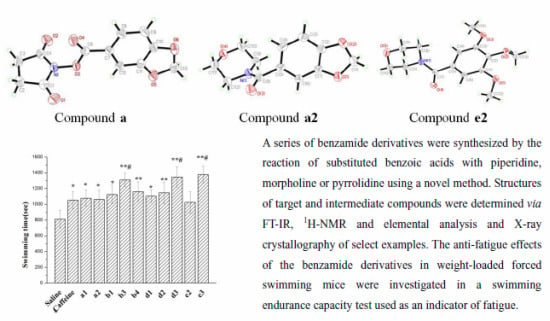

Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Some Benzamide Derivatives

Abstract

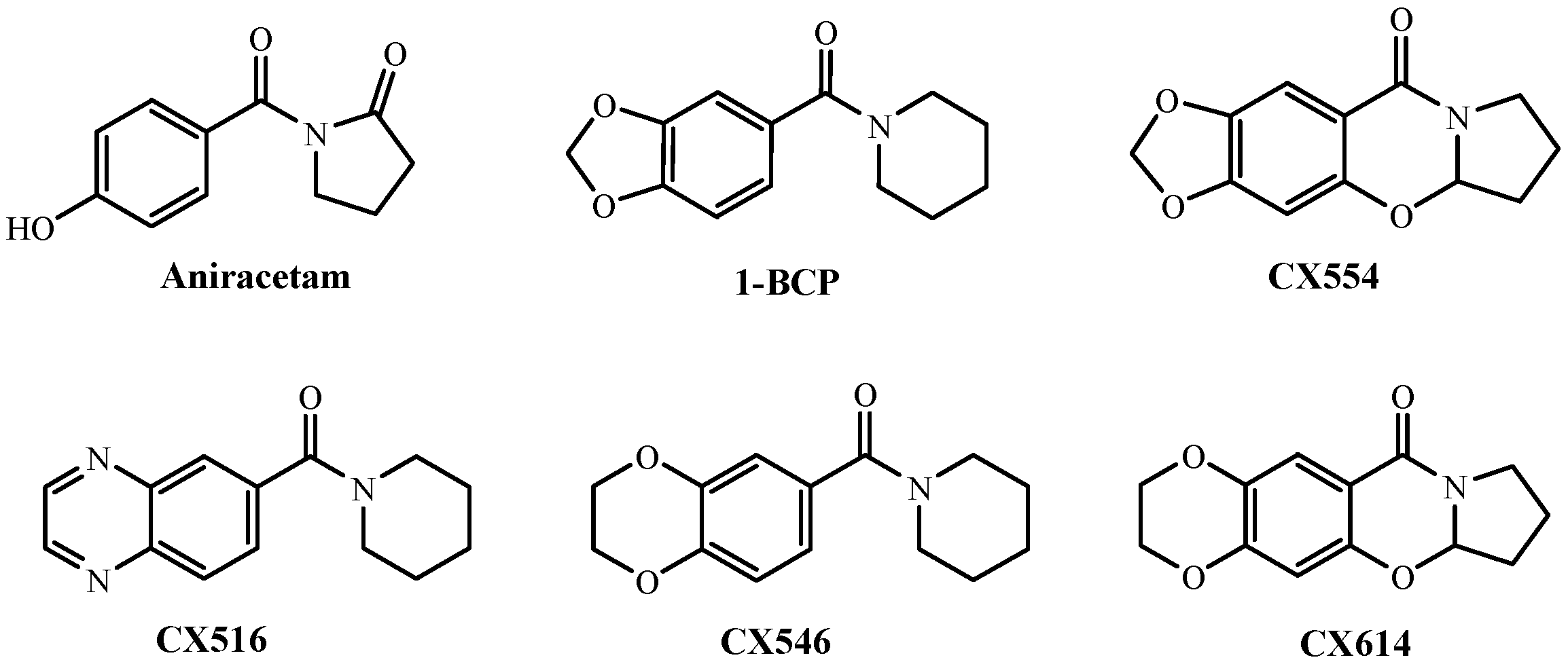

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

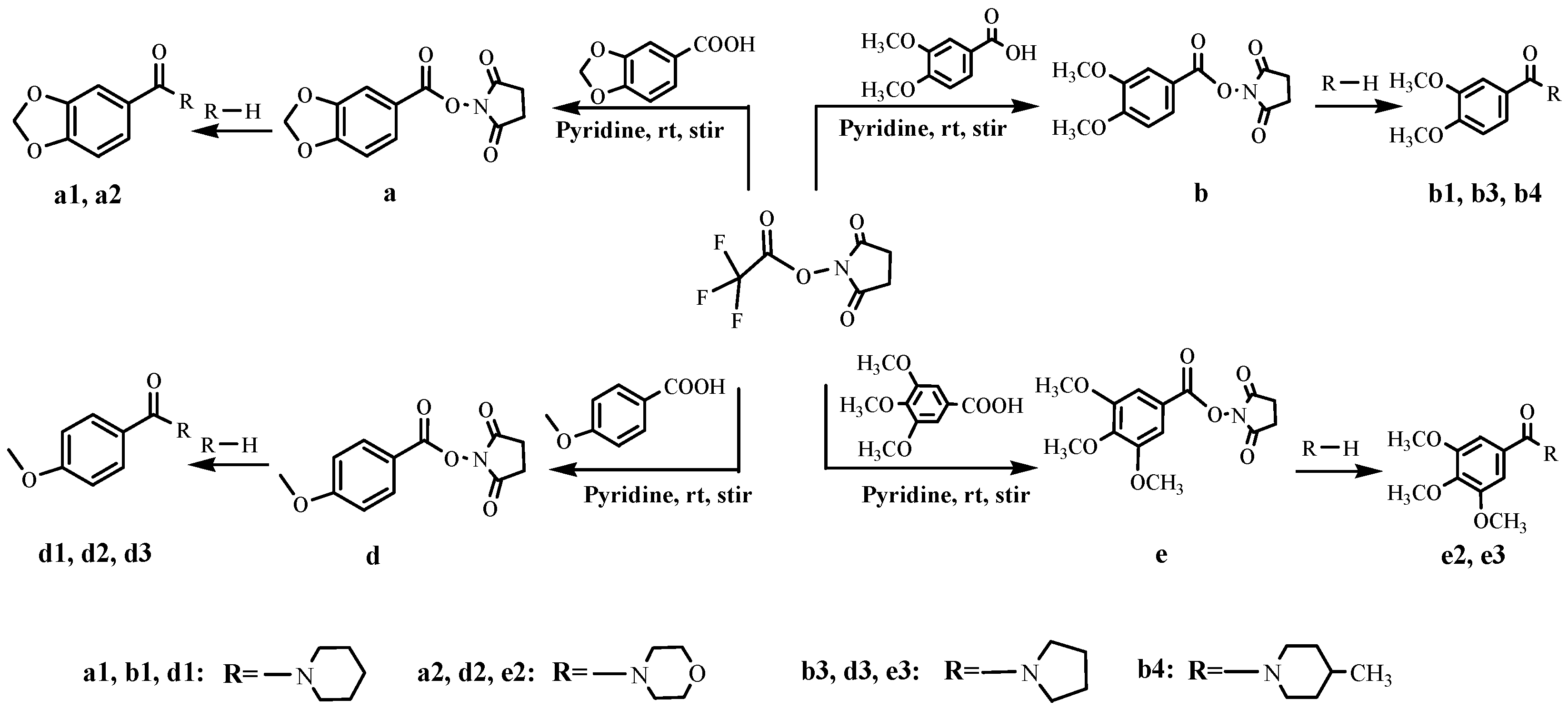

2.1. Synthesis and Structural Confirmation

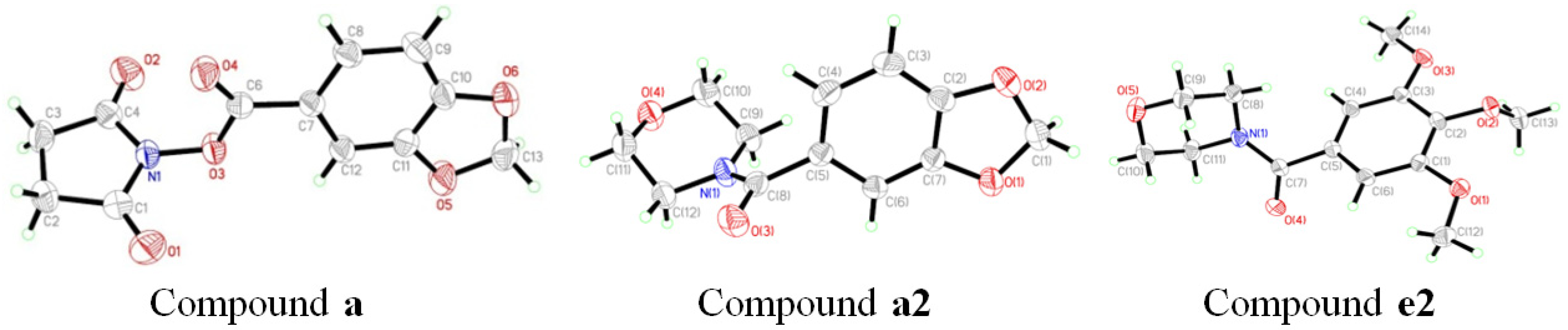

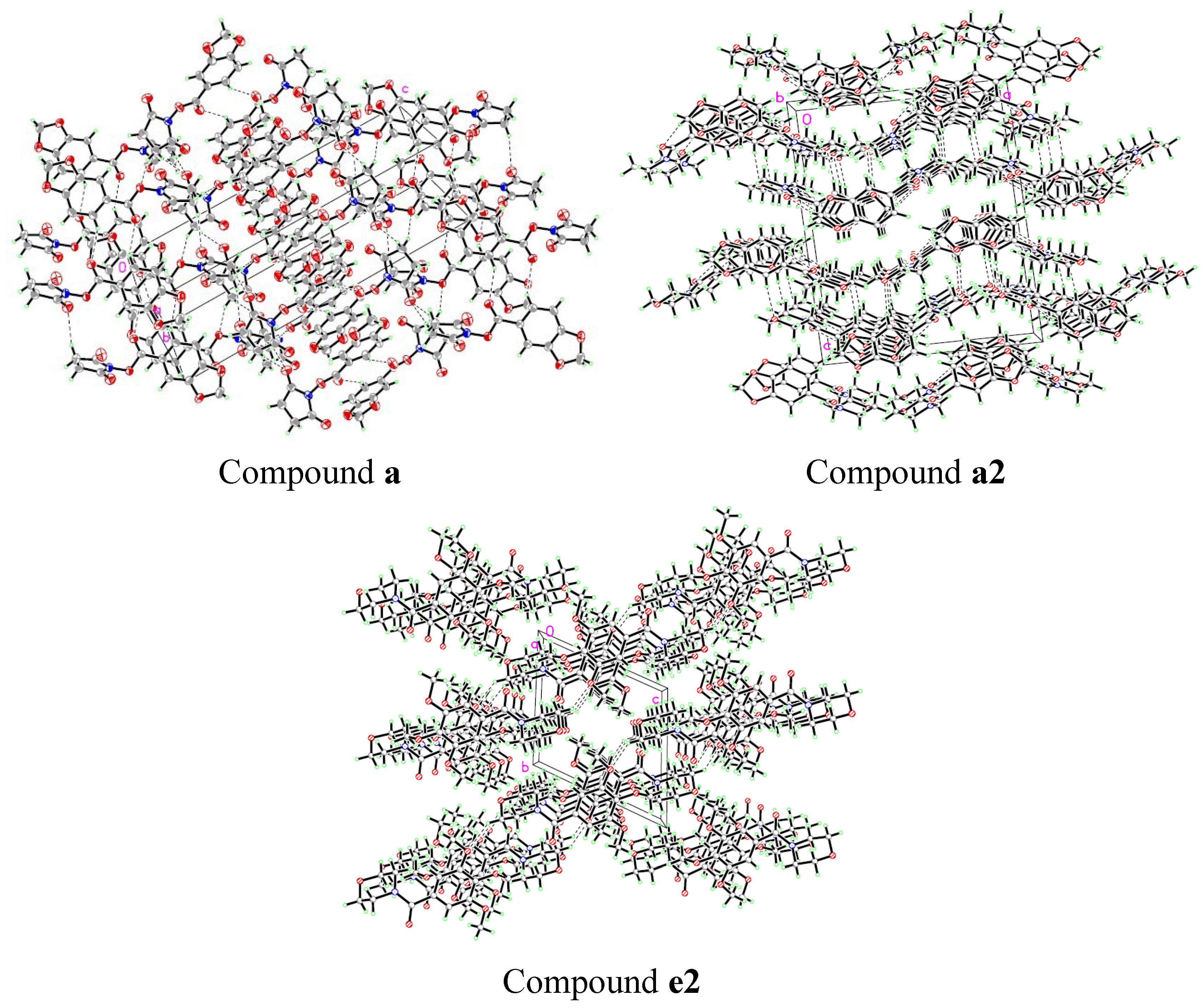

2.2. Crystal Structures

| a | a2 | e2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCDC Deposit No. | 815292 | 960811 | 960813 |

