I am the daughter of an

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder (mixed raced Black German post-war child), the so-called “Colored occupation child.” There were “approximately 95,000 born in Germany shortly after WWII” (

Black German Cultural Society n.d., para. 2). Part of the baby boom between White German women and African American G.I.’s during and after World War II (WWII), my mother and her twin represent “an estimated three to four thousand children born between 1946 and 1953” (

Sollors 2014, p. 222) or up to 5000 (

Black German Cultural Society n.d., para. 2) children born during this period who were either raised in Germany, adopted by German families, or adopted outside of Germany (e.g., Denmark, the United States).

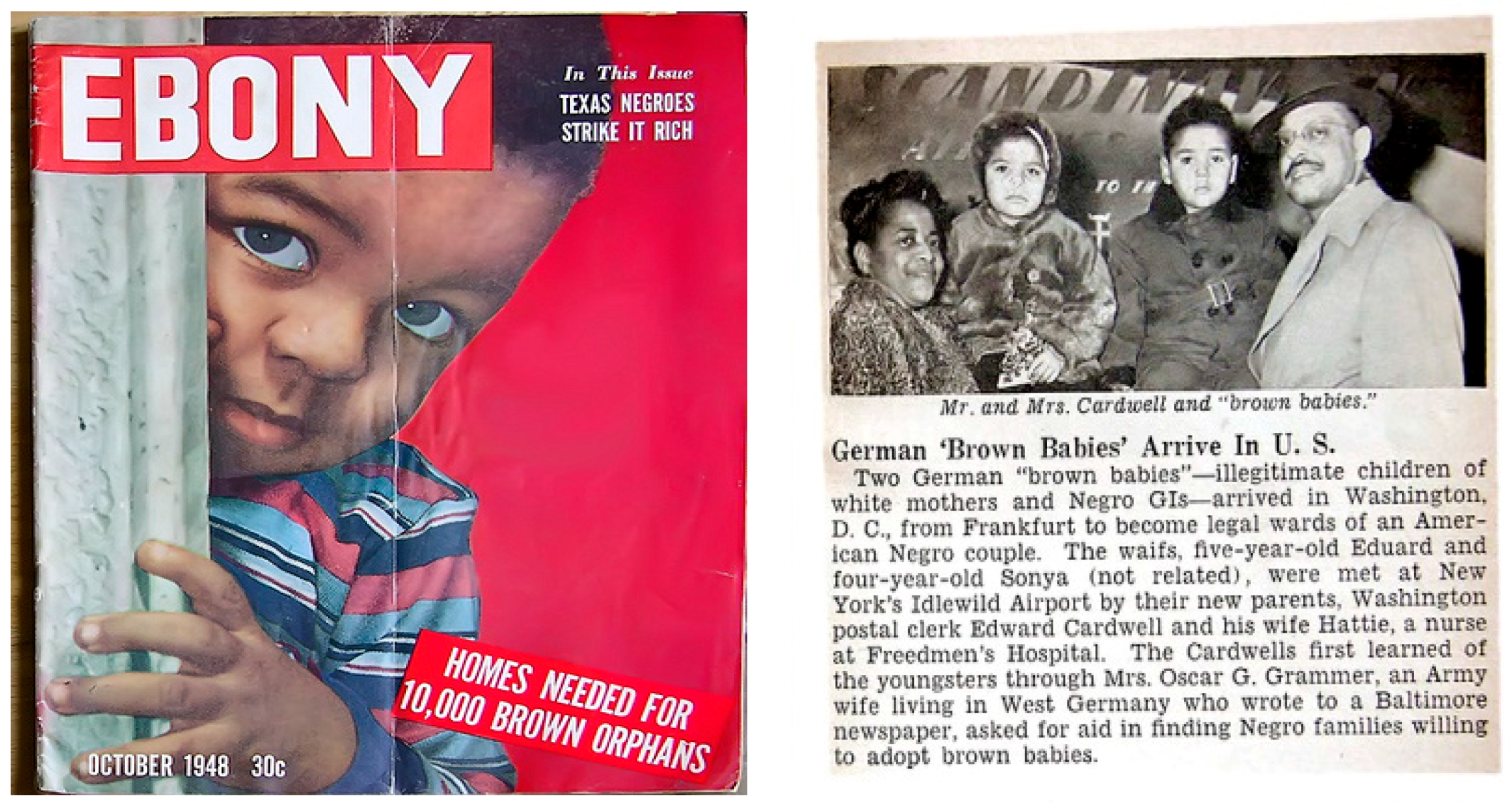

1 In the United States Black German children were covered in media such as

Ebony magazine where they made the cover of the October 1948 issue, “Homes needed for 10,000 Brown Orphans” or

Jet magazine which featured a number of Black German children available for adoption in 1951 (see

Figure 1).

The goal for this mediated coverage was to have Black German children brought to the U.S. and adopted by African American families. My mother and her twin were eventually brought to the U.S. and later put up for adoption by their biological mother and adopted into an African American household. The twins, whose visible phenotype is White, were wrapped up in the diasporic exodus that purged

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder out of Germany and into seemingly more diverse locales in a desire to keep Germany White.

2It is the goal of this article to retrace the histories of three generations of German women (my

oma, my mother, and myself) as it concerns memory, race, and rejection and the actions of my

oma (henceforth referred to as Anna) when she signed away her parental rights of the twins in 1958 and allowed them to be adopted at almost 12 years old in 1960. The twins had no contact with their biological mother since the adoption. However, due to my curiosity and interest in my German heritage, my mother and I began the search for Anna in 2010.

3 On 13 July 2012, 52 years later, Anna, mom, and I were reunited and began the process of redefining what family is and how family can be constructed and reconstructed over the decades. Memory and post-memory (experiences that challenge the official documented histories that often leave out marginalized and decentered perspectives) are analyzed through three generations of women of German descent.

4 Using memory and post-memory as my theoretical framing, coupled with autoethnography, family interviews, and narratives as my methodological tools, I weaved in my own family’s history to show that mixed race children are the dross that must be removed from women, the nation’s wombs, to make room for a future Aryan child. What happens when we view these Black German children of the post-war generation not only through the actions of the biological mother, but also through the experiences of the children affected? How do we better understand the experiences of these Black German children of the post-war generation through memory, race, and rejection?

Memory, race, and rejection are complicated in all societies, but particularly so in Germany where the illusion of an all-White society remains a prominent narrative in the historical and social constructions of the country in spite of the multicultural groups who have long existed within its borders (see (

Partridge 2013)). Black Germans born during and after WWII, along with their memoried accounts of family and adoption, visually signify and orally challenge the official and historical narratives of WWII and its victims. This research adds to the fields and disciplines of Adoption Studies, African American Studies, Communication, German Studies, Genealogical Studies, History and Information Studies, as it concerns complicating the communicative and historical notions surrounding memory and post-memory. In this essay the experience of a “Black German” child post-WWII was used to explore these concepts.

1. Literature Review: The Black Diaspora in Germany

1.1. Colonial Germany, 1884–1918: Beginning Anti-Blackness in Germany

Imperial Germany (1884–1918) offers a valuable point of departure for an analysis of citizenship, race, and gender discourses that surrounds Black Germans, because it represents a first public discursive intervention into the construction of the raced citizen in Germany.

5 In the 1880s, Otto von Bismarck, the first chancellor of the German empire, established five German Colonies in Africa (Cameroon, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Togo) and expanded German colonialism in order to consolidate German political and economic strength relative to other imperial European powers; e.g., Britain, Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain (

Stoecker 1987). As some white German colonial settlers and indigenous African women in those aforementioned countries developed sexual relationships, the German colonial governments began to implement functional bans on interracial marriages throughout colonial Germany.

