Neurocognitive, Autonomic, and Mood Effects of Adderall: A Pilot Study of Healthy College Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

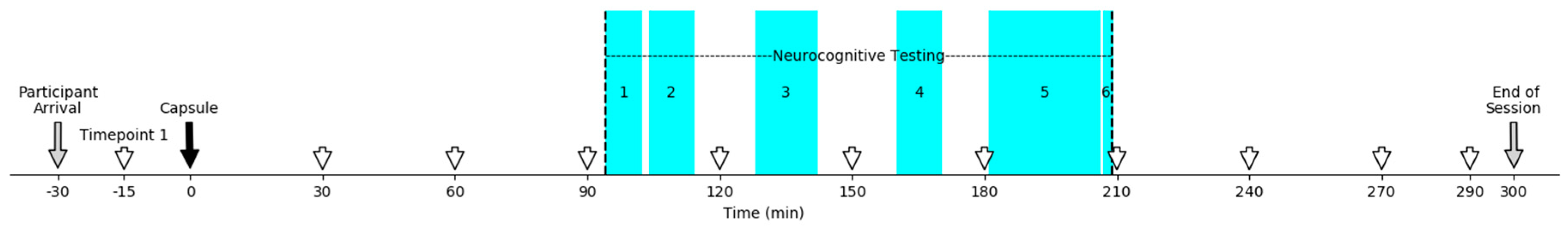

Study Design

3. Procedure

4. Instruments

Neurocognitive Measures

5. Activational Measures

6. Data Analyses

7. Statistical Power

8. Results

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

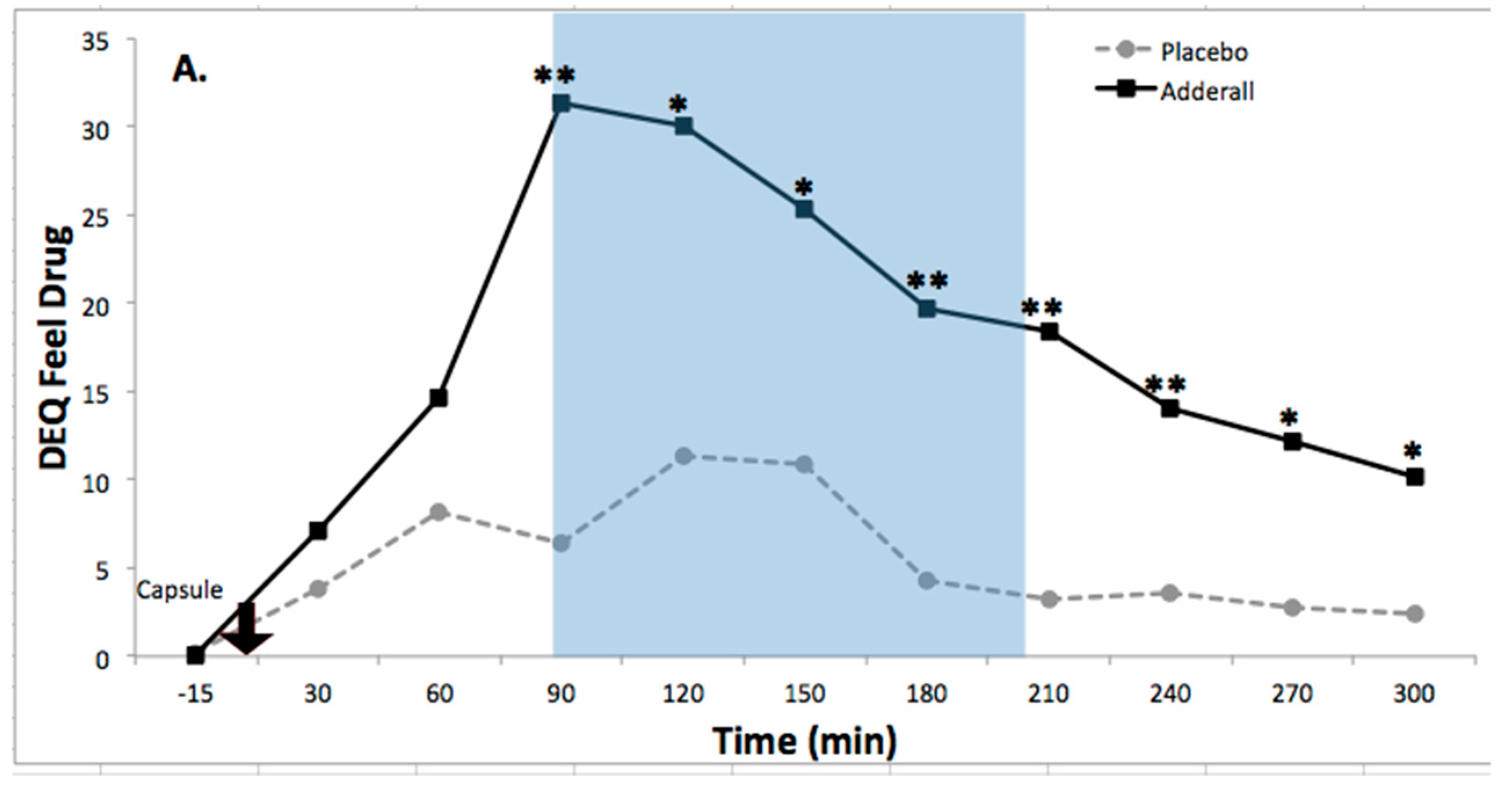

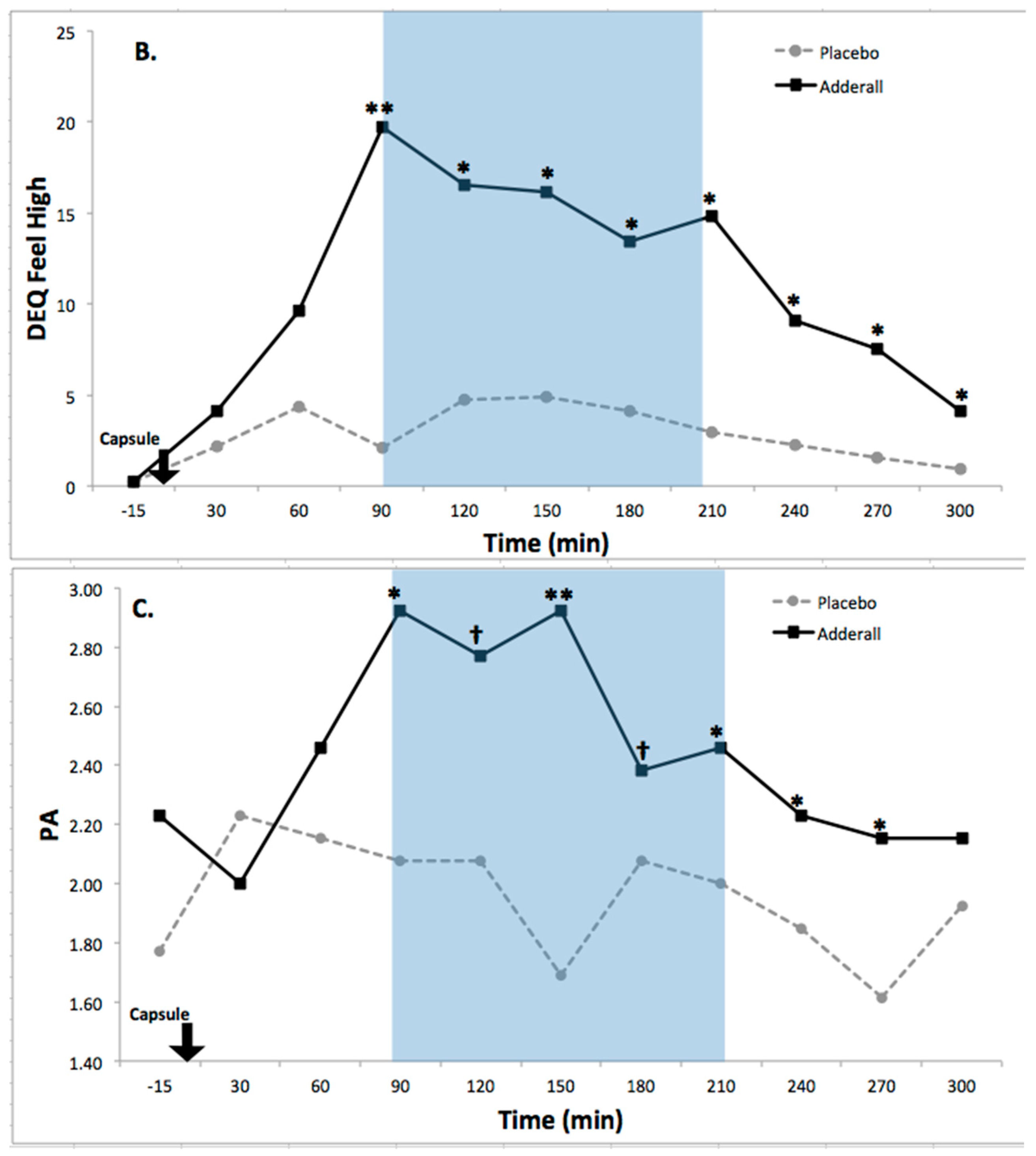

8.2. Drug Effects on Activation

8.3. Drug Effects on Neurocognitive Functioning

9. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, J.; Eagan, K.; Palucki Blake, L.; Hurtado, S.; Berdan, J.; Case, M. The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2012; Higher Education Research Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, L.E. College students with ADHD and other hidden disabilities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 931, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canu, W.H.; Carlson, G.L. Differences in heterosocial behavior and outcomes of ADHD-symptomatic subtypes in a college sample. J. Atten. Disord. 2003, 6, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Weyandt, L.L.; O’Dell, S.M.; Varejao, M. College students with ADHD: Current status and future directions. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormley, M.J.; Pinho, T.; Pollack, B.; Puzino, K.; Franklin, M.K.; Busch, C.; DuPaul, G.J.; Weyandt, L.L.; Anastopoulos, A.D. Impact of study skills and parent education on first-year GPA among college students with and without ADHD: A moderated mediation model. J. Atten. Disord. 2018, 22, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiligenstein, E.; Guenther, G.; Levy, A.; Savino, F.; Fulwiler, J. Psychological and academic functioning in college students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Coll. Health 1999, 47, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, T.L.; Rosén, L.A.; Ramirez, C.A. Psychological functioning differences among college students with confirmed ADHD, ADHD by self-report only, and without ADHD. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1999, 40, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Oster, D.R.; Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; DuPaul, G.J.; Anastopoulos, A.D. Neuropsychological functioning in college students with and without ADHD. Neuropsychology 2016, 31, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storebø, O.J.; Ramstad, E.; Krogh, H.B.; Nilausen, T.D.; Skoog, M.; Holmskov, M.; Rosendal, S.; Groth, C.; Magnusson, F.L.; Moreira-Maia, C.R.; et al. Methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Cochrane systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2015, 351, h5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fageera, W.; Traicu, A.; Sengupta, S.M.; Fortier, M.; Choudhry, Z.; Labbe, A.; Grizenko, N.; Joober, R. Placebo responses and its determinants in children with ADHD across multiple observers and settings: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneeton, N.; Maneeton, B.; Suttajit, S.; Reungyos, J.; Srisurapanont, M.; Martin, S.D. Exploratory meta-analysis on lisdexamfetamine versus placebo in adult ADHD. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Marraccini, M.E.; Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; Zavras, B.M.; Turcotte, K.D.; Munro, B.A.; Amoroso, A.J. Misuse of prescription stimulants among college students: A review of the literature and implications for 66 morphological and cognitive effects on brain functioning. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 21, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Weyandt, L.L.; Rossi, J.S.; Vilardo, B.A.; O’Dell, S.M.; Carson, K.M.; Verdi, G.; Swentosky, A. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of the efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in college students with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2012, 16, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, K.; Flory, K.; Humphreys, K.L.; Lee, S.S. Misuse of stimulant medication among college students: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babcock, Q.; Byrne, T. Student perceptions of methylphenidate abuse at a public liberal arts college. J. Am. Coll. Health 2000, 49, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.E.; Knight, J.R.; Teter, C.J.; Wechsler, H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction 2005, 100, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupont, R.L.; Coleman, J.J.; Bucher, R.H.; Wilford, B.B. NCharacteristics and motives of college students who engage in nonmedical use of methylphenidate. Am. J. Addict. 2008, 17, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Janusis, G.; Wilson, K.G.; Verdi, G.; Paquin, G.; Lopes, J.; Varejao, M.; Dussault, C. Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among a sample of college students: Relationship with psychological variables. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judson, R.; Langdon, S.W. Illicit use of prescription stimulants among college students: Prescription status, motives, theory of planned behaviour, knowledge and self-diagnostic tendencies. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossaer, J.B.; Gray, J.A.; Miller, S.E.; Enck, G.; Gaddipati, V.C.; Enck, R.E. The use and misuse of prescription stimulants as “cognitive enhancers” by students at one academic health sciences center. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, B.A.; Weyandt, L.L.; Marraccini, M.E.; Oster, D.R. The relationship between nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, executive functioning, and academic outcomes. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mache, S.; Eickenhorst, P.; Vitzthum, K.; Klapp, B.F.; Groneberg, D.A. Cognitive-enhancing substance use at German universities: Frequency, reasons and gender differences. Wiener Med. Wochenschr. 2012, 162, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; Weyandt, L.L.; Ernudottir, G.B. Prescription stimulant misuse and ADHD symptomatology among college students in Iceland. J. Atten. Disord. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, L.J.; Liechti, M.E.; Herzig, F.; Schaub, M.P. To dope or not to dope: Neuroenhancement with prescription drugs and drugs of abuse among Swiss university students. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, I.; Bard, I.; Jackson, J. Robust resilience and substantial interest: A survey of pharmacological cognitive enhancement among university students in the UK and Ireland. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; Weyandt, L.L.; Munro, B.A. Prescription stimulant misuse: International findings and implications for policy, prevention, and intervention. ADHD Rep. 2016, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arria, A.M.; O’Grady, K.E.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; Wish, E.D. Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants and analgesics: Associations with social and academic behaviors among college students. J. Drug Issues 2008, 38, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilieva, I.; Boland, J.; Farah, M.J. Objective and subjective cognitive enhancing effects of mixed amphetamine salts in healthy people. Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.E.; Farah, M.J. Are prescription stimulants “smart pills”? Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.L.; Lejuez, C.W.; de Wit, H. Personality and gender differences in effects of D-amphetamine on risk-taking. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 15, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marraccini, M.E.; Weyandt, L.L.; Rossi, J.S.; Gudmundsdottir, B.G. Neurocognitive enhancement or impairment? A systematic meta-analysis of prescription stimulant effects on processing speed, decision-making, planning, and cognitive perseveration. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 24, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repantis, D.; Schlattmann, P.; Laisney, O.; Heuser, I. Modafinil and methylphenidate for neuroenhancement in healthy individuals: A systematic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morean, M.E.; de Wit, H.; King, A.; Sofuoglu, M.; Rueger, S.Y.; O’Malley, S. The Drug Effects Questionnaire: Psychometric support across multiple substances. Psychopharmacology 2013, 227, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrone, J.V.; Depue, R.A.; Scherer, A.J.; White, T.L. Film-induced incentive motivation and positive activation in relation to agentic and affiliative components of extraversion. Pers. Ind. Differ. 2000, 29, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.L.; Lott, D.; de Wit, H. Personality and the subjective effects of acute amphetamine in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depue, R.A.; Fu, Y. On the nature of extraversion: Variation in conditioned contextual activation of dopamine-facilitated affective, cognitive, and motor processes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.L.; Monnig, M.; Walsh, E.; Nitenson, A.Z.; Harris, A.D.; Cohen, R.A.; Porges, E.C.; Woods, A.J.; Lamb, D.G.; Boyd, C.A.; et al. Psychostimulant Drug Effects on Glutamate, Glx, and Creatine in the Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Subjective Response in Healthy Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59 (Suppl. 20), 22–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Oster, D.R.; Marraccini, M.E.; Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; Munro, B.A.; Zavras, B.M.; Kuhar, B. Pharmacological interventions for adolescents and adults with ADHD: Stimulant and nonstimulant medications and misuse of prescription stimulants. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2014, 7, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th ed.; Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R.W.; McGrew, K.S.; Mather, N. Woodcock-Johnson III; Riverside Publishing: Itasca, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Multi-Health Systems Inc. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test, 3rd ed.; MHS: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K.; Guy, S.C.; Kenworthy, L. The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt, J.L.; Bryant, B.R. Gray Oral Reading Test, 3rd ed.; Pro-Ed: Austin, TX, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.L.; Justice, A.J.H.; de Wit, H. Differential subjective effects of D-amphetamine by gender, hormone levels and menstrual cycle phase. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002, 73, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.L. Beyond sensation seeking: A conceptual framework for individual differences in psychostimulant drug effects in healthy humans. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 13, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depue, R.A. Interpersonal behavior and the structure of personality: Neurobehavioral foundation of agentic extraversion and affiliation. In Biology of Personality and Individual Differences; Turhan, C., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 60–92. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.L.; Grover, V.K.; de Wit, H. Cortisol effects of D-amphetamine relate to traits of fearlessness and aggression but not anxiety in healthy humans. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 85, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawk, L.W.; Fosco, W.D.; Colder, C.R.; Waxmonsky, J.G.; Pelham, W.E.; Rosch, K.S. How do stimulant treatments for ADHD work? Evidence for mediation by improved cognition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pievsky, M.A.; McGrath, R.E. Neurocognitive effects of methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 90, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, R.M.; Lance, C.E.; Isquith, P.K.; Fischer, A.S.; Giancola, P.R. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Adult version in healthy adults and application to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2013, 28, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, E.; Bershad, A.K.; de Wit, H. Effects of D-amphetamine upon psychosocial stress responses. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropsey, K.L.; Schiavon, S.; Hendricks, P.S.; Froelich, M.; Lentowicz, I.; Fargason, R. Mixed-amphetamine salts expectancies among college students: Is stimulant induced cognitive enhancement a placebo effect? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 178, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, A.M.; Scott, E. Maximizing power in randomized designs when N is small. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

