2. The Ancestors as Anonymous Dead?

The demand for space within European cities has resulted in the extensive removal of historic (from the medieval period onwards) burial grounds to make way for new buildings or urban infrastructure. The majority of sites are excavated under heritage and archaeological legislation ensuring that at least some material evidence of burial practices is investigated. Despite the good survival of burial registers, it is often impossible to positively identify individual burials. Most have no coffin name plates and the spatial locations of burials were either rarely specifically recorded in documents or have been lost. Names, individual identities and family relationships become detached from materiality of the body, coffin, and grave space. The burial population generally stays unidentified and in this sense the recent time period of the graves matters little as they become as anonymous as a group of Neolithic or Roman burials. Archaeologists are thus generally dealing with historic bodies as a collective, holistic element and they can be related to as common ancestors, rather than family. Occasionally the anonymous ancestors are given new labels: for example,

Nordström (

2016) has discussed the creation of new biographies for Bäckaskog Woman or the Grauballe and Tollund Man bog bodies. Prehistoric archaeological identities are used as metaphors or icons and the people become known through the stories constructed around them, which can alter dependent upon the needs of society (ibid, pp. 227–29).

In historic cemeteries there can be exceptions where nameplates, jewelry, and private burial vaults provide names which can be compared with registers. In a similar manner to the prehistoric individuals, these examples are used as proxies or representatives for the rest of the burial population or the parish. They can be used to create stories of an average life in the community which is successful in creating a relatable human dimension to the skeletons (for example,

Emery and Wooldridge 2011). Recently a number of London cemetery excavations, such as the Bethlam burial ground (

Hartle 2017), have utilized volunteers to research and digitize burial records. This has the dual role of enhancing community engagement and providing relevant background research. This research allows sites where no excavated graves are identified to select historically documented people who are known to have lived in the community to perform the same representative role (

Brickley et al. 2006, pp. 229–36).

Yet images of the identified graves and skeletons are rarely explicitly named in these publications, instead the anonymous archaeological context numbering is used in captions perhaps to proffer a sense of professional and scientific distance. This approach was used in the excavations of Australian and British First World War soldiers in France (

Loe et al. 2014) where many individuals were identified. The intimacy of the events of their deaths and burial treatment were detailed but never linked to names, families, or descendants, many of whom contributed to the project by providing DNA for identification. While researching and digitizing burial registers or death records provides fascinating background, the connection between material body and contemporary documented information continues to be separated. There is clearly a difficult balance to be struck between a desire to sensitively engage communities with interpretation but not to explicitly identify individuals or families. A good reason can be that naming these people was simply unnecessary for the published research and it risked ‘voyeuristic intrusion’ (

Renshaw and Powers 2016, pp. 164–65). Anonymization can also be justified on the grounds of specific research aims being investigated (

Anthony 2016a, pp. 67–71). Yet by doing this the stories of individuals and families are also denied by being subsumed into general history.

There is another category of human bodies where names are used freely: the bodies of royalty or famous people. Why are these treated as a separate category where it is deemed respectful to publish details of intimate diseases and how the body was treated after death, when for others it is not? The discovery of the grave of King Richard III in Leicester, United Kingdom and the conservation of the mummified body of 17th century Archbishop Peder Winstrup in Lund, Sweden (

Buckley et al. 2013;

Karsten and Manhag 2017) are both examples of projects revealing intimate details of health and deaths of named individuals. Peder Winstrup’s body went on temporary display in 2015 and his mummified face and portrait were used as advertising material for the subsequent exhibition. The argument is not that these projects were wrong to identify or show images of the bodies; both projects handled public dissemination and social media sensitively. The argument is to question why it was acceptable for these bodies to be identified and made public, when others are not. Both people can be argued as public bodies during life, yet it does not follow that their bodies are of public interest once dead. If it is deemed socially acceptable to discuss these people in such intimate detail, then why not the identified bodies of the general public?

There are parallels here to the origins of genealogy which was used to establish lineage and descent for royalty and nobility, often for status, property, or dynastic purposes. The study of genealogy has since expanded, becoming more inclusive in its aims and sources; it continues to provide connections and lineage but has become democratized. Why should identified individuals and families of the general public also not be discussed, interpreted, and contribute to the knowledge of the past?

The ability to connect the anonymous dead with their names and perhaps part of their identities acknowledges their individuality but also provides potential pitfalls associated with using personal information and provoking emotional responses. After burial, individuals become anonymous groups of burials within cemeteries and churchyards which can be safely studied by archaeologists as a population. Simply excavating the bones may not be enough to re-attach identity as they have already passed into the status as ancestors, negating their status as individuals (

Renshaw 2010, p. 454). By anonymizing the dead the archaeologist positions themselves as above concerns about specific dead individuals or their descendants, and where specific ordinary individuals are used, the information is contained and corralled into carefully manipulated information.