Campt (

2003) found that colonial officials, drawing on scientific discourses of race and fears of racial mixing as a threat to the “purity” of the White race, began to refuse the registration of interracial unions as early as 1890 and by 1912 interracial marriages were banned by colonial gubernatorial decree in Southwest Africa, German East Africa, and Somoa. Restrictions on marriage rights offered an important constraint on the notion of the German citizen, because it was through marriage that white German men extended the rights of the polis to their wives and children (see

Figure 2).

Campt (

2003) argued the colonial decrees against interracial marriages resulted in objections that culminated in the Reichstag debates of 1912 as, “one of the first important sites of public articulation for Germany’s response to its Black German population” (

Campt 2003, p. 327).

The 1912 Reischtag debates over interracial marriage in Germany drew on a gendered discourse that positioned White German women bodies as the protective barrier of the White German citizenry, and constructed Women of Color bodies as threatening to pollute German genetic stock with intrinsically deficient mixed raced children.

Campt (

2003) textual analysis of the Reichstag debates suggested that notions of German citizenship were intricately linked to a combination of “scientific and colonial discourses of racial purity” (much like the popularized Eugenics movement that had its beginnings in the Enlightenment era) and “gendered and sexualized discourses,” of the German body politic wherein the “German national body is a raced body made vulnerable through the female body as the conduit of racial pollution” (

Campt 2003, p. 330). Throughout the debates, Colonial officials constructed an image of the racially mixed children as a threat to the recognizable German family. Colonial Secretary Solf, speaking in favor of the ban on interracial marriage, warned of the risk of German men coming back from the colonies with ‘wooly-haired grandchildren’ who would bastardize the White German race and rupture the fundamental division between the White civilizing cultural force and the backwards Black colonial subject (

Fitzpatrick 2009). This racist attitude speaks to similar fears that cultural studies scholar, Martin Renes, noted with regard to Indigenous Australians, “the case … over the last two centuries … may speak back to European fears of displacement by the ethnic Other? (

Renes 2011, p. 30). Black women were constructed as exotic sexual seductresses, “vessels and conduits for transporting pollution and contamination into the German national body,” luring German male colonists into having mixed race children (

Campt 2003, p. 330). White German women’s bodies, in contradistinction, were positioned as sexually available protectors of the German stock and many white German women took up the position as barrier to the pollution of the (white) German empire (

Wildenthal 2001). White women’s roles, power, and value thus became positioned only as in relation to their uterus.

1.2. Post WWI Germany, 1918–1933: Consolidating Anti-Black sentiment in Germany

Approximately 30,000–40,000 Black soldiers, primarily African French colonial troops, were among the forces that occupied the Rhineland after WWI (

Opitz et al. 1992).

6 In distinction with colonial Germany, where the threat of Black pollution of the White German race was placed outside the German national body, the Rhineland occupation by African soldiers resulted in a threat from within the national body. In Germany, military figures, social and political leaders, intellectual figures, and the press responded swiftly, and with vitriol, against the Black occupying forces, and pushed a campaign, with near universal support, for a parliamentary petition that demanded that Allied occupied forces withdraw their Black troops from the Rhineland (

Opitz et al. 1992).

With the call to Whiteness to the rest of Europe and the United States, Germany attempted to assert its authority through its construction of the German citizenry as fundamentally anti-Black in the preservation of an assumed White-dominated world. Black soldiers were defined as hypersexual threats, riddled with sexually transmitted diseases and a polluted genetic stock, so their access to White women was a primary discursive concern for German men and their masculinity (see

Figure 3). Therefore Black men needed to be controlled.

As part of the deployment of the Rhineland Bastard, the children of Black soldiers were also depicted as the carriers of the infectious diseases of their fathers, in particular sexually transmitted diseases (

Campt 2003, pp. 336–37). Black German children became the bodies on which anti-black discourses played out throughout Germany (see

Figure 4). Subjected to forced sterilization as early as 1919, the Black German children of French Colonial soldiers and White German women were constructed as victims of their own circumstances and simultaneously unacceptable threats to the homogenous White German citizenry (

Opitz et al. 1992). While the Rhineland did not have a legal statute in support of forced sterilization and the children had the citizenship rights of their mothers, it is nearly impossible to accurately take account of the secret sterilizations of Black German children during this period of German history (

Opitz et al. 1992).

1.3. Third Reich Germany, 1933–1945: Institutionalizing Anti-Blackness in Germany

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, and the establishment of the Nuremberg Laws, much of the anti-Black discourse that was exacerbated after the First World War became enshrined in public law; e.g., interracial marriage.

Campt (

2005) argued Nazi Germany must be understood first from a racial perspective, where race is understood “as the organizing principle of social, political, and economic life in the Reich … (Nazi Germany was) founded on its ability to produce specific racialised categories of legitimate and illegitimate subjects” (

Campt 2005, p. 165).

Hitler laid out a notion of the state’s population into three distinct categories; citizen, subject of the state, and “alien” and argued that simply being born within the confines of the state were not sufficient to garner the rights of the polis (

Hitler 1939). Thus, citizenship, and the rights and protections that accompanied such a status, were not extended to the mothers of mixed race children or their offspring. Further, shortly after coming to power, the Nazi regime passed the Law for the Protection of Hereditary Health which called for forced sterilization of any person who is medically designated as posing a threat to the ‘health’ of the social body (

Haas 2008). While the Hereditary Health law did not use race explicitly, the sterilization policy and medical surveillance gaze was turned aggressively toward Black German bodies (

Haas 2008). Hitler targeted Black Germans as part of a robust sterilization program that resulted in hundreds of Black German children being sterilized, and hundreds of other Black German youth were moved into concentration camps (

Okuefuna 1997).

Firpo Carr (

2003), author of

Germany’s Black Holocaust, documented the experience of Black female holocaust survivors who described the scientific experimentation on their body and the racist epithets that they survived as part of the larger racist ideology that shaped Black German experiences in the Third Reich era in Germany. Scientific thought became a justification mechanism for the Nazi violence against Black bodies.

German women faced laws which circumscribed their choices of sexual partner to only those of pure Aryan heritage, and faced severe prohibitions and sanctions for engaging in sexual conduct with foreign men (

Fehrenbach 2009) including Black, Jewish, and Romani men. In 1930 the League of German Girls was formed which, like the Hitler Youth Group for boys, trained girls to become faithful to the Nazi Party. By 1936, young White German women were encouraged to have as many “pure” Aryan children as humanly possible. There was even the formation of the Hitler Maidens that all German women between the ages of 10–17 were required to sign up for and participate in (see

Figure 5). This group taught girls how to be good German citizens, and since they were women, this meant learning about the importance of motherhood.

The emphasis on the virtues of motherhood for German Aryan women was an indirect, coercive means of balancing out the ‘loss through degenerate offspring’ with desirable offspring. It is obvious that only those Aryan women who brought Aryan offspring into the world were glorified. Those who bore Afro-Germans, Sinti-Germans, or half-Jewish children were excluded from the cult of motherhood and were denounced as ‘whores’ in public and often by their closest relatives.

After the 1936 Nuremburg Rally (the Nazi Party rally), for example, 900 young German women left pregnant (

Rittenmeyer and Skundrick 2010). German women who had become pregnant through sexual relations with non-Aryan males were forced to terminate their pregnancies (

Opitz et al. 1992, p. 49). It is worth noting that women’s roles and power in Germany, particularly Western Germany, changed dramatically in 1972 when Western German women were allowed to retain their citizenship when marrying a non-German person and when anti-racist feminism was popularized in Germany by Audre Lorde in the 1980s (

Schultz 2012).

1.4. Frӓuleins, G.I.’s and their Children

German women who developed sexual relationships with Black men faced serious constraints over the rights over their womb and were discursively constructed as whores and prostitutes, sometimes forcibly sent to VD clinics, jail, or workhouses where they were held against their will (

Fehrenbach 2009;

Goedde 2003).

