Cutaneous Protothecosis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

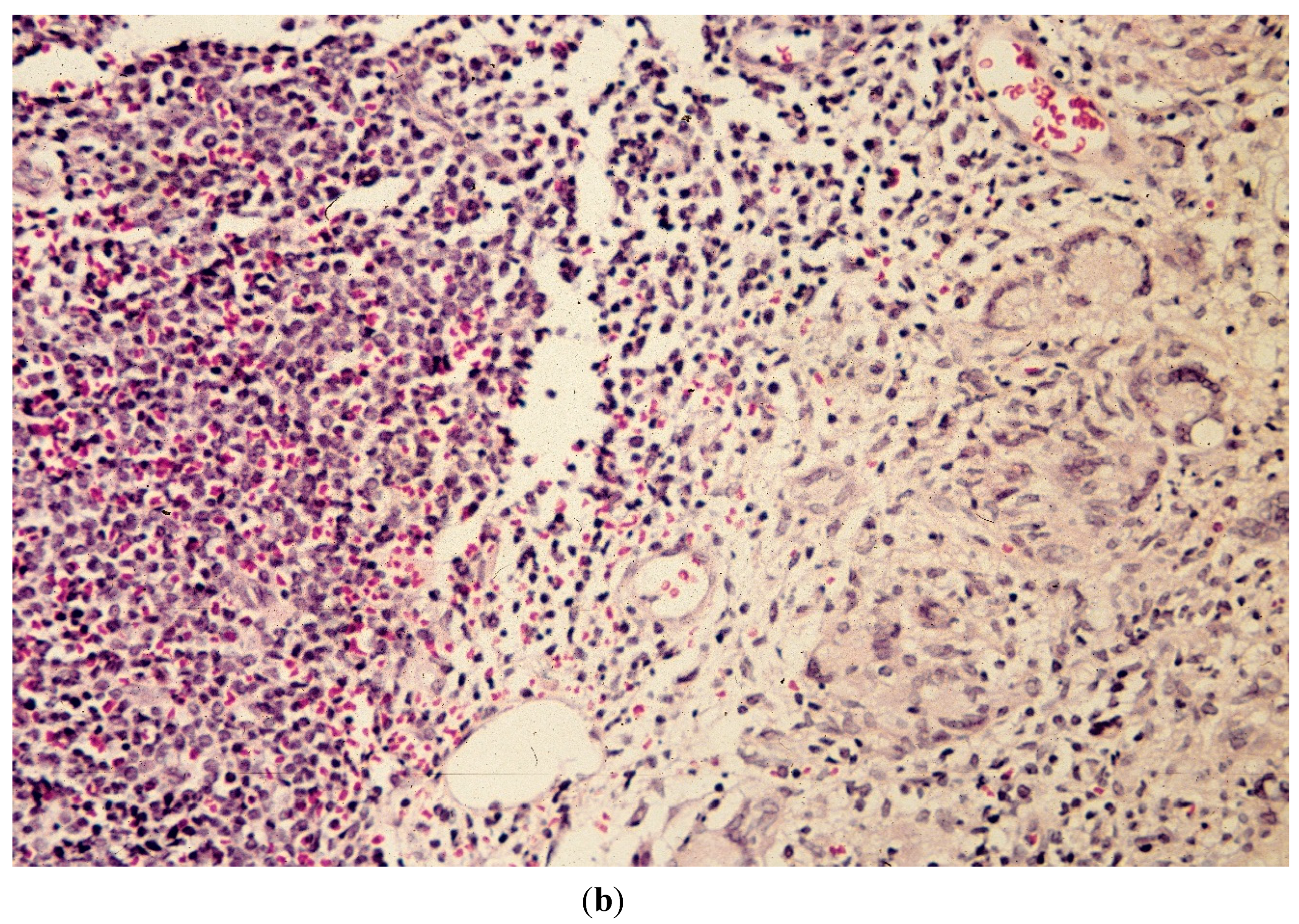

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iacoviello, V.R.; DeGirolami, P.C.; Lucarini, J.; Sutker, K.; Williams, M.E.; Wanke, C.A. Protothecosis complicating prolonged endotracheal intubation: case report and literature review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992, 15, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass-Florl, C.; Mayr, A. Human protothecosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, I.D.; Sacks, H.G.; Samorodin, C.S.; Robinson, H.M. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Arch. Dermatol. 1976, 112, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.Y.; Lo, K.K.; Lam, W.Y.; Fung, K.S.; Koeler, A.; Cheng, A.F. Cutaneous protothecosis: A report of a case in Hong Kong. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 133, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, S.; Martinka, M.; Lui, H. Cutaneous protothecosis following a tape-stripping injury. J. Cutan Med. Surg. 2009, 13, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, C.; Wakusawa, C.; Chikama, R.; Murakami, K.; Hitomi, H.; Satoh, K.; Makimura, K.; Hiruma, M. A case of cutaneous protothecosis in a polyarteritis nodosa patient and review of cases reported in Japan. Dermatol. Online J. 2011, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woolrich, A.; Koestenblatt, E.; Don, P.; Szaniawski, W. Cutaneous protothecosis and AIDS. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 31, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, C.M.; Silva-Lizama, E.; Logemann, H. Human cutaneous protothecosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1995, 34, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.P.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Zhu, J.H.; Zhu, M. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient with diabetes mellitus and review of published case reports. Mycopathologia 2012, 173, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayhall, C.G.; Miller, C.W.; Eisen, A.Z.; Kobayashi, G.S.; Medoff, G. Cutaneous protothecosis: Successful treatment with amphothericin B. Arch. Dermatol. 1976, 112, 1749–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.T.; Hseuh, S.; Wu, J.L.; Wang, A.M. Cutaneous protothecosis: A clinicopathologic study. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1987, 111, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Monopoli, A.; Acceturi, M.P.; Lombardo, G.A. Cutaneous protothecosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1995, 34, 766–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.T.; Suh, K.S.; Chae, Y.S.; Kim, Y.J. Successful treatment with fluconazole with protothecosis developing at the site of an intralesional corticosteroid injection. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 135, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otoyama, K.; Tomizawa, N.; Higuchi, I.; Horiuchi, Y. Cutaneous protothecosis—A case report. J. Dermatol. 1989, 16, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tyring, S.K.; Lee, P.C.; Walsh, P.; Garner, J.F.; Little, W.P. Papular protothecosis of the chest. Immunologic evaluation and treatment with a combination of oral tetracycline and topical amphotericin B. Arch. Dermatol. 1989, 125, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phair, J.P.; Williams, J.E.; Bassaris, H.P.; Zeiss, C.R.; Morlock, B.A. Phagocytosis and algicidal activity of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils against Prototheca wickerhamii. J. Infect. Dis. 1981, 144, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venezio, F.R.; Lavoo, E.; Williams, J.E.; Zeiss, C.R.; Caro, W.A.; Mangkornkanok-Mark, M.; Phair, J.P. Progressive cutaneous protothecosis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1982, 77, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carey, W.P.; Kaykova, Y.; Bandres, J.C.; Sidhu, G.S.; Brau, N. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient with AIDS and a severe functional neutrophil defect: successful therapy with amphotherin B. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 25, 1265–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, J.S.; Sober, A.J.; Rubin, R.H. Dermatologic manifestations of infections in immunocompromised patients. Medicine 1985, 64, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polk, P.; Sanders, D.Y. Cutaneous protothecosis in association with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. South Med. J. 1997, 90, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, F.A.; Passalacqua, J.A.; Kao, G. Disseminated cutaneous protothecosis in an immunocompromised host: A case report and literature review. Cutis 1999, 63, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hillesheim, P.B.; Bahrami, S. Cutaneous protothecosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2011, 135, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Xi, L.; Qin, W.; Luo, Y.; Lu, C.; Li, X. Cutaneous protothecosis: Two new cases in China and literature review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012, 51, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, J.C.; Ward, P.B.; Johnson, P.D. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient with hypogammaglobulinemia. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2013, 2, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, J.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.; Yi, S.Y.; Oh, H.E.; Song, J.S. Human cutaneous protothecosis: report of a case and literature review. Korean J. Pathol. 2013, 47, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.C.; Costa e Silva, S.B.; Lima, R.B.; D’Acri, A.M.; Lupi, O.; Martins, C.J. Cutaneous protothecosis—Case report. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, K.; Tee, S.I.; Ho, M.S.; Pan, J.Y. Cutaneous protothecosis in a patient with previously undiagnosed HIV infection. Australas J. Dermatol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.K.; Ham, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.H. Cutaneous protothecosis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 41, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.S.; Langley, M.; King, L.E., Jr. Cutaneous manifestations of Prototheca infections. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1995, 32, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follador, I.; Bittencourt, A.; Duran, F.; das Gracas Araujo, M.G. Cutaneous protothecosis: Report of the second Brazilian case. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop Sao Paulo 2001, 43, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, Y.; Hamaguchi, T.; Teramoto, T.; Takiuchi, I. A human case of protothecosis successfully treated with itraconazole. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 2001, 42, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, S.C.; Hsu, M.M.; Lee, J.Y. Cutaneous protothecosis: Report of five cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 146, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitanis, G.; Nomikos, K.; Zioga, I.; Velegraki, A.; Bassukas, I.D. Multifocal cutaneous protothecosis in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome. Hippokratia 2012, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamada, N.; Yoshida, Y.; Ohsawa, T.; Takahara, M.; Morino, S.; Yamamoto, O. A case of cutaneous protothecosis successfully treated with local thermal therapy as an adjunct to itraconazole therapy in an immunocompromised host. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors. Lcensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, Q.-G.L.; Rosen, T. Cutaneous Protothecosis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Fungi 2015, 1, 4-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof1010004

Nguyen Q-GL, Rosen T. Cutaneous Protothecosis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Journal of Fungi. 2015; 1(1):4-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof1010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Quynh-Giao Ly, and Ted Rosen. 2015. "Cutaneous Protothecosis in a Patient with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A Case Report and Literature Review" Journal of Fungi 1, no. 1: 4-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof1010004