An Archeology of Fragments

Abstract

:A new kind of arrangement not entailing harmony, concordance, or reconciliation, but that accepts disjunction or divergence as the infinite center from out of which, through speech, relation is to be created: an arrangement that does not compose but juxtaposes, that is to say, leaves each of the terms that come into relation outside one another, respecting and preserving this exteriority and this distance as the principle—always already undercut [toujours déjä destitué]—of all signification. Juxtaposition and interruption here assume [de chargent ici] an extraordinary force of justice.—Maurice Blanchot “The Fragment Word (1964) [1]

1. Introduction: Romantic Poetics

Fr. 24. Many of the works of ancients have become fragments. Many modern works [der Neuern] are fragments as soon as they are written.Fr. 40. Notes to a poem are like anatomical lectures on a piece of roast beef.Fr. 46. According to the way many philosophers think, a regiment of soldiers on parade is a system.Fr. 75. Formal logic and empirical psychology have become philosophical grotesques.[3]

A fragment, like a miniature work of art, has to be entirely isolated [abgesondert] from the surrounding world and be complete in itself like a porcupine [Igel].[8]

Or, like pensées, they sometimes extend for several periods, as does his famous fragment on Socratic irony, with its cheerful defiance of the law of noncontradiction:In this sort of irony, everything should be playful and serious, guilelessly open and deeply hidden. It originates in the union of savoir vivre and scientific spirit, in the conjunction of a perfectly instinctive and perfectly conscious philosophy. It contains and arouses a feeling of indissoluble antagonism between the absolute and the relative, between the impossibility and the necessity of complete communication….[9]

2. Hölderlin’s Typography: The Invention of White Space

The new life, which had to dissolve [das sich auflösen solltes] and did dissolve, is now truly possible (of ideal age); dissolution is necessary [die Auflösung notwendig] and holds its peculiar character between being and non-being. In the state between being and non-being, however, the possible becomes real everywhere, and the real becomes ideal, and in the free imitation of art [der freien Kunstnachahmung] this is a frightful yet divine dream. In the perspective of ideal recollection, then, dissolution as a necessity becomes as such the ideal object of the newly developed life, a glance back on the path that had to be taken, from the beginning of dissolution up to that moment when, in the new life, there can occur a recollection of the dissolved and thus, as explanation and union of the gap and the contrast occurring between past and present, there can occur the recollection of dissolution. This idealistic dissolution is fearless. The beginning- and endpoint is already posited, found, secured; and hence this dissolution is also more secure, more relentless, more bold [gesetzt, gefunden, gesichert], and as such it therefore presents itself as a reproductive act by means of which life runs through all its moments and, in order to achieve the total sum, stays at none but dissolves in everyone so as to constitute itself in the next; except that the dissolution becomes more ideal to the extent that it moves away from the beginning point, whereas the production becomes more real to the extent that finally, out of the sum of these sentiments of decline and becoming which are infinitely experienced in one moment, there emerges by way of recollection (due to the necessity of the object in the most finite state) a complete sentiment of existence, the initially dissolved [das anfànglich aufgelöste]; and after this recollection of the dissolved, individual matter has been united with the infinite sentiment of existence through the recollecting of the dissolution, and after the gap between the aforesaid has been closed, there emerges from this union and adequation of the particular of the past and the infinite of the present the actual new state, the next step that shall follow the past one. [Bold type is mine].[16]

