Turn on Fluorescent Probes for Selective Targeting of Aldehydes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. General Procedures

2.2. Materials

2.3. Absorption and Fluorescence Analysis

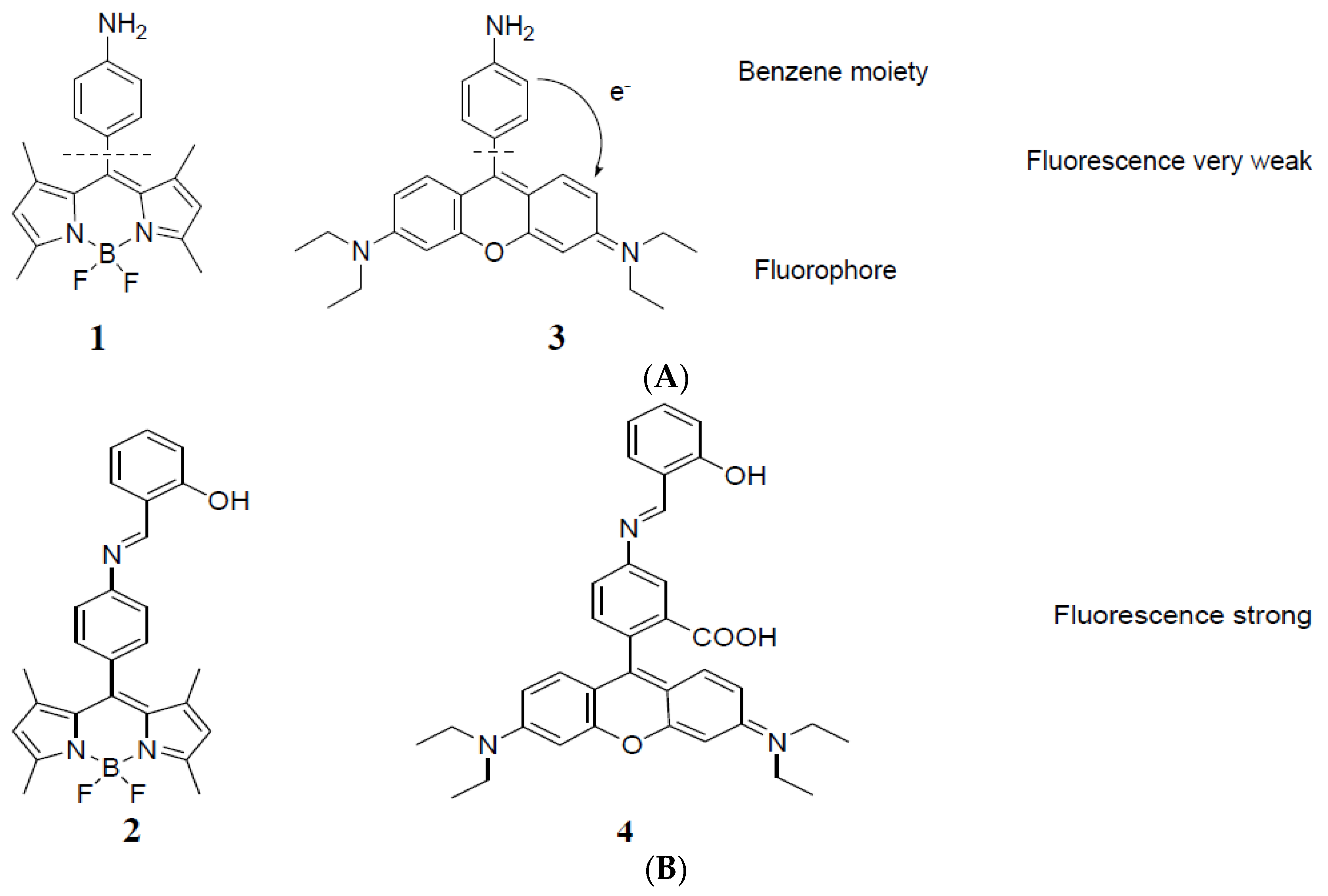

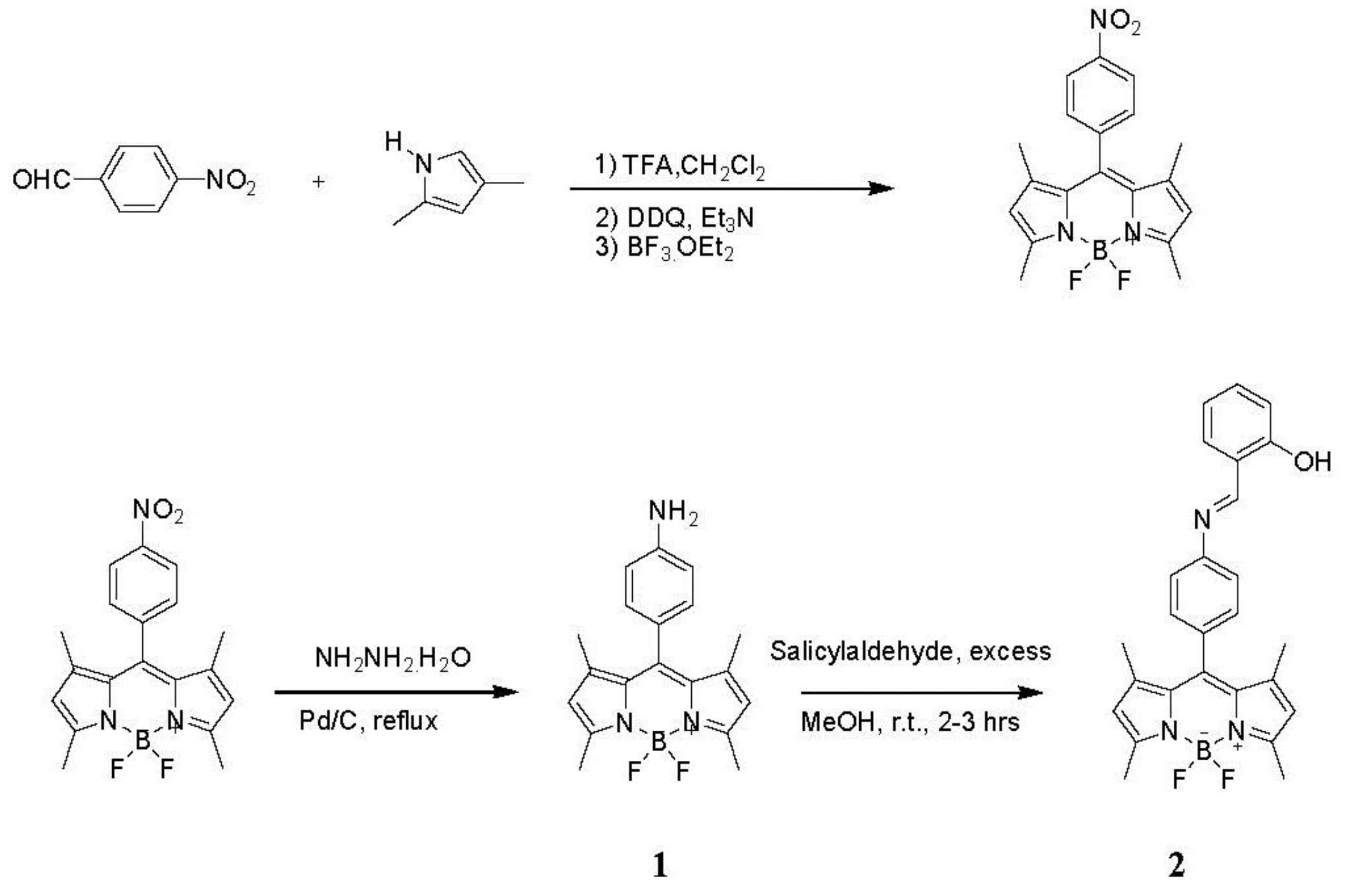

2.4. Synthesis of Aromatic Boron Dipyrromethenes (BDP) Derivatives

2.5. Absorption and Fluorescence Analysis

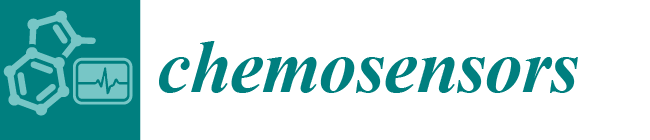

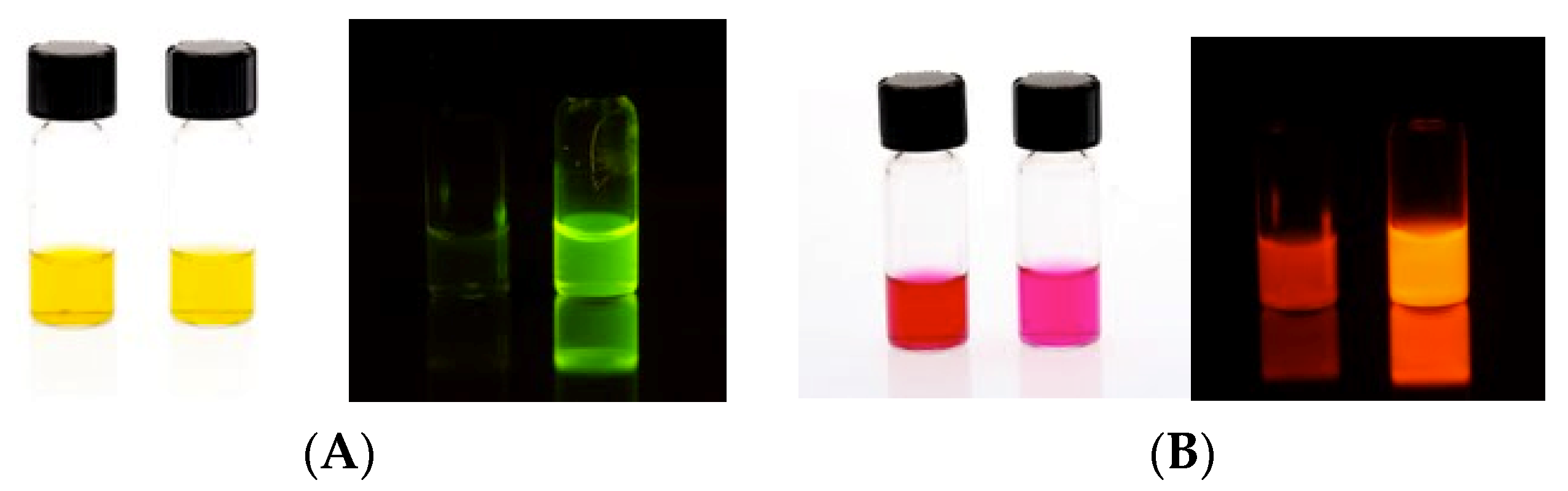

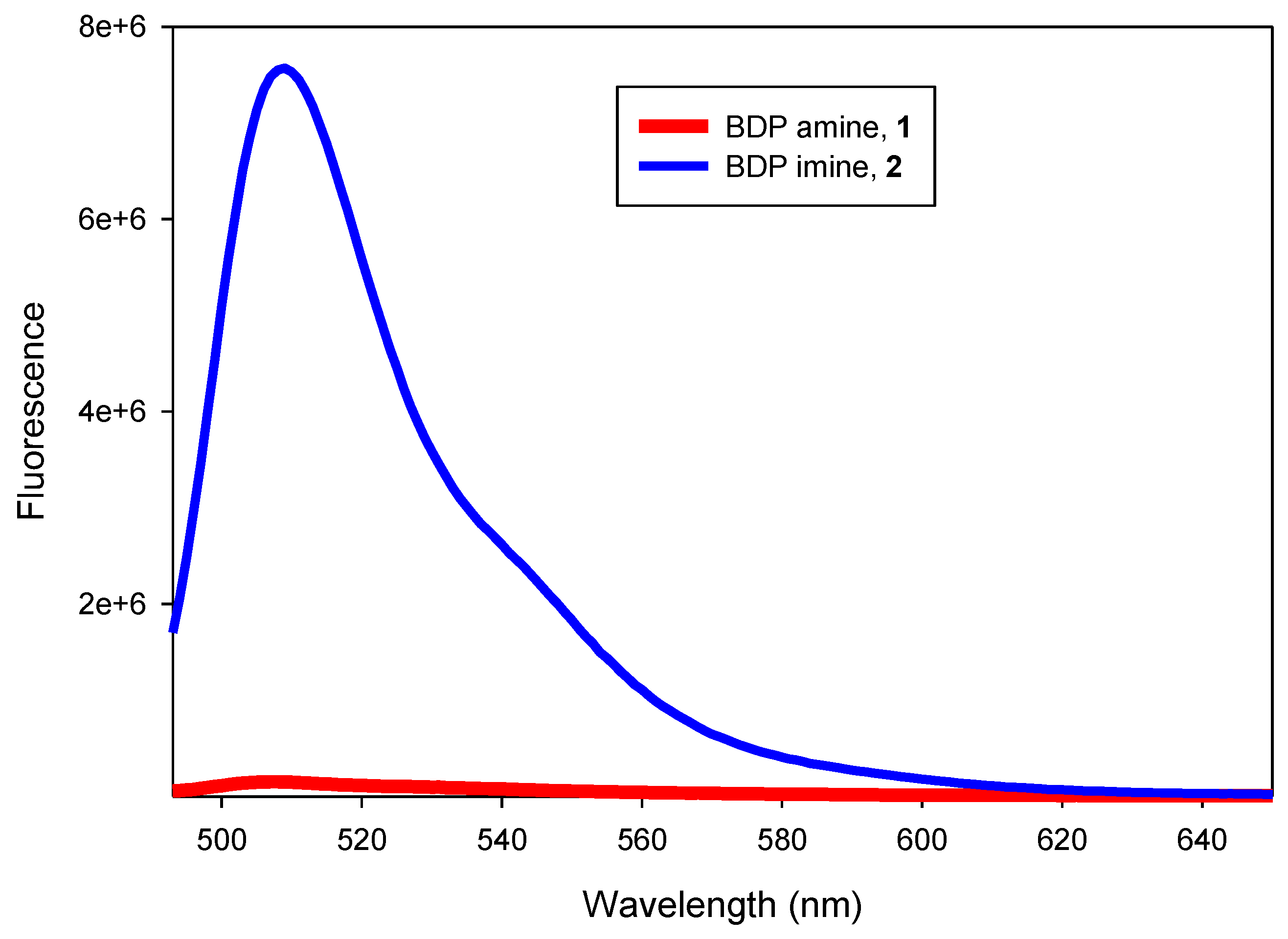

3. Results and Discussion

Synthesis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leikauf, G.D. Section 9. In Environmental Toxicants: Human Exposures and Their Health Effects, 3rd ed.; Lippmann, M., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 257–316. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, M.; Buldt, A.; Karst, U. Hydrazine reagents as derivatizing agents in environmental analysis—A critical review. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 2000, 366, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satcher, D. Toxicological Profile for Hydrazines; Agecy for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Musto, J.C.; Suslick, S.K. A Simple and Highly Sensitive Colorimetric Detection Method for Gaseous Formaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4046–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Dzyadevych, S.V. Conductometric Microbiosensors for Environmental Monitoring. Sensors 2008, 8, 2569–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferus, M.; Cihelka, J.; Civis, S. Formaldehyde in the environment—Determination of formaldehyde by laser and photoacoustic detection. Chem. Listy 2008, 102, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, R.; Kim, K.H. Experimental choices for the determination of carbonyl compounds in air. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 2708–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, G.J. New chromogenic and fluorogenic reagents and sensors for neutral and ionic analytes based on covalent bond formation–a review of recent developments. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toda, K.; Yoshioka, K.I.; Mori, K.; Hirata, S. Portable system for near-real time measurement of gaseous formaldehyde by means of parallel scrubber stopped-flow absorptiometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 531, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Kerman, K.; Fujihara, M.; Nagatani, N.; Hashiba, T.; Tamiya, E. Development of a novel hand-held formaldehyde gas sensor for the rapid detection of sick building syndrome. Sens. Actuators B 2005, 105, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.T.; Kerr, W.J.; Nordon, A.; Reglinski, J.; Robertson, C.; Turnbull, L.; Watt, C.M.; Cheung, A.; Johnstone, W. On –site determination of formaldehyde: A low cost measurement device for museum environments. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 623, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruo, Y.Y.; Nakamura, J.; Uchiyama, M. Development of formaldehyde sensing element using porous glass impregnated with beta-diketone. Talanta 2008, 74, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nakano, N.; Suzuki, K. Portable Sick House Syndrome Gas Monitoring System Based on Novel Colorimetric Reagents for the Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of Formaldehyde. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5695–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, G.J.; Spichiger, U.E.; Jona, W.; Langhals, H. Using N-Aminoperylene-3,4:9,10-tetracarboxylbisimide as a Fluorogenic Reactand in the Optical Sensing of Aqueous Propionaldehyde. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Miura, T.; Umezawa, N.; Urano, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Nagano, T. Rational design of fluorescein-based fluorescence probes, mechanism-based design of a maximum fluorescence probe for singlet oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 