Fehrenbach (

2009) analysis of a 1950 survey on mixed race relationships showed that German women who had developed sexual relationships with Black GIs were seen as opportunistic and immoral. Germany, at this time, mirrored many of the same racist sentiments as the United States. For example, Germany continued to ban interracial marriages, the majority of the German press condoned and supported the violence visited upon Black GIs by White soldiers, and military police (MP) enabled a bond to be built between German and US men who “both agreed upon the necessity to ‘defend’ white womanhood and police white women” (

Fehernbach 2009, p. 34).Violence used to maintain the racial segregation throughout the US military was a lesson for the German democratic path forward on the meaning of democracy, and reasserted that democracy was still a notion meant for White Europeans.

German authorities subtly encouraged for German women who conceived children with Black soldiers to have abortions (

Fehrenbach 2009), yet abortion requests were disproportionately denied to women who had been raped by white GIs; e.g., Russian soldiers raped an estimated 2 million German women and approximately 1/10 of these women died after the rapes either from the rape itself or suicide (

Rittenmeyer and Skundrick 2010). While the subtle government coercion of abortion of Black German fetuses occurred at the local level, a non-married woman who was pregnant with an

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskind was a shame that she could never overcome. Phrases such as “

Negerhuren” (negro whore) were commonly heard and directed at these German mothers, therefore, “giving birth secretly, and letting German state welfare and adoption agencies, with their network of orphanages and foster parents, take care of the child, thus became a relatively frequent outcome, generating political worries about public costs” (

Sollors 2014, p. 222), but at least the stigma was no longer focused on the mother, but rather the living child.

In Germany these children were a scientific curiosity to anthropologists, like Walter Kirchner who in 1952, with the support of the Berlin Youth Welfare Office and State Health Office, studied the children to “assess whether different character traits and developmental patterns could be detected among Afro-Germans” (see (

Fenner 2011, pp. 93–94)). In 1955, Rudolf Sieg studied 100 three-to-six year olds in German orphanages comparing “the size and relation of limbs; assess hip width, arm length, shoulder span, eye color, length of fingers, skull length and width, ear size and determine[d] the tone of skin on a chart demarcating five shades from white to dark brown” (

Fenner 2011, p. 94). While Seig recognized the potential trauma of such observations, the

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder children had to endure the trauma of being treated like lab specimens since there was no law, no parent advocating for their equal treatment. “It is these children that became the main focus of assimilative government action; it is in their defencelessness (sic) that the breach of basic human rights is salient…” (

Renes 2011, p. 31). Lighter-hued children (those who could pass for White), were believed to have a greater chance of assimilating into White German society similar to what Renes noted about Indigenous Aboriginal children, “their part-white offspring was deemed intelligent enough to allowed for their biological ‘absorption’ into the mainstream through basic training, child fostering, adoption…” (

Renes 2011, p. 33). Like the children born of African American G. I.’s and White German woman, these soldiers also had no guarantee of equal treatment when fighting in WWII, despite the fact that in many places these men were greeted as liberators.

African American soldiers were engaged in the “Double V campaign” (victory abroad and victory at home) in fighting for a Europe free from The Third Reich and Hitler and a U.S. free from Jim Crow, but the reality was African American soldiers were fighting in a racially segregated army and most could be found in largely subservient positions (cooks, drivers, and service personnel) rather than as the famed Tuskegee Airmen and the 761st Tank Battalion. “German prisoners… had noticed that they were given privileges that their black (sic) guards did not enjoy, a fact Nazi propaganda exploited during the war” (

Fenner, 2011, p. 186 quoting Seig 1955). Even after former President Truman’s Executive order 9981 which integrated the U.S. military, “by 1952 only 7% of black (sic) American soldiers in Europe were serving in integrated units” (

Sollors 2014, p. 186). Given this context, marrying their pregnant girlfriends was not an option for these couples in Germany where interracial marriage was not favored by society and in the Jim Crow U.S. interracial marriage was illegal.

7 In fact, in the U.S. “interracial sex and marriage… were prohibited in thirty of the forty-eight sates, among them all Southern states where the majority of black (sic) Americans resided… when it came to issues like miscegenation, the army had a distinctly Southern feeling to it” (

Sollors pp. 189, 222). Therefore, having the “American dream” with 2.3 children and a house with a white picket fence was out of reach for these couples as there was a larger investment in the destruction of families rather than the governmental and social support of these couples who did not fit into the largely racially segregated society. Co-habitation in Germany as an interracial couple did not guarantee freedom either, despite some ease in juxtaposition to the United States:

My parents lived together in Germany where they wished; they traveled together where they wished; they ate together where they wish; and they had many German friends. It was when they returned to the United States that my mother and father were forbidden from traveling in the same cabin; it was when they returned to the United Sates that they couldn’t be stationed in most military bases; it was when they returned to the United States that we feared as a family when we traveled together during daylight.

By the time World War II ended, the U. S. racist and segregated treatment of African American soldiers is not lost on German society, and was often replicated in Germany. “Thus, when Germans expressed their opposition to interracial relationships during the 1950s, they often cited the American model of race segregation as informing their own views. Doing so allowed them to ‘normalize’ aspects of their discredited Nazi past” (

Höhn 2002, p. 107). Postwar debates over miscegenation did not suddenly come to an end after Hitler was no longer in power in Germany, rather the object of the discourse shifted from the relationships between Jewish men and white German women to the sexual relationships between foreign men of Color and white German women (

Fehrenbach 2009). Specifically, race discourse after the Second World War nearly always was linked to discussions of interracial sex and reproduction between German women and Black allied soldiers, but was carefully crafted to avoid speaking of Jewish and Slavic relationships with German women in explicitly racialized terms (

Fehrenbach 2009).

2. Theoretical and Methodological Frames

2.1. The Theoretical Frame of Memory

Memory is a powerful weapon in the desire to craft, shape, or reshape one’s life. “The most difficult part of beginning any story, any project, or any study but especially any history lies in the choices and decisions we make with regard to context” (

Campt 2008, p. 1). Memory and post-memory are not perfect nor are they representative of the “truth,” but memory is one of those contexts that has the ability to engage and center narrative hegemonic structures in favor of telling a story that wraps up in a nice neat package—one that has a beginning, middle, and end with no outliers and outlier effects that make the story less pristine than the packaging in which it was wrapped. The narrative I share here is a collection of stories and experiences that are subjective; there is no “official history” recounted here. I termed my narrative experiences “post-memory” because I specifically include experiences that are often disenfranchised and/or erased from the official, memoried, recounting. The “truths” I have here allow for Anna, my mother, and me to make meaning of rather significant and non-significant events in our lives; thus post-memory. Post-memory allows one to reshape, situate, and categorize the transformative and powerful images and experiences of one’s life in ways that create meaning-making and guide our lived and communicative processes. Post-memory allows us to situate ourselves in our lived experiences in ways that are reimagined for the narratives we tell ourselves and the narratives we tell others about ourselves. As the centered heroes of our stories, the primary thing that matters with how we are situated in and juxtaposed against others in our lives and in our meaning-making is that our memory and post-memory makes sense. Because our discursive and socially constructed world operates in ways in which language shapes thought, and thought shapes interaction and language, thereby “teaching us that reality is socially constructed and a “product of group and cultural life” (see social construction theory and

Littlejohn 1996, p. 34), what we know about ourselves through our relationship with others, as well as our perception of self, affects how we see, interact, and communicate with one another. It is in the process of meaning-making where memory and post-memory can be used as cognitive tools to challenge the hegemonic hierarchies often supported by language, thought, and interaction. “Particular representations of memory and history that have come to be institutionalized as narratives of ‘official history’ and national or collective identities not only leave out alternative forms of memory that have yet to be recorded... but also, by definition, render them invisible and unrecognizable by virtue of the fact that they are seen as unintelligible in relation to these official histories” (

Campt 2008, p. 14). Therefore, as a challenge to hegemonic hierarchies, one’s story and the sharing of the story creates space for experiences that are often left on the margins and/or erased and forgotten altogether.

