, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; Agbayani, R.; Jackson, M.C.; Tang, C.; Moore, P.H. Expression of the grapevine stilbene synthase gene VST1 in papaya provides increased resistance against diseases caused by Phytophthora palmivora. Planta 2004, 220, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorcelli, A.; Sparvoli, F.; Mattivi, F.; Tava, A.; Balestrazzi, A.; Vrhovsek, U.; Calligari, P.; Bollini, R.; Confalonieri, M. Expression of the stilbene synthase (STSy) gene from grapevine in transgenic white poplar results in high accumulation of the antioxidant resveratrol glucosides. Transgenic Res. 2004, 13, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J.; Lin, Z. High content of resveratrol in lettuce transformed with a stilbene synthase gene of Parthenocissus henryana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8082–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnee, S.; Viret, O.; Gindro, K. Role of stilbenes in the resistance of grapevine to powdery mildew. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 72, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szankowski, I.; Briviba, K.; Fleschhut, J.; Schönherr, J.; Jacobsen, H.; Kiesecker, H. Transformation of apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) with the stilbene synthase gene from grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) and a PGIP gene from kiwi (Actinidia deliciosa). Plant Cell Rep. 2003, 22, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Xu, W.; Duan, D.; Wang, Y.; Nick, P. A stilbene synthase allele from a Chinese wild grapevine confers resistance to powdery mildew by recruiting salicylic acid signalling for efficient defence. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 5841–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J.T.; Yao, N. The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant–pathogen interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 2004, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, S.; Singer, S.D.; Yin, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Expression of the Grape VqSTS21 gene in Arabidopsis confers resistance to osmotic stress and biotrophic pathogens but not Botrytis cinerea. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakannan, M.; Bose, J.; Babourina, O.; Rengel, Z.; Shabala, S. Salicylic acid in plant salinity stress signalling and tolerance. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 76, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J. The salicylic acid loop in plant defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Y.; Fan, J.Y.; Hua, C.P.; Yan, W.; Chen, C.J.; Lu, Y.H.; Jiao, R.H.; Tan, R.X. Resveratrol improves fungal ribosylation capacity through a unique mechanism. Rsc. Adv. 2014, 5, 5657–5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, H.M.; Selvendran, R.R.; Bowles, D.J. The wound response of tomato plants can be inhibited by aspirin and related hydroxy-benzoic acids. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1988, 33, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, P.M.; Kazan, K.; Wilson, I.; Anderson, J.P.; Richmond, T.; Somerville, S.C.; Manners, J.M. Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11655–11660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mur, L.A.; Kenton, P.; Atzorn, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C. The outcomes of concentration-specific interactions between salicylate and jasmonate signaling include synergy, antagonism, and oxidative stress leading to cell death. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Chang, P.-F.L.; Liu, D.; Narasimhan, M.L.; Raghothama, K.G.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bressan, R.A. Plant defense genes are synergistically induced by ethylene and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomma, B.P.; Eggermont, K.; Broekaert, W.F.; Cammue, B.P. Disease development of several fungi on Arabidopsis can be reduced by treatment with methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2000, 38, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, N.; Metz, M.; Holub, E.; Staskawicz, B.J.; Daniels, M.J.; Parker, J.E. Different requirements for EDS1 and NDR1 by disease resistance genes define at least two R gene-mediated signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10306–10311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Molina, A.; Solano, R. Constitutive expression of ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1 in Arabidopsis confers resistance to several necrotrophic fungi. Plant J. 2002, 29, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.M.; Bender, C.L.; Kunkel, B.N. The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 6, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurie-Berry, N.; Joardar, V.; Street, I.H.; Kunkel, B.N. The Arabidopsis thaliana JASMONATE INSENSITIVE 1 gene is required for suppression of salicylic acid-dependent defenses during infection by Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.W.; Morris, V.L.; Cuppels, D.A. Characterization of a DNA region required for production of the phytotoxin coronatine by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991, 4, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Bahrami, A.K.; Pringle, E.G.; Hernandez-Guzman, G.; Bender, C.L.; Pierce, N.E.; Ausubel, F.M. Pseudomonas syringae manipulates systemic plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gómez, L.; Felix, G.; Boller, T. A single locus determines sensitivity to bacterial flagellin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1999, 18, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuber, T.L.; Plotnikova, J.M.; Dewdney, J.; Rogers, E.E.; Wood, W.; Ausubel, F.M. Correlation of defense gene induction defects with powdery mildew susceptibility in Arabidopsis enhanced disease susceptibility mutants. Plant J. 1998, 16, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornero, P.; Dangl, J.L. A high-throughput method for quantifying growth of phytopathogenic bacteria in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2001, 28, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, J.R.; Kikkert, J.R.; Malnoy, M.A.; Wallace, P.G.; Barnard, J.; Reisch, B.I. Evaluation of transgenic “Chardonnay” (Vitis vinifera) containing magainin genes for resistance to crown gall and powdery mildew. Transgenic Res. 2006, 15, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Ellwood, S.; Findlay, K.; Oliver, R.P.; Turner, J.G. Characterization of three loci controlling resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana accession Ms-0 to two powdery mildew diseases. Plant J. 1997, 12, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y. Expression and functional analysis of two genes encoding transcription factors, VpWRKY1 and VpWRKY2, isolated from Chinese wild Vitis pseudoreticulata. Planta 2010, 232, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Hénanff, G.; Profizi, C.; Courteaux, B.; Rabenoelina, F.; Gérard, C.; Clément, C.; Baillieul, F.; Cordelier, S.; Dhondt-Cordelier, S. Grapevine NAC1 transcription factor as a convergent node in developmental processes, abiotic stresses, and necrotrophic/biotrophic pathogen tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4877–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thordal-Christensen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Collinge, D.B. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the Barley—Powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 1997, 11, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.; Slusarenko, A. Arabidopsis is susceptible to infection by a downy mildew fungus. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Guo, R.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J.; Wang, X. Expression of a grape bZIP transcription factor, VqbZIP39, in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers tolerance of multiple abiotic stresses. PCTOC 2016, 125, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melotto, M.; Underwood, W.; Koczan, J.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y. Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell 2006, 126, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidler, D.; Zähringer, U.; Gerber, I.; Dubery, I.; Hartung, T.; Bors, W.; Hutzler, P.; Durner, J. Innate immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana: Lipopolysaccharides activate nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and induce defense genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15811–15816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, C.; Robatzek, S.; Navarro, L.; Oakeley, E.J.; Jones, J.D.; Felix, G.; Boller, T. Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature 2004, 428, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Forward and Reverse Primers(5′–3′) | Restriction Enzyme Cutting Site |