In some ways this approach is shrouded in the term ‘respect’, although at the time of their death we do not, and may never know what respect meant to the individuals or their closest families. However there are societal expectations that become evident when some boundaries are crossed. Respect as a basis for dealing with bodies remains a nebulous term that means multiple things and may never be agreed upon. The complexities of respectful treatment of the dead are discussed by

Scarre (

2006, pp. 141–47) who suggests that the dead need not be considered off-limits but that the interests of the researchers, the dead, and their descendants may not always be contradictory and could be sensitively negotiated. By explicitly bringing names into research there is some element of increased subjectivity (

Rugg 2017, p. 213) but also the ability to craft narratives which acknowledge individuals within the general public, not just as collective ancestors.

3. Historical Archaeology and Genealogy: The Named Dead as Family?

Historical archaeology as a discipline combines the physical evidence of archaeological material with documentary sources. Theoretically and methodologically this prompts a search into how we can combine these varied sources which have differing source values, perspectives, and motivations. Following

Andrén (

1997, pp. 162–76) there are three basic modes of enquiry: positive and negative correspondence which examine the similarities or differences of documentary and material evidence, and association which searches for parallels either temporally or spatially with other societies. In truth most historical archaeologists use a combination of all three modes and in this merging and assimilation of the different textual and physical meetings is where we materialize the genealogy, finding the individual and families within the grave.

Genealogy has two theoretical ways of connecting to historical archaeology: the first through the everyday definition where connections between people are traced to show the family history. Inevitably genealogy is a selective process which has the potential to produce different histories by focusing on small-scale stories of specific people and lineages. It is an additional source of information to weave in with the archaeology and where there are grave plots of identified families, the genealogical connections become an obvious additional resource for interpretation. It is also a task that can never be completed: as all genealogists can attest, there are always more links to be researched. Secondly, genealogy has been used by archaeologists as a theoretical approach derived from

Foucault (

[1984] 1986) which picks up the metaphor but uses it to trace the descent of large-scale institutions and practices “where the narrative could change according to the specific starting point and the trajectory followed” (

Lucas 2005, p. 40). Different interpretations are created and there is more concern with the ephemeral, discontinuities, ruptures and reversals that are revealed (

Thomas 1996, p. 38). Here the genealogical connections and links have clear similarities to the way archaeological evidence is both formed and interpreted. Not only does this provide a structure to think about the archaeological evidence, it emphasizes the incompleteness, discontinuities, and ruptures within the multiple voices and narratives that form history.

Genealogy and archaeology have commonalities in both theory and practice and here we start to examine the contributions and relations that are supplied by genealogical information which go far beyond supplying an individual’s name. Genealogy provides positioning or context—a word beloved by archaeologists because it provides the ability to interpret and understand the materiality studied. The analogy is between finding an single artefact which may provide limited data on substance, technology, and aesthetics or belief systems but the information gained is multiplied if found within a context—a layer, a pit or a grave which can situate it within a society’s cultural institutions and practices. Current archaeological research emphasizes both the thingness of objects, that they have substance, are stable, durable, and also influence the world by themselves (

Olsen 2010) and the entanglement—the dependence of objects in networks (

Hodder 2012). The material objects, including the bodies, excavated in a cemetery contribute towards the mapped webs and exchanges of the genealogies; they provide what can often be regarded as the most uncomfortable aspect of the unearthed materiality of the cemetery. The genealogical approach is also closely related with the biographical approach of tracing the trajectories of specific people, objects, or places, providing interpretative insights that complement traditional forms of writing (

Mytum 2010, p. 242). Genealogy provides this context of family history—the networks which are physically manifested within a grave plot, how they might change over time and even be shared with others outside of the purchaser’s immediate family.

The materiality of genealogy is abundant; including personal documents, heirlooms, photographs, gravestones, old family houses, or workplaces. Combined with oral histories and official records these objects tend to direct what and how genealogical narratives are constructed. Ancestors that left only fragmentary evidence are less commonly pursued because their physical materiality and documentation no longer exists. Like Hodder’s entanglement, genealogical narratives are based upon active dependences between the seeker of information, materialities, and documentation and it is the link or relationship between them which is the important, even determinative factor in the creation of family histories. Here again there are parallels with research on death and bodies dominated by their physical presence and materiality (

Hallam and Hockey 2001). The entangled nature of human bodies which are physically and socially created and interpreted should be more connected to their materiality (

Sofaer 2006, pp. 86–88). If we also see humans and their bodies as part of this system, without losing their humanity, then we can see how genealogical approaches can provide a more complex interpretation. This research contributes towards taking the material step further by re-attaching names to graves through the creation of specific, complementary types of genealogical analysis of grave plots, families, and the archaeological evidence.

