1. Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), defined as infections that occur during patient care, result in avoidable deaths or prolonged hospitalization for millions of people worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. HAIs increase healthcare costs and contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant infections [

1,

4]. Hence, preventing HAI is an important strategic intervention for patients’ safety and the quality of health care [

5]. Hand hygiene is the single most important strategy for reducing the spread of HAI and antimicrobial-resistant pathogens [

6,

7,

8].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified hand hygiene as the core indicator of patients’ safety. In 2010, WHO recommended the hand hygiene self-assessment framework (HHSAF) tool to assess the progress of healthcare facilities in hand hygiene promotion and practices [

9]. Many hospitals in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have implemented the HHSAF tool, identified gaps, and developed actions for improvements [

8].

Sierra Leone, a low-income country on the West Coast of Africa, established its first national policy on infection prevention and control (IPC) practices following the adversity of the largest Ebola outbreak to date during 2014–2016 [

10,

11]. Sierra Leone has been collecting data annually to assess hospitals’ compliance with hand hygiene practices and promotion using the WHO HHSAF tool.

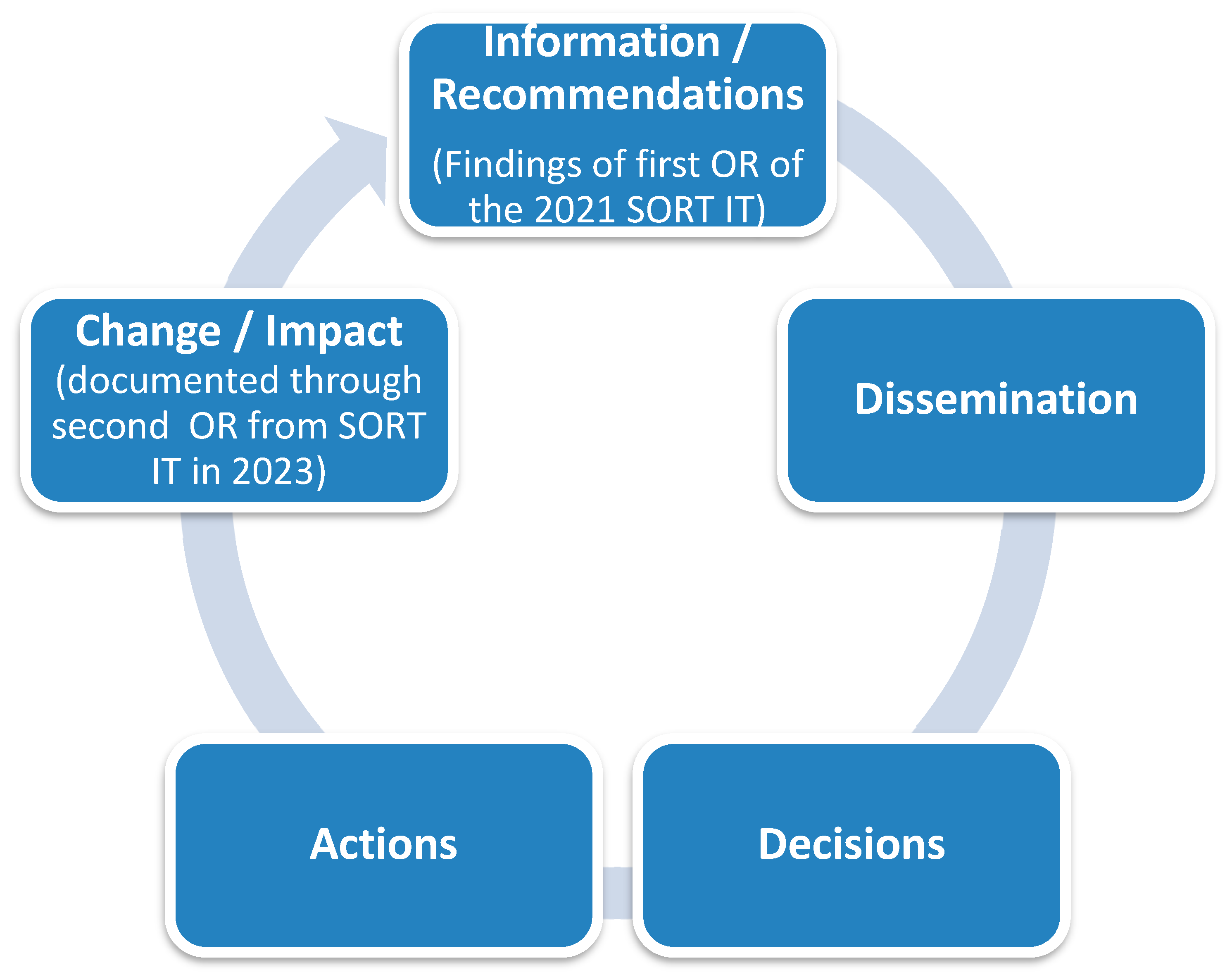