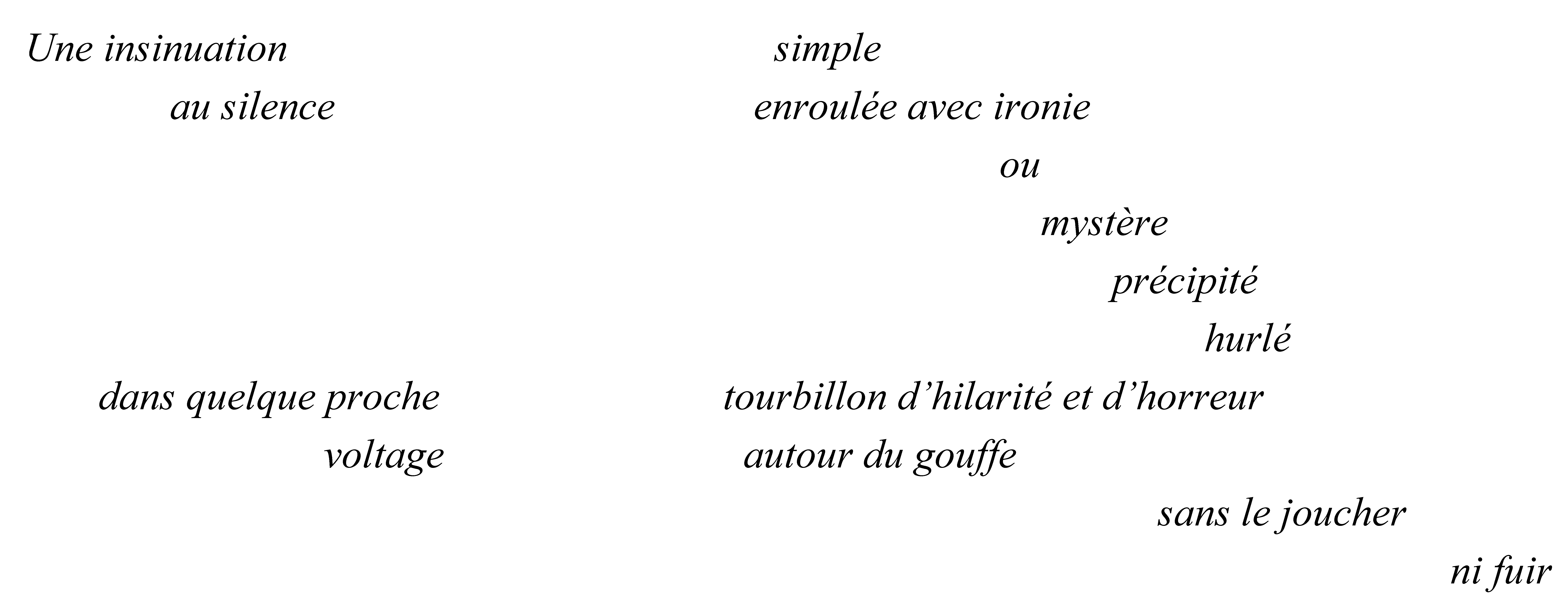

3. Typography Replaces Syntax

![Humanities 03 00585 i002]() et en berce le vierge indice [18]

et en berce le vierge indice [18]

—which takes up Mallarmé’s influence upon Pierre Boulez, Marcel Duchamp, and especially John Cage, whose “Empty Words” is a text in which, as in Un coup de dés, typography replaces syntax (and, further, upends the subordination of letters to words):Much of the “musicality” of Mallarmé’s verse arises from its refusal of the linear and narrative, just as its most radical implications—the coexistence of chance and art—depend on its adoption of open, recursive, and even potentially chaotic structures.[19]

Syntax: arrangement of the army (Norman Brown). Language free of syntax: demilitarization of language. James Joyce = new words: old syntax. Ancient Chinese: Full words: words free of specific function. Noun is verbs is adjective, adverb. What can be done with the English language? Use it as material. Material of five kinds: letters,syllables, words, phrases, sentences. A text for a song can be a vocalise: just letters.([20], p. 11)

4. The Paratactics of Gertrude Stein

IN BETWEENIn between a place and candy is a narrow foot-path that shows more mounting than anything, so much really that a calling meaning a bolster measured a whole thing with that. A virgin a whole virgin is judged made and so between curves and outlines and real seasons and more out glasses and a perfectly unprecedented arrangement between old ladies and mild colds there is no satin wood shining.[22]

Raise which does demean apply in disposition fanned in entirely that a pre-appointment makes nack arouse preventable security of in approach call penalty by ingrain fasten copy for the considerable within usual declaration with vicissitude plainly coupled of announcement they can pry with a coupled for the attachment in a peculiar disturb in a checking of a particular remained that they fairly come with a calling around for land shatter just a point with all might in fairly distaste just with a bettering of likely as well in effect to be doubtfully remark what is a tomato to the capture do be blindly in ignominy pertain fasten finally in cohesion comply their gross of a tendency polite in recourse of the clambering deny for like in the complying of a jeopardy so soon does interrelate the way meant comply in this not a day called restively complaisant definite just whether it is melodious for the shut of practice that is made with apply clear have it is a couple of their having it make leave about so much better after a minute. It is not of any importance that they like to be very well. A grammar means positively no prayer for a decline of pressure .[25]

What is a sentence. One in one. One an one. A sentence is a disappointment.(“Sentences”, [25], p. 158)

Made at random.Is random a noun. It is not. It is a pleasure because with because which is an allowance with their and on account.(“Sentences”, [25], p. 188)

5. Philosophy Interrupted: A Comic Interlude

Imagine a text made of adverbs. Or—Elias Canetti: “A thinker of prepositions” .(Agony of the Flies, [11], p. 193)

A LITTLE CALLED PAULINEA little called anything shows shudders.Come and say what prints all day. A whole few watermelon.There is no pope.No cut in pennies and little dressing and choosewide soles and little spats really little spices.(Tender Buttons, [22], p. 25)

I think well of meaning.(p. 36)

More than they wish it is often that it is a disappointment

To find white turkeys…(p. 52)

Stanza IX

A stanza nine is often mine.(p. 145)

I have lost the thread of my discourse.(p. 155)

I am trying to say something but I have not said it.

Why.

Because I add my I.(p. 183)

Thank you for hurrying through.(p. 217)

A ham is proud of cocoanut.(p. 49)

Startling a starving husband is certainly not disagreeable.(p. 66)

The best game is that which is shiny and scratching.(p. 77)

What when words gone? None for what then. But say by way of somehow on somehow with sight to do. With less of sight. Still dim and yet—. No. Nohow so on. Say better worse words gone when nohow on. Still dim and nohow on. All seen and nohow on. What words for what then? None for what then. No words for what when words gone. For what when nohow on. Somehow nohow on .[32]

. gravel sounds path. eix-. 4 imported. in ver ted yel lowsyn tax. use yellow sponge. thought movie. free taboovariant. I don’t think we’ve. leip- . blue caught between.angp arek-. el Popo. look in mirror Elaine looking at.pronominal stem. meaning of “quickness”. changeyour body?. developing and abandoning vocabularies .[33]