| Empirical formula | C12H9NO6 | C12H13NO4 | C14H19NO5 |

| Formula weight | 263.20 | 235.23 | 281.30 |

| Temperature (K) | 296(2) | 296(2) | 296 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic | Triclinic |

| Space group | P2(1)/n | P bca | P-1 |

| a (Å) | 8.7694(11) | 14.595(3) | 8.6577(9) |

| b (Å) | 6.2631(8) | 7.7849(14) | 9.5460(10) |

| c (Å) | 22.168(3) | 20.112(4) | 9.8578(10) |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 | 64.1760(10) |

| β (°) | 94.814(2) | 90 | 77.037(2) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 90 | 71.6540(10) |

| Volume (Å3) | 1213.3(3) | 2285.1(7) | 692.44(12) |

| Z | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Dcalc (g/cm3) | 1.441 | 1.368 | 1.349 |

| Abs.coefficient (mm−1) | 0.118 | 0.104 | 0.096 |

| F(000) | 544 | 992 | 300 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.14 × 0.11 × 0.10 | 0.20 × 0.10 × 0.10 | 0.39 × 0.27 × 0.20 |

| θ limit (°) | 1.84 to 25.10 | 2.46 to 25.00 | 2.31 to 25.00 |

| Ranges/indices h. k. l. | −10/10, −7/6, −26/26 | −15/17, −9/9, −23/17 | −9/10, −9/11, −11/11 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | ||

| Reflections collected/ unique/Rint | 5777 / 2165/ 0.043 | 10446/2001/0.033 | 3490/ 2432/0.0205 |

| Completeness to θ = 25.10° | 99.6% | 99.6% | 99.3% |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2165/0/173 | 2001/0/155 | 2432/0/185 |

| Goodness of fit on F2 | 1.088 | 1.023 | 1.085 |

| R1, wR2 | 0.0456, 0.1199 | 0.0589, 0.1553 | 0.0404, 0.1261 |

| Extinction coefficient | 0.020(4) | 0.0028(11) | 0.120(12) |

| Largest diff. peak and hole(e. Å −3) | 0.149 and −0.161 | 0.489 and −0.219 | 0.155 and −0.186 |