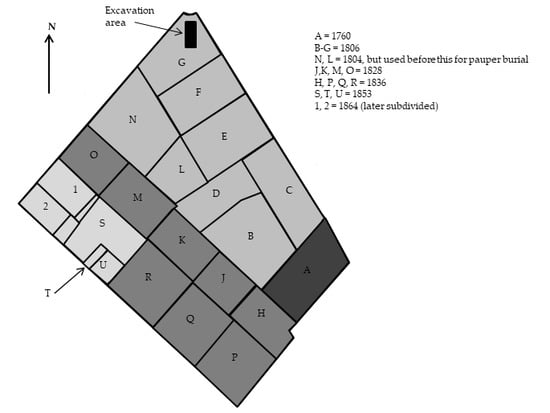

4. Excavating the Named Dead: Assistens Cemetery, Copenhagen

Whilst European urban churchyards, which were often closed by the mid-19th century, are commonly excavated, the type of burial provision that replaced them is not. The creation of a new Metro in Copenhagen resulted in the decision to place a station in one corner of Assistens cemetery and necessitated a project to remove the graves dating from the 1810s to the 1990s. Established in 1760, Assistens is an early example of a landscape, or garden cemetery (

Tarlow 2000;

Sommer 2003) designed and ordered according to fashionable contemporary garden principles and aesthetics. It is comparable with Père Lachaise in Paris, or Kensal Green and Highgate cemeteries in London where famous families and personalities of each city are buried alongside the general public. Initially the cemetery was shared between several city parishes and each division managed separately. The cemetery was extended in phases where each parish gained more space until the final boundaries were established in 1864 (

Figure 1). The overall design and landscaping features still in evidence today were added after 1806. Although partially still a working cemetery, the oldest section (Division A), is a protected Museum area and other divisions are now park land (

Helweg 2010, p. 131). In the latter part of the twentieth century coffin burial became less frequent, partly due to the preference for cremation but also linked to the decision to reduce burial in Assistens, focusing provision in other new city cemeteries.

Excavation from 2009 to 2011 resulted in the archaeological recording of the material culture of the cemetery including around 1000 coffin and urn graves, their funerary material culture and discovering aspects of the working life of the cemetery (

Anthony et al. 2016). Currently 82% of the in situ graves are identified but it is not simple to identify graves within a grave plot, even if the documentation of burials is well-preserved. There were very few nameplates or other direct evidence. In many plots there were two stacks, or columns of coffins and the order of burial may not be clear. Coffins are not always laid down one on top of the other in the correct chronological sequence, the earliest first and the last one at the top of the stack. Space is also at a premium and there was no eternal right of burial in Denmark. Plots could be abandoned and resold with earlier burials often disturbed, moved around, and truncated to make space for the new.

The excavation area was part of Division G belonging to the city parish of Trinitatis, now most famous as a tourist site for its round church tower. The parish was large and contained all classes of society although no paupers were buried in this division. Plot leases and burial rights were controlled by each parish and the nature of each lease depended on the type of plot purchased. The cheapest burials were single, or line burials which accorded burial rights, or grave peace (gravfred in Danish) for only 20 years for each individual, after which the grave can be removed and the space re-used. However plots could also be purchased for multiple (family) burials, the most expensive were in more visible areas along the cemetery walls and major pathways. Plots could be purchased and renewed, potentially for hundreds of years; above-ground gravestones, decoration, and iron railings were also permitted—for a price. Division G was largely full by the mid-19th century but continued in use for the next hundred years.

Division G underwent two major periods of spatial and administrative re-organization, the first from the 1830s when the original plot numbering system was replaced and line burials were phased out. The purchase of family plots was now the only option. This re-organization physically affected the landscape, a new design was enacted with some burial rows removed and turned into pathways. Uptake of the new plots increased in the mid-1840s. Crucially, the first system of plots was never surveyed, or if it was, then no maps survive today, the system had to be reconstructed using clues within burial records. Burial registers record details of each individual’s name, age, date, and cause of death, date of burial, home address, and plot number. Separate deed registers focus on recording the ownership of each the plot space and within the standardized template phrasing records the owner’s name, measurements of the plot and length of initial purchase. Each burial added to the plot would be recorded in both the individual register and the deed register.

The second major re-organization in the 1880s was associated with a unified administrative system which was now under municipal, rather than Parish control (

Helweg 2010, pp. 125–26). While most plots were physically unaltered by this change, they were given a third new numbering system. Fortunately both the second and third systems are mapped. Burials were recorded individually by the Parish and by the cemetery administration. Purchase of family plots was recorded in deed registers and should, theoretically, also record all of the activity within that space.

In the 1880s new registers and new systems for deeds of ownership were created which were largely based on earlier systems. However there was a distinct focus on the future, rather than recording the past. Rare is the clerk that deliberately links the past to the present. One example is on a deed from 1819 where the ownership is not renewed and the plot (P701

1) reverts to the church again. The clerk has cross-indexed to the new deed volume and page. However the majority of deeds are simply crossed through, with no indication of what happened to the space next. Only if burials were considered legally active then they would be copied over into the new system. Earlier burials were erratically recorded and there is little systematic logic for which burials would be kept in the records. Most commonly burials of young children were omitted, but this is not a rule.