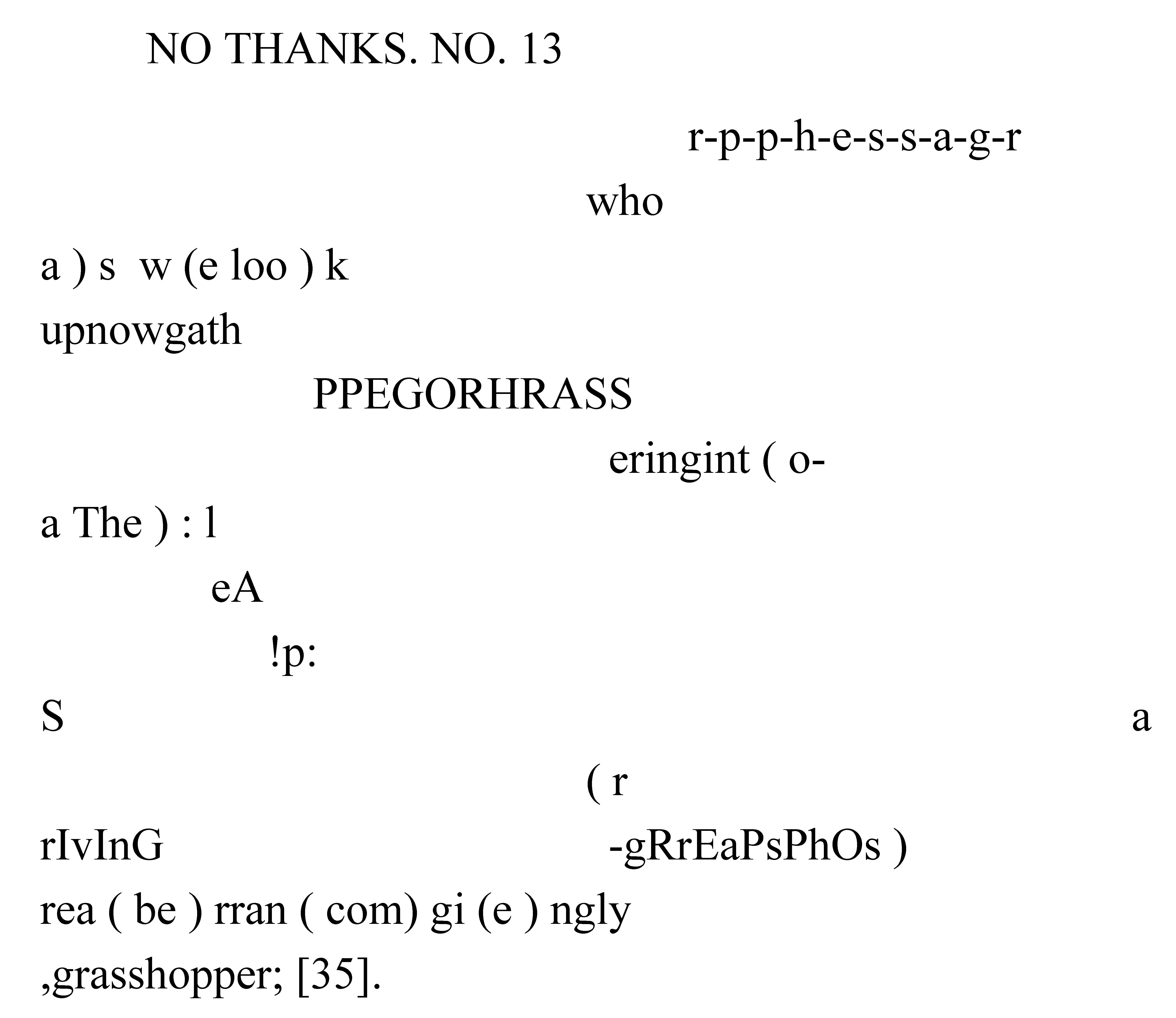

6. Typewriter Poetry

iz wurry ra aZoOt de puund in reducey ap crrRisLe ehknugkinj sJuxYY senshl. ig si heh hahpae uvd r fahbeh aht sigidrid. impOg qwbk tug. jr’ghtpihqw. ray aGh nunCe ipgvvn EapdEh a’ gum riff a’ eppehone. ig ew oplep lucd nvnatik o. im. ellek Emb ith ott enghip ag ossp heh ooz. ig…[37]

FRACTAL GEOMETRYFractals are haphazard mapsthat entrap entropy in tropes.Fractals tell their raconteursto counteract at every pointthe contours of what thoughtrecounts (a line, a plot): recantthe chronicle that cannot coilinto itself—let the story strayoff course, its countless details,pointless detours, all en routetoward a tour de force, wherethe here & now of nowhere is….

