Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to examine the moderation of parental mediation in the longitudinal association between being a bystander of cyberbullying and cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization. Participants were 1067 7th and 8th graders between 12 and 15 years old (51% female) from six middle schools in predominantly middle-class neighborhoods in the Midwestern United States. Increases in being bystanders of cyberbullying was related positively to restrictive and instructive parental mediation. Restrictive parental mediation was related positively to Time 2 (T2) cyberbullying victimization, while instructive parental mediation was negatively related to T2 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Restrictive parental mediation was a moderator in the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization. Increases in restrictive parental mediation strengthened the positive relationship between these variables. In addition, instructive mediation moderated the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization such that increases in this form of parental mediation strategy weakened the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization. The current findings indicate a need for parents to be aware of how they can impact adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying as bullies and victims. In addition, greater attention should be given to developing parental intervention programs that focus on the role of parents in helping to mitigate adolescents’ likelihood of cyberbullying involvement.

Keywords:

cyberbullying; bystander; bystanding; victimization; perpetration; bully; parental mediation 1. Introduction

Cyberbullying is often conceptualized as a dyadic conflict between the perpetrator and victim, although adolescents can have other roles (e.g., defender, bystander) in these conflicts. Research on bystanders of cyberbullying is increasing, especially because toxic stress can result from witnessing cyberbullying (Rivers et al. 2009). Such toxic stress might reduce bystanders’ use of effective coping strategies, leading to their involvement in cyberbullying. Researchers have focused on factors that might reduce adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying (Hinduja and Patchin 2008; Rivers et al. 2009). One such factor is parental mediation, and it influences adolescents’ cyberbullying involvement (Livingstone and Helsper 2008; Navarro et al. 2013; Sasson and Mesch 2017; Wright 2018), although it is unclear how parental mediation might impact the likelihood of being a bystander of cyberbullying. It is also unknown whether parental mediation might diminish the likelihood of bystanders of cyberbullying becoming cyberbullying perpetrators or cyberbullying victims. The purpose of the present study was to examine the moderation of parental mediation in the longitudinal associations among being a cyberbullying bystander, perpetrator, and victim. The findings of this study contribute to the field of cyberbullying by explaining the role of parental mediation in cyberbullying bystanding, perpetration, and victimization.

1.1. Cyberbullying: Perpetrators, Victims, and Bystanders

Defined as the deliberate and repetitive infliction of harm through digital technologies (e.g., email, online gaming, gaming consoles, mobile devices, instant messenger, social networking websites), cyberbullying involves an imbalance of power (Hinduja and Patchin 2008). Cyberbullying includes embarrassing, intimidating, harassing, outing, and social exclusionary behaviors (Ferdon and Hertz 2007; Grigg 2010; Kowalski and Limber 2007; Topcu et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2011; Wolak et al. 2007; Ybarra et al. 2007). Through digital technologies, cyberbullies are able to victimize others at almost any time without concern for the consequences of their actions (Wright and Li 2013; Wright 2014). Anonymity of the online environment can trigger adolescents’ inability to constrain or restrain their behaviors, which makes them susceptible to cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Suler 2004; Udris 2014; Wright 2014).

A bystander of cyberbullying is defined as an adolescent who sees/witnesses the behavior occurring between the cyberbully(ies) and cybervictims(s), but decides not to get involved in the situation (Wachs 2012). Witnessing cyberbullying as a bystander is one of the most common ways to experience cyberbullying. Rates of witnessing cyberbullying in adolescent samples ranges from 30% to 60% (Huang and Chou 2010; Van Cleemput et al. 2014; Vandebosch and Van Cleemput 2009); variations in these rates most likely reflect different sampling and measurement techniques. Bystanders of cyberbullying are less likely to report cyberbullying to adults than bystanders of offline bullying (Smith et al. 2008). Such a finding is especially concerning as the online world of adolescents includes fewer adults than their offline world, adolescents may or may not know the cyberbully(ies) or cybervictim(s), and that cyberbullying can include an infinite number of bystanders. These features of the online world of adolescents might reduce the likelihood of them reporting the situation.