| Task | Placebo M (SD) | Adderall M (SD) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRIEF-A—BRI † | 38.23 (7.47) | 39.92 (7.10) | 0.23 |

| BRIEF-A—GEC † | 96.15 (20.10) | 98.92 (19.72) | 0.14 |

| BRIEF-A—MI | 57.92 (13.58) | 59.00 (13.83) | 0.08 |

| CPT 3—Omission Errors | 46.82 (5.23) | 46.00 (4.17) | −0.17 |

| CPT 3—Commission Errors † | 53.82 (11.79) | 50.64 (9.23) | −0.30 |

| CPT 3—Hit Reaction Time † | 49.36 (8.96) | 47.46 (5.75) | −0.25 |

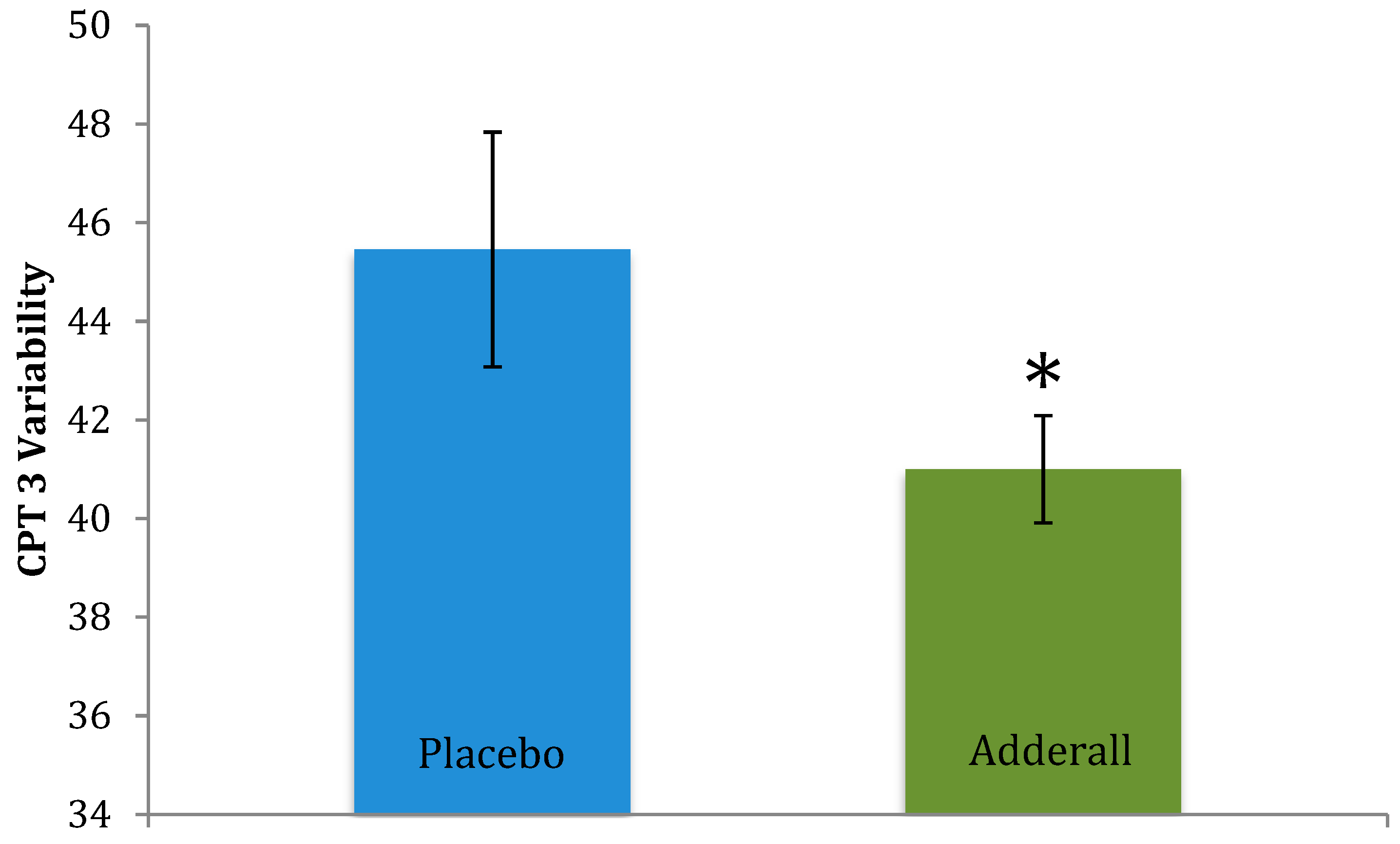

| CPT 3—Variability * | 45.46 (7.88) | 41.00 (3.61) | −0.73 |

| DS Total | 34.00 (4.78) | 33.46 (6.32) | −0.10 |

| DS Forward * | 12.62 (1.45) | 11.69 (2.39) | −0.47 |

| DS Backward | 10.62 (2.63) | 10.46 (2.57) | −0.06 |

| GORT—ORI | 98.77 (8.61) | 99.69 (8.61) | 0.11 |

| PDE-SR | 44.39 (9.55) | 47.54 (20.33) | 0.20 |

| WJ | 43.62 (4.86) | 44.54 (5.87) | 0.17 |

| Measure | Drug F(1,12) | Time F(10,120) | Drug × Time F(10,120) | Partial Eta-Squared Effect Size | Cohen’s d Effect Size | Direction of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | 12.84 *** | 3.52 **** | 4.30 ***** | 0.52 | 1.25 | Increased |

