Isolation and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria from the Gut of Holotrichia parallela Larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

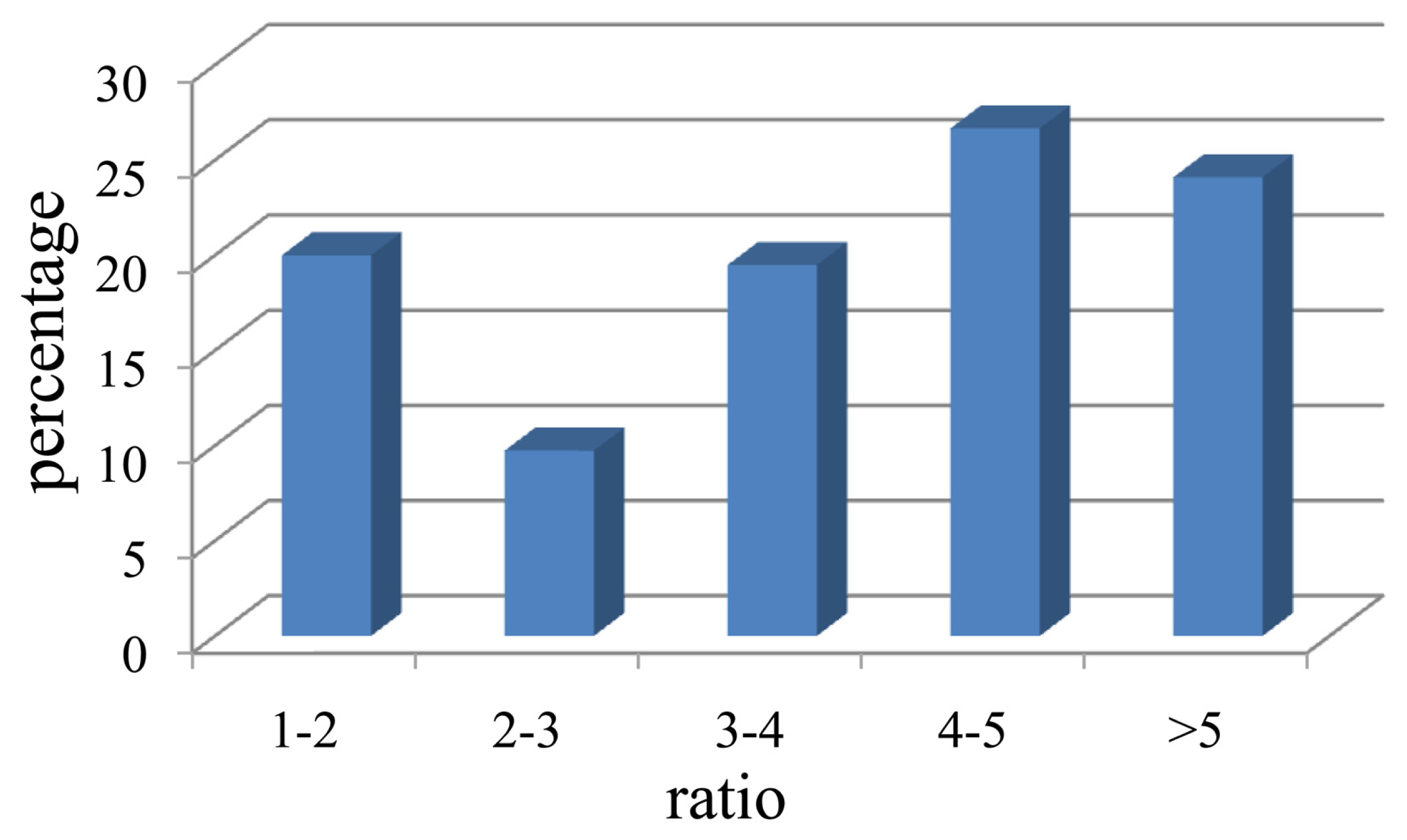

2.1. Isolation of Cellulolytic Bacteria

2.2. Assignment and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Insect and Dissection

3.2. Media

3.3. Counting and Isolation of Cellulolytic Bacteria

3.4. CMCase Activity Assay

3.5. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification of 16S rDNA

3.6. Genotyping of Bacterial Isolates by ARDRA

3.7. 16S rDNA Sequencing Analysis

3.8. Identification of Cellulolytic Isolates

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Sun, J.Z.; Scharf, M.E. Exploring and integrating cellulolytic systems of insects to advance biofuel technology. Insect Sci 2010, 17, 163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lynd, L.R.; Cushman, J.H.; Nichols, R.J.; Wyman, C.E. Fuel ethanol from cellulosic biomass. Science 1991, 251, 1318–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Lynd, L.R.; Laser, M.S.; Bransby, D.; Dale, B.E.; Davison, B.; Hamilton, R.; Himmel, M.; Keller, M.; McMillan, J.D.; Sheehan, J.; et al. How biotech can transform biofuels. Nat. Biotechnol 2008, 26, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Choo, Y.M.; Lee, K.S.; Hong, S.J.; Seol, K.Y.; Je, Y.H.; Sohn, H.D.; Jin, B.R. Molecular cloning and characterization of a glycosyl hydrolase family 9 cellulase distributed throughout the digestive tract of the cricket Teleogryllus emma. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol 2008, 150, 368–376. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Ó.J.; Cardona, C.A. Trends in biotechnological production of fuel ethanol from different feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 5270–5295. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, K. Us biofuels: A field in ferment. Nature 2006, 444, 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Badger, P.C. Ethanol from Cellulose: A General Review. In Trends in New Crops and New Uses; Janick, J., Whipkey, A., Eds.; American Society for Horticultural Science (ASHS) Press: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2002; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hamelinck, C.N.; van Hooijdonk, G.; Faaij, A.P.C. Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: Techno-economic performance in short-, middle- and long-term. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 28, 384–410. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Ahmetovic, E.; Grossmann, I.E. Optimization of water consumption in second generation bioethanol plants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2010, 50, 3705–3721. [Google Scholar]

- Mabee, W.E.; Saddler, J.N. Bioethanol from lignocellulosics: Status and perspectives in Canada. Bioresour. Technol 2010, 101, 4806–4813. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas, A. Options and trends of thorium fuel utilization in turkey. Energy Sources 2005, 27, 597–603. [Google Scholar]

- Balat, M.; Balat, H.; Öz, C. Progress in bioethanol processing. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci 2008, 34, 551–573. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, T.; Börjesson, J.; Tjerneld, F. Mechanism of surfactant effect in enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2002, 31, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, S.; Duarte, A.P.; Ribeiro, M.H.L.; Queiroz, J.A.; Domingues, F.C. Response surface optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis of cistus ladanifer and cytisus striatus for bioethanol production. Biochem. Eng. J 2009, 45, 192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Eijsink, V.G.H.; Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Vårum, K.M.; Horn, S.J. Towards new enzymes for biofuels: Lessons from chitinase research. Trends Biotechnol 2008, 26, 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Mojović, L.; Nikolić, S.; Rakin, M.; Vukasinović, M. Production of bioethanol from corn meal hydrolyzates. Fuel 2006, 85, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar]