To summarize, there are three systems of plot numbering, the first with an unknown layout and multiple, sometimes contradictory burial registers with only occasional clues to the earliest plot system. Most of the data used here is derived from two sources: databases compiled from the municipal registers held in Bispebjerg Cemetery Office and the Parish-based burial and deed registers in the Copenhagen City Archive

2. The multitude of administrative procedures left ample space for creative spelling, omission of entries, and poor transcription. Therefore genealogical sources were vital for accurately reconstructing and understanding the burial population: to reach a richer and more complex understanding of the cemetery, names and family histories matter.

5. Investigating Archaeology through ‘Everyday’ Genealogy

Archaeological research tends to deal in fragments; there is rarely a full record of what happened, material can be removed, lost, or simply decay. Assistens was an opportunity to explore what happened in detail in this three-dimensional space of events, actions, and decisions that were not necessarily entered into the documentary record. It also provides an opportunity to combine different types of source and ask new questions about the past that come from an archaeological perspective. In combination with genealogical sources such as family histories, publically accessible internet genealogy sources and compilations of notable Danes (some of which includes photographs of people excavated) and oral histories, the families and their relationships provide detailed individual information that can challenge available sources. It may also be possible to in future investigate familial DNA in combination with other commonly used genealogy registrations.

Genealogical sources have enabled the confirmation of names and correct ages at death, filling in given names where only a surname was used or where faded or elaborated 19th century Gothic Danish handwriting is unclear. The benefits are clear in confirming which specific person is referred to where there are similar names and clarifying familial relations or marital status. For example, some registers do not record age at death; a burial described as ‘the son of Workman Nielsen’ is likely to be a child but potentially could be any age ranging from stillborn infant to an adult. Where there are multiple graves in a burial plot that are unidentified, finding the documented sex and age of who should be in that space is vital. This level of verification of information from multiple sources is the most standard but fundamental advantage of utilizing genealogical information to benefit archaeological research. Genealogical sources therefore have aided in providing a separate source to confirm identities and understand who was placed in the family plot.

One example is the Meyer plot (P549) within Assistens containing the graves of a female and male adult. The skeletons were relatively well-preserved but the coffins were extremely fragmented with no elaboration or design observed. This suggested an early date of burial and it appeared as if it would be a simple identification. According to the original deed, the plot was purchased in 1815 for 100 years, however only one burial, the female owner of the plot in 1835, was in the register

3. Purchase of the plot was early in the use of the cemetery and was one of the most expensive locations; it was extremely unlikely that anybody else had been buried prior to the purchase. The deed also recorded the movement of a gravestone onto the plot but not a coffin, it also gave details of the widow who bought the plot and who was referenced by her husband’s name and occupation. The gravestone commemorates the husband who died in 1814 (

Helweg and Nielsen 2010, p. 570), one year before the plot was bought. Burial registers searched using his date of death revealed that he was originally buried within another section of Assistens

4. Genealogical records indicated that the couple had no children and confirmed the likelihood that the unnamed male burial was the husband. The evidence suggests that the gravestone and coffin were moved together into the plot, and as the age, sex, and preservation of the individual agreed with the documentary information, the couple were able to be identified. The combination of sources was the key to identification; it was as much about the elimination of other possibilities as confirmation of the correct person.

Comparisons of osteological, archaeological, and documentary information can also help to resolve questions in methodology, particularly the different methods of assessment undertaken within a time and financially constrained archaeological project. Osteological methods for determining biological sex and age at death are complex, age at death for juveniles is easier to determine than older adults. The considerable numbers of older adults with documented age at death in Assistens can be used in future studies to improve the accuracy of current methods. Biological sex of juveniles is not possible until the skeleton has developed sexually dimorphic traits after puberty, but DNA analysis can be used (for example,

Tierney and Bird 2015) and there is also the potential to explore this further within kin groups.

Burial customs can also be explored, for example many burial places appear to be missing significant quantities of juvenile burials, suggestions have centered on the fragility of juvenile bones compared to adults, different burial treatment or even separate burial areas (

Lewis and Gowland 2007;

Buckberry 2000) but it could also be connected to incorrect ideas regarding demography and the infant mortality in past societies. Where there is a cemetery of clearly identified burials with burial registers, some of these assumptions can be tested (

Murphy and Chamberlain 2017). Grave diggers practices have also been highlighted in the unofficial practice of burying small children in other people’s plots or around trees (

Anthony 2015). This scandal was reported in local newspapers

5 and reassurances were made that it would not re-occur but there are several examples found archaeologically which are dated after 1906 that show the practice continued. In these plots genealogical research was able to suggest that there were no other likely children within the family that may have simply been overlooked or missed out within the official burial registers.

Genealogical sources have also provided additional information. For example, only three female occupations were recorded on gravestones or burial registers (

Anthony 2016a, p. 160). The question of why it was not recorded in cemetery administrative records or gravestones in comparison to other official records is unclear. Male professions were commonly placed on gravestones and routinely placed on burial registers. Yet women did work both inside and outside of the household and the information from the census, family genealogy and oral histories have shown the great range and diversity within the female working world. This helps to restore women’s economic and professional contribution towards society.