Understanding more about bystanders of cyberbullying is important as the purpose of bullying is often to diminish victims’ social standing among their peer group as a means of exerting dominance and gaining status in the peer group (Wright 2015). Sometimes the intent of cyberbullying behaviors is to not only target the victim directly, but to also influence bystanders to eventually become involved in an effort to further humiliate and prolong the attack. The reasons adolescents do not intervene in cyberbullying are complex. Many adolescents might not feel responsible for the bullying behavior, fear unfavorable judgement by peers for intervening, not realize that the situation is perceived as uncomfortable, and they might lack the skills to intervene (Wachs et al. 2015). When bystanders remain passive, they are giving the impression that they indirectly and silently support bullying, which could normalize cyberbullying and increase these behaviors. Although research has been conducted on the factors that determine the likelihood of being bystanders of cyberbullying, parents’ roles in bystanders’ involvement in cyberbullying are unknown.

1.2. Parental Mediation

Parents utilize different parental mediation strategies to manage their children’s relationship with digital technologies (Livingstone and Helsper 2008). One strategy that parents utilize is to set time limits on their children’s digital media use and specifies the type of content that their children views on the internet (Dehue et al. 2008). Oftentimes parents set rules regarding technology use, but do not provide guidelines for appropriate online behavior. Parental mediation strategies involve restrictive, co-viewing, and instructive strategies (Arrizabalaga-Crespo et al. 2010). Restrictive mediation is defined as parents’ use of strategies that prevent their children from accessing specific online content. Co-viewing mediation involves parents and their children accessing online content together. However, parents who co-view content with their children do not always discuss the content with their children. Instructive mediation is defined as parents engaging in active discussion with their children regarding online content.

Parents’ use of mediation strategies has an impact of their children’s behaviors when using digital technologies. Research on parental mediation of technology use and cyberbullying revealed that parental mediation of technology use reduces adolescents’ vulnerability to cyberbullying (Dehue et al. 2008; Livingstone and Helsper 2008; Mesch 2009; Van Den Eijnden et al. 2008). Mesch (2009) found that parental mediation of technology use reduced their children’s risk of experiencing cyberbullying, especially when parents monitored internet use and set rules regarding the websites their children were allowed to visit. Parents’ use of monitoring software and the creation of rules about the amount of time adolescents could interact with digital technologies reduced the likelihood of adolescents sharing personal information online, diminishing adolescents’ cyberbullying involvement (Navarro et al. 2013). Co-viewing mediation and instructive mediation were related negatively to cyberbullying victimization while restrictive mediation was associated positively with cyberbullying perpetration and victimization, as well as cybertrolling (Wright 2016, 2017). It is unclear how parental mediation strategies relate to being bystanders of cyberbullying, and how these strategies might moderate the associations between being bystanders and cyberbullying involvement as bullies and victims. Considering that parental mediation strategies are associated with cyberbullying involvement, it might be likely that similar patterns are found for bystanders of cyberbullying, given that bystanding is also related to cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Vandebosch and Van Cleemput 2009).

1.3. Present Study

Gaps exist in the literature concerning the role of parental mediation of technology use as a moderator in the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and cyberbullying involvement. The aim of the present study was to examine the one-year longitudinal buffering effect of Time 1 (6th or 7th grade) parental mediation of technology use (i.e., restrictive, co-viewing, instructive) in the relationship between Time 1 cyberbullying bystanding and Time 2 (1 year later) cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. We controlled for Time 1 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization, and Time 1 face-to-face bullying perpetration and victimization. The following research questions and hypotheses were examined:

- (1)

- What is the relationship between bystanders of cyberbullying and parental mediation strategies (i.e., restrictive, co-viewing, instructive)?

- Hypothesis 1: We hypothesized that the restrictive mediation strategy will be associated with being bystanders of cyberbullying.

- Hypothesis 2: We hypothesized that instructive and co-viewing mediation strategies will be associated negatively with being bystanders of cyberbullying.