Life is not lived in a vacuum, therefore, memory, post-memory, and recovery of memories have dispersive rhyzomatic possibilities and engagements that can bind diasporic experiences together (

Gilroy 1995). Once out of the confines of official histories and situated into diasporic frames, the use of alternative histories and memories make sense because we now have the tools to redefine or re-conceptualize “original history.” The use and recovery of memories are action-oriented in design because the articulation of the memories allows for an alternative way of knowing which has the potential to, if not dismantle the hegemonic hierarchy, at least allow space for the disenfranchised narrative to take root. As sociologist Maurice Halbwachs noted,

The past is not preserved but is reconstructed on the basis of the present…. The collective frameworks of memory are not constructed after the fact by the combination of individual recollections; nor are they empty forms where recollections coming from elsewhere would insert themselves. Collective frameworks are, to the contrary, precisely the instruments used by the collective memory to reconstruct an image of the past which is in accord in each epoch, with the predominant thoughts of the society…. One may say that the individual remembers by placing himself (sic) in the perspective of the group, but one may also affirm that the memory of the group realizes and manifests itself in individual memories.

If Halbwachs is correct, memory can be argued as an artifact, remembered, reproduced, and reinterpreted to function as an aspect of ones lived experiences, both collectively and individually. Thus, the root and the routes these narratives take to become part of our collective memories. The question then becomes what kind of present do we hope to make out of strategically remembering the past?

2.2. The Methodological Frame

The methodological frame chosen for this study involved autoethnographic reflections from Anna, a great aunt, my mother, and me (as the third generation). These narratives center our stories and our perceptions which are counter-hegemonic narratives to the official storied events of World War II. My narratives were collected in 2012–2015, and 2017. I was unsuccessful in meeting with Anna’s middle sister (my great aunt who still lives in Germany) in summer 2014 when I lived in Berlin because she refused to respond to my request for us to meet in person and get to know one another.

8 Most of my interviews were over the phone, but twice I visited my German family in person; once in 2012 and another time with an onsite visit to Hidden Villa Ranch in 2013, where my family once temporarily lived upon entry into the United States.

9 A visit to the Ming Quong orphanage in which the twins once resided in Los Gatos, California, was attempted, however, the orphanage no longer exists and has since been turned into a historical museum whose focus is on Chinese American girls.

10 Also analyzed were official documents obtained from the social worker involved in the adoption of the twins were incorporated as well to aid in the analysis of memory and post-memory. Participant observation and interview data allowed for a privileging and centering of memories and post-memories that might otherwise have remained unknown and undiscovered. The use of autoethnography, on the other hand, allows for the turning of a critical cultural lens on oneself. This methodology fosters a critical examination of one’s lived experiences, and allows her/his narratives and her/his experiences to be treated as primary data (

Jackson 1989;

van Maanen 1995), which is paramount in understanding, analyzing, and voicing the experiences of marginalized groups see (

Ashcraft and Pacanowsky 1996;

International Communication Association 1999;

Denzin 1997;

Geist and Gates 1996;

Murphy 1998).

I recognize that the generation and time period in which this study is conducted is limited, however, the small sample size does not negate the significance of this study, and using my family as an exemplar is apt given these three reasons: (1) the women who gave birth to the “Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder” children are aged into their early-to-mid 90’s or deceased. It is important to preserve their voices regardless of how small the sample size; (2) most of the women who birthed their “Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder” son or daughter refuse to talk about such a private experience. Thus, being shamed into silence gags and prevents the women from wanting to or choosing to speak about such private experiences; and (3) in the case of adoption, most adoptions during this time period were closed. Therefore, finding the birth mothers is extremely rare and involves time-consuming research and expense to which most people have little or no access. Using my family as an exemplar provides a rare glimpse into the often closed and silent world of “Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder,” particularly where one is able to include the voices of three generations of German women and their life experiences. Further, my mother and her twin were adopted at nearly 12 years old; twelve years to form genealogical bonds and memories with biological family that most children from this era who were adopted as babies and toddlers do not have, thus making this study unique. Given these conditions, the theoretical and methodological choices used in this study, memory and empirical analysis, are the best scholarly tools to examine memory and post-memory as it concerns memory, race, and rejection as it is related to this specific “Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder” experience.

3. Memory: The Imagined Past and the Sobering Reality

I am surprised that racism happens in this day and age. I am sheltered from all that as you know. To me, a Negro (sic) is no different than anyone else. You know, after the war (World War I) during the Occupation, we had a Negro (sic) down the street from us. I was afraid. My mother said, “a person is a person. Don’t be frightened by his skin color. He is probably just as afraid of you as you are of him.

(Anna, personal interview)

Black people in Germany were not uncommon, yet in WWI and WWII African and African Americans were more prominent in their roles as post-war soldiers; temporary sojourners rather than long term residents or natives. However, an article found in the

Teltower Kreisblatt newspaper in April 1882 reported that “Berlin had a ‘

Neger colony’ of sixty people both from the United States and Africa... Many of [the people] were not only fluent in German, but even spoke in a Berlin dialect; three men were married to ‘white girls’ and their children were said to be doing well at school” (

Aitken and Rosenhaft 2013, p. 1). Anna’s first encounter with a Black individual happened when she was a youth (as noted above) and her second happened with her romantic relationship with a mixed race African American WWII soldier. “He swept me off my feet, literally. He danced like an angel. He twirled me around. I never knew I could dance like that. He was very nice, we were friends. He was very light-skinned with slightly curly hair and very proud of his Native American heritage. Race never mattered to me. It was always the person, never the color” (Anna, personal interview).

11Race being irrelevant is quite a departure for the indoctrination that Anna would have received as a young woman, given that she was mandated by the Hitler regime to be part of the Hitler Maidens. Her description of the man she referred to as the “love of her life” and the “man who swept her off her feet,” would likely induce cognitive dissonance particularly since he was likely part African American, therefore, there is poignant absence surrounding his race as it concerned any Black heritage. It is safer, more acceptable for him to be anything but Black. It was safer for Anna for him to be anything but part-Black as well given the lack of societal acceptance of interracial coupling during and after World War II (see Literature Review). Both in Germany and later in the United States she saw the racism that Black people endured, and while she was in a city in Germany that had the most biracial children born during and after World War II, she knew there was a strong thread of racism and exclusion that ran through both countries. In Germany Anna said she was called a “Negerhuren” (Negro whore) and worse. Because of the trauma of racism she left her children to deal with racist German society on their own. Later in 1958, when she gave up her children to become wards of the state in California, she could barely acknowledge the race of her lover when establishing the narrative for why she was giving up; his race vacillated from “Negro” to Native American, to even White.

In my 2012 conversation with her, Anna never uttered the word Black or African American. When I asked Anna for a picture of him she said there are no images of him available because she destroyed them stating that “some images are just too painful.” Our conversation about her boyfriend’s race abruptly changed to issues of socioeconomic status and basic needs. Topics not related to race were safer and more acceptable. After WWII, “everyone had to work. As soon as you were old enough, you worked. We were all so hungry and so cold. I had two jobs” (Anna, personal interview). During this time of working, Anna met and eventually lived with a WWII American soldier who would give her things like “chocolate and stockings” and was “nicer than the German soldiers,” as well as provided an apartment for the two of them to live in (Anna, personal communication). This apartment with her boyfriend was crucial, particularly so because she previously lived in a two bedroom apartment that was crowded due to the post-war housing shortage where my great grandmother and my two great aunts (my grandmother’s sisters), and Anna all lived together.

The actions that Anna and her boyfriend took would have violated the anti-miscegenation laws in the U.S., as well as the racial purity notions in the Third Reich of Hitler. While there were no anti-miscegenation laws in Germany, after twelve years of Nazi rule, the stench of racial purity was palpable and cries of

rassenschande (racial shame) rang loudly against those engaged in interracial relationships. For example,

a military government opinion survey taken in Germany in April 1946 showed that about a third of the respondents still expressed openly racist attitudes toward Jews and only a slightly smaller number toward blacks…. As late as 1951, though more than half of German respondents to a once-classified survey said they would be willing to invite western Allied soldiers into their homes, the numbers dropped by about half when it came to Negro (sic) soldiers, with the majority declaring themselves unwilling to do so.