When the family history has been created, the absence of certain members of the family in the burial plot is striking. In Assistens, married women are found less often in the same plot with their husband’s family. Instead many women were buried in their parents plot. The inclusion of a female with a different family name but the title of a wife (Fru) often denotes a married daughter; one example is of Fru Elisabeth Tolderlund who was buried in her Westrup family plot (P21) aged 27 years old in 1899

6 of anemia related to miscarriage or premature birth and was buried with her infant. These may have been inherited problems as her mother also died in similar circumstances, aged 28 years in 1875

7. Unmarried siblings, particularly in large families, were also buried with parents or grandparents, with married siblings choosing to buy a new plot.

A final example is used to show the combination of sources to gain most information. In contrast to cemeteries in the UK, there were very few nameplates and coffin fittings in Assistens which hampered direct material identification of graves. The most elaborate example found was a coffin in the Keutsch family plot (P668) containing an oil lamp, a cherub leaning on a book with a Bible reference and a small rectangular nameplate bearing name, and dates and location of birth and death. It is a rare example of combined documentary and material evidence stating that the man, Harald Keutsch died in 1872 when 20 years old. This was important information because the osteological determination of sex suggested potentially female morphological traits.

The plot was bought in 1846 by Henrik Matthias Keutsch, originally for 50 years but was later extended until 1909. The first burials were his and his wife’s two infant daughters in April and then September 1846

8. However a long gap occurred with no burials until Harald’s in 1872. The nameplate showed that he was born in the island of St Croix, one of the small colonies in the Virgin Islands, which was held by the Danes from 1733 to 1917 (

Rostgaard and Schou 2010). His nameplate supplied the necessary clue to understanding the long gap between burials. The family moved to St Croix and are registered as living at Christiansted

9 but sometime after the death of the husband in St Croix, his widow returned to Copenhagen. Harald died in Hamburg and his body had to be transported back to the family plot, and this too may help to explain the uniqueness of his coffin. The seven days between dying in Hamburg on 3rd November and burial reflect the journey time. The decorations and cloth covering could express typical German funerary customs and the need for identification during transport across official borders. Reconstructing the genealogy also confirmed the absence of the original owner of the plot. The everyday genealogy added to the plot’s narrative; it explained the large gap in burials and why the owner was not buried there and adds a link to Danish colonial history.

6. Alternative Genealogies—Families, Burial Plots, and Archaeology

Genealogy is not simply concerned with the use of another source of data but also encourages a new way of thinking about the narratives of the past. The advantage of using a genealogical approach is in identifying the multiplicities of possible narratives. Following the thread or lineages of different sources has produced three alternative genealogies that describe the entanglement of materialities and relationships that are involved in interpreting graves: familial, burial plot, and archaeological. One family, the Mønster’s, is used to exemplify the alternative genealogical approaches. The aim is to depict these differing genealogies within two grave plots to demonstrate the correspondence and variability between documentary and physical sources, to depict the use of the cemetery as an integrated landscape rather than individual grave plots and to illustrate the flexibility of burial space below the ground.

The first, and most commonly known genealogy discussed is the traditional family tree illustration of generations branching out from one person which represents the familial genealogy: the genetic and marital connections creating the family history. The Mønster family owned two plots; one plot (P621) was purchased in 1842 and then a son purchased another (P683) 15 m to the south in 1848

10. The family was large (

Figure 2) and three generations were involved with the biography of these plots. The combination of the Mønster familial genealogy also shows the family members who were not buried within these plots, some died before purchase of the plots while others must have acquired their own grave plots. The familial genealogy shows the chronological order of death but not necessarily which plot they may have been buried within.

The family relationship can be compared with the burial plot genealogy. Compiling the different burial registers and plot deeds created a list of burials from first (lowest) up to the last, making a chronological list showing the links between graves from several different families who had leased the plot (

Figure 3). It extends beyond the family history of the Mønster’s because it connects several other family ownerships together within the same space. The focus in constructing this burial plot genealogy is the location and tracking of positive events—the addition of burials, and it only rarely records negative events—the removal of burials. It is not confined to one specific family’s usage but to the place. It illustrates the official record and is also rather theoretical. The practice of grave peace, which is common in continental Europe, where after a defined period of time the grave could be removed and the burial plot reused, results in the potential for clearance of older graves. The burial plot genealogy indicates that there were probably two burials in each plot before the Mønster’s purchases. There were seven Mønster burials in P683 and six burials in P621. However two child burials were transferred between the plots, five and two years after their original burial. The lease of P683 continues until 1970 when new burials were being discouraged by the cemetery. The lease of P621 finishes in 1907, the plot is divided two years later and each plot is purchased by other unrelated families, adding another seven burials. In total, the burial plot genealogy of P621 contains thirteen known and possibly two other earlier burials and P683 nine known burials.