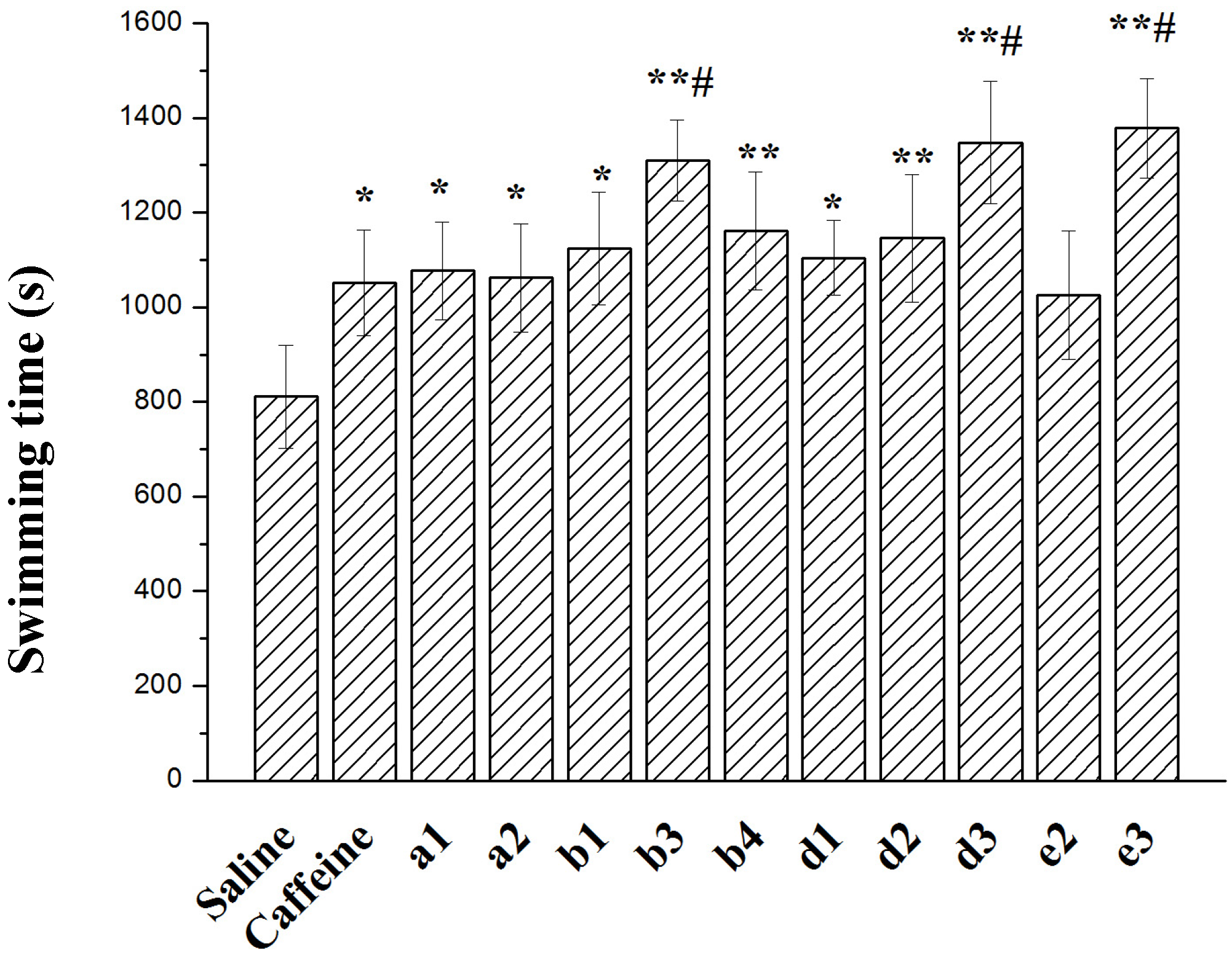

2.3. Effect on Forced Swimming Capacity

3. Experimental

3.1. General Information

3.2. Synthesis

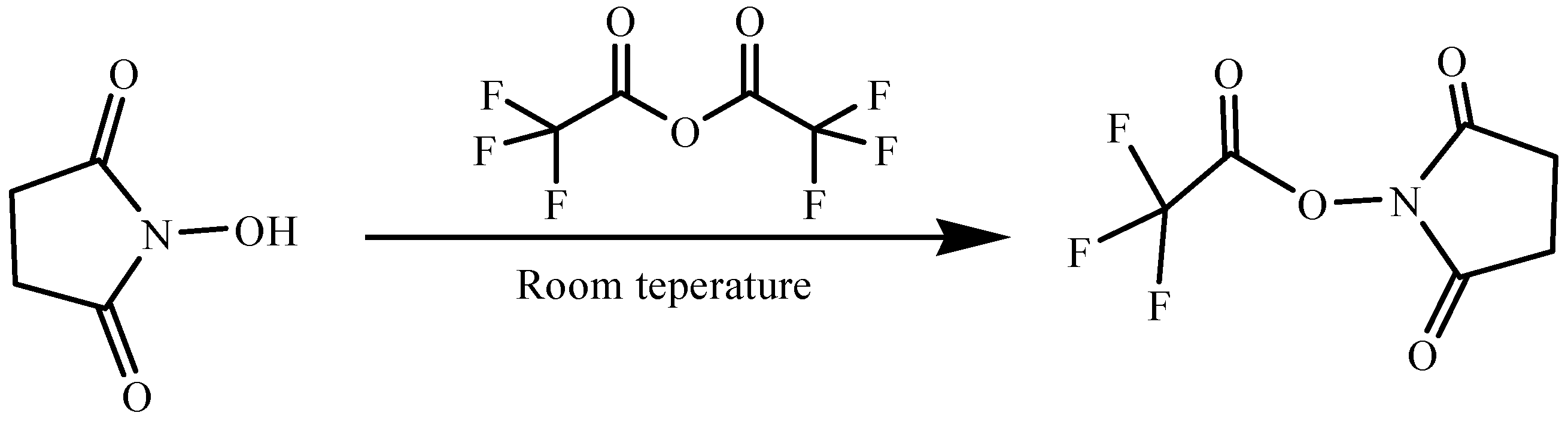

3.2.1. Preparation of N-Hydroxysuccinimidyl Trifluoroacetate (NHS-TFA)

3.2.2. Synthesis of 3-Benzodioxole-5-carboxylic acid, 2,5-dioxo-1-pyrrolidinyl Ester (a)

3.2.3. Synthesis of 3,4-Dimethoxybenzoic acid, 2,5-dioxo-1-pyrrolidinyl ester (b)

3.2.4. Synthesis of 4-Methoxybenzoic acid, 2,5-dioxo-1-pyrrolidinyl ester (d)

3.2.5. Synthesis of 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzoic acid, 2,5-dioxo-1-pyrrolidinyl Ester (e)

3.2.6. Synthesis of Compounds a1 and a2

3.2.7. Synthesis of Compounds b1, b3 and b4

3.2.8. Synthesis of Compound d1–d3

3.2.9. Synthesis of Compounds e2 and e3

3.3. Anti-Fatigue Activity Assessment of Benzamide Derivatives

3.3.1. Animals

3.3.2. Anti-Fatigue Activity

3.3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Black, M.D. Psychopharmacology of glutamate-therapeutic potential of positive AMPA modulators. Psychopharmacology 2005, 179, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomeli, H.; Mosbacher, J.; Melcher, T.; Hoger, T.; Kuner, T.; Monyer, H.; Higuchi, M.; Bach, A.; Seeburg, P.H. Control of kinetic properties of AMPA receptor channels by nuclear RNA editing. Science 1994, 266, 1709–1713. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, B.; Keinanen, K.; Verdoorn, T.A.; Wisden, W.; Burnashev, N.; Herb, A.; Kohler, M.; Takagi, T.; Sakmann, B.; Seeburg, P.H. Flip and flop: A cell-specific functional switch in glutamate-operated channels of the CNS. Science 1990, 249, 1580–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Arai, A.; Kessler, M.; Xiao, P.; Ambros-Ingerson, J.; Rogers, G.; Lynch, G. A centrally active drug that modulates AMPA receptor gated currents. Brain Res. 1994, 638, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.A. AMPA receptor activation potentiated by the AMPA modulator 1-BCP is toxic to cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 249, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, I.; Tanabe, S.; Kohda, A.; Sugiyama, H. Allosteric potentiation of quisqualate receptors by nootropic drug aniracetam. J. Physiol. 1990, 424, 533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, M.; Arai, A.C. Use of [3H] fluorowillardiine to study properties of AMPA receptor allosteric modulators. Brain Res. 2006, 1076, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, G.R.; McCulloch, J.; Shahid, M.; Hill, D.R.; Henry, B.; Horsburgh, K. Regionally selective and dose-dependent effects of the ampakines Org 26576 and Org 24448 on local cerebral glucose utilisation in the mouse as assessed by 14C-2-deoxyglucose autoradiography. Neuropharmacology 2005, 49, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Luu, N.T.; Herbst, T.A.; Knapp, R.; Lutz, D.; Arai, A.; Lynch, G. Synergistic interactions between ampakines and antipsychotic drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 289, 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, B.A.; Bendiske, J.; Brown, Q.B.; Munirathinam, S.; Caba, E.; Rudin, M.; Urwyler, S.; Sauter, A.; Rogers, G. Survival signaling and selective neuroprotection through glutamatergic transmission. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 174, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterborn, J.C.; Truong, G.S.; Baudry, M.; Bi, X.; Lynch, G.; Gall, C.M. Chronic elevation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor by ampakines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.D.; Zeng, X.H.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Pan, Z.Q.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.B. Silica gel-mediated amide bond formation: An environmentally benign method for liquid-phase synthesis and cytotoxic activities of amides. J. Comb. Chem. 2010, 12, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagoe, Y.; Moriyama, K.; Togo, H. Facile preparation of amides from carboxylic acids and amines with ion-supported Ph3P. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3971–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, G.S.; Lim, J.K.; Woo, W.S. Synthesis and central nervous depressant activities of piperdine derivatives. Yakhak. Hoechi. 1986, 30, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Naota, T.; Murahashi, S.-I. Ruthenium-catalyzed transformations of amino alcohols to lactams. Synlett 1991, 10, 693–694. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.F.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Selective palladium-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of aryl halides with CO and ammonia to primary amides. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9750–9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, L.; Granito, C.; Rosato, F.; Videtta, V. One-pot amide synthesis from allyl or benzyl halides and amines by Pd-catalysed carbonylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.L.; Fan, W.T.; Kong, X.H.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Mei, Q.B. Process for the preparation of benzodioxolecarboxamide and benzodioxancarboxamide derivatives. CN 102276576 A 20111214, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXS-97, Program for Solution Crystal Structure; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL-97, Program for Solution Crystal Structure and Refinement; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stereochemical Workstation Operation Manual, Release 3.4, Siemens Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1989.

