Creative Arts Therapies as Temporary Home for Refugees: Insights from Literature and Practice

Abstract

:“Home is where I can grow” (“Heimat ist, wo ich wachsen kann”)Title of a theatre play by female refugees from Iran

1. Home and Homesickness for Refugees

2. Aesthetics: Arts as Both Sensual and Transcendental

3. Creative Arts Therapies and Refugees: Aesthetic Experience Can Be a Shelter

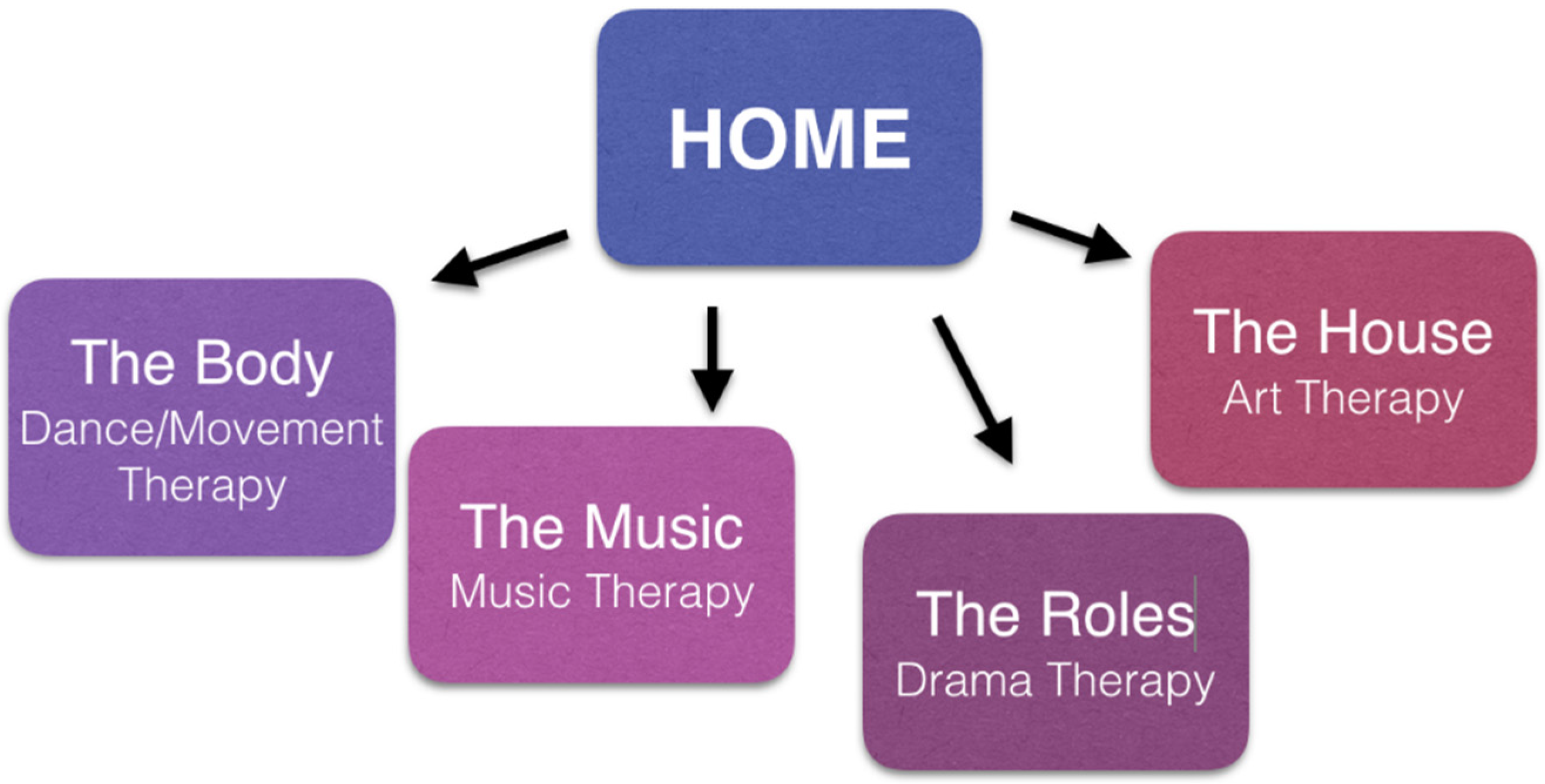

4. The Creative Arts Therapies as a Temporary Home

4.1. Dance/Movement Therapy

4.2. Drama Therapy

4.3. Music Therapy

4.4. Art Therapy

4.5. The Container and the Bridge

5. Clinical and Research Examples

5.1. State of Limbo

5.2. Creative Arts Therapies as Container

5.3. Creative Arts Therapies as Bridge

5.4. Homesickness: Selected Results

6. Obstacles to the Process of Successful Transitioning

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallett, S. Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 52, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Home and Away: Narratives of Migration and Estrangement. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 1999, 2, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A. In Search of Home. J. Appl. Philos. 1994, 11, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.C. Die psychosoziale Situation Asylsuchender am Beispiel der Stadt Heidelberg zur Zeit der Deutsch-Deutschen Wende; Ibidem: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K. Homes and Homelessness. In Home Environments; Altman, I., Werner, C., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, R. (Ed.) Therapeutic Care for Refugees: No Place Like Home; Karnac Book: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frigessi-Castelnuovo, D.; Risso, M. Emigration und Nostalgia; Cooperative Books: Frankfurt, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg, M.A.; Vingerhoets, A.J. Psychological Aspects of Geographical Moves; Amsterdam Academic Archive; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, M.; Welch, M. An analysis of the concept of homesickness. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1992, 6, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, M.A.; Vingerhoets, A.J.; Van Heck, G.L. Homesickness: A review of the literature. Psychol. Med. 1996, 26, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H. Refugees, the State and the Concept of Home. Refug. Surv. Q. 2013, 32, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, K. In limbo: Movement psychotherapy with refugees and asylum seekers. In Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants: Reaching across Borders; Dokter, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.A. The paradox of expressing speechless terror: Ritual liminality in the creative arts therapies’ treatment of posttraumatic distress. Arts Psychother. 2009, 36, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, G.; Gerber, N.; Scotti, V. Towards an aesthetic intersubjective paradigm for arts-based research: An art therapy perspective. UNESCO Obs. J. Multi-Discipl. Res. Arts 2015, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, P. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. The origin of the work of art. In Philosophies of Art & Beauty: Selected Readings in Aesthetics from Plato to Heidegger; Hofstadter, A., Kuhns, R., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 3–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.G. Truth and Method, 2nd ed.; Weinsheimer, J.; Marshall, D.G., Translators; The Continuum International Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee of Arts Therapies Professions. Artists and Art Therapists; Carnegie UK Trust: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dokter, D. (Ed.) Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants: Reaching across Borders; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, S.C.; Weidinger-von der Recke, B. Traumatised refugees: An integrated dance and verbal therapy approach. Arts Psychother. 2009, 36, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.C. Arts and health: Active factors and a theory framework of embodied aesthetics. Arts Psychother. 2017, 54, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, K. The Embodied Self; Karnac Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, S.C.; Fuchs, T. Embodied arts therapies. Arts Psychother. 2011, 38, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeks, L. Understanding the Personal Meaning of the Metaphor “Body as Home” for Application in Dance/Movement Therapy. Master’s Thesis, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, A. Bodystories: A Guide to Experiential Anatomy; University Press of New England: Lebanon, NH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haen, C. Vanquishing Monsters. In Creative Interventions with Traumatized Children; Malchiodi, C.A., Ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, C.; Beauregard, C.; Daignault, K.; Petrakos, H.; Thombs, B.D.; Steele, R.; Hechtman, L. A cluster randomized-controlled trial of a classroom-based drama workshop program to improve mental health outcomes among immigrant and refugee youth in special classes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkibi, H.; School of Creative Arts Therapies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. Personal Communication, 28 June 2017.

- Scott-Danter, H. Between theatre and therapy: Experiences of a drama therapist in Mozambique. In Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants: Reaching across Boriders; Dokter, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, H. Drama therapy with newly-arrived refugee women. In Trauma Informed Drama Therapy: Transforming Clinics, Classrooms, and Communities; Sajnani, N., Ed.; Charles C Thomas Publisher: Springfield, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, W. The Therapeutic Edge; Sears, M., Ed.; Barcelona Publishers: Gilsum, NH, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch, S. Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunt, L.; Stige, B. Music Therapy: An Art beyond Words; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bruscia, K.E. Defining Music Therapy, 3rd ed.; Barcelona: University Park, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ansdell, G.; Pavlicevic, M. Community Music Therapy; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, N. Sounds in the world: Multicultural influences in music therapy in clinical practice and training. Music Ther. Perspect. 2005, 23, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharinova-Sanderson, O. Promoting integration and socio-cultural change: Community music therapy with traumatized refugees in Berlin. In Community Music Therapy; Pavlicevic, M., Ansdell, G., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2004; pp. 358–387. [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel, S. Möglichkeiten von Musiktherapie in der psychosozialen Versorgung von Flüchtlingen in Deutschland. Eine qualitative Befragung. Master’s Thesis, SRH Hochschule Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 2016, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- American Art Therapy Association. 2017. Available online: https://arttherapy.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2017).