In 2021, the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) based at WHO (Geneva) led a Sierra Leone national Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT) course focusing on antimicrobial resistance [

12]. Through this course, we conducted an operational research study in 13 public hospitals in the Western Area of Sierra Leone using the HHSAF tool [

13]. We observed an “intermediate” level of hand hygiene promotion and practice (HHSAF score 251–375) and challenges such as the lack of dedicated budgets to support hand hygiene activities and a formalized patient engagement strategy [

13]. Following this operational research, a hand hygiene improvement initiative was launched in 2022. This included engagement of stakeholders at the national and hospital levels, actions to formalize patient engagement, and systematic audits of hand hygiene promotion resources.

In this first-of-its-kind study from Sierra Leone, we aimed to describe the changes in hand hygiene practice and promotion in 13 public hospitals in the Western Area of Sierra Leone following the implementation of recommendations from the previous operational research [

13]. Specifically, among the 13 public hospitals in the Western Area of Sierra Leone, before (May 2021) and after (April 2023) the implementation of the recommendations from an operational research project, we described the changes in (i) compliance with hand hygiene practice and promotion, overall and stratified by hospital type and domains (systems change, training and education, evaluation and feedback, reminders in the workplace, and institutional safety climate) and (ii) performance against each indicator under the various domains of the HHSAF tool.