- Piskur, J.; Rozpedowska, E.; Polakova, S.; Merico, A.; Compagno, C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet 2006, 22, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Alper1, H.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering for biofuels: Exploiting innate microbial capacity or importing biosynthetic potential? Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2009, 7, 715–723. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Smith, J.A.; Oi, F.M.; Koehler, P.G.; Bennett, G.W.; Scharf, M.E. Correlation of cellulase gene expression and cellulolytic activity throughout the gut of the termite Reticulitermes flavipes. Gene 2007, 395, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Geib, S.M.; Tien, M.; Hoover, K. Identification of proteins involved in lignocellulose degradation using in gel zymogram analysis combined with mass spectroscopy-based peptide analysis of gut proteins from larval asian longhorned beetles, Anoplophora glabripennis. Insect Sci 2010, 17, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, A.H.; Marana, S.R.; Terra, W.R.; Ferreira, C. Purification, molecular cloning, and properties of a beta-glycosidase isolated from midgut lumen of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera) larvae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 2001, 31, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Cazemier, A.E.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Hackstein, J.H.P.; Vogels, G.D. Fibre digestion in arthropods. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol 1997, 118, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brune, A. Termite guts: The world’s smallest bioreactors. Trends Biotechnol 1998, 16, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Breznak, J.A.; Brune, A. Role of microorganisms in the digestion of lignocellulose by termites. Annu. Rev. Entomol 1994, 39, 453–487. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M.; Schonig, I.; Berchtold, M.; Kampfer, P.; Konig, H. Aerobic and facultatively anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria from the gut of the termite Zootermopsis angusticollis. J. Appl. Microbiol 2002, 92, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, H.; Tokuda, G. Cellulolytic systems in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2010, 55, 609–632. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, N.; Sarkar, G.M.; Lahiri, S.C. Cellulose degrading capabilities of cellulolytic bacteria isolated from the intestinal fluids of the silver cricket. Environmentalist 2000, 20, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.M.; Doran-Peterson, J. Mining diversity of the natural biorefinery housed within Tipula abdominalis larvae for use in an industrial biorefinery for production of lignocellulosic ethanol. Insect Sci 2010, 17, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Delalibera, I.; Handelsman, J.; Raffa, K.F. Contrasts in cellulolytic activities of gut microorganisms between the wood borer, Saperda vestita (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the bark beetles, Ips pini and Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Entomol 2005, 34, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Cazemier, A.E.; Verdoes, J.C.; Reubsaet, F.A.; Hackstein, J.H.; van der Drift, C.; Op den Camp, H.J. Promicromonospora pachnodae sp. nov., a member of the (hemi)cellulolytic hindgut flora of larvae of the scarab beetle Pachnoda marginata. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2003, 83, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Marshall, S.; Jackson, T.A. The scarab gut: A potential bioreactor for bio-fuel production. Insect Sci 2010, 17, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, P.; Bignell, D.; Lepage, M.; Wolters, V.; Roger, P.; Ineson, P.; Heal, O.W.; Dhillion, S. Soil function in a changing world: The role of invertebrate ecosystem engineers. Eur. J. Soil Biol 1997, 33, 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cazemier, A.E.; Hackstein, J.H.P.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Rosenberg, J.; van der Drift, C. Bacteria in the intestinal tract of different species of arthropods. Microb. Ecol 1997, 33, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Jackson, T.A. Autochthonous bacterial flora indicated by PCR-DGGE of 16S rRNA gene fragments from the alimentary tract of Costelytra zealandica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). J. Appl. Microbiol 2008, 105, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Bayon, C.; Mathelin, J. Carbohydrate fermentation and by-product absorption studied with labeled cellulose in Oryctes nasicornis larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). J. Insect Physiol 1980, 26, 833–840. [Google Scholar]

- Geissinger, O.; Herlemann, D.P.R.; Mörschel, E.; Maier, U.G.; Brune, A. The ultramicrobacterium “Elusimicrobium minutum” gen. nov., sp. nov., the first cultivated representative of the termite group 1 phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2009, 75, 2831–2840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.M.; Ju, Q.; Qu, M.J.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Dong, S.L.; Han, Z.J.; Yu, S.L. EAG and behavioral responses of the large black chafer, Holotrichia parallela (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) to its sex pheromone. Acta Entomol. Sin 2009, 52, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Egert, M.; Wagner, B.; Lemke, T.; Brune, A.; Friedrich, M.W. Microbial community structure in midgut and hindgut of the humus-feeding larva of Pachnoda ephippiata (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2003, 69, 6659–6668. [Google Scholar]

- Egert, M.; Stingl, U.; Bruun, D.L.; Wagner, B.; Brune, A.; Friedrich, M.W. Structure and topology of microbial communities in the major gut compartments of Melolontha melolontha larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2005, 71, 4556–4566. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, T.; Stingl, U.; Egert, M.; Friedrich, M.W.; Brune, A. Physicochemical conditions and microbial activities in the highly alkaline gut of the humus-feeding larva of Pachnoda ephippiata (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2003, 69, 6650–6658. [Google Scholar]

