Families’ Perspectives of Quality of Life in Pediatric Palliative Care Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Specific Aims

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Materials

- In two or three minutes, could you please outline for me the background/circumstances of your child’s medical condition that led you to begin receiving pediatric palliative care?

- In two or three sentences, Could you say a little about what “wellbeing”, “Quality of life” or a life of quality is to you?

- Please describe how you know your child is having a bad day.

- Please describe how you know your child is having a good day.

- How do you know that your child is doing well or poorly …Physically? Socially? Emotionally? Spiritually?

- Please reflect on the quality of life scales presented [participants shown PedsQL Comfort Care module. KIDSCREEN-25, and a drafted scale]. How would you improve them?

- Is there anything else you would like to talk about or that you thought about while we were talking?

| Expression: | ||||

| 1. How well did your child express him-/herself (in sounds, words, coos, moans, sighs, etc.)? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Tension: | ||||

| 2. How relaxed was your child? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Anxiety: | ||||

| 3. How much did the worry or stress in your child’s environment affect your child? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Energy: | ||||

| 4. How energetic was your child? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Social: | ||||

| 5. How engaged was your child with those around him / her (family, friends, professionals, etc.)? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Engagement: | ||||

| 6. How engaged was your child with things in his / her environment? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Negative Symptoms: | ||||

| 7. How intense have your child’s physical symptoms been (pain, fatigue, sleep issues, nausea, constipation, anxiety, etc.)? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

| Environment: | ||||

| 8. How positively-stimulating has your child’s environment been for him / her? | ||||

Not at all

| Slightly

| Moderately

| Very

| Extremely

|

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Participants

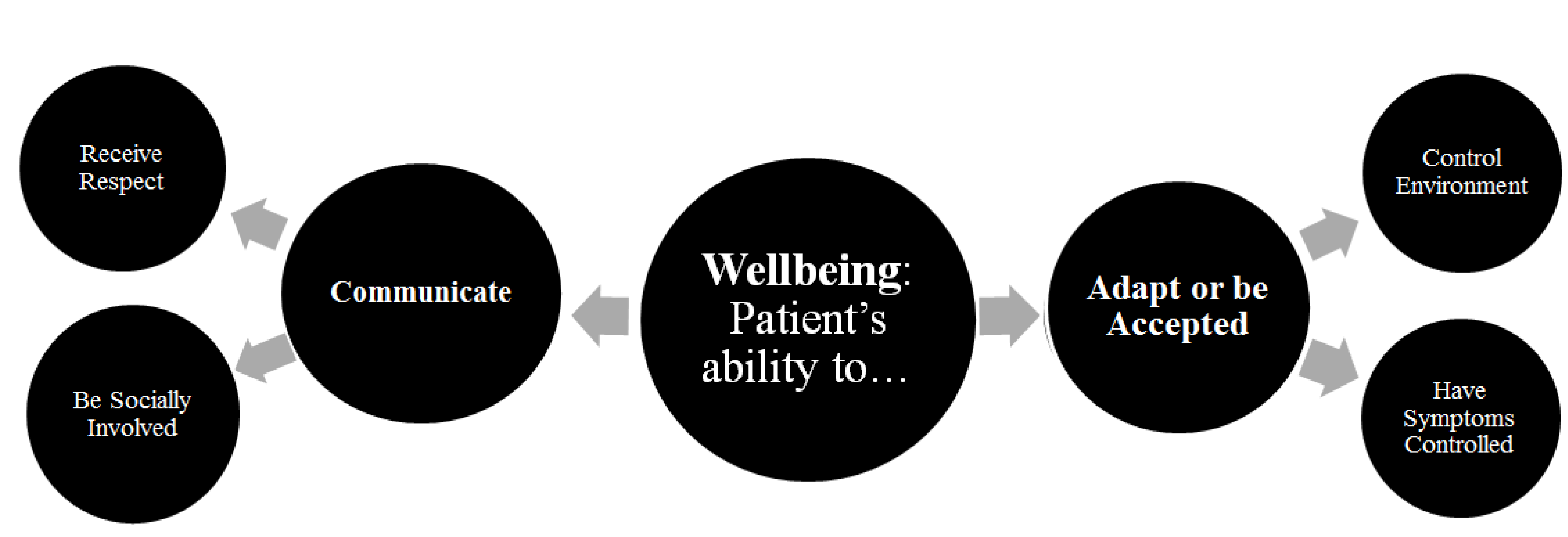

3.2. Themes Overview

3.3.1. Adapt or Be Accepted

When she’s unhappy and then you just kinda gotta go through her checklist and (.) okay is she wet (.) is she hungry (.) is it hot (.) is it cold (.) is it bright? …just kind of checklist of what she likes and what she doesn’t like until you figure out what it is that’s upsetting her and then she’ll calm down.

Some positive stuff: Does your child seem to be engaged um (.) responding positively to stimuli and again this (…) clearly focuses on you know measurable things you can judge that are more within the normal scale so it’s hard to shift for someone who is at the end of the spectrum.