4. Discussion

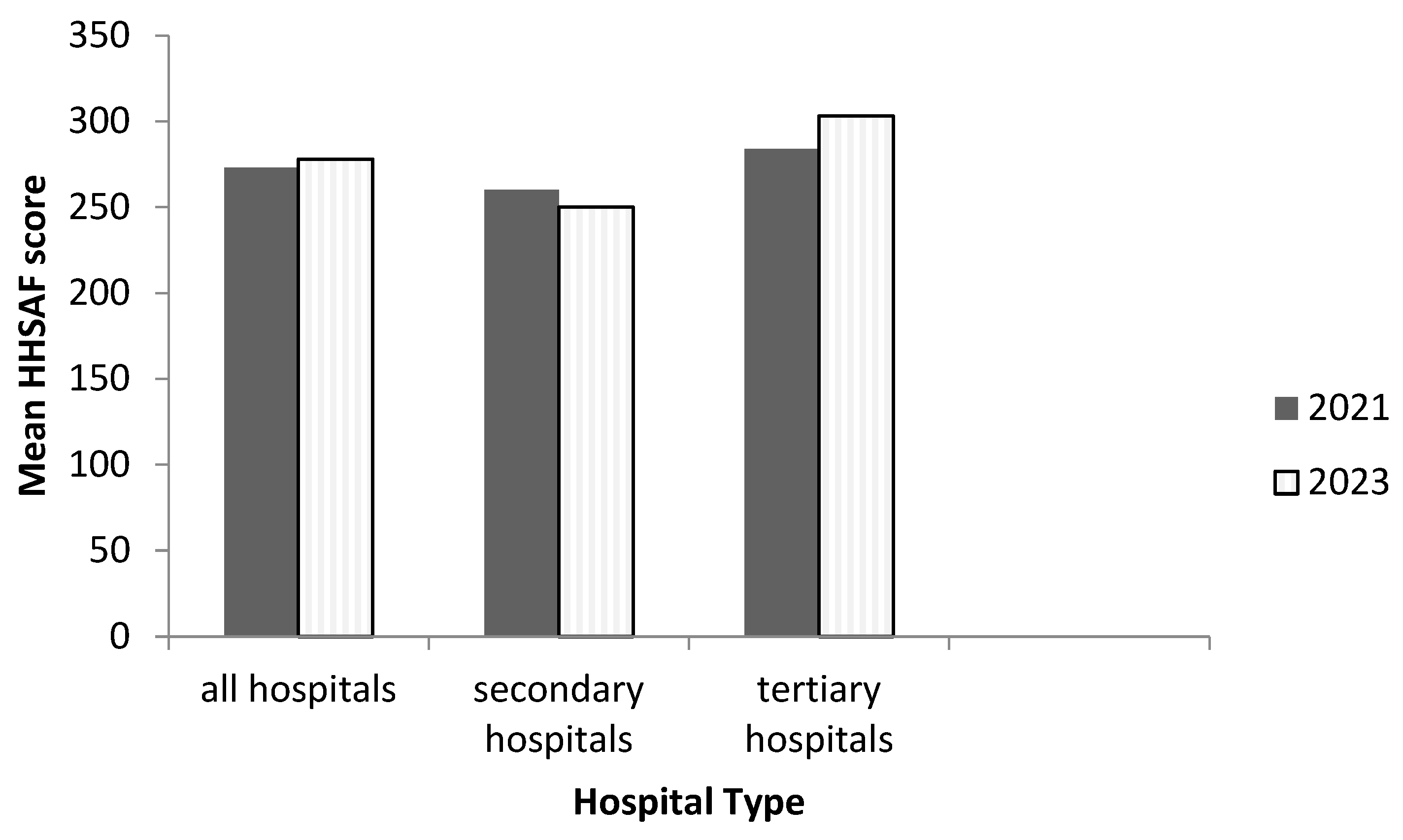

In this assessment of changes in hand hygiene practices and promotion in the Western Area of Sierra Leone following the implementation of recommendations from an operational research study, we found that the overall HHSAF score and level did not change across hospitals. While an improvement was observed in the mean score of tertiary hospitals, the level remained the same (“intermediate or consolidation”). In secondary hospitals, hand hygiene practices and promotion deteriorated from an “intermediate or consolidation” to a “basic” level. Furthermore, we observed an improvement in the performance of the “system change” and “institutional safety climate” domains but a deterioration in the performance of the “training and education” and “reminders in the workplace” domains.

Our study has strengths and limitations. To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence of changes in hand hygiene practices before (May 2021) and after (April 2023) the implementation of the recommendations of an operational research study, and its findings have important policy implications for improving hand hygiene practice and promotion in Sierra Leone and the wider world.

One of the limitations is that the HHSAF tool used in this study was not adapted to our local context, and, in the absence of adequate training, its indicators may be interpreted differently in routine practice. However, we overcame this through training and closely reviewing on a daily basis the data collected with the IPC focal persons. Going forward, we recommend the development of an annex document indicating the correct interpretation of this tool.

Second, we inferred changes based on public health significance, particularly if the HHSAF level changes. However, due to the small sample size (n = 13 hospitals), it was not appropriate to use statistical tests to assess the statistical significance of the differences.

The study has three key findings, which we discuss below.

First, the overall HHSAF score and level did not change across hospitals. There are many barriers to the successful implementation of hand hygiene promotion and practice in LMICs, including a lack of resources to implement hand hygiene [

19,

20,

21]. These barriers may have contributed to the lower mean hand hygiene scores reported in Sierra Leone and other LMICs and reflect the need to support these countries in strengthening their hand hygiene practices and promotion.