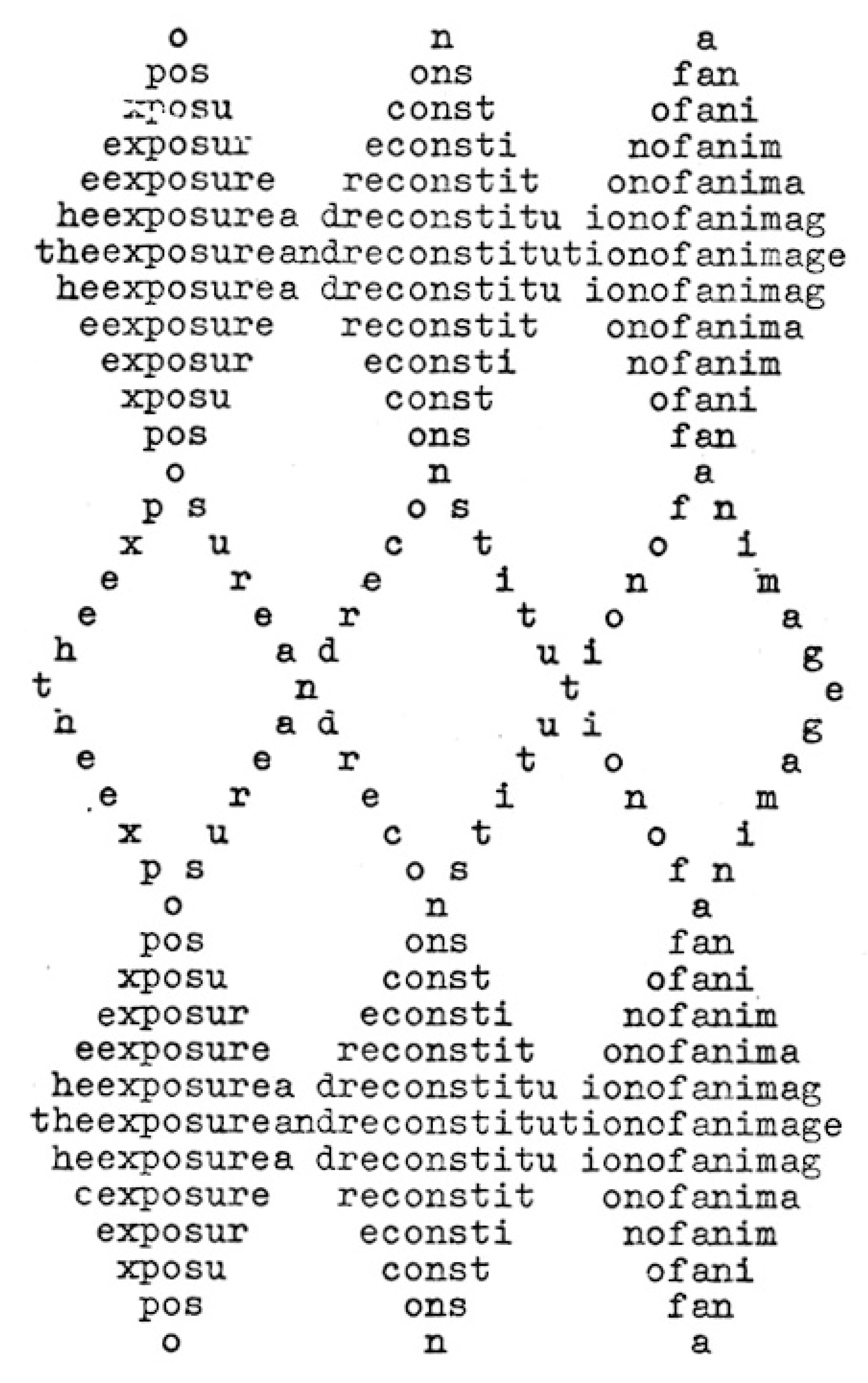

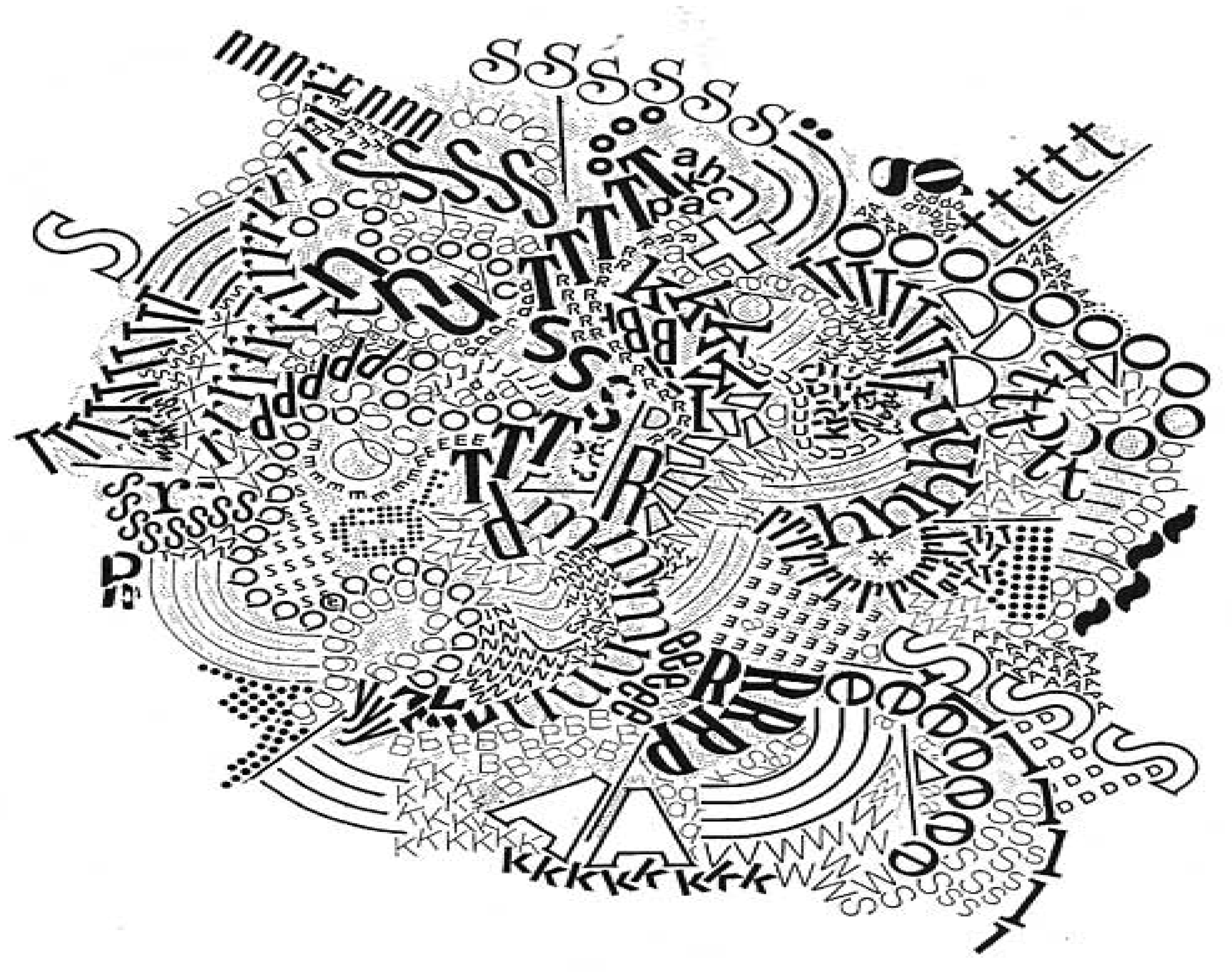