- Talia, P.; Sede, S.M.; Campos, E.; Rorig, M.; Principi, D.; Tosto, D.; Hopp, H.E.; Grasso, D.; Cataldi, A. Biodiversity characterization of cellulolytic bacteria present on native Chaco soil by comparison of ribosomal RNA genes. Res. Microbiol 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleroni, N.J. The Pseudomonas story. Environ. Microbiol 2010, 12, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Brodey, C.L.; Rainey, P.B.; Tester, M.; Johnstone, K. Bacterial blotch disease of the cultivated mushroom is caused by an ion channel forming lipodepsipeptide toxin. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 1991, 4, 407–411. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.M. Drippy gill: A bacterial disease of cultivated mushrooms caused by Pseudomonas agarici n. sp. N. Z. J. Agric. Res 1970, 13, 977–990. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, K.; Kimura, K.; Komagata, K. Two new species of Pseudomonas: P. oryzihabitans isolated from rice paddy and clinical specimens and P. Luteola isolated from clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 1985, 35, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, M.; Poffe, R.; Verachtert, H. Properties of a cellulolytic Pseudomonas. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1984, 50, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, S.S.; Dadarwal, K.R. Chitinolytic and cellulolytic Pseudomonas sp. Antagonistic to fungal pathogens enhances nodulation by Mesorhizobium sp. Cicer in chickpea. Microbiol. Res 2001, 156, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Millward-Sadler, S.J.; Davidson, K.; Hazlewood, G.P.; Black, G.W.; Gilbert, H.J.; Clarke, J.H. Novel cellulose-binding domains, NodB homologues and conserved modular architecture in xylanases from the aerobic soil bacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens subsp. cellulosa and Cellvibrio mixtus. Biochem. J 1995, 312, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- van Dyk, J.S.; Sakka, M.; Sakka, K.; Pletschke, B.I. The cellulolytic and hemi-cellulolytic system of Bacillus licheniformis SVD1 and the evidence for production of a large multi-enzyme complex. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2009, 45, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Chelius, M.K.; Triplett, E.W. Dyadobacter fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel gram-negative bacterium isolated from surface-sterilized Zea mays stems. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2000, 50, 751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, E.; Lapidus, A.; Chertkov, O.; Brettin, T.; Detter, J.C.; Han, C.; Copeland, A.; Glavina Del Rio, T.; Nolan, M.; Chen, F.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Dyadobacter fermentans type strain (NS114T). Stand. Genomic Sci 2009, 1, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, C.; Okeke, B.C.; Lu, J. Characterization of a defined cellulolytic and xylanolytic bacterial consortium for bioprocessing of cellulose and hemicelluloses. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 2011, 163, 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- Clermont, D.; Diard, S.; Bouchier, C.; Vivier, C.; Bimet, F.; Motreff, L.; Welker, M.; Kallow, W.; Bizet, C. Microbacterium binotii sp. nov., isolated from human blood. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2009, 59, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo, M.; Jiménez-Zurdo, J.I.; Velázquez, E.; Trujillo, M.E.; Zurdo-Piñeiro, J.L.; Ramírez-Bahena, M.H.; Ramos, B.; Díaz-Mínguez, J.M.; Dazzo, F.; Martínez-Molina, E.; et al. Rhizobium cellulase CelC2 is essential for primary symbiotic infection of legume host roots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7064–7069. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, P.F.; Jimenez-Zurdo, J.I.; Chen, J.; Squartini, A.S.; Haack, S.K.; Martinez-Molina, E.; Hubbell, D.H.; Dazzo, F.B. Cell-associated pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzymes in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1992, 58, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, O.; Lodhi, A.; Brandelet, G.; Santaella, C.; Roncato, M-A.; Christen, R.; Heulin, T.; Achouak, W. Rhizobium alamii sp. nov., an exopolysaccharide-producing species isolated from legume and non-legume rhizospheres. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2009, 59, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Germida, J.J. Growth of indigenous Rhizobium leguminosarum and Rhizobium meliloti in soils amended with organic nutrients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1988, 54, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.W.; Setubal, J.C.; Kaul, R.; Monks, D.E.; Kitajima, J.P.; Okura, V.K.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Wood, G.E.; Almeida, N.F., Jr; et al. Science 2001, 294, 2317–2323.