2530–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, Y. Sensitive and selective tumor imaging with novel and highly activatable fluorescence probes. Anal. Sci. 2008, 24, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunahara, H.; Urano, Y.; Kojima, H.; Nagano, T. Design and synthesis of a library of BODIPY-based environmental polarity sensors utilizing photoinduced electron-transfer-controlled fluorescence ON/OFF switching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5597–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loudet, A.; Burgess, K. BODIPY dyes and their derivatives: Syntheses and spectroscopic properties. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4891–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabe, Y.; Urano, Y.; Kikuchi, K.; Kojima, H.; Nagano, T. Highly sensitive fluorescence probes for nitric oxide based on boron dipyrromethene chromophore-rational design of potentially useful bioimaging fluorescence probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 126, 3357–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imahori, H.; Norieda, H.; Yamada, H.; Nishimura, Y.; Yamazaki, I.; Sakata, Y.; Fukuzumi, S. Light-harvesting and photocurrent generation by cold electrodes modified with mixed self-assembled monolayers of boron-dipyrrin and ferrocene-porphyrin-fullerene triad. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clunas, S.; Strory, J.M.D.; Rickard, J.E.; Horsley, D.; Harrington, C.R.; Wischik, C.M. 3,6-disubstituted xanthylium salts. Patent WO2010/067078, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Compound | Solvent | λexmax (nm) | λemmax (nm) | ФF b (at 23 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dioxane | 491 | 507 | 0.15 |

| 1 | Methanol | 488 | 503 | 0.002 |

| 2 | Dioxane | 492 | 509 | 0.5 |

| 2 | Methanol | 488 | 507 | 0.27 |

| Compound | Solvent | λexmax (nm) | λemmax (nm) | ФF b (at 23 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Methanol | 548 | 576 | 0.006 |

| 4 | Methanol | 548 | 578 | 0.06 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dilek, O.; Bane, S.L. Turn on Fluorescent Probes for Selective Targeting of Aldehydes. Chemosensors 2016, 4, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors4010005

Dilek O, Bane SL. Turn on Fluorescent Probes for Selective Targeting of Aldehydes. Chemosensors. 2016; 4(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors4010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleDilek, Ozlem, and Susan L. Bane. 2016. "Turn on Fluorescent Probes for Selective Targeting of Aldehydes" Chemosensors 4, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors4010005