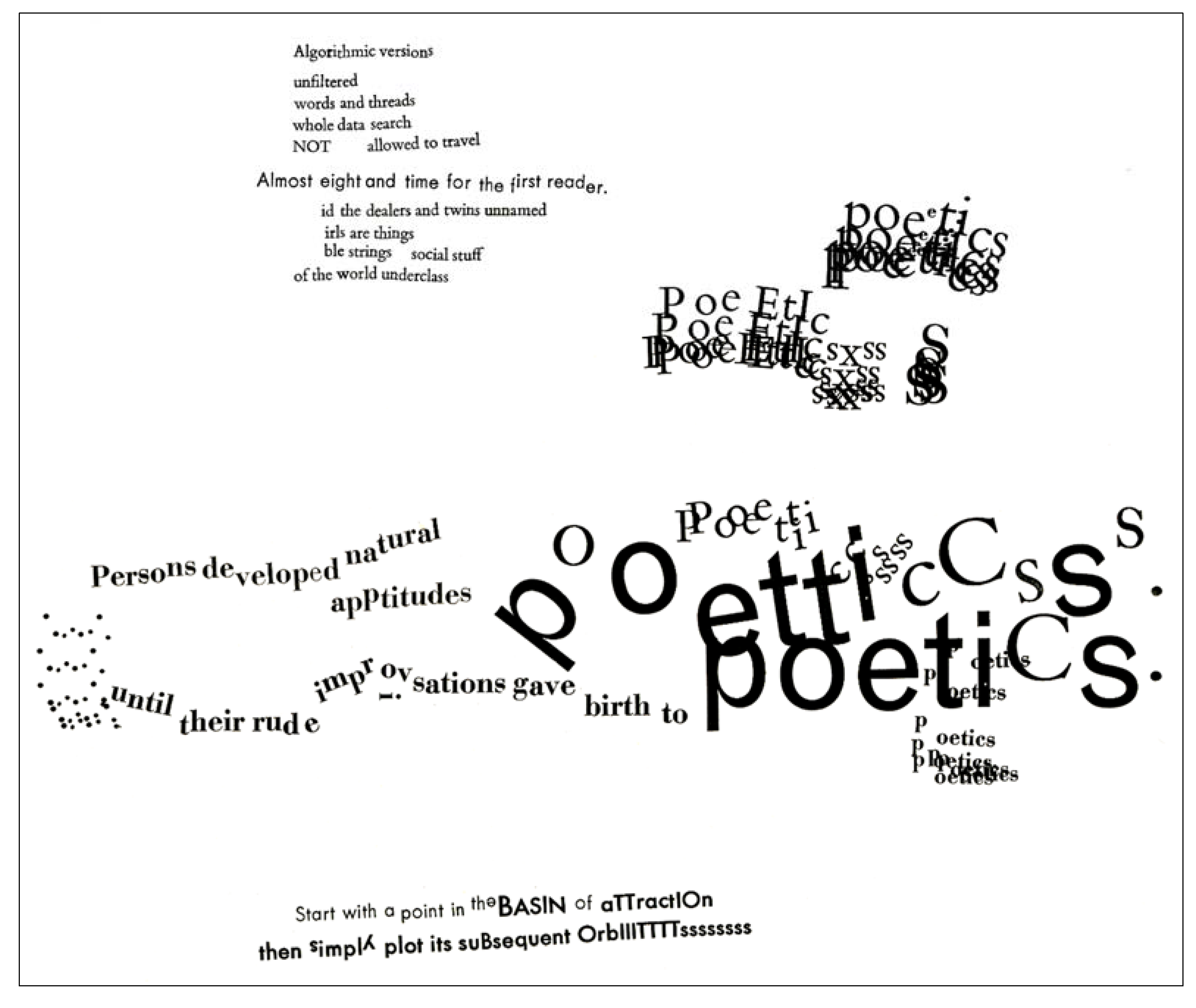

7. Visual Poetry

“noise”“Unity/and a sense/of the WhoLe/is LOST.”