|---|---|---|

| VaSTS19-F1 | F:CGGGCTAATTTGAATATGTAA | - |

| VaSTS19-R1 | R:CGGTAAGGGTCATAGTGCAGCT | - |

| VaSTS19-F2 | F:CGCGGATCCGCGATGGCGTCTGTGGAGGAAA | BamHI site underlined |

| VaSTS19-R2 | R:TCCCCCGGGGGATTAGTTGGAATCTGTACCA | XmaI site underlined |

| AtNPR1-F | F:GCTCTGCTCGTCAATGGTTATC | - |

| AtNPR1-R | R:GAGGAGTCGGTGTTATCGGTA | - |

| AtPR2-F | F:CGGTACATCAACGTTGGAA | - |

| AtPR2-R | R:GCGTAGTCTAGATGGATGTT | - |

| AtPR3-F | F:CGCTTGTCCTGCTAGAGGTT | - |

| AtPR3-R | R:GCTCGGTTCACAGTAGTCTGA | - |

| AtPDF1.2-F | F:TCATGGCTAAGTTTGCTTCC | - |

| AtPDF1.2-R | R:AATACACACGATTTAGCACC | - |

| AtActin1-F | F:TCAATCCAGGAGATGTTTAGG | - |

| AtActin1-R | R:ACTGCTGGTACTCTGCGACA | - |

| VaActin-F | F:GATTCTGGTGATGGTGTGAGT | - |

| VaActin-R | R:GACAATTTCCCGTTCAGCAGT | - |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, F.; Huang, L.; Tian, X.; Van Nocker, S.; Gao, H.; Wang, X. Expression of the Grape VaSTS19 Gene in Arabidopsis Improves Resistance to Powdery Mildew and Botrytis cinerea but Increases Susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringe pv Tomato DC3000. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18092000

Wang Y, Wang D, Wang F, Huang L, Tian X, Van Nocker S, Gao H, Wang X. Expression of the Grape VaSTS19 Gene in Arabidopsis Improves Resistance to Powdery Mildew and Botrytis cinerea but Increases Susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringe pv Tomato DC3000. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(9):2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18092000

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yaqiong, Dejun Wang, Fan Wang, Li Huang, Xiaomin Tian, Steve Van Nocker, Hua Gao, and Xiping Wang. 2017. "Expression of the Grape VaSTS19 Gene in Arabidopsis Improves Resistance to Powdery Mildew and Botrytis cinerea but Increases Susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringe pv Tomato DC3000" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 9: 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18092000