Regardless of the aforementioned percentages, the presence of African American soldiers in Germany opened up a world of possibilities for all African Americans, because the soldier presence there and the difference in treatment “allowed African Americans in the United States to imagine a space where the freedom and equality denied them in their own country became possible... and revealed the contradictions between America’s ideal and the reality of life for African Americans…. Post-war Germany emerged as an unexpected site for advancing the civil rights cause” (

Höhn and Klimke 2010, p. 62) particularly because soldiers after fighting for freedom and democracy in Europe returned to a U.S. firmly entrenched in racism, segregation and Jim Crow law.

While White Germans from that era, including Anna, acknowledge the kindness of African American G.I.’s, including their willingness to purchase scarce coveted items like chocolate and stockings, “

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder” “became a visible signifier of German national defeat” (

Fenner 2011, p. 27). Child-rearing because of oppressive cultural norms fell to the labor of women. “The West German government became embroiled in disagreements with the U.S. military about who should assume financial responsibility for children fathered by American soldiers, given that most enlisted men had returned to civilian life in the United States, leaving German mothers to raise the children alone” (

Fenner 2011, p. 28). Anna found herself in the similar position of being a single parent: “I told him I was pregnant. He told me he had a wife back in the U.S. and broke up with me, choosing the other woman.” He left. Anna never saw her boyfriend and the biological father of the twins again.

12Because of her pregnancy and her boyfriend leaving, Anna could not afford the rent for her apartment. She was forced to move back into the overcrowded apartment where her mother and her sisters lived.

13 Attempting to hide the pregnancy from her family, she sought advice from the local Catholic priest in their city. “The priest told me he could not and would not help me and then kicked me out of the religion and the church. He told me I was no longer part of the Catholic Church and to leave. After that, I was in denial about the whole pregnancy” (Anna, personal interview). As a twenty-six year old single woman working two jobs in the post-Hitler era, Anna chose silence as the option to deal with her unplanned pregnancy. Following the allied occupation of West Germany the Nazi abortion laws were relaxed, but “while compulsory abortions and sterilization ceased in May 1945 due to nullification of Nazi laws, the elective abortion of fetuses continued apace from the first months of 1945 and over the course of the year became a mass phenomenon” (

Fehrenbach 2009, p. 35). While the rational of the German medical board that made the decisions over abortion requests shifted from a discourse of racial purity, approval was still influenced by anti-Black conceptions of emotional health.

Fehrenbach (

2009) found there was a shift from the focus on the purity of the offspring to a concern for the emotional state of the mother, and, specifically, a “transition from an emphasis on the biology of race to the psychology of racial difference” (

Fehrenbach 2009, p. 36). German women who desired to have an abortion, even in the instance of White GI rape, could be denied because the gynecologists that staffed the medical boards could find no reason for concern for the woman’s physical or mental health because the white offspring would easily be integrated into the white German social body (

Fehrenbach 2009). Circumscription of the rights of German women was still understood to be a state interest and the medical, legal, and social apparatus’ that made reproductive health care available (or not) for German women were guided by an anti-Black ideology that disproportionately punished relationships between German women and Black men.

While it appears, Anna could have ended her pregnancy if she would have publically stated the birth father was part African American she did not. Anna continued with the pregnancy. “My mother asked me if I was pregnant. I said, ‘how should I know?’ I continued to go about my life and work until I went into labor. I never sought medical care for the entire pregnancy. When I went to the hospital I asked, ‘what did I have, a boy or a girl?’ I was absolutely shocked when the nurse told me, ‘twins! Twin girls!’” (Anna, personal interview) (see

Figure 6).

According to the adoption social worker notes, Anna wanted to give away the twin babies immediately, but was prevented by her mother, the matriarch of the family. “My mother said nothing (about me giving birth). She was so happy to have the babies. When I tried to give the girls up for adoption she said no. ‘They’re family. Family stays with family’.” When I asked Anna about her father, my great grandfather and his reaction to the children, she said, “he had no reaction. He was no longer with the family, since my (youngest sister) was five years old” (Anna, personal interview).

The young infants remained with Anna’s mother and her sisters being the primary caretakers of the girls since Anna went back to her life of working two jobs. However, the cramped apartment eventually became too crowded with four adults and two babies. “Family may stay with family,” but that did not mean everyone got to live with family fulltime. Once the twins were old enough, they were moved into a dormitory-style dwelling with many other White and

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder which was run by a Catholic organization. The dormitory-style living/orphanage quarters operated much like a boarding school where parents visited their children during the week, and some of the children stayed in the family home on the weekends. Some of these children were adopted out of these organizations and others not--it depended upon the desires of the mother. These orphanages were popular outlets for all

Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder. For example, in 1954 in Imst, Austria, the “Neue Deutsche Wochenschau newsreel clip showed an idyllic children’s village… full of orphans and children, making the institutionalization of the children with orphans and abandoned children look attractive” (

Sollors 2014, p. 223). The social work paperwork as it concerned my mother and her twin varied drastically with some data putting them in a German Catholic Orphanage at 18 months old and some as late as 3 years old, but, according to those records, they lived in the orphanage with “70 other children (which had) dormitory-type living and on-site schooling. My mother was “particularly fond of two nuns” when she lived at the German Catholic Home, but her “birth mother and maternal aunts visited frequently” (Social Worker notes, Children’s Home Society of California speaking to my mother in 1958, received access to these sealed documents in 2012).

Regardless of this age disparity (either 18 months or 3 years old), all seemed relatively stable and routine for the twins; they were part of two families; the nuns who ran the living quarters/orphanage and their biological family. The twins were integrated into their family, knowing biological family members and family members babysitting for Anna when they were not in the dormitory and she was at work. As Anna stated about parenting her daughters, “I didn’t really raise you; (my youngest sister) and my mother raised you (and your sister). I was always at work.” However, there were special moments shared between mother and daughter resulting in pair bonding quality time with their mother that is crucial to the mother-daughter relationship. “Once when you were a little girl, maybe two years old we went out to a restaurant. You wandered around the restaurant and the next thing I know you were no longer around. You were lost. I lost you. I had everyone looking for you in the city. We never found you. You found your own way back. I was so afraid.” Another special mother-daughter outing in Germany was referenced: “You were four years old. One day I picked you up after work. It was just you. We really liked that. (Your sister) was not with us because she was being punished because she had cut a little girl’s hair in the orphanage; cut the girl’s braids off! So her punishment was not being able to come out with us and no Christmas gifts. Therefore, I picked you up in the morning and returned you (back to the dormitory) on Sunday night” (Anna, personal interview) (see

Figure 7).

In these storied moments, there are memories recounted where it is clear there are conflicted moments for Anna about being a mother. On one hand there is some motherly attachment and love for the twins, and on the other hand resentment as it concerns her drastic change in lifestyle as she was forced to parent two children she wanted to adopt out immediately, but her mother would not allow it. Having choice, power, and agency removed from her since it was her mother who told her she could not give away the twins for adoption, Anna made a drastic decision: she left. She said something was said, something horrible, something racist that Anna refused to give voice to; “there are some things that you don’t speak about, but just hangs over you” (Anna, personal interview). Whatever was said, through the interviews I have discerned it was something that was said by her middle sister, the same woman who refused to see me when I was visiting Germany in Summer 2014. Anna pre-arranged international sponsorship and passage to the United States in 1955, becoming one of many immigrants to go through Ellis Island on her way to California. Like a fugitive, she left her seven year old twin daughters in Germany to be raised by their grandmother and her sisters. Anna told no one she was leaving or where she was going. She left. Later, she contacted her youngest sister telling her that she was safely ensconced in the U.S. sans her biological children, embracing the freedom she had once lost (see

Figure 8).