In contrast to the broader narratives of the family and burial plot genealogies, the archaeological genealogy supplies evidence of the physical remains that were still present at excavation. The archaeological genealogy illustrates the evidence of in situ burials (a stratigraphic matrix) showing the chronological order of evidence as it was found. This produces a different narrative of how the space was used, how graves relate to each other and what is preserved. Large grave plots have two columns of grave cuts that the gravediggers use repeatedly, sometimes over hundreds of years, placing the coffins in a stack with soil between them. As space within these stacks is limited, older coffins are removed, truncated (cut in half with bones either removed or scattered within the grave cut as charnel deposits), or pushed aside. The archaeological record depicts what is still present, in whatever form: intact coffins, truncated coffins or fragments of wood, bone, clothing, and grave goods. It is not necessarily correct that the uppermost coffin is the latest burial and the coffins are chronologically earlier as you excavate downwards; coffins are moved about, some are left in situ and many of the coffins closest to the ground surface in Assistens are in fact the earliest dated graves. New relations are materialized within the grave, both physically and contextually. There may be additional, unrecorded unofficial graves put in by gravediggers or there can be remains of burials still present from previous owners.

This archaeological genealogy is simplified to represent the combined evidence of each in situ grave (skeleton, coffin, grave goods, cut, and soil deposits) as a single event

11 or group (

Figure 4). Plot 683 had two clearly defined stacks which contained six graves, three female adults; two male adults and one infant, approximately one year old were excavated. A single deposit of human bones was recorded as charnel. Plot 621 was more complex with many overlapping graves; eleven in total, with five adult females and four adult males, two graves were present only as truncated and empty coffins. There were also two charnel deposits of human bones.

There was variable preservation with many of the most recent coffins poorly preserved due to cheaper, thinner wood and with little or no grave goods present. Earlier burials had elaborated black-painted coffins with plaster decorations of swagged drapery and baskets with flowers but were also heavily truncated, leaving only the head to the torso of the skeleton present. There were similarities of decoration between the plots with the earlier black-painted coffins and more frequent grave goods such as one burial with an inscribed gold ring. In P683 some of the later coffins were destroyed by gravediggers to make space for the last. These actions took place slightly after the official grave peace of 20 years had elapsed and by comparing to other graves of this period, there is significant chance that there were substantial human remains present at the time of removal.

Evidence of eleven coffins were excavated in P621 (

Table 1), two had no skeletons in situ, just the remnants of the coffin. Of the seven individuals documented from families buried after the Mønsters, six were excavated and identified. There was no evidence for the burial of a two-year old child. Of the six Mønster’s buried, two were children transferred out to P683 and only one adult male could be identified from the remaining three coffins excavated from this ownership phase. Identification is not always clear: two graves, one of an adult female and one without any trace of the skeleton, represent the burials of three adult women; they are impossible to separate and identify as specific individuals. There were also two adult graves which are stratigraphically the earliest, indicating the presence of remains of a family prior to the Mønster’s. Two charnel deposits derive from some of the truncated coffins.

There were fewer disturbances in P683, six graves were excavated but one was a coffin of an infant placed directly on the lid of the last documented coffin. There is no documentation for the infant and it remains unidentified. All of the five Mønster adults were excavated and identified but there was no evidence for the transferred child coffins from P621.

The amount of disturbance required to fit the graves within the small spaces of both plots is exemplified through the presence of three charnel deposits representing several adults. However in neither plot was there evidence for the two child burials that were transferred between plots, it is likely that their fragile skeletons were further disturbed by gravediggers. A further point can be made regarding P621, where multiple families had purchased the plot space for their loved ones. According to cemetery regulations

12 with each new purchase the previous graves should have been removed and disposed of within communal pits, yet there is material evidence present of all the families that leased the space. If the last family were to stand by the graveside and remember their loved ones, they may not know that the space was still physically shared with (some) of the previous occupants. The extent of removal of very recent graves may also be emotionally charged, in P621A the 1931 burial of a two year old boy was entirely removed for the burial of his grandmother in 1952, simply to make space, or possibly because the plot had formally been repurchased rather than renewed.

The archaeological genealogy represents a contrast to the linear record of the burial plot, it shows the positive and negative actions needed to maintain the plot as a viable burial space and includes all the archaeology regardless of formal ownership periods by different families. It also creates different physical links between members of the family with adjacent, overlying coffins and shows the uncertainty of identification where there is not one, but two stacks for burial, imprecise age at death for adults and the presence of undocumented graves.

The Mønster family plots reflect the pattern in Assistens of plots used for parents, children, or grandchildren who died young or unmarried adult children. That the son decided to purchase a plot close to his father’s indicates the social significance of this Division in the cemetery and perhaps the desire to be physically close to the older generation and siblings. The cemetery landscape was used to link the burials. The physical link was strengthened through the movement of two children from their grandfather’s to their father’s new plot, when their mother died. This is not simply symbolic but clear evidence that physical proximity was desired even in death and that despite being buried for several years, their bodies were still active in the representation and ideal of this family. There are also similarities of coffin styles between the two plots, with earlier burials painted black and individually decorated, and in the 20th century, families preferred the factory produced white-painted coffins with standardized wooden decorations and handles.