- Malchiodi, C.A. (Ed.) Handbook of Art Therapy; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, J.A. (Ed.) Approaches to Art Therapy: Theory and Technique; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Calisch, A. Multicultural training in art therapy: Past, present, and future. Art Ther. 2003, 20, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim-Cahen, T. Art therapy with asylum seekers: Humanitarian relief. In Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants: Reaching across Borders; Dokter, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, F. A search for home: The role of art therapy in understanding the experiences of Bosnian refugees in Western Australia. Art Ther. 2002, 19, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, P. Unterstützungsangebote für Migranten mit Fluchterfahrungen—Eine Bedarfserhebung für Ein Musiktherapeutisches Konzeptdesign. Bachelor’s Thesis, SRH Hochschule Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 2017, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Heriniaina, N.; Schröder, M.; Joksimovic, L. Kunsttherapie mit Flüchtlingen. Ärztliche Psychotherapie und Psychosomatische Medizin 2013, 8, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sajnani, N.; Nadeau, D. Creating safer spaces for immigrant women of color: Performing the politics of possibility. Can. Woman Stud. 2006, 25, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.; Melzak, S. Using storytelling in psychotherapeutic group work with young refugees. Group Anal. 2005, 38, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruud, E. Music Therapy: Improvisation, Communication and Culture; Barcelona Publishers: Gilsum, NH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ansdell, G. Community music therapy & the winds of change. Voices 2002, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Art as Experience; Capricorn: New York, NY, USA, 1958; Original work published 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam, A. Dance movement therapy with south Asian woman in Britain. In Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants Reaching across Borders; Dokter, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.A. Dance/movement therapy approaches to fostering resilience and recovery among African adolescent torture survivors. Torture 2007, 17, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, C.; Guzder, J. School-based prevention programs for refugee children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 17, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Baker, F.; Day, T. From healing rituals to music therapy: Bridging the cultural divide between therapist and young Sudanese refugees. Arts Psychother. 2004, 31, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amir, D. The use of Israeli folksongs in dealing with women’s bereavement and loss in music therapy. In Arts Therapists, Refugees and Migrants Reaching across Borders; Dokter, D., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Valle, E. Art therapy as a tool in the acculturation of the immigrant mental patient. Pratt Inst. Creat. Arts Ther. Rev. 1981, 2, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, T.H.; Rahe, R.H. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1967, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdascheck, C. Asylsuchende–Migration–Phänomenologie. Musik-, Tanz- und Kunsttherapie 2016, 25, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, S.; Tošić, J. Refugees as a particular form of transnational migrations and social transformations: Socioanthropological and gender aspects. Curr. Sociol. 2005, 53, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, V.C.; Sveaass, N.; Morken, G. The role of trauma and psychological distress on motivation for foreign language acquisition among refugees. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2014, 7, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilesnik, B.; Koch, S.C.; Stompe, T. Psychische Gesundheit von Migranten. Ihre Abhängigkeit von Akkulturation und Religiosität bei jüdischen Immigranten aus der ehemaligen Sowjetunion in Österreich [Psychological health of migrants. Its reliance on acculturation strategy and religiosity in Jewish immigrants from former Soviet Union in Austria]. Neuropsychiatrie 2017. under review. [Google Scholar]

| Life Events before Arrival in Germany | # of Persons Affected |

|---|---|

| Torture | 3 persons |

| Starvation | 5 persons |

| Danger of Own Death | 7 persons |

| Loss of Work | 9 persons |

| Imprisonment | 10 persons |

| Death of Close Relatives | 10 persons |

| Social Decline | 11 persons |

| Discrimination | 13 persons |

| War | 13 persons |

| Death of Friends | 14 persons |

| Hiding and Illegality | 15 persons |

| Persecution of Friends and Relatives | 16 persons |

| Separation from Family and Friends | 17 persons |

| Stressors in Germany | # of Persons Affected |

|---|---|

| Loneliness | 2 persons |

| Language Difficulties | 3 persons |

| Hostility toward Strangers | 4 persons |

| Poor Living Conditions | 4 persons |

| Loss of Freedom to go anywhere one wants | 8 persons |

| Experiences of Persecution and Flight | 8 persons |

| Lack of Work | 9 persons |

| No Passport | 10 persons |

| Insecurity of Status (in Asylum Process) | 10 persons |

| Dependency on Social Welfare | 12 persons |

| Insecure Residential Status | 12 persons |

| Homesickness | 16 persons |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dieterich-Hartwell, R.; Koch, S.C. Creative Arts Therapies as Temporary Home for Refugees: Insights from Literature and Practice. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7040069

Dieterich-Hartwell R, Koch SC. Creative Arts Therapies as Temporary Home for Refugees: Insights from Literature and Practice. Behavioral Sciences. 2017; 7(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleDieterich-Hartwell, Rebekka, and Sabine C. Koch. 2017. "Creative Arts Therapies as Temporary Home for Refugees: Insights from Literature and Practice" Behavioral Sciences 7, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7040069