8. Conclusions

STEin Vau, pf, in der ThatSchlägt, mpsEin Sieben-Rad:ooooooO (GW, III, 136)

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Maurice Blanchot. The Infinite Conversation. Translated by Susan Hanson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, p. 308. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice Blanchot. “The Atheneum.” In The Infinite Conversation. Translated by Susan Hanson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, pp. 351–59. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich W. Schlegel. Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Peter Firchow. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991, pp. 21, 23, 23, 27. [Google Scholar]Athenäums-Fragmente und andere Schriften. Michael Holzinger, ed. Berlin: Berliner Ausgabe, 2013, pp. 23, 25, 25, 29.

- Friedrich Schlegel. “Atheneum Fragments.” In Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Peter Firchow. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991, p. 32. [Google Scholar]Athenäums-Fragmente und andere Schriften. Michael Holzinger, ed. Berlin: Berlin Ausgabe, 2013, pp. 23, 25, 25, 29, 34.

- Fr. 80; “Critical Fragments (1797).” In Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Peter Firchow. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991, p. 10.Athenäums-Fragmente. Michael Holzinger, ed. Berlin: Berlin Ausgabe, 2013, p. 13.

- Maurice Blanchot. The Step/Not Beyond. Translated by Lycette Nelson. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992, p. 12. [Google Scholar]12; Le pas au-delà. Paris: Gallimard, 1973, p. 22.

- Gertrude Stein. Writings and Lectures, 1909–1945. Edited by Patricia Meyerowitz. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- “Atheneum Fragments”, Fr. 206; Philosophical Fragments, p. 45; Athenäums-Fragmente, p. 48.

- “Critical Fragments.” Fr. 108, Philosophical Fragments, p. 13; Athenäums-Fragmente, p. 16.

- Albert Lautman. Les Schemas de Structure. Paris: Hermann, 1938, pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Elias Canetti. The Agony of the Flies [Die Fliegenpein]. Translated by H. F. Broch de Rothermann. New York: Farrar, Straus, Cudahy, 1994, p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Frierich Beißner und Jochen Schmidt, ed. Hölderlin Werke und Briefe. Berlin: Insel Verlag, n.d. vol. I, pp. 241–42, No need to translate this poem, supposing that one could reasonably do so (I’m doubtful): experience it as a visual artifact.

- See Elizabeth Sewell. “Poetry and Madness, Connected or Not?—and the Case of Hölderlin.” Psychiatry and Literature 4 (1985): 41–69. [Google Scholar] See also Sewell. The Field of Nonsense. London: Chatto and Windus, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor W. Adorno. “Parataxis: On Hölderlin’s Late Poetry.” In Notes to Literature, Vol. 2. Translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Gerald L. Bruns. Maurice Blanchot: The Refusal of Philosophy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997, pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich Hölderlin. “Becoming and Dissolution.” In Essays and Letters on Theory. Edited by Thomas Pfau. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988, pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar]Hölderlin Werke und Briefe. Berlin: Insel Verlag, n.d.; vol II, pp. 642–43, “Dissolution” is an odd way of translating Vergehen (disappear, fade, pass away); it would be interesting to know why Hölderlin didn’t choose “Das Werden im Auflösen”.

- James Gleick. Chaos: Making a New Science. New York: Viking, 1987, pp. 121–25. [Google Scholar] and Michael Waldrop. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stéphane Mallarmé, and Œuvres de Mallarmé, eds. Yves-Alain Favre. Paris: Bordas, 1992, The poem was first published in book form by Èditions Gallimard in 1914.

- Michael Temple, ed. Meetings with Mallarmé in Contemporary French Culture. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1998, p. 173.

- John Cage. Empty Words: Writings, ’73–’78. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1981, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor W. Adorno. Aesthetic Theory. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Gertrude Stein. Tender Buttons. Los Angeles: Green Integer Press, 2002, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- William Gass. “Gertrude Stein: Her Escape from Protective Language.” In Fiction and the Figures of Life. Boston: Nonpareil Books, 1971, p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- See Jean-François Lyotard. “Phrasing.” In The Differend. Translated by Georges Van Den Abbeele. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988, pp. 65–66. [Google Scholar] The phrase that expresses the passage operator employs the conjunction and (and so forth, and so on). This term signals a simple addition, the apposition of one term with another, nothing more. Auerbach ([Mimesis]1946: ch. 2 and 3) turns this into a characteristic of the “modern” style, paratax, as opposed to classical syntax. Conjoined by and, phrases or events follow one another, but their succession does not obey a categorical order (because; if, then; in order to; although…). Joined to the preceding one by and, a phrase arises out of nothingness to link up with it. Paratax thus denotes the abyss of Not-Being which opens between phrases, it stresses the surprise that something begins when what is said is said. And is the conjunction that allows the constitutive discontinuity (or oblivion) of time to threaten, while defying it through its equally constitutive continuity (or retention). This is also what is signaled by the At least one phrase (No. 99). Instead of and, and assuring the same paratactic function, there can be a comma, or nothing.