Other families chose to purchase plots close or adjacent to each other, and creating genealogies for other plots revealed significant sharing of space, similar to practices documented by

Strange (

2003) in the UK. The Pandrup family plot (P731) was purchased in 1820, and in 1872 the plot to the west was purchased by a daughter and son-in-law

13. The grave of a grandchild was placed across the boundaries of the two plots, perhaps physically reflecting her descent from both, despite the two plots never formally being combined. It was only the familial genealogy that revealed this connection and explained the unusual location of this grave. Above-ground materiality can also cross boundaries, the Sass family plot (P611) was left in situ during part of the excavation and gravestones were still present. One of the gravestones appeared to originally derive from the adjacent plot, the Petersen’s (P612) and the two plots were bought only one year apart in the 1840s

14. Checking through family records revealed the link, first by connecting the related professions of shipbuilders and ship’s captains, then through marriage records, meaning that siblings, nephews and cousins were buried side-by-side

15 and later their gravestones were grouped together.

There was clearly a desire to mark out familial links within the landscape. A grave plot should in theory separate out the buried group from others, but in reality these formal boundaries were more flexible, sometimes being actively chosen by the families. The underground is conceived as a flexible space, the boundaries of plots and graves are porous and the archaeological genealogies results in connections that bind together different families which are not obvious in the documents or gravestones. Investigating and connecting plots demonstrates how the cemetery is envisioned as a holistic landscape by mourners and which spatial connections or social affiliations were considered important enough to be materialized (

Buckham 2003).

Another significant connection comes from the recording of oral histories by the Copenhagen City Archive. One particular example from Ninni Wolf

16 describes visiting her parents in the Krarup family plot (P682) and although the plot lease ended in 1980 and gravestones were removed, she knew the location from the position of surrounding trees. The regulated cemetery system for organizing burial space continues but it did not stop Wolf from returning to the site despite not having a formal right to the plot. Wolf knew that her great grandfather, a manufacturer, was also buried there but within the plot were nine more relatives she may have been unaware of and also another plot nearby, of the Bonnesen family who were related by marriage (P723). All of these details including descriptions of her mother’s death bring a more human quality to the investigation of their excavated bodily remains and burial choices.

7. Engaging with Descendants

There is a wealth of documentary information about 19th and 20th century people, much of it administrative and rather impersonal but there can also be some surprising moments of connection. Archaeologists excavate, analyze, and write about skeletons and graves, with a focus on making broad-scale interpretations on their community, living conditions, diseases, and perhaps cause of death. But it is another perspective to know their name, their family relationships, how many children they had and which of them died in infancy. Still further and deeper is the connection made in stumbling across a photograph on the internet or archived reminiscences of a family that were excavated. Here is evidence of what they looked like, family resemblance, and what they chose to wear for formal photographs. A photograph contains a closeness and contact with the human body at the time it was taken and this shared space evokes an intimacy with the departed (

Hallam and Hockey 2001, p. 143) in a similar manner to excavating a body. The contextual entanglement deepens through meeting the ancestors face to face which promotes further intimacy beyond the handling of their skeletal remains.

Further boundaries are crossed and potential created when there is direct contact with descendants who are often interested in genealogy. During the research process there have been only limited enquiries from descendants of families buried in Assistens; their questions concerned how excavation had affected their ancestor’s plots and focused on the above-ground features such as what the grave plot looked like and if there were any surviving gravestones or photographs. The below-ground evidence was rarely the subject of initial questions, most assuming that burials over c. 100 years would be perhaps nothing more than a few fragments of bones. It took some dialogue and sharing of information before more specific questions were asked, particularly in relation to genealogy evidence known by the families. For example, descendants from one family had demonstrated that an ancestor had regularly altered her age for administrative documents so she would appear significantly younger. Did her skeleton show any sign of a youthful appearance? Other questions were about objects in the grave but in general few were about the skeleton itself.

Discussion with descendants

17 revealed that they were in general relaxed about the removal of older generations, especially if the grave plots themselves were no longer legally owned. One descendant responded that they were pleased and proud that their ancestor’s information would contribute towards scientific research. More recent burials provoke more concern, particularly if there were direct living descendants. Interestingly the removal of the graves was considered more acceptable if there was nothing left above-ground for an ordinary visitor to see, it was the visibility and connection between above and below the ground that meant that a person’s grave was still relevant. Overall these descendants were already actively seeking information about their ancestors, that they had known about the excavation and that grave plots are not purchased for eternity in Copenhagen may imply that they would be more open to this new information. Yet their attitudes also mirror the general reaction received from audiences in public lectures by the author. There have been, as yet, no strongly negative reactions to the project or related research. Instead ethical responsibilities have been frequently raised with questions revealing a general lack of knowledge concerning grave peace in continental European cemeteries. This has prompted people to look again at their own family graves, not for the fear of archaeologists digging their dead but from the idea that this routine practice of clearing grave plots may be occurring to people that they knew well in life.