- (2)

- What, if any, moderating effect does parental mediation strategies (i.e., restrictive, co-viewing, instructive) have on the longitudinal associations between cyberbullying involvement (i.e., perpetration, victimization) and bystanders of cyberbullying?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

There were 1067 7th and 8th graders between the ages of 12 and 15 years included in this study. They were recruited from six middle schools in the Midwestern United States from predominantly middle-class neighborhoods. Adolescents self-identified as Caucasian (55.6%), followed by Latino/a (27.8%), Black/African American (8.8%), Asian (7.2%), and Native Hawaiian (0.6%). Family income and educational background for parents/guardians were not collected. Among all students at the six schools, 31% to 53% qualified for free or reduced cost lunch.

2.2. Procedures

Before contacting schools, ethics approval was obtained for this study from the first author’s previous university. A list of 10 middle schools in the Midwestern United States was randomly selected from a list of 165 schools in the area. Recruitment letters were emailed to the principals from the 10 schools. Two principals never replied to the recruitment email, two indicated that they were committed to other research, and six agreed to have their students participate. Meetings were conducted between the researcher, principals, and teachers to introduce them to the study, explain adolescents’ privacy, and what adolescents would do if they participated. Classroom announcements were made to 6th and 7th grade classrooms to inform adolescents about how they could participate, what they would do if they participated, and their rights as participants. There were approximately 1293 parental permission slips sent home with 6th and 7th grade students. There were 103 parental permission slips that were never returned, 79 declining participation, and 1111 parents/guardians agreed to allow their child to participate in the study. Two days were allocated for data collection for all six schools, for a total of 12 days for data collection. On the first day of data collection, 13 students were absent, with 10 of those students participating on the second day of data collection and three never participating in the study. Prior to data collection, adolescents provided their assent, and 11 declined to participate. During the fall of 6th or 7th grade (Time 1; T1), data was collected from 1090 adolescents. They completed questionnaires on cyberbullying bystanding, cyberbullying perpetration, cyberbullying victimization, and parental mediation strategies.

During the fall of 7th or 8th grade (Time 2; T2), a letter was sent home with adolescents reminding their parents/guardians about the study the year prior and informing parents/guardians that their child would be asked to fill out two questionnaires. Parents/guardians were instructed that if they did not want their child to participate again then they should write their child’s first and last name on the letter and then return the letter to their child’s teacher. Two letters were returned to the school. Of the 1090 adolescents from T1, 15 had moved away and eight declined to participate. The final total of adolescents at T2 was 1067. During T2, adolescents completed questionnaires on cyberbullying perpetration and victimization.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Cyberbullying Bystanding

The items on this questionnaire were modified from Wright and Li’s (2013) questionnaire on cyberbullying perpetration and victimization to reflect adolescents witnessing cyberbullying. Adolescents rated six items, using the following scale: 1 (never), 2 (almost never), 3 (sometimes), 4 (almost all the time), and 5 (all the time). Sample items included: Witnessed someone being insulted online and witnessed someone being called mean names online. Items were averaged to form a final score for bystander of cyberbullying. This questionnaire was administered at T1 only. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82.

2.3.2. Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization

Adolescents were asked to indicate how often they experienced and perpetrated cyberbullying (Wright and Li 2013). There were six items for cyberbullying victimization and six items for cyberbullying perpetration; each item was rated on the following scale: 1 (never), 2 (almost never), 3 (sometimes), 4 (almost all the time), and 5 (all the time). For cyberbullying victimization, sample items included: Was insulted online by someone, called mean names online, were the target of gossip online, and had a rumor spread about themselves online. For cyberbullying perpetration, sample items included: Insulted someone online, called someone mean names online, and gossiped about someone online. The items were averaged to form separate scores for cyberbullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration. This questionnaire was administered at T1 and T2. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89 for cyberbullying victimization at both T1 and T2 and 0.88 for cyberbullying perpetration at T1 and 0.87 for T2.

2.3.3. Parental Mediation

This questionnaire asked adolescents how much they agree that their parents are involved in their technology use (Arrizabalaga-Crespo et al. 2010). The questionnaire includes three subscales: Restrictive mediation (4 items; e.g., My parents impose a time limit on the amount of the time that I surf the Internet), co-viewing mediation (3 items; e.g., My parents surf the internet with me), and instructive mediation (2 items; e.g., My parents show me how to use the internet and warn me about its risks). Nine items were rated on a scale of 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The items for each of the subscales were averaged to form measures of restrictive mediation, co-viewing mediation, and instructive mediation. This questionnaire was administered at T1 only. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.89 for restrictive mediation, 0.87 for co-viewing mediation, and 0.83 for instructive mediation.