| Systolic BP | 10.1 ** | 1.77 | 3.36 **** | 0.46 | 1.05 | Increased |

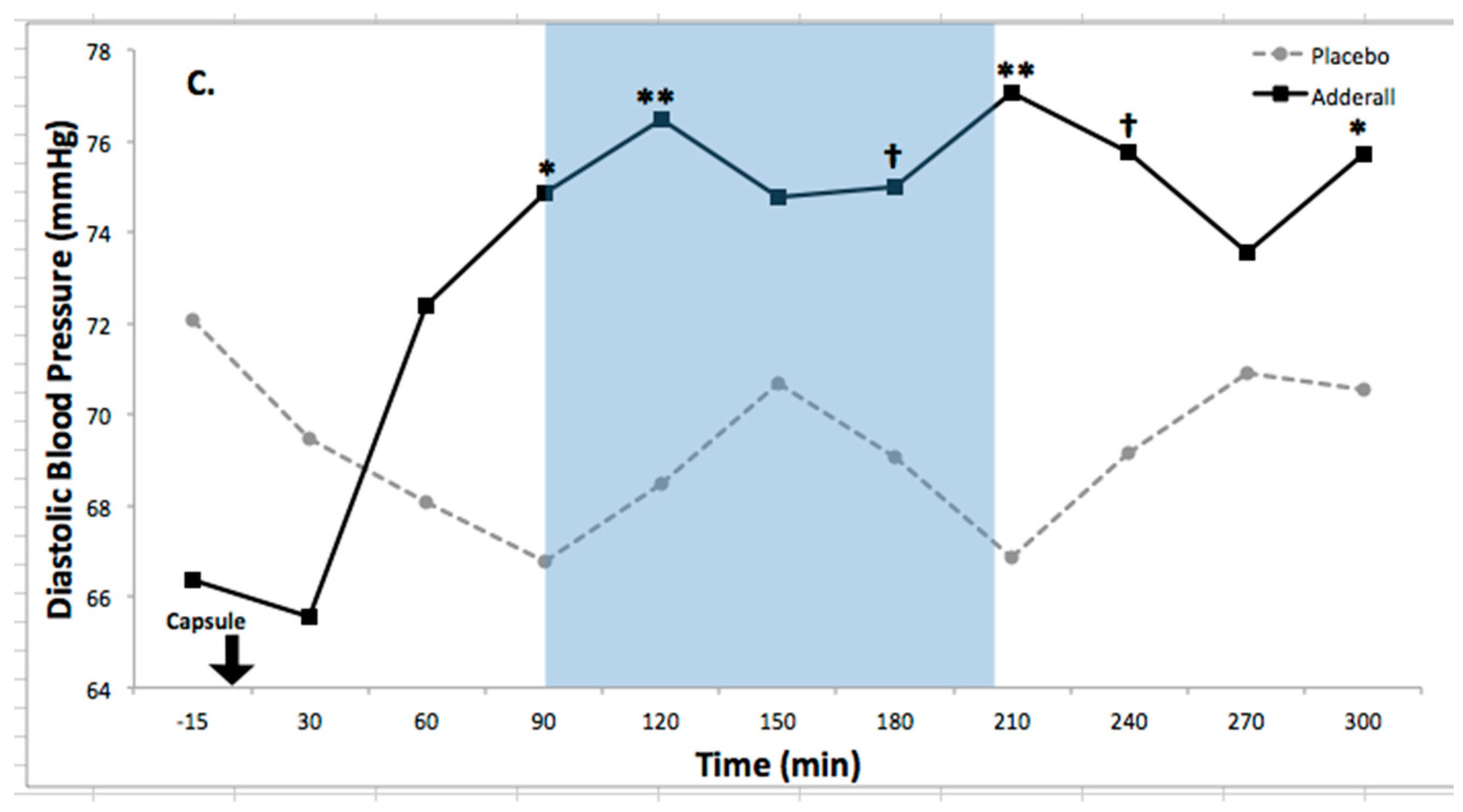

| Diastolic BP | 5.38 * | 1.12 | 3.28 **** | 0.31 | 0.86 | Increased |

| Feel Drug Effect | 9.64 ** | 6.87 ***** | 2.82 *** | 0.45 | 1.26 | Increased |

| Feel High | 7.06 * | 3.35 **** | 2.46 ** | 0.37 | 1.04 | Increased |

| PA | 5.27 * | 1.18 | 2.20 * | 0.31 | 0.71 | Increased |

| Task | Placebo M (SD) | Adderall M (SD) | t-test | p | Direction of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digit Span Forward * | 12.62 (1.45) | 11.69 (2.39) | −1.80 | 0.048 | Worsened |

| CPT 3—Variability * | 45.46 (7.88) | 41.00 (3.61) | −2.25 | 0.024 | Improved |

| CPT 3—Commission Errors † | 53.82 (11.79) | 50.64 (9.23) | −1.74 | 0.056 | Improved |

| CPT 3—Hit Reaction Time † | 49.36 (8.96) | 47.46 (5.75) | −1.47 | 0.086 | Improved |

| BRIEF-A—BRI † | 38.23 (7.47) | 39.92 (7.10) | 1.54 | 0.075 | More negative perceptions |

| BRIEF-A—GEC † | 96.15 (20.10) | 98.92 (19.72) | 1.35 | 0.10 | More negative perceptions |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weyandt, L.L.; White, T.L.; Gudmundsdottir, B.G.; Nitenson, A.Z.; Rathkey, E.S.; De Leon, K.A.; Bjorn, S.A. Neurocognitive, Autonomic, and Mood Effects of Adderall: A Pilot Study of Healthy College Students. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030058

Weyandt LL, White TL, Gudmundsdottir BG, Nitenson AZ, Rathkey ES, De Leon KA, Bjorn SA. Neurocognitive, Autonomic, and Mood Effects of Adderall: A Pilot Study of Healthy College Students. Pharmacy. 2018; 6(3):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030058

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeyandt, Lisa L., Tara L. White, Bergljot Gyda Gudmundsdottir, Adam Z. Nitenson, Emma S. Rathkey, Kelvin A. De Leon, and Stephanie A. Bjorn. 2018. "Neurocognitive, Autonomic, and Mood Effects of Adderall: A Pilot Study of Healthy College Students" Pharmacy 6, no. 3: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030058

APA StyleWeyandt, L. L., White, T. L., Gudmundsdottir, B. G., Nitenson, A. Z., Rathkey, E. S., De Leon, K. A., & Bjorn, S. A. (2018). Neurocognitive, Autonomic, and Mood Effects of Adderall: A Pilot Study of Healthy College Students. Pharmacy, 6(3), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030058