Engagement with descendants has so far been limited and these observations must be treated with caution as their attitudes may be somewhat biased by their active interest in genealogy and prior knowledge of the practice of grave peace. Reactions received whilst engaged in community outreach however do highlight the general public’s gap in knowledge about the realities of cemetery management that need to be addressed further. However there has not yet been the challenge of meeting descendants with what may be upsetting or provoking information. More than once, concerns were raised over the discovery of potentially upsetting information such as evidence for murder, suicide, or diseases associated with perceived moral failings such as syphilis or alcoholism. These stories may be known by the descendants but would perhaps be treated differently if the information were disseminated widely. Of the graves excavated in Assistens, two were found with osteological evidence of violent deaths and one is used as an example. The remains of a young female adult in an elaborate zinc coffin were excavated with gunshot injuries and a bullet. Her hair was arranged to cover her wounds. Burial registers record her as being found dead in a hotel in Berlin

18. Contemporary Danish newspapers reported the story of her being murdered or possibly involved in a suicide pact with her lover, just months after her marriage to an Englishman

19. Registered as ‘found dead’ can be a useful euphemism, it can also reflect the uncertain legal situation in which she was found—was it murder, or suicide? Is this a scandal which would intrigue or upset descendants? Is the disturbance of her body different in comparison to others because of the tragic details of her death, or the description of her injuries? Ultimately presenting the evidence but dealing empathetically with these cases is the only real solution. To ignore stories or evidence in individual histories because they are considered difficult is to be dishonest about the past (

Anthony 2016b). It is often secretiveness and attempting to control information from cemetery excavations by archaeologists that is a cause of tension with interested communities (

Sayer 2010, p. 138).

8. Conclusions

This article sought to discuss the use of genealogical information and theoretical approaches within the existing debates surrounding the use of named individuals and personal data in historical archaeology. It crosses divides which archaeologists usually do not encounter, in using the names of the general public rather than well-known people and moving away from the discussion of anonymous dead ancestors. The burials of Assistens are instead striking in their normality and familiarity. It transgresses archaeological borders by excavating recent graves and in Denmark where the discipline of historical archaeology is a relatively new phenomenon (

Høst-Madsen and Harnow 2012) also beyond clear disciplinary boundaries. Cemeteries which contain family plots for multiple burials are arenas for the material expression of lineage, for display, and strengthening of units, whether genetic or other social groupings. Family histories and burial registers have been used to make a correspondence, or contrast with the materiality excavated below the ground surface. Through genealogical sources the research goes further in the recreation of family links and dependencies, examining the incomplete family histories of people who may have died within living memory.

One conclusion is that names and families of the general public do matter and, where we have them, it is vital to include them when interpreting and discussing past societies. However it is the responsibility of the researcher to consider other stakeholders which in this case study is the direct descendants of those excavated. Research in Assistens has led to examining one particular ‘slice’ or section of the genealogies of hundreds of families who are all buried in this specific section of the cemetery, generating a broad knowledge of four or five generations and how they were displayed and presented in death and what happened to their physical remains and remembered afterlives. Most probably did not know each other but there are some families that can be connected through the landscape which sheds light on cemetery usage.

Theoretical approaches to genealogy have inspired the methodology used where the disparate sources of evidence provided alternative narratives to specific places in the cemetery landscape. Focusing on just one family’s use of two grave plots, the different narratives formed by family’s descendants, cemetery and municipal authorities, gravediggers, and archaeologists were compared. There were shared correspondences where stories connected but also where the material genealogy was lacking in for example, missing coffins. The archaeological genealogies provided an answer for some of these gaps in the documentary narratives. Ultimately the three genealogies illustrated are complementary, highlighting different materialities and sources. Each also represents the gaps and inconsistencies within the evidence for an historic and well-documented cemetery site that is often imagined to be completely known and understood. This method may inspire others to explore the possibilities of working with such material.

Originally researching the genealogy was started in order to clarify and establish the numbers of how many people had been buried. This was a methodological challenge in combining both documentary and archaeological sources. What are the documents missing and where are the physical traces/presence and absences? Who was there? When were they buried and for how long were their remains present until disturbed, removed, or simply decayed? The work broadened into generating small relationship networks and engaging with family histories and very personal narratives which has allowed a more nuanced version of the cemetery to be offered. It has also led to direct contact with descendants which opened up the possibility of engaging with others. All of these genealogies were materialized in registers, deeds, gravestones, and in living descendants and their heirlooms, and there are more stories to tell. There are the stories of people who died with no direct descendants, those who died in infancy, siblings who never married or first spouses who died leaving no children. It is those who had children and continued the line of descent that tends to be focused upon, rather than the culs de sac of family histories.

Working with archaeological genealogies provides some of these stories but also adds more to the understanding of the connected family. In a study of people who worked with the dead,

Åkesson (

1996, p. 167) relates the responsibility felt by a pathologist to take charge and investigate all that they could for the benefit of the living and the dead. In this manner, when the opportunity arises, archaeologists should accept the responsibility to invite and create alternative narratives of named individuals, families and their burial space.