2.4. Analytic Plan

Means and standard deviations were performed for all the study’s variables. Correlations were conducted between each of the variables as well. A structure regression model was conducted to investigate the study’s purpose. Paths were specified from bystanders of cyberbullying to all three parental mediation strategies (i.e., restrictive, co-viewing, instructive) and T2 cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization, as well as specified from the three parental mediation strategies to T2 cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization. To control for T1 cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization, T1 cyberbullying perpetration was specified to predict T2 cyberbullying perpetration, and T1 cyberbullying victimization was specified to predict T2 cyberbullying victimization. T1 cyberbullying perpetration and cyberbullying victimization were further controlled by having these variables predict bystanders of cyberbullying, T2 cyberbullying perpetration, and T2 cyberbullying victimization. Two-way interactions were also included between bystanders of cyberbullying and the three parental mediation strategies. To probe significant interactions, the Interaction program was used. This program provides the significance of the unstandardized simple regression slopes and displays graphical illustration of the simple slopes at +1 SD, the mean, and −1 SD. Concerning our analyses, the program provided the simple slopes at +1 SD, the mean, and −1 SD for each of the three parental mediation strategies.

3. Results

Means and standard deviations are included in Table 1. Table 1 also includes correlations among the study’s variables. Findings revealed that bystander of cyberbullying was correlated positively with restrictive medication, instructive mediation, and T1 and T2 cyberbullying victimization and perpetration. Parental mediation strategies were unrelated to each other. Restrictive mediation was related positively to T1 and T2 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Instructive mediation was associated negatively with T1 and T2 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Co-viewing mediation was related negatively to T1 and T2 cyberbullying perpetration. T1 and T2 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization were each related to each other.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables.

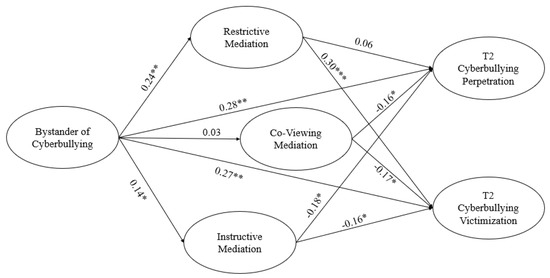

The measurement model was examined using CFA in Mplus 6.12. The model fit was adequate, x2 = 765.03, df = 703, p = n.s., CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04; all standardized factor loadings were significant, ps < 0.001. Items for each questionnaire served as indicators for the latent variables in the structural regression model. The results revealed that the structural model fit the data adequately, x2 = 816.73, df = 789, p = n.s., CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.04 (see Figure 1). Increases in being bystanders of cyberbullying was related positively to restrictive parental mediation (β = 0.24, p < 0.01) and instructive parental mediation (β = 0.14, p < 0.05). Bystanders of cyberbullying was related positively to T2 cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.28, p < 0.01) and T2 cyberbullying victimization (β = 0.27, p < 0.01). Restrictive parental mediation was related positively to T2 cyberbullying victimization (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), while instructive parental mediation was negatively related to T2 cyberbullying perpetration (β = −0.18, p < 0.05) and T2 cyberbullying victimization (β = −0.16, p < 0.05). Restrictive mediation was unrelated to T2 cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.06, p = n.s.). Co-viewing mediation was unrelated to bystander of cyberbullying (β = 0.03, p = n.s.), but it was related negatively to T2 cyberbullying perpetration (β = −0.16, p < 0.05) and T2 cyberbullying victimization (β = −0.17, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the structural regression model. Note: T2 = Time 2. T1 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization were both controlled for by letting both variables predict T2 cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. T1 cyberbullying perpetration was related positively to T2 cyberbullying perpetration (β = 0.20, p < 0.05). T1 cyber victimization was related positively to T2 cyberbullying victimization (β = 0.19, p < 0.05). * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

