1. Introduction

The goal of every global company is to grow steadily and gain maximum market share. These companies are characterised by a complicated set of operations, emphasis on quality, brand awareness, and high quality staffing. This can be effective if the setup of the organisational structure is fully in line with the nature of the market and the product portfolio. The organisational structure of global companies is evolving over time, but they are currently similar in all companies across all segments. Considering the trends of changes within Industry 4.0, the central issue in Economy 4.0 is to understand the impact of digital transformation, the creation of the connection networks, and to adapt business models to increasingly demanding customers.

Corporate companies operating on the global market are, generally, geographically divided into several zones, and then further broken down. Most companies in the European area fall into a zone called Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA). This zone is then further divided into regions. The EMEA zone contains a large number of countries with different purchasing power, size, and maturity. Its role, in terms of business and corporate governance, is also played by religious, historical, and cultural context.

Such a varied zone requires different business and marketing strategies (

Porter 1996;

Alford and Greve 2017). The business model can be divided into two basic types: direct and indirect (more in

Honeycutt et al. 2003;

Kotler et al. 2007;

Kim et al. 2018). With direct sales, the company is represented in the country as a local company with a local organisational structure. Depending on the size of the country, the purchasing potential, and the amount of sales, all components of the company—such as sales, marketing and finance departments, technical and customer support, and more—are present in the country. In smaller countries, global companies have only a fraction of the components present, such as business and finance departments, and all others are shared across multiple countries. In the indirect sales model, the companies are represented by partners or, in certain cases, distributors. Collaboration may take several forms, two of which are exclusive and non-exclusive. The first is exclusive cooperation, in which the distributor is the exclusive and only sales channel in the country. This model is on the decline because, in times of crisis, global firms have a very limited scope for change in response to a situation. That is why the second collaboration model, non-exclusive cooperation, is used more extensively. In this model, a global company does not commit itself to exclusivity and, if necessary, can enter the market directly or use different sales channels (

Salvioni et al. 2016).

If we focus on a direct representation business model for global companies, in a given country, a key factor in sales efficiency is setting up a good business structure (see

Kraus et al. 2018). Selecting a suitable model depends on several parameters. It is often very difficult to choose the right one. In many companies, after the introduction of one model there may be a transition to another, after a very short period of time, as expectations have not been met or other elements motivate the company to change. One of these elements may be a rapid increase in costs, which negatively affects the financial soundness of the company from different areas, such as profit and cash flow.

Determining the sales structure and the number of sales people that will be most effective is a complex and important decision. It is a decision that determines the success and failure of a company in the short, medium and, if there are no changes, long-term (

Andrews et al. 2017;

Schumacher 2013;

Farah and Gomez-Ramos 2014).

The main aim of this article is to describe and evaluate the introduction of a territorial business structure. The first partial aim is to focus on a territorial business structure within the framework of a global company in the Czech Republic. The second partial goal is to define the key attributes necessary to set up a new business structure according to territorial management. The authors focus on reorganising the organisation. Furthermore, the authors evaluate the final effect of the whole reorganisation and generalise the process of setting up the territorial business infrastructure for global businesses.

Setting up the sales model is not a rigid thing and can be changed while running the company. Each change is, however, associated with two major negative effects that are intertwined. The first is, in most cases, the reluctance of people in the sales department to embrace change. This reluctance has a secondary effect, which is a short-term decline in turnover. However, after a certain period, there is a turnaround and subsequent growth, assuming that the direction determined by the change is the correct one. The length of this period depends mainly on management and how they can motivate and persuade individual members of a business team that a new vision and a new model bring a more positive future for them and for the company. This can be brought in the form of competitiveness, increase of the market share, and turnover, over the long-term.

2. Methodological Background for the Introduction of Territorial Management

There are quite a number of ways to break down the competencies and organisation of work in a company. Each of the organisational structures is suitable for a different type of business, and each has its practical application. It is therefore not possible to say which of the alternatives is the right one and the most effective. However, it is correct to say that the organisational structure is definitely not, or at least should not be, something unchangeable (

Kovacs and Kot 2016). The company naturally changes with time: its portfolio of products and services, the number of employees, their experience, and so on, all change. It is important that all these changes are reflected in how work is managed and organised within the company. The most frequent factor in changing the organisational structure can be the growth in the number of employees or the new market situation (

Teplicka et al. 2015;

Darmanto et al. 2017;

Okreglicka and Mynarzova 2015;

Kasik and Snapka 2015).

When designing and choosing a particular model, it is also necessary to take into account personality skills in general, such as the ability of a manager to manage a certain number of employees with some efficiency and attention. According to Graicunas’ theory (

Veber 2000;

Zikmund 2010,

2011), one leader is able to manage a maximum of five subordinates. As soon as they have more, they are quickly freed of certain relationships, and the situation and subordinates can easily get out of control or, on the contrary, the subordinates may miss the leadership and attention that the manager should provide them. Therefore, if a company does not change its organisational structure at the appropriate moment, it may stumble at a certain stage of its development or even begin to stagnate (

Dedina and Maly 2005;

Pachura 2017).