We always believe that God’s plan and believe that life is a gi-gift … we have to you know do best … for our child (.) and when I came here I see reality about quality of life(.) I worked as a nurse (.) and I see a lot of cases of hospice like hop- hopeless cases… she’s at DNR right now (.) at first I said no? (.) no (.) I can’t (.) whatever I can do I’ll do my best to make her you know the best she could be (.) well right now I accepted the way she is (.) and seeing reality outside that there’s no quality of life then you know do your best but if it’s time for her to go then accept that.

3.3.2. Control Environment

He seems to really enjoy his daily routine (.) of going on the school bus going to school (.) and then see the day care friends after getting back on the bus and seeing his family in the evening (.) I think just sort of his social routine for the day.

We’re watching the [baseball] game (.) or we’re kicking back in the hospital room or waiting for food to come and he’s pretty relaxed (.) same day (.) the next day (.) we may have a procedure … there are so many other mitigating factors to what could cause that relaxation or that tenseness.

3.3.3. Have Symptoms Controlled

We don’t hold back on medication or anything like that when comes to him (.) with our other two daughters if they don’t absolutely need medication they don’t get it but with him (.) no (.) he takes all sorts of things … we don’t want him to have any pain any suffering in his life (.) I have no tolerance for him to have any pain ’cause he’s had enough already.

When her legs hurt (.) she won’t (..) come out and tell me all the time … what she’ll do is “Momma I don’t want to worry you (.) you know you’ve been through so much (.) I don’t want to worry you (.) I don’t want to tell you everything …” but I have been telling her “you have to don’t worry about me I’m here to take care of you” … she’ll just uh sleep all day (.) and then then about a couple of days later she’ll tell me “I was hurting my back was hurting” or you know “I couldn’t walk or good.”

3.3.4. Communicate

3.3.5. Receive Respect

It’s so easy for the doctor to come in … and just like: Stick those things in their mouth and look down her (.) and you’re just like “hey (.) hey (.) ask her could you do that” because when she ask her (.) she’s ready to open her mouth but when you just stick one little thing in there she’s gagging and he’s like (.) “What is goin’ on?” and she’s like “Hey (.) get out of my mouth”

I remember when we were first dealing with her … and I remember looking at that and that website and FML and I was like “are you kidding me?” “F--k my life” over these things? [laughter] and I know it’s kind of people complaining over just having fun with it but I was like you have no idea (.) [room laughs] anyway [sighs]

3.3.6. Be Socially Involved

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friebert, S. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care in America; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, F.; Lewis, M.; Lenton, S.; Poon, M. Planning for the end of children’s lives—The lifetime framework. Child: Care Health Dev. 2008, 34, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care, AAP. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- George Mark Children’s House: Where Hospital Meets Home. Available online: http://www.georgemark.org/ (accessed on 7 January 2013).

- Gans, D.; Kominski, G.F.; Roby, D.H.; Diamant, A.L.; Chen, X.; Lin, W.; Hohe, N. Better outcomes, lower costs: Palliative care program reduces stress, costs of care for children with life-threatening conditions. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. 2012. Available online: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7244h6wq.

- Children’s Hospital Central California. Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.childrenscentralcal.org/Services/clinical/Palliative/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed on 27 February 2013).

- Steele, R.; Davies, B.; Collins, J.B.; Cook, K. End-of-life care in a children’s hospice program. J. Palliat. Care 2005, 21, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, M.S.; Field, M.J. Measuring quality of care at the end of life. Arch. Inter. Med. 1998, 158, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. Pediatric health-related quality of life measurement technology: A guide for health care decision makers. JCOM-WAYNE PA 1999, 6, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, R.M.; Valentine, J.; Haynes, G.; Geyer, J.R.; Villareale, N.; Mckinstry, B.; Churchill, S.S. The seattle pediatric palliative care project: Effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.; Shenkman, E.A.; Madden, V.L.; Vadaparampil, S.; Quinn, G.; Knapp, C.A. Measuring quality of life in pediatric palliative care: Challenges and potential solutions. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, R.; Lau, A. Personal Wellbeing Index-School Children; Deakin University: Victoria, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Auquier, P.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; Czemy, L. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 european countries. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The KIDSCREEN-27. Available online: http://www.kidscreen.org/english/questionnaires/kidscreen-27-short-version/ (accessed on 23 March 2013).

- Bullinger, M.; Schmidt, S.; Petersen, C. Assessing quality of life of children with chronic health conditions and disabilities: A European approach. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2003, 25, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, D.C.; Kowal, S. Transcription systems for spoken discourse. In The Pragmatics of Interaction; D hondt, S., Östman, J., Verschueren, J., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2009; pp. 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaab, E.M. Families’ Perspectives of Quality of Life in Pediatric Palliative Care Patients. Children 2015, 2, 131-145. https://doi.org/10.3390/children2010131

Gaab EM. Families’ Perspectives of Quality of Life in Pediatric Palliative Care Patients. Children. 2015; 2(1):131-145. https://doi.org/10.3390/children2010131

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaab, Erin Mary. 2015. "Families’ Perspectives of Quality of Life in Pediatric Palliative Care Patients" Children 2, no. 1: 131-145. https://doi.org/10.3390/children2010131

APA StyleGaab, E. M. (2015). Families’ Perspectives of Quality of Life in Pediatric Palliative Care Patients. Children, 2(1), 131-145. https://doi.org/10.3390/children2010131