Restrictive parental mediation was a moderator in the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization. Increases in restrictive parental mediation strengthened the positive relationship between these variables (B = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = 0.01 at the +1 SD; B = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = n.s. at means; B = 0.02, SE = 0.02, p = n.s. at −1 SD). In addition, instructive mediation moderated the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization such that increases in instructive mediation weakened the association between bystanders of cyberbullying and T2 cyberbullying victimization (B = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p = n.s. at the +1 SD; B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p = n.s. at means; B = 0.12, SE = 0.04, p = 0.01 at −1 SD).

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between bystanders of cyberbullying and parental mediation strategies (i.e., instructive, co-viewing, restrictive). Another purpose of this one-year longitudinal study was to examine the moderating effects of parental mediation strategies on the relationship between bystanders of cyberbullying and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization.

Parental mediation of technology use might function as a type of social support. This proposal is possible as parents’ use of mediation strategies affords opportunities to discuss online experiences with their children (Livingstone et al. 2011). These discussions might involve parents discussing strategies with their children on ways to mitigate or reduce exposure to online risks as well as how to deal with these risks (Wright 2015, 2018). Having parents to talk to might help adolescents feel like what happens to them matters, leading them to seek out support and guidance from their parents concerning online experiences (Wright 2018). Adolescents whose parents maintain an open dialogue about online experiences might seek social support from parents when they experience technical problems or uncomfortable situations while using digital technologies (Nikken and de Haan 2015; Talves and Kalmus 2015; Wright 2017). The benefit of parental mediation of technology use is that it encourages continuous communication between parents and their children regarding online experiences.

Bystanders of cyberbullying was related positively to restrictive mediation, providing support for Hypothesis 1. Instructive mediation was also positively associated with bystanders of cyberbullying, and co-viewing mediation was unrelated to bystanders of cyberbullying. These findings fail to support Hypothesis 2, as both parental mediation strategies were expected to relate negatively to witnessing cyberbullying. These findings suggest that adolescents might witness cyberbullying regardless of whether they believe their parent utilizes restrictive mediation or instructive mediation. Given that 30% to 60% of adolescents witness cyberbullying, it might be likely that this is a common experience for adolescents, unrelated to their parents’ use of restrictive mediation or instructive mediation (Huang and Chou 2010; Van Cleemput et al. 2014; Vandebosch and Van Cleemput 2009). Consequently, our findings suggest that the association between restrictive and instructive parental mediation strategies and witnessing cyberbullying do not follow similar patterns as those found in previous studies linking parental mediation strategies to cyberbullying perpetration and victimization (Vandebosch and Van Cleemput 2009; Wright 2018).

We found that increases in restrictive parental mediation strengthened the positive relationship between bystanders of cyberbullying and Time 2 cyberbullying victimization. The finding regarding restrictive mediation is consistent with the literature (Wright 2015). Restrictive mediation involves elements of an overprotective parenting style in which children do not have opportunities to develop problem-solving skills and social skills (Clarke et al. 2013; Lereya et al. 2013). The use of restrictive mediation does not allow adolescents to develop strategies for dealing with online risks, which might increase their exposure to risk situations, such as cyberbullying (Smahel and Wright 2014). Because these adolescents do not learn problem-solving skills, they might be unable to avoid situations that might increase their likelihood of experiencing cyberbullying victimization.

The relationships between bystanders and Time 2 cyberbullying victimization were weakened at higher levels of the instructive mediation strategy. These findings are consistent with the literature, suggesting that this form of parental mediation reduces the risk of cyberbullying victimization (Mesch 2009; Navarro et al. 2013; Wright 2015). Through the use of instructive parental mediation, parents are able to provide social support through ongoing discussions with their children, which provides opportunities for adolescents to learn about strategies for avoiding cyberbullying involvement (Mesch 2009; Nikken and de Haan 2015; Talves and Kalmus 2015). Such discussion might involve teaching adolescents about technical and social support coping strategies that reduce adolescents’ exposure to cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. These adolescents might also avoid situations that could lead to being involved in cyberbullying.