Territorial sales arrangement—a sales team divided by geographical territory.

Product sales—a sales team divided by products or product groups.

Sales by individual markets.

Combination of previous models.

The territorial organisation of sales is based on the fact that each sales person is in charge of a certain geographical area with a precisely defined set of customers, where the products offered are the complete portfolio of the company. This model brings with it many advantages, especially a clear customer list structure, customer segmentation, possibility to quantify the potential of the territory, direct responsibility of the seller for the given sales management in the given territory, simple implementation of Key Account Management for the company as a whole, and a reduction in travel costs.

The product layout is based on the fact that each sales person is in charge of only a part of the company’s products. This arrangement is primarily chosen by companies that have many products of different kinds that are also very distinctive and technically complex. It is also used in sectors where a highly skilled sales person who knows the products in great detail is an added value, and an advisory style, mostly from a technical or application point of view, is used more than commercially-driven business relations (

Dedina 1996;

Spaho 2010;

Lin et al. 2018).

The sale by individual markets is characterised by the fact that the sales territories are established according to the market served—industrial, food, or other segment—or even the composition of customers themselves ,which are close in their profile (e.g., sales representatives for the automotive industry, and so on).

Purchasing power and the size of market.

Competitive environment and clusters of competing companies.

Anticipated turnover in several years and in different outcome variants.

Analysis of the sales portfolio, with emphasis on the key products.

Analysis of the sales territories.

Customer analysis, customer segmentation, or potential for individual customers.

The size of the total sales territory.

The estimated costs associated with the sale of the P&L (profit and loss statement) of the sales department.

Pricing policy: market prices, product pricing, and separation of the top products from the perspective of pricing.

The basic methods and techniques used to create a new organisational structure according to the territorial management include: recency, frequency, and monetary value, customer value, lifetime value of customers (

Fader et al. 2005), complete analysis of competition in terms of substitutions, product portfolio, price comparisons, added value (

Lenzo et al. 2018;

Ali et al. 2018;

Ballance et al. 1987) (i.e., competitive advantages), the SWOT analysis of each competitor, finding competitive advantages, eliminating weaknesses against competitors, and finding market space. In addition, it is necessary to prepare an action plan with clear objectives and strategies, to set up a network analysis with the setting of individual control points at the time of recapitulation of success or failure, and a plan for individual customers in terms of prices and product offerings, based on customer needs analysis (

Chytilova 2015).

3. Reorganisation According to the Territorial Management

A global company acting in the field of health has set ambitious growth targets over the medium term. One component was to streamline company operations and business models at local levels. The second was subsequent acquisitions.

Long-term and ambitious growth can only be achieved by executing pre-prepared changes, both globally and in individual countries. That is why, in the first phase, a complete change of the internal structure in all the components of the company took place. The second phase, which is the subject of this thesis, is the setting up of a new business model at the national level in the Czech Republic and the introduction of business management standards. At the final stage, once the company’s operations have been set up, as well as a new business model, it is still possible to move on to acquisition activities.

Creating an efficient and fully functional business structure is a demanding process that requires a clear and long-term vision that is in line with the vision of the whole company. The whole process must have a clear timetable. Any deviations from the plan in the process of reorganisation can result in fatal consequences.

The basic steps in introducing the territorial business model and business standards can be described by the following points. Only this complex system is fully functional, long-term, and efficient:

Setting up the Territory Management.

Collaboration with distributors and integrators.

Create a Sales Support Specialist position and introduce him or her into a team.

Introducing the CRM (Customer relationship management) system and introduction of reporting and forecasting.

Introduction of financial reports.

Set up of the Funnel Management aimed to effectively manage commerce.

Introducing the Customer Segmentation and creating the Key Account Management.

In this article, the authors will focus on the first three steps: setting up the territorial business model, creating a sales network with distributors for a selected product group and for a defined business opportunity, and creating a new Sales Specialist position, with subsequent implementation of the entire team.

Territorial breakdown was made on the basis of historical sales to individual customers in order to set up three geographical areas with an equal turnover (33%, 33%, and 34% of total turnover) and a similar customer structure in terms of size and sales potential. An integral part of the setup is also taking into account the cost of the new model and, on the other hand, increasing the efficiency of the sales representatives. This can be increased by minimising the time spent on the road and by increasing the number of negotiations within a defined time horizon.