In our setting, challenges such as a lack of dedicated budgets to support hand hygiene activities and a formalized patient engagement strategy were observed in May 2021 [

12]. As alluded to earlier, we tried to address these gaps by introducing a hand hygiene improvement initiative in 2022 that included initial meetings with stakeholders at national and hospital levels. However, due to limited funding, follow-up meetings with stakeholders, including the hospital’s IPC leadership, were not held. Consequently, though patient engagement in hand hygiene remains a novel practice, the situation in many hospitals has not improved. Between May 2021 and April 2023, many hospitals have undergone a series of infrastructure and system modifications. Some hospitals have expanded bed capacity without corresponding increases in staffing. This increase in the number of hospital beds and the corresponding reduction in the staff capacity in April 2023 may have also contributed to these gaps. Understaffing has been documented to be associated with low hand hygiene compliance [

22,

23,

24]. Moving forward, we plan to address these gaps by embedding a culture of quality and safety surrounding hand hygiene promotion in our hospitals. Again, we hope that the findings in this paper will act as a wake-up call for sustained implementation of hand hygiene improvement initiatives, including patient involvement in hand hygiene practices. Thus, we recommend the development of patient-friendly posters and other hand hygiene promotion resources in acute care settings to increase patient engagement in hand hygiene.

Second, in secondary hospitals, hand hygiene practice and promotion deteriorated from “intermediate or consolidation” to “basic” level. The decline may be partly due to infrastructure challenges (one hospital burned down and two were relocated due to ongoing renovations) or due to limited focus on post operational research interventions in secondary hospitals. Nonetheless, we observed that more secondary hospitals in April 2023 reported a continuous supply of alcohol-based hand rubs, and the number of hospitals with soap at each sink increased. Owing to the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, more resources were put together by the government and partner organizations to increase local production of alcohol-based hand rubs, reflecting the increase in the excellent performance of the system change domain in these hospitals. The mean “system change” domain score in April 2023 was higher than that observed for tertiary hospitals but performed poorly in all other domains. Therefore, we will advocate focusing on efforts to address the gaps observed in the poorly performing domains.

Third, we observed an improvement in performance in the “system change” and “institutional safety climate” domains, but the “training and education” and “reminders in the workplace” domains worsened. Gaps such as lack of a dedicated budget to train healthcare workers, lack of a system for the recognition and utilization of hand hygiene role models or hand hygiene champions, and the inability of most hospitals to provide hand hygiene promotion resources may have affected the performance of most domains. Although these challenges are not unique to Sierra Leone, as they have been reported in Cambodia, Rwanda, and Nigeria, they call for a robust approach to advocate for budgetary allocation to support hand hygiene activities and other IPC practices in the country [

21,

25,

26]. Furthermore, the low hand hygiene compliance rate reported in all the hospitals in May 2021 and April 2023 is a persistent and chronic problem affecting hand hygiene performance as low hand hygiene compliance rate has been previously reported in our hospitals [

19,

27].

Even though there is an improvement in the system change domain that could be attributed to the impact of COVID-19 on the development of hand hygiene infrastructure, we see a decline in other domains. The previous study was conducted in 2021; during this period, the incidence of COVID-19 cases was at its highest in Sierra Leone. Therefore, the hand hygiene scores were higher compared to our findings in 2023. For example, the training of healthcare workers and the availability of hand hygiene promotion posters declined in 2023. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on essential health service delivery is not unique to hand hygiene practices and promotion, as we have previously reported on the declines in HIV and TB services during the COVID-19 pandemic [

28,

29]. These facts underscore the importance of repeated assessment of hand hygiene practice and promotion at hospitals using an operational research approach to identify gaps in implementation, evaluate the sustainability of interventions, and use the evidence for action.

Despite the low mean HHSAF score reported in our study compared to that observed in the United States of America in 2011 (HHSAF score = 373), Greece in 2018 (HHSAF score = 289), and Italy in 2019 (HHSAF score = 332), the level remains at the same intermediate level (HHSAF Score 251–375) [

30,

31,

32]. Notably, the mean hand hygiene scores in LMICs such as Cambodia (HHSAF score = 177), India (HHSAF score = 225), and Tanzania (HHSAF score = 187) were lower than those we report in May 2021 and April 2023 [

21,

33,

34]. Sierra Leone experienced high-risk infectious disease epidemics such as the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak, which led to the establishment of IPC governance structures in the country [

10,

35]. This could explain Sierra Leone’s good performance in hand hygiene promotion relative to other LMICs.