- Lavrov, M.I.; Lapteva, V.L.; Grigor’ev, V.V.; Palyulin, V.A.; Bachurin, S.O.; Zefirov, N.S. Synthesis and AMPA-receptor modulating activity of benzodioxanecarboxylic and piperonylic acid derivatives. Pharm. Chem. J. 2012, 46, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse, R.; Ramirez, C.; Muchowski, J.M. Synthesis of alkylpyrroles by the sodium borohydride reduction of acylpyrroles. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 2961–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, B.; Ohlan, S.; Ohlan, R.; Judge, V.; Narang, R. Hansch analysis of veratric acid derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Lin, S.; Liang, F.; Liu, P. Copper-catalyzed aerobic oxidative synthesis of α-ketoamides from methyl ketones, amines and NIS at room temperature. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 9237–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q. Heterobimetallic lanthanide/sodium phenoxides: Efficient catalysts for amidation of aldehydes with amines. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2575–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargha, L.; Kasztreiner, E.; Borsy, J.; Farkas, L.; Kuszmann, J.; Dumbovich, B. Synthesis and pharmacological investigation of new alkoxybenzamides—I: 3, 4, 5-Trimethoxybenzamides. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1962, 11, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.A.; Han, D.; Kwon, E.K.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, Y.E. Antifatigue effect of rubus coreanus miquel extract in mice. J. Med. Food 2007, 10, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.M.; Wu, C.F. Antifatigue activity of tissue culture extracts of saussurea involucrata. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selsby, J.T.; Beckett, K.D.; Kern, M. Swim performance following creatine supplementation in division III athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2003, 17, 421–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.; Kim, I.H.; Han, D. Effect of medicinal plant extracts on forced swimming capacity in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 93, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Fan, W.; Pan, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, C.; Mei, Q. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Some Benzamide Derivatives. Molecules 2014, 19, 1034-1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19011034

Wu X, Fan W, Pan Y, Zhai Y, Niu Y, Li C, Mei Q. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Some Benzamide Derivatives. Molecules. 2014; 19(1):1034-1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19011034

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xianglong, Wutu Fan, Yalei Pan, Yuankun Zhai, Yinbo Niu, Chenrui Li, and Qibing Mei. 2014. "Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Some Benzamide Derivatives" Molecules 19, no. 1: 1034-1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19011034

APA StyleWu, X., Fan, W., Pan, Y., Zhai, Y., Niu, Y., Li, C., & Mei, Q. (2014). Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Some Benzamide Derivatives. Molecules, 19(1), 1034-1046. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19011034