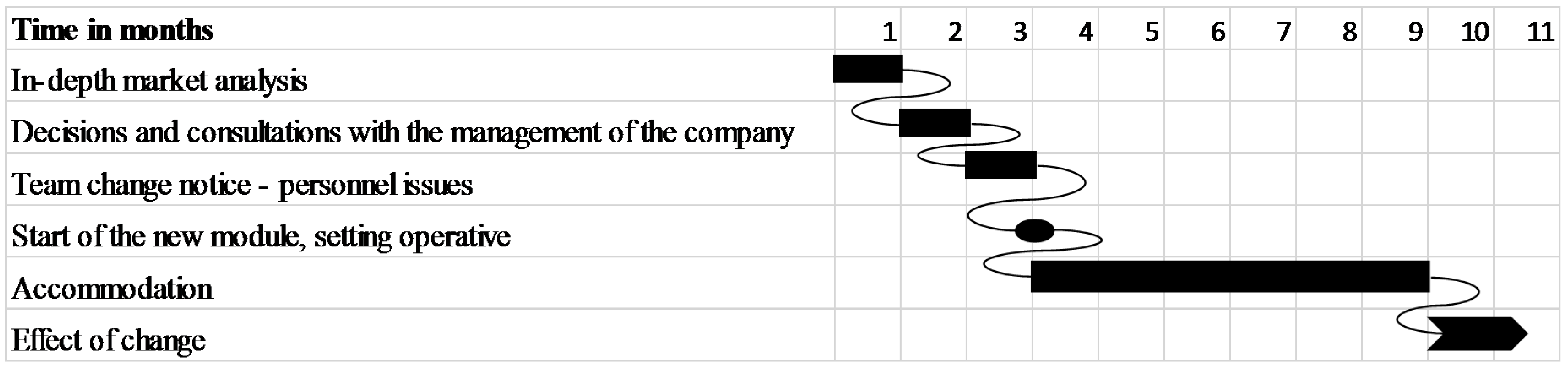

In the Gantt’s diagram (see

Figure 1), the process of setting up the Territorial Business Model is captured:

In-depth market analysis: 2 weeks to 1 month.

Decisions and consultations with the management of the company: 1 month.

Team change notice and personnel issues: 1 month.

Start of the new module, setting operative: after 3 months.

Accommodation, decrease in performance, decrease in productivity, and in sales: 6 months.

Effect of change, growth of performance, productivity growth, and efficiency: after 9 months.

Setting up a new model is a time-consuming process that runs continuously. The implementation of some of the above points is intertwined, but the first is to set territories including a list of customers. This is followed by all further steps and set-up of the entire business operation, such as reporting, forecasting, introducing a CRM system, and so on. The territory’s own set-up, based on sales analyses, lasted for weeks; the whole implementation took months. Throughout, all steps have been tracked, evaluated, and eventually modified to avoid demotivating people and reducing their performance. The entire process was run by the management, and the local manager was fully responsible for the implementation.

Three territories for three sales representatives were created to achieve the goal. Two located in Prague, geographically divided in Prague and the Bohemian region. The third person resided in the city of Olomouc to minimise travel, and for this reason a new employee model—Home Office—was created within the company (

Figure 2. Map of the Territorial Division). This model requires much more rigorous work with the CRM model, increased frequency of communication between individual team members, and setting up the regular personal team meetings.

Figure 2 shows the division of the Czech Republic into three sales territories. Two business representatives are based in Prague (blue location) and one in the Home Office work model in Olomouc (red location). In addition to the even distribution of customers and the level of sales, this division also resulted in an even travel burden.

All the sales representatives are in charge of the same product portfolio, which allows you to compare business results, track development and product structure, and reflect on each territory, which may have certain fluctuations and specifics.

A supportive position called Sales Support Specialist was created to complete a functional sales team. The person is in charge of all the administrative assurance of the business team. Centralising the creation of all business offers, bidding for the tender under this feature has made business processes more transparent, streamlined the way the business team works, and given sales representatives the opportunity to spend more time with customers.

Along with setting up business territories, it was necessary to set up distributors for two purposes. The primary purpose is to transfer a non-speculative product line that does not belong to the company’s core product stream under a dedicated business partner, and to create a secondary partnership for complex public procurement, to which we do not enter as integrators.