Co-viewing mediation did not moderate the associations between bystanders of cyberbullying and cyberbullying perpetration or victimization. Although parents who utilize co-viewing strategies might not necessarily discuss content with their children, there might be some minimal amount of discussion on appropriate content and ways to deal with negative online situations (Arrizabalaga-Crespo et al. 2010). Wright (2015) found that co-viewing parental mediation was negatively associated with cyberbullying victimization. More research attention should be given to the nuances of the different parental mediation strategies, particularly the co-viewing strategy, to understand the mechanisms behind these strategies and how they mitigate online risks.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study contributes valuable knowledge to the literature on the buffering effects of the instructive parental mediation strategy on the associations between bystanders of cyberbullying and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration, as well as how restrictive mediation increases these associations. There are a few limitations of this research that needs to be acknowledged. The first limitation is that the study relied on self-reports for all variables, making the findings susceptible to self-report biases. It is important for follow-up research to implement multiple informants, such as assessing parents’ own perceptions of mediation strategies. Including peer-reports might also be helpful for providing more objective assessments of cyberbullying involvement. Such a methodological improvement might reduce the biases associated with self-reports. It is also important for researchers to further investigate the characteristics of the three parental mediational strategies utilized in this study. This follow-up research will make it possible to better understand the unique associations of the parental mediation strategies to the different roles adolescents can have in cyberbullying involvement. Another limitation is that parental mediation strategies and bystanders of cyberbullying were assessed at one time point only. Future research should investigate these variables at additional time points as well. This improvement will make it possible to determine the temporal ordering of the variables and the moderation effects examined in this study. Despite the large sample size included in this study, the sample cannot be considered representative, given that a small number of schools were recruited. Consequently, it is important for researchers to conduct studies with representatives to increase the generalizability of this research. It is also necessary for researchers to include diverse samples.

5. Conclusions

An important finding from this study is that adolescents are at risk for witnessing cyberbullying, regardless of whether they believe their parents utilize restrictive mediation or instructive mediation. Parental mediation strategies have important implications on bystanders’ involvement in cyberbullying one year later. Therefore, the current findings indicate a need for parents to be aware of how they can impact their children’s involvement in cyberbullying as victims and bullies.

Greater attention should be given to developing parental intervention programs that focus on the role of parents in helping to mitigate their children’s likelihood of cyberbullying involvement. Parents might also be important for helping adolescents develop effective coping strategies for witnessing bullying; such coping strategies might empower adolescents to actually use these strategies to help the victim. Being able to cope with the unpleasant feelings associated with witnessing cyberbullying and helping the victim might help bystanders overcome the potential of engaging in cyberbullying and reduce their risk of cyberbullying victimization. Empowering bystanders to intervene might help to reduce negative feelings that could trigger cyberbullying perpetration. Parents/guardians should be educated on how they can support adolescents who report witnessing cyberbullying. Awareness among parents/guardians regarding the impact of witnessing cyberbullying might be possible through the use of social media advertisements designed to spread knowledge about cyberbullying and the role they have in reducing adolescents’ risk.