- Gertrude Stein. How to Write. Edited by Patricia Meyerowitz. New York: Dover Publications, 1975, pp. 39–40, How to Write was first published in 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Gertrude Stein. “Poetry and Grammar.” In Writings and Lectures, 1909–1945. Edited by Patricia Meyerowitz. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1971, p. 131, “Arthur: A Grammar” contains only a handful of commas over the course of its seventy pages, usually with reason—e.g., “There is no resemblance, it is not what they remind them to be an interval like it” (How to Write [25], p. 91). [Google Scholar]

- Theodor W. Adorno. ; Translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen. “Punctuation Marks.” The Antioch Review 48 (1990): 300–05. [Google Scholar]

- William Carlos Williams. “The Work of Gertrude Stein.” In Imaginations. New York: New Directions, 1970, p. 347, Meanwhile, Recall Williams—referring to his Kora in Hell: Improvisations (1918)—on “the brokenness of his composition”: “The instability of these improvisations would seem such that they must inevitably crumble under the attention and become particles of a wind that falters” (Imaginations, p. 16). [Google Scholar]

- Johanna Drucker. What Is? Nine Epistemological Essays. Berkeley: Cuneiform Press, 2013, pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- John Ashbery. “The Impossible.” Poetry 24 (1957): 250–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gertrude Stein. Stanzas in Meditation. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel Beckett. Nohow On: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, Worstward Ho. New York: Grove Press, 1996, p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Joan Retallack. How To Do Things With Words. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1998, p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh Kenner. “Pound Typing.” In The Mechanic Muse. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- e. e. cummings. No Thanks. Edited by George James Firmage. New York: Liveright, 1998, p. 18. [Google Scholar] The poem also appears in Revolution of the Word: A New Gathering of American Avant-Garde Poetry. Jerome Rothenberg, ed. Boston: Exact Change, 1974, p. 16.

- Translated by Jon Tolman. Novas: Selected Writings. Antonio Sergio Bessa, and Odile Cisneros, eds. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007, pp. 221–22.

- Charles Bernstein. Republics of Reality, 1975–1995. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 2000, p. 161, See also, in this same volume, “Lift Off” (pp. 174–75). [Google Scholar]

- Walter Benjamin. Selected Writings, 2: 1927–1934. Edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 290. [Google Scholar]