4. Mixed Race: Skin Color Matters

“Why do I look so different from everyone else?” asked my mother at age four to beloved Sister Melissa, a nun at the orphanage. “We are part of nature; look around. There are no two trees or two flowers that look alike. Everything in nature is different.”

(My mother in 1952)

Anna was free from her children for several months in 1955, living a life where the label “mother” did not define her. Anna gained sponsorship to the U. S. from Frank and Josephine Duveneck, a couple who founded the Hidden Villa Ranch. Anna began a new memory, that of an immigrant. In the months Anna was in California on her own, the twins, on the other hand, had a life in Germany that consisted of dormitory living, family visits on the weekend, and school. Like all German children, these twins who lived a life more akin to a boarding school, were fully integrated to German life, held German citizenship, and were given the last name of their German mother. The twins had friends and friendship networks and knew their family members: aunts and grandmother. They were, despite living in an orphanage/boarding school, family, just the way my great grandmother wanted. However, in the financially difficult times during the post-war rebuilding era, the children were, after all, Anna’s responsibility. While the family struggled in Germany, Anna lived an unencumbered life in the United States without her children. The grandmother who said “family stays with family,” was apparently undermined when, unbeknownst to her, she discovered that Anna worked with the nuns at the orphanage to have the put the twins on a plane to the United States. Their first plane ride, which was full of other German children (White and children of Color from orphanages around Germany many of whom up for adoption) had them eventually landing in California and somehow on Anna’s doorstep in 1955.

Thankfully, the Duveneck’s provided Anna a home and a home and stable living environment for the twins for three years, from 1955–1958. The freedom that Anna had, a life as a single person free from the responsibility of children, evaporated and the memory and the reality that she had to be the sole breadwinner haunted her. Luckily, in the time she was on her own, Anna had found a full-time office assistant job with a large firm and the Hidden Villa Ranch was big enough to house Anna and the twins nine months out of the year. Since the ranch was a working ranch, hostel, and summer camp, during the summer months Anna had to vacate her living quarters to paying renters, but the twins were allowed to remain since they joined the summer camp. Thus, three months out of every year for three years Anna lived a transient life, sleeping on the floor, in the spare bedrooms of friends, or in makeshift apartments above garages. Still a German-speaking household, and knowing very little to no English, Anna was the world for the twins. Eventually, the Duveneck’s (also German speakers) had come to love the twins as if they were their own children and “they wanted to adopt the girl’s but I said no” (Anna, personal interview). It was curious that Anna passed up an opportunity to be free of her twins since she had wanted to have the twins adopted out immediately after they were born. Based on the interviews with Anna, her mother, my great grandmother, was the largest barrier to her ability to adopt the twins out. Anna refused to answer why she did not want this German family (a family Anna and the twins loved) to adopt her children. However, the sudden death of Anna’s mother in 1958 opened up a world of possibilities for Anna and the twin’s lives were to be permanently upended.

Anna met a White man. The man she met was divorced with children of his own, whom he did not have custody of upon the divorce from their mother. She met him at her work and this would-be bachelor entered the lives of the twins. “He was instantly smitten with me. I asked around about him and learned he was divorced with two daughters, but the daughters lived with their mother” (Anna personal interview). The twins spent time with the man and they were a little family. “We did family outings together and he even “read us bedtime stories” and tucked them into bed (Mom and Anna, personal interviews). He “always accepted me and accepted my past. He never held that against me. He didn’t mind that I was not a virgin” (Anna, personal interview). However, then for some reason she and her boyfriend broke up. “I was devastated. I couldn’t be a single parent again” (Anna, personal interview). Whatever caused the breakup, Anna would not say. In this recollection, what is primary is that the “past” becomes an enthymeme or coded, unspoken word for children out of marriage and Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder at that. The sexual expectations and requirements for women to remain chaste until marriage was one that according to societal definitions, she violated. To escape this face-shaming event, she left country and home and traveled to a world where no one knew her, sans the Duveneck’s who sponsored her and eventually knew her personal story when the twin girls were literally placed on her doorstep. Birthing the children was an event that Anna described to both my mother and me as “awful, the worst day of my life” (Anna, personal interview).

How long the breakup lasted was never said during the interviews, but in May 1958 they reconciled after he proposed. The man who was smitten with Anna proposed and she found herself accepting marriage with this man on his terms: I’ll marry you, but I don’t want another man’s children. Anna conceded. Learning about the engagement the Duveneck family once again offered to adopt the twins, and once again Anna turned them down. Instead, she announced to the Duveneck family that she and her fiancée had begun parental rights termination paperwork which they had already filed with the court; the twins were going into the California orphanage/foster care system. Furious, the “Duveneck family never spoke to me again. They never forgave me” (Anna, personal interview). The parental rights termination papers were finalized in July 1958 and Anna was a married woman October 1958. “We wanted to begin anew like any newly married couple” (Anna, personal interview). The ten year old twin girls were not invited to the wedding and Anna had begun to make new memories of her new life as a married woman with no children in her new home with her new husband. Her new life as a married woman included the ability to live a wealthy lifestyle where she did not have to work, and came complete with a once-a-week housecleaner and gardener. Her new lifestyle afforded them the ability to travel and he retired early so they could enjoy the kind of life they wanted to live together as a couple. In the creation of these new memories with a new life, the children were an afterthought whom “she would visit monthly” to take them out “for dental appointments and ice cream,” and she also provided them “a living allowance at the orphanage” so they “would have spending money for desserts or whatever we wanted” (Mother, personal interview). In memory of the twins, she planted a tree in her new yard and around the base of the tree placed two abalone shells containing artificial flowers. At 10 years old the twins were stripped of another stable environment, stripped of their German citizenship, and became wards of the state in July 1958.

14 The twins were fully ensconced in the California orphanage system. The Children’s Home society placed them in Ming Quong in Los Gatos, California (see endnote 11).

5. Rejection: Suddenly Not German

Your sister had a light complexion, a round fat appearing face and kinky textured light brown and blond hair. She related easily, was outgoing and succeeded in being the leader…. (There are language barriers for both but) she is brighter and has a rosy cast. She describes herself as an American and a German, but (prefers to call herself) an American... She seems to be coping with the recent information that her birth father was of Negro (sic) descent. You (on the other hand) had dark brown hair and a medium to dark complexion, thick lips, a long narrow face, and less kinky textured hair. You were seriously thoughtful… (but) a slow learner…. You seemed to be well liked and accepted... but slow to be a leader. You are stubborn…. You had recently been told of your part Negro (sic) heritage and [instead] reported you were German. You often mention your birth mother…. You draw pictures of your birth mother.

(Social Worker, Children’s Home Society of California)

Starting over is a privilege afforded to few. My mother chose not to start over and suddenly claim that she was “Negro” or American, but rather German to the chagrin of the social worker. My mother claimed the identity, language, and heritage she knew, German. Anna on the other hand, chose to start over. Anna had the privilege to create new memories. Anna had the privilege to begin new narrative experiences. The relinquishing of parental rights by Anna was a do-over for her. Without children from a failed relationship she was able to begin anew. As she was re-inventing herself as a 36 year old newlywed, my mother and her twin were reeling from loss of language, culture, citizenship, country, home, and now family. The official documents from the social worker, at times vary drastically from the recollections of my mother and Anna, and her sisters, but one theme is prominent: the twins were a burden who had to go, in particular because of their new status—“Negro.” In the United States, the one-drop rule was law. According to the one drop rule, “one-drop of Black blood” makes one Black. To be classified as Black under the one-drop rule, a person’s lineage had to be 1/32nd or more Black in ancestry. In other words, if someone had a Black relative in their genealogy as recently as five generations ago, then that person would be classified as Black under the one-drop rule and, therefore, not a beneficiary of Whiteness and all of the privileged notions that come with being White. Suddenly, the twins are deemed to be “Negro” and all of the negative phenotypical associations that come with that: slow wit and intelligence, thick lips, dark skin and kinky hair.