- Han, J-I.; Choi, H-K.; Lee, S-W.; Orwin, P.M.; Kim, J.; LaRoe, S.L.; Kim, T-G.; O’Neil, J.; Leadbetter, J.R.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the metabolically versatile plant growth-promoting endophyte Variovorax paradoxus S110. J. Bacteriol 2011, 193, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.D.; Song, Y.B.; Wang, Y.J.; Gao, Y.M.; Jing, R.Y.; Cui, Z.J. Biodiversity of mesophilic microbial community BYND-8 capability of lignocellulose degradation and its effect on biogas production. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2011, 32, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Teather, R.M.; Wood, P.J. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1982, 43, 777–780. [Google Scholar]

- Heuer, H.; Krsek, M.; Baker, P.; Smalla, K.; Wellington, E.M. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1997, 63, 3233–3241. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Murcia, A.J.; Acinas, S.G.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Evaluation of prokaryotic diversity by restrictase digestion of 16S rDNA directly amplified from hypersaline environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 1995, 17, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti, C.J.; Neto, E.D.; Simpson, A.J. Rapid silver staining and recovery of PCR products separated on polyacrylamide gels. Biotechniques 1994, 17, 914–921. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov accessed on 2 December 2011.

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Cardenas, E.; Fish, J.; Chai, B.; Farris, R.J.; Kulam-Syed-Mohideen, A.S.; McGarrell, D.M.; Marsh, T.; Garrity, G.M.; et al. The ribosomal database project: Improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D141–D145. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, J.; Lee, J-H.; Jung, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, B.K.; Lim, Y-W. Eztaxon: A web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2007, 57, 2259–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Smibert, R.M.; Krieg, N.R. Phenotypic Characterization. In Methods for General and Molecular Bacteriology; Gerhardt, P., Murray, R.G.E., Wood, W.A., Krieg, N.R., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 607–654. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Representative strains | Phylum/class | Identities of isolates | Numbers of Strains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium II | Medium III | ||||

| 1 | H16 | Firmicutes | Bacillus licheniformis | 6 | 3 |

| 2 | H212 | Bacteroidetes | Dyadobacter fermentans | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | H59 | Siphonobacter aquaeclarae | 0 | 1 | |

| 4 | H99 | Actinobacteria | Cellulosimicrobium funkei | 16 | 12 |

| 5 | H97 | Microbacterium oxydans | 1 | 1 | |

| 6 | H63 | Microbacterium binotii | 5 | 4 | |

| 7 | H1 | Microbacterium pumilum | 2 | 9 | |

| 8 | H122 | α-Proteobacteria | Paracoccus sulfuroxidans | 3 | 0 |

| 9 | H108 | Ochrobactrum lupini | 1 | 0 | |

| 10 | H191 | Ochrobactrum cytisi | 10 | 12 | |

| 11 | H70 | Ochrobactrum haematophilum | 2 | 0 | |

| 12 | H87 | Rhizobium radiobacter | 18 | 6 | |

| 13 | H6 | Kaistia adipata | 0 | 2 | |

| 14 | H162 | Devosia riboflavina | 0 | 1 | |

| 15 | H37 | Labrys neptuniae | 1 | 1 | |

| 16 | H75 | Ensifer adhaerens | 2 | 0 | |

| 17 | H173 | β-Proteobacteria | Variovorax paradoxus | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | H19 | Shinella zoogloeoides | 0 | 1 | |

| 19 | H143 | γ-Proteobacteria | Citrobacter freundii | 5 | 0 |

| 20 | H45 | Pseudomonas nitroreducens | 40 | 25 | |

| 21 | H72 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 11 | 3 | |

| Characteristic | Representative Strains | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H16 | H212 | H59 | H97 | H99 | H63 | H1 | H122 | H108 | H191 | H87 | H6 | H162 | H37 | H70 | H75 | H173 | H19 | H143 | H45 | H72 | |

| Gram strain | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Motility | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Catalase | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oxidase | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| MR test | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| V-P test | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Indole test | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Nitrate reduction | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| Urease | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Hydrolysis of | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Gelatin | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Acid produced from glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Gas produced from glucose | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Arginine dihydrolase | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Assimilation of | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Citrate | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Fructose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lactose | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Maltose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Mannose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Mannitol | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Rhamnose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Xylose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Sorbitol | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

© 2012 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, S.; Sheng, P.; Zhang, H. Isolation and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria from the Gut of Holotrichia parallela Larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 2563-2577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13032563

Huang S, Sheng P, Zhang H. Isolation and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria from the Gut of Holotrichia parallela Larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012; 13(3):2563-2577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13032563

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Shengwei, Ping Sheng, and Hongyu Zhang. 2012. "Isolation and Identification of Cellulolytic Bacteria from the Gut of Holotrichia parallela Larvae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13, no. 3: 2563-2577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13032563