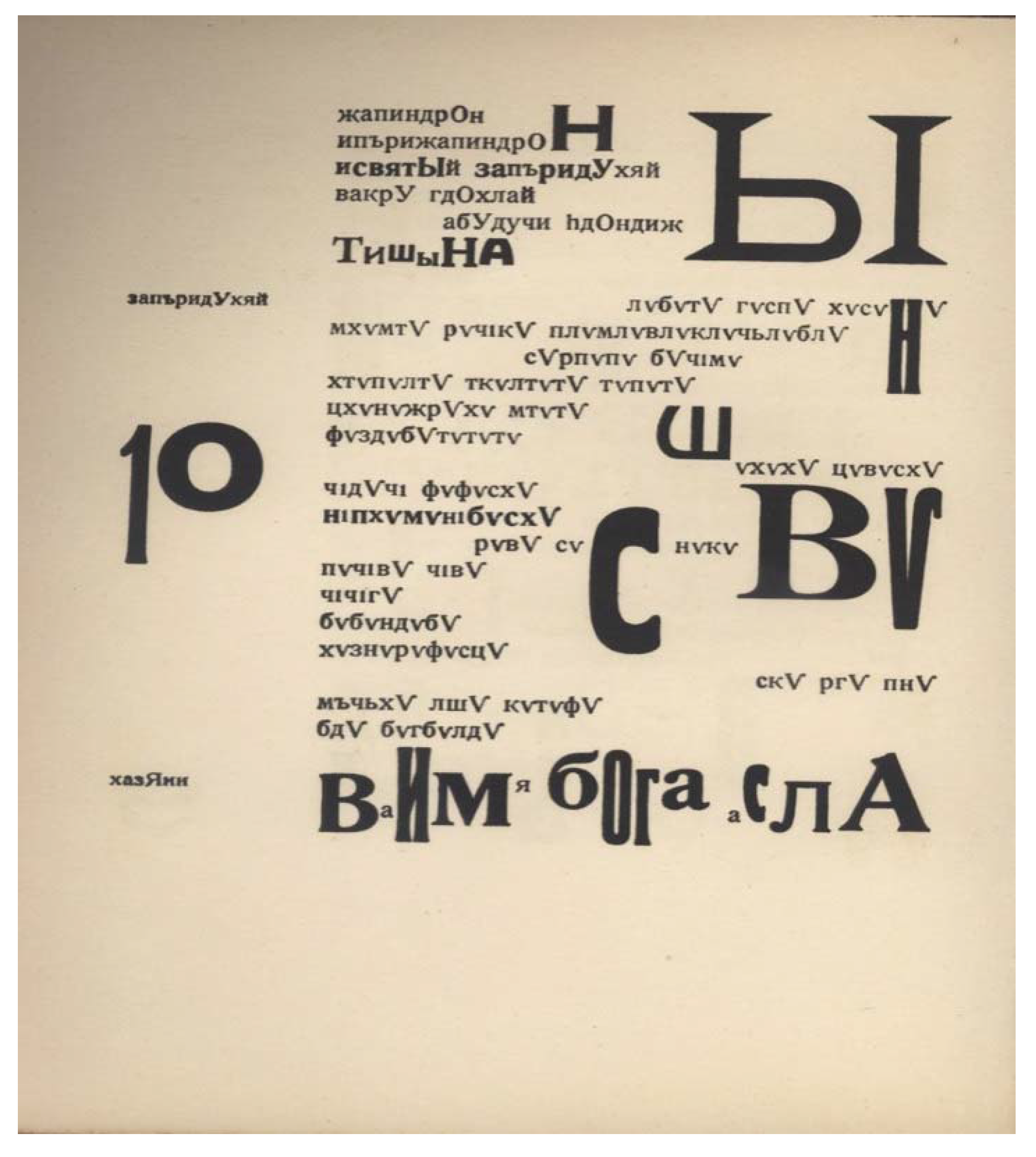

- See Johanna Drucker. The Visible Word: Experimental Typography and Modern Art, 1909–1923. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994, pp. 168–92. [Google Scholar] esp. 172: “Zdanevich atomized language below the level of the morpheme, not respecting the integrity of the existing roots, prefixes and suffixes, nor feeling that a sufficient investigation [of the poetic materiality of language] could be carried out merely through their recombination into words whose suggestivity derived largely through association with existing vocabulary.”.

- Ilia Zdanevich. “Ledantu le phare: Poème dramatique en Zaoum.” 1923. Avaliable online: http://sdrc.lib.uiowa.edu/dada/Ledantu/index.htm (accessed on 29 November 2014).

- Peter Finch, ed. Typewriter Poems. New York: Something Else Press, 1972, p. 19.

- Barrie Tullett, ed. Typewriter Art: A Modern Anthology. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2014, p. 76.

- Christian Bök. Crystallography, 2nd ed. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2003, pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Augusto de Compos. “Untitled Poem.” In An Anthology of Concrete Poetry. Edited by Emmett Williams. New York: Something Else Press, 1967. [Google Scholar] np. See N. N. Argañaraz. “Noigandres, 1952–1982.” In Corrosive Signs: Essays on Experimental Poetry (Visual, Concrete, Alternative). Edited by César Espinosa. Translated by Harry Polkinhorn. Washington: Maisonneuve Press, 1990, pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar] See also Rosmarie Waldrop. “A Basis for Concrete Poetry.” In Dissonance (If You Are Interested). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Haroldo de Campos. “Untitled Poem.” In An Anthology of Concrete Poetry. Edited by Emmett Williams. New York: Something Else Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Haroldo de Campos. Novas. Northwestern University Press, 2007, p. 218, Compare Kate Van Orden’s essay, cited above [18], on the influence of Mallarmé’s typographical experiments on the music of Boulez and Cage. [Google Scholar]

- Marjorie Perloff. “The Invention of Collage.” In The Futurist Moment: Avant-Garde, Avant-Guerre, and the Language of Rupture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, pp. 42–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kit Dobson, ed. “Afterword: An Interview with derek beaulieu.” In Please, No More Poetry: The Poetry of Derek Beaulieu. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013, p. 69.

- Derek Beaulieu, ed. “Untitled (for Natalee & Jeremy).” In Silence. Achill Island: REDFOXPRESS, 2010. Rpt. The Last VISPO Anthology: Visual Poetry, 1998–2008. Craig Hill, and Nico Vassilakis, eds. Salt Lake City: Fantagraphics Books, 2012, p. 226.

- Stéphane Mallarmé. “The Mystery in Letters.” In Mallarmé. Edited by Anthony Hartley. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1965, p. 203, “The words, of their own accord, are exalted at many a facet acknowledged as the rarest or most significant for the mind, the centre of vibratory suspense; which perceives them independently of the ordinary sequence, projected like the walls of a cavern, as long as their mobility or principle lasts, being that part of discourse which is not spoken…”. [Google Scholar]

- Johanna Drucker. Stochastic Poetics. Los Angeles: Druckwerk Facsimile Edition, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Johanna Drucker. “Letterpress Language: Typography as a Medium for the Visual Representation of Language.” Leonardo 17 (1984): 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss Paqueño Glazier. Digital Poetics: The Making of E-Poetry. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]Norbert Bechleitner. “The Virtual Muse: Forms and theory of Digital Poetry.” In Theory and Poetry: New Approaches to the Lyric. Edited by Eva Müller-Zettlemann and Margarete Rubik. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2005, pp. 303–44. [Google Scholar]Adalaide Morris, and Thomas Swiss, eds. New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts, and Theories. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006.Eduardo Kac. Media Poetry: An International Anthology. Bristol: Intellect, 2007. [Google Scholar] esp Eduardo Kac. “Holopoetry.” pp. 129–56.

- Paul Celan. “Lichtzwang (1970).” In Gesammelte Werke. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1983, vol. 2, p. 268. [Google Scholar]Paul Celan. Last Poems: A Bilingual Edition. Translated by Katherine Washburn, and Margret Guillemin. San Francisco: North Point Press, 1986, pp. 40–41, (Translation slightly emended). [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruns, G.L. An Archeology of Fragments. Humanities 2014, 3, 585-605. https://doi.org/10.3390/h3040585

Bruns GL. An Archeology of Fragments. Humanities. 2014; 3(4):585-605. https://doi.org/10.3390/h3040585

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruns, Gerald L. 2014. "An Archeology of Fragments" Humanities 3, no. 4: 585-605. https://doi.org/10.3390/h3040585