There was a great deal of sympathy by the social worker for Anna who was saddled with two “mistakes” she had taken care of for ten years and the worker was impressed by her success despite these challenges.

(Anna) had a definite accent and good command of the English language... She had a very fair complexion... and is attractive and capable... She had considerable insight and knew the importance of working through her feelings of past experiences... She had the equivalent of two years of college... She was a manager in (Germany) and supervised all employees…. She earned a very good salary... and appeared to have above-average intelligence.

(Social Worker, Children’s Home Society of California)

The social worker’s representation of Anna is very inconsistent with how Anna characterized her class positionality in Germany. Perhaps Anna told different memoried stories depending on the circumstance, thus emphasizing her working class struggles when justifying her casting off of her children in Germany and emphasizing her middle class identity when seeking affirmation in the United States. The different narratives told illuminate how she crafted her now-immigrant story of survival. Because of this story of survival, Anna, is afforded all of the benefits of Whiteness, including beauty and intelligence; apparently attributes that are synonymous with Whiteness. The children, on the other hand are the anchors that hold her down, preventing her from accessing White privilege.

As the social worker notes mention, the downward spiral in her life came when two biracial babies were born. According the social work records, the family had trouble accepting these Afrodeutsche Nachkrieg twins, Anna’s mother in particular, and she asked Anna to move the babies out. “Your maternal grandmother ... had difficulty accepting your racial diversity and requested your birth mother find another home” (Social Worker, Children’s Home Society of California). This social worker quote contradicts the historical memoried narrative Anna shared. Anna wanted to immediately give the children up for adoption. Anna’s mother was the roadblock, thereby, forcing her to keep the twins. Further, Anna lived in the family home during the pregnancy and after; only the twins were displaced into the dormitory/orphanage in Germany. Again, the only narrative is the one being delivered by Anna to social workers. There are no other adults who can cast doubt on the memories and experiences she shared, and the children have no credibility. It can be argued that Anna manufactured accounts for various audiences to fit hegemonic norms in order to assimilate more easily in the U.S. The disparity between the two accounts can be due to a number of situations that involve a four-pronged approach: shame and face-saving. (1) There are a number of “hard luck” immigration stories that one uses in order to gain entry into a new country. One of the foundational narratives in America is the “Horatio Alger myth” or pulling oneself up by their bootstraps. In the zeal to assimilate more easily into a new nation, accessing and using that nation’s stereotypes and prejudices in one’s favor aids in acceptance into the majority culture. (2) Admitting that you failed. This results in a loss of face. One is unable to measure up to the normative standard of what and who a good mother should be. Therefore, you must give yourself the saddest backstory possible in order to evoke an emotional (pathos) appeal. (3) Admitting that you not only failed, but also that you violated societal normative standards as it concerned virginity. You have evidence that you were a “naughty” or “bad girl” and for you lack of virginal attributes children are your punishment. In order to circumvent this loss of face and shame, you must show evidence that you are working hard to change your course. The most dramatic evidence of changing one’s life is to let go of what is weighing you down, in this case, children. In addition, (4) admitting that you violated societal standards regarding sexual relations potentially with a “Negro.” There was no greater sin a White woman at that time could have engaged in—sexual relations with someone who was not White. Anna violated these normative standards. The social workers response to her situation, “(Your mother) married another and although she hoped to care for you after the marriage, she found it emotionally difficult to cope with the social intolerance of your bi-racial heritage and felt it interfered with her relationship with you… (On the day she relinquished you) she met with you sensitively and sweetly and said her final goodbyes. She was emotional and this seemed to have meaning for you” (Social Worker, Children’s Home Society of California). One has to wonder what Anna was thinking if she believed the U.S. would be a paradise for Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder given all that was happening as it concerned civil rights in the 1950s and early 1960s; e.g., sit-ins, demands for voting rights, fight to end Jim Crow, 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, 1955–1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott. Clearly, she may have seen the move to the U.S. as more beneficial for her, because at the very least she was afforded with the opportunity to begin anew and make new life memories.

The above account from the social worker differs drastically from both the accounts of Anna and my mother, but face-saving for Anna is in action and evident in the written record. The memory Anna shared of her leaving and severing her parental rights vacillated from naiveté to face-saving to honesty. Naiveté: “I thought if you were unhappy in your new home you would be returned to me. That’s what the adoption agency said. They refused to give you back to me. I was threatened with arrest if I took (you girls) back.” Face-saving: “I did it so you could be in a home that was financially stable, but I hung around the area just in case you decided to come back.” Honesty: “The day that I found out I was pregnant was the worst day of my life.” Already at Ming Quong, by the time the goodbyes took place, after Anna, was already married with a secure and stable life, she said goodbye to the twins. The goodbye my mother remembered was also the complete antithesis of the goodbye that the social worker noted:

I thought it was a visiting day. We were sitting outside on a bench at Ming Quong. My mother was very stoic. There was no handholding and no conversation. No motherly loving exchange. It was just ‘let me get this off my chest and let me go.’ My mother said, ‘You know I am not coming back. This is the last time we are going to see each other.’ I stared at her, trying to read her. My reaction was ‘she doesn't mean that. It couldn’t be that.’ She always visited us in Germany and in Ming Quong. Then she left. Unbeknownst to us, she had already married and begun a new life.

(Mother, personal interview)

Maybe as an adult Anna was emotionally distraught and could not say anything without crying. Somewhere in the depths of the memory, in the boughs of reality and fantasy, lies the truth. The disparities in the goodbyes, regardless, result in the same action, adoption. In 1960 at the age of twelve my mother and her twin were adopted by an African American family who both twins referred to as “emotionally and physically, and sexually abusive.” Anna was 38 years old, married, and in a financially well-off, stable home environment by the time the twins were adopted. The justification for having the twins adopted was that the children were unwanted and that they would be adopted by an African American family, thus eliminating the “race” issue, particularly for Anna.

6. Reunion: A Revival of Memory

Fifty-two years later, a reunion between mother and daughter occurred. Upon learning that my mother and I located Anna after a two-year transcontinental search, my mother’s twin’s reaction was to weep uncontrollably for five minutes. Afterward, my mother’s twin was emotionally exhausted, but put together the remnants of their childhood photographs so my mother would be able to share the memories she had, as well as prove who she claimed to be; one of the daughters adopted out of the German family. Anna’s first words were, “I always hoped you’d forgive me” (personal interview). My aunt (mother’s twin) chose not to have a relationship with Anna given all that had transpired over the decades. My mother, on the other hand, visited once, talked of a second visit, and spoke weekly with her mother since they were reunited in 2012; I visited twice and spoke on the phone with Anna, initially weekly, and then often my calls went unanswered and unreturned. Forgiveness in memory is often unnavigable terrain that takes years to process. How does and should one forgive a less than ideal childhood? This article is part of a book in progress about Afrodeutsche Nachkriegskinder that examines such reflections using my family as the primary exemplar. In the fifty-two years that transpired, my mother and I saw and learned about a life, a woman’s life, and her choices that had not taken us into consideration since 1960.

Anna “had a quiet life” with her husband and remained close with her youngest sister (the sister who primarily babysat the twins when Anna was at work) (Anna, personal interview). Anna lived vicariously through her youngest sister’s life as it concerned watching her niece and nephew, never missing a milestone, and watching them grow into adults and see her nephew have children of his own (the niece died). She remained devoted to her nephew’s children as evidenced by the pictures of them throughout her house. The pictures we sent were placed on the bookshelf in an unmarked photo album found at the bottom of a large stack of books. To this day, the extended family knows nothing about my mother and her twin and they have no idea that Anna had children. By all public appearances Anna never had children. Everyone was told that she was unable to have children. Moving from a public narrative that included the inability to have children to one where the daughter and granddaughter show up on the doorstep is quite a cognitive dissonant moment. How does one navigate that public narrative? How does one circumnavigate a memoried event that when one digs a little deeper, falls apart?

7. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: A Mixed Race German Granddaughter

Our reappearance, my appearance in Anna’s life is the post-memoried event that topples her reinvented immigrant story. On 13 July 2012 my mother wrote a simple, but detailed account of her life and who she was and sent it to Anna. When Anna opened the letter she said she “collapsed on the floor. I could not believe it.” While my mother had nearly twelve years with Anna, I had none. Suddenly I might gain a grandmother. Initially weekly phone calls began and early on we made plans to visit Anna six weeks later here in the U.S. Talking with Anna completes a circle I began as a child where, anytime I was in Germany, I would try and locate her by looking her up in the telephone book and ringing up all of the people with her last name. Plans for Anna and her husband to pick us up at the airport were made, so rather than merely describe myself I sent pictures of myself and my husband, and my mother did the same thing. Anna said our pictures were on her end table in her living room, but she was evasive about whether or not we would meet any other German relatives living nearby. When it was closer to us visiting, after she received our pictures, suddenly the offer to pick us up from the airport was rescinded, and instead we were told to rent a car and find the directions to their house online. I thought the change was curious, but they are elderly, so I tried not to read much into the situation.

It was difficult reaching Anna on the phone to let her know we had arrived and were at the hotel. We waited 8 hours to hear from her. Our reunion was something resembling those on

Oprah, and was full of hugs, kisses, smiles, and included my great aunt (Anna’s youngest sister) and her husband. We patiently spent hours (and ultimately four days) looking through her photographs filling in the gaps we had of her life, her experiences, her memories with her sisters and nieces and nephews. Pictures were all over her house, including a picture of Olympic gold medalist gymnast Gabby Douglas, but ours were nowhere to be found. We were strangers and she was showing us the accomplishments of a life lived. Later, I learned our pictures, unlike the Olympic gold medalist, were buried at the bottom of a wall-length bookcase under huge stacks of books. I sent other pictures later, but those too were never displayed. Upon the sharing of her life story, the family genealogy book, our

Familienstammbuch that traces my family’s German heritage back to the 1800s was shared.

15 The

Familienstammbuch was snatched away by my great aunt (the youngest sister who babysat the twins when they were infants) and I was told by her, “that book is only for family!” I told her, “I’m family.” But to her I was not. The last two pages of the

Familienstammbuch were reserved for Anna to enter her daughter’s names, birth date, baptism, dates of marriage etc.... into the book. She never did.

As a child I imagined a life for Anna; I made up memories for her that included her being a wealthy princess who pined for her twin daughters. I had fantasies that she and I would be inseparable best friends and she would introduce me to her entire family, my family, and they would instantly love me, but that never happened. My mother, her twin, and I are invisible, because our presence makes for an inconvenient narrative. During the first reunion and during subsequent phone calls and Skype calls, and in-person visits with Anna and my great aunt (Anna’s youngest sister) I continually asked for a full family reunion, but was constantly told by my great aunt, “no, now is not the time. Let’s see how this turns out and how we all feel about one another and maybe we will have a family reunion” (personal interview). Since 2012, there have been family reunions, family cruises to exotic locales, and family vacations, but not one that ever included the twins and their family. The twins, and me as the only grandchild, are stuck “in the closet.” Our identities are not marginalized or disenfranchised, but erased. I contacted other family members I found on Facebook and sent pictures of our reunion, only to be met with stony silence. What I know of Anna’s life I know through a lens that does not include me and has not included my mother and her twin for 52 years. Anna, and the rest of the German family, are choosing to ignore and erase us. When I pushed why, why are we erased Anna, fatigued with my questioning said, “you can’t force relationships.” I pressed further and she yelled, “Because we’re embarrassed! I’m sorry I have such a crummy family. To me people are people.” The embarrassment and erasure continued at Anna’s funeral in 2015; when Anna died the twins and I were not allowed to attend the funeral and initially were told that there was not even going to be a funeral. The fear of what others would say, coupled with the vast wealth the other family members inherited were the driving factors. How does one explain away twin girls and a mixed race granddaughter when the life-long narrative has been that Anna had no children?

8. Conclusions

This research is part of a larger book project, where in that project, the search for more voices, in addition to those of my German family, are sought after. The difficulty of this project is that the data involves closed international adoptions from the 1940s and 1950s and hoping that the mothers and fathers are (1) alive and (2) willing to talk about such a private, and for some an embarrassing and/or painful moment in their lives. Efforts are underway to have a larger dataset that exceeds the boundary of authoethnography in an effort to include more voices and extend the boundaries of the current literature on memory and post-memory. However, what this research shows is that the actions one takes in their life can have a ripple effect that can affect others minutely or drastically.

What does it mean to bring in concepts of trauma and repetition? My mother and her twin were left twice; first in Germany and then at an orphanage in California. I am the one who pressed to open the door for the trauma of abandonment to be repeated a third time. My mother’s and her twin’s life is hardly emblematic of a Disney fairytale, but is unique because few children from post-war Germany who were adopted internationally find their biological parent(s). My family’s situation is more unusual because the children were twins and the children were adopted later in life, as pre-teens who are able to remember and tell their own story. As young adults who were adopted as opposed to infants and toddlers, the twins have their own memories about their mother and their German family. Having their own first-person accounts to these often marginalized, disenfranchised, and erased memories is rare. What binds our three generations of women together? Why did Anna and her youngest sister open that door and agree to meet us, but yet insist that we remain invisible? Would we have been asked to “stay in the closet” if we looked more like proper blond haired, blue-eyed Germans with white skin? Anna’s skin color was alabaster; the twin’s skin lightened as they got older and with their hue more of a very pale white color. Further, while my mother’s hair remained brunette in color her twin’s hair turned blond. Knowing these phenotypic changes, I challenge that race is the only factor as to why the twins and I are to remain invisible to the majority of my German family. The link of societal shame coupled with gendered expectations of women at that time and race must be further examined. However, does societal shame supersede racism?

Interestingly, it is appears that my great grandmother seemed to be much more open-minded to the birth of the twins. I imagine my great grandmother struck with grief at the thought that her grandchildren we suddenly removed from her life altogether when Anna had them put on a plane to the United States without telling any family members. Anna’s first instinct, on the other hand, was to adopt out the twins immediately after giving birth. To Anna, the twins were tainted by shame and what White German society would say about white-colored twins who had the invisible mantle of Blackness. Anna so feared being trapped by the role of motherhood and her sexual shame that she ran away and immigrated to another continent (temporarily without her twins) and restarted a post-memoried event she could safely present to White U. S. society. The only hitch in her concocted narrative was her “guess who’s coming to dinner moment” twice; once when the twins reemerged in her life in California, and once when my mother and I (the mixed race Black German granddaughter) arrived on her doorstep. While the reunion was largely pleasant resembling an Oprah-esque moment caught on film, it was not supposed to be a reoccurrence where we all lived together happily ever after; our visit was supposed to be a dip in and dip out of one another’s lives. The knowledge that we found one another, saw one another, and we were all happy and healthy was supposed to be enough.

Perhaps it is curiosity that led Anna to contact us after she received a letter from her daughter 52 years later; does Anna’s memory of events match up to her daughter’s, to mine? Maybe there is a desire to see if there is a tie that binds all of us together, that goes deeper than a biological connection, but a desire to see what has become? Maybe in finding one another we will be better able to understand ourselves a little bit better. Perhaps the desire to meet one another is the first step toward forgiveness and building new memories, less painful memories. Upon meeting Anna for the first time, I realized that all three generations have the same nose and similar facial features. Memories of significant events in life become representative of a larger whole, a whole that goes beyond one family and references a larger narrative about Germany, WWII, race, and citizenship post-WWII.