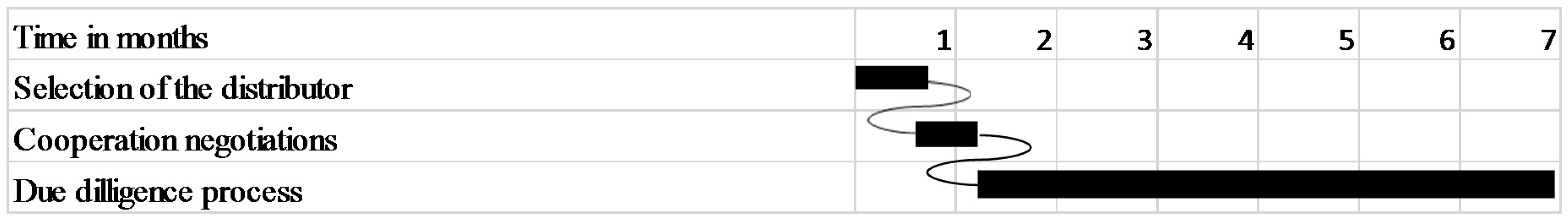

The selection process for distributors takes place in several phases captured in the following diagram (

Figure 3). The first phase—the selection of the distributor—lasts about 2 weeks, depends on market knowledge, and market analysis (market share, distributor power, and product portfolio). The next step is cooperation negotiations, approval process, and the due diligence process, which lasts 6 months (dealing with the distributor’s property structure, turnover, and account statements).

Nowadays, trust-based management plays an increasingly important role in the life of enterprises. Management must be able to adapt with flexibility to varied situations and, when necessary, to change between different styles of leadership. The rapid development of the European Community and the economic integration of the member states produces a strong need for managers who can understand and adapt to cultural differences in work-related values and leadership (

Oláh et al. 2017b). The choice of suitable partners is crucial, as long-term cooperation is expected. In addition, global companies have an authorisation process for distributors called due diligence. This process is relatively lengthy and costly and includes management and legal departments. Therefore, partner selection is also a strategic decision. In this case, they were selected on the basis of their market position. For the first purpose, i.e., the distribution of the non-speculative line, the most powerful player on the market in the segment was selected, which has no overlapping competitive solution in its portfolio. As a partner for complex public procurement, a distributor has been selected, which has the broadest portfolio on the market. This has resulted in the highest number of tenders, in which we have been able to enter.

By creating these collaborations with local business partners, in the first case, the opportunity to fully focus on a profitable part of the product portfolio was created, and in the second, we have been given the opportunity to enter into complex tenders under the auspices of strong local integrators.

4. Conclusions

All companies in the market must monitor their development and respond to it. Local companies have an advantage in this regard, as the decision line is straightforward. Global companies are relatively rigid in this respect, and the implementation of any changes is strategic in terms of time and financial execution over all countries. Changing organisational structures is one of the most demanding as it also affects human resources. Changing the business model is all the more demanding as it changes the part of the company that is in direct contact with customers. The actual turnover is directly affected by it.

For companies, trust has a decisive importance. The quantity of communication, good performance, the capacity to meet expectations and be at the customer’s disposal, and fulfilment of payment obligations all increase the level of trust in a partner. This specific knowledge (deep knowledge of each other) and the timely provision of information results in a high level of flexibility in the relationship. (

Oláh et al. 2017a).

The described parameters of the territory model combined with the creation of a new Sales Support position supporting sales representatives and creating a new business network in the form of business partners resulted in a year-to-year decline in sales in percentage points in the current year in which the overall change took place. This decline was expected given the rapid changes and overall accommodation of both the internal system and customers. In the following year, the positive effect of the newly set-up overall system was known, as sales grew by more than 20% year-over-year and had historically the best trading result.

The Accenture Technology Vision 2017 annual report predicts that within five years, classical employment will retreat the temporary recruitment of outsiders, and all sectors will dominate companies with cut-off bureaucracy, a small core, and a strong ecosystem of experts (

Accenture Technology Vision 2017). Accenture believes that call work will be the main engine of growth for most economies and will gradually replace corporate organisational structures and management models.

Territorial organisation and the newly created system appears as highly efficient and long-term, and not only for the described company. It also allows you to create a functional CRM model with the ability to manage your business with the Funnel Management method. Centralising all business administrative activities and documents results in simplicity in other areas such as ISO audits, financial audits, both external and internal. It also facilitates simple and central receipt of phone calls from customers and readability of the company on the market. This territorial set-up corresponds to predicted market trends and is suitable for global businesses.

The outcomes of the research emphasize and justify the importance of reorganising the organisation. Reorganization of companies has emerged as a new trend in recent years. The first step is to examine whether there is any significant difference in terms of organisational business structure and its management style. In order to do that, the variance of each category has to be analyzed. Hence, it is necessary to observe whether there is any correlation between the level of personality skills in general and the flexibility of territorial management.

As a suggestion in relation to the future research, it is necessary to see how the territorial model could be connected with Enterprise Resource Planning and Customer Relationship Management.

Setting up a suitable business model is a strategic decision of the company and is a key to its overall development. It is fully within the competence and responsibility of the management of the company as it involves not only with the company’s sales results, but also penetrates into the overall operation and affects all the employees in the company as well as the customers. The described example of the implementation of the Territorial Settlement of the Sales Department points to the suitability in the given environment and the complexity of the whole process. It is transferable to other companies and can be used as a model example.