Author Contributions

M.F.W. was the Principal Investigator, designed, and conducted this study. She performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. S.W. provided constructive feedback on drafts of the manuscript. M.F.W. processed feedback from the author, reviewers, and editor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the adolescents who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arrizabalaga-Crespo, C., A. Aierbe-Barandiaran, and C. Medrano-Samaniego. 2010. Internet uses and parental mediation in adolescents with ADHD. Revista Latina de Comunicación 65: 561–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K., P. Cooper, and C. Creswell. 2013. The Parental Overprotection Scale: Associations with child and parental anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 151: 618–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehue, F., C. Bolman, and T. Völlink. 2008. Cyberbullying: Youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 11: 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdon, C. D., and M. F. Hertz. 2007. Electronic media, violence, and adolescents: An emerging public health problem. Journal of Adolescent Health 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, D. W. 2010. Cyber-aggression: Definition and concept of cyberbullying. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 20: 143–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S., and J. W. Patchin. 2008. Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behavior 29: 129–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., and C. Chou. 2010. An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior 26: 1581–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., and S. P. Limber. 2007. Electronic bullying among middle school students. Journal of Adolescent Health 41: S22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lereya, S. T., M. Samara, and D. Wolke. 2013. Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse and Neglect 37: 1091–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, S., and E. J. Helsper. 2008. Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 52: 581–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., L. Haddon, A. Görzig, and K. Ólafsson. 2011. Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children. London: EU Kids Online, London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Mesch, G. S. 2009. Parental mediation, online activities, and cyberbullying. CyberPsychology & Behavior 12: 387–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R., C. Serna, V. Martínez, and R. Ruiz-Oliva. 2013. The role of internet use and parental mediation on cyberbullying victimization among Spanish children from rural public schools. European Journal of Psychology of Education 28: 725–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikken, P., and J. de Haan. 2015. Guiding young children’s internet use at home: Problems that parents experience in their parental mediation and the need for parenting support. Cyberpsychology. Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, I., V. P. Poteat, N. Noret, and N. Ashurst. 2009. Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly 24: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, H., and G. Mesch. 2017. The role of parental mediation and peer norms on the likelihood of cyberbullying. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development 178: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smahel, D., and M. F. Wright. 2014. The Meaning of Online Problematic Situations for Children: Results of Qualitative Cross-Cultural Investigation in Nine European Countries. London: EU Kids Online, London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. K., J. Mahdavi, M. Carvalho, S. Fisher, S. Russell, and N. Tippett. 2008. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49: 376–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suler, J. 2004. The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior 7: 321–26. [Google Scholar]

- Talves, K., and V. Kalmus. 2015. Gendered mediation of children’s internet use: A keyhole for looking into changing socialization practices. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, C., O. Erdur-Baker, and Y. Capa-Aydin. 2008. Examination of cyber-bullying experiences among Turkish students from different school types. CyberPsychology & Behavior 11: 644–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udris, R. 2014. Cyberbullying among high school students in Japan: Development and validation of the Online Disinhibition Scale. Computers in Human Behavior 41: 253–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleemput, K., H. Vandebosch, and S. Pabian. 2014. Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “Helping,” “Joining In,” and “Doing Nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior 40: 383–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Eijnden, R., G. Meerkerk, A. Vermulst, R. Spijkerman, and R. C. M. E. Engels. 2008. Online communication, compulsive internet use, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology 44: 655–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandebosch, H., and K. Van Cleemput. 2009. Cyberbullying among youngsters: Profiles of bullies and victims. New Media & Society 11: 1349–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wachs, S. 2012. Moral disengagement and emotional and social difficulties in bullying and cyberbullying: Differences by participant role. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 17: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs, S., M. Junger, and R. Sittichai. 2015. Traditional, cyber and combined bullying roles: Differences in risky online and offline activities. Societies 5: 109–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C., B. Sockman, and S. Koehn. 2011. An exploratory study of cyberbullying with undergraduate university students. Tech Trends 55: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolak, J., K. Mitchell, and D. Finkelhor. 2007. Does online harassment constitute bullying? An exploration of online harassment by known peers and online-only Cybervictimization and Substance Use among Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M. F. 2014. Predictors of anonymous cyber aggression: The role of adolescents’ beliefs about anonymity, aggression, and the permanency of digital content. CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17: 431–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M. F. 2015. Cyber victimization and adjustment difficulties: The mediation of Chinese and American adolescents’ digital technology usage. CyberPsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research in Cyberspace 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. 2016. Cybervictimization and substance use among adolescents: The moderation of perceived social support. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 16: 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. 2017. Parental mediation, cyberbullying, and cybertrolling: The role of gender. Computers in Human Behavior 71: 189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. 2018. Cyberbullying Victimization through Social Networking Sites and Adjustment Difficulties: The Role of Parental Mediation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 19. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol19/iss2/1 (accessed on 10 September 2018). [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F., and Y. Li. 2013. The association between cyber victimization and subsequent cyber aggression: The moderating effect of peer rejection. Journal of Youth & Adolescence 42: 662–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M. L., M. Diener-West, and P. J. Leaf. 2007. Examining the overlap in internet harassment and